Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

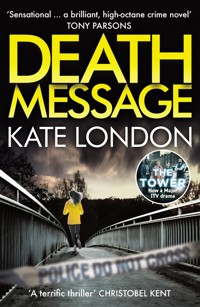

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

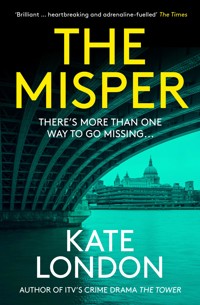

From the author of ITV's THE TOWER 'Rips along like a rattlesnake. Absorbing. Relevant. Tense.' Imran Mahmood There's more than one way to go missing... When Ryan Kennedy is imprisoned after killing a police officer, he knows what he has to do. Keep his mouth shut about who he was working for, keep his head down, and rely on his youth to keep his sentence short. When he gets out, he'll be looked after. Following the death in the line of duty of a fellow detective, DI Sarah Collins has left the capital for a quieter life in the countryside. But when a missing teenager turns up on her patch, she finds herself drawn into a much bigger investigation - one that leads her right back to London, back to the Met, and back to Ryan Kennedy, the kid who killed a cop. This powerful novel from a former Met detective explores the devastation that organized drug-running gangs can wreak on young lives. It asks who deserves to be saved - and whether saving them is even possible...

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 429

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Sammlungen

Ähnliche

Kate London graduated from Cambridge University and worked in theatre until 2006 when she joined the Metropolitan police service. She finished her career working as part of a Major Investigation Team on the Metropolitan Police Service's Homicide Command. She has since written four novels in The Tower series, which is now a major ITV drama, starring Gemma Whelan.

Find out more by following her on Facebook and Twitter @K8London.

The Tower series

The Tower (previously published as Post Mortem)

Death Message

Gallowstree Lane

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2023 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

This paperback edition published in 2024 by Corvus

Copyright © Kate London, 2023

The moral right of Kate London to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978 1 83895 451 2

E-book ISBN: 978 1 83895 450 5

Printed in Great Britain

Corvus

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

To my mother.

PROLOGUE

1

It was a boy he knew a bit from school who made the connection. It was when Leif was suspended. Jaydn was two years older and he was wavy. He had all the stuff, the trainers, the jacket, but it wasn’t just the garms that made Jaydn cool. Whatever that other thing was that made you cool, that deep thing; he had that. At first, they were just smoking weed. Then Leif met Mo, who was kind of dirty, but he let you hang at his place. Jaydn said, ‘You could do this. You do as much or as little as you want. Your mum can’t tell you anything.’ That was during the time his mum had taken his PlayStation away. Jaydn said, ‘You can make money and any money you make is yours.’ He gave Leif a phone and a weed crusher. ‘Just a little something,’ he said. ‘Hey, man, believe.’ Then he said, ‘You know I gave you this, you do something for me?’

That’s how Leif started running with the Bluds.

PART ONE

THE INCIDENT

2

The gun springs back in his hand and Ryan thinks, Wow, I didn’t shoot myself. But, in almost the same instant that he has this thought his eyes communicate to his oh-so-slow brain that the guy in front of him has jerked backwards, as if pulled suddenly by a hawser attached to his back. The bang almost deafens the exhalation the man makes. But the exhalation is definitely there. You’ve shot him, he thinks. That’s crazy. Things are moving both super-fast and very slowly at the same time. How is that possible? And the look on the man’s face. No one could be more surprised than he is! One minute so cool and in control, using big words, and calming him down, the next, well, not so cool. It’s nothing like the telly. No holding your hand to your chest. No big speeches. The man falls onto the floor and sort of gurgles.

Ryan stands for a second with the machine in his hand. In the next instant there’s a blast downstairs. Steve says, ‘Throw the gun away or they’ll shoot you.’ Feet hammer up the stairs. Ryan throws the gun into the corner of the room just as a man appears in the doorway. Helmet. Balaclava. Ballistics vest. Armed police, don’t resist! No chance of that; the room is full of them. The whole thing has been a dream, or this is a dream; his brain is struggling to catch up, to seize an understanding of what is happening, while the other Ryan, the physical Ryan, is swept away. A tornado has got hold of him and lifted him into the air and then thrown him on his front, face down on the floor, guns pointed at his head, hands in cuffs behind his back. It doesn’t even hurt. The main thing is astonishment because even though it’s all clearly been some sort of massive illusion, he still can’t work out what the illusion actually is.

Can’t see much but black boots. Although he’s shot someone, he’s surprisingly irrelevant; no more than the subject of a kind of packaging service. It’s Feds Amazon! Black boots everywhere. There must be loads and loads and loads of them. He’s pulled to his feet and put to stand with his back to the mantelpiece. The snitch, whose fault this all is, Steve, stands beside him. Out of the corner of Ryan’s eye he sees that Steve has blood on his hands, his face, his chest. Hopefully that’s from the guy on the floor. He can’t have shot him as well, can he? They don’t look each other in the face. They stand and watch what is unfolding in the room. Ryan thinks, Even though I’ve actually shot someone, it’s not about me. There seems to be some information there about his whole existence. Any case, the most important thing is, without a doubt, the guy on the floor. Turns out the black boots weren’t just police. There are lots of medics in green with their dead bags, and side pockets and heavy stuff that must do something important. Screens and tubes and canisters. They are crowding around the guy and every single one of them looks busy. The guy’s a fed, for fuck’s sake. Kieran, he said his name was. And just about a minute ago he was promising Ryan could get off lightly. That having the gun, and holding Steve prisoner, wasn’t so bad, all things considered, but murder was, so better steer clear of that one. And now the guy who told him to steer clear of murder is lying on the floor surrounded by medics because Ryan’s shot him. What a joke. For another stupid second Ryan thinks, Mum will kill me. The window is shattered – when did that happen? What remains of the panes of glass are splashed with blood too. The whole room is like someone’s been throwing cans of red paint. There’s a woman. He recognises her. Lizzie, that’s it. She arrested him about one hundred thousand years ago. She’s crying and trying to get close to the man on the floor and the man says, ‘Let her come.’ And she says, ‘You’re going to be all right.’ So, it’s calm after all. It was an accident, and like the woman said – Lizzie – the guy’s going to be all right. But for all that the medics are very busy. There’s dressings and shit all over the floor and the thump thump thump of helicopter blades.

