8,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

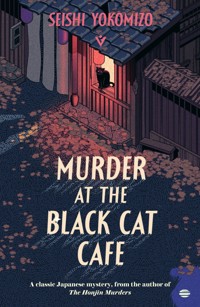

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Vertigo

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

An ingenious and highly atmospheric classic whodunit from Japan's master of crime. Amid the rubble of post-war Tokyo, inside the grand Tsubaki house, a once-noble family is in mourning. The old viscount Tsubaki, a brooding, troubled composer, has been found dead. When the family gather for a divination to conjure the spirit of their departed patriarch, death visits the house once more, and the brilliant Kosuke Kindaichi is called in to investigate. But before he can get to the truth Kindaichi must uncover the Tsubakis' most disturbing secrets, while the gruesome murders continue... PRAISE FOR SEISHI YOKOMIZO 'The diabolically twisted plotted is top-notch' New York Times Readers will delight in the blind turns, red herrings and dubious alibis... Ingenious and compelling' Economist 'Plenty of golden age ingredients... with a truly ingenious solution' Guardian, Best New Crime Novels

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

PRAISE FOR SEISHI YOKOMIZO’S MYSTERIES

‘Readers will delight in the blind turns, red herrings and dubious alibis… Ingenious and compelling’

ECONOMIST

‘At once familiar and tantalisingly strange… It’s an absolute pleasure to see his work translated at last in these beautifully produced English editions’

SUNDAY TIMES

‘The perfect read for this time of year. Short and compelling, it will appeal to fans of Agatha Christie looking for a new case to break’

IRISH TIMES

‘This is Golden Age crime at its best, complete with red herrings, blind alleys and twists and turns galore… A testament to the power of the simple murder mystery and its enduring appeal’

SPECTATOR

‘The diabolically twisted plotting is top-notch’

NEW YORK TIMES

‘A stellar whodunit set in 1940s Japan… The solution is a perfect match for the baffling puzzle. Fair-play fans will hope for more translations of this master storyteller’

PUBLISHERS WEEKLY, STARRED REVIEW

‘With a reputation in Japan to rival Agatha Christie’s, the master of ingenious plotting is finally on the case for anglophone readers’

GUARDIAN

‘A delightfully entertaining locked room murder mystery… An ideal book to curl up with on a winter’s night’

NB MAGAZINE

‘Never anything less than fun from beginning to end… Truly engrossing’

BOOKS AND BAO

‘A classic murder mystery… Comparisons with Holmes are justified, both in the character of Kindaichi and Yokomizo’s approach to storytelling—mixing clues, red herrings and fascinating social insight before drawing back the curtain to reveal the truth’

JAPAN TIMES

‘The perfect gift for any fan of classic crime fiction or locked room mysteries’

MRS PEABODY INVESTIGATES

Contents

Characters

THE INVESTIGATORS

THE TSUBAKI HOUSEHOLD

THE SHINGU HOUSEHOLD

THE TAMAMUSHI HOUSEHOLD

THE KAWAMURA HOUSEHOLD

The story you will read over the next thirty chapters is fiction. Some who read it may well be reminded of certain, similar incidents. I would like to assure everyone that those incidents have nothing at all to do with this story.

the author

CHAPTER 1

The Devil Comes and Plays His Flute

As I take up my pen to begin recording this miserable tale, I cannot help but feel some pangs of conscience.

To tell the truth, I do not want to write it. I have no pleasure in putting down in words all the misery it holds. The events I am about to describe are filled with such darkness and sadness, are so cursed and hate-filled, that not a word I write can possibly offer the faintest glimmer of hope or relief.

Even as the author, I cannot predict what the final sentence will be, but I fear that the relentless dread and darkness that precede it may end up overcoming the readers and crush their very spirits in its grasp. By their nature, stories of crime and mystery leave little enough good feeling in their wake, but this case in particular is so foul that even I feel it is perhaps too extreme. On that point, it seems that Kosuke Kindaichi and I are in agreement. When I asked him to provide me with his case files, he was hesitant about agreeing.

In truth, I should have written about this case before two or three other Kindaichi adventures I have published in the last few years. The reason it comes so late is that Kindaichi was reluctant to reveal its secrets to me, and that was mostly likely because he was afraid that unveiling the unrelenting darkness, twisted human relationships and bottomless hatred and resentment within might discomfit readers.

However, as the booksellers grow louder in their demands, I have resolved to offer up—with Kindaichi’s full agreement—the whole story. Naturally, despite my protests over its writing, and the fact that it gives me no pleasure to do so, now that I have taken up the task I will give this case everything it deserves.

As I write this now, my desk is covered with all the various materials Kosuke Kindaichi provided me, but among them the two objects that stir my heart most are a photograph and a single-sided vinyl record.

