9,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: anna ruggieri

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Sprache: Englisch

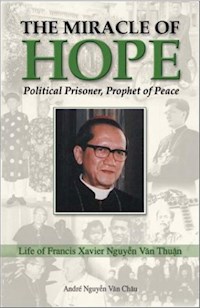

Written by a personal friend of Cardinal Thuan, this moving biography—containing over 70 photographs and writing excerpts—chronicles the life of the man Pope John Paul II said was “…marked by a heroic configuration with Christ on the cross.” From a prisoner in a communist jail cell to a leader of the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace in Rome, Francis Xavier Nguyen Van Thuan remained a man of unshakable faith and undying hope.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Andre Nguyen Van Chau offers a superb account of the life and spirituality of one of the great Catholic leaders of our time. Cardinal Van Thuan was not only a friend to many of us in the College of Cardinals, but he remains a vibrant source of hope for all of us in the Church because of the way he lived in perfect conformity to the Crucified Christ.

—His Eminence Cardinal Roger MahonyArchbishop of Los Angeles

He is an icon of the Vietnamese Catholic Church: Francis Xavier Nguyen Van Thuan. The lines of his story tell of a country and a people torn by the horror of violence and war brought on by their struggle for independence. His is an unapologetically political spirituality that is cultivated, nurtured, and sustained by the riches of the Catholic tradition. Written at the late Cardinal’s own request, this biography charts the footsteps of a man who walked the long road of hope, urging us on to hope amidst the darkness of our own time and place.

—Michael DowneyAuthor, Hope Begins Where Hope Begins

Van Thuan survived a nightmare in human history and transformed it into a dream for a future of the Church and of humanity. A story unbelievably complex, a message incredibly simple: hope alive in one person can reform the world. A book for anyone who needs to keep their courage alive…

—Sr. Helen PrejeanAuthor, Dead Man Walking

The power of simplicity is witnessed both in the life of this holy man and in its narrative. Written in a straightforward, unadorned style, which only serves to underscore and complement the intensity of Cardinal Van Thuan’s message, The Miracle of Hope takes us on an inspirational journey, accompanied by both detailed descriptions of the natural beauty that blessed his beloved, strife-torn homeland of Vietnam, and the extraordinary spiritual beauty that radiated from within his soul. Thuan’s motto, “Do not turn spiritual values into material possessions,” is one we would do well to heed, and the triumph of his hope, despite the numerous trials he was asked to endure, is the miracle Cardinal Van Thuan has passed on to humankind.

—Dr. Elvira di FabioHarvard University

Cardinal Van Thuan’s greatest heritage is the Gospel in the purity of its message: a message of love and of reconciliation. Even to his last breath, he breathed this Gospel, which was the tranquil force of his entire life.

—His Eminence Cardinal Roger Etchegaray President EmeritusPontifical Council for Justice and Peace

I have been deeply moved by the example and writings of Cardinal Van Thuan. Any reader with Christian values will find in his biography and writings a new insight into Christian faith, hope, and charity. Having met the Cardinal on the day of his elevation to the cardinalate, I knew I was meeting someone very special. There was a certain inner light that touched everyone who spoke to him that day. I have only experienced this one time before—when I met Mother Teresa.

—Rev. Benedict Groeschel, CFRAuthor, Arise from Darkness

An outstanding biography of a “prisoner and prophet,” The Miracle of Hope captures the culture of social awareness and information media that inspired Cardinal Van Thuan from the beginning of his life. His well-honed skill at discerning the difference between truth and falsehood in national and world affairs was due, in great part, to his mother. Cardinal Van Thuan is a prophet for Gospel justice and peace. His story is a biography for our times.

—Sr. Rose Pacatte, FSPAuthor, Lights, Camera…Faith!

Reading these pages is like making a retreat with a saint. Cardinal Van Thuan personifies the title of his book, The Road of Hope, written on scraps of paper, smuggled out of prison, and based wholly on Gospel passages he himself had lived. From 13 years of torture and imprisonment, 9 of them in solitary confinement, he emerges full of hope in God. From the horror of war in his native Vietnam he knows war’s waste of human potential and becomes an anti-war activist devoted to the dignity of the human person. From his extraordinary life and convictions we take hope for our own time and the knowledge that in the end, only holiness matters.

—Rev. Murray Bodo, OFMAuthor, Poetry as Prayer: Denise Levertov

Cardinal Nguyen Van Thuan, whom my family and I are blessed to have known personally, is now being venerated the world over as a “martyr”—that is, witness—of the Christian faith. Until now, little has been known about him in the English-speaking world except that he was President of the Pontifical Council of Justice and Peace, and through the translation of some of his books. We are grateful that now an authoritative biography is available for English readers. It is my fervent hope that through The Miracle of Hope, people of all faiths will be spiritually enriched by Cardinal Thuan’s message, and in particular by his living testimony to the possibility that suffering can be a source of intimate union with God and loving solidarity with one’s fellow human beings.

—Dr. Peter C. PhanProfessor, Chair of Catholic Social ThoughtGeorgetown University

I am as moved in reading these stories now as I was when I first heard them, during my personal encounters with Francis Xavier Nguyen Van Thuan, which began about a year after his exile from his beloved homeland. The gentleness of this saintly figure will remain with me as long as I live. This stirring and finely written account of a man who came from a dynasty of martyrs will bring the reader into the heart of a meek soul whose strength enabled him to endure much, because he loved much. This is an ideal book to take on a retreat.