That was what he thought then, but it turned out that wasn’t even the half of it. Because his lawyer told him when they talked in the police station – Ryan in a white paper suit – that Steve wasn’t a snitch. He was a fed too. An undercover officer. Like in a film. And the man he shot? Detective Inspector Kieran Shaw? He died.

At the magistrates’ court, he’s remanded. The lawyer warned him that would happen. It’s standard, he said, as though that made it better. For a murder charge, he said. Standard. Don’t worry, he said, it’s just the beginning.

Oh, thanks, man. Yeah, great.

It’s SERCO now, not police. Out of the court in handcuffs, up three steps to the door at the side of the truck. Then into one of the compartments. Three feet wide, three feet deep, just big enough to hold a man. A hard moulded seat facing forwards. He sits. The guard locks the door. He expects them to drive away but nothing happens. How come they call these things sweatboxes? It’s freezing. More packaging. He’s an Amazon delivery again, not a human, and he’s stuck in here with his thoughts.

Other people. The doors of another compartment opening. He stands and looks through the darkened pane of the small window. He can see the yard of the court. People moving around. What it’s like to be free. Then a voice from inside the truck.

‘Oy, you the cop killer?’

Even in this little box with its darkened window he already has a sense of how important it is to be respected by the people he is confined with. It is vital to say the right thing. He has to learn quickly. But his lawyer said, Don’t talk to anyone. Anyone can witness against you.

Another voice. ‘It is. I saw him. Ryan Kennedy.’

Suddenly the truck is full of voices.

‘Killing a fed, Ryan. Well done, bruv.’

‘Murder, that’s life. Minimum twenty years.’

‘Killing a cop? He’ll get whole life for that. Never get outside again.’

Then there’s the joker.

‘You innocent, Ryan? Just like Andy Dufresne in Shawshank.’ The voice does a passable Morgan Freeman imitation. ‘You gonna fit right in.’

Ryan pulls his feet up onto the seat and wraps his arms tightly round himself.

And they’re off. The van surges. He steadies himself on the bulkhead. Pulling out of the gates there are flashes at the window. ‘That’s for you, Ryan. You’re famous!’ He stands up and immediately there’s a bright flash through the dark glass. They’ve got him. It’s gonna be everywhere. His poor mum. His sister.

I’m a celebrity, he thinks. Get me out of here.

Out into London’s streets. Simple things, seen through the frame of the small square of glass. It’s like a boring film on Channel 4 that normally you’d bin in five but which has suddenly become completely engrossing. A boy on a bike. An old man with a dog. A park with a playground empty except for three youngers hanging out on the swings smoking weed. The van pauses like a labouring beast then swings heavily left onto the main road that runs along the edges of the Deakin. The concrete line of home spools out. The ramparts and walls. The walkway where he and Spence stood as kids looking down on the chuntering tube trains. The meadow that the newcomers planted with flowers. They used to go there and lie on their backs and smoke weed. The Deakin will carry on without him and Spence. Spence is under the earth. Ryan may never get back there.

‘You been in prison before, cop killer?’

‘You wait,’ another voice shouts. ‘Prison smells like a junkie’s arse.’

The smell hits him as soon as he enters the prison and wraps itself round him as he walks along the landing to his cell carrying the bag of stuff his mother brought to the court for him.

He understands at once what the smell is: it is the sweaty fearful molecules of boys confined. Boys eating, shitting, wanking and staring at the ceiling in a cramped space with a window that doesn’t open.

The door is unlocked but he stands on the threshold for an instant.

‘In you go, son.’

He steps inside and the pain of the door locking behind him is a little explosion under his chest. He puts the bag on the floor and presses his hands against his face.

He tells himself he’s on remand. Not guilty yet. Not yet. He can still wear his own clothes and they are endlessly precious to him these sweatshirts and trousers and socks and T-shirts. He sits on the bed and sticks his face in the bag and smells his mother’s washing powder.

He takes one of the T-shirts out, leans forward and opens the locker. Inside, on the top shelf, is a brand-new pair of black Balenciaga trainers. Five hundred quid’s worth. He shuts the door. He opens it. They are still there. What the fuck? He holds them in his two hands and is afraid.

He’s only been in three days. They are on something called the red regime. Not enough staff so just one hour for exercise. Standing in the yard thinking how he can’t even see the sky properly. How long before he will see it unconfined again. How long before he can take a shower whenever he wants one. How long before he can get on a bike.

One of the lads told him there was a sweepstake on his sentence running. ‘Killing a fed. You could get whole life for that. Never get outside again.’

He hasn’t even been found guilty yet. Aren’t there any odds running on that?