The photograph is roughly postcard size. It features the half-length portrait of a gentleman in his middle years. When it was taken, the subject was forty-two years of age. (As an aside, all the ages given in this story are kazudoshi in the traditional way of counting—meaning the child is born one year old, and a year is added on every New Year’s Day. The reason being, when this incident occurred, Japan had not yet adopted the Western style of figuring age.) Forty-two is, as they say, an unfortunate age for men. Perhaps it is the influence of that superstition, or thoughts of the horrific incident I am about to recount, but as I look on the picture, I sense a heavy shadow lying over the man’s countenance.

His complexion is perhaps somewhat dark. His forehead is broad, and his hair parted neatly on the left. He has a proud nose, a furrowed brow and dark eyes that look as if they are troubled by some internal turmoil, a discord hidden forever within. His mouth is small, with lips on the thin side, though they do not give any impression of harshness. Rather, there is a femininity or weakness about them. Even so, his jaw is quite prominent, hinting that beneath the apparent fragility exists a powerful will that could burst forth with sudden violence if pressed. He wears a plain suit, but the bolo tie hanging down his chest reveals a certain artistic sensibility. So, the impression of the picture as a whole is that of an aristocratic, relatively handsome man, but who could he be? He is, in fact, a key figure in this horrific incident, the former viscount Hidesuke Tsubaki. It was just six months after this picture was taken that Tsubaki made his fateful disappearance.

The other item that draws my attention so powerfully is a ten-inch vinyl record published after the war by the G— record company, of a flute solo entitled “The Devil Comes and Plays His Flute”.

The composer and flautist both are that same Hidesuke Tsubaki. In fact, the composition was completed, and the performance recorded just one month before his disappearance.

I do not know how many times I played this record before I began to draft this story. And no matter how many times I listen to it, I cannot help but be struck by the creeping dread that fills it. That is not solely due to any associations with the story I am about to recount. The melody itself is somehow eerie, with an unfamiliar distortion in the key. It transforms the basic melody, which is itself full of darkness, into something deranged and terrifying.

I am no kind of musical expert, but there is something about this piece that reminds me of Doppler’s flute song “Fantaisie Pastorale Hongroise”. However, while Doppler’s work is rather merry, Tsubaki’s “The Devil Comes and Plays His Flute” is filled with misery and heartbreak from start to finish. And the crescendo section is so frenzied that even an utterly tone-deaf listener like me cannot not help but feel my skin crawl, as if I were listening to the enraged, wretched shrieks of dead souls sounding out across the midnight sky. “The Devil Comes and Plays His Flute”…

The name is clearly a reference to the line “The blind man comes and plays his flute” from Mokutaro Kinoshita’s poem, “Harimaya”. However, this piece contains not a hint of the sentimentality that Kinoshita’s poem does. Its sound is the shriek of the devil’s flute, as the name so aptly indicates. It is a melody of bitter hatred, as if it were drenched in foul blood.

If even someone as unfamiliar with the music as I can feel that unnaturalness, I can only imagine the shock and horror that must have filled those connected to the incident each time they heard this piece begin playing out of nowhere after Tsubaki’s disappearance. Given the eerie melody and the events I am about to recount, it is indeed quite easy to imagine.

“The Devil Comes and Plays His Flute”… Looking back, this piece of twisted music always held the key to unlocking the mysteries central to the horrors I am about to recount.

The year of these incidents, 1947, was one that kept the newspapers busy. I can recall at least three major events that caught the public’s attention that year. The connections between two of them are already commonly known, but the strange thing is that the third, which everyone assumed to be totally unrelated, was actually deeply connected, if less openly.

I am referring here to the horrific Tengindo Incident, a crime which sent shockwaves throughout Japan.

Tengindo! I am sure that even just seeing the name written sends chills down the reader’s spine. What happened was so shocking that surely everyone can recall it, even today.

There is likely no need to go into the details, which even the foreign press called “unprecedented in the history of crime”, but I will still give a brief outline. It was 15th January of that year, at around ten o’clock in the morning. A lone man showed up at Tengindo, a jewellery shop famous even for luxurious Ginza. The man was around forty years old, his complexion somewhat dark. He gave the impression of an aristocratic, relatively handsome man, but on his arm was a city health officer band, and in his hand a bag like that a doctor would carry.

He went to speak to the manager in his office at the back of the shop and showed a business card from the Tokyo Department of Health, bearing the name Ichiro Iguchi. He claimed that someone in the area had been spreading an infectious disease, and that he would need all staff who had been in contact with customers to take some preventive medicine.

Later, some would argue that the manager and his staff had been too eager, in ways reminiscent of the war, to blindly obey a government official, but this man calling himself Ichiro Iguchi presented such a calm, reassuring demeanour and respectable character, that no one saw any cause for suspicion.

The manager immediately called his staff into the office. Since it was still too early to expect customers, and the staff were already done arranging the showcases, every member rushed in when called. The cleaning crew from the back even came too, and in the end thirteen people all told, including the manager, crowded into the room together.