—Rev. Robert A. SiricoPresident, The Acton Institute

The Miracle of Hope

Francis Xavier Nguyen Van Thuan

Political Prisoner, Prophet of Peace

By Andre N. Van Chau

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Van Chau, Andre N.

The miracle of hope : Francis Xavier Nguyen Van Thuan, political prisoner, prophet of peace; / by Andre N. Van Chau.

p. cm.

ISBN 0-8198-4822-0 (pbk.)

1. Nguyen, Francis Xavier Van Thuan, 19282002. 2. Political prisoners–Vietnam–Biography. 3. Cardinals–Biography. I. Title.

BX4705.N53 V36 2003

282’.092dc21

2002015652

The Scripture quotations contained herein are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible. Catholic Edition, copyright 1993 and 1989 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the U.S.A. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without permission in writing from the publisher.

Copyright 2003, Daughters of St. Paul

Printed and published in the U.S.A. by Pauline Books & Media, 50 Saint Pauls Avenue, Boston, MA 02130-3491.

www.pauline.org

Pauline Books & Media is the publishing house of the Daughters of St. Paul, an international congregation of women religious serving the Church with the communications media.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 11 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 03

This book is dedicated to Sagrario, my wife, and to my children, Andrew, Boi-Lan, Michael, and Francis-Xavier, who have had an unshakable faith in Cardinal Francis Xavier Nguyen Van Thuan

It is also dedicated to Cardinal Nguyen Van Thuan’s parents, his brothers and sisters, and to all those who have believed in him and drawn strength from his presence and his words.

Vietnam.

A country of breathtaking beauty and unrelenting tyranny, of tropical heat and passionate ideals, of powerful memories and recurring nightmares. Even today, a country little known and even less understood.

And woven into this country’s history: the Ngo Dinh family, descended from Christian patriots, destined to play a part in the glory and tragedy of a beloved country in the middle of the twentieth century. Cardinal Thuan knew the weight of belonging to such a family. His dedication to peace, mercy, justice, and compassion came from a spirituality burnished by political association.

Despite the ambiguity and intrigue, the whispers of plots and of coups that surrounded his family, Thuan loved and embraced his mother and father, aunts and uncles, brothers and sisters and cousins as just that—family. Thuan saw his family as men and women who paid a high price for faithfulness to what they believed was true.

Here they are seen through Thuan’s eyes—for this is his story.

Contents

Acknowledgments

Prologue

Author’s Note

Part One: A CRUEL AND ENCHANTING WORLD

Chapter One The Seeds of Faith

Chapter Two A Vocation of Patriotism

Chapter Three Growing Up in Hue

Chapter Four An Ninh Minor Seminary

Chapter Five The World in Turmoil

Chapter Six Japan’s Victory and Defeat

Chapter Seven An Era Ends

Chapter Eight The First of Many Tragedies

Chapter Nine Phu Xuan Major Seminary

Chapter Ten The Young Priest

Chapter Eleven Ngo Dinh Diem Comes to Power

Part Two: THE SPIRITUAL JOURNEY

Chapter Twelve The Urbana Institute

Chapter Thirteen Going Home

Chapter Fourteen In the Shadow of Power

Chapter Fifteen Broken Dreams

Chapter Sixteen The Rebirth of Hope

Chapter Seventeen Bishop of Nha Trang

Chapter Eighteen The Mission of Love

Chapter Nineteen The Fall of South Vietnam

Part Three: THE STORMY YEARS

Chapter Twenty The Ordeal Begins

Chapter Twenty-One The Road of Hope

Chapter Twenty-Two Inside North Vietnam

Chapter Twenty-Three Return to Solitary Confinement

Chapter Twenty-Four Light after Darkness

Part Four: THE TRIUMPH OF HOPE

Chapter Twenty-Five Freedom and Exile

Chapter Twenty-Six The Man with a Gentle Smile

Chapter Twenty-Seven President of the Council for Justice and Peace

Chapter Twenty-Eight The Dream Goes On

Chapter Twenty-Nine The New Cardinal

Epilogue

Glossary of Characters

About the Author

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to acknowledge that he received many of the photographs included in this volume from Cardinal Thuan himself, and from Cardinal Thuan’s brother, Nguyen Linh Tuyen. He would like to thank Cardinal Thuan’s sisters, Thu Hong, Ham Tieu, and Anh Tuyet, for the photographs they contributed.

The author also wishes to acknowledge everyone at Pauline Books & Media for their collaboration on this project, especially Linda Salvatore Boccia, FSP, Helen Rita Lane, FSP, and Madonna Therese Ratliff, FSP.

Pauline Books & Media would like to thank Lt. Col. Richard J. Alger, USMC (Ret.), who served as a commander in Vietnam, for reviewing the text.

Prologue

God made human beings straightforward, but they have devised many schemes.

Ecclesiastes 7:29

Abraham set out with the hope to find the Promised Land. Moses set out with the hope to free his people from slavery. Jesus himself set out: he came down from heaven with the hope to save mankind.

The Road to Hope, F. X. Nguyen Van Thuan

Gentle and smiling, Cardinal Francis Xavier Nguyen Van Thuan would always advance toward his visitors with both hands extended in welcome. They soon noticed that he smiled more often out of his shyness than from mirth. Yet, even when not smiling, his countenance conveyed a warmth and reassurance. People felt comfortable in his presence; they felt at home with him.

