Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Strelbytskyy Multimedia Publishing

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Rabindhranath Tagore reshaped Bengali literature and music as well as Indian art with Contextual Modernism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Author of the "profoundly sensitive, fresh and beautiful" poetry of Gitanjali, he became in 1913 the first non-European and the first lyricist to win the Nobel Prize in Literature. Referred to as "the Bard of Bengal", Tagore was known by sobriquets: Gurudev, Kobiguru, Biswakobi. Tagore's poetic songs were viewed as spiritual and mercurial; however, his "elegant prose and magical poetry" remain largely unknown outside Bengal. Poetry 1. Ama and Vinayaka 2. Baul Songs 3. Collected Poems 3.1. Boro-Budur 3.2. The Child 3.3. Freedom 3.4. From Hindi Songs of Jnanadas 3.5. Fulfilment 3.6. Krishnakali 3.7. The New Year 3.8. Raidas, the Sweeper 3.9. Santiniketan Song 3.10. Shesher Kobita 3.11. The Son of Man 3.12. This Evil Day 3.13. W.W. Pearson 4. Fruit-Gathering 5. The Fugitive 6. Gitanjali 7. Kacha and Devayani 8. Karna and Kunti 9. Lover's Gift 10. The Mother's Prayer 11. Other Poems 12. Somaka and Ritvik 13. Songs of Kabir 14. Stray Birds 15. Vaishnava Songs Short Stories 1. A Feast for Rats 2. The Auspicious Vision 3. The Babus of Nayanjore 4. The Cabuliwallah 5. The Castaway 6. The Child's Return 7. The Devotee 8. The Editor 9. The Elder Sister 10. Emancipation 11. Exercise-book 12. Finally 13. The Fugitive Gold 14. The Gift of Vision 15. Giribala 16. Haimanti: Of Autumn 17. Holiday 18. The Home-Coming 19. The Hungry Stones 20. In the Night 21. The Kingdom of Cards 22. Living or Dead? 23. The Lost Jewels 24. Mashi 25. Master Mashai 26. My Fair Neighbour 27. My Lord, the Baby 28. Once there was a King 29. The Parrot's Training 30. The Patriot 31. The Postmaster 32. Raja and Rani 33. The Renunciation 34. The Riddle Solved 35. The River Stairs 36. Saved 37. The Skeleton 38. The Son of Rashmani 39. Subha 40. The Supreme Night 41. Unwanted 42. The Victory 43. Vision 44. We Crown Thee King Novels 1. The Broken Ties (Nastanirh) 2. The Home and the World 3. The Religion of Man Plays 1. Autumn-Festival 2. Chitra 3. The Cycle of Spring 4. The Gardener 5. The King and the Queen 6. The King of the Dark Chamber 7. Malini 8. The Post Office 9. Red Oleanders 10. Sacrifice 11. Sanyasi or the Ascetic 12. The Trial 13. The Waterfall Essays 1. The Center of Indian Culture 2. Creative Unity 2.1. An Eastern University 2.2. An Indian Folk Religion 2.3. The Creative Ideal 2.4. East and West 2.5. The Modern Age 2.6. The Nation 2.7. The Poet's Religion 2.8. The Religion of the Forest 2.9. The Spirit of Freedom 2.10. Woman and Home 3. Nationalism 3.1. Nationalism in India 3.2. Nationalism in Japan 3.3. Nationalism in the West 3.4. The Sunset of the Century 4. Sadhana 4.1. The Problem of Evil 4.2. The Problem of Self 4.3. Realization in Action 4.4. Realization in Love 4.5. The Realization of Beauty 4.6. The Realization of the Infinite 4.7. The Relation of the Individual to the Universe 4.8. Soul Consciousness 5. The Spirit of Japan Non-Fiction 1. Glimpses of Bengal Introduction 1885 1887 1888 1890 1891 1892 1893 1894 1895 2. My Reminiscences Part 1 - Part 8

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 3505

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

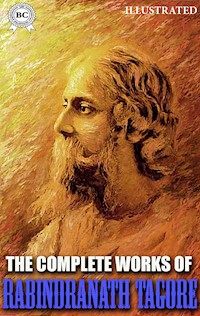

Rabindranath Tagore

The Complete Works of Rabindranath Tagore

Illustrated

Rabindhranath Tagore reshaped Bengali literature and music as well as Indian art with Contextual Modernism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Author of the "profoundly sensitive, fresh and beautiful" poetry of Gitanjali, he became in 1913 the first non-European and the first lyricist to win the Nobel Prize in Literature.

Referred to as "the Bard of Bengal", Tagore was known by sobriquets: Gurudev, Kobiguru, Biswakobi.

Tagore's poetic songs were viewed as spiritual and mercurial; however, his "elegant prose and magical poetry" remain largely unknown outside Bengal.