When he saw that everyone was present, the monster calling himself Ichiro Iguchi took two bottles from his bag and mixed some of the contents from both into enough teacups for everyone. He then told them to drink. Totally unaware of the horrible fate that was only seconds away, those good folk did as they were instructed and drank the mixture. Within moments, they were afflicted with all the miseries of hell.

The cups had contained potassium cyanide. The staff fell like dominoes, collapsing where they stood. Some stopped breathing as soon as they did, while others lingered on, moaning and gasping in despair.

The monster Iguchi looked on his work, then gathered up his things. He fled the manager’s office and grabbed a handful of the jewels on display, then disappeared into the bustling Ginza streets. The intense investigation that followed revealed that his theft was shockingly small, amounting to only some 300,000 yen in value.

The gruesome crime was discovered just ten minutes after the murderer fled, when a customer happened to come into the shop and, hearing unusual sounds and cries for help from behind a door in the back, looked inside. The discovery sparked an unprecedented commotion.

Of the thirteen victims, only three were saved. The other ten, I regret to say, passed away before the police or doctors could arrive. And so, that is what became known as the Tengindo Incident. The planning of this crime was so simple and effective that it could have gone down in the annals of crime history as a work of genius. However, the brutal, cold-blooded viciousness of it shocked the public like none other, even in those wicked days after the war’s end.

And although the extreme nature of the crime at first suggested it would be a simple matter to find the murderer, this proved to be untrue. The police were unable to track him down, and so the incident took on an even greater power over the public mind.

Naturally, the police held nothing back. They followed every lead in trying to find the criminal, tracing his flight after the murder and even uncovering where the Ichiro Iguchi business card had come from. They were able to create a photo composite, based on interviews with the three surviving victims and two or three witnesses who saw him burst out of Tengindo, and used it to enlist the help of the public at large. The appearance of that composite during the manhunt helped put this case I write about in motion. It was edited and improved five times, and each time every newspaper in the country published it anew. All the various little tragedies that resulted are likely still fresh in the public mind.

The composite triggered a flood of letters and anonymous tip-offs to police. The sheer volume sent the police into chaos as they followed up on every letter that came in saying that “so-and-so in such-and-such village looks just like the picture”. Even though they knew most leads would end up a bust, the detectives had to approach each one as if it were a real chance. They contacted all of the identified people to come in for questioning.

There were also quite a few cases where police officers on the street grabbed someone because he resembled the picture, which caused its own sort of trouble. This was not just in Tokyo, either. It was a nationwide frenzy.

This is where we will find the connection to the story I am going to relate in these pages.

As I wrote before, the Tengindo Incident took place on 15th January, and some fifty days later, on 5th March, the morning paper featured another story that caught the eye. It was a prelude to all the horrific things that followed.

This was all before Osamu Dazai wrote his work Setting Sun, about the decline of the aristocratic class after the war, so we did not yet have ready terms like “the sunset clan” or “sunset class” to describe these people, newly bereft of their noble privilege and falling into ruin. But, if we had, then I think it likely that this case would have been the first to see the term used.

The 5th March morning edition reported that Viscount Hidesuke Tsubaki had apparently vanished. This affair was the first public glimpse into the aristocratic class’s sad fall, so of course the world was fascinated. Viscount Tsubaki had actually disappeared four days previously, on 1st March. At ten o’clock in the morning, the viscount wandered out of his house without a word of explanation to his family, and never returned. When he left, he wore a plain grey overcoat over an equally plain grey suit, and an old fedora on his head.

The family at first did not believe he had actually vanished. Or rather, they did not wish to believe it, so they waited for two days, then three. Of course, during that time they did try contacting various friends and family to try and track down his whereabouts, but they learned nothing. Finally, on the afternoon of the fourth day they filed a missing person’s report with the police, and that was the first public hint of the tragedy to come.

There was no note, but from the viscount’s reported attitude around the time in question, everyone felt the most likely explanation was suicide, so the police department issued a nationwide alert and had his picture published in the morning papers the next day. The picture they used is the same one that now rests on my desk.

Given the lack of a note, even if his disappearance was due to suicide, there was no hint as to his reasons. However, it was not difficult for people to imagine one.

The viscount had apparently lacked the vitality necessary to deal with all the changes and turmoil rocking Japanese society at the time. He was a gentle, somewhat delicate and polite gentleman, to such an extent that he seemed almost completely unequipped for daily life. He had held a middling position with the Ministry of the Imperial Household until the end of the war, but lost it when the ministry was scaled down and replaced with the Imperial Household Agency.

Some also said that the situation at his home was the reason for the disappearance.

The viscount’s mansion in Azabu Roppongi survived the firebombing of Tokyo, but that fact ended up bringing him no end of misery. After the war, his wife’s brother the Viscount Shingu had moved onto the estate with his family after his own house burnt down, as did his wife’s uncle Count Tamamushi and his mistress. Those around Tsubaki said that this situation was simply too much for the sensitive viscount’s nerves.

