1,90 €

Mehr erfahren.

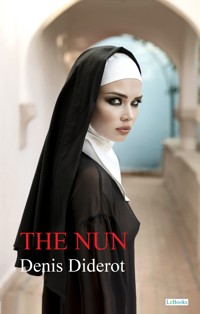

- Herausgeber: Lebooks Editora

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Serie: Clássicos Eróticos

- Sprache: Englisch

Denis Diderot (1713 — 1784) was a French philosopher and writer. Notable during the Enlightenment, he is known for being the co-founder, editor-in-chief, and contributor to the Encyclopédie, along with Jean le Rond d'Alembert. However, one of his most remarkable and provocative works was The Nun. In 1760, Denis Diderot and his friends wrote a series of letters to the Marquis de Croismare. The letters pretended to be from Suzanne Simonin, an illegitimate daughter forced to take religious vows to atone for her mother's guilt. Having escaped the convent, she apparently sought the marquis's help in annulling the vows. In her letters, the nun narrates the details of her forced confinement, describing its effect on her understanding of religion and faith. The novel's reputation as a succès de scandale is largely due to the frank and explicit depiction of the prevalent cruelty in monastic institutions and the narrator's discovery of both eroticism and spirituality. The work once again stirred public opinion when, in 1966, Jacques Rivette's film adaptation was banned for two years. The Nun, deservedly, is part of the famous collection: 1001 Books to Read Before You Die.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 320

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

Denis Diderot

THE NUN

Original Title:

“La Religieuse”

Contents

INTRODUCTION

THE NUN

INTRODUCTION

Denis Diderot

1713-1784

Denis Diderot was a prominent French philosopher, art critic, and writer during the Enlightenment. Born in Langres, France, Diderot was initially educated by Jesuits and later moved to Paris to pursue a career in literature and philosophy. He is best known for his role as co-founder and chief editor of the Encyclopedia, a monumental work that aimed to gather and disseminate the knowledge of the time.

Throughout his life, Diderot faced financial difficulties and often struggled to support himself through his writing. However, he remained committed to his intellectual pursuits and became a central figure in the Enlightenment movement. Diderot's contributions to philosophy, literature, and art criticism were vast and varied, encompassing works that challenged established norms and promoted reason, science, and humanism.

One of Diderot's notable works is The Nun (La Religieuse), also known as Memoirs of a Nun. Written in 1760 and published posthumously in 1796, The Nun is a novel that critiques the abuses and injustices of the religious institutions of the time. The novel is presented as a series of memoirs written by a young woman named Suzanne Simonin, who is forced into a convent against her will.

Suzanne's story begins with her being coerced into taking religious vows due to her family's desire to conceal her illegitimacy. Throughout the novel, she faces severe mistreatment, psychological torment, and oppression at the hands of the nuns and the abbess. Diderot uses Suzanne's harrowing experiences to expose the corruption and cruelty within the convents, questioning the morality and efficacy of forcing women into religious life.

The Nun is a powerful critique of the restrictions imposed on women and the lack of personal freedom afforded to them in the name of religion. Diderot's portrayal of Suzanne's struggle for autonomy and justice resonated with readers and contributed to the broader Enlightenment discourse on individual rights and institutional reform.

Diderot's The Nun was not only a significant literary achievement but also an important social commentary that highlighted the need for change within religious and societal structures. The novel's themes of personal freedom, resistance to oppression, and the critique of institutional power remain relevant and influential to this day.

Denis Diderot passed away on July 31, 1784, in Paris, France. His legacy as a pioneering thinker, writer, and editor continues to be celebrated for his contributions to the Enlightenment and his enduring impact on literature and philosophy. The Nun stands as a testament to his courage in addressing controversial subjects and his commitment to advocating for reason, justice, and human dignity.

THE NUN

The answer of the Marquis de Croismare, if indeed he replies to me, will provide the first lines of this story. Even before I wrote to him, I wished to know him. He is a man of the world, grown illustrious in the service; he is elderly and has been married; he has a son and two daughters, whom he loves and by whom he is cherished. He is of good birth, enlightened, intellectual, gay, fond of the fine arts, particularly of anything original. Praises have been sung me of his warm heart, honor, and probity. And I judged by the lively interest he took in my affairs and by all that I have been told of him that I did not compromise myself by applying to him. But he can hardly be expected to change my lot, without knowing all about me; and it is for this reason that I am resolved on overcoming my vanity and repugnance, and that I undertake these Memoirs, in which I describe some part of my misfortunes without art or skill, but with the simplicity of youth and with my natural frankness. Then in case my protector wished me to finish them, or should I possibly desire to do so myself later, when I may perhaps have forgotten incidents which will have become remote, I have concluded with an outline, which ought to be enough to recall everything to my memory, since I shall always remain deeply affected by what I have gone through.

