Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: IVP

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Sprache: Englisch

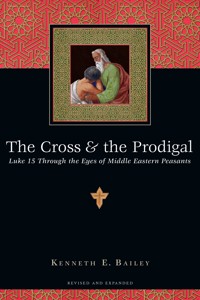

Preaching Magazine Year's Best Book for Preachers Where is the cross in the parable of the prodigal son? For centuries, Muslims have called attention to the father's forgiveness in this parable in order to question the need for a Mediator between humanity and God. In The Cross and the Prodigal, Kenneth E. Bailey--New Testament scholar and long-time missionary to the Middle East--undertakes to answer this question. Drawing on his extensive knowledge of both the New Testament and Middle Eastern culture, Bailey presents an interpretation of this parable from a Middle Eastern perspective and, in doing so, powerfully demonstrates its essentially Christian message. Here Bailey highlights the underlying tensions between law and love, servanthood and sonship, honor and forgiveness that grant this story such timeless spiritual and theological power.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 202

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2010

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

SECOND EDITION

The Cross & the Prodigal

Luke 15 Through the Eyes ofMiddle Eastern Peasants

ToUstaz Nageeb Ibraheemin whose heart shines the lightwhich the night cannot overcome,and the light of whose life has guided methrough much darkness

Contents

Introduction to theSecond Edition

It is almost forty years since I wrote this little book, and it is with joy and much gratitude that I see it reappearing. The editors of InterVarsity Press have invited me to reflect briefly on the journey that the work inaugurated. I count it a privilege to do so.

Andrew Walls, the renowned Scottish historian of non-Western Christianity, has affirmed on numerous occasions that the modern missionary movement launched new academic disciplines. He mentions anthropology and linguistics, along with Asian and African studies. Perhaps there is another discipline that needs to be added to such a distinguished list: Middle Eastern New Testament studies. For many, this proposed field may sound like a contradiction in terms. Isn’t the Middle East the heartland of Islam? What does that world have to do with the New Testament? Is there any data for Middle Eastern New Testament studies?

There are more Arabic-speaking Christians in the Middle East than Jews in the entire world. This demographic fact is generally unknown in the West, where all Arabs are often assumed to be Muslims. The result is that even though there were Arabic speakers present on Pentecost (Acts 2:11), millions of Arab Christians today are almost invisible to the Western world. There are at least three plausible reasons for this reality.

Shortly after World War II, Winston Churchill described the critical divide that had occurred between Eastern and Western Europe as an “Iron Curtain.” In the early Christian centuries, not one but three curtains fell across the Mediterranean basin separating the Middle East from Europe.

The first of these was the Council of Chalcedon (A.D. 451), which resulted in a deep split between the churches of the Greek and Roman worlds on the one hand, and most of the churches of the Eastern Mediterranean on the other. A second curtain fell with the Islamic invasions of the early seventh century. As Islam poured across the Middle East and swept North Africa, Spain and, in time, also Asia Minor and the Balkans, there was a great divide between “the Christian world” and “the Islamic world.” Sadly, Eastern Christians, overrun by powerful Muslim forces, were largely forgotten. A third curtain can be called the linguistic curtain. The primary languages of non-Chalcedonian Eastern Christians have historically been Syriac, Coptic and Arabic. These difficult tongues are rarely learned by New Testament scholars. The result of these three curtains is that Eastern Christianity, with all of its spiritual treasures, remains largely unknown. This means that for roughly 1,500 years we in the West have been interpreting the New Testament with virtually no contact with the Christians of the Eastern Mediterranean who, in a unique way, are inheritors of the traditional culture of the Middle East and thereby the culture of the Bible.

As a Jew, Jesus participated in Middle Eastern culture and its milieu. Yes, Hellenism was a powerful force in Jesus’ day, but his primary languages were Aramaic and Hebrew—not Greek. What difference does all of this make to my exegetical journey through Luke 15 and Middle Eastern culture that this little book begins to document?