The estate in Azabu Roppongi was Viscount Tsubaki’s home; however, in point of fact the property remained in his wife Akiko’s name.

The Tsubaki family was a noble one, and one of the most prominent of the old aristocratic lines, but it had produced no notable members since the Meiji Restoration of 1868, and although the family had received titles from the Imperial family, their yearly stipend had dwindled. In Hidesuke’s youth they had been reduced to poverty, and he himself had struggled to maintain the basic appearance necessary for a man of his station. He had been saved by his marriage to a member of the Shingu family.

Akiko’s family, the Shingus, were peers of the old feudal daimyo lineage rather than of the ancient court nobility, and even among the aristocracy, were famous for their wealth. And what is more, the Shingu family were backed by the even greater personage of Count Tamamushi. He was Akiko’s maternal uncle and had been a leader of the House of Peers and a guiding force of the influential Kenkyukai parliamentary faction. He had never taken a ministerial role himself but had always remained a powerful political force in the shadows.

Hidesuke Tsubaki had often wondered why Count Tamamushi would assent to letting his darling niece marry a man such as him, and there were rumours that the count eventually came to regret the marriage, accusing the viscount of being an incompetent, impotent weakling who spent all his time blowing on a flute.

To a forceful, obstinate man like the count, someone like Tsubaki with no concerns for social influence or ambitions at all, must have seemed utterly ineffectual indeed. Yet when that same man looked on his nephew Toshihiko Shingu, who filled his life with liquor, women and golf, the count praised him as being a true figure of nobility. That should indicate just what kind of man Count Tamamushi was.

The wilful count and dissolute brother-in-law came into Viscount Tsubaki’s house and began denigrating him as an incompetent almost immediately. Those who knew him spoke of how even the mild-mannered Tsubaki was pushed beyond the limits of his tolerance.

Putting all of that aside, when Viscount Tsubaki’s whereabouts were still unknown and the newspapers still filled with the news, his record company saw the opportunity and attempted to cash in by releasing the recording of “The Devil Comes and Plays His Flute”. As I have mentioned, that work was actually filled with great meaning, but no one at the time recognized the fact. What’s more, as a particularly sombre flute solo, rather than a more accessible popular song, it was simply not very well received.

No one learned what had become of Hidesuke Tsubaki for nearly two months, although many were already certain of his suicide. After the war ended he had spoken often about death, and said that if he had to die, it would be best to do so quietly alone somewhere in the mountains, where no one would find his remains. Which, it seems, is what he tried to do.

On 14th April, forty-five days after Tsubaki left his family home, his body was discovered in the woods covering Mount Kirigamine in Nagano Prefecture. The police had made a preliminary identification based on his clothing and belongings, and a message was sent immediately to the house in Roppongi.

When word arrived, there was some dispute within the household over who would go to claim the body. The shock of his disappearance had weakened the viscount’s wife Akiko terribly, and indeed she was not by nature particularly well suited to such things, so everyone decided that their daughter Mineko would go instead, and her cousin Kazuhiko said he would accompany her. He was Hidesuke’s nephew, but on top of that he had also been the man’s flute student.

Still, it would not do to send the pair alone, as they were much too young. Kazuhiko was twenty-one years old, while Mineko was only nineteen. They would need someone with more experience of the world to go with them. The family agreed that Kazuhiko’s father Toshihiko would be best suited, but he himself was reluctant. He mocked his younger sister, saying that he would rather find a high-class prostitute or someone to play golf with, than go to claim his brother-in-law’s body.

In the end, though, Akiko’s insistence and the promise of a decent bit of pocket money for a night on the town convinced him to go. The three were also joined by young Totaro Mishima, the orphaned son of Hidesuke’s friend, whom he had taken in after the war. In fact, it was he who dealt with all of the red tape when they arrived on the site, and did so very efficiently.

The body was autopsied and then taken for cremation in the town of Kamisuwa, near where it had been found, but what shocked everyone was that even though the surroundings and the inquest both suggested that Hidesuke had gone to his place of death and taken cyanide directly after leaving his home on 1st March, the body had barely begun to decompose. Naturally, his appearance was not quite what it had been when he was alive, but his daughter, nephew and ward were all three able to identify the corpse at a single glance. Presumably, that unusual preservation had something to do with the cold local climate where he was found.

And so, Hidesuke Tsubaki left this world. If he had indeed died on 1st March, he had done so still a viscount, before Japan’s new constitution abolished the peerage on 3rd May. We must assume that Tsubaki had decided that he would die a member of the aristocracy, as he had lived. Everyone thought that this discovery had closed the case of Viscount Hidesuke Tsubaki’s disappearance. However, it turned out that they were mistaken.

Some six months later, the devil came in truth, blowing his cursed flute with wild abandon, and the world had cause to look at the disappearance again from a new angle.