Poetry

1. Ama and Vinayaka

2. Baul Songs

3. Collected Poems

3.1. Boro-Budur

3.2. The Child

3.3. Freedom

3.4. From Hindi Songs of Jnanadas

3.5. Fulfilment

3.6. Krishnakali

3.7. The New Year

3.8. Raidas, the Sweeper

3.9. Santiniketan Song

3.10. Shesher Kobita

3.11. The Son of Man

3.12. This Evil Day

3.13. W.W. Pearson

4. Fruit-Gathering

5. The Fugitive

The Fugitive I

The Fugitive II

The Fugitive III

6. Gitanjali

7. Kacha and Devayani

8. Karna and Kunti

9. Lover’s Gift

10. The Mother’s Prayer

11. Other Poems

12. Somaka and Ritvik

13. Songs of Kabir

14. Stray Birds

15. Vaishnava Songs

Short Stories

1. A Feast for Rats

2. The Auspicious Vision

3. The Babus of Nayanjore

4. The Cabuliwallah

5. The Castaway

6. The Child’s Return

7. The Devotee

8. The Editor

9. The Elder Sister

10. Emancipation

11. Exercise-book

12. Finally

13. The Fugitive Gold

14. The Gift of Vision

15. Giribala

16. Haimanti: Of Autumn

17. Holiday

18. The Home-Coming

19. The Hungry Stones

20. In the Night

21. The Kingdom of Cards

22. Living or Dead?

23. The Lost Jewels

24. Mashi

25. Master Mashai

26. My Fair Neighbour

27. My Lord, the Baby

28. Once there was a King

29. The Parrot’s Training

30. The Patriot

31. The Postmaster

32. Raja and Rani

33. The Renunciation

34. The Riddle Solved

35. The River Stairs

36. Saved

37. The Skeleton

38. The Son of Rashmani

39. Subha

40. The Supreme Night

41. Unwanted

42. The Victory

43. Vision

44. We Crown Thee King

Novels

1. The Broken Ties (Nastanirh)

2. The Home and the World

3. The Religion of Man

Plays

1. Autumn-Festival

2. Chitra

3. The Cycle of Spring

4. The Gardener

5. The King and the Queen

6. The King of the Dark Chamber

7. Malini

8. The Post Office

9. Red Oleanders

10. Sacrifice

11. Sanyasi or the Ascetic

12. The Trial

13. The Waterfall

Essays

1. The Center of Indian Culture

2. Creative Unity

2.1. An Eastern University

2.2. An Indian Folk Religion

2.3. The Creative Ideal

2.4. East and West

2.5. The Modern Age

2.6. The Nation

2.7. The Poet’s Religion

2.8. The Religion of the Forest

2.9. The Spirit of Freedom

2.10. Woman and Home

3. Nationalism

3.1. Nationalism in India

3.2. Nationalism in Japan

3.3. Nationalism in the West

3.4. The Sunset of the Century

4. Sadhana

4.1. The Problem of Evil

4.2. The Problem of Self

4.3. Realization in Action

4.4. Realization in Love

4.5. The Realization of Beauty

4.6. The Realization of the Infinite

4.7. The Relation of the Individual to the Universe

4.8. Soul Consciousness

5. The Spirit of Japan

Non-Fiction

1. Glimpses of Bengal

Introduction

1885

1887

1888

1890

1891

1892

1893

1894

1895

2. My Reminiscences

Part 1

1. My Reminiscences

2. Teaching Begins

3. Within and Without

Part 2

4. Servocracy

5. The Normal School

6. Versification

7. Various Learning

8. My First Outing

9. Practising Poetry

Part 3

10. Srikantha Babu

11. Our Bengali Course Ends

12. The Professor

13. My Father

14. A journey with my Father

15. At the Himalayas

Part 4

16. My Return

17. Home Studies

18. My Home Environment

19. Literary Companions

20. Publishing

21. Bhanu Singha

22. Patriotism

23. The Bharati

Part 5

24. Ahmedabad

25. England

26. Loken Palit

27. The Broken Heart

Part 6

28. European Music

29. Valmiki Pratibha

30. Evening Songs

31. An Essay on Music

32. The River-side

33. More about the Evening Songs

34. Morning Songs

Part 7

35. Rajendrahal Mitra

36. Karwar

37. Nature’s Revenge

38. Pictures and Songs

39. An Intervening Period

40. Bankim Chandra

Part 8

41. The Steamer Hulk

42. Bereavements

43. The Rains and Autumn

44. Sharps and Flats

Poetry

1. Ama and Vinayaka

Night on the battlefield: AMA meets her father VINAYAKA.

AMA : Father!

VINAYAKA : Shameless wanton, you call me “Father”! You who did not shrink from a Mussulman husband!

AMA : Though you have treacherously killed my husband, yet you are my father; and I hold back a widow’s tears, lest they bring God’s curse on you. Since we have met on this battlefield after years of separation, let me bow to your feet and take my last leave!

VINAYAKA : Where will you go, Ama? The tree on which you built your impious nest is hewn down. Where will you take shelter?

AMA : I have my son.

VINAYAKA : Leave him! Cast never a fond look back on the result of a sin expiated with blood! Think where to go.

AMA : Death’s open gates are wider than a father’s love!

VINAYAKA : Death indeed swallows sins as the sea swallows the mud of rivers. But you are to die neither to-night nor here. Seek some solitary shrine of holy Shiva far from shamed kindred and all neighbours; bathe three times a day in sacred Ganges, and, while reciting God’s name, listen to the last bell of evening worship, that Death may look tenderly upon you, as a father on his sleeping child whose eyes are still wet with tears. Let him gently carry you into his own great silence, as the Ganges carries a fallen flower on its stream, washing every stain away to render it, a fit offering, to the sea.

AMA : But my son——

VINAYAKA : Again I bid you not to speak of him. Lay yourself once more in a father’s arms, my child, like a babe fresh from the womb of Oblivion, your second mother.

AMA : To me the world has become a shadow. Your words I hear, but cannot take to heart. Leave me, father, leave me alone! Do not try to bind me with your love, for its bands are red with my husband’s blood.

VINAYAKA : Alas! No flower ever returns to the parent branch it dropped from. How can you call him husband who forcibly snatched you from Jivaji to whom you had been sacredly affianced? I shall never forget that night! In the wedding hall we sat anxiously expecting the bridegroom, for the auspicious hour was dwindling away. Then in the distance appeared the glare of torches, and bridal strains came floating up the air. We shouted for joy: women blew their conch-shells. A procession of palanquins entered the courtyard: but while we were asking, “Where is Jivaji?” armed men burst out of the litters like a storm, and bore you off before we knew what had happened. Shortly after, Jivaji came to tell us he had been waylaid and captured by a Mussulman noble of the Vijapur court. That night Jivaji and I touched the nuptial fire and swore bloody death to this villain. After waiting long, we have been freed from our solemn pledge to-night; and the spirit of Jivaji, who lost his life in this battle, lawfully claims you for wife.

AMA : Father, it may be that I have disgraced the rites of your house, but my honour is unsullied; I loved him to whom I bore a son. I remember the night when I received two secret messages, one from you, one from my mother; yours said: “I send you the knife; kill him!” My mother’s: “I send you the poison; end your life!” Had unholy force dishonoured me, your double bidding had been obeyed. But my body was yielded only after love had given me—love all the greater, all the purer, in that it overcame the hereditary recoil of our blood from the Mussulman.

