15,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

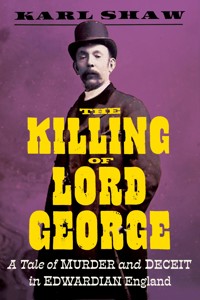

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

'A riveting read ... a dark story of murder and deceit with verve and insight' John Woolf, author of The Wonders THE LIFE AND DEATH OF A 19TH-CENTURY CIRCUS LEGEND On 28 November 1911 a retired showman died violently at his home in North London. Known to the world as Lord George Sanger, he was once the biggest name in show business, and was venerated as a national institution. The death of Britain's wealthiest showman read like a popular crime thriller: a merciless killer; a famous victim; sensational media headlines; a desperate manhunt laced with police incompetencies and a dramatic denouement few could have anticipated. But for over a century, questions have persisted about the murder. Weaving in the story of George's rise to fame and the history of Britain's entertainment industry, The Killing of Lord George uses previously unpublished archive material to reconstruct the events leading up to the death and reveal the true story behind the brutal crime that shocked Edwardian England.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

iii

v

In loving memory of Charles Leonard Shaw 8 May 1931–24 December 2021

ix

‘To Herbert Cooper I leave the sum of fifty pounds.’

The last will and testament of George Sanger (1825–1911)

Contents

Introduction

On 28 November 1911 an elderly retired showman died violently at his home in North London. A coroner ruled that he was battered to death with a hatchet by an insane employee. The victim was a celebrity known to the world as Lord George Sanger. His name was once the biggest brand in show business and for more than half a century he was Britain’s most popular and most successful entertainer, venerated as a national institution.

His death a few weeks short of his 86th birthday was considered one of the most callous murders in English criminal history and it was one of the news sensations of the age. The story read like a popular crime thriller: a crazed, merciless killer, a famous victim, a desperate manhunt and a dramatic denouement few could have anticipated. But for all its dark drama, this was no work of fiction.

The details of the events leading to George Sanger’s death were widely reported but never properly tested in a criminal court. Most people including the police accepted the coroner’s verdict that he was murdered by a young man he thought of as a son, but some, even within the victim’s own family, struggled to make sense of it all. The story hinted uncomfortably at the possibility that there was something rotten at the core. For more than a century, questions have persisted about the murder.xiv

Using previously unpublished archive material including original evidence, witness statements and police documents, this book will reconstruct the events leading up to the evening of 28 November 1911 and reveal the true story behind the brutal crime that shocked and mystified Edwardian England.

All of the words enclosed in quotation marks are reproduced directly from coroner’s court files, police interviews, correspondence between detectives or newspaper reports.

A note about money. Values are difficult to compare across time, but one pound in 1911 had the purchasing power of about £120 in 2021. The Edwardian pound was divided into twenty shillings (worth 5p each of today’s money and abbreviated as ‘s’) and each shilling was made up of twelve pence (thus 2.4 to each 1p and abbreviated as ‘d’). A sum of money expressed as, for example, £5 5s 6d, was five pounds, five shillings and six pence. A guinea was worth 21 shillings.

1

Park Farm

Tuesday 28 November 1911, East Finchley, north London. The long, summer heatwave in the year of King George V’s coronation had given way to the coldest, wettest autumn anyone cared to remember. In East End Road, several days of unrelenting rainfall formed pools of water in the ruts made by the wheel tracks of funeral cortèges servicing the nearby St Marylebone Cemetery. The temperature had not nudged above three degrees Celsius all day.

5.40pm. William Venables, a twenty-year-old butcher’s assistant, was on his bicycle delivering parcels of meat for his employers Pulham & Sons. Battling the evening chill, his collar was pulled high and his chin tucked into his scarf as he pedalled through the dimly lit thoroughfares. His long day began at six in the morning and he was looking forward to being at home. William lived with his parents in a small, terraced house in Brackenbury Road, a poor but respectable part of East Finchley. His 50-year-old father Alfred worked as a gardener in the local cemetery.

Finchley was an ancient village on the Great North Road, the historic highway running out of London to York, 2Edinburgh and all points in-between. It was once notoriously associated with armed robbery, the place where 18th-century highwaymen such as Jack Shepherd and Dick Turpin waylaid carriages as they made the slow journey north. At the junction of Bedford Road and High Road stood the gibbets where the corpses of executed outlaws were hung in chains and left to rot as a discouragement to others. When William Venables’ father Alfred was born, Finchley was a community of small cottages and home to a modest 2,500 souls, some clustered around the mediaeval parish church of St Mary-at-Finchley, others living in the newer settlement of East Finchley. Much of the local work was to service the needs of travellers and of London, with soot and manure out of the city swapped for hay and coal, but the area was also known for its hog markets and dairy farms and the underlying clay was perfect for brickmaking. Although only five miles from the centre of London, it was a world away from the incessant bustle and noxious industries of the city.