He spoke slowly, choosing his words with absolute precision. His voice was soft and his speech eloquent in its simplicity. It was obvious that his simple ideas came from a great interior depth, and for those who heard him speak, his words became an invitation to soul-searching reflection.

Cardinal Thuan never changed his manner whether he spoke to a large audience, a small group, or to one person. He began with things familiar and gradually turned them into something startlingly new. He could quickly endow the seemingly trivial, the commonplace, and things usually taken for granted with new meaning so that they became attractive subjects for contemplation and beckoned the imagination.

Those who came to know him soon realized that they would have to abandon their entrenched views and comfort zones if they wished to follow him on the same intellectual and spiritual adventure he had experienced, and enter the fresh reality his words had thrust upon them.

Indeed, those who met Cardinal Thuan very often came away richer not merely in ideas, but in entirely new perspectives. Cardinal Francis Xavier Nguyen Van Thuan seemed always ready to offer the marvelous gift of his refreshing insight to everyone he met.

For the Jubilee Year 2000, Pope John Paul II invited the then-Archbishop Thuan to preach the annual Lenten spiritual exercises for him and the Vatican curia. The archbishop responded to this personal request with great humility and enthusiasm.

On the first day of the retreat, he startled his audience, telling them that he loved Jesus because of his “defects,” and then proceeded to enumerate them. Instead of rebuking the archbishop for his unusual meditations, Pope John Paul II and the curia were enthralled. In fact, upon the pope’s recommendation, the sermons were soon published in several languages. Testimony of Hope, as this series of sermons came to be known, reveals Thuan’s humility and simplicity and illustrates how he touched people’s hearts by allowing them to see familiar realities in a new light.

Cardinal Thuan was also a good listener. When speaking with him, one had the impression that he did not listen merely with his ears. It seemed his whole being was open to receive whatever someone might say, to hear and understand even a person’s silence.

His door was permanently open to everyone. Though he was extremely attached to his family and friends, they never monopolized his attention. In fact, he tended to show some restlessness whenever too long in the company of friends, as if he were reminding himself that he could not give his life and time to only a select few.

I knew Francis Xavier Nguyen Van Thuan from the time he was eighteen. Our grandfathers had worked together on the construction of a church and our families have remained friendly since then. Later, Thuan and I attended seminary at An Ninh during the same years, although Thuan was four years my senior.

What struck me most whenever I saw Thuan was his great courtesy. He showed respect to all who crossed the path of his life, including those who betrayed, persecuted, or tortured him. Despite the depth of his thought, he remained as simple as a child. He accepted his vulnerability as the natural price for his sincerity and openness—characteristics certainly difficult for him to maintain, considering the harm people have done him and his family.

His life story is fascinating, yet the dramatic and often tragic events that fashioned him were dwarfed by the magnificent spirituality they fostered within him. And those who might feel tempted to see his life as a succession of dramatic moments apart from his faith in God miss the essential point. The dramas and tragedies that wove the rich fabric of his life definitely affected him in one way or another, but Thuan became the man of God he was because of and despite them.

To write about Thuan is no easy task, and the main difficulty lies in understanding his spirituality in order to convey it effectively. To my knowledge, few biographers attempt to write about a person’s spirituality, for even the most naïve realize that such an undertaking is as daunting as the literary critic who tries to exhaust the beauty of a poem; a theologian who tries to describe faith; a Buddhist thinker who endeavors to express his or her vision of Nirvana. They would be better off trying to empty the ocean with their cupped hands. This is because spirituality is something experienced, not described. And yet, writing about Thuan without touching upon his spirituality would be to tell a meaningless story, it would be as if one took God out of his life—an impossibility.

To really come to know and understand Thuan, one should carefully read two of his books: The Road of Hope, written in 1975 while he was in prison, and Five Loaves and Two Fish, which was published in 1998. Both books trace the journey of his soul and allow the reader a glimpse into the vast expanse of the life of a beleaguered and suffering man who clung to hope and who, paradoxically, embraced life with intense joy at precisely those moments when it seemed an unbearable burden.

Some years ago, after I completed a biography of his mother, Thuan asked me to write about his life and spirituality. For the longest time, I tried to exempt myself, invoking various reasons and excuses on different occasions. Perhaps I was unconsciously afraid of my inability to adequately describe his spirituality. But in the summer of 1999, as we sat on a beach near Rome, Thuan and I spoke far into the night about his life and his thoughts. He asked me again to consider writing his biography. Although it took a long time before I had the courage to accept the task, I have finally written here of Thuan and his spiritual journey. I hope that those who read this book will learn as much from it as I have from writing it.

Author’s Note

Cardinal Francis Xavier Nguyen Van Thuan passed away on September 16, 2002, a few months after the completion of this biography. In reviewing its content, I see no reason to expand or shorten the story told. The miracle of hope that was his life led him into eternity, serene and obedient to God’s will.

Twice during his terminal illness, he asked me to come to see him at Casa di Cura Pius XI in Rome. In July, we spoke at length about this work and its upcoming publication. In September, when I returned, he was too weak to speak. Even then, I could read in his eyes his wish to see his spirituality live on. I hope that this biography will contribute in a humble way to the understanding of Francis Xavier Nguyen Van Thuan’s vibrant message of hope and unity.

Part One

A Cruel and Enchanting World

I myself will take a sprig from the lofty top of a cedar…I myself will plant it on a high and lofty mountain.

Ezekiel 17:22

Vietnam is your fatherland, a country loved by its children for so many centuries.It gives you pride; it gives you joy; love its mountains, love its rivers….