Enter RAMA, Ama’s mother.

AMA : Mother mine, I had not hoped to see you again. Let me take dust from your feet.

RAMA : Touch me not with impure hands!

AMA : I am as pure as yourself.

RAMA : To whom have you surrendered your honour?

AMA : To my husband.

RAMA : Husband? A Mussulman the husband of a Brahmin woman?

AMA : I do not merit contempt: I am proud to say I never despised my husband though a Mussulman. If Paradise will reward your devotion to your husband, then the same Paradise waits for your daughter, who has been as true a wife.

RAMA : Are you indeed a true wife?

AMA : Yes.

RAMA : Do you know how to die without flinching?

AMA : I do.

RAMA : Then let the funeral fire be lighted for you! See, there lies the body of your husband.

AMA : Jivaji?

RAMA : Yes, Jivaji. He was your husband by plighted troth. The baffled fire of the nuptial God has raged into the hungry fire of death, and the interrupted wedding shall be completed now.

VINAYAKA : Do not listen, my child. Go back to your son, to your own nest darkened with sorrow. My duty has been performed to its extreme cruel end, and nothing now remains for you to do.—Wife, your grief is fruitless. Were the branch dead which was violently snapped from our tree, I should give it to the fire. But it has sent living roots into a new soil and is bearing flowers and fruits. Allow her, without regret, to obey the laws of those among whom she has loved. Come, wife, it is time we cut all worldly ties and spent our remainder lives in the seclusion of some peaceful pilgrim shrine.

RAMA : I am ready: but first must tread into dust every sprout of sin and shame that has sprung from the soil of our life. A daughter’s infamy stains her mother’s honour. That black shame shall feed glowing fire to-night, and raise a true wife’s memorial over the ashes of my daughter.

AMA : Mother, if by force you unite me in death with one who was not my husband, then will you bring a curse upon yourself for desecrating the shrine of the Eternal Lord of Death.

RAMA : Soldiers, light the fire; surround the woman!

AMA : Father!

VINAYAKA : Do not fear. Alas, my child, that you should ever have to call your father to save you from your mother’s hands!

AMA : Father!

VINAYAKA : Come to me, my darling child! Mere vanity are these man-made laws, splashing like spray against the rock of heaven’s ordinance. Bring your son to me, and we will live together, my daughter. A father’s love, like God’s rain, does not judge but is poured forth from an abounding source.

RAMA : Where would you go? Turn back!—Soldiers, stand firm in your loyalty to your master Jivaji! Do your last sacred duty by him!

AMA : Father!

VINAYAKA : Free her, soldiers! She is my daughter.

SOLDIERS : She is the widow of our master.

VINAYAKA : Her husband, though a Mussulman, was staunch in his own faith.

RAMA : Soldiers, keep this old man under control!

AMA : I defy you, mother!—You, soldiers, I defy!—for through death and love I win to freedom.

* * *

A painter was selling pictures at the fair; followed by servants, there passed the son of a minister who in youth had cheated this painter’s father so that he had died of a broken heart.

The boy lingered before the pictures and chose one for himself. The painter flung a cloth over it and said he would not sell it.

After this the boy pined heart-sick till his father came and offered a large price. But the painter kept the picture unsold on his shop-wall and grimly sat before it, saying to himself, “This is my revenge.”

The sole form this painter’s worship took was to trace an image of his god every morning.

And now he felt these pictures grow daily more different from those he used to paint.

This troubled him, and he sought in vain for an explanation till one day he started up from work in horror, the eyes of the god he had just drawn were those of the minister, and so were the lips.

He tore up the picture, crying, “My revenge has returned on my head!”

* * *

The General came before the silent and angry King and saluting him said: “The village is punished, the men are stricken to dust, and the women cower in their unlit homes afraid to weep aloud.”

The High Priest stood up and blessed the King and cried: “God’s mercy is ever upon you.”

The Clown, when he heard this, burst out laughing and startled the court. The King’s frown darkened.

“The honour of the throne,” said the minister, “is upheld by the King’s prowess and the blessing of Almighty God.”

Louder laughed the Clown, and the King growled,—“Unseemly mirth!”

“God has showered many blessings upon your head,” said the Clown; “the one he bestowed on me was the gift of laughter.”

“This gift will cost you your life,” said the King, gripping his sword with his right hand.

Yet the Clown stood up and laughed till he laughed no more.

A shadow of dread fell upon the Court, for they heard that laughter echoing in the depth of God’s silence.

2. Baul Songs[1]

1

This longing to meet in the play of love, my Lover, is not only mine but yours.

Your lips can smile, your flute make music, only through delight in my love; therefore you are importunate even as I.

2

I sit here on the road; do not ask me to walk further.

If your love can be complete without mine let me turn back from seeking you.

I refuse to beg a sight of you if you do not feel my need.

I am blind with market dust and mid-day glare, and so wait, in hopes that your heart, my heart’s lover, will send you to find me.

3

I am poured forth in living notes of joy and sorrow by your breath.

Mornings and evenings in summer and in rains, I am fashioned to music.

Should I be wholly spent in some flight of song, I shall not grieve, the tune is so dear to me.

4

My heart is a flute he has played on. If ever it fall into other hands let him fling it away.

My lover’s flute is dear to him, therefore if to-day alien breath have entered it and sounded strange notes, let him break it to pieces and strew the dust with them.

5

In love the aim is neither pain nor pleasure but love only.

While free love binds, division destroys it, for love is what unites.

Love is lit from love as fire from fire, but whence came the first flame?

In your being it leaps under the rod of pain.

Then, when the hidden fire flames forth, the in and the out are one and all barriers fall in ashes.

Let the pain glow fiercely, burst from the heart and beat back darkness, need you be afraid?

The poet says, “Who can buy love without paying its price? When you fail to give yourself you make the whole world miserly.”

6

Eyes see only dust and earth, but feel with the heart, and know pure joy.

The delights blossom on all sides in every form, but where is your heart’s thread to make a wreath of them?

My master’s flute sounds through all things, drawing me out of my lodgings wherever they may be, and while I listen I know that every step I take is in my master’s house.