CHAPTER 2

Viscount Tsubaki’s Parting Note

Kosuke Kindaichi’s lifestyle in 1947, the twenty-second year of the reign of the Showa Emperor, was a strange one.

He had been discharged from the army only the previous autumn, and without a home to return to had settled at the Pine Moon Inn, a kappo ryokan—a traditional lodging specialized in dining—in the Yamanote area of Omori, Tokyo. An old friend of Kindaichi’s, Shunroku Kazama, had become a successful general contractor in Yokohama after the war, and he put his mistress in charge of the ryokan. Kindaichi ended up staying in a room there and settled down like he’d grown roots.

Luckily, his friend’s mistress was a kind woman, and she took to looking after him like he was her own younger brother—though, in fact, she was the younger of the two. Kosuke Kindaichi was an energetic man of action when he was on a case, but the rest of the time he was as indolent as a cat. That meant he required quite a lot of care as a tenant, but the mistress never made a single complaint, and even went so far as to offer him a bit of pocket money. Kindaichi took full advantage of this and settled in like a stone in mud. As comfortable as he was, though, there were occasional difficulties.

One of these was that, as his reputation spread, more and more clients came to ask for help, both men and women. Even the men were often hesitant to visit him in his private rooms, but for older women in particular, it took quite a lot of courage to step alone through the door of that out-of-the-way ryokan. Then, having mustered that bit of courage and gone through the gate, they found themselves in a small room in an isolated annexe building only about four and a half tatami mats in size, squeezed in with Kosuke Kindaichi. It was not a comfortable situation.

The visit that began this case was on 28th September 1947.

Kosuke Kindaichi sat across from a discomfited woman in that same small annexe room. She looked to be around twenty years old. She wore a pink cardigan sweater over a crêpe de Chine blouse with a black skirt. Her hair was cut short, and overall she was quite plainly dressed for a modern young woman.

It would have been hard to call her a beauty, with her prominent forehead over too-large eyes, and cheekbones and chin that were too small. On balance, her whole face seemed out of proportion. It made her look almost foolish, yet at the same time she gave off an aura of great pride. Her air of irritation was not unusual for Kindaichi’s clients, who were often unhappy at being forced into such a position, but that didn’t explain the dark shadow that seemed to envelop her whole body. They sat in silence.

He observed the woman closely, but from his guest’s perspective it likely seemed he was just sitting there calmly puffing on his cigarette. She, on the other hand, sat uncomfortably. She seemed at a loss as to how best to break the silence, and occasionally fussed at her knees. After their initial exchange of greetings, Kindaichi waited for his guest to open up, while she seemed to be waiting for him to draw her into conversation. He was, sadly, not at his best at times like this.

Suddenly, the ash from his cigarette, grown long in the silence, fell from the tip. The woman stared at the fallen ash on the tabletop, her eyes wide in surprise.

“Um—” she started, just as Kindaichi let out a breath, and the ash puffed into the air.

“Oh!” she cried out, and pressed her handkerchief to one eye.

“Oh, no, I-I’m so sorry. Did it get in your eye?” Kindaichi hurriedly bent forward across the table.

“No, no…” The woman rubbed strongly at her eye once or twice, then quickly pulled her handkerchief away and gave him a small, chiding smile. The smile revealed charmingly discoloured teeth. For that moment, at least, the dark shadow wrapped around her seemed to lighten just a little.

Kindaichi rubbed at his shaggy head and said, “I-I beg your pardon. How clumsy of me. Is your eye all right?”

“Yes, it’s quite fine, thank you,” the woman said, her original pride restored. She was clearly straining to maintain a diplomatic tone, but at last they had found room to speak.

“So, you talked to Chief Inspector Todoroki at the police station, I hear?” Kindaichi asked.

“I did, yes.”

“And he said you should come to me?”

“That’s right.”

“Well then, what can I do for you?”

“Oh, well…” The woman hesitated a moment. “My name is Mineko Tsubaki.”

“Yes, you said that earlier.”

“I’m sorry, of course you wouldn’t realize from just my name. My father was Hidesuke Tsubaki. The Tsubaki who disappeared last spring?”

“A disappearance last spring…” Kindaichi muttered to himself for a moment, then his eyes widened. “You mean Viscount Tsubaki?”

“Yes, though he would no longer be a viscount, or anything else…” Mineko said, her voice cold, almost self-mocking, and she stared squarely at Kindaichi with wide eyes. He scratched furiously again at his tousled hair.

“Well, well, well… That’s really something.” Kindaichi frowned as he looked closely at the woman’s face. “But what brings you to me now?”

“Yes, of course, that’s… Well…” The dark shadow enveloping Mineko’s body seemed to grow more intense, as did her aura of frustration. She twisted her handkerchief between her fingers in irritation and said, “I know that this story may sound silly, but for us, it’s deadly serious.”

She looked sharply at Kindaichi, and it was as if her overlarge eyes were drawing him in. “I wonder if my father truly is dead.”