My father was a lawyer. He had married my mother rather late in life and had three daughters. There was more than enough money to settle them all comfortably; but to do that my parents would have had to love all their daughters equally. And I am far from able to accord them such praise. Certainly I was worth more than the others as regards the attractions of mind and appearance, character and talents. And this was apparently a source of affliction to my parents. The advantage nature and study had given me over my sisters became a positive inconvenience to me; and so I desired from my earliest years to resemble them, that I might be loved, cherished, made much of, and excused as they were. If it happened that someone said to my mother: “You have charming children” it was never made to apply to me. I was sometimes handsomely avenged for this injustice, but the praises which I had received cost me so dear when I was alone that I would as lief have been treated with indifference or even insult. For the more predilection Grangers showed me the greater was the bad temper exhibited once their backs were turned. How often have I wept at not having been born ugly, silly, stupid, and proud: in a word, with all those faults which my parents found so admirable in my sisters. I asked myself whence came this strangeness of temper in a father and mother otherwise respectable, just and pious. Shall I admit it, my lord? some observations that escaped my father in his wrath (for he was a violent-tempered man), some incidents collected at different times, the remarks of neighbors, hints of servants, all made me suspect a reason which would in some measure excuse them. Perhaps my father was none too certain about my birth; maybe I recalled to my mother a fault she had committed, or the ingratitude of a man to whom she had too gladly listened. How can I tell ? But even if my suspicions were ill-founded, there is no risk in confiding them to you. You will burn this writing and I promise to burn your answers.

As we came into the world in quick succession, we grew up together. Eligible offers were made. A charming young man paid his addresses to my eldest sister but I quickly perceived that it was for me that he really cared, and that she would never be more than the excuse for his presence. I foresaw all the trouble which his preference might bring on me, and I warned my mother. Perhaps this was the only thing I ever did which pleased her, and you will see how I was rewarded. Four days, or at least a few days, later I was told that a place in a convent had been decided upon for me, and the very next day I was taken there. I was so unhappy at home that this did not distress me, and I went off very lightheartedly to my first convent, saint Mary’s. Meanwhile my sister’s lover, as he no longer saw me, forgot all about me and married her. He is a solicitor at Corbeil named M.K., and they are as wretched together as possible. My second sister was married to a M. Bauchon, a silk-merchant in Paris, rue Quincampoix, and they are quite reasonably happy.

My two sisters being set up in life, I assumed that my parents would now think of me, and that before long I should leave the convent. I was then sixteen and a half. Fine dowries had been found for my sisters and I promised myself a lot equal to theirs. My head was full of attractive schemes, when I was summoned into the parlor. There I found Father seraphim, who had been my mother’s spiritual director as well as my own. Hence, he experienced no embarrassment in explaining the motive of his visit. In fact, I was to take the veil. I protected against this strange proposition, and declared roundly that I felt in no way drawn towards the cloister.

“ So much the worse for you,” he answered, “for your parents have denuded themselves for your sisters and I cannot at all see what they could do for you in the straitened circumstances to which they are reduced. Think it over. You must either enter this House permanently or go away into some provincial convent at which you will be received for a modest yearly payment, and which you will be able to leave only on the death of your parents; and that may still be a long way off! ”