For he is the sea, he is the river that leads to the sea, and he is the landing-place.

7

Strange ways has my guest.

He comes at times when I am unprepared, yet how can I refuse him?

I watch all night with lighted lamp; he stays away; when the light goes out and the room is bare he comes claiming his seat, and can I keep him waiting?

I laugh and make merry with friends, then suddenly I start up, for lo! He passes me by in sorrow, and I know my mirth was vain.

I have often seen a smile in his eyes when my heart ached, then I knew my sorrow was not real.

Yet I never complain when I do not understand him.

8

I am the boat, you are the sea, and also the boatman.

Though you never make the shore, though you let me sink, why should I be foolish and afraid?

Is reaching the shore a greater prize than losing myself with you?

If you are only the haven, as they say, then what is the sea?

Let it surge and toss me on its waves, I shall be content.

I live in you whatever and however you appear. Save me or kill me as you wish, only never leave me in other hands.

9

Make way, O bud, make way, burst open thy heart and make way.

The opening spirit has overtaken thee, canst thou remain a bud any longer?

3. Collected Poems

3.1. Boro-Budur

The sun shone on a far-away morning, while the forest murmured its hymn of praise to light; and the hills, veiled in vapour, dimly glimmered like earth’s dream in purple.

The King sat alone in the coconut grove, his eyes drowned in a vision, his heart exultant with the rapturous hope of spreading the chant of adoration along the unending path of time:

‘Let Buddha be my refuge.’

His words found utterance in a deathless speech of delight, in an ecstasy of forms.

The island took it upon her heart; her hill raised it to the sky.

Age after age, the morning sun daily illumined its great meaning.

While the harvest was sown and reaped in the near-by fields by the stream, and life, with its chequered light, made pictured shadows on its epochs of changing screen, the prayer, once Uttered in the quiet green of an ancient morning, ever rose in the midst of the hide-and-seek of tumultuous time:

‘Let Buddha be my refuge.’

The King, at the end of his days, is merged in the shadow of a nameless night among the unremembered, leaving his salutation in an imperishable rhythm of stone which ever cries:

‘Let Buddha be my refuge.’

Generations of pilgrims came on the quest of an immortal voice for their worship; and this sculptured hymn, in a grand symphony of gestures, took up their lowly names and uttered for them:

‘Let Buddha be my refuge.’

The spirit of those words has been muffled in mist in this mocking age of unbelief, and the curious crowds gather here to gloat in the gluttony of an irreverent sight.

Man to-day has no peace, his heart arid with pride. He clamours for an ever-increasing speed in a fury of chase for objects that ceaselessly run, but never reach a meaning.

And now is the time when he must come groping at last to the sacred silence, which stands still in the midst of surging centuries of noise, till he feels assured that in an immeasurable love dwells the final meaning of Freedom, whose prayer is:

‘Let Buddha be my refuge.’

3.2. The Child

1

‘What of the night?’ they ask.

No answer comes.

For the blind Time gropes in a maze and knows not its path or purpose.

The darkness in the valley stares like the dead eye-sockets of a giant, the clouds like a nightmare oppress the sky, and the massive shadows lie scattered like the torn limbs of the night.

A lurid glow waxes and wanes on the horizon, is it an ultimate threat from an alien-star, or an elemental hunger licking the sky?

Things are deliriously wild, they are a noise whose grammar is a groan, and words smothered out of shape and sense.

They are the refuse, the rejections, the fruitless failures of life, abrupt ruins of prodigal pride, fragments of a bridge over the oblivion Of a vanished stream, godless shrines that shelter reptiles, marble steps that lead to blankness.

Sudden tumults rise in the sky and wrestle and a startled shudder runs along the sleepless hours.

Are they from desperate floods hammering against their cave walls, or from some fanatic storms whirling and howling incantations?

Are they the cry of an ancient forest flinging up its hoarded fire in a last extravagant suicide, or screams of a paralytic crowd scourged by lunatics blind and deaf?

Underneath the noisy terror a stealthy hum creeps up like bubbling volcanic mud, a mixture of sinister whispers, rumours and slanders, and hisses of derision.

The men gathered there are vague like torn pages of an epic.

Groping in groups or single, their torchlight tattoos their faces in chequered lines, in patterns of frightfulness.

The maniacs suddenly strike their neighbours on suspicion and a hubbub of an indiscriminate fight bursts forth echoing from hill to hill.

The women weep and wail, they cry that their children are lost in a wilderness of contrary paths with confusion at the end.

Others defiantly ribald shake with raucous laughter their lascivious limbs unshrinkingly loud, for they think that nothing matters.

2

There on the crest of the hill stands the Man of faith amid the snow-white silence,

He scans the sky for some signal of light, and when the clouds thicken and the night birds scream as they fly he cries, ‘Brothers, despair not, for Man is great.’

But they never heed him, for they believe that the elemental brute is eternal and goodness in its depth is darkly cunning in deception.

When beaten and wounded they cry, ‘Brother, where art thou?’

The answer comes, ‘I am by your side.’

But they cannot see in the dark and they argue that the voice is of their own desperate desire, that men are ever condemned to fight for phantoms in an interminable desert of mutual menace.

3

The clouds part, the morning star appears in the East, a breath of relief springs up from the heart of the earth, the murmur of leaves ripples along the forest path, and the early bird sings.

‘The time has come,’ proclaims the Man of faith.

‘The time for what?’

‘For the pilgrimage.’

They sit and think, they know not the meaning, and yet they seem to understand according to their desires.

The touch of the dawn goes deep into the soil and life shivers along through the roots of all things.

‘To the pilgrimage of fulfilment,’ a small voice whispers, nobody knows whence.

Taken up by the crowd it swells into a mighty meaning.

Men raise their heads and look up, women lift their arms in reverence, children clap their hands and laugh.

The early glow of the sun shines like a golden garland on the forehead of the Man of faith, and they all cry: ‘Brother, we salute thee!’

4

Men begin to gather from all quarters, from across the, seas, the mountains and pathless wastes,

They come from the valley of the Nile and the banks of the Ganges, from the snow-sunk uplands of Thibet, from high-walled cities of glittering towers, from the dense dark—tangle of savage wilderness.