Kindaichi gaped in surprise and jerked as if an intense shock had run through his body. He gripped the sides of the table as if to steady himself and asked, “Wh-why do you say that?!”

Mineko folded her hands primly on her knees and stared at him in silence. The shadow wrapped around her seemed to swell and billow like dark flames. Kindaichi took up his cup and sipped at the tea, long gone cold, to calm himself.

“From what I read about that case in the papers, they found your father’s body in the mountains somewhere in Nagano, didn’t they?”

“Yes, on Mount Kirigamine.”

“How many days was that after he left your house, again?”

“It was the forty-fifth day.”

“I see, so then the body must have been quite badly decomposed and hard to identify. But I thought the newspapers said he was clearly recognized as the Viscount Tsubaki.”

“Oh, no, the body had barely decomposed at all. It was almost disturbing, how little it had.”

“Then you viewed the body yourself?”

“Yes, I claimed his remains. My mother didn’t wish to.”

There was a hint of darkness in her tone when she said the word “mother” that made Kindaichi peer more closely at her face. Mineko seemed to notice that and lowered her gaze, her ears reddening, but soon looked up again. The blush receded, and the quiet shadow wrapped itself around her more tightly.

“At the time, then, you were certain the body was your father’s?”

“Yes, I was,” Mineko said, nodding. “I believe it even now.”

Kindaichi narrowed his eyes at her in consternation. He started to say something, then had second thoughts, and said instead, “Were you alone at the time? Did no one else go with you?”

“My uncle and cousin were with me. And Mishima-san.”

“Did those people know your father well?”

“Yes, of course.”

“And did they also confirm that the body was your father’s?”

“They did.”

“So, after all of that,” Kindaichi said eventually, his brow furrowed, “why has this doubt about your father still being alive come out now?”

“Kindaichi-san!” Mineko’s voice grew suddenly emphatic. “I believed that body was my father’s, and I still believe it to this day. But, even without any decay, the shape of his face was so different from when he was alive. Maybe it was all of the anguish and misery he endured before his suicide, or the pain after he took the poison, but I remember in that instant someone whispering that he was like a different person. I even felt it myself. So, later, when people started pushing me, saying perhaps the body wasn’t my father’s, even though I am absolutely convinced that it was, I couldn’t help but feel shaken. And now, as his daughter, and the person who most closely examined his remains, when others see my uncertainty, of course they start to feel it, too. My uncle was so uncomfortable that he barely looked at Father’s face.”

Her tone grew dark again when she mentioned her uncle.

“Your uncle, that’s…?”

“My mother’s older brother. Toshihiko Shingu. He was also a viscount, before.”

“So, then, your cousin would be his child?”

“Yes, his only son.”

“I see. Now, did your father have any distinguishing marks on his body?”

“If he had, then there would have been no room for doubt.”

Kindaichi nodded and went on. “Yes, I can see that. But who is it that started bringing all this up in the first place? Saying that the corpse wasn’t your father’s?”

“My mother.” There was a coldness in her voice at this. It was so sharp, and so hard, that Kindaichi could not help the surprise showing on his face.

“Why would she do that?”

“Mother never believed that he killed himself. When we still had no idea if he was alive or dead, Mother never once thought it possible. She insisted that he was alive somewhere, in hiding. She seemed to be convinced he was dead for a time after his body was found, but before too long she stopped believing. She said we were all being fooled, and that the body wasn’t his. She even started saying that he had used someone as a body-double and was still in hiding.”

Kindaichi sat looking at her. Some unnameable emotion began to seethe deep in his gut, but he kept the unease to himself. “Surely, though, that’s just your mother’s love speaking?”

“No, no, not at all.” Mineko spoke as if the words tore at her throat. “My mother is afraid of him. Afraid that he is alive, and that he’ll come back someday to get his revenge…”

Kindaichi’s eyes narrowed in disbelief. She seemed to feel she had said too much. The blood drained from her face, but she did not turn away or avert her eyes. She stared straight at him, as if defying his unbelieving gaze. The shadowy flames wrapping around her billowed higher.

Since the question had touched on marital issues, Kindaichi would not ask any more unless Mineko offered more on her own. Naturally, she hesitated to do so.

Kindaichi decided to change the subject. “I understand that your father left no note behind. So, your mother must have—”

“No, actually, there was a note,” Mineko interrupted him.

Kindaichi was taken aback. “I’m sure that the newspapers all said there was no note!”

“It showed up much later. At the time, the fuss around my father’s disappearance had settled, so when I found it, I kept it within the family. We didn’t make it public out of worry it would set off more rumours and gossip.”

Mineko took an envelope out of her handbag and handed it to Kindaichi. He saw that the front read “To Mineko”, and the back “Hidesuke Tsubaki”. The characters were written in a clean, delicate hand. It was, of course, already open.

“Where was it hidden?”