Londoners had been attracted to Finchley for centuries, to avoid the plague or more recently for the country air and the pleasing views, but with the arrival of the Great Northern Railway in 1867 the village was transformed into an expanding town for the upwardly mobile. The old horse-drawn coach that ran every fifteen minutes from the Bald Faced Stag to London’s West End took an hour and a half to reach its destination, but the steam train cut the journey to half an hour for 4d a return ticket. The railway brought a decline in the hog markets and the coach trade, but there were new opportunities. The city had a pressing need 3for new burial space. The building of the St Marylebone Cemetery on 57 acres of Newmarket Farm in 1854 brought 10,000 new corpses a year, the dead pumping new life into the local economy with fresh trade for local publicans catering for mourners, a windfall for ornamental stonemasons and steady work for Alfred Venables.

5.45pm. The butcher’s assistant made a left turn onto East End Road. This was once the poorest part of town, crammed with tenements and terraced houses. Like its London namesake, the neighbourhood had a low reputation and contained a largely impoverished and reputedly truculent community. A local vicar who had worked in both said he’d ‘rarely seen the Finchley boy equalled for profanity and rudeness’. But the area was more recently attracting the well-to-do. East End Road’s south-facing slopes were much admired by builders and developers and the thoroughfare was now fringed by several elegant villas set in impressive grounds, suitably distanced from the working-class homes and far enough away from the dirt and smells of the hog markets. One of the biggest residences, Avenue House, was the home of East Finchley’s second-most-notable local, Henry Charles ‘Inky’ Stephens. His father, a doctor who had shared a room at medical school with John Keats, invented an indelible ‘Blue-Black Writing Fluid’ which became famous as Stephens’ Ink and made the family’s fortune. Some of the bigger houses in East End Road had been converted to convents or penitentiaries. One was a Magdalene asylum where ‘fallen women’ laboured in silence all year round in a laundry, their breasts bound and their heads shaved, symbolically washing away their sins. Many of those locked 4away were little more than children, some as young as thirteen. Further eastward on the East End Road, where the houses were smaller and closer together, was the Venables’ local watering hole, The Five Bells. It was favoured by East Finchley’s working classes and was once a venue for bare-knuckle boxing. The champion pugilist William Springall, ‘a barn door in boots’, once fought here before he retired to East Finchley and became a landlord and boxing promoter. He is buried in the nearby cemetery beneath a small headstone bearing the legend ‘Gone but not forgotten’.

5.47pm. The black clouds that had threatened rain all evening were finally releasing a deluge. William Venables put his head down and pushed harder on the pedals, hoping to escape from his errands before the worst of it came. His route would presently take him past Park Farm, one of the best addresses in the neighbourhood and home of East Finchley’s most famous resident. Until a few years ago it had been one of the few surviving dairy farms in the district, before it became the winter quarters of Sanger’s Circus. It was now the retirement home of its celebrity owner ‘Lord’ George. Ahead, by the yellow light of a gas lamp, the cyclist could make out a figure standing by the gate leading into Park Farm, their shadow indistinctly reflected on a roadside puddle of water. As he drew closer he heard a sort of choking yell, then the figure staggered into the road and called out clearly: ‘Will no one help us? Herbert is murdering us!’

Venables slowed. He recognised the figure as Arthur Jackson, a customer at the butcher’s shop and lately an employee at Park Farm. The cyclist came to a halt alongside and saw by the lamplight that there was blood on Jackson’s 5face and shirt collar. Almost directly across the road was a cottage, Park Farm View. Venables abandoned his bike and hammered on the cottage door to summon help.

It was presently opened by a familiar face. His friend, 24-year-old Tom Cooper, worked at Park Farm with his brother Herbert and their father, Thomas senior, the farm bailiff. Tom looked across the road and saw two men illuminated by the flickering street lamp. As he approached he saw that one of the men was reeling and holding his head in his hands. Then he noticed the blood on the man’s face and clothing. Venables urged: ‘Tom, something bad has happened at the farm. You’d better go over there.’