None of his usual stuff works. He can’t imagine his life as a professional footballer because the walls press on him and, instead of the daydream, into his mind comes reality. He can’t get up and go out. He can’t take his ball and kick it about with his friend.

He is shut in with a preoccupation. They asked him about that when they booked him in.

‘Any thoughts of self-harming?’

All the time.

‘No, boss.’

Not so easy, in any case. They have him on a watch to stop that. At night the screws open the hatch on the window and shine a light in on him. Every hour. ‘You still with us, Ryan?’

They have an hour for socialisation but down the corridor it is kicking off. The alarm sounds. Ryan gets up and moves to the doorway of his cell. A youth, big like a door, stands outside.

He nods for Ryan to move back into his cell. Ryan wonders whether he should try to get past him, but that’s impossible. He steps back. The youth says, ‘Got something for you.’

He pulls something out of his pocket. It is a tiny phone and a piece of paper with a phone number.

‘Dial that number and eat the paper. Screws will get this shut down pretty quick. I’m outside.’

Ryan sits on the bed, the little window above him, the picture of his mum and his sister in its frame on the table.

The phone only rings once before it is picked up. The voice is deep, distorted, monstrous. What the hell is going on?

‘The Federation has taught you that conflict should not exist. But without struggle you would not know who you truly are . . . Struggle made us strong.’

‘Who is this?’

Laughter.

‘It’s Krall. Former Starfleet captain.’

Then he knows who it is. Shakiel. What a doughnut.

‘You got what I sent you, fam?’

‘The trainers was from you?’

‘Who else? Bluds still got you.’

Ryan doesn’t answer. They are in his cupboard. He hasn’t dared wear them.

‘Listen, Ry, what you did. It was good. Don’t worry about it. It’s like the man says. There are things that have to be done and you do them. You just do them. Then you forget it.’

‘What man, Shaks?’

Laughter. ‘The man, Ry, the man. The Godfather.’

That’s the voice, the voice he’s done so much to please. The voice he’s wanted so much to turn its attention on him. Now he is afraid of its focus. He feels the pressure, reaching him as if there are tentacles winding their way through drains and cable lines and stretching into his cell. He’s locked away here but Shakiel can get to him if he wants to. The fighting down the corridor – all that so he can have this little chat?

‘Don’t worry about the time, Ry. I’ve got guys in there gonna look out for you. Like I said, you’re family.’

But nothing comes free. Ryan knows that.

‘I’m getting off most of it,’ Shakiel says. ‘Gonna be out in about ten, I reckon.’

Ten. Ten years. How can anyone do ten? And Ryan’s looking at a lot longer. He can only catch glimpses of the sky. He wants to be able to get on his bike and ride. Just that one thing. He would give five years of his life for that. On the first night one of the boys sharpened the plastic casing of a biro. Stuck it in a milk carton. All night he was cutting himself with it. Lot of blood, the boys said, but no real harm.

‘Grenades was dummies,’ Shakiel says. ‘Who’d a thought I’d be pleased about that?’

‘What about Lexi?’

‘Lexi? They’ve dropped that. Course they have. Nothing to link me.’

‘And Jarral?’

‘Jarral can’t duck it but he can hope for something else. Death by dangerous driving, his lawyer is saying. Or manslaughter.’

‘Jarral’s not snitching, then? My lawyer said he was. Going Queen’s.’

‘Shh, Ry. What would he talk about anyway? Like I said, nothing to link me to Lexi.’

Ryan sits on the bed and draws his teeth down his top lip.

Shakiel says, ‘Any case, Jarral’s not a snitch.’

There it is. That’s what this is all about. Shakiel doesn’t even need to tell him not to say who gave him the gun.

‘You happy with your lawyer? You know I can help with that.’

A lawyer reporting straight to Shaks? No thanks.

‘No, but listen, thanks for the offer. You’re all right. My lawyer’s sound.’

‘So, what’s your plan? What you gonna do? What you gonna say?’

‘I dunno. Still trying to work it out.’

‘OK, but roughly.’

‘The lawyer says plead to the gun, plead to the lesser stuff, but fight the murder charge.’

‘That sounds good.’

Course it does. Plead to the gun. Then you won’t have to say who give it you.

He should say something but he can’t speak. Any case, Shakiel’s doing all the talking. He’s never talked so much. He says, ‘Your mum. Is everything blessed at home?’

‘I guess.’

‘And your sister. What’s her name?’

‘Don’t say her name, Shaks. I know you know her name.’

‘OK. OK, Ryan. Don’t be thinking bad thoughts. I’m just gonna make sure they’re looked after.’

Looked after.

‘My man, who handed you the phone, he’s gonna look out for you. They move him, there’ll be someone else.’

The cell feels so small. He wants to pour his heart out, say, Life, Shakiel, they’re talking life. Tell him about the sweepstake running on how much time he’s got to do. Twenty years would be short, everyone’s saying. You killed a fed, what do you expect? Twenty? He’d be thirty-five. Thirty-five! All his youth wanked out in a tiny room. But he’s got to bury all this deep. There’s no place or time left to cry about it.

Shakiel says, ‘What did I say?’

‘I dunno.’

‘There are things that have to be done and you do them. Then you forget it. Who said that?’

‘The man.’

‘That’s right. The man, Ryan. Which man?’

‘The Godfather.’

‘You got that?’

‘I got that. Thanks, Shakiel. Appreciate it.’