“It was in the pages of one of my books. I had no idea about it. Last spring, I rearranged my shelves and moved unneeded books or ones that I’d already read into storage. Then, in summer, I went to air them out and check for insects, and it fell out.”

“May I read it?”

“Of course.”

The letter said:

Dear Mineko,

Please, do not hold this act against me. I can bear no more humiliation and disgrace. If this story comes to light, the good name of the Tsubaki family will be cast into the mud. Oh, the devil will indeed come and play his flute. I cannot bear to live to see that day come.

My Mineko, forgive me.

There was no signature.

“I suppose there is no doubt that this is your father’s handwriting?”

“None.”

“But what does he mean by this ‘humiliation and disgrace’ he says can’t bear? If he was talking about the loss of his title, then I can’t see how that that would reflect on his house, since it affects the entire class of peers.”

“No, that isn’t it…” Her tone was biting. “Father was indeed concerned about such things, but that’s not what he meant.”

“Then, what…?”

“Father… my father…” Sweat began to bead unpleasantly on Mineko’s forehead. Her breath grew heavy and fierce, as if she were possessed. “In spring, the police came and questioned my father as a suspect in the Tengindo murders.”

Kindaichi once more gripped the edge of the table in shock. It was like someone had hit him with a hammer. He gasped and cleared his throat, struggling to find something to say.

However, before he could, Mineko spoke on in a sharp, haunted tone.

“In truth, the photo composite that they kept revising and publishing in the newspapers looked exactly like my father. It was… unfortunate. However… That is not what drew the police’s attention to him. Someone sent them a letter tipping them off. I do not know who it was. But whoever it was, it is without a doubt someone in our household. Someone living at the estate, and within the Tsubaki, Shingu or Tamamushi families, I’m certain.”

In that instant, Mineko’s face appeared to Kindaichi like that of a terrible witch, and the dark shadow that lay across her seemed to burst into raging black flames.

CHAPTER 3

The Viscount’s Mysterious Trip

As a suspect in the Tengindo murders, Viscount Tsubaki had been put through intense, repeated interrogations by the police. That fact came as no surprise to Kosuke Kindaichi. But who would ever have dreamed that a member of the aristocracy would be marked a suspect in such a terrible case!

Kindaichi felt a heavy weight settle deep in his stomach like a ball of lead when he thought about the cruel fate of that class in such painful decline.

“Th-this…” Kindaichi swallowed loudly. “This is the first I’ve heard of it. I remember that case very well, but the newspapers never mentioned… that.”

“Yes, well, my father’s position was still such that we were able to keep it secret. He was taken in for questioning over and over, though. And as a suspect, he was also shown to the surviving Tengindo victims for identification. That wasn’t all. We in the family were also questioned about my father’s whereabouts on 15th January, the day of the Tengindo Incident,” said Mineko.

“I see, they wanted to check his alibi. But when was all of this?”

“Father’s first interrogation was on 20th February.”

“So, that would put it about ten days before his disappearance. Of course, you must have been able to prove his alibi right away?”

“Actually, no, we couldn’t. We had no idea where Father was or what he was doing on 15th January. We still don’t.”

Kindaichi gaped in shock at that. Mineko’s voice shook with emotion.

“I checked my diary entry for that day the moment the Tokyo police asked. I had written that Father had left on a trip to Ashi no Yu, a hot spring inn in Hakone, on 15th January. At the time he was working on a flute composition but had run into a block, so he said he was going to stay at Ashi no Yu for two or three days to work through it. He came home on the evening of the 17th, but of course we all just thought he had been exactly where he said. The police, though, said that they had contacted the inn and the staff found no record of his stay.”

She twisted her handkerchief in her hands. “From there, it seems that Father refused to talk any more about what he had been doing during that period. Which, of course, upset the police even further and for a time my father was in terrible trouble.”

“But in the end, they let him go, of course.”

“They did. Their suspicion began to approach certainty, which apparently frightened Father so much that he finally revealed where he had been on the 14th and the 15th. It seems they were able to confirm his alibi, but it took almost a whole week.”

“Where had your father been?!”

“I don’t know. He refused to tell anyone in the family.”

Kindaichi felt a flutter of nervous suspicion in his breast. What possible reason could a man have to hesitate in offering an alibi when under suspicion of a crime as serious as the Tengindo murders?

“Were there any special circumstances that would require such secrecy?”

“I simply can’t imagine what they could be,” Mineko said. Her voice was indignant. “Father was a frail-minded, or rather, a timid person. He was such a weak little man that even I found it irritating when I was a child. His only pleasure in life was playing the flute. I can’t imagine a man like that could ever have a secret that terrible. But most of all…” Mineko’s voice suddenly thickened with emotion. “From the middle of January, right around the time of that trip, he was acting… strangely.”

“Strangely how?”

“He seemed deeply distressed, and whenever anything out of the ordinary happened, he would get so frightened.”

“Frightened? Really?”