Park Farm stood silent, cloistered by fir trees. Venables watched as his friend Tom entered the premises by the farm gate then disappeared into the shadows. Light spilled from the sash windows of the farmhouse but there was no sign of movement from within. Finding the front door unlocked, Tom Cooper stepped inside. At the end of a passage a heavy oak door to the drawing room was ajar. He pushed on the door and opened it wider. On the floor, near a hearthrug between the fireplace and the dining table, he could see the body of an elderly man lying spread-eagled on his back. He recognised him as George Sanger, the farm owner. Beneath his head a dark trickle of blood was visible. Kneeling, he gently raised the old man’s head and spoke his name but there was no response. He called out to see if anyone else was home. Silence.

Less than a minute later, Venables and Jackson watched as Tom Cooper emerged running from the farmhouse towards them. 6

‘It’s the Guvnor, he needs a doctor quick. Billy, give me your bike.’

The butcher’s assistant surrendered his bicycle and watched his friend pedal off into the darkness.

5.50pm. PC Frederick Nicholls was cold and wet. He was on fixed point duty at Fortis Green Road about a mile and a half from Park Farm. The Metropolitan Police district extended to a radius of about fifteen miles from Charing Cross and covered more than 700 square miles. The force was divided into twenty divisions. In each, as well as local police stations, there were fixed points at which a constable could be found, normally from 9am to 1am, the hours varying depending on local circumstances. They were scattered widely and their locations advertised in newspapers and on police station notice boards. Fixed point duty was the curse of the beat bobby because it was neither challenging nor rewarding police work. PC Nicholls was not allowed to leave his post unless ordered to do so by a superior, even to give assistance if it was needed, to the frustration of the public. In an emergency, a constable thus engaged could only direct someone to the nearest police station or raise an alarm by blowing his whistle so the nearest bobby could respond.

Nicholls swung his bullseye lantern in the direction of a young man approaching on a bicycle. He knew him as one of Thomas Cooper’s sons, Tom junior. The cyclist shouted: ‘Go round to Sanger’s farm at once.’

‘What’s the matter?’

‘I don’t know, but I’m going for a doctor.’

Ignoring his brief, PC Nicholls abandoned his post and set off in double-time towards Park Farm. 7

The St Martin’s Church clock was striking six o’clock as the constable entered by the farm gate. There was no response at the front but finding the back door of the farmhouse unlocked he went inside. The door opened onto a long passage with various rooms off it. On the left at the end was a kitchen. Nicholls recognised the man now standing inside the kitchen doorway as Arthur Jackson and noted the blood on his face and collar.

Jackson spoke: ‘Herbert Cooper did it, and he did the Guv’nor as well.’

Thomas Cooper senior entered the kitchen. He was in his mid-fifties, a little shorter and stockier than his son Tom. Indicating Jackson’s injuries, PC Nicholls asked Cooper: ‘Where is the man that did this?’

Without replying, Thomas Cooper ushered the constable down the passage leading into the drawing room. There Nicholls found the farm owner George Sanger sitting in a chair, bleeding from an ugly wound to his head. He was being attended to by his house servant, Jane Beesley. Nicholls asked Sanger if he could tell him what had happened, but he could see that the old man was barely conscious and in no fit condition to answer. Nicholls went back to the kitchen. On the floor, under the table, he found a broken razor blade with the handle and blade in two parts.

Tom Cooper junior returned to the farmhouse and informed Nicholls that a doctor was on his way. Nicholls instructed Cooper to get a bowl of water to bathe Jackson, then the constable went outside and flagged down a passing cyclist. He asked the man if he knew his way to the local police station. The man confirmed that he did. 8

‘Go there and tell the officer on duty to send someone, a sergeant if possible, round to Sanger’s farm at once. There’s been an attempted murder.’

Ten minutes later Dr William Orr arrived from High Road in East Finchley and he dressed Sanger’s and Jackson’s wounds. A few minutes after that they were joined by the first of several visitors. James Holloway was married to the farm owner’s sister Amelia. He arrived to find his brother-in-law sitting on a chair in the living room with his eyes closed. Holloway, Dr Orr and the Coopers carried the injured man into his ground-floor bedroom and laid him on his bed.

News of the disturbance at Park Farm spread quickly. At 6pm, 31-year-old PC Albert White was mid-way through his shift, proceeding as he was obliged to do at a steady walking pace of two-and-a-half miles an hour, patrolling the area between East Finchley and Church End. The average beat length all over the Metropolitan district was seven-and-a-half miles for day duty and two miles for night duty.1

As the constable turned onto East End Road at the junction of Brackenbury Road he was approached by a woman whose name he couldn’t recall, but he knew she worked at the local off-licence. The woman had a question for White. Did he know if anything had happened at Sanger’s Farm?

‘No, what have you heard?’