‘Gotta go. Hold your head up. You did well. All you got to do, Ry, is what you always gotta do: learn to firm it.’

The line goes dead. The big guy steps back in and holds his hand out. Ryan gives him the phone.

‘Yeah. Safe,’ the guy says. ‘I’m Costello. Gonna be looking out for you.’

Then he’s gone. Looking out for you. There’s been a lot of talk of looking out. Could mean one thing, could mean another. That’s the beauty of it.

Ryan lies back and stares at the ceiling. What the lawyer really says is that he should apply for the National Referral Mechanism; go to the judge, say he’s been groomed. He was fifteen when it happened: a victim, not a perpetrator. But he can’t do that. Whatever the sentence he won’t dodge prison, not after he’s killed a police officer. So, he can’t go live somewhere Shakiel can’t reach him. He’s got to do that thing Shakiel told him: firm it. And then there’s that other thing Shakiel’s told him to do, which was to forget it.

PART TWO

R V KENNEDY

3

On the pavement outside the Bailey the camera crews are massing. DC Steve Bradshaw steps onto the road to avoid them as he makes his way towards the court’s lesser-known entrances. In the trial of R versus Ryan Kennedy he has been given anonymity; he will be known to the court as Officer V23, and his evidence will be given from behind a screen. Nevertheless, as he shows his warrant card and slips into the building, he feels a kind of nausea at what is about to unfold and into his mind comes a wildlife documentary he once half-watched, eating his dinner in front of the telly.

The light had glinted greenish gold off the scales of the bigger, slower fish as they began to pick off the littler ones. The pulse of the music quickened. One of them, dead-eyed, had a smaller fish in its mouth, the tail still flapping. A low, curiously thrilled, BBC voice narrated and it was this curious thrill, he thinks, that had so nauseated him.

‘Waiting in the wings, to pick off any injured fish, are the piranhas.’

He imagines his words followed by such a feeding frenzy, his experience gobbled up. What do they have nowadays, these people who live on their phones? Hashtags and trends and memes.

Transcript: Examination in chief of undercover officer V23 in the trial of R v K

(The defendant cannot be named for legal reasons.)

Q: Officer V23, you had been working undercover on Operation Perseus for a couple of years at the time of Detective Inspector Kieran Shaw’s death.

A: Yes.

Q: You had infiltrated yourself into the community where the Eardsley Bluds, an urban street gang, are based?

A: They are a lot more than an urban street gang—

Q: Please, confine yourself to answering the questions.

A: I had developed a cover over two years.

Q: And Ryan, the fifteen-year-old who fired the shot that killed Detective Inspector Kieran Shaw, what part did he play in this process of developing your cover?

A: The targets of Operation Perseus were the leaders of the Bluds, most importantly Shakiel Oliver, and the European gang that were supplying them with firearms. It was an organised crime network—

Q: As I said, please limit yourself to answering my questions.

A: Ryan was not a target for us. He was someone who happened to come into the orbit of the operation because he was close to Shakiel Oliver.

Q: Very well.

A: Ryan was what drug dealers call a roadman.

Q: A roadman. Explain your understanding of that word.

A: A roadman is a young person – usually a boy, but sometimes a girl – who spends a lot of time on the streets. He’s kind of a runner, delivering drugs, getting into all sorts of trouble, in Ryan’s case committing robberies too, that kind of thing.

Q: So how would you describe Ryan’s relationship to the Bluds?

A: He was on the edges. I can’t be more precise than that. It’s not as if the Bluds have got membership cards and ranks. They can’t be identified and called to account. They’re not like us. They’re not the police.

Q: Thank you for that, Officer.

A: I’m explaining the real-life difficulty we faced. It’s hard to assess precisely the status of someone like Ryan. He was a hanger-on. Someone who was maybe looking for more involvement, or someone who might in the course of things drop out and have no further criminal involvement. But he was not one of our targets.

Q: The jury have been given transcripts of recordings made by you over the period of the operation. Based on those transcripts, can you tell me how much time you spent with Ryan?

A: A hundred and seventy-six hours, but that’s over a period of two years. Two hours a week.

Q: I’m sure the jury can do their own maths.

A: If you say so.

Q: In any case, the time doesn’t average out over two years. In the first year, how often did you meet Ryan?

A: Five times.

Q: And who else was present at these meetings during the first year?

A: Shakiel Oliver, Ujal Jarral, other people whose names I did not always know.

Q: And where did you meet?

A: Clubs. Pubs. Once in a betting shop.

Q: Whereas in the last nine months you met how often?

A: I don’t have that figure to hand.

Q: Look at the schedule. Take your time.

A: OK, so . . . thirty-seven times.

Q: In the three weeks before Shaw died, how often did you meet?

A: Eight times.

Q: And where were most of your meetings in those last three weeks?

A: In the flat.

Q: The flat?

A: The flat the operation had rented for me to live in.

Q: And who else was present at those meetings in the flat?

A: It was the two of us. Ryan and me.

Q: The last three meetings? How long did they last?

A: The first lasted two hours, the second two and a half, the third an hour and a half.

Q: And why did you, a highly trained undercover police officer, choose to spend so much time one-to-one with someone who wasn’t even a fully-fledged member of the Eardsley Bluds? With someone who, as you just said, was no more than a roadman? Just fifteen years old and a hanger-on?

A: I didn’t choose. We can’t choose who comes to us. We are in the business of infiltrating a community. Ryan was close to Shakiel Oliver and he made himself available.

Q: And do you know why he ‘made himself available’, as you say?