My forty-year sojourn among Middle Eastern Christians was in its formative early years when I wrote The Cross and the Prodigal. Throughout those decades I was working, thinking and teaching in Arabic and thus participating in church life as I studied and taught Semitic-based Gospels to predominantly Semitic peoples. Those years ingrained a very deep awareness in me.

If theology is expressed in concepts and structured by philosophy and logic, the primary tools required are a good mind and the ability to think logically. But if theology is presented in story form, the meaning of the story cannot be fairly ascertained without becoming, as much as possible, a part of the culture of the storyteller and his or her listeners. A wonderful illustration of this dilemma is set forth by N. T. Wright in his new book on the Resurrection.1 Wright borrows an illustration from George Caird who records the sentence, “I am mad about my flat.” In the mouth of an American this means, “I am angry because someone has punctured one of the tires on my car.” But for the British the same statement means, “I am very excited about my new living quarters.” The culture of the speaker must be penetrated if what is said is to be understood. Even so with the life and teachings of Jesus. The Spirit has not been without a witness across the centuries. Yet there are layers of perception that can only be uncovered when the culture of the Middle East is understood and applied to the interpretation of Scripture. Luke 15 is a primary example of this truth.

Is it shameful for a young man to ask for his inheritance when his father is still alive? Is it ominous when his older brother remains silent? How is the father expected to respond? Does the youth shame his family in the community by selling his portion of the property? When the son “came to himself” was he “repenting” or “trying to get something to eat?” Why is there no mother in the story? Does the father humiliate himself by running down the road? Can a father leave his guests to go out and talk to an older son who is pouting in the courtyard? If he does, what does it mean? These and many other questions gradually appeared on the screen of my mind as I was privileged to live and learn in the Middle East from my youth through nearly three score years and ten.

This book was my first attempt at taking Middle Eastern culture as a starting point for interpretation of a well-known passage of the Gospels. Granted, no one can simplistically assume that the contemporary Middle East is identical to the first century. But in its conservative traditional villages, the Middle East provided a cultural place to stand where the above questions forced themselves on me and cried out for thoughtful answers. Without that place to stand the questions themselves would not have occurred to me, and consequently I would not have sought their answers. Regardless of its limitation, it was clear to me that Middle Eastern culture was a better lens through which to examine the parables of Jesus than my inherited contemporary American culture.

My study of Luke 15 has evolved in both method and perception. I am conscious of five distinct stages:

1. Traditional Middle Eastern culture. My starting point was the above mentioned privilege of living among and learning from Middle Eastern Christians.

2. Eastern Christian New Testament literature. Early in my study and research I slowly became aware of 1,800 years of translations of the text of the New Testament from Greek into Syriac and Coptic and then into Arabic.

Translation always involves interpretation. Every translation is a minicommentary. The earliest of these translations have been my daily companion for decades. I then discovered the great Syriac commentators on the New Testament, such as Hibatallah ibn al-Assal and Abdallah ibn al-Tayyib. These and other Arabic language scholars remain largely unpublished in any language and thereby unknown beyond a narrow circle in the Middle East. Tens of thousands of exegetical sermons in manuscript form await me.

3. Rabbinics. There is no substitute for original sources. Reading the Mishnah from cover to cover twice was an exciting adventure, partially because as I read I found myself back in the kind of traditional Middle Eastern village of the type I had already experienced. The sense of déjà vu was strong indeed as I read. After that formative exposure to Judaica I could see clearly that the primary structures of daily life, which I had already observed in conservative Middle Eastern village life, could be documented from the sayings of firstand second-century rabbis from Babylon to Jerusalem. Reading most of the twenty-nine volumes of the Babylonian Talmud provided important additional data, as did the Jerusalem Talmud. Living for some years in the world of the ten volumes of the Midrash Rabbah was also rewarding, not to mention the Tosefta and the Targumim.