‘I hear there is a policeman gone there.’

White thanked her and headed towards the farm. He’d made his first circuit of East End Road past Park Farm not long since and all was quiet, but he decided he’d better take another look. From the road outside the farm, White gave the premises a cursory once-over but could see nothing 9suspicious. Satisfied that his detour was a wasted effort he went on his way, but when he got as far as Church Lane he thought better of it and turned back. He knocked at the front door of the farm and it was opened by a familiar face, that of the farm bailiff Thomas Cooper senior.

‘Has anything unusual happened here tonight, Mr Cooper?’ The constable could already see from the man’s expression that something had.

Cooper replied quietly. ‘One of your comrades is here, you’d better come in.’

In the kitchen, the constable found PC Nicholls and two men with their heads heavily bandaged. One of the injured men PC White already knew as Arthur Jackson, the other he learned was Harry Austin, an equestrian who worked for George Sanger’s circus. Austin, they learned, had also been injured during the incident and had returned having fled to seek help. PC Nicholls took his colleague to one side.

‘There’s a big assault job gone on here.’

‘What have you done about it?’

Nicholls explained that there were no telephones at Park Farm, so he had sent a passing cyclist to relay a message to the police station.

‘Can you trust him?’ Without waiting for a reply, PC White instructed Nicholls not to allow anyone else to enter the house and hurried off to find the nearest phone.

7.50pm. At Finchley station, 45-year-old Sub-Divisional Inspector John Cundell took a phone call from PC White at the Five Bells public house. White informed him that ‘something serious’ had happened at Sanger’s and a senior officer was needed there immediately. Cundell made a note of the 10time, then took his bicycle and made haste to Park Farm, arriving at about 8.20pm. He found White standing sentinel at the door. The constable’s job was to preserve the integrity of any evidence that existed, but Cundell found the crime scene already busy with anxious members of the extended Sanger household, including James Holloway, the housemaid Jane Beesley, the farm owner’s grand-daughter Ellen Austin and her sister-in-law Agnes Austin. Soon they were joined by the police divisional surgeon Dr Baker.

Cundell debriefed the two constables who were first at the scene, then took statements from the two injured men, Jackson and Austin. He then went to check on the farm owner, who was lying limp and insensible on his bed. The police inspector thought it likely he was already beyond any medical help that could be offered. All the doctors could do was make their patient as comfortable as possible.

In the drawing room, Cundell noted signs of a struggle. Opposite the door stood a grand stone fireplace. On the mantlepiece there was a broken glass-fronted clock. On the floor on the opposite side of the room, a large, heavy, bronze diamond-shaped candelabra lay broken in two pieces. On the base of the candelabra there was a blood stain. The fire irons had been knocked into the grate. On the floor there was a black, hard felt hat, badly damaged with a chunk of it lying adrift nearby and some shards of glass, presumably from the clock. There was a bloodstain on the floor near the hearth and a second blood stain on the end of the table nearest the door.

Cundell returned to the injured man in the bedroom. He was comatose and dying – Doctors Orr and Baker were quite 11certain they could do nothing to prevent that – but there was at least a small hope that he might recover consciousness long enough to confirm the identity of his attacker. Cundell made arrangements for the attendance of a justice and a justice’s clerk to take the old man’s dying deposition, just in case.

By 8.30pm the police presence at Park Farm had grown to include the two men who would be taking charge of the case, Detective Inspectors George Wallace and Henry Brooks of the Metropolitan Police S (Hampstead) Division. Wallace and Brooks were annoyed, having arrived at the crime scene to find it swarming with people. Because of the delay in reporting the incident, before any pursuit could commence in earnest, the perpetrator would have a head start of more than three hours. In this chaotic situation the investigation continued. Taking charge, Wallace made his displeasure known to Cundell and issued a sharp instruction to organise a thorough search of the farm outbuildings.

Park Farm was once the hub of a thriving dairy business covering hundreds of acres. Set in large gardens, the farmhouse and courtyard were flanked by outbuildings, easily visible beyond the low stone wall fronting the premises. It was little altered since George Sanger bought it in the mid 1890s, although of the original 200 acres of grazing land, sloping away towards Hampstead Heath and Golders Green, about half had been sold off to the new Hampstead Garden Suburb development for the building of residential homes. The old farm property was a long, straggling building built at right-angles to the East End Road, comprising two large yellow sandstone cottages knocked into one. Over the porch of the front door of the cottage nearest the roadside there 12was a royal coat of arms, a relic of Astley’s Amphitheatre on Westminster Road and a reminder of the times when the famous owner performed for the late Queen Victoria and her son the Prince of Wales. Inside, to the left was a large drawing room containing a fireplace, two chairs, a table and a sideboard. Wallace and Brooks noted the signs of a struggle, including the splashes of blood on the floor and the edge of the table. They made notes, but no photographs were taken. Cameras had been used to capture images of convicts for more than 40 years but no one in the Metropolitan Police thought them useful to routinely record crime scenes.