“Yes, but he’d been like that to some extent since the end of the war. I thought perhaps he had simply grown worse, but when I think about it now, it really was strange.”

“It seems to hint at something happening to disturb him around the new year. Do you have any idea what that might have been?”

“Not really, it’s just…”

“Just…? Just what?”

“Well, it’s just that great-uncle Tamamushi came to live at the estate at the end of last year.”

“Who is this great-uncle Tamamushi?”

“He’s my mother’s uncle, on her mother’s side. His name is Kimimaru Tamamushi. He was a count until this spring.”

“I see.” Kindaichi readied a memo pad and fountain pen on the table and looked back up at Mineko’s face. “You just said that whoever tipped off the police about your father must have lived at the estate. Why is that?”

“Because…” she began, before trailing off. The shadow wrapped around Mineko seemed once more to blaze up into pitch-black flames. “That’s what Father told me. I can remember it clearly even now. It was 26th February, the day after he came home from being cleared of those terrible suspicions. Even after the police accepted his innocence, everyone at home was still frightened around him, and no one but I would even come close. I was the only one who comforted him. That evening, Father was in his study on the first floor. The sun had gone down, but he had no lights on. He was just sitting in his chair, staring blankly into space. The sight of him, so lonely there, is still vivid in my mind. I could find no words to comfort him. I went to his knee, and all I could do was weep.”

Mineko’s face twisted strangely, and she seemed about to break into tears. She did not, though. Instead, she spoke on, her eyes wide, “Father stroked my hair, and said to me, ‘Mineko, there is a devil in this house. That is who wrote to the police about me.’ Those were his exact words.”

The shadow on her grew darker still. Kindaichi, though, was no longer surprised or confused by it. The secret to why she was shrouded in such darkness was becoming clearer by the moment.

“I was surprised, and looked up at him, asking him what he meant. He did not speak long, and his words were broken, hesitant. But basically, he said that the anonymous letter sent to the police included details about my father’s comings and goings around the time the Tengindo Incident occurred. It also had, in detail, things that he had said, things that only someone who lived with us could have known.”

Kindaichi felt a chill in his belly, as if something cold and clammy was crawling up his body from the floor. “Did your father say who it was?”

Mineko shook her head, her eyes shrouded.

“Was this simply something he suspected, or did he know clearly who had written the letter?”

“I think my father knew it clearly.”

“And what about you? Can you think of anyone would do such a cruel thing?”

Mineko’s lips twisted strangely. Her eyes flashed with anger.

“I am not certain. But, if you are looking for suspects, there are plenty I could offer. Starting with my mother…”

“Your mother?!”

Kindaichi gasped and stared at Mineko’s face. The creeping cold brought another unpleasant shiver. She simply stared back at him.

He took up his pen and said, “I see. Then, let me just confirm everyone who lives at the estate with you. There are three families, correct?”

“That’s right.”

“Let’s start with yours, then. So, your father was Tsubaki Hidesuke. How old was he?”

“Forty-three.”

“Who else is there?”

“My mother Akiko, forty. But…”

“But what?”

Her face tightened in irritation.

“If you end up meeting my mother, I imagine you’ll think I’m lying to you since she looks so young and beautiful. When she was very young, people said she was one of the most beautiful women in all the peerage, and even now she looks no older than thirty. For her, having a daughter as ugly as me must be unbearable. I wish it wasn’t so.”

Kindaichi looked at her, and started to speak, but immediately thought better of it. She did not seem the type to welcome empty compliments. He went on with his questions instead. “Then there is you. How old are you?”

“I am nineteen.”

“Do you have any brothers or sisters?”

“No, none.”

“Then it’s a family of three. Do you have a butler or other household staff?”

“We used to, but those days are all over. Oh, but there are still three other members of the household.”

“Who are they?”

“One is Shino. She is an old woman, maybe around sixty-two or sixty-three, who accompanied my mother from the Shingus when she married and has been with her for her whole life. She manages the household.”

“She must be a very strong person.”

“Yes, extremely. She still thinks of my mother as a child and refuses to refer to her as a lady now. She calls her ‘child’ or ‘young mistress’, and it seems to make my mother very happy.”

Kindaichi thought he heard a note of sarcasm behind the words but ignored it.

“And the other two?”

“One is Totaro Mishima. I’d say he’s about twenty-three or so. It seems that my father and his were friends in their school days. After he was discharged last autumn, he didn’t have anywhere to go, and Father took him in. He has become very valuable to the house.”

“Valuable in what way?”

Mineko blushed a bit, “Kindaichi-san, do you know how we survive now? We have to sell our things just to eat. But we don’t know anything about that kind of business. Dishonest merchants would take such advantage of us. But when Mishima-san started visiting us, all of that went much more smoothly. He is quite good at that sort of thing. That and procuring food. He grew to be so useful that Father asked him to come live with us.”

“He sounds admirable for such a young man, indeed. And the last one?”