Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

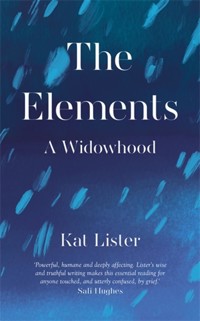

'Powerful, humane and deeply affecting, Lister's wise and truthful writing makes this essential reading for anyone touched, and utterly confused, by grief.' Sali Hughes 'The must-read memoir'Red What does it mean to become a widow at 35? In her mid-thirties Kat Lister lost her husband to brain cancer. After five years of being a wife and one of being a carer, in love and in and out of hospitals, she became a widow. In the year following his death Kat seeks refuge in stories of grief and widowhood, but struggles to find a language that can make sense of her experience and the physicality of bereavement. Instead, she turns to the elements - fire, water, earth, air - on her quest to come to terms with her grief, to inhabit her body again, and to find out who she is now. The Elements is a story of love, pain, hope and, ultimately, transformation.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 330

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

iii

The Elements

A Widowhood

Kat Lister

v

For Pat Longvi

vii

My life is not this steeply sloping hour

Through which you see me hasten on.

I am a tree standing before my background

I am but one of many of my mouths

The one that closes before all of them.

I am the rest between two notes

That harmonize only reluctantly:

For death wants to become the loudest tone—

But in the dark interval they reconcile

Tremblingly, and get along.

And the beauty of the song goes on.

— Rainer Maria Rilke, The Book of Hours, 1905 viii

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Have you ever watched a great cloud smudge like chalk into the faraway horizon? Wispy tails of precipitation that streak down and down towards the earth in vertical lines. A translucent curtain of dangling tentacles, each one evaporating from liquid to vapour before it even has time to reach solid ground.

Some call it the jellyfish of the skies.

I call it grief.

I last saw this meteorological curiosity in the spring of 2019, ten months after my husband died. I was standing on a rooftop car park in south-east London, looking out across the railway tracks, when my eyes were drawn to the dove-grey threads that marbled the sharp nib of the Shard in the distance, and for a brief moment I lost myself to these ghostly squiggles, these disintegrating fingertips, reflecting all the wraith-like movements I felt inside. There was something about this shapeshifting skyline that mirrored the nebulous outlines of my own widowhood, such as they were on that Saturday afternoon, dripping and blotting, curving and streaking, before evaporating into gas – a vanishing act that tricked the senses because it wasn’t disappearing at all, it was actually remaking itself from one state into another.

This car park epiphany wasn’t the first time I had stepped into nature in order to delve into my grief. When my life xiiupended in 2018, I reached outwards for the elements – fire, water, earth and air – because they helped me to understand the wild sensations I felt inside. The burning flames that needled across my skin and the implacable waves that crashed beneath it. The entwining roots that spread around my limbs and the bracing wind that whipped upwards and through me, tangling my hair.

These elements weren’t always easy to carry. In the early days of my grief, I would walk them around the perimeter of my local park, often in the rain, reassured by the gentle spots that pattered against the canopy of my umbrella. At night, I would stack up splinters of kindling inside my living room stove and watch a flickering of mustard and apricot pop and crackle into a blaze of enraged ruby flames.

In the astral light at 3am, during the first winter of my grief, it was the sound of the wind through the leaves of a silver birch tree in my garden that gave me comfort and reassurance as I struggled to sleep. Roots and branches. Cycles and movement. The rustling of a world outside my window. When my home became a time capsule to what had been lost, I often found myself wandering from room to room in the early hours of the morning, willing my husband to speak as I reached for his sweater and smothered my face into its bobbled sleeves.

I saw him everywhere. Amongst his battered John Le Carré books neatly arranged on the bookshelf. Between the cans of Guinness rammed at the back of our fridge. A toothbrush casually discarded by the sink. In his laundry – worn socks, treasured shirts, faded jeans – randomly intertwined with mine. xiiiA scattering of unremarkable objects that served to document the past like some kind of spectral crime scene: exhibits of a life shared and a life lost. Strewn buoys that ringed my drifting grief raft in this house we lived in, the house we loved, now a strange, unbearably quiet and dark expanse.

My story begins here, days after my husband died in his hospice bed – sleepwalking through the debris of cataclysmic loss. It was a foreign land occupied by shadows and past lives. A time when wakefulness finally succumbed to half-dreaming visions and invading memories. For it was during these nocturnal hours that my husband’s gentle presence seemed to unfurl. In this hypnagogic state, I was convinced that he had briefly returned to me, as if a celestial pathway could somehow reunite us between two disparate worlds. And maybe I was right, perhaps it could, albeit briefly. But magic is a transient illusion. All spells eventually break. Weeks turn to months, seasons evolve, the earth silently spins. I felt the oscillations rippling inside me, reverberations that signalled renewal. Grief cannot hold you here, they thrummed. But these sensations also betrayed the past, initiating a forwards and backwards motion that gradually pulled me away from the 35-year-old woman I recognised – the woman I had been.

I yearned for movement, I feared letting go. It was here, in this paradoxical moment, that death splintered me in two, creating dual identities, dancing and sparring, in darkness and light.

In the twelve months after my husband died of a glioblastoma brain tumour, many people asked me how it felt: to love, to grieve, to lose. Like a curious head poked through the xivshattered windshield of a concertinaed car wreck, this is akin to asking the slumped driver inside to point at a body part and show bystanders where it hurts. Pain is essential, it helps us identify our injuries and protect ourselves from any further harm, but it can also be difficult to quantify. There is no Richter scale for loss, no abacus that can calculate your daily progress as you hurtle from one extreme emotion to the next. There is simply no way to monitor your own heart’s rhythms when the one it was tied to stops beating.

I began writing in the winter of 2018 to confront the ugly facets of my grief, but I continued writing to try to co-opt them. It was the only way I could control what was happening inside me, the elemental changes that seemed to transform me from solid to liquid to gas, a transmutation that sometimes occurred in a single day as I went about my everyday tasks: wheeling a trolley through the supermarket aisle, rushing down an underground escalator to get to work, waiting in line at my local cafe to buy a takeaway coffee.

No one warned me about the power grief can wield over your subconscious, the way it ruthlessly inhabits and subverts you. In the immediate aftermath of my husband’s death, I struggled to locate him amid the debris; yet over time this quest ricocheted inward, a pursuit no longer focused on the absence around me, but the gaping chasm within. Perhaps that’s why I turned to widowed writers, scientific researchers and academic books to soothe the judgemental voice in my head that told me I was doing it wrong, grieving badly. I was looking for answers. I sought reassurance in the things I had never been told. xv

On a rainy afternoon, surrounded by medical books in London’s Wellcome Library, I uncovered tales of Native American women, widows of the Hopi Tribe in north-western Arizona, who have been known to experience spontaneous hallucinations of their dead husbands as a symptom of unresolved grief. I read stories of dolphins carrying their dead loved ones for days, refusing to eat or sleep, and elephants that returned, again and again, to the carcasses of their dead companions. I found strange comfort in the idea of ‘grieving geese’ who have been known to withdraw socially and lose weight after the loss of their mate.

Drowning in legal paperwork – bureaucratic obligations that seemed to homogenise and normalise his death – I took refuge in fairy stories as a way to escape. Faraway kingdoms that lassoed me away from reality. Enchanted spirit-lands inhabited by talking rivers, armless maidens and howling she-wolves. A beast that growls because he cannot speak. A frail white rose smeared with blood. Gothic prose that weaved wild worlds like vast spiders’ webs around me. I later recognised that these stories didn’t lasso me away from reality at all. Angela Carter once described fairy tales as ‘the science fiction of the past’. She called them ‘the land of bears and shooting stars’. Perhaps that’s why I dived into them so fervidly. When my life crossed over into make-believe, it was fantasy that recreated what I’d lost, feral allegories that brought me back to my love, and back to the shock. The more I read, the more I understood: these strange fables repeatedly sprung from death, the only narrative I could relate to as I filled out funeral paperwork in permanent black xviink. And so, I cast myself as the armless maiden who lay at the foot of a nursing bed. As the white rose smeared with blood. The she-wolf that howled as the morphine carried him away, light years away, to that far-off land of bears and shooting stars.

And yet, the real-life tale of the 35-year-old widow – the one who resides in south-east London? That was harder to find. I desperately searched for her amongst the bookshelves, a benevolent daemon that might be hiding in the spaces between words. She wasn’t there. Struggling to find a narrative that matched my crippling dysmorphia, I did the only thing I could: I wrote. When speech failed me, language danced frantically inside. Filling notepads and diaries, tapping into note apps, scribbling onto random serviettes and graffitiing across discarded envelopes, I narrated my own story. Scared of forgetting, I squirrelled away scraps of memories around my house, mysterious clues left by one version of myself for another to find. In the months that followed, I became a walking anachronism, mimicking everyday interactions as I internally conversed with the husband I had lost. Grief can split a person into multiple forms and sometimes they can communicate through time. In many ways, this book is a testament to this shapeshifting personality: wife and widow, witness and reporter. Who I was, and who I’m yet to be.

If the goal is to achieve some kind of profound transformation, then I suppose that grief turned me into a quester of sorts. My story seemed to correlate with the surreal bedtime tales that had captivated my imagination as a child: Alice through the looking-glass, Dorothy and her slippers, Lucy and xviia dusty wardrobe that leads into Narnia. Characters who journeyed to far-flung lands in order to capture something precious before finally returning home. My yellow brick road took me from the rugged peaks of Andalucía to the tempestuous waters of Mexico’s Pacific coast. As winter softened into spring, and my first complete year without the man I married passed, I wandered further into the outdoors, drawn to wild woods and kaleidoscopic skies. Meandering under towering elm trees and rustling leaves, I felt the ground beneath me, I found the words inside me – and, opening a blank notebook, I began to write.

My experience of widowhood might be unique to me, but considered in this context of far-flung lands, I hope that it has something universal to say about departure and return. The cryptic loop that brings us back to ourselves. Haven’t we all been thrown into the metaphorical woods at some point in our lives? Haven’t we all tried to retrieve something intangible beneath those elm trees – a displaced feeling, a failed relationship, a younger incarnation, even – despite everything we’ve seen and everything we know? Find me someone who hasn’t traipsed aimlessly over the past in order to find a reflection they recognise, a future to strive for, a narrative that fits. Are you still searching? So am I – and here’s my proof. Burn the maps. This is loss. A state of unbeing propelled by hope: a wild and radical feeling that can prevail, even in the depths of trauma and despair.

With this in mind, perhaps my story can be yours, too, because if my first year of mourning has taught me anything it’s that the elements are all around us. Sooner or later, if we xviiiopen ourselves up to possibility, we all have something to lose. And whilst I hope my story reaches out to any young widow who, like me, has desperately searched for herself amongst the bookshelves, I also want to speak to anyone who’s ever lost something significant in their lives. Something they believed in, something they took a chance on, something they loved. A loss so estranging, it harkens back to the word loss’s Germanic origins – to loosen, divide, cut apart.

Maybe death is the greatest disrupter of them all: a loss so extreme that any semblance of life after is forever shaped by it. That doesn’t mean the chances of reconfiguring yourself are any less possible. During my first year of widowhood, I watched my former life dissolve and effervesce, transforming from one substance to another and sometimes back again. Don’t let my published words fool you with their finality. We are all chemical reactions. The elements are within me, too. Even now, as I write this, I am transforming.

Into what, exactly? I’m still trying to figure that one out. Scientists call the physical process of post-trauma repair ‘wound healing’, but the miraculous regrowth is never quite the same. Scars remain in faithfulness to tell their story. Words have helped me to tell mine. Like clusters of incandescent stars, they led me out of the dark woods.

In the astral light at 3am, they kept me alive.

Part I

FIRE

Ashes denote that fire was;

Respect the grayest pile

For the departed creature’s sake

That hovered there awhile.

Fire exists the first in light,

And then consolidates,—

Only the chemist can disclose

Into what carbonates.

— Emily Dickinson, ‘Ashes denote that Fire was’, Poem 1063, c.1886–96 2

ONE

In a moment of anguish, perhaps madness, I licked the ashes from my fingertips and swallowed him down. He tasted of embers. Memories of childhood bonfire nights that danced on the tip of my tongue. The firm squeeze of my father’s hand as the crackle and hiss of a shooting firework surrendered to a bang-bang-bang of pyrotechnic stars. Flashes of brilliance that rocketed across the sky. An explosion, a jolt, then stillness. The taste of him brought me back here, back to the fire and the blast and the dust. Here, where sulphurous plumes permeated the air, enveloping me in the dark, my neck craned upwards, squinting for a horizon that had momentarily disappeared.

‘We view our memories as sacred,’ my husband wrote in 2017, meditating on the brain tumour that would take his life the following year. ‘They make up the autobiographical map that helps us navigate the present day.’ His words guided me on the day I scattered his ashes. On a crisp autumn morning in 2018, past and present blurred. Like the reassuring squeeze of my father’s hand when I was a child, glimmers of my husband’s sage wisdom helped me to complete my widowly duty on the banks of the River Thames. I reached into the wicker casket and dipped my palm inside, gently caressing him back and forth; once whole, now multitudinous, like millions of indistinguishable grains of sand. 4

He had asked to be scattered in Richmond-upon-Thames, at the bend of the river where we had picnicked on an early date in 2009. It was a characteristically romantic idea, but one that required a bit of practical planning to see it through. Questions needed to be asked, nautical information ascertained, which is what brought me to the water’s edge days after his death, standing bewildered on a Thames-side walkway discussing tide times with an apathetic boatman chewing gum. The rental would cost me £8 an hour, I was informed, as he scribbled his number on a scrap of paper. An arrangement was made, a time-slot decided. My mum picked us up in her Volkswagen Polo. What had originated as a romantic dying wish suddenly felt like a logistical test that I would either pass or fail to complete.

I placed the container of ashes in the backseat of the car, strapped myself into the seat beside them and listened to the mellow burble of Radio 4 as we drove. When I closed my eyes and tried to remember our picnic a decade earlier, something stirred. The sensation of damp grass between my toes. The touch of his fingers as they traced their way across the nape of my neck. Limbs and eyes and mouths on skin.

Anticipation.

I wasn’t expecting to see him that day. Our first date had occurred the previous evening, involving a priceless incident with a shot of black pepper vodka. I had brought him to my favourite Polish restaurant in Shepherd’s Bush. I watched him – half-enthusiastically, half-trepidatiously – plunge his fork into a plate of pickled herring and sauerkraut, and, between slurps of 5beetroot soup, I chronicled my mother’s arduous journey from Gdańsk to London in the late 1950s. He listened attentively, leaning in to butterfly-catch every word. He always listened this way and sometimes, when he replied, I heard cosmic symphonies.

You can’t always pinpoint a feeling, but I’m pretty sure our opening sonata began that evening over a midnight plate of plum pierogi on Goldhawk Road. Against the soft patter of April showers, he began to unfurl, a sequence of movements that opened numerous doors to spectacular worlds. Arvo Pärt’s Cantus in Memoriam Benjamin Britten. The dusky tones of the British Post-Impressionist Walter Sickert. Our shared appreciation of Larry David. The unparalleled brilliance of all-you-can-eat dim sum. Then – wham! – the table between us shook. Interrupted by a cajoling babcia who had slammed her extensive vodka menu down, the conversation immediately diverted to neat liquor, but which one? His index finger zigzagged down the list of flavours – plum, cherry, honey, bison grass – until it lingered at a danger zone marked pepper, his one eyebrow raised.

‘Don’t go there,’ I warned.

‘Why not?’ he asked.

‘I just wouldn’t.’

‘You wouldn’t?’

He did. Twelve hours later, I was walking home from the supermarket when my mobile pinged. He’d made it out the other side, he quipped, and this weather was too good to miss.

‘Meet me in Richmond?’ 6

On a sunny September morning, a decade after we lay tipsy and outstretched on the riverbed grass, my best friend Andy rowed a boat out whilst I cradled my husband tightly between my knees. With every rock of the skiff, I held on tighter to the casket, marvelling at the weight of him, the density he had left behind. No one had warned me about this, I thought to myself, as the boat’s oars skimmed the water. This gravitational pull, the earthy tangibility of death. With every handful I released, he rippled and swirled. I watched him swell and billow beneath the surface. Microscopic clusters of phosphates and minerals that danced and dispersed like sparkling stardust trails.

That’s the thing about ashes. They linger amongst us, just like sulphurous plumes and evocative childhood memories, finding lifelines you never knew existed. Quite literally, in my case. As I sprinkled him onto the water, powdered flecks of him carried away with the breeze, dispersing through my hair and settling on my skin. They clung to the bodily tributaries that forked across the palms of my hands, finding a way into the contours and creases. Using the sleeve of my T-shirt, I wiped away the pepper-pot dust that coated the screen of my iPhone. And when I reached inside the top pocket of my dungarees for a scrap of tissue, I found him there too. Perhaps this explains my visceral urge to taste the ashes that day. In the chasm of grief, this was no longer a rational world. Standing in a pub toilet with his remnants under my fingernails, anguish turned to horror. Where should they go? From fingertips to mouth, a primal voice replied. Then I turned on the basin taps and watched the rest of him drain away. 7

In order to understand the woman who licked her ashen fingers like they were sherbet straws, we need to go back, right back, to when the tectonic plates shifted. Nine years ago, on a Sunday evening in 2012, my life changed irreparably. Roughly a week after my husband’s 35th birthday, a year before we married, he blacked out on his kitchen floor waiting for the kettle to boil. We were living in separate ends of London at the time, so when he called me at 10pm to tell me that he’d woken with bruises scattered down one side of his face and torso, that he was going to run a bath, and that he really didn’t think a hospital dash would be necessary, I urged him to call a taxi. True to form, he said he absolutely would and jumped on the bus. A rudimentary CT scan in an east London Accident & Emergency department revealed that for the length of our three-year relationship, a tumour had been steadily growing in the right side of his brain. It was the size of a lemon, we were later told, and a neurosurgeon would need to operate immediately in order to diagnose its type and grade.

It’s hard to do it, even now. Stand on the charred ground and look down. I’m giving it a go for the sake of the story, but I’m not sure that it’s possible to rake over the past and examine what happened without neatening it a little, or smoothing over the rough surface in some way. I can squish the main details into a couple of paragraphs, but it doesn’t give you the messy bits I have tried to block out, and it is the messy bits that I need to confront. The misshapen parts that I’m tempted to kick away because they complicate the narrative and expose the flaws. Or maybe they expose my flaws, maybe it’s that. The truth is 8that my naivety on that night still haunts me because I couldn’t foresee it – the brain tumour – and a part of me still believes that if I had, it might not have happened at all. Which sounds implausible but, then again, so is what happened next.

Between his midnight bus trip and the 2am CT scan on a busy A&E ward, I fell asleep at home waiting for news. I was convinced that he had simply sleepwalked during an afternoon nap and walked into his bookshelf. He did that fairly regularly. He also dropped his keys a lot – so much so that I ribbed him for it. It wasn’t until I woke up at 7.30am that I saw a voicemail on my iPhone screen and listened to his three-minute message telling me that they had found a large mass in his brain and that he had been admitted for further tests. I placed the mobile phone carefully on my bedside table and, kneeling on my bed, smacked my hand repeatedly against my forehead – rapid, sharp blows that came at me again and again, as if my arm belonged to someone else entirely. Even now, I can feel the slaps, the burning sensation it left on my skin, a primal attempt to jolt me out of what was happening, and an ineffectual one, because all it left me with was the present. A fire that was raging between my temples.

Memory can be a unreliable resource, especially in times of trauma, but I can recall the afternoon we were first introduced to the words ‘glioblastoma multiforme’ with the same precision as the grocery list I scribbled down on a Post-It note this morning. I can still see my husband reaching into a trouser pocket for his mobile and Googling the words as we waited for a copy of his scans in a consulting room at Homerton 9University Hospital. I can picture his face as he swiped through the Wikipedia page whilst I pleaded with him to stop. I can hear the loud whoosh of the automatic sliding doors as we left in silence. I can remember the cold blast of air and the smack of heavy rain on the tarmac outside the main entrance. And I can feel my legs buckling underneath me, followed by the dull sensation of knees hitting concrete as I concertinaed to the floor. It was only when my husband hoisted me back to my feet that I realised that the loud wails I could hear across the car park were actually my own.

A steroid was prescribed, dexamethasone, to reduce the swelling. This wasn’t a treatment, we were informed, but a way to manage symptoms, prevent further seizures, mellow that crude sound tumour with a soft pedal approach. But the hammer mechanism kept doggedly on, and the pills made him hyperactive and awake. I pounded the pavements to work each morning in an absent daze. My husband attended a brain exhibition in central London. Devouring a plate of fish and chips later that evening, he told me about a Bronze Age skull he’d discovered in the cutting section, drilled with four burr holes.

I avoided the fruit aisle in our local supermarket.

He emailed me citrus jokes.

The lemon-sized tumour kept growing.

Weeks later, he was urgently wheeled into a basement operating room at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London. As he lay on the operating table, I was packing boxes and moving us into our first home together: bubble-wrapping crockery, ornaments and glassware as his 10neurosurgeon resected, welded and stitched for twelve straight hours across the other side of town. In the early hours of the evening, I sat on a plastic seat outside his recovery room and waited for news as the hot drinks vending machine vibrated and whirred from the other end of the corridor. There was a faint smell of citrus in the air, or maybe it was just the hospital disinfectant spray, but when my husband called out my name, the delirium was instantly quelled. The bulk tumour had been excised, we were told. His mother and I watched him take exhilarated sips of milky tea through a straw and I stroked his hand as he proclaimed that this was the best cup of tea he had ever tasted. Somewhere between those slurps we stepped over the borderline between our past and future lives without even realising it, a shift so imperceptible that it was lost in the euphoria of his widening smile, in this diaphanous moment between recovery bays. When the results of his biopsy came through a week later we were told that they’d removed a Grade 2 oligoastrocytoma, a ‘mixed glioma’ tumour that is made up of a variety of different glial cells that makes its behaviour difficult to predict. In layman’s terms, it was complicated, and this diagnosis would never be a stable one – but for now, at least, his condition was under control.

Emily Dickinson once described hope as a ‘strange invention’. I think I understand what she meant. The idea that hope is something that is imagined and willed and constructed into existence. I welded the clunky parts – the confusing scans, the lengthy hospital appointments, the Let’s not go there just yet evasive replies – and I fused them together with the heat of my 11own ignorance. I softened them and sculpted them without ever asking his doctors the one question that pulsed through me day after day: But when will he die? Although I was unaware of it at the time, my husband’s diagnosis marked a point where I began to construct stories in order to avoid what was happening. The frightening reality that our lives were now moulded around a tumour that I couldn’t see nor fully understand. On the morning of my husband’s first appointment at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery, he dressed in a suit and tie, carefully writing down notes in a writing pad, and when his neurosurgeon circled his capped biro around the globular white-and-grey mass that had invaded the right-hand side of his brain, I burst into tears. The neurosurgeon looked at me, surprised.

‘But I thought you knew it was a brain tumour?’ he asked as he handed me a tissue.

From this morning forward, something in me changed, or maybe I split in two. The hopeful me versus the fearful me. This diagnosis could never be a fixed state – I knew this, I think I always did, but I allowed myself to believe in spite of what I knew to be true. Although at least 70 per cent of the tumour could be removed, the remaining glioma, that 30 per cent, would always be inoperable and it could always mutate. I had faith in the unforeseeable, but the horror had embedded itself and would remain. As time passed, I would often joke amongst friends that the remaining 30 per cent of resected tumour was like a third person in our marriage, and sometimes making that mischievous Princess Diana head tilt 12gave me a sense of control. At other times, this felt like a bit part that I played for a baffled audience. A desperate attempt to armour the translucent woman who smelled citrus groves in hospital corridors and drafted eulogies in her head as she waited for the bus.

Over the next six years, we lived with a shapeshifting tumour that, for months at a time, responded well to treatment, before viciously mutating in ways even pioneering doctors found difficult to predict. Over time, volatility became our normal and I weathered the unpredictability: that lurch, deep inside, every time I saw his body hit the floor with another grand mal seizure that signalled yet more tumour growth. Despite regular 999 calls, and midnight dashes to A&E, I found a pathway through each crisis with the help of my husband’s sparkling wit and his gracious heart. I clung on to the contours of his optimism and imagination, as though it were a magical rescue harness. Until the tumour stopped responding to the radiotherapy, the chemotherapy, the experimental drug trialling. And, just like that, my harness snapped.

In the late summer of 2018, I sat by my husband’s bedside at King’s College Hospital and calmly repeated what his oncologist had told me hours earlier. His brain cancer had aggressively developed past the point of further treatment, surrendering him to a cruel, coarse reality – a place that science couldn’t reach. He had been given weeks to live. Even now, my mind wanders back to the hospice room into which he was eventually moved. Me frantically fetching laundry each morning; him sitting heroically in his wheelchair, willing himself to resist, to 13survive, to live. He willed himself, fearlessly, for six excruciating weeks. He was only 41 years old.

In the weeks that followed my husband’s death, I think there was a small part of me that expected nihility, obliteration, a big bang followed by nothingness. There was a presumption, inspired by all the art and literature that I had consumed over the years, that my heart would simply stop beating, that the shock would fell me before I had even ordered his cremation certificate and arranged the funeral service. It’s the ultimate tragedy, isn’t it? A love cut short. I am reluctant to mention the most famous star-crossed lovers, Romeo and Juliet, because they seem a far too obvious, dare I say clichéd, choice, but this was the first play I read at school, and it had an impact on how I viewed love and grief. Literature teaches us that there is romance in death. It gives us, the reader, a clear and unambiguous ending. Juliet isn’t the only female protagonist whose grief and trauma lead her to an extreme self-sacrificing deed. Anna Karenina throws herself onto the railway tracks and into the path of a speeding train. Madame Bovary opens a jar of arsenic. Come to think of it, most of the literature I read in my impressionable teenage years was formed by the imaginations of men, and so my understanding of grief was shaped by them, too. An image of a woman on fire, a wheel of explosive powder sparking as she spins, so consumed by her losses, and by her luckless fate, that she burns herself out, quite spectacularly, in a brilliant blaze.

In reality, grief – much like life, and love, and death – is a far more nuanced and confusing state of play. It weighs you 14down and drags you around. Weeks stretch inside a shapeless void where the only certainties you’re faced with every day are absence and existence. His and yours. Grief is neither a romantic, opium-fuelled Coleridge poem, nor a beautiful and stylised Millais painting. It is messy and rough; it is unforgiving and cruel. An encompassing pressure that made my head feel pushed and squeezed, compressing my everyday thoughts as though I were permanently clamped in a vice.

If you were to ask me what acute loss feels like, I’d motion you to the pub toilet in which I tasted my husband’s ashes, ten minutes after I’d ordered a club sandwich for lunch with an empty casket lodged between my feet. If grief resides anywhere, it’s here – a juncture where memories pinball the walls and a surreal delirium takes over the brain, yet somehow life around you carries on. Minutes after I watched the grains of my former life disappear down the plughole, I wiped the dust from my cheeks, shook down both dungaree legs, pulled up my socks, and rejoined my mum and best friend at the lunch table outside. The deed had been done, leaving a smoky oesophageal trail that permeated my body, leaching out through my pores. I swished it down with gulps of ginger beer and reached for another bite of my sandwich, telling neither of my fellow diners what I had just done.

I first felt this stealthy derangement 24 hours after I received The Call in the early hours of the morning – the call that told me my husband had died in his hospice bed whilst I slept restlessly at home. On a drab Saturday morning I sat silently in a third-floor visitor room, a few feet away from where he had 15taken his final breaths, and absently scanned the bookshelf in front of me. Row upon row of novels that might be flicked through in a traumatised daze, but never really read in the way that books should. Like the tepid mug of tea that was brought to me as I waited to collect my husband’s belongings, everything here seemed unexceptionally normal and therefore obscenely wrong. An innocuous room filled with unremarkable things, I thought. A desperate place where hope dwindles between the shelves.

When I finally brought it all home – his rucksack, a death certificate and three plastic carrier bags filled with his possessions – I lined it up in our kitchen like groceries left to unpack. Opening and emptying, I grouped his things in neat categories on the floor, methodically logging every item like some kind of grief administrator. The mundanity of everyday life, I thought to myself as I surveyed the flotsam. An extraordinary man reduced to these piles of ordinary things. Unopened packets of biscuits, bags of crisps, a half-used bottle of shower gel, a box of uneaten chocolates. Jogging bottoms, sweaty t-shirts, a couple of battered magazines. Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time. A laptop. One iPad. His notepads – one, two, three, four of them – the ones he stacked in a Jenga-style tower next to his pillow whilst he slept.

He was halfway through writing a memoir exploring memory and consciousness when his brain tumour advanced and, like so many hospital inpatients, his nursing bed quickly became his world. A tiny nook where he could reclaim some semblance of normalcy, order and control. As a day-visiting wife, I quickly learned not to rearrange his belongings, realising that 16each item signified something in this borderland between life and death. Crammed into hospice carrier bags, that meaning now seemed permanently lost, but I still grasped at them anyway: a tired, listless attempt to recover any remnants that I could. I carefully fished out his headphones, wrapped the cable in neat loops around the headband, and placed them inside his office desk drawer. There was an upsetting correlation between the unopened packet of biscuits and the notepad that trailed off into nothingness on page five, and as I excavated more and more, the act of retrieval, this perverted lucky dip, led me to his dressing gown at the bottom of the plastic. I placed my head between the handles, shut my eyes, and closed the bag tightly around me, breathing him in, breathing him out, whilst crude memories span and whirled.

The smell brought me back to those first days in the summer of 2018, on a bustling ward at King’s College Hospital, waiting for news from his oncologist five miles away at UCH Macmillan Cancer Centre. After years of drawn-out tests and treatments, what-ifs and maybes, his deterioration and subsequent hospital admission happened at breakneck speed, within a matter of days. One moment he was complaining of a tremor, and the next I was cutting up his sausage and mash into bitesize chunks, aeroplaning him mouthfuls of food, wondering at what point I should dial 999 to ask for help. What constitutes an emergency? I thought to myself. What makes a tragedy? Had it already occurred last week when I heard a thump and a yelp from our bedroom and rushed down, two steps at a time, to find him splayed on the floor? Was it here in our kitchen, right now? Had I already17witnessed it unfold in front of me, watching him turn on the taps and absent-mindedly saunter away from the washing up, leaving the water dangerously close to overflowing onto the floor?

I made the call that evening and waited for the flashing blue lights to twinkle outside, a silent alarm on a Friday night that was watched by a sloshed queue of revellers in the fish and chip shop over the road. The doctors in A&E couldn’t be 100 per cent certain, but it was probable that his uncontrollable tremors and facial drooping indicated disease progression, which would explain the minor stroke that had probably occurred days, maybe weeks, before.

After years of steady uncertainty, the pedal was pushed, the throttle valve opened. At the point where we began discussing hospice waiting lists, I sat cross-legged on a sweaty mattress staring blankly at a blood pressure monitor trolley whilst my husband meticulously took me through all the things I would need to know when the time came. Building society log-ins, email passwords, insurance numbers, updated funeral wishes. A list of people – colleagues from work, friends from university, ex-girlfriends, distant relatives – who I would need to update each day with snippets of his worsening condition, highly edited, so as not to incite panic.

Despite his tremors, he still managed to grip his biro and shakily write down a list. I babbled about the book I was currently reading, loosely parroting highlighted sections of prose in order to drown out the gentle moans of the elderly patient next door. In times of struggle, these were the roles we steadfastly assumed for ourselves. Whereas I retreated into my subliminal 18self, he reached out into the world for facts and information as a way to control the things that frightened him. But now, on the edge of the precipice, this dualism between his realism and my imagination seemed at odds with what was happening.