In the drawing room and throughout the house, on sideboards, mantlepieces and in corners, there were mementos of the owner’s former life and travels, including several large statues of famous circus horses. He had a particular fondness for silver plate and there was a considerable quantity of it lying around, including silver soup tureens, candelabra and a large, eye-catching silver cup, labelled ‘Presented by the Prince and Princess of Wales’. From the drawing room, there was a long corridor with ground floor rooms off it, including the kitchen, pantry and scullery and a downstairs bedroom. Park Farm was a substantial property with several upstairs bedrooms, but after more than 80 years of living in a caravan, the owner had never got into the habit of climbing stairs to go to sleep. In the kitchen, on a mantlepiece, the senior detectives noted a bloodied cut-throat razor with the blade tied open with a piece of string.

In addition to the main house there were various outbuildings, including four stables and two fowl houses forming three sides to the square cobbled courtyard. To the 13left rose a curious-looking building, a high barn with huge glass doors. This was Sanger’s former elephant house. In front of the building there was a bench on which was placed an elephant’s skull. According to local legend, it belonged to a beast that broke loose at Crystal Palace and killed his keeper. There were also a few ducks, geese and pigeons. A parrot on a pergola screeched George! George! George! while a large dog forlornly wandered the courtyard.

At the front of the premises nearest to the road there were two small garden enclosures and a path between them to the right sloped away to a large circular duck pond. In the gardens there were large fir trees and chrysanthemums growing wild among the borders of the lawns. Until their owner’s retirement six years ago, a great menagerie had wintered at the farm, but now the only survivors from the circus days were four small ponies and two black piebald horses in an outbuilding. George Sanger had occasionally used them to drive up to the town, but the horses, like their master, were now old and worn.

In a space between one of the two fowl houses and a stable, the police found signs that someone had fixed up a makeshift bedroom. In this den, one of the many officers milling around the scene had found an old unloaded six chamber Enfield revolver. It was recorded in the evidence book, but no one was particularly excited by the discovery. It was an obsolete standard-issue firearm of the armed forces and there were plenty of them in circulation. There were no clues as to the owner’s whereabouts or his state of mind.

More police officers were arriving by the minute from nearby S Division stations. By 9pm Wallace and Brooks 14about a hundred uniformed men at their disposal, scouring the surrounding district by lantern light. An officer was sent by cab to contact all the fixed pointsmen on the route between Swiss Cottage and East Finchley and supply them with a description of Cooper. Meanwhile the two senior detectives were trying to piece together Herbert Cooper’s movements earlier in the day and were taking statements from his father and his brother.

By 10pm Wallace and Brooks had marshalled the basic facts of what they believed had taken place at Park Farm earlier that evening. From testimonies given earlier, they learned that until five weeks ago, Herbert Cooper, 26-year-old son of the farm bailiff Thomas Cooper and older brother of Thomas John Cooper, had served at the farm as personal attendant to George Sanger. Herbert Cooper had worked for Sanger in this capacity for about six years and he had the run of the house. He slept in Sanger’s room, read newspapers to him, accompanied him on trips into town and generally acted as his confidential helper. For reasons yet to be determined, Herbert Cooper had fallen out of favour and his job had been taken by Arthur Jackson. Cooper was still working on the farm as a general labourer but was no longer allowed in the house and was thought to have been sleeping rough in one of the farm outbuildings.

It appeared that Herbert Cooper had taken the loss of his status badly. At around 5.45pm that evening he entered the farmhouse and went into the kitchen where Jackson was sitting alone at the table, reading. Cooper told Jackson he had come to retrieve his gramophone from the pantry, but then Cooper attacked him from behind, slashing at his throat 15with a cut-throat razor. There was a furious struggle and Jackson was left bleeding and semi-conscious on the kitchen floor.

Harry Austin meanwhile was sitting with George Sanger in the drawing room when they were interrupted by a noise from the kitchen. Austin went to the door and saw Cooper charging towards him wielding a large, heavy axe above his head. Austin tried to block his entry by closing the door, but Cooper was too powerful for him. In a wild, frenzied attack, Cooper first set about Austin, then the defenceless Sanger, battering them with his weapon. Leaving both men for dead, Cooper fled the scene and disappeared into the night. Neither Jackson nor Austin had any doubts about the identity of their assailant.