A: I can’t say. I’d infiltrated the Bluds. Shakiel knew me. Jarral knew me. From time to time, Ryan came to me with things he had stolen. He thought I was a fence.

Q: Ryan came to you when his friend, Spencer Cardoso, was murdered.

A: He came to me because he had stolen a phone. He wanted money for it.

Q: How had you assessed whether that stolen phone wasn’t a pretext for a boy who was in great distress?

A: I refer you to real life. I was undercover. Ryan came to my door and told me he had stolen a phone and he asked me to fence it. The phone was subsequently traced to a robbery. My job was to maintain my cover and to gather intelligence. I offered him money for the phone.

Q: I refer you to the transcript of your conversation when Ryan brings the stolen phone to you. This transcript was exhibited by you and is in the jury bundle {SB7478/5}. The defendant enters the flat. You offer him a drink of Coke. Please tell me what you say to him at line three.

A: I say, ‘You all right?’ A normal thing to say to a person.

Q: Thank you.

A: And he replies, ‘Yeah.’ Also normal.

Q: What do you say at line five?

A: I say, ‘Only you sounded like you were going to break the door down.’

Q: ‘You sounded like you were going to break the door down.’ Then at line twelve you say?

A: ‘Cheese and Branston, mate?’

Q: Why do you say this?

A: Because I was making him a cheese and Branston sandwich.

Q: Can you tell the court anything else that you offered him.

A: I give him crisps and cigarettes.

A: You say? Line twenty-three?

A: ‘Help yourself, mate.’

Q: Then, at line thirty-seven, he starts to tell you what?

A: That he was there when Spencer Cardoso was murdered.

Q: What was Spencer Cardoso to the defendant?

A: They dealt drugs together.

Q: Officer, please read line fifty-seven of the transcript that you signed as a fair record.

A: It says that Ryan Kennedy is sobbing and that I am rubbing his back.

Q: And at line sixty, you say?

A: I say, ‘You’re all right, mate. You’re all right.’

Q: Mr Kennedy replies?

A: Spence, he was so frightened and he didn’t know what was happening and then he sort of lay down.’

Q: To which you say?

A: ‘Mate.’

Q: Then Mr Kennedy tells you what?

A: That he has gone to Shakiel and told him that they have to do something about it.

Q: Specifically, he says, line sixty-four, please, Officer.

A: ‘We have to do something about this, pay them back.’

Q: Pay them back.

A: I immediately told my superior officer about this disclosure.

Q: That was not the question.

A: What was the question?

Q: We’re getting to it. It’s clear from your own transcript that Ryan confided in you and that you did everything you could to encourage him to trust you. You must have known that he was on the edge. How did you mitigate this risk?

A: It was my job to infiltrate the Bluds and Ryan made himself available. He was involved in criminal activity and he sought me out because he believed I was too. His contact with Operation Perseus had been overseen by higher ranking officers than me. He had information. What was I to do? Blow my cover? Tell him to go away?

Q: You made him very welcome. You made him a cheese and Branston sandwich. You rubbed his back and called him ‘mate’.

A: I did my job. Nobody asked him to come to me and offer me stolen goods.

Q: What did you know of Ryan’s home circumstances?

A: He lived with his mother and sister.

Q: Where was his father?

A: Dead.

Q: Was that all you knew about his father?

A: He had been murdered, when Ryan was three.

Q: How long had Ryan known Shakiel Oliver?

A: Since he was a child.

Q: Why was that?

A: I believe because his father and Shakiel had been friends, criminal associates probably.

Q: Do you know they were criminal associates, or are you assuming that?

A: I have no evidence that I can put in front of the court that they were criminal associates.

Q: How did it affect your relationship with Ryan that his father had been murdered when he was an infant?

A: I don’t understand what you’re asking me.

Q: By your evidence Ryan was vulnerable. His father had been murdered and he was close to a dangerous man, Shakiel Oliver. Ryan had told you that he was looking for vengeance for the murder of his friend. How did you execute your duty of care to Ryan?

A: Ryan’s contact with the operation was assessed and agreed by people with more rank than me.

Q: You were just following orders?

A: I’m not answering that.

Q: I’ll rephrase. Beyond the referrals you made to your superiors, did you ever feel that you, personally, had a duty of care to Ryan Kennedy?

A: Of course I did.

Q: What adjustments did you make?

A: I did my best. I didn’t encourage him to commit offences. But Ryan was not a key member of the Bluds and he wasn’t central to the operation.

Q: But still, he was considered close enough to Mr Oliver to be useful?

A: No one could have anticipated that he would be supplied with a firearm.

Q: Mr Oliver was dealing in firearms. That was indeed the focus of the police operation.

A: We knew Shakiel was intending to take delivery of firearms. We had no intelligence whatsoever that he was already in possession of a firearm.

Q: But you knew that he was a very dangerous man. It was a dangerous environment.

A: That was why he was the target of an operation. Because London, and indeed the United Kingdom, needs protection—

Q: If I can finish my question. Mr Oliver was a man who fully intended to use firearms—

A: No, we did not have intelligence that he intended to use firearms, just to acquire them. To deal in them in order to increase his power and his wealth. We had no intelligence that he had a firearm at the time. Nor could we have anticipated that he would give a firearm to a fifteen-year-old boy. On London’s streets firearms are expensive commodities, and difficult to obtain. Toplevel criminals don’t just give them away to teenage boys.