Some walk, some ride on camels, horses and elephants, on chariots with banners vieing with the clouds of dawn,

The priests of all creeds burn incense, chanting verses as they go.

The monarchs march at the head of their armies, lances flashing in the sun and drums beating loud.

Ragged beggars and courtiers pompously decorated, agile young scholars and teachers burdened with learned age jostle each other in the crowd.

Women come chatting and laughing, mothers, maidens and brides, with offerings of flowers and fruit, sandal paste and scented water.

Mingled with them is the harlot, shrill of voice and loud in tint and tinsel.

The gossip is there who secretly poisons the well of human sympathy and chuckles.

The maimed and the cripple join the throng with the blind and the sick, the dissolute, the thief and the man who makes a trade of his God for profit and mimics the saint.

‘The fulfilment!’

They dare not talk aloud, but in their minds they magnify their own greed, and dream of boundless power, of unlimited impunity for pilfering and plunder, and eternity of feast for their unclean gluttonous flesh.

5

The man of faith moves on along pitiless paths strewn with flints over scorching sands and steep mountainous tracks.

They follow him, the strong and the weak, the aged and young, the rulers of realms, the tillers of the soil.

Some grow weary and footsore, some angry and suspicious.

They ask at every dragging step,

‘How much further is the end?’

The Man of faith sings in answer; they scowl and shake their fists and yet they cannot resist him; the pressure of the moving mass and indefinite hope push them forward.

They shorten their sleep and curtail their rest, they out-vie each other in their speed, they are ever afraid lest they may be too late for their chance while others be more fortunate.

The days pass, the ever-receding horizon tempts them with renewed lure of the unseen till they are sick.

Their faces harden, their curses grow louder and louder.

6

It is night.

The travellers spread their mats on the ground under the banyan tree.

A gust of wind blows out the lamp and the darkness deepens like a sleep into a swoon.

Someone from the crowd suddenly stands up and pointing to the leader with merciless finger breaks out:

‘False prophet, thou hast deceived us!’

Others take up the cry one by one, women hiss their hatred and men growl.

At last one bolder than others suddenly deals him a blow.

They cannot see his face, but fall upon him in a fury of destruction and hit him till he lies prone upon the ground his life extinct.

The night is still, the sound of the distant waterfall comes muffled and a faint breath of jasmine floats in the air.

7

The pilgrims are afraid.

The woman begins to cry, the men in an agony of wretchedness shout at them to stop.

Dogs break out barking and are cruelly whipped into silence broken by moans.

The night seems endless and men and women begin to wrangle as to who among them was to blame.

They shriek and shout and as they are ready to unsheathe their knives the darkness pales, the morning light overflows the mountain tops.

Suddenly they become still and gasp for breath as they gaze at the figure lying dead.

The women sob out loud and men hide their faces in their hands.

A few try to slink away unnoticed, but their crime keeps them chained to their victim.

They ask each other in bewilderment,

‘Who will show us the path?’

The old man from the East bends his head and says:

‘The Victim.’

They sit still and silent.

Again speaks the old man,

‘We refused him in doubt, we killed him in anger, now we shall accept him in love, for in his death he lives in the life of us all, the great Victim.’

And they all stand up and mingle their voices and sing,

‘Victory to the Victim.’

8

‘To the pilgrimage’ calls the young, ‘to love, to power, to knowledge, to wealth overflowing,’

‘We shall conquer the world and the world beyond this,’ they all cry exultant in a thundering cataract of voices,

The meaning is not the same to them all, but only the impulse, the moving confluence of wills that recks not death and disaster.

No longer they ask for their way, no more doubts are there to burden their minds or weariness to clog their feet.

The spirit of the Leader is within them and ever beyond them the Leader who has crossed death and all limits.

They travel over the fields where the seeds are sown, by the granary where the harvest is gathered, and across the barren soil where famine dwells and skeletons cry for the return of their flesh.

They pass through populous cities humming with life, through dumb desolation bugging its ruined past, and hovels for the unclad and unclean, a mockery of home for the homeless.

They travel through long hours of the summer day, and as the light wanes in the evening they ask the man who reads the sky:

‘Brother, is yonder the tower of our final hope and peace?’

The wise man shakes his head and says:

It is the last vanishing cloud of the sunset.’

‘Friends,’ exhorts the young, ‘do not stop.

Through the night’s blindness we must struggle into the Kingdom of living light.’

They go on in the dark.

The road seems to know its own meaning and dust underfoot dumbly speaks of direction.

The stars celestial way farers sing in silent chorus:

‘Move on, comrades!’

In the air floats the voice of the Leader:

‘The goal is nigh.’

9

The first flush of dawn glistens on the dew-dripping leaves of the forest.

The man who reads the sky cries:

‘Friends, we have come!’

They stop and look around.

On both sides of the road the corn is ripe to the horizon, the glad golden answer of the earth to the morning light.

The current of daily life moves slowly between the village near the hill and the one by the river bank.

The potter’s wheel goes round, the woodcutter brings fuel to the market, the cow-herd takes his cattle to the pasture, and the woman with the pitcher on her head walks to the well.

But where is the King’s castle, the mine of gold, the secret book of magic, the sage who knows love’s utter wisdom?

‘The stars cannot be wrong,’ assures the reader of the sky.

‘Their signal points to that spot.’

And reverently he walks to a wayside spring from which wells up a stream of water, a liquid light, like the morning melting into a chorus of tears and laughter.

Near it in a palm grove surrounded by a strange hush stands a leaf—thatched hut, at whose portal sits the poet of the unknown shore, and sings:

‘Mother, open the gate!’

10

A ray of morning sun strikes aslant at the door.

The assembled crowd feel in their blood the primaeval chant of creation:

‘Mother, open the gate!’

The gate opens.

The mother is seated on a straw bed with the babe on her lap,

Like the dawn with the morning star.

The sun’s ray that was waiting at the door outside falls on the head of the child.

The poet strikes his lute and sings out:

‘Victory to Man, the new-born, the ever-living.’