I complained bitterly, and shed a flood of tears. The superior, who had been informed about everything, was waiting for me as I left the parlor. I was in a state of indescribable distress. She said: “ What is the matter, my dear child? ” (she understood better even than I did); “ what a state you are in! I have never seen anything like it. You quite terrify me. Have you loft your father or mother? ” I thought of throwing myself into her arms and answering: “ Would to God I had 1 ” But I contented myself with crying out: “ Alas ! I am a wretched girl, whom everyone hates and wants to bury alive here.” she allowed the torrent to pass and awaited the moment of calm. I explained to her more clearly the announcement that had just been made. She seemed sorry for me, and encouraged me not to embrace a state for which I felt no vocation. She promised to pray, remonstrate, and plead on my behalf. Oh, my lord, how insincere these Mothers superior are! You can have no idea of it. She wrote indeed, but knew perfectly well beforehand the answers she would get. She communicated them to me and only long afterwards did I learn to doubt her good faith. Meanwhile the time allowed me to make up my mind was over, and she came to tell me so with studied grief. First, she remained silent and then threw me out a few words of commiseration, from which I gathered all the rest. There followed a scene of despair, and indeed I shall have scarcely any other kind of scene to describe to you. Mothers superior are postmistresses in the art of self-control. But at last she said, and I really believe she was crying: “ So, child, you are going to leave us and we shall not see you again ” and some other remarks which I did not hear. I had thrown myself onto a chair, and kept silent or broke into sobs, remained motionless, or got up, went sometimes to lean against the wall and sometimes to give way to my grief upon her breast. But after this she added: “ There is one thing you might do. Listen to me, and never mention a word of the advice I am going to give you. I count on your absolute discretion, and for nothing in the world would I lay myself open to reproach. What are you being asked to do? To become a novice. But why not do so? You are committed to nothing except to live with us for two years. One can never tell who will be living and who will die. Two years is a long time. A lot can happen in two years.” And she joined many caresses, protestations of friendship, and much false sweetness to her insidious proposals.

“ I knew where I was; I knew not whither I was being led ”, and I let myself be persuaded. Then she wrote to my father. Her letter was excellent: indeed it could not have been bettered. My sufferings, my grief, my protects were in no wise passed over, and I assure you that a girl more clear-sighted than myself would have been deceived. And so it ended with my giving my consent. How quickly everything was got ready! The day was fixed, my clothes made, the moment of the ceremony come, without there seeming to-day to have been any interval between these steps.

I forgot to tell you that I saw my father and mother, that I left no stone unturned to soften them, and that I found them inflexible. The Abbé Blin, Doctor of the sorbonne, gave me the exhortation. The Bishop of Aleppo passed me the habit. The ceremony is not gay in itself, and on this occasion it was as gloomy as could be. Though the nuns pressed round me to support me, I felt my knees giving way a score of times, and I all but fell on to the steps of the altar. I saw and heard nothing and was quite brutish. They led me and I went. They questioned me and answered in my place. At last the cruel ceremony was over; everyone withdrew, and I remained with the flock to which I had just joined myself. My companions surrounded me and embraced me, saying: “Look, sister, how handsome she is! How well the black veil suits the whiteness of her complexion! How nicely it rounds off her head and fills out her cheeks ! How beautifully the habit shows off her figure and arms.” I scarcely heard them, I was so unhappy. But I must confess that once alone in my cell I remembered their flatteries and could not help looking in my small mirror to judge for myself, and it seemed to me that they were not entirely undeserved. There are special honors attached to such an occasion, and they were particularly grand in my case, but they made scarcely any impression on me. People pretended to think the opposite and told me so, though it was obvious nonsense. In the evening, after prayers, the superior came into my cell. “ Really,” she said after scrutinizing me a little, “ I cannot understand your objection to the habit. It suits you marvelously and you are quite charming. Sister Susan is a very good-looking nun. You will be all the more popular on that account. Come along, let’s see; walk a little. You don’t hold yourself sufficiently upright. You mustn’t stoop like that.”

She arranged my head, feet, hands, Waist, and arms for me — quite a lesson by Marcel{i} on monastic elegance. For each state of life has its own brand. Then she sat down and said: “ That’s right, but now we must talk seriously. Two years have been gained. Your parents may change their plan: you perhaps will want to remain when they want to take you away.”

“Never believe it, Madam.”

“You have been long among us, but you do not know our life. It has its pains no doubt, but also its consolations.”

You can very well imagine all that she added about the world and the cloister: it is written everywhere and always in the same way. For, heaven knows, I have had to read any amount of the rubbish that the monks have poured forth about their state, which they know well and hate, directed against the world, which they attack, love, and do not know.

I will not go into the details of my novitiate. Were all its rigors observed, no one would survive it. As a matter of fact, it is the pleasantest period of conventual life. A Novice Mistress is the most indulgent sister imaginable — her mission is to hide from you all the thorns of the profession. As a course of seduction, nothing could be more subtle or refined. She it is who deepens the darkness surrounding you, rocks your cradle, puts you to sleep, imposes on you, and fascinates you. My own was particularly attached to me. I do not believe that any young and inexperienced nature could resist such deadly art. The world has its precipices, but I do not believe that the slope leading down to them can be so gentle. If I sneezed twice, I was excused Divine service, work, and prayer. I went to bed earlier, got up later: the rule ceased for me. Believe me, my lord, there were days when I sighed for a moment of self-sacrifice. Nothing disagreeable happens in the outside world without your hearing of it. True stories are rearranged, false ones invented, while unending praises and thank-offerings are made to God, Who has screened us from such humiliating adventures. But the hour approached, which I had sometimes desired to hasten. Then I became moody, feeling my objections awaken and increase. I went and confided them to the superior or to our Novice Mistress. These women have their revenge on you for the way you bore them. For you must not suppose that they enjoy the hypocritical part they play and the ridiculous remarks they are compelled to repeat to you. Finally, all this becomes stale and repulsive to them: but they force their natures; and all for the few hundred pounds which come into the house. This is the important object for which they tell lies all their lives and prepare innocent girls for forty or fifty years of despair, and perhaps for eternal misery. For it is certain, my lord, that out of a hundred nuns who die before fifty there are exactly a hundred who are damned, not counting those who go mad, brutish or raving in the process.

One day one of these poor demented creatures escaped from the cell, where she was kept shut up.

I saw her. It depends, my lord, on the way you treat me whether I am to date my good fortune or my ruin from that moment. I have never seen anything so horrible. Her hair was in disorder and she was almost naked; she dragged after her iron chains; her eyes were wild; she tore out her hair; she struck her breast with her fists; she ran about howling; she called down hideous imprecations on herself and others; she looked for a window to hurl herself out of. Terror seized me; I trembled in every limb; I saw my fate in that of the unhappy woman, and immediately I decided in my heart I would die a thousand times over before exposing myself likewise. They foresaw the effect which this sight might have on my mind and thought they must counteract it. I was told any number of ridiculous and self-contradictory lies about this nun; how she was already deranged when she was received; how she had had a great fright at a critical time; how she had become subject to visions; how she thought herself in communication with angels; how she had read some pernicious books, which had affected her mind; how she had listened to some extravagant moral reformer, who had so terrified her with God’s judgment that her mind had been shaken and then completely unbalanced; how she never saw anything except demons, hell, and a gulf of fire; adding that they were very unhappy about it; that they had never had anything like it before in the house; and anything else you please. But this made no effect on me. Every moment my mad nun came back to mind and I renewed my oath to take no vow.

The moment had, however, come when I must prove that I could keep my word. One morning, after service, I saw the superior come into my cell. She had a letter in her hand and her expression was one of sadness and discouragement: her arms were hanging down listlessly, and her hand seemed hardly strong enough to hold the letter; she looked at me and tears seemed to be standing in her eyes. She was silent and so was I. She waited for me to speak First, but I restrained myself. She asked me how I felt, said that the service had been long that day, that I had coughed a little and that she thought I was unwell, to all of which I answered: “No, Mother.” she still held the letter hanging from her hand, and in the midst of her questions she put it on my knees, so that her hand still partly held it. Finally, after putting me some questions about my father and mother and having observed that I did not ask what this paper might be, she said: “ Here is a letter.” I felt my heartbeat at the word, and I added in a broken voice, with trembling lips: “ From my mother?”

“ That is so. Come, read it.”

I collected myself a little, took the letter and read it, at first fairly coolly; but as I continued, terror, indignation, anger, fury, different passions succeeded each other in my heart. My tone of voice, my expression changed from moment to moment. Sometimes I hardly held the paper or held it as though about to tear it up; or I clutched it violently as if tempted to crumple it and throw it right away from me.

“ Well, my child, and what is your answer? ”

“ You know quite well.”

“ No I do not. Times are bad, your family has had losses. Your sisters’ affairs are in disorder: both have a large family. Your parents impoverished themselves at the moment of the marriages and have since ruined themselves to support their children. They cannot possibly do anything satisfactory for you. You have taken the habit: the necessary expenses were paid. You held out hopes for the future when you took this step. The rumor of your coming profession has spread abroad. For the rest, count on my help. I have never driven anyone into Religion; it is a state to which God calls us, and it is very dangerous to mingle His voice with one’s own. I shall not attempt to speak to your heart if Grace does nothing. Till now, I have not to reproach myself with another’s unhappiness. Am I likely to begin, my child, with you who are so dear to me ? I have not forgotten how it was at my persuasion that you took the first step, and I will not let people abuse this fact to engage you further than you will. Come, let us concert a plan. Do you wish to make profession ? ”

“ No.”

“ You feel in no way drawn to the religious state?”

“ No.”

“ What do you want to be then ? ”

“ Anything except a nun. I do not want to be one, and I will not be one.”

“ Very well. You shall not be one. We will draw up an answer to your mother.”

We agreed on the general lines. She wrote a letter which she showed me and which I thought excellent. Meanwhile the Director of the House was dispatched to me and also the doctor, who had preached the sermon on my taking the habit. I was recommended to the Novice Mistress and saw the Bishop of Aleppo. I crossed swords with some pious women who meddled in my affairs, though they did not know me. There were continual conferences with monks and priests. My father came; my sisters wrote; my mother appeared last. I resisted everything. Meanwhile the day was chosen for my profession. Nothing was neglected to obtain my assent; but when they saw it was useless to ask for it they decided to get along without it.

From that moment I was confined to my cell; silence was imposed on me; I was separated from everybody and thrown on my own resources. I saw quite plainly that they were resolved to dispose of me without my consent. I was determined not to make any profession. That was definite, and none of the terrors, true or false, with which I was threatened shook my resolution. Still, I was in a deplorable state. I did not know how long it might last — and suppose it stopped, I knew still less what might happen to me. Amid these uncertainties I took a step, my lord, which you will judge as you may. I no longer saw anybody, not the superior, or the Novice Mistress or my companions. I had the first of these summoned and pretended to fall in with my parents’ wishes. But my plan was to end this persecution with a scandal, and publicly to protest against the meditated violence. I told them that they were masters of my fate and could dispose of me as they would; they demanded I should make my profession and I would do so. In a moment joy spread through the House and all was caresses once more, with the old flattery and cajolery. God had spoken to my heart. No one more than myself was made for the state of perfection. It was impossible it should not be so, and it had always been expected. No one who is not really called ever performed their duties with the edification and consistency I had shown. The Novice Mistress had never seen a more evident vocation in any of her pupils. She was surprised at the difficulties I had made, but she had always said to the Mother superior that they must hold fast and that it would pass; that the best nuns often went through these crises; that they were suggestions of the Evil One, who redoubled his efforts when about to lose his prey; that I was now about to escape from him and henceforth it would be roses all the way: that the obligations of the religious life would be all the easier for my having so much exaggerated them, and that the sudden weighting of the yoke was intended by Heaven to make it seem less heavy afterwards. I thought it curious that the same thing came from God or the Devil, just as one chose to look at it. Religion can provide many cases of the same kind. Some of my consolers said that my thoughts were so many instigations of Satan and others that they were so many inspirations from God. One and the same ill comes either from God who proves or from the Devil who tempts us.

I conducted myself discreetly, and thought I could answer for myself. I saw my father — he spoke to me coldly; my mother, and she kissed me. I received letters of congratulation from my sisters and many others. I knew that a M. Sornin, Vicar of saint-Roch, would preach the sermon and that M. Thierry, Chancellor of the University, would receive my vows. Everything went well till the evening of the great day, except that having learned that the ceremony was to be secret and that there would be very few present and that the church door would be open only to relations, I invited, by means of the doorkeeper, all my friends of both sexes who lived near. I had permission to write to some acquaintances. All this unexpected concourse presented itself at the door. They could not be excluded, and the congregation was just about what was needed for my plan. How terrible, my lord, was that last night! I did not get into bed, but sat on it and called God to my assistance. I raised my hands to the heavens and called on them as witnesses to the violence done me. I visualized my part at the foot of the altar, a young girl protesting loudly against an action to which she had apparently consented, the shocked feelings of the company, the despair of the nuns, the rage of my parents.

“ O Lord ! What is to happen to me? ”

As I pronounced these words a general weakness overcame me and I fell fainting on my bolster. A shivering fit succeeded the fainting, when my knees beat together and my teeth chattered noisily. This shivering fit was followed by a terrible heat and my mind grew clouded. I do not remember having undressed or having left my cell. But I was found naked but for my shift, Wretched on the ground at the door of the superior, motionless and almost lifeless. All this I learned subsequently. Next morning I found myself in my cell, my bed surrounded by the superior, the Novice Mistress, and those who are called assistants. I was much depressed. I was put some questions, and it was clear from my answers that I had no knowledge of what had occurred. Nobody spoke of it. I was asked about my health, if I persisted in my blessed resolution, and if I felt strong enough to support the fatigue of the day. I answered, “ Yes ”, and contrary to their expectation, they did not have to alter their plans.

Everything had been arranged the day before. The bells were rung to announce to everyone that a girl was to be made wretched. My heart still beat. They came to dress me; it was a day for dressing-up. When I now recall all those ceremonies, I feel that they contain much that is solemn and very touching to an innocent girl, not led elsewhere by her temperament{ii}. I was taken to Church; Holy Mass was celebrated. The good Vicar, who gave me credit for a resignation which I was far from feeling, and preached a long sermon, every word of which seemed nonsense to me. There was something preposterous in all his observations about my happiness, my grace, my courage, my zeal, my fervor, and the other fine sentiments which he attributed to me. I was disturbed by the contract between his praise and the step I was about to take. For a few moments I wavered, but it was not for long. I only felt the more strongly that I lacked all the qualities that go to making a good nun. The terrible moment at length arrived. As I entered the place where I had to make my vows my legs gave way beneath me. Two of my companions held me under the arms. My head sank on to one of them as I dragged myself along. I know not what passed through the minds of those present, but in fact they were watching a young victim being dragged dying to the altar; and there arose everywhere sighs and sobs, among which, I am certain, those of my parents were not to be heard. Everyone was standing up; the young people had clambered on to chairs or were clinging to the bars of the grille, and there was a moment of deep silence as he who presided at my profession said to me: “ Mary Susan Simonin, do you promise to tell me the truth? ”

“ I do.”

“Is it of your full pleasure and free will that you are here? ”

I replied, “ No ”, but my companions answered for me, “ Yes.”

“ Mary Susan Simonin, do you promise to God chastity, poverty, and obedience? ”

I hesitated a moment; the priest waited; and I answered: “ No, sir.”

He began again.

“ Mary Susan Simonin, do you promise to God charity, poverty, and obedience ? ”

I answered in a firmer voice:

“ No, sir, no.”

He stopped and said: “ My child, collect yourself and listen.”

“ Monsignor,” I said, “ you ask me if I promise to God chastity, poverty, and obedience. I have heard you and I answer ‘ No ’.”

Then, turning towards those present, from whom a loud murmur was arising, I made a sign that I wished to speak. The murmur topped and I said: “ Sirs, you, and particularly father and mother, I call you all to witness . . .”

At these words one of the sisters let down the curtain of the grille, and I saw that it was useless to continue. The nuns surrounded me and overwhelmed me with reproaches. I lifted without saying a word. I was led into my cell and shut in under lock and key.

There, abandoned to my own reflections, I began to take courage again; I went over my actions in my mind and saw nothing to repent of. I perceived that, after the scandal I had caused, I could not possibly remain there long, and hoped they might not dare to send me to a convent again. I had no idea what would be done with me, but I could conceive nothing worse than becoming a nun despite oneself. For a long time I was left without any news. Those who used to bring me my food came in, put my dinner on the floor, and went away without a word. After a month had passed, I was brought ordinary clothes and gave up those of the House. The superior came in and told me to follow her. I followed her to the door of the convent. There I got into a carriage in which I found my mother quite alone. I sat down with my back to the horses and the carriage Parted. We remained opposite each other for some time in complete silence. I lowered my eyes and had not the courage to look at her. I do not know what came over me, but suddenly I threw myself at her feet and bent my head upon her knees. I did not speak, only sobbed and choked. She rebuffed me unfeelingly. I did not get up: blood came to my nose; I seized one of her hands despite her efforts. Then, watering her hand with my tears and the blood which was flowing from my nose, and pressing my mouth against this hand, I kissed it and said to her: “ You are still my mother: I am &ill your child.” she answered (repelling me still more roughly and snatching her hand from mine): “ Get up, wretched girl, get up.” she put so much authority and strength into her voice that I felt I must escape her gaze.