The issue is not the economic, political and societal changes that are inevitable in any community. Nor do I assume that a third-century rabbinic interpretation of a particular Psalm was necessarily current in the first century. Rather, as I have already written elsewhere,

to interpret the parables of Jesus, the interpreter (consciously or unconsciously) will inevitably make decisions about attitudes toward women, men, the family, the family structure, family loyalties and their requirements, children, architectural styles, agricultural methods, leaders, scholars, religious authorities, trades, craftsmen, servants, eating habits, money, loyalty to community, styles of humor, story-telling, methods of communication, use of metaphor, forms of argumentation, forms of reconciliation, attitudes toward time, toward governmental authorities, what shocks and at what level, reactions to social situations, reasons for anger, attitudes toward animals, emotional and cultural reactions to various colors, dress, sexual codes, the nature of personal and community honor and its importance, and many, many other things.2

Every human being, regardless of his or her culture, has a set of attitudes that shape all of the above. These culturally conditioned attitudes function unconsciously and inevitably influence the way any person reads any story. It is my Middle Eastern experience of these things, confirmed through a serious reading of early rabbinic sources, that has provided me with an escape hatch from my own Western cultural imprisonment.

4. Psalm 23. As my journey through the mind of Jesus the rabbi continued, I gradually came to see that the parable of the lost sheep in Luke 15:3-7 was a “rewrite” of the beloved Shepherd’s psalm. Following this lead, I discovered many new treasures in the parable.3

5. Jacob. At times one stumbles onto a new discovery when not looking for it. Such was the case when I listened to a very astute lecture on the story of Jacob during which the penny dropped. Stimulated by that lecture, I gradually became aware of fifty-one points of comparison and contrast between the story of Jacob in Genesis 27:1—36:8 and the parable of the prodigal son. In constructing the great parable of the two lost sons, Jesus was clearly rewriting the primary story that gave Israel its name and its identity.4

Another aspect of the importance of this great parable is the subject of Christian witness to or dialogue/confrontation with Islam. September 11, 2001, and its aftermath have brought Christianity and Islam face to face in far more critical ways today than was the case forty years ago. Islam continues to read the parable of the prodigal son as a denial of both the incarnation and the atonement. (On the surface it appears that the prodigal is reconciled to his father by his own unaided efforts. If so, Jesus reflects Islamic theology in this parable.) The Cross and the Prodigal tries to bring some answers to this challenge.

For me, a decades-long journey began with this book. Is it a “voice crying in the wilderness”? Perhaps. I hope not. Will other voices, more able than mine, appear that can plumb more deeply the Eastern cultural world and more precisely interpret the inexhaustible richness of stories from and about Jesus? I earnestly hope so. Is this cautious, unsteady step a possible beginning to a new discipline that might one day be christened “Middle Eastern New Testament Studies”? I don’t know. All I can do is hope that once again your young men shall see visions,

and your old men shall dream dreams. (Joel 2:28; Acts 2:17)

A final word is perhaps in order regarding the drama that is part of this work. If “story” is a serious mode of theological language that effectively creates meaning, then emotion and drama cannot be ignored. The difficulty is that contemporary “biblical drama” often overlaps with fiction, and in the process the fiction overwhelms the biblical text and its message. As this happens drama becomes a deliberately crafted tool for presenting the ideas of the dramatist in violation of the vision of the biblical author.

I have written the scripts for two professionally produced feature-length films; one of which is based on the three parables of Luke 15.5 In the yearlong process of script revision for the latter and during the filming itself, I found myself under constant pressure to ignore the perceived ideas of Jesus and allow the drama to present the ideas of the film director. With the backing of the film’s producers this leverage was successfully resisted, but it was always there. Perhaps such pressures have historically helped keep serious biblical interpretation and biblical drama apart. In addition, it may not have occurred to many that a good story engages the emotions and that drama can be disciplined to serve the purposes of serious exegesis.

It is my hope that others will be inspired to venture down this often neglected path. From the first I was determined to unite serious exegesis and serious drama. They belong together. The reader will be the judge of the success or failure of this wedding.