They kneel down, the king and the beggar, the saint and the sinner, the wise and the fool, and cry:

‘Victory to Man, the new-born, the ever-living.’

The old man from the East murmurs to himself:

‘I have seen!’

3.3. Freedom

Freedom from fear is the freedom I claim for you, my Motherland!—Fear, the phantom demon, shaped by your own distorted dreams;

Freedom from the burden of ages, bending your head, breaking your back, blinding your eyes to the beckoning call of the future;

Freedom from shackles of slumber wherewith you fasten yourself to night’s stillness, mistrusting the star that speaks of truth’s adventurous path;

Freedom from the anarchy of destiny, whose sails are weakly yielded to blind uncertain winds, and the helm to a hand ever rigid and cold as Death;

Freedom from the insult of dwelling in a puppet’s world, where movements are started through brainless wires, repeated through mindless habits; where figures wait with patient obedience for a master of show to be stirred into a moment’s mimicry of life.

3.4. From Hindi Songs of Jnanadas

1

Where were your songs, my bird, when you spent your nights in the nest?

Was not all your pleasure stored therein?

What makes you lose your heart to the sky—the sky that is boundless?

Answer

While I rested within bounds I was content. But when I soared into vastness I found I could sing.

2

Messenger, morning brought you, habited in gold.

After sunset your song wore a tune of ascetic grey, and then came night.

Your message was written in bright letters across black.

Why is such splendour about you to lure the heart of one who is nothing?

Answer

Great is the festival hall where you are to be the only guest.

Therefore the letter to you is written from sky to sky, and I, the proud servant, bring the invitation with all ceremony.

3

I had travelled all day and was tired, then I bowed my head towards thy kingly court still far away.

The night deepened, a longing burned in my heart; whatever the words I sang, pain cried through them, for even my songs thirsted. O my Lover, my Beloved, my best in all the world!

When time seemed lost in darkness thy hand dropped its sceptre to take up the lute and strike the uttermost chords; and my heart sang out, O my Lover, my Beloved, my best in all the world!

Ah, who is this whose arms enfold me?

Whatever I have to leave let me leave, and whatever I have to bear let me bear. Only let me walk with thee, O my Lover, my Beloved, my best in all the world!

Descend at whiles from thine audience hall, come down amid joys and sorrows; hide in all forms and delights, in love and in my heart; there sing thy songs, O my Lover, my Beloved, my best in all the world!

3.5. Fulfilment

The overflowing bounty of thy grace comes down from the heaven to seek my soul only, wherein it can contain itself.

The light that is rained from the sun and stars is fulfilled when it reaches my life.

The colour is like sleep that clings, to the flower which waits for the touch of my mind to be awakened.

The low that tunes the strings of existence breaks out in music when my heart is won.

3.6. Krishnakali

I call her my Krishna flower though they call her dark in the village.

I remember a cloud-laden day and a glance from her eyes, her veil trailing down at her feet her braided hair loose on her back.

Ah, you call her dark; let that be, her black gazelle eyes I have seen.

Her cows were lowing in the meadow, when the fading light grew grey.

With hurried steps she came out from her hut near the bamboo grove.

She raised her quick eyes to the sky, where the clouds were heavy with rain.

Ah, you call her dark! Let that be, her black gazelle eyes I have seen.

The East wind in fitful gusts ruffled the young shoots of rice.

I stood at the boundary hedge with none else in the lonely land.

If she espied me in secret or not

She only knows and know.

Ah, you call her dark! Let that be, her black gazelle eyes I have seen.

She is the surprise of cloud in the burning heart of May, a tender shadow on the forest in the stillness of sunset hour, a mystery of dumb delight in the rain-loud night of June.

Ah, you call her dark! Let that be, her black gazelle eyes I have seen.

I call her my Krishna flower, let all others say what they like.

In the rice-field of Maina village

I felt the first glance of her eyes.

She had not a veil on her face, not a moment of leisure for shyness.

Ah, you call her dark! Let that be.

3.7. The New Year

Like fruit, shaken free by an impatient wind from the veils of its mother flower, thou comest, New Year, whirling in a frantic dance amid the stampede of the wind-lashed clouds and infuriate showers, while trampled by thy turbulence are scattered away the faded and the frail in an eddying agony of death.

Thou art no dreamer afloat on a languorous breeze, lingering among the hesitant whisper and hum of an uncertain season.

Thine is a majestic march, o terrible Stranger, thundering forth an ominous incantation, driving the days on to the perils of a pathless dark, where thou carriest a dumb signal in thy banner, a decree of destiny undeciphered.

3.8. Raidas, the Sweeper

Raidas, the sweeper, sat still, lost in the solitude of his soul, and some songs born of his silent vision found their way to the Rani’s heart, the Rani Jhali of Chitore.

Tears flowed from her eyes, her thoughts wandered away from her daily dudes, till she met Raidas who guided her to God’s presence.

The old Brahmin priest of the King’s house rebuked her for her desecration of sacred law by offering homage as a disciple to an outcaste.

‘Brahmin,’ the Rani answered, ‘while you were busy tying your purse—strings of custom ever tighter, love’s gold slipped unnoticed to the earth, and my Master in his divine humility has picked it up from the dust.

‘Revel in your pride of the unmeaning knots without number, harden your miserly heart, but I, a beggar woman, am glad to receive love’s wealth, the gift of the lowly dust, from my Master, the sweeper.’

3.9. Santiniketan Song

She is our own, the darling of our hearts, Santiniketan.

Our dreams are rocked in her arms.

Her face is a fresh wonder of love every time we see her, for she is our own, the darling of our hearts.

In the shadows of her trees we meet in the freedom of her open sky.

Her mornings come and her evenings bringing down heaven’s kisses, making us feel anew that she is our own, the darling of our hearts.

The stillness of her shades is stirred by the woodland whisper; her amlaki groves are aquiver with the rapture of leaves.

She dwells in us and around us, however far we may wander.

She weaves our hearts in a song, making us one in music, tuning our strings of love with her own fingers; and we ever remember that she is our own, the darling of our hearts.