Two police officers had waited by the stricken man’s bedside in the hope that he would rally sufficiently to give them a statement, but George Sanger did not recover consciousness. Doctors Orr and Baker jointly pronounced life extinct at precisely 11pm. The manhunt for his murderer was on.

2

Press gang

It’s not altogether clear exactly when George Sanger was born. When it came to details of his past he had a complicated relationship with the truth, or you could say he had a showman’s flair for telling tales. It was most likely in 1825 but he always claimed that he was a couple of years younger.2 We only know for certain that the happy event took place in the market town of Newbury in Berkshire. His father James was a travelling showman, one of many itinerant performers who tramped the roads from March to October working the country fair circuit. Some of his fellow travellers did it for the love of the trade and some married into it. Many found the nomadic life a convenient hiding place from a problem left behind, perhaps a broken marriage or something much worse. Others drifted into it for want of anything better to do. For James Sanger, the showman’s life was the choice between the devil and the deep blue sea.

The Sangers were Wiltshire people. According to a romantic family lore, they were once mediaeval wandering minstrels who came to England in the early 13th century. Another version holds that a Sanger was a jester in the 18court of King John. It’s more likely they were strolling Yiddish performers from Germany. Sanger was a common German-Jewish surname and since the early 1700s Jews provided two-thirds of the travelling showfolk of England. When he was an old man, George would refer to the Hebrew market traders of north London with affection as ‘my people’, to the bafflement of younger members of his family who had never before considered that any Jewish blood may run through their veins.

For many generations the Sangers were tenant farmers, tilling the fields around the village of Tisbury on the edge of Salisbury Plain. As soon as he was old enough, James Sanger was apprenticed to a toolmaker in town. On his day off, his father put him to work around the farm. When he was not quite eighteen, James said goodbye to his mother and father and set off with his elder brother John to visit some friends in London. It was the last time James ever saw his parents.

It was December 1798 and Britain was at war with France. The beat of the recruiting drum was sounding in town squares and on village greens all over the country. Britain’s strength lay in its navy, as it had for a hundred years and more. In London, James and his brother were making their way across London Bridge when they heard the cry ‘Press! Press!’ Impressment was the age-old right of the Crown to the labour of seafarers in time of war and press gangers roamed the towns and cities, taking men against their will to serve, making sons and husbands disappear for months, even years on end. The Sanger brothers fled in opposite directions. John ducked into a druggist’s warehouse where the proprietor’s pretty daughter allowed him to hide.3 James 19spent the night in a barrel under the bridge, but when he emerged the next morning another group of gangers was waiting. He fought back with fists and feet but was heavily outnumbered and battered into submission. An hour later, bloodied and bruised, he found himself on a ship near Deptford with about 150 fellow victims, scooped up to fight Britannia’s battles on the high seas. A few days later, James Sanger was transferred to HMS Agincourt and he and his fellow recruits were mustered on deck to hear the harsh rules that would govern their daily life. Some of those on board would have already showed the livid cross-hatching of scars where their backs had been subjected to the lash. It was used liberally to tame reluctant sailors, every stroke biting into their flesh. Below deck, James was packed with hundreds of men into a cramped, fetid space stinking of unwashed bodies, tobacco, tar and sewage. Sickness spread easily and typhus, cholera and dysentery posed a greater threat to sailors than battles at sea. On deck they were at the mercy of the weather and novice sailors were often blown overboard and drowned. From the deck of HMS Agincourt James witnessed a terrible storm and saw two warships go down.

After a couple of years he was transferred to HMS Pompee. It was captured from the French at Toulon and was now a 74-gun Royal Navy ship of the line, a brute killer of the deep. In the Caribbean, James saw his first action. HMS Pompee was designated flagship of a British invasion force to capture the French West Indies. It was equipped with carronades, lightweight guns known as ‘smashers’ because of the destruction they wreaked at close range. For three days and nights James’s ship was engaged 20in a 500-mile running battle with the French flagship Hautpoult. On 17 April 1809 the Hautpoult’s mizzen mast was brought down and the Pompee drew alongside to use her carronades to deadly effect. Below deck it was hot and airless and every surface shook from the thunderous recoil of guns. Men wrapped scarves around their heads to protect their ears from the pounding of the cannon. Competing with the stench of blood and burning flesh were the screams and moans of the wounded and dying from every corner. After a terrifying 75-minute exchange of fire, the crippled Hautpoult surrendered having sustained heavy casualties, and was taken as a prize. Back at Dartmouth, there was an outbreak of typhus on the Pompee. Two men went down with symptoms of ‘vomiting, a foul tongue, quick pulse and pain in the head, back and loins’.4 One died the next day and within a week many more were taken ill.