Q: Prior to Detective Inspector Shaw’s death, Shakiel’s right-hand man, Jarral, had been arrested. You didn’t anticipate either that that would have a destabilising effect on the handover of the illegal imported weapons.

A: That kind of assessment is above my pay grade. I’m just the officer on the ground, getting information. I’m the cannon fodder, you know, the one you throw under the bus—

Q: An hour or so before the shooting of Kieran Shaw what had happened?

A: Shakiel Oliver had been arrested accepting delivery of automatic weapons.

Q: And you?

A: I was with Shakiel at the time of his arrest.

Q: What do you know of Ryan’s involvement in that?

A: CCTV showed that Ryan was acting as lookout. He cycled past the vehicle that I was in with other police officers after the arrest. I knew nothing of this at the time.

Q: Ryan said he saw you shake one of the officers’ hands.

A: I can’t give evidence as to what Ryan saw.

Q: But you can tell the court whether you shook one of the officers’ hands?

A: I shook one of the officers’ hands. It had been a long operation. We had seized an armoury. I was relieved it was over.

Q: You were someone Ryan confided in. He saw you at the scene of the weapons handover, and he may have seen you shaking the hand of a police officer. Shakiel Oliver had been arrested in front of him. You didn’t anticipate any fallout?

A: What can I tell you? It’s dangerous and risky dealing with dangerous and risky criminals.

Q: And after the arrest of Mr Shakiel Oliver you did what?

A: I went back to the flat.

Q: With the intention?

A: To arrest Ryan.

Q: How had you risk-assessed that decision?

A: Do you think that if I’d had any idea he might have a firearm, I would have put my own life in danger? In any case, I was not intending to let him into the flat at that time. If he’d appeared at the door, as I’d expected, I’d have called for assistance to have him arrested. I encountered him on the street.

Q: How had you managed the possibility of meeting him on the street?

A: It was bad luck. Two minutes either way and—

Q: Bad luck?

A: In the real world you can’t plan for everything.

Q: So, you were unlucky. You did meet him on the street, where he knew you resided and where you had often met him. He had come looking for you after he had seen that you were not what you had seemed to be. He forced you into the flat. This fifteen-year-old boy had seen you as someone he could turn to. A father figure, even.

A: Father figure? Come on.

Q: A friend, then?

A: His fence. A man he sold stolen goods to.

Q: You were a highly trained undercover officer. It was a part of your job to assess the states of mind of your targets. What do you think Mr Kennedy’s state of mind was when he entered your flat? What is your professional judgement as to his ability at that time to form clear intentions?

A: As to his intentions, Mr Kennedy said – and it will be on the recordings – he said, If I shoot you, it won’t be by accident. Then he shot my friend.

Steve Bradshaw slips out of the court and back onto London’s busy streets. He blends in: he’s good at that. He needs to walk quickly, but it’s almost impossible: there are too many people. Time and again he has to step off the pavement onto the road.

He tries to shake off the feeling that it has gone badly. Whatever he said in court they would find a way to misunderstand him.

Spy cop is one of the ridiculous catchphrases the journos are using about him. Silly, silly, silly, telly talk. Not one bit like the reality: living in a shit flat for most of two years, putting his own life both on hold and in danger, constantly having to make important decisions quickly. The lawyers only ask the questions they want answered. One of the things they don’t ask is how it feels to see a friend shot.

He realises that he has stopped walking. London continues around him. What will he do now? One option is to slip into the underground, crash in front of the TV with a beer. He decides instead to walk briskly home. It will take two hours. It will physically tire him. He needs that. Tomorrow he’s seeing Lizzie. He’s taking Kieran’s son to the zoo.

4

Lizzie wears an apron over her blue suit and silk shirt. She wipes the work surfaces in the kitchen.

‘How did you feel about your evidence?’ she says.

Steve shrugs. ‘No worse than expected. It was always going to be our fault that a criminal killed one of us.’

Lizzie shakes her head, although what the meaning of that is is unclear. Steve wonders about Lizzie, but he cannot bring himself to ask. Does she blame him? He can’t get out from underneath that question. And then he’s angry because why did Kieran have to come to the flat? Acting the hero. What a fool. Steve would have handled it much better on his own. And in his darkest moments he thinks he would have coped better too with being dead than with being the one in the room when Kieran was shot.

Lizzie holds out a Spiderman duffel bag. ‘Well, V23, everything Connor needs is in there. I’ve made you both sandwiches.’

‘You didn’t have to. I was going to treat us.’

‘Just taking him to the zoo will be treat enough.’

Connor has his feet on the seats of the tube train and Steve taps his shoes. ‘Come on, little man.’

Connor shuffles forward and stretches out his little legs. His feet dangle into space.

Steve says, ‘What’s your favourite animal, then?’

‘Elephants.’

‘Course it is. Stupid of me.’

Steve remembers those little wooden elephants in the hospital. Lizzie told him Kieran bought them in a stall in Hackney. They’d come all the way from Africa.

‘We can see them first if you like.’

‘No elephants at the zoo,’ Connor says.

‘Are you sure? They always used to have elephants.’

‘One of them had a sore foot.’

‘What?’

Connor speaks emphatically, as if Uncle Steve is being a bit slow. ‘One of them had a sore foot.’

Steve narrows his eyes. Oh yes, now he remembers. One of the elephants killed a keeper. That must be what Connor is talking about. In spite of himself, he smiles. Sore foot: it’s the perfect defence. Temporary loss of control: manslaughter. Couple of years. He sighs. Unless the jury particularly likes elephants. In which case it will be not guilty.

