Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

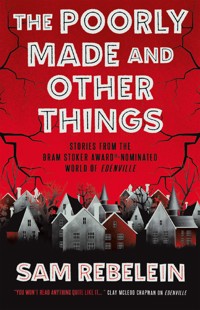

Return to the world of Renfield County from the Bram Stoker Award-nominated author of Edenville. Perfect for fans of Paul Tremblay and Eric LaRocca "You remember all the stories, right? Monsters and giants and kid-eaters and that guy in the tub? Of course you do…" There's something wrong in Renfield County. It's in the walls of the county's historic houses, in the water, in the soil. But far worse than that—it's embedded deep within everyone who lives here. From the detective desperate to avoid hurting his own family; to the man so consumed with feeling zen that he will pursue horrific, life-changing surgery to achieve it. From the townspeople taken by ancient, unknowable forces; to those who find themselves lost in the woods, pursued by the beasts who lurk within the trees. Yes, there's something very wrong in Renfield County—something that has been very wrong for a very long time. Something that is watching. Something that is hungry. From the mind of acclaimed author Sam Rebelein, return to the Bram Stoker Award-nominated world of Edenville in this interconnected series of short stories, and discover the true secrets of Renfield County.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 406

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

Map

The Stain: December 20, 1927

Hector Brim

My Name Is Ellie

Detour

Wag

Red X

10 PM on the Southbound G

So My Cousin Knew This Guy

Allison’s Face

And Every Thursday We Feed the Cats

Glitch

Re: The Stain: September 22, 2018

Acknowledgments

About the Author

PRAISE FOR THE WORLD OF EDENVILLE

“Edenville is pure cosmic gonzo... This jaw-dropping—apologies, jaw-ripping—novel earns its place amongst contemporary classics The Library at Mount Char and The Book of Accidents. You won’t read anything quite like it... not in our universe, anyway.”

CLAY MCLEOD CHAPMAN, author of Ghost Eaters

“There are many campus horror novels, but I think Edenville gets an A for AAAAAAIIIIIII! Sam Rebelein should be awarded a Master’s Degree in SCARY. A major new talent!”

R. L. STINE, author of Goosebumps and Fear Street

“In Edenville, there’s a captivating and equally irresistible kind of frenetic intensity pulsing from each and every page—the raw, powerful energy of a new, uninhibited talent in horror fiction. Sam Rebelein possesses the skillset of a venerated master and Edenville is a truly imaginative debut.”

ERIC LAROCCA, author of Things Have Gotten Worse Since We Last Spoke

“A mind-bending experience, Edenville is a transportive read that burrows down into the center of your mind and refuses to let go. There’s beauty and squick in these pages, and at its core, a whole lotta fun.”

KRISTI DEMEESTER, author of Such a Pretty Smile

“Nobody is writing the uncanny like Sam Rebelein. Edenville is an immersive, visceral, unsettling metafictional tale that lures you into the shadows, and then slowly expands your mind to the horrors that were always there. It’s Chuck Palahniuk mixed with Clive Barker and Stephen Graham Jones to create a funny, heartbreaking, original piece of fiction.”

RICHARD THOMAS, author of Spontaneous Human Combustion, a Bram Stoker Award® finalist

“Edenville is a tour de force of horror writing. The eerie atmosphere and building intensity will have you on the edge of your seat, while the sharply drawn characters and nightmarish imagery will keep you hooked from start to finish. Fans of Clive Barker and Stephen King at the peak of their powers won’t want to miss this one.”

TIM WAGGONER, author of A Hunter Called Night

“Edenville reinvents the small-town scary story as an onslaught of comedy, horror, and grotesquerie. Great, blood-curdling fun.”

STEPHANIE FELDMAN, author of Saturnalia

“Edenville is brilliant. Edenville is hilarious. Its denizens are as charming as they are hideous. This is a thrilling horror story with glorious characters occupying a deliciously rendered world.”

CHRIS PANATIER, author of The Redemption of Morgan Bright

“Edenville is a delightfully gooey blend of gothic, cosmic, folk and body horror churned by a sharp-bladed critique of academia.”

LUCY A. SNYDER, Bram Stoker Award®-winning author of Sister, Maiden, Monster

“The mundane horrors of rural and academic living collide with pure cosmic weirdness in Sam Rebelein’s Edenville. Not since Jason Pargin’s John Dies at the End have I been so horrified and grossed out by a book… I could say more, but honestly, the less you know about this book, the better. A fantastic debut.”

TODD KEISLING, Bram Stoker Award®-nominated author of Devil’s Creek and Cold, Black & Infinite

THE POORLY MADEAND OTHER THINGS

Also by Sam Rebeleinand Available from Titan Books

EDENVILLE

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

The Poorly Made and Other Things

Print edition ISBN: 9781803364704

E-book edition ISBN: 9781803364711

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: February 2025

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© Sam Rebelein 2025

Sam Rebelein asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

EU RP

eucomply OÜ Pärnu mnt 139b-14 11317

Tallinn, Estonia

+3375690241

For that timid young boy in Ohio who wantedto tell stories and all other kids like him

I had hung my shaving glass by the window, and was just beginning to shave. Suddenly I felt a hand on my shoulder, and heard the Count’s voice saying to me, “Good morning.” I started, for it amazed me that I had not seen him, since the reflection of the glass covered the whole room behind me. In starting I had cut myself slightly. . . . I saw that the cut had bled a little, and the blood was trickling over my chin. I laid down the razor, turning as I did so half round to look for some sticking plaster. When the Count saw my face, his eyes blazed with a sort of demoniac fury, and he suddenly made a grab at my throat. I drew away, and his hand touched the string of beads which held the crucifix. It made an instant change in him, for the fury passed so quickly that I could hardly believe that it was ever there.