Yes, “a journey of a thousand miles begins with one step.” A corollary to that famous phrase is “the first step must be in the right direction.” Looking back I sense that the “first step” made by this modest effort was in the right direction.

My prayer, gentle reader, is that these three parables of Jesus, here clarified, may encourage you in your journey of faith even as they have encouraged me in mine.

“He was dead and is alive.

He was lost and is found.”

Kenneth E. Bailey

Preface

Across the centuries since the rise of Islam, Muslim voices have echoed the cry “Christians have perverted the message of Jesus” and pointed to the famous parable of the prodigal son as evidence. Their case can be stated as follows:

In this parable the Father obviously represents God while the younger son represents humankind. The son leaves home, gets into trouble and finally decides to return to his Father. He “yistaghfir Allah” (he seeks the forgiveness of God). On arrival the Father welcomes the son and thus demonstrates that he, the father, is “rahman wa rahim” (merciful and compassionate). There is no cross and no incarnation, no “son of God” and no “savior,” no “word that becomes flesh” and no “way of salvation,” no death and no resurrection, no mediator and no mediation. The son needs no help to return home. The result is obvious. Jesus is a good Muslim who in this parable affirms Muslim theology. The heart of the Christian faith is thus denied by the very prophet Christianity claims to follow. Islam with neither a cross nor a savior preserves the true message of the prophet Jesus.

Arab Christians in the Middle East have grappled with this crisis of interpretation for more than a millennium. In various forms the modern world now faces the same crisis. As a result of emigration and a series of international conflicts, the interface between Christianity and Islam is upon us, ready or not! What can be said about this reality?

R. C. Trench in his famous Notes on the Parables of Our Lord observes that for centuries the story of the prodigal son has been called Evangelium in Evangelio (the gospel in the Gospel). Trench affirms that this title is abundantly justified.1 If across the centuries this is the way the church has seen this parable, how is it that both the incarnation (God comes to us in Jesus) and the atonement (the cross is a saving power) appear to be missing? If the cross is essential for forgiveness, why does it seem to be absent in this parable? Having spent four decades serving the Arab Christian churches of the Middle East, these and other related theological questions have required answers of me. A part of this book is a summary of the answers I have found to the above challenge.

I have discussed the three parables of the lost sheep, the lost coin and the two lost sons (the prodigal son) extensively with scholars, pastors, elders, and illiterate farmers across the Arab world, and I have struggled to understand it in its Middle Eastern cultural setting. In addition I have followed the centuries-old commentaries on the Gospel of Luke written in Arabic and Syriac, along with the commentaries on these parables in the Western tradition. The relevant early literature of the Jewish community in the Mishnah and the two Talmuds have been scrutinized as well. Half a century of study has produced for me a series of new insights as I tried to see these parables through Middle Eastern eyes.

The result has been a new way to talk about the heart of our faith that can speak to the Muslim mind of the East and hopefully to the secular mindset of the West. It is my prayer that it may also be of use in explaining the Christian faith in the global South.

For years music has aided immeasurably in communicating the emotional content of the Psalms. Part two of this book is a drama that seeks to express the theological and the emotional content of this parable. The play Two Sons Have I Not is written both to be read (privately or publicly) and acted. For centuries dramatists have taken biblical stories and shaped them to describe their own ideas, often deliberately ignoring the intent of the biblical authors. This is not my goal. Rather, this play tries to present, in dramatic form, theological content that I am convinced is placed in the story by its original composer, Jesus of Nazareth. Those who shared his culture would have had these ideas available to them directly in the parable itself. For people of other times and cultures the drama hopefully can help clarify and communicate that same meaning along with the dramatic tensions and the emotions that are at the heart of the story.

Jesus spoke to a Middle Eastern peasant people. Even the educated would have had their roots in that peasantry. What lies between the lines, what is felt and not spoken, is of deepest significance. Indeed, it almost cannot be expressed because it is not consciously apprehended. What “everybody knows” is never explained.