‘There’s elephants at Whipsnade,’ Connor says.

‘We could have gone to Whipsnade.’

‘There’s giraffes and zebras at the zoo.’

Steve says, ‘OK, so we’ll see them then. I like giraffes and zebras. Spots and stripes, they’ve got it covered. What’s not to like?’

‘And the turtles.’

‘Yes, and the turtles. Nice shells.’

‘And the otters.’

‘Yes, the otters too. Sweet little ears.’

‘And the lemurs.’

Steve laughs. ‘We’ll see all the animals, Connor. Any animals you want to see, we’ll see.’

The tube pulls into the station. An old lady with a stick and a red felt hat gets on. In a second Connor’s jumped onto the floor. He looks a bit wobbly on his little legs and Steve wonders whether he’s old enough to stand on the moving train. But Connor’s grabbed the rail and Steve decides to let him be. The lady sits and turns to Steve.

‘What a well-behaved little boy.’

‘I blame his mum.’

Connor is swinging on the standing rail and Steve smiles because Connor’s just like his dad: cocky.

‘Your daddy must be very proud of you,’ the lady says and turns back to Steve with an indulgent smile and a nod of appreciation.

‘Uncle Steve’s not my dad,’ Connor says.

The woman looks between them. Her face has clouded. It isn’t the pretty scene she had imagined after all. Steve can read her mind. She’s jumped to divorce and he’s the boyfriend.

Connor swings out like he’s a compass drawing a circle and Steve stops himself saying, Careful. Kieran wouldn’t have mollycoddled his son.

Connor says, ‘My daddy’s dead.’

‘Oh.’ The lady’s eyes widen. ‘I’m very sorry to hear that.’

Connor carries on swinging. ‘My daddy was a hero.’

The lady smiles kindly. ‘He was a hero, was he? Good for him.’

‘A bad man shot him.’

The woman recoils at this. Her hand goes to her mouth. There’s a moment before she speaks. ‘Your daddy, he wasn’t Kieran Shaw, was he? The policeman?’

Connor is completely unperturbed. ‘Yes. Kee-Ran-Shaw. He was my dad.’

‘Then he was a hero.’ The lady fumbles desperately in her purse.

Steve puts his hand up. ‘No, no, no. Thank you. But, no.’

She has tears in her eyes. ‘But won’t you let me buy him a treat?’

Steve says, ‘We don’t need money.’ Realising that sounds brusque he adds, ‘But thank you for your kindness.’ He stands up. ‘Come on, Con, it’s our stop.’

‘No it isn’t. One more stop.’

‘We’re getting off here; the walk will do us good.’

But it is too far for Connor, and Steve carries him most of the way piggyback.

5

They don’t call Lizzie to give evidence. She saw Kieran dying, but that is irrelevant. She was out of the room when the shot was fired. Neither prosecution nor defence consider that her evidence contributes to their case.

The jury retire just before lunch. Lizzie waits with Elaine, her family liaison officer, in the room for family members. One of the DCs from the MIT team brings them takeaway coffees and sandwiches. They scroll through their phones. Steve texts to say there will be pizza when she gets home. Connor wants to watch Horton Hears a Who!.

Lizzie’s mum has Connor from Wednesday. By lunchtime it has become clear that it isn’t going to be a quick verdict. Elaine produces some playing cards. She teaches Lizzie cribbage. On Thursday, at lunchtime, they are called into court. But the jury hasn’t come to a finding.

Instead, a young woman in heavy make-up whose glittery nails Lizzie spotted a few days into the three-week trial passes a note to the clerk to give to the judge.

He unfolds it, reads it. He passes it to the defence and prosecution.

‘I don’t think this need bother us too much.’

The jury are dismissed but told not to go all the way back to the jury room. After a short discussion they file back in.

‘DNA and fingerprints don’t go to the issues in this case,’ the judge explains. ‘The defendant doesn’t deny that he was in the room or that he was holding the gun. The issues at this trial are not forensic . . .’

But the jury member who passed the note is having none of that. She purses her lips and shakes her head. Presiding might be the learned His Honour Judge Mark Knapman QC, but she knows better and she isn’t going to be hoodwinked; the forensic evidence is very material to the decision the jury has been struggling with for so long.

Lizzie is scalded by fury. The whole criminal justice system having to be so patient around such stupidity! This three-week trial, its learned QCs with their keen juniors, the laborious laying out of evidence, the meticulous reconstruction of events; all of this in the hands of someone who has watched too much CSI and is completely missing the point.

The judge smooths his hands out across the bench.

‘To help you focus your discussions, and with the agreement of my learned friends, I am going to deliver a reminder of the facts that you have to decide upon.

‘You do not have to decide whether Mr Kennedy fired the gun or that the bullet caused the death of Detective Inspector Kieran Shaw.

‘What you are called on to decide upon is the state of mind of Mr Kennedy when he released the bullet. You must decide what, if anything, Mr Kennedy intended, and what he knew.

‘You should consider the murder and manslaughter charges in order, and the first charge that you should consider is that of murder.

‘To be guilty of murder a person must intend serious harm or to kill. That is, that at the time he performs the act that leads to death, the defendant must mean for serious harm or death to occur. Without this intent a person may kill, but still not commit murder.

‘So, in respect of the murder charge, the questions before you are: are you sure that Mr Kennedy released the trigger on the gun intentionally, and if he did so, was this with the intent of causing serious harm or death?

‘Whether this intent was towards Detective Inspector Shaw or to the man he had seen in the street, Mr Jermaine King, who he believed had murdered his friend, Spencer Cardoso, is irrelevant. If you are sure that Mr Kennedy intended to cause death or serious harm to either man at the time of the shooting, then you must find him guilty of murder.

‘If you cannot be sure that Mr Kennedy had formed this intent, then you must find him not guilty of murder and move on to considering whether he is guilty of manslaughter by unlawful act.

‘Manslaughter is sometimes called a “lesser charge” than murder. That is because the person committing manslaughter does not need to intend to cause serious harm or death to be guilty. The prosecution say that Mr Kennedy knowingly and unlawfully possessed a firearm. If that is the case, there is no defence to the charge of manslaughter.

‘However, the defence say that Mr Kennedy did not know that the weapon in his possession was a real firearm and not an imitation . . .’

Lizzie closes her eyes. The judge’s words swim over her into meaningless sound. She no longer wants to try to make sense of them. This fine slicing of time and intention, as if by a mandoline, seems to have no bearing on what had happened in that flat. Hearing the gunshot in the street and running up that narrow flight of stairs. Kieran on his back in the small room, surrounded by medics and police. His chest soaked in blood. Blood splashed on the broken window.

That boy, Ryan, who sits now so still and so carefully suited in the high dock, standing then in handcuffs by the flat’s boarded-over fireplace, blood on his chest and face.

Suddenly privileged in the police family that created itself in an instant around the wounded officer, she moved towards Kieran. His face was white and sticky, his lips pale. This man, in such pain and extremis, was already not the man she had known.

She said, ‘Love you,’ and he moved his head and looked at her and mustered something that may or may not have been a smile.

‘Don’t be ridiculous.’

That was the last thing he said to her. Don’t be ridiculous. Even with her eyes closed here in this courtroom, she presses her hand to her forehead. Don’t be ridiculous. For goodness’ sake!

No point in trying to make sense of it, the counsellor told her. Kieran’s brain was already dying when he said those words, all possible meanings slipping away from it. Still how many times has she gone over those three words and tried to find the salt of them sweetened by humour, by love too, if only by love.

She said, ‘You’re going to be all right,’ and he nodded and turned his face away, too busy with dying to stay with her. She stood back to let the medics work. How she regretted that now. Each second, so precious, and she had given away whole minutes. They lifted him onto the trolley bed and he was carried away from her down those narrow stairs.

The judge finishes talking. Lizzie opens her eyes and takes in the burnished solemnity of the court. The wooden panelling, the precise words, the meticulous arguments and counter-arguments: all this ceremonial makes not a dint on what happened in that flat. She glances at Ryan, who sits almost motionless, mostly staring straight ahead of him.

Connor had been too young to retain any memories of his father.

The jury are getting up, beginning to file out, and her eyes travel over the people who are struggling to make up their minds about something that seems so obvious. A tall guy in a blue drill workwear jacket who has been making notes throughout. Taking his responsibilities seriously. Taking himself seriously, too. A dumpy woman, who wears every day a different patterned dress, all in polyester. How many can she have? A grey-haired man in suit and dark tie. They are a lucky-dip assortment of London to have to rule on these arcane shades of meaning.

She thinks of them going home at the end of each court day. Catching the tube and sitting there, anonymous, with their store of new knowledge. Are they wise enough to know that this violence is something they do not comprehend? To be humble before the fact of it? Kieran lying there with his life leaving him. The CSI know-it-all with the manicured nails glances towards her. Lizzie should look vulnerable, try to arouse her sympathy; there is a lot more going on in this courtroom than the arguments of the lawyers. She turns back to Ryan. He is looking at her too but when she meets his eyes, he looks away.

He was there. He pulled the trigger. He must know he is guilty.

The jury has left and the prosecution barrister, Margaret Williams QC, is putting in a request to the judge – bearing in mind, My Lord, the circumstances of the deceased’s families. The childcare issues. The defence does not object. The judge is sympathetic: the interested parties can go home. Provided they can return within an hour, the court will wait for them to hear the verdict when the jury is ready.

The judge rises. The remaining entourage, pressed up against each other, are forced to dawdle their way out through the narrow doors. The defence barrister is deferential and sympathetic: doing his job but still enough room in his heart for sympathy. As they move down the stone steps the prosecutor – very grand in her gold-heeled court shoes and bright lipstick – smiles at Lizzie. ‘Won’t be long now, either way.’

She has the look of someone who doesn’t want to be detained but Lizzie puts a hand on her arm and pauses her on the stone steps.

‘It’s been a few days. Do you think they’re going to be hung?’

The prosecutor draws Lizzie aside and speaks quietly.

‘They won’t be hung. Not on every count, anyway. Maybe on the big one, but on the manslaughter charge the judge seems to have given fairly unambiguous directions that he’s guilty. He clearly knowingly possessed the firearm.’ She smiles and rows back on her certainty, just in case. ‘But you never can tell.’

‘And if they are hung on the murder charge, then what? A retrial?’

The QC winks conspiratorially. ‘We’re not there yet. Let’s wait for the jury.’

Margaret Williams QC is already walking briskly away, her wig in her right hand. She doesn’t want too much contact with the families. Just that exuberant introduction on the first day, like a galleon under full sail, and then every day afterwards a bright don’t-bother-me-I’m-busy smile. Probably nervous herself. A big job, and a difficult one. High profile. She’ll be wanting the guilty finding.