“Take care,” he said, “take care how you cut yourself. It is more dangerous than you think in this country.”

—JONATHAN HARKER’S JOURNAL, Bram Stoker’s Dracula

7:18 p.m. (8 hours ago)

From: Rachel Durwood <[email protected]>

Subject: The Stain

Dear Tom,

So I’ve been a really bad sis. I meant to email you days ago but I just . . . kept not doing it. That’s lame of me, I know, but there it is. Sorry. Well, it’s Friday—no school tomorrow—so I figured I’d have a drink and finally finish writing this fuckin thing. Idk why I’ve been so weird about it. But I had a drink, then I had three drinks, and now I’m sitting on the floor of my bedroom with no lights on, hittin Send. Sorry haha.

I know I sank into my own shit after Mom, and I’m sorry about that, too. I know I’ve been bad about reaching out these last few years, ever since you moved. I know I was supposed to be there. We were supposed to be there for each other. But it’s been months since the funeral and not a word from me. What an asshole. Feel free to just write back, “Fuck you, Rachel.” I deserve it. I’ve abandoned you. I’m sorry. But I hope you still read this. It’s sort of an apology, but if I’m being honest, it’s really me trying not to be lonely, all cooped up in my sweaty-ass apartment, watching the sun set over the Bent. I just wanted to say hi.

But apologies in advance because this “hi” is going to be very long and very rambly. Like, “thirteen emails in a row” rambly. Being a high school sub, you don’t exactly communicate with a lot of adults, so it’ll feel good to just get this shit off my chest. Bear with me, okay?

So I’m writing you now because I’ve just finished kind of a weird project. That’s not an excuse or anything, but I’ve buried myself in this project the last couple weeks or so, and especially the last few nights. It’s really been . . . eating all my time. I’ve let it eat all my time. And I wanted to write to someone who might understand how I’ve been feeling. How I’ve been thinking about Mom and home and . . . Obviously, I’ve been thinking about you. So here I am, sharing this weird-ass project/apology with you, hoping that, even if you hate me for making you feel alone again, maybe you’ll still listen and understand.

I really hope you understand.

To start with, right after Mom died, I met someone online. He seemed nice. Some kind of doctor, from Lillian. Fancy, I know. I was scared and alone, and it was good to have someone to talk to. It’d been a while since I dated anyone, and . . . Idk.

Anyway, I went back to his place after our second date, and he had this big slab of Renfield wood hanging in his living room. Just . . . hanging there, over the mantel, with its weird stain. It made me feel cold all over. Like something was sliding over my bones, wrapping tight, squeezing the blood out of my limbs. This guy clearly thought it was cool, like he was showing off a Picasso or some shit. And when I asked him where he got it, he just gave me this horrible smile. So I was like, “You know what, I forgot my . . . thing in my car,” and I got the fuck out of there. Figured he’d try to drink my blood or something. You never know.

Or maybe he was fine, and I’m the freak. An oversensitive asshole who pushes people away. Maybe it’s both.

Maybe you just. Never. Know.

Either way, that night officially set me off on this project. And I’ve been obsessing over Renfield shit ever since. Not just the wood, but . . . everything.

You remember all the stories, right? Monsters and giants and kid-eaters and that guy in the tub? Of course you do. I say that like moving to the city made you forget about home. About good ole Renfield County. Well, maybe I’m nuts, but I think those stories answer . . . everything. I mean that, on top of all the other crazy-ass chaos here in Renfield County, I think Renfield provides a reason for Mom.

Did you need a reason for Mom? I did. I do. I really do.

So. I’ve been compiling all these anecdotes and articles and newspaper clippings into a kind of history report. I really have not slept the last few nights putting it all together, which I know is bad, I know you’re gonna give me shit about that, but it all makes sense, I swear, so please just keep reading? I know correlation doesn’t necessarily imply causation, and that’s fair. Whatever. But I’ve been trying to lay it all out and see where Mom fits. A lot of this you already know, of course, growing up here. But it’s been helping me to present it like this, all clear and linear. And I swear that, written out like this, it all makes sense. I swear it works through everything. I’m working through everything.

You’ll see.

Also, not gonna lie, it’s been kind of fun. I used to love history reports, in high school. So I’ve been digging through old police records, town archives . . . The ladies at the Edenville Library let you dig through a surprising amount of old shit if you’re a teacher. Even just an uncertified sub. They were thrilled I was even talking to them. So, yeah, that’s been a part of this, too. Just lonely ole me, in the library, with my old ladies, after dark. Havin a gas.