In the Middle East “everybody knows” that to be polite to your father is much more important than to obey him. Jesus disagrees. So he tells a story of a father and his two boys in which he declares that the good son is the son who obeyed, even if he was rude to his father (Matthew 21:28-32). When we do not know the underlying village attitudes, it is easy to miss the revolutionary nature of the parable.

The Middle Eastern peasantry has survived through the ages almost unchanged. In isolated villages, I have found young girls making clay dolls that look much like the fertility goddesses of Old Testament times. Patterns of speech, dress and family structure remain stubbornly the same. Father Henry Ayrout, in his famous anthropological monograph on the Egyptian peasant titled The Fellaheen, writes:

The fellaheen have changed their masters, their religion, their language, and their crops, but not their manner of life. . . . [V]iolent and repeated shocks have swept away whole peoples, as can be seen today from the ruins of North Africa or Chaldea, . . . but the fellaheen have held firm and stood their ground. . . . They are as impervious and enduring as the granite of their temples and as slow to develop. . . . This is not merely an impression. We can see the fellah using the same implements—the plough, the shaduf, the saqia, . . . the same methods of treating the body, . . . many of the same marriage and funeral customs. Through the pages of Herodotus, Diodorus Siculus, Strabo, Maqrizi, Vansleb, Pere Sicard and Volney, we can recognize the same fellah. No revolution, no evolution.2

Almost everyone, ancient or modern, who has had the privilege of working over an extended period in villages of the Mideast testifies to the same fact: the granitelike conservatism of the peasantry. Today one of the highest compliments one villager can give to his fellow is the title “Preserver of the Customs.” As a result, in the main, village attitudes are of great antiquity.

When a Japanese Christian artist paints a portrait of the Madonna and child, the figures look Japanese. If one would insist on literalism, the figures are “distorted” by community and culture. Still the picture communicates something essential and meaningful. Indeed, the Japanese distinctives are what give the painting its significance. Western understandings of the Scriptures are likewise conditioned by Western history and culture. There is no escape. I cannot push the bus on which I am riding. No one, in any culture, is a disembodied eye looking down on the world from outer space. If then a cultural “coloring” is inevitable, why not seek it in a peasant society as close to first-century Palestine as possible? The only alternative for all of us who hail from outside of the Middle East is to fall back on our own cultural perceptions. The only eyes I have through which I can view the world are my own. It is the basic presupposition of this study that the insights gained from looking at the parable of the prodigal son through the eyes of conservative Middle Eastern peasant society (ancient and modern) are a better starting point than the cultures of North America or Europe.

In this study, volumes of traditional material, critical and expository, have been omitted. Nor have I tried to interact with the various contemporary commentators on these parables. The emphasis of this book is on new insights.

Jesus spoke Aramaic, Hebrew and certainly some Greek. Whether Luke’s sources for the parables were Greek or Aramaic, written or oral, I will not try to debate here. Yet at a few points I will refer to the twelve-hundred-year-old Arabic Bible tradition that is a lake into which interpretive streams from Coptic, Greek and Syriac have flowed. This Arabic translation tradition is almost unheard of and thereby unexamined.

Across the twentieth century in biblical studies, forms of speech were taken very seriously. Here again village speech forms are also enlightening and will be referred to when appropriate.

All biblical quotations are from the Revised Standard Version or from my own translations of the original Greek.

Arabic calligraphy has been an art form in the Middle East for over a thousand years. Islam forbids the use of any human or animal form in religious art. Decorative writing often fills the gap created thereby. Muslim artists only beautify the text. In the plates that introduce the chapters I have tried to take this art form one step further by attempting to represent symbolically something of the text’s meaning. Each plate has its accompanying translation and commentary.

Wherever possible I have made the language inclusive but occasionally have used he for he and she when the latter is awkward in sentence construction. This is for clarity only and no disrespect to any reader is intended.