The Road of Hope, F. X. Nguyen Van Thuan

Chapter One

The Seeds of Faith

Their inheritance [will remain] with their children’s children. Their descendants stand by the covenants; their children also, for their sake.

Sirach 44:11–12

Contemplating, from my childhood, these shining examples, I conceived a dream.

Five Loaves and Two Fish, F. X. Nguyen Van Thuan

Francis Xavier Nguyen Van Thuan was born on April 17, 1928 in the central part of Vietnam, in Phu Cam parish, a suburb of Hue. Hue had long been the capital city of “Imperial Vietnam.” By 1928, however, it was not without some irony that Vietnamese continued to call their ruler “emperor” and the country he ruled an “empire.”

For almost a thousand years, until the early tenth century, the Viet people had lived under Chinese domination. But in A.D. 936, with the beginning of the Vietnamese dynasties, a long line of Vietnamese sovereigns from eight different dynasties succeeded in fighting off Chinese and Mongol invasions. Except for a brief period from A.D. 1414 to A.D. 1427, the Vietnamese managed to preserve national independence until the mid-nineteenth century, and to expand their territory south, away from China in an en masse “March to the South” or Nam Tien.

Despite Vietnam’s self-governance, the Chinese to the north continued to “bestow” the title An Nam Quoc Vuong (King of the Pacified South) upon the Vietnamese rulers. The sovereigns, however, took for themselves the title of emperor when the Chinese Emperor was not looking. Beginning with the Nguyen dynasty, founded in 1802 by Nguyen Anh (Emperor Gia Long), the country was called Dai Nam, rendered “Greater Vietnam,” or more simply, “Vietnam.” But both the ruler’s title and the country’s name were somewhat ridiculous by the time Thuan was born, since Vietnamese rulers were mere figureheads of the French colonial administrators, who had taken the country’s reins in the second half of the nineteenth century.

Although crowned the country’s ruler in 1926, Emperor Bao Dai went to study in Paris as a ward of France. He returned to Vietnam in 1932 to rule only the small, central portion of the country. The southern provinces of the country had become known as Cochinchina and formed a separate French colony; the Northern provinces, known as Tonkin, were nominally under the emperor’s rule, although actually administered by French colonial officials.

This three-part division of Vietnam by the French, whose conquest began in 1858 and ended in 1885, demonstrated their strict political motto: “divide and conquer.” They had dismembered Vietnam and left the Nguyen emperors with little more than symbolic power over the central third of the traditional Viet territory. By the twentieth century, the emperor of Vietnam was no more powerful than the neighboring rulers of the French colonies of Cambodia or Laos—kingdoms that together with the three parts of former Dai Nam made up French Indochina.

To truly understand Thuan, one must keep in mind the profound attachment he felt for his birthplace. Hue was known as the Divine Capital, the seat of the emperor whom the people called the Son of Heaven and considered a god. Vietnam’s capital had changed many times under the various kings and emperors of successive dynasties, yet none of these ancient cities, including the northern city of Hanoi, preserved as much of their past glory as Hue—the only city in Vietnam whose impressive, centuries-old monuments have not been irreparably damaged.

From the heights of Hue’s Phu Cam suburb, one could see the outline of the walls of the Citadel of Hue, and the city’s Flag Monument. By ascending the pine-covered Ngu Binh Mountain, a half mile southwest of Phu Cam, one had a panoramic view of the Perfume River, which flowed through the center of Hue, and of the European City on the river’s right bank and the Imperial City on its left. From that height, at the top of the mountain, the upper parts of various buildings of Hue’s Imperial Palace could be seen emerging from behind a second set of defensive walls and moats. A string of imperial tombs dotted the banks of the Perfume River further south, the farthest away being the tomb of the first Nguyen emperor, Gia Long.

For the natives of Hue, these palaces, monuments, pagodas, and temples added to their city’s natural beauty. Hueans believed that they were born to be poets and artists, and the environment was truly conducive to poetic and artistic aspirations. This native environment exerted a great influence on Thuan, who loved nature, the arts, poetry, and whose refined taste was born of the very air he breathed and water he drank in Hue.

Thuan’s first love was not exclusive, however. Thuan grew to love intensely all the provinces of Central Vietnam, the rugged land where a resilient and passionate people lived, and later, as he traveled through it, all of his country.

When Thuan was born in 1928, Phu Cam was a sparsely populated community with fewer than a hundred houses surrounded by vast gardens and orchards. Its only distinction was that almost all of its residents were Catholics—a miracle since only forty years earlier Catholics were still being persecuted throughout the empire.

For over two centuries, from 1644 to 1888, Vietnamese kings and emperors, ruling princes and their mandarins (who were officials of the imperial administration), as well as misguided scholars (the van than), had lashed out at Catholics. They carried out persecutions sometimes lasting a few years, occasionally for decades, but always fueled by a fear and hatred of the little-understood new religion introduced to Vietnam by sixteenth-century European missionaries. These persecutions, however, were not religiously but politically motivated, for the rulers and the mandarins foresaw that the new Catholic religion would bring cultural, social, and political changes, which would eventually threaten the established order.

Within these official periods of persecution, bloodthirsty mobs, encouraged by the silent consent or whispered prompting of the Vietnamese Imperial Court and mandarins, went on rampages against Christian communities. Thus, Christians were arrested, imprisoned, tortured, and executed by authorities, as well as humiliated, terrorized, and massacred by frenzied mobs.

For 244 years, these persecutions raged, subsided, and then raged again, resulting in a total of 150,000 martyrs: bishops, priests, religious, and lay men and women. More than 3,000 Catholic churches were burned to the ground, entire Christian communities slaughtered, and their homes plundered and torched.

Yet, after the most violent and vicious persecutions under the Emperors Minh Mang (1820–1841) and Tu Duc (1847–1883), Phu Cam parish still stood proudly on the southern hills of the capital city and testified to the resilience of Vietnamese Catholics. For Thuan and his parents, the survival of the parish also testified to the power of their crucified and risen Lord.

The year 1885, with the French military conquest of Vietnam, proved a fateful and disastrous one for both Vietnam and Vietnamese Christians. The French conquest, begun in 1858 with the excuse of intervening in the persecutions, had met with stiff, but ineffective resistance. Though the Vietnamese army fought valiantly, they were no match for France’s “modern” rifles and cannons; one province after another fell to the French advance. The Vietnamese signed treaty after disastrous treaty, which only served to sanction the fait accompli and expand the French hold on the remaining territory.

By 1885 North and South Vietnam were firmly in the hands of the French, although the Vietnamese Imperial Court was permitted tenuous control over North Vietnam. The provinces of Central Vietnam were given the status of a protectorate, which meant that the Vietnamese emperor and his mandarins had power there, although it was extremely limited, and the French continued to gradually reduce the remnants of the emperor’s authority. The emperor still possessed the semblance of a treasury, absolute power within the walls of his palace in Hue, and a small army—weak as it was.

On July 4, 1885, in the face of the arrogance of new demands made by the French, the two regents of the child Emperor Ham Nghi ordered the imperial army to launch an all-out attack on the French garrisons in Hue. It was an unfortunate decision. The poorly planned attack was doomed to fail from the start. The antiquated “gun gods” of the Vietnamese roared throughout the night, with most of the cannonballs flying into the Perfume River. Damage to the French garrisons was negligible. At daybreak, the outcome of the battle was immediately clear even to the most hardheaded of mandarins. Then the French launched a counter attack. The young emperor was hurriedly escorted out of Hue and taken on an exhausting march to the surrounding mountain strongholds. He was finally captured and exiled in 1888.

The mandarins who had accompanied the emperor into the mountains appealed to the village people to fight the French. Overnight, armed bands sprang up all over the country and formed a somewhat cohesive network of resistance against the French. At the same time, the mandarins spread rumors, blaming the recent defeat of the Vietnamese imperial army on Christians. The van than joined in, accusing the Christians of being traitors of the nation; they were the country’s “inner enemies” who had to be exterminated. From 1885 to 1888, the van than militia killed tens of thousands of Catholics.

One night in the autumn of 1885, the people in the village of Dai Phong heard rumors that a van than raid had been planned against the Catholics in their village. Having no time to arm themselves to fight or to take flight, they rushed to the small thatch-roofed church, all the while knowing that they would probably not escape death. Among the Christians gathered in the church that night was most of the family of Ngo Dinh Kha, Thuan’s future grandfather.

As the people prayed, encouraged by their pastor, an armed mob encircled the church. Suddenly flaming torches were thrown onto the roof of the building that quickly caught fire and spread to the mud and bamboo walls. Inside, the chanting of prayers could no longer be heard above the screams of children. Parents frantically tried to save their children by throwing them out of the windows. Most of these unfortunate children were immediately caught by members of the militia and thrown back into the inferno. But some, thanks to the darkness of the night and the billowing screen of smoke, did escape.

One who escaped in this way was Kha’s younger cousin, ten-year-old Lien. “Aunt Lien,” as Kha’s cousin was later known, moved to Phu Cam and lived there until her death in 1938. Children and adults would often come to hear her tell, in simple words, her account of what happened on that terrible night in Dai Phong.

Another who escaped was Kha’s mother, who had been away from the village. Fortunately, Kha had also been away, studying at the seminary in Penang, Malaya (now Malaysia). Due to difficulties in communication, he learned only several months after the tragedy that almost his entire family had been wiped out.

Kha’s teachers at the seminary encouraged him to return home to marry and carry on the family name. While the idea of perpetuating a family’s name was certainly a more traditional Confucian duty than a Christian concept, Kha’s teachers understood its importance. Kha accepted this advice and headed home. He knew that he would have to provide for his ailing mother, now left without any resources.

Much later Ngo Dinh Kha would play an active role in the Imperial Court as a close advisor of Emperor Thanh Thai. He carried out several major functions during his service to the court: he was the Grand Chamberlain (Thi Ve Dai Than) to the emperor, and as such, also the Palace Marshal in charge of protocol, and the Commander of the Imperial Guards. In 1902, the Emperor granted Ngo Dinh Kha the title of Great Scholar Assistant to the Throne (Hiep Ta Dai Hoc Si), actually placing him in the ranks of the court’s permanent ministers. Kha also held the title of Imperial Tutor (Phu Dao Dai Than), making him the emperor’s personal instructor and advisor, especially in the subjects of the French language and Western philosophy. In 1903, the emperor no longer required Kha’s instruction, but allowed him to keep this position and title. Whenever possible, Emperor Thanh Thai would ride to Phu Cam on horseback to enjoy a few hours of relaxation with his old and loyal friend under the pretext of seeking information from the learned man.

Kha represented a very small number of Catholics who achieved some of the highest positions at the Imperial Court. His presence at court, in fact his very life, which had been spared in the great massacre, was a miracle.

Until his death Kha’s mind was constantly haunted by the memory of the holocaust that had consumed the Dai Phong church and his family. His veneration of all the martyred Christians never waned. He permanently displayed on his desk the first edition of Father Alexander de Rhodes’ La Glorieuse Mort d’André, Catechiste de la Cochinchine, qui a versé son sang pour la querelle de Jesus-Christ, en cette nouvelle Eglise (The Glorious Death of Andre, Catechist of Cochinchina, who shed his blood for the cause of Jesus Christ in this new Church), printed in Paris in 1653. In it, Father de Rhodes offered a terrifying eyewitness account of the execution of the first Vietnamese martyr in 1644. Like many Vietnamese Christians of his day, Kha especially venerated the martyr André who had survived savage beatings and stabbing only to finally be beheaded.

Kha’s daughter, Elizabeth Ngo Dinh thi Hiep, grew up listening to Aunt Lien’s story of the night massacre. She marveled at the Dai Phong parishioners’ courage under persecution and was appalled by the ugliness of religious intolerance. Hiep could not have known that a few decades later her own son, Thuan, would become a victim of such intolerance and would spend thirteen years suffering a living martyrdom for his faith.

As a child Thuan himself also had many opportunities to hear Aunt Lien speak of the events in Dai Phong some fifty-two years before his birth. He took pride in being related to martyrs, but could never have imagined that he would one day suffer in his soul and flesh for the cause of Christ, or that the glorious canonization of 117 Vietnamese martyrs in Rome by Pope John Paul II on June 19, 1988, would adversely impact his own imprisonment.

Born into this tradition of Christian pride and resilience and in a land filled with centuries-old memories of persecution and martyrdom, Thuan could later write in his brief and exquisite Five Loaves and Two Fish how “contemplating from my childhood these shining examples, I conceived a dream.” Indeed, from his early childhood, Thuan dreamt about following the footsteps of Vietnamese martyrs and joyfully serving God in the most distressful circumstances. Incredible odds would at times challenge this dream, but the models he contemplated as a child would never fail to urge him on amidst disaster and tragedy; and these examples shone forth on both sides of his family.

Thuan’s father, Nguyen van Am, was a descendant of Christians who had suffered greatly for their faith. Am’s grandfather had become a legend in his own time because of his courage during the persecutions under Emperor Tu Duc. In 1860, Emperor Tu Duc attempted to wipe out Catholicism, but in his reluctance to shed blood, the emperor devised his phan sap (divide and integrate) policy. It was a despicable scheme that violated the most basic principle of Vietnamese society: the sacredness of the family.

Under the phan sap Catholic families were split up; the heads of families and other male adults were taken away to serve as unpaid laborers on farms owned by non-Christians. Non-Christian landowners were expected not to feed their laborers well and that large numbers would either die of starvation or exhaustion, or that this harsh treatment would cause them to renounce their faith. Meanwhile, their wives and children became servants in non- Christian households with the hope that they would forget their faith.

The emperor believed that his policy would eradicate the “imported” religion in a few years, and it might have worked, except for the compassionate and humane treatment of Christians by non-Christians who did not starve their laborers. However, the main reason for its failure was that the Christians endured that period of forced separation and servitude with heroic courage and resilience.

As a child Thuan listened to his father Am describe the horror of the phan sap policy and the pain and suffering his great-grandparents endured when they were forced to separate—his great-grandmother and her younger children were sent into servitude; his great-grandfather, Nguyen van Danh, worked as an unpaid laborer. Am told his son that it was thanks to Am’s grandfather Nguyen van Vong that his great-grandfather Danh managed to survive.

Vong had been separated from both his parents and worked on a rice field some six miles away from his father, Danh. Somehow, Vong heard of the terrible conditions his father suffered under his cruel landlord. When Vong learned that his father was being starved, the young boy of fourteen approached his own landlord and asked permission to bring food to his father every morning. Vong did not stop to consider that he hardly received enough food to eat himself. Every morning, while it was still dark, Vong woke up, cooked his small ration of food, and carried half of it to his father. He had to run the twelve miles back and forth to be in the rice field on time to begin work alongside the other laborers at sunrise. He did this for several years.

Eventually the emperor realized the uselessness of phan sap policy and abandoned it altogether. Nothing seemed to break the courage of the Christians, and a growing number of non-Christians sympathized with and showed mercy toward the Christians, sometimes even at the risk of antagonizing the local mandarins.

When Nguyen van Danh, sick and emaciated, was at last reunited with his family, he was proud that none of his children had renounced their faith and that his wife had steadfastly continued to teach their children to fear God and love their neighbor. He also proudly admitted that he owed his survival to his eldest son. Not only had Vong brought him food every day, but the boy had also encouraged his father. Danh said that his son’s indomitable courage had made his hell endurable.

Eventually Vong married Tong thi Tai, a close relative of Paul Tong Viet Buong, a military commander martyred under Emperor Minh Mang on October 23, 1833. Buong was beatified by Pope Leo XIII on May 27, 1900, and canonized by Pope John Paul II on June 19, 1988.

The young couple moved to Phu Cam where they met Father Joseph Eugéne Allys, the future bishop of Hue. Father Allys recruited Vong as a unique kind of missionary. He was not to preach, but to settle in a small village, live the life of a virtuous Christian, and convert others through his example. Once there were enough converts in a village, he was to move on to a new village. This novel evangelization technique took Vong from village to village in a region located more than forty miles south of Hue.

Vong, Thuan’s future great-grandfather, spent fifteen years evangelizing in this way. He was so enthusiastic that he would have spent his entire life as a missionary had not Father Allys asked him to return to Phu Cam to spend more time with his extended family.

Father Allys lent Vong some money to establish a farm and he became a prosperous farmer, the chairman of the parish council, and one of the most honored men in the Christian community of Hue. Later, Vong became a builder and constructed the landmark Pellerin Institute for the Brothers of Christian Schools and the Joan of Arc Institute for the Sisters of Saint Paul of Chartres, both inaugurated in 1904. These two institutions attracted elite students from Hue and all over the country. Vong and his son Dieu left their architectural imprint on the major public, religious, and private buildings of the city. They also did the maintenance and renovation work on most of the city’s ancient monuments.

Thuan would never forget all that his family had endured, that he descended from martyrs. Later, when he suffered in his own flesh and soul for the Christian faith during thirteen years of detention, he would recall hearing about the martyrdom of his forefathers ever since he was a child. Strengthened by this example, he would embrace his own “martyrdom” as a cherished heritage. Thuan would venerate his ancestors, along with all the Vietnamese martyrs, until the day he died.

Chapter Two

A Vocation of Patriotism

The LORD has make known his victory; he has revealed his vindication in the sight of the nations.He has remembered his steadfast love and faithfulness to the house of Israel.

Psalm 98:2–3

My mother taught me stories from the bible every night, she told me stories of our martyrs, especially of our ancestors. She taught me love of my country.

Testimony of Hope, F. X. Nguyen Van Thuan

In Phu Cam, Ngo Dinh Kha and his wife, Pham thi Than, had six sons: Khoi, Thuc, Diem, Nhu, Luyen, and Can; and three daughters: Giao, Hiep, and Hoang. Elizabeth Ngo Dinh thi Hiep, born on May 5, 1903, was Kha’s fifth child. Without a doubt, she was the apple of her father’s eye. Among his children, she was the only one who had no fear of him and who dared to take hold of his hand and ask him questions when he was tense or irritable. Even as a little child she was the only one who knew how to appease his anger and soothe his anxiety.

Amazingly, Kha took her into his confidence when she was as young as five. He told her everything and shared his innermost thoughts with her. To his own amazement, Kha heard himself speaking with her about his fears and hopes for Vietnam and of the complicated intrigues of the Imperial Court.

Hiep was allowed to listen as her father engaged in important political discussions. During a particular crisis, Emperor Thanh Thai, whom Kha loyally served, incurred the wrath of representatives of the French colonial administration and was about to be forced to abdicate. Kha stood by the emperor to the bitter end and, by doing so, made many enemies among his colleagues who had abandoned their sovereign. During this time, Kha lived in a state of continual tension and was uncommunicative at home. Yet, to the surprise of her mother and siblings, Hiep could still make her father talk and laugh.

Throughout the crisis Hiep heard most of Kha’s grave discussions with Minister Nguyen Huu Bai, the future Duke of Phuoc Mon, concerning the emperor. Although a quiet child and a good listener, Hiep certainly could not comprehend everything her father and his powerful friend discussed. She was only a guest in that strange world of adults. She did not understand its rules, but she did understand why her father and Minister Nguyen Huu Bai had to fight for the emperor and battle the arrogance of the French officials in the colonial administration. After the two men concluded their meetings, Hiep’s questions seemed to inspire rather than irritate the Grand Chamberlain. He would patiently explain why he and Bai took this or that measure to counter the intrigues of other mandarins who sided with the French and spied on the emperor.

When it became clear that there was no way to save Emperor Thanh Thai from being dethroned, the two friends decided that Bai would remain “loyal” to the Imperial Court and that Kha, instead, would fight against the French for the emperor’s political sovereignty to the end. Ultimately, Ngo Dinh Kha, the only high ranking mandarin to openly oppose the French, was stripped of all ranks and honors and the French threatened to send him back to his grandfather’s village of Dai Phong. Bai, however, managed to persuade the French to allow Kha to remain in Phu Cam, although he would have no further influence at the Imperial Court.

Kha began working a rice field in Phu Cam with his sons. Hiep helped her mother to carry food and tea to the field for her father and brothers. These were difficult years, but no one in the family complained about the dramatic reversal of fortune. During those years of poverty, Hiep continued to live in rapt admiration of her father’s fortitude and patriotism. Kha was moved to tears at times as he watched his little girl courageously going about her chores with a cheerful smile.

Over time Kha prospered as a farmer, but the years of hard work and deprivation would never be forgotten. His sons, who would become important mandarins, had learned the value of manual labor and thrift; they had learned to value loyalty over honors and rank.

Kha’s third son, Ngo Dinh Diem, who later became the first president of the Republic of Vietnam, would proudly recount how he and his brothers had worked hard as farmers. Western journalists and diplomats were required to sit and listen to Diem’s long narratives detailing how he and his brothers plowed and irrigated the fields, how they worked on holidays and on school days, and how poor they were. Not everyone would appreciate Diem’s pride in those lean years, thinking he was merely indulging in nostalgia. But Diem was constantly drawing fresh lessons from the joy, the pain, and the value of hard work his family experienced during those years.