My tears and the blood, breaming from my nose, ran along my arms, and I was quite wet before I noticed it. From something she said I judged that her dress had been soiled and that this displeased her. We arrived home, where I was immediately conduced to a little room that had been prepared for me. On the staircase I once more threw myself at her feet and held her back by her dress. Despite all this she would do no more for me than turn and dart at me an angry look with head, mouth, and eyes, which you may imagine more easily than I can describe.

I entered my new prison, where I remained six months. My food was brought to me, and I had a servant to look after me. I read, worked, wept, and sometimes sang — and so the days passed by. A secret feeling gave me strength — that I was free and that my lot, however hard, might change. But it was decided I should be a nun, and a nun I became.

So much inhumanity and obstinacy on the part of my parents finally confirmed me in my suspicions about my birth. I have never been able to find any other excuse for the way in which I was treated. My mother apparently feared that I should revert to the subject of the division of the property, ask for my part of it, and thus make a natural child share on equal terms with the legitimate offspring. But what had been only a conjecture was soon to become a certainty.

While I was locked up at home, I practiced but little the external forms of worship, though I was sent to confess on the eve of the great feasts. I told you I had the same Director as my mother. I talked to him and recounted all the hard treatment to which I had been subjected for three years. He knew it already. Of my mother particularly I spoke with bitterness and resentment. This priest had embraced his calling late in life, and was a humane man. He listened to me quietly and said: “ Pity your mother, my child, pity her rather than blame her. Her soul is good, and it is despite herself that she uses you thus.”

“ Despite herself! And what constrains her, pray ?

Did she not bring me into the world ? What difference is there between my sisters and me? ”

“ A great deal I ”

“ A great deal ? I cannot understand your answer at all. . .

I was about to enter on a comparison between my sisters and myself when he stopped me, saying: “ Come, come, inhumanity is not your parents’ failing. Try to be patient with your fate and at least make a virtue of that before God. I will see your mother, and you may be sure that I will use all my influence over her to help you.”

That “ a great deal ” with which he had answered me was a ray of light. I no longer doubted the truth of what I had surmised about my birth.

The following Saturday between five and half-past, as the day was closing in, the servant who waited on me came upstairs to me and said: “ Your mother says you are to dress.” And an hour later: “ Your mother wishes you to come downstairs with me.” I found a carriage at the door, into which the servant and I stepped, and I learned that we were going to the Cistercians to see Father seraphim. He was waiting for us alone. The servant withdrew while I went into the parlor. I sat down, feeling upset and inquisitive about what he had to say to me. This is what he said:

“ I am going to explain the secret of your parents’ severity towards you, and have obtained your mother’s permission to do so. You are sensible, intelligent, and strong-minded, and have also reached an age when you could be entrusted with a secret even if it did not concern you. A long time ago I exhorted your mother to reveal to you what you are only now to learn. She could never bring herself to do it. It is hard for a mother to confess a grave fault to her child. You know her character. It is not of the kind which makes it easy to admit in this way a sort of humiliation. She hoped to be able to bring you round to her plans without sinking to this last resort. She was mistaken, and now regrets it. To-day she has come round to my opinion, and has charged me with the task of telling you that you are not the daughter of M. Simonin.”

I immediately replied: “ I suspected as much.”

“ Well then, consider seriously whether your mother can, without, or even with, the consent of your father, give you a position on an equality with those who are not your sillers, or whether she can admit to your father a fact about which he is already far too suspicious.”

“ But, sir, who is my father? ”

“ I am not in her confidence as to that. But it is only too certain that your sisters have been prodigiously favored and that every possible precaution has been taken by marriage contracts, conversion of real into personal property, stipulations, trusts, and other means to reduce your share to nothing, against the event of your being one day able to apply to the law for restitution. If you lose your parents, you will find there is little for yourself. You refuse the offer of a convent — perhaps one day you will be sorry you are not there.”

“ That is impossible; I ask for nothing.”

“ You do not know what pain, labor, and indigence mean.”

“ I know at least the price of liberty, and the burden of a state for which one has no vocation.”

“ I have said what I had to say, it is for you to think it over.”

He then got up.

“ One question more, sir.”

“ As many as you like.”

“ Do my sisters know what you have told me? ”

“ No.”

“ How could they then bring themselves to rob their sister, for such they think me? ”