3.10. Shesher Kobita

Can you hear the sounds of the journey of time?

Its chariot always in a flight

Raises heartbeats in the skies

And birth-pangs of stars

In the darkness of space

Crushed by its wheels.

My friend!

I have been caught in the net

Cast by that flying time

It has made me its mate

In its intrepid journey

And taken me in its speeding chariot

Far away from you.

To reach the summit of this morning

I seem to have left behind many deaths

My past names seem to stream

In the strong wind

Born of the chariot’s speed.

There is no way to turn back;

If you see me from afar

You will not recognize me my friend,

Farewell!

If in your lazy hours without any work

The winds of springtime

Brings back the sighs from the past

As the cries of shedding spring flowers

Fill the skies

Please see and search

If in a corner of your heart

You can find any remnants of my past;

In the evening hours of fading memories

It may shed some light

Or take some nameless form

As if in a dream.

Yet it is not a dream

It is my truth of truths

It is deathless

It is my love.

Changeless and eternal

I leave it as my offering to you

In the ever changing flow of time

Let me drift.

My friend, farewell!

You have not sustained any loss.

If you have created an immortal image

Out of my mortal frame

May you devote your self

In the worship of that idol

As the recreation of your remaining days

Let your offerings not be mired

By the touch of my earthly passion.

The plate that you will arrange with utmost care

For the feast of your mind

I will not mix it with anything

That does not endure

And is wet with my tears.

Now you will perhaps create

Some dreamy creation out of my memories

Neither shall I feel its weight

Nor will you feel obliged.

My friend, farewell!

Do not mourn for me,

You have your work, I have my world.

My vessel has not become empty

To fill it is my mission.

I shall be pleased

If anybody keeps waiting

Anxiously for me.

But now I shall offer myself to him

Who can brighten the darkness with light

And see me as I am

Transcending what is good or bad.

Whatever I gave you

It is now your absolute possession.

What I have to give now

Are the hourly offerings from my heart.

You are incomparable, you are rich!

Whatever I gave you

It was but your gift

You made me so much indebted

As much as you took.

My friend, farewell!

3.11. The Son of Man

From his eternal seat Christ comes down to this earth, where, ages ago, in the bitter cup of death He poured his deathless life for those who came to the call and those who remained away.

He looks about Him, and sees the weapons of evil that wounded His own age.

The arrogant spikes and spears, the slim, sly knives, the scimitar in diplomatic sheath, crooked and cruel, are hissing and raining sparks as they are sharpened on monster wheels.

But the most fearful of them all, at the hands of the slaughterers, are those on which has been engraved His own name, that are fashioned from the texts of His own words fused in the fire of hatred and hammered by hypocritical greed.

He presses His hand upon His heart; He feels that the age-long moment of His death has not yet ended, that new nails, turned out in countless numbers by those who are learned in cunning craftsmanship, pierce Him in every joint

They had hurt Him once, standing at the shadow of their temple; they are born anew in crowds.

From before their sacred altar they shout to the soldiers, ‘Strike!’

And the Son of Man in agony cries, ‘My God, My God, why hast Thou forsaken me?’

3.12. This Evil Day

Age after age, hast Thou, O Lord, sent Thy messengers into this pitiless world, who have left their word:

‘Forgive all. Love all. Cleanse your hearts from the blood-red stains of hatred.’

Adorable are they, ever to be remembered; yet from the outer door have I turned them away to-day-this evil day with unmeaning salutation.

Have I not seen secret malignance strike down the helpless under the cover of hypocritical night?

Have I not heard the silenced voice of Justice weeping in solitude at might’s defiant outrages?

Have I not seen in what agony reckless youth, running mad, has vainly shattered its life against insensitive rocks?

Choked is my voice, mute are my songs to-day, and darkly my world lies imprisoned in a dismal dream; and I ask Thee, O Lord, in tears: ‘Hast Thou Thyself forgiven, hast even Thou loved those who are poisoning Thy air, and blotting out Thy light?’

3.13. W.W. Pearson

Thy nature is to forget thyself; but we remember thee.

Thou shinest in self-concealment revealed by our love.

Thou lendest light from thine own soul to those that are obscure.

Thou seekest neither love nor fame; Love discovers thee.

4. Fruit-Gathering

I

Bid me and I shall gather my fruits to bring them in full baskets into your courtyard, though some are lost and some not ripe.

For the season grows heavy with its fulness, and there is aplaintive shepherd’s pipe in the shade.

Bid me and I shall set sail on the river.

The March wind is fretful, fretting the languid waves into murmurs.

The garden has yielded its all, and in the weary hour of evening the call comes from your house on the shore in the sunset.

II

My life when young was like a flower—a flower that loosens a petal or two from her abundance and never feels the loss when the spring breeze comes to beg at her door.

Now at the end of youth my life is like a fruit, having nothing to spare, and waiting to offer herself completely with her full burden of sweetness.

III

Is summer’s festival only for fresh blossoms and not also for withered leaves and faded flowers?

Is the song of the sea in tune only with the rising waves?

Does it not also sing with the waves that fall?

Jewels are woven into the carpet where stands my king, but there are patient clods waiting to be touched by his feet.

Few are the wise and the great who sit by my Master, but he has taken the foolish in his arms and made me his servant forever.

IV

I woke and found his letter with the morning.

I do not know what it says, for I cannot read.

I shall leave the wise man alone with his books, I shall not trouble him, for who knows if he can read what the letter says.

Let me hold it to my forehead and press it to my heart.

When the night grows still and stars come out one by one I will spread it on my lap and stay silent.

The rustling leaves will read it aloud to me, the rushing stream will chant it, and the seven wise stars will sing it to me from the sky.

I cannot find what I seek, I cannot understand what I would learn; but this unread letter has lightened my burdens and turned my thoughts into songs.

V

A handful of dust could hide your signal when I did not know its meaning.

Now that I am wiser I read it in all that hid it before.

It is painted in petals of flowers; waves flash it from their foam; hills hold it high on their summits.

I had my face turned from you, therefore I read the letters awry and knew not their meaning.

VI

Where roads are made I lose my way.