Ngo Dinh Kha and his family were far from common farmers, however. Politics was their true vocation and patriotism their drive. After the French sent Emperor Thanh Thai and his son, Emperor Duy Tan, into exile off the coast of Africa in 1916, Ngo Dinh Kha and Minister Nguyen Huu Bai would spend the rest of their lives fighting for Vietnam’s autonomy. This aim was Kha’s sole ambition. He taught his children to love their country with passion, and hoped that one of them would one day lead Vietnam. Probably around the year 1912, Kha began to place his greatest hopes in Diem.

Diem was only twelve when his father, Kha, and godfather, Bai, began preparing the boy for the possible role of national leader. Kha and Bai spent a tremendous amount of time instructing Diem in everything they knew and in motivating him to model himself on the virtuous leaders of the past and present. Diem was not a docile student. Headstrong by nature, he constantly questioned what he was told until convinced of its truth.

In turn Hiep studied her brother carefully and came to know all of his strengths and weaknesses. Though Diem was two years her senior, he always turned to her when he faced critical problems and, despite her reticence, continued to do so when he become a national leader, the prime minister, and president. Diem had unshakable trust in his sister.

Until he neared his death in 1925, Ngo Dinh Kha counseled his sons to be prepared to fight for their country’s autonomy, though he insisted that it should be a non-violent struggle and the fruit of political negotiations.

On his deathbed, however, Kha no longer spoke to his children of Vietnam’s autonomy. He realized how mistaken he and Bai had been in trying to groom emperor after emperor to wrestle back through negotiations some semblance of national sovereignty once Thanh Thai had been exiled. They had also been mistaken in preparing Diem to fight for their country’s autonomy. Rather, the only goal possible was Vietnam’s total independence.

The emperors Kha served had been either too impatient or too passive, characteristics that had led to one political disaster after another. Ultimately, none of them had succeeded in wresting any colonial prerogatives from the French. Kha knew that even with all his strengths Diem would not succeed in negotiations with the French. If peaceful negotiations could not work, his children must be prepared for even an armed struggle to liberate their country. All of Kha’s children kept his last wish for an independent Vietnam uppermost in their minds. They would both live and die for that dream.

As he neared his death, Kha bound Hiep irrevocably to the political fortune of the Ngo Dinh family. When the moment arrived for Kha to give the father’s traditional parting blessing, he surprised the entire family; he did not ask his eldest son Khoi to step forward; he did not ask Diem. In a gesture heavy with consequences, he called for Hiep to receive the blessing. Kha told the family members gathered at his bedside that from then on Hiep would speak in his name on the yearly anniversary of his death. It was her duty to tell each of them where they had done right and where wrong. He said, “It is only natural that Hiep, who listened to me so well in my life, should speak in my name when I am gone.”

The profound significance of the event was clear to all of them. Among the siblings, Hiep, the faithful listener of their father’s ramblings and musings, possessed the greatest insight into their father’s thoughts and dreams and, therefore, could rightly speak in his name.

Hiep thus became the most valuable resource for her brothers and sisters when they were in doubt. Whatever positions of political importance her brothers held—president, prime minister, governor, presidential advisor—on the occasions when Hiep addressed the family, they listened with bowed heads and invariably thanked her for her strong and reproving words. The annual ritual on their father’s anniversary of death continued until, through a series of tragic events, all of Kha’s sons were killed or forced into exile.

After Kha’s death, his friend Nguyen Huu Bai also took Hiep into his confidence and respected her views and advice. “When I am listening to her,” he once told Diem, “I seem to hear your father’s voice.”

Later Thuan would sometimes speak of his family’s “political spirituality,” which he shared particularly with Hiep and Diem. For his family it was a given that Christians made God’s will the foundation of their political thought and action. Thuan had simply to look back on the living experience of his family to support this view. All Ngo Dinh Kha’s children strongly believed that their dedication to the liberation of Vietnam and the welfare of its people was God’s will. Their sense of justice, their righteousness, their humanity and heroism would make them some of the most tragic and misunderstood yet exalted figures of Vietnam’s modern history.

In particular, Ngo Dinh Diem, a man who lived and died for his political spirituality, was a man of great contradictions. Diem, a meditative man by nature, was pulled into action by a government that needed direction. A naturally mild and kind man, he was placed in a leadership role at moments when the political and military situations in Vietnam were most violent. He took vows as a Catholic monk, but also embraced Confucianism, and at the same time, accepted the demanding position of president of a nation during uncertain times. Diem lived all these contradictions, and his spirituality gave him the courage to do every day what he believed to be right. Few Christian politicians could have shown Thuan a better approach to political spirituality than his uncle.

Intense as their dream for the independence of their country was, Kha’s children did not forget their first duty: the practice of their Christian faith. Kha himself had lived a devout Christian life and spent an exceptional amount of time in daily prayer and meditation. From his home’s terrace that overlooked the Phu Cam Cathedral, he loved to listen to the clear, musical rhythm of the parishioners chanting morning and evening prayer.

The Ngo Dinh family would walk briskly across the street to the cathedral for Mass, and while he might speak with his children on the way, once inside Kha became completely unaware of them. The children watched in awe as their father prayed and became so absorbed in the presence of God that he seemed to enter a kind of trance.

Kha’s children would learn to pray with similar attention and devotion, especially Diem and Hiep. Both were mystics in the sense that through their prayer and penance, they constantly felt God’s presence within and around them. Like their father, they often became oblivious to the world around them when praying.

Pham thi Than was less educated than her husband, but she took very seriously her role as her children’s first educator. She admonished them when they failed to answer correctly their catechism questions. With her, the children studied their faith and memorized the contents of their catechism text, written by the French missionaries.