Between the risk of disease, the lash and the thunder of cannon, James’s most regular enemy was boredom. Routine was important for discipline because if it broke down there was the risk of mutiny. Time passed slowly, every day a ritual of scrubbing, cleaning, painting and sewing, but then one day there was an exciting arrival that would change the course of James Sanger’s life. While the Pompee was moored at Deal, the ship was visited by bumboats ferrying supplies and trafficking with the sailors. One of the boats carried the brothers Israel and Benjamin Hart. They were strolling conjurers seeking to earn some money by performing for the crew. Their enterprise was cut cruelly short when the ship’s captain found out the Harts had naval experience and he seized them for the service of the King. But it was 21James’s good fortune. He enjoyed the company of the Hart brothers and in-between duties his new friends taught him some simple conjuring tricks.

Family legend has it that James Sanger was transferred to Nelson’s flagship HMS Victory and served on her at Trafalgar. In the thick of the battle, he and 25 others boarded an enemy vessel. Eleven of his shipmates were killed in action while James sustained a severe head wound, smashed four ribs and lost several fingers. He was back on the deck of the Victory in time to see Horatio Nelson fall. In 1815, ten years and eight months after he joined, James Sanger left the Royal Navy.5

Britain’s naval triumphs were followed by thousands of personal tragedies among the people who had made them possible. Almost a third of those who fought died from wounds or fever and the bulk of the rest faced redundancy. The King and his government cared little for the welfare of the laid-off seaman. Officers retired on half-pay, but for those among the lower ranks the return to civilian life was cruel. Dismissed from the services without pension or acknowledgment, James Sanger and his fellow returning sailors found themselves adrift in an economy that was shrinking fast and a labour market that was already overcrowded. After nearly eleven years away, James went home to find his parents long dead and little sympathy from his siblings. Perhaps they reminded him that he had abandoned his family for a reckless adventure at sea while they bore the brunt of the worst economic hardship anyone could remember. Now he was back, not a returning war hero, but a nuisance and a burden. Harsh words were exchanged and James left never to return. 22

The Wiltshire country roads were full of people on the move, some like James Sanger recently returned from the war, others habitual vagabonds, thrown out of parishes because they could prove no right to poor relief. The French wars had been running endlessly and a series of bad harvests had savagely driven up the price of bread. There was hunger everywhere. On the roadside, nettles sold for twopence a pound, to be eaten with salt and pepper as a substitute for potatoes. In every town and village there were discharged soldiers and sailors, many badly injured or mutilated by amputations, destitute men with no alternative future but crime or beggary and an early death in the workhouse.

Remembering the conjuring tricks he’d learned from the Hart brothers, James Sanger decided to try his luck as a showman. Even in the worst of times, there were fairs and fetes in Regency England everywhere from south to north. They were the perennial climaxes of the holiday calendar, part of the seasonal rhythms of rural life. Most fairs had ancient origins as places for traders to show their wares. They attracted saddlers and harness makers, cloth traders from Yorkshire, earthenware sellers from the Potteries and dairymen bringing their cheeses from Derbyshire and Cheshire. There were also statute fairs or ‘mops’ held for the autumn hiring of agricultural labour. Entertainers followed close on their heels. Amid the ribbon sellers, trouser salesmen and ‘scrapers of cat gut’ there were swing boats and merry-go-rounds and stalls selling sugar plums, lollipops and gingerbread. Over time, the business side of the fairs faded away and they became places of pleasure and entertainment. 23

The variety of ways that men, women and children found to turn a penny was infinite. Rope and wire dancers competed with conjurers, tumblers, clowns and trick-riders, hurdy-gurdy players, dancing booths, glassblowers and Chinese sewing-needle swallowers. There were freak shows, human and animal. At Bartholomew’s fair in London you could see ‘a Mare with Seven feet,’ a misshapen sheep, a young Oronatu Savage, a 120-stone hog, ‘the smallest woman in the world, Maria Teresa the Amazing Corsican Fairy’, a giantess from Norfolk and ‘a man who performed the disgusting feat of eating a fowl alive’.6

At Bristol Haymarket James Sanger tried to prise a few pennies from reluctant pockets, inviting passers-by to judge his sleight of hand: Step up for a little hanky-panky. One, two, three – presto – begone! I’ll show your ludship as pretty a trick of putting a piece of money in your eye and taking it out of your elbow, as you ever beheld!

He invested his earnings in a portable peep show. It was the most basic of entertainments, the staple of fairs, wakes and market days. There were hundreds of peep-show operators working the big cities, many of them military veterans like James. His humble show was contained within a large box on a folding trestle which he carried on his back. The box had six peep holes fitted with lenses through which customers were invited to peer. A penny or a halfpenny bought a performance comprising a series of crudely painted scenes attached to strings, lowered into view as the spectator kept his eyes glued to the hole. These scenes illustrated a story narrated by the operator, the whole made more plausible by very dim illumination from tallow candles. The perennial 24favourite subjects of the peep show were notorious murders and famous military victories. They were exhibited over and over until they fell apart and it was often only through the showman’s expert patter that anyone could guess which conflict the scene represented. Charles Dickens saw a wornout peep show that had ‘originally started with the Battle of Waterloo and had since made it every other battle of later date by altering the Duke of Wellington’s nose’.7

James’s first show was the Battle of Trafalgar. He was a natural storyteller and he quickly picked up the spieler’s art. As his customers craned their necks, straining to make sense of the dimly lit images within, he seduced them with dramatic tales about the famous battle he claimed he had actually fought in. Daily he tramped the thoroughfares carrying his simple peep show on his back, setting up a pitch wherever pedestrian traffic was heaviest. There were many times when he was sodden, frozen and there were no customers in sight, but at least he kept starvation at bay.

At Bristol Haymarket he met Sarah Elliott, a lady’s maid. After a brief courtship they were married at Bedminster where Sarah’s mother kept the Black Horse inn. The couple settled at Newbury where James had relatives in the fruit and vegetable trade. Newbury was a small market town on the River Kennet, straddling the roads to London and Bath. Through the winter the couple earned a living shuttling back and forth to London, dealing in fish and fruit, which they sold from a stall every Thursday in the marketplace. For the rest of the year they were travelling show people, James carrying the peep show on his back while Sarah sold toffee apples from a tray for a halfpenny each. 25

When Sarah gave birth to their first child, the small family was able to live cheaply lodging with relatives. The need for larger accommodation became a pressing concern with the swift arrival of a second. James rented a small house on Wharf Road near to the market square where the stocks still stood. Tramping the country roads on foot with small children in tow was no longer an option, so James got together the materials to build his first caravan. It was a primitive affair, the roof and sides made from thin sheets of iron. In the summer it was suffocatingly hot inside and so bitterly cold in winter that they preferred to sleep in a tent, but on the whole it made travelling more tolerable.

James’s show was evolving too, with a new source of income, a makeshift children’s roundabout. He made some wooden horses, crudely fashioned from sticks and half-inch deal boards covered with rabbit skin, painted up in white with red and blue spots. Horsepower was supplied from local boys at the fairs, happy to push the contraption around for the reward of a ride later. Travelling in a caravan also meant that James could carry a bigger and better peep show. His new deluxe version had 26 apertures and new painted scenes supplied by a drunken Irishman who charged three-shillings-and-sixpence for battle scenes, seven-shillings-and-sixpence for extra corpses. James’s convincing patter did the rest.

While touring the West Country, he added some daring new attractions to his mobile show to sate the Victorian public’s appetite for ‘human curiosities’ – Madame Gomez ‘the tallest woman in the world’ and two ‘savage cannibal pigmies of the Dark Continent’. The acts relied heavily on 26James’s ingenuity and powers of persuasion. The exotic Madame Gomez was neither foreign nor very tall, but where nature fell short, a raised platform and long skirts provided. Similarly, the ‘savage cannibal pigmies’ were not as advertised. Trumpeted as ‘fully grown, being, in fact, each over thirty years of age’ they were supposedly captured by Portuguese traders in the African wilds: ‘incapable of ordinary human speech … their food consists of raw meat, and if they can capture a small animal, they tear it to pieces alive with their teeth, eagerly devouring its flesh and drinking its blood’.8

In reality the pygmies were talkative brothers aged nine and ten years, borrowed from their Irish father and black mother who lived in Bristol. Feathers, beads and greasepaint gave them the requisite verisimilitude. The credulous folk of the West Country were hugely impressed, but the authorities were not. James Sanger was forced to abandon his display of living cannibals when he was reported for operating at Plymouth fair without a licence. He fled the district to avoid arrest and his wife and family caught up with him later at Newbury. His performing ‘cannibals’ were removed to the Bristol workhouse. It was James Sanger’s very last experiment with freak-show acts.