In the wide water, in the blue sky there is no line of a track.

The pathway is hidden by the birds’ wings, by the star-fires, by the flowers of the wayfaring seasons.

And I ask my heart if its blood carries the wisdom of the unseen way.

VII

Alas, I cannot stay in the house, and home has become no home tome, for the eternal Stranger calls, he is going along the road.

The sound of his footfall knocks at my breast; it pains me!

The wind is up, the sea is moaning. I leave all my cares and doubts to follow the homeless tide, for the Stranger calls me, he is going along the road.

VIII

Be ready to launch forth, my heart! And let those linger who must.

For your name has been called in the morning sky.

Wait for none!

The desire of the bud is for the night and dew, but the blown flower cries for the freedom of light.

Burst your sheath, my heart, and come forth!

IX

When I lingered among my hoarded treasure I felt like a worm that feeds in the dark upon the fruit where it was born.

I leave this prison of decay.

I care not to haunt the mouldy stillness, for I go in search of everlasting youth; I throw away all that is not one with my life nor as light as my laughter.

I run through time and, O my heart, in your chariot dances the poet who sings while he wanders.

X

You took my hand and drew me to your side, made me sit on the high seat before all men, till I became timid, unable to stir and walk my own way; doubting and debating at every step lest I should tread upon any thorn of their disfavour.

I am freed at last!

The blow has come, the drum of insult sounded, my seat is laid low in the dust.

My paths are open before me.

My wings are full of the desire of the sky.

I go to join the shooting stars of midnight, to plunge into the profound shadow.

I am like the storm-driven cloud of summer that, having cast of fits crown of gold, hangs as a sword the thunderbolt upon a chain of lightning.

In desperate joy I run upon the dusty path of the despised; I draw near to your final welcome.

The child finds its mother when it leaves her womb.

When I am parted from you, thrown out from your household, I am free to see your face.

XI

It decks me only to mock me, this jewelled chain of mine.

It bruises me when on my neck, it strangles me when I struggle to tear it off.

It grips my throat, it chokes my singing.

Could I but offer it to your hand, my Lord, I would be saved.

Take it from me, and in exchange bind me to you with a garland, for I am ashamed to stand before you with this jewelled chain on my neck.

XII

Far below flowed the Jumna, swift and clear, above frowned the jutting bank.

Hills dark with the woods and scarred with the torrents were gathered around.

Govinda, the great Sikh teacher, sat on the rock reading scriptures, when Raghunath, his disciple, proud of his wealth, caine and bowed to him and said, “I have brought my poor present unworthy of your acceptance.”

[Transcriber’s note: In the above verse, the word ‘caine’ does not fit in, the word ‘came’ makes more sense]

Thus saying he displayed before the teacher a pair of gold bangles wrought with costly stones.

The master took up one of them, twirling it round his finger, and the diamonds darted shafts of light.

Suddenly it slipped from his hand and rolled down the bank into the water.

“Alas,” screamed Raghunath, and jumped into the stream.

The teacher set his eyes upon his book, and the water held and hid what it stole and went its way.

The daylight faded when Raghunath came back to the teacher tired and dripping.

He panted and said, “I can still get it back if you show me where it fell.”

The teacher took up the remaining bangle and throwing it into the water said, “It is there.”

XIII

To move is to meet you every moment, Fellow-traveller!

It is to sing to the falling of your feet.

He whom your breath touches does not glide by the shelter of the bank.

He spreads a reckless sail to the wind and rides the turbulent water.

He who throws his doors open and steps onward receives your greeting.

He does not stay to count his gain or to mourn his loss; his heart beats the drum for his march, for that is to march with you every step, Fellow-traveller!

XIV

My portion of the best in this world will come from your hands: such was your promise.

Therefore your light glistens in my tears.

I fear to be led by others lest I miss you waiting in some road corner to be my guide.

I walk my own wilful way till my very folly tempts you to my door.

For I have your promise that my portion of the best in this world will come from your hands.

XV

Your speech is simple, my Master, but not theirs who talk of you.

I understand the voice of your stars and the silence of your trees.

I know that my heart would open like a flower; that my life has filled itself at a hidden fountain.

Your songs, like birds from the lonely land of snow, are winging to build their nests in my heart against the warmth of its April, and I am content to wait for the merry season.

XVI

They knew the way and went to seek you along the narrow lane, but I wandered abroad into the night for I was ignorant.

I was not schooled enough to be afraid of you in the dark, therefore I came upon your doorstep unaware.

The wise rebuked me and bade me be gone, for I had not come by the lane.

I turned away in doubt, but you held me fast, and their scolding became louder every day.

XVII

I brought out my earthen lamp from my house and cried, “Come, children, I will light your path!”

The night was still dark when I returned, leaving the road to its silence, crying, “Light me, O Fire! For my earthen lamp lies broken in the dust!”

XVIII

No: it is not yours to open buds into blossoms.

Shake the bud, strike it; it is beyond your power to make it blossom.

Your touch soils it, you tear its petals to pieces and strew them in the dust.

But no colours appear, and no perfume.

Ah! It is not for you to open the bud into a blossom.

He who can open the bud does it so simply.

He gives it a glance, and the life-sap stirs through its veins.

At his breath the flower spreads its wings and flutters in the wind.

Colours flush out like heart-longings, the perfume betrays a sweet secret.

He who can open the bud does it so simply.

XIX

Sudâs, the gardener, plucked from his tank the last lotus left by the ravage of winter and went to sell it to the king at the palace gate.

There he met a traveller who said to him, “Ask your price for the last lotus,—I shall offer it to Lord Buddha.”

Sudâs said, “If you pay one golden mâshâ it will be yours.

The traveller paid it.

At that moment the king came out and he wished to buy the flower, for he was on his way to see Lord Buddha, and he thought, “It would be a fine thing to lay at his feet the lotus that bloomed in winter.”

When the gardener said he had been offered a golden mâshâ the king offered him ten, but the traveller doubled the price.

Tausende von E-Books und Hörbücher

Ihre Zahl wächst ständig und Sie haben eine Fixpreisgarantie.

Sie haben über uns geschrieben: