Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Old Pond Books

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

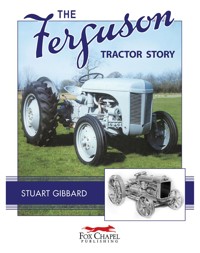

The little grey Fergie is Britain's best-loved tractor, the light user-friendly machine that finally replaced the horse on farms. This highly illustrated account covers the full history of Harry Ferguson's tractor products from his pioneering work before the 1930s to the merger with Massey in 1957. The author has had access to fresh archive material and has interviewed many of the surviving men who were associated with Ferguson. The appeal of the Fergie lay in its lightness and utility, and also in the system of mechanized farming of which it was a part. Throughout the book, reference is made to the implements which lay at the heart of the system. Stuart Gibbard has won "Tractor and Machinery" magazine's award for the best British tractor book five years running.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 244

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

‘Beauty in engineering is that which is simple, has no superfluous parts and serves exactly the purpose.’

HARRY FERGUSON

The Ferguson Tractor Story

Old Pond Publishing is an imprint of Fox Chapel Publishers International Ltd.

Copyright © 2000, 2020 by Stuart Gibbard and Fox Chapel Publishers International Ltd.

The moral right of the author in this work has been asserted.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission of Fox Chapel Publishers, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in an acknowledged review.

ISBN 978-1-912158-44-7 (paperback)978-1-913618-06-3 (ebook)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Fox Chapel Publishing, 903 Square Street, Mount Joy, PA 17552, U.S.A.

Fox Chapel Publishers International Ltd., 7 Danefield Road, Selsey (Chichester), West Sussex PO20 9DA, U.K.

www.oldpond.com

Frontispiece illustration: One of hundreds of thousands of Ferguson tractors still working worldwide, this TE-20 is used for launching fishing boats on the Norfolk coast.

Contents

Acknowledgements

Author’s Note

Preface

Foreword

Introduction

The Ferguson System

Chapter One

The Belfast Plough

Chapter Two

The Ferguson-Brown

Chapter Three

The Ford Ferguson

Chapter Four

The TE-20 Family

Chapter Five

Ferguson Overseas

Chapter Six

Massey-Harris-Ferguson

Epilogue

The Ferguson Legacy

Appendix 1

Ferguson Conversions

Appendix 2

Ferguson Tractor Serial Numbers and Designations

Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgements

The greatest enjoyment that comes from writing a book is not, as many will think, from seeing your name on the cover and your words in print. That is a novelty that quickly passes. No, for me, the real pleasure is in the research and the opportunities it brings - in particular, the opportunity to talk to the people who were in at the deep end. There is no greater privilege than being given the chance to meet, talk to and learn from the men who designed, built, demonstrated and sold the tractors. It is a pleasure that still remains undiminished after many books.

Each book is different, as is each company, but the warm welcome, considerable assistance and encouragement that I receive from the people who patiently and knowledgeably answer my questions remain the same, and the Ferguson men were no exception.

These were the people who brought the story alive, not me. It was difficult not to be moved by their pioneering spirit and the inspiration that pervaded their conversation, or be swept up by the emotion of the triumphs and tribulations as the events were recounted as if they were yesterday. I often realise what a task I set those willing few when I expected them to remember every detail of something that happened more than sixty years ago when I can’t even remember where I put my pencil ten minutes ago.

There was, however, one difference between the Ferguson men and people I have interviewed from other organisations. I am always aware of an overwhelming sense of loyalty to the product or company, even if that concern has long since disappeared. But here the loyalty seemed almost tangibly greater, and much of it reserved for the one individual who had obviously had a strong influence on their lives. That man of course was Harry Ferguson.

There are many ex-Ferguson personnel to be acknowledged, and sadly several of those who helped with the book are no longer with us. They include Alex Patterson, who was not in the best of health when I interviewed him, but his mind was as sharp as ever and his attention to detail was unsurpassed.

Alex’s help was invaluable and there were few questions that he could not answer, having joined Harry Ferguson in 1938, and becoming superintendent of engineering during the TE-20 era. He also kindly read my manuscript and filled in any missing information.

There were many other ex-Ferguson men who kindly made time for me, were at the end of a telephone, invited me into their homes or met me over a pint to share their wonderful reminiscences. They included: Jack Bibby, Dick Dowdeswell, Bill Halford, Roy Harriman, Nigel Liney, Nibby Newbold, John Roberts, Colin Steventon and Bud White. To this list, I must add Jim Wallace.

Special thanks were due to the late Erik Fredriksen. Erik traced most of my contacts and set up the meetings with many of the above gentlemen. He kindly gave up three days of his time to accompany me (I could say navigate me, but he continually got me lost) around the Coventry area on my visits and steer me around what few archives remained at Banner Lane at the time. He helped me with a great deal of information, and for anybody wishing to learn more about the ‘big Fergie’, I can heartily recommend trying to find a copy of his little booklet, The Legendary LTX Tractor.

I must pay special tribute to another ex-Ferguson man and writer, the late Colin Fraser, who I had the opportunity to meet during the course of my research. Colin’s biography, Harry Ferguson - Inventor & Pioneer, remains the benchmark Ferguson history and is every Ferguson enthusiast’s bible. It is impossible to write about Ferguson without first delving into this important reference work.

At the time of my original research, Banner Lane was still in operation and was still regarded as home to the Massey Ferguson tractor, but all that has now gone with the closure of the plant in 2002. Massey Ferguson has been part of AGCO since 1994, and many of the personnel from that organisation, as well as its Coventry plant, kindly assisted in the preparation of this book. I would like to make particular mention of Jim Newbold and Ted Everett from the photographic library.

Although John Briscoe was not directly involved in this book, he was a useful contact to me over all the years since I began writing. Thanks to him, I had already amassed a certain amount of information and photographs on Ferguson tractors before I even started this project. He often suggested that I should turn my attentions to grey or red/grey tractors rather than waste my time on other manufacturers while he patiently sourced photographs for my other books or articles. Ironically, by the time this Ferguson book was planned, he had retired from AGCO.

Ferguson tractors and equipment have a following like no other make, and the Ferguson enthusiasts and collectors who worship the grey are a learned and dedicated band, always willing to share their extensive knowledge of the marque. Sadly, Selwyn Houghton and Ben Serjeant are no longer with us. Selwyn’s understanding of Ferguson-Brown tractors was unmatched, and Ben started researching Ferguson history before anyone else and inspired me to follow his lead.

Three individuals in particular gave me unrivalled assistance, loaned valuable documentation and photographs, and allowed me access to their own research. They were: Mike Thorne, a true enthusiast who provided all the right contacts; Ian Halstead, who always said that I should write a Ferguson book; and Jim Russell, whose Ferguson knowledge is eclipsed only by his photographic skill. Thank you gentlemen, it was most appreciated, and I know your shared interest in the marque remains undiminished.

I must also thank Jim Russell and his, wife, Jane, for kindly providing me with (quality) accommodation and food during my time at Coventry, even if Jim did get his own back by keeping me up until after midnight with Ferguson bedtime stories. I am equally grateful to the many Ferguson enthusiasts who helped, provided information or photographs or allowed their tractors to be photographed at the time. Amongst their number were Noel Collen, David Lory, Tom Lowther, John Moffitt, John Popplewell and Robin Price.

I am aware that in the 20 years that have passed since this book was originally published in 2000, many of those who assisted me are no longer alive, or will have retired from the positions they held at that time (as given in parentheses). However, all are equally deserving of full acknowledgement, and include: Martin Cole, Mark Farmer, John Farnworth, John Foxwell, Phil Homer (Standard Motor Club), Sandra Nichols (Ford Motor Company), Stephen Perry (Perkins Engines), Derek Sansom (DSA), Clive Scattergood (Perkins Engines), Robin Shackleton (Hydro Agri), Bonnie Walworth (Ford Motor Company) and David Woods (New Holland).

Finally, the first edition of The Ferguson Tractor Story would not have been possible without the wonderful team at the original Old Pond organisation: editor, Julanne Arnold; designer, Liz Watling; and my good friend and publisher, Roger Smith (who also took several excellent photographs for the book). Thanks are also due to the team at Fox Chapel for this new edition. As with all my books and articles, I must also thank my long-suffering wife, Sue, who reads everything I write and adds her own constructive comments.

Author’s Note

It is always a dilemma for an author of an historical book whether to use imperial or metric measurements. I was brought up with imperial units, but was forced into metrication during my teenage years. Being a traditionalist, I tend to favour the former.

The method I have tended to adopt for my other books is to use the system most in keeping with the period that I am writing about, and the era of the Ferguson remains firmly in imperial times. Having said that, however, most UK motor manufacturers preferred to quote engine capacities in cubic centimetres, while manufacturers in the USA used cubic inches. It seemed only right to do the same while giving the alternative figures in parentheses. Therefore, the sizes of the North American engines are given in cubic inches first followed by the metric equivalent in brackets and vice versa for the European power units.

The Standard Motor Company also tended to refer to its engines by their bore sizes in millimetres; for example, the 80 mm engine or the 85 mm engine. It would be illogical to present these any differently.

Several different systems for calculating or measuring engine power have been used over the years. Those figures that I can verify as true brake horsepower (bhp) are given as such, while others may be rated, drawbar or pto horsepower.

Preface

Writing a book about a machine as famous as the Ferguson tractor is a daunting proposition. Few tractors have captured the imagination as much as the ‘little grey Fergie’. I can think of no other agricultural machine that has won such universal acclaim or been so fondly remembered. For many farmers, particularly those with smaller or more remote holdings, it was their first true taste of mechanised farming, and most people who have lived or worked in the country will have had some experience or knowledge of the Ferguson tractor.

The TE-20 has become an icon of Britain’s engineering heritage of the twentieth century, as legendary as Sir Nigel Gresley’s Pacific railway locomotives or Sir Alec Issigonis’s Mini car. To the layman, the Ferguson is the classic tractor personified, and it still remains the first choice for many smallholders, ‘weekend’ farmers or the Pony Club fraternity with a small paddock to mow.

Dare I say that having been brought up on an all-Ford farm, with just one solitary TE-20 that was used as a yard tractor and for spraying duties, I was brainwashed into believing that the praise heaped on the Ferguson was no more than just hype? We knew our Fordson Diesel Major tractors were more powerful and believed them to be superior, even if they lacked draft control hydraulics. A friend of mine once disparagingly remarked that the ‘Fergie’ was only really suitable for the man who had one acre and a goat. Had he got a valid point or was he being unfair to the Ferguson tractor?

An ex-Ferguson training instructor once admitted to me that the tractor was possibly the weak link in the Ferguson System and had its limitations in terms of size and power. When towing from the drawbar, he said, ‘It wouldn’t pull the skin off a rice pudding.’ His words, not mine.

The author was introduced to the Ferguson System at a young age. This TE-20 model was the sole Ferguson among a fleet of Fordson tractors on his family farm.

However, he qualified this by saying that when full use was made of its hydraulic system with the correct implements, the Ferguson tractor was transformed, as if by magic, into an unbeatable machine that would run rings around the opposition. Here indeed was beauty in engineering.

It must not be forgotten that the Ferguson tractor brought affordable and practical mechanisation to the less-favoured areas and opened up the marginal land of many developing countries, or that it could till or plough hillside and stony land and inaccessible fields where no other machines could go. It brought motive power to upland and lowland farmers, market gardeners, hop, wine and fruit growers, local councils and municipal corporations the world over. Over one million Ferguson tractors were sold between 1936 and 1957, and over one million people cannot be that wrong.

I came to this story with an open mind, willing to be persuaded that the Ferguson tractor was or was not the stuff that legends are made of. No doubt, I have been more than a little influenced by the many ex-Ferguson men I have spoken to, and perhaps subconsciously affected by the magnetism of Harry Ferguson’s words and philosophy that are the very fabric of every piece of Ferguson literature I have read. I was also greatly impressed by just how much more could have been achieved had the LTX prototype been allowed to go into production, and have finished this book a firm advocate of the Ferguson tractor.

Having said that, I have not embellished or glorified the story and have presented the trials, tribulations and mistakes as well as the triumphs, successes and achievements. I have left it up to the readers to make their own minds up as to whether the Ferguson tractor really was the machine that revolutionised farming.

I have also tried to give both sides of the story of Harry Ferguson’s successive partnerships that were formed on the road to realising his dream to build the tractor that finally replaced the horse. That vision is an inseparable part of the story and I felt I could not consider the tractor without looking at Ferguson, the man, and the greater concept of his complete farming system. This is not the first book to be written on Ferguson, nor will it be the last, but I hope it provides a further insight into the machine that became affectionately known as the ‘little grey Fergie’.

STUART GIBBARD

January 2020

Foreword

By the late Alex Patterson, Engineering Workshop Manager,Harry Ferguson Ltd. and Massey Ferguson, 1945-1967.

My association with Harry Ferguson began in Belfast in 1938 when I joined his company as an apprentice. Little did I realise at the time that I would, in one way or the other, be connected with farm machinery and in particular with Massey Ferguson for the rest of my working life.

I always felt privileged to be part of the development of the Ferguson System and appreciated the importance of Mr. Ferguson’s vision. In its most basic form this was a drive to improve the lot of the ordinary farmer in his quest to feed his family and indeed, on a grander scale, to help feed the world.

Harry Ferguson gave me the opportunity to contribute to the development of his farm machinery system and I learned so much from him. His key thoughts – simplicity of design and sound engineering principles – were always applied to his manufacturing and development philosophies. My association with Mr. Ferguson continued many years after he had severed his links with Massey Ferguson; we corresponded until the time of his death and I treasure his letters to this day.

Over the years I have been asked to contribute to many publications and documentaries regarding Harry Ferguson and I am more than happy to say that Stuart Gibbard’s book is one of the most thoroughly researched and accurate accounts I have read.

ALEX PATTERSON

August 2000

INTRODUCTION

The Ferguson System

‘The machine that revolutionised farming’ is a remarkable accolade, and one that has been applied many times to the Ferguson tractor. It is obviously a contentious statement as other machines, such as the combine harvester, have had an equal, if not arguably greater, impact on agriculture. But the importance of the Ferguson’s contribution to the progress of mechanisation cannot be denied, and its principles are embodied in the design of almost every modern tractor or mounted implement. Its inventor Harry Ferguson claimed, ‘The Ferguson System is an entirely new way of farming, born of a revolution in agricultural engineering and production methods’.

But what exactly was the Ferguson System? Most people are aware that the Ferguson tractor was famous for its hydraulic lift. It was not the first or only tractor of the time to have a power lift, but while other manufacturers did eventually develop their own basic hydraulic systems, none were as refined or as advanced as the Ferguson. What Harry Ferguson pioneered was a system of hydraulic depth control and an effective three-point linkage arrangement that allowed the tractor and implement to work together as one integrated unit. Although these are features we take for granted today as they have been adopted in some form by most of the world’s major tractor manufacturers, we still need to consider the principles and benefits of the system to fully understand the development of the Ferguson tractor.

The agricultural tractors that first appeared on farms during the early years of the twentieth century were thought of as no more than towing vehicles to replace draught animals. They worked with adapted horse equipment that was trailed behind the tractor by a drawbar-hitch, pole or simply a length of chain. It was a very inadequate arrangement; the combination of the tractor and trailed implement made a cumbersome unit that could not be reversed into tight corners and needed a large headland for turning. Work-rates were not improved by the fact that most of the adapted farm machinery was designed to operate at speeds no greater than the clod-hopping gait of a heavy horse.

Harry Ferguson, the inventor of the Ferguson tractor and the man responsible for pioneering the three-point linkage and a system of hydraulic depth control.

Because the trailed machines transferred little or none of their weight onto the tractor, the tractors themselves had to be built heavier with big driving wheels to increase traction. Soil compaction was becoming an issue, but there were other considerations; larger tractors meant less manoeuvrable tractors that were unnecessarily expensive to build and used more fuel. The implements also became heavier as they had to incorporate depth wheels and a self-lift mechanism.

Another problem was that the forces exerted by the trailed equipment in work tended to pull down on the tractor’s drawbar and lift its front wheels. This led to instability, particularly when working or ploughing uphill. Also, if the plough or implement hit a tree root or other hidden obstacle, the tractor was likely to rear up. In extreme cases, tractors were known to turn over with fatal consequences for the driver. The Fordson with its worm-drive rear-axle was particularly prone to overturning and several accidents were recorded.

The old way - towing the plough or implement by a length of chain. The plough was unable to transfer any of its weight on to the tractor and early machines, such as this Saunderson, had to rely on their heavy construction to provide the necessary traction.

Ferguson revolutionised tractor design by combining a lightweight tractor incorporating a three-point hitch with a range of light mounted implements. John Foxwell, the chief engineer of Ford Tractor Operations from 1964 to 1975, once wrote, ‘The three-point hitch is probably one of the most under-rated innovations in this or any other century. It is to the farm tractor what a chuck is to the drilling machine.’ It united the tractor with its implements and turned it from a prime mover into a self-propelled agricultural machine.

The three-point linkage arrangement consisted of a triangulation of hitch points, comprising two lower-link arms, attached low down to either side of the tractor’s rear axle housing, with a single top-link position mounted in the centre above the housing. To this, Ferguson added a hydraulic system to raise and lower the link arms to lift the implement in and out of work.

The hydraulic pump was mounted in the drive line between the transmission and the rear axle. On the Ford Ferguson and TE-20 tractors, it was driven off the power take-off shaft. The pump sucked oil from the rear-axle housing and passed it through a simple control valve to a single-acting ram. The ram cylinder was housed internally above the rear-axle drive-gears. Its piston activated a connecting rod attached to a crank arm that turned a cross-shaft. Lift arms at each end of the cross-shaft were connected via lift-rods to the lower-links. The single-acting hydraulic system provided the power to raise the implement, which then relied on gravity and its own weight to lower itself back into work. The control valve, connected by an internal linkage to a single lever on a quadrant to the right of the driver’s seat, operated the lift. Ball joints at the end of the lower-link arms and top-link allowed the implements to be quickly and easily attached.

The three-point linkage both pulled and carried the implement in work, transferring its weight onto the tractor’s rear wheels. This meant that Ferguson could build a lighter, more economical and cheaper machine, making his tractors more manoeuvrable and more versatile. They could cultivate the most inaccessible corners of fields, work up against walls and hedges, and plough gardens and plots of land too small for even a horse to operate in. Moving from one field to another was also quicker as the implement was carried on the back of the tractor.

The Ferguson way - the TE-20’s three-point linkage both pulled and carried the implement in work, transferring its weight on to the tractor’s rear wheels. The tractor and plough acted as a combined unit that was both light and manoeuvrable.

Ferguson’s converging three-point linkage as seen on the prototype ‘Black’ tractor that was built in 1933. It consisted of two lower-link arms and a single top-link to which the implement was attached.

Another advantage of the system was that the line of pull of the implement at its working depth extended through the converging links of the three-point hitch to a theoretical point just behind the tractor’s front axle. This was known as the ‘virtual hitch point’ and meant that the natural forces affecting the implement in work were converted into a strong forward and downward thrust that held the tractor’s front wheels down. Consequently, the Ferguson was very stable, especially for hillside work, and was unlikely ever to overturn when used correctly.

Other manufacturers also developed simple hydraulic lift units, but Ferguson’s design incorporated a unique and very important feature known as draft control, a system of automatically controlling the depth of the implement. While the latest modern systems boast electronic controls and a host of advanced functions, the first basic hydraulic systems relied on simple position or draft control mechanisms.

Position control allowed the lower-link arms to be either fully up or down, or set at any position in between. This meant that the implement’s height was maintained relative to the tractor, but the system could not control the precise depth of the implement in the ground. With draft control, the link arms could only be fully up or down, and could not be maintained at any intermediate position. However, this system controlled the working depth of the implement in relation to the contours of the land by ‘sensing’ the changing draft present between the soil and the implement. The depth was governed by a sensing mechanism connected to the control valve, receiving signals either through the top-link (top-link sensing) or the lower-link arms (lower-link sensing).

Harry Ferguson can be credited with inventing draft control, and his tractors were the first to use the system. The Ferguson tractor had top-link sensing. The draft force exerted on the implement by the soil was re-directed through the top-link and absorbed by a heavy coil-spring that was connected by a linkage to the hydraulic control valve. When the force coincided with the position set by the driver using the quadrant lever, the valve closed holding the implement at the desired height. As changes in the land increased or decreased the draught force, the valve would open and close to regulate the working depth of the implement. When ploughing, these corrections would happen about once a second.

An illustration of how the Ferguson System utilised the natural forces affecting the tractor and plough in work. The broken arrows show the weight of the implement being transferred on to the TE-20’s rear wheels, while the solid arrow represents the forward thrust that held down the front wheels.

Apart from the obvious advantages of the plough or cultivator maintaining a uniform depth and the driver having finger-tip control over the implement, there were other benefits. The draft control system amplified the weight transference, ensuring the weight of the tractor was automatically adjusted to suit the work or conditions. The implements could also be built lighter and to a simpler design without the need for extra depth wheels. Of great importance was the safety aspect: if the plough hit an obstacle, the system automatically released the weight of the implement, allowing the tractor’s wheels to spin; the tractor came to a standstill and no damage was done. This led to Ferguson’s linkage often being referred to as the safety hitch.

The simplest way to sum up the advantages of the system is to refer to the creed the Ferguson sales and field staff were taught by their instructors: ‘The Ferguson System is a principle of linkage and hydraulic control over the depth at which the implement is working, enabling you to harness the natural forces created by the work that the implement was doing to add weight to the tractor.’ Harry Ferguson’s philosophy was that you did not need a sledgehammer to crack a nut, and he was proved right; not only did his system work, but it also changed the future of tractor development.

To take full advantage of the Ferguson tractor, you needed the correct implements to go behind it. To this end, Harry Ferguson introduced a full line of matched equipment that was eventually expanded to fulfil the needs of virtually every type of farming worldwide. In addition to the mounted implements, there were hydraulically operated tipping trailers and front-end loaders, and a complete range of accessories to make the most of your tractor.

An exploded view of the TE-20 tractor lift mechanism. It shows all the main features of the Ferguson hydraulic system and its internal linkage.

The Ferguson hydraulic lift incorporated a system of draught control that allowed the plough to maintain a uniform depth. The single operating lever to the right of the seat gave the driver finger-tip control over the implement.

Ferguson’s approach to farming went even further once the TE-20 was in production at Banner Lane. He set up an integrated dealer network, pioneered organised service in the field with a fleet of service vans and free on-farm visits, and established a mechanised farming school. Each implement and machine had its own beautifully presented instruction and parts book, and to help with finances there was the Ferguson ‘pay-as-youfarm’ hire-purchase plan. The Ferguson System was more than just a tractor with a three-point linkage and hydraulics – it was a complete vision of global mechanised farming. The result was an almost utopian view of agriculture that was reflected in the brochures and advertising material that were produced by Harry Ferguson’s public relations man, Noel Newsome, a journalist who had been involved in propaganda work during the Second World War.

There were some disadvantages to the Ferguson System. Ferguson himself was fanatical about simplicity of construction – for example, one spanner had to fit all the nuts used on the tractors and implements and be all that was required for all field adjustments. He insisted that only one lightweight size of tractor was needed; however, this was not enough for some of the larger acreage farms that required more power. Like the horses that his machines replaced, Ferguson sometimes seemed blinkered, resisting the demand for larger tractors and losing many sales in the process.

A typical Ferguson demonstration; the roped-off enclosure was used to show how it was impossible to work in such a small and inaccessible area with a horse and plough.

The second part of the demonstration was designed to show how easily and quickly a young lad could cultivate the same plot with a Ferguson tractor. Dick Chambers, who ran the Ferguson School of Farm Mechanisation, normally allocated this task to his son.