Fuck. That’s not fair of me to say. I ignored you and hung out with strangers instead. I suck. I’m sorry.

Look, I know I don’t deserve to ask you for anything right now, but please read all of this? It’s not bullshit. It’s about Mom. About us. So I need you to read this history report.

I need you to see:

Hundreds of years before the blood, the giant, Lawrence, and the damned, the Renfields were the first family to settle up here, far north in the New York woods. Because they were here first, the place was always known unofficially as Renfield County. Even when another family settled nearby, then a third, and then dozens. The land was always considered Renfield land.

Then came the morning of December 20, 1927, when the neighbors were the only ones left to clean up the blood. When there was so much of it, coating the stairs in a slick frozen sheet. It caked the floor of the kitchen, the foyer, the living room. A ragged red trail wound a route out the back door through the snow toward the barn—little Robert crawling away. Lawrence must have fired his shotgun from inside the house at Robert’s back, just as the kid was shoving open the door. The force of the shot sent Robert flying forward, and blew half the door off its frame. Later, that back door hung loose off its upper hinge, the lower hinge all dented debris. Wood flakes scattered around, buckshot in the wall. As the neighbors cleaned, the back door squeaked shut in the wind, clapped, squeaked open again. Outside, they could see the impression in the snow where Robert had dragged himself away from the house, wounds steaming in the winter air. He only made it two or three yards before Lawrence caught up to him.

Robert Renfield was four when his dad walked up behind him and blew his skull apart into the snow.

HECTOR BRIM

When she’d been gone for seven days, Gil took an ax to her piano. There’d been a small reception in his apartment after the funeral. Just Natalie’s parents, his mother, a handful of friends, and a few neighbors, including Mrs. Preston down the hall. Gil did nothing the entire time but wish them all gone. They had no comfort to give. No reassurances of higher meaning or better places, which they did not believe in. It wasn’t the kind of crowd they were, so it wasn’t the kind of crowd Gil needed. Mrs. Preston was maybe the only exception. She’d once spoken to him in the elevator, convincingly and unsolicited, about reincarnated pets and the spirit realm. But Gil squirmed in her company. Even her words of sympathy and reassurances felt small and cold. She seemed to sense this, leaving the reception early, patting his arm, and telling him, “Knock on my door if anything comes up.” There was something ominous about that. It made Gil squirm even more.

He finally managed to usher out everybody else, and as the door closed on Nat’s parents, he heard her mother say, “Don’t you think we should stay a bit longer?”

“No,” her father said, gentle. “Honey, come on. He wants to be left alone.”

The door shut on that. Alone vibrated throughout the apartment. For a long time, Gil didn’t move. Just stood there, still black-suited and formal, leaning against the door, needing to break something.

He turned. Gazed around at what had been their home. The tall ceilings, exposed brick. Paint they’d picked out together. Shelves filled with their books and photographs. And in the corner, those bone-and-black keys she’d hunched over with her long fingers, smiling as she played him the songs she wrote privately on lunch breaks.

“You could be a famous singer,” he’d told her once.

“But then I wouldn’t sing for you.”

The ax was buried in the hallway closet. Why he’d brought it with him when they’d moved down to the city, he couldn’t say. Maybe a part of him knew.

He loosened his tie. Rolled up his sleeves. Tore the closet door open. He knelt, began tossing old jackets over his shoulder. A tennis racket. Cobwebbed shoes. He dug the ax out of the dust. Hefted it back into the living room. And began hacking that piano to bits.

A long sliver of wood sliced at his cheek as pieces flew through the air. He felt the sting, but his entire stupid life stung now anyway, so what did it matter. He started with the keys, then moved sideways to the body. The jangling, springy chorus of snapping wires beat against his ears. He grinned, reveling in it. In the breakage of everything this once solid, formidable, smiling, perfect thing had been.

The ax crashed again and again.

A wire whipped across his bicep and he stopped. Stood panting above the wooden ruin, debris scattered across the floor. The ax hummed, frozen above his head. He felt himself pulse. Felt the leak down his arm, on his cheek.

The way the truck had hit her as she stepped unknowing off the curb, her arm had nearly cracked in half. Right along the bicep, right there. Feeling the wire now across that same spot, on his own arm, he was right back there, ax forgotten. Holding her as she went. Watching her arm twitch. Watching those long fingers go limp. The truck driver standing in the street, rocking back and forth on his heels. Retching. Weeping. Gil never heard his apologies. He just watched the arm twitch . . .

A sound. Soft, far-off. A kind of skittering slowly filled the apartment. Gil let the ax drop and clatter down out of his hand. He listened. Hundreds of insects, or tiny paws, scratching at the floor. Scrabbling across the wooden boards. A hollow, frantic scramble.

Gil frowned. Cocked his head. The noise grew louder. Louder. Began to roar throughout the room. But he couldn’t tell what it was.

Someone was standing behind him.

He turned. He was alone. Alone. Of course he was. She was gone. But for a second, he’d felt someone. Felt a pocket of displaced air or . . . something. He couldn’t explain it. He just felt watched.

The roar drowned this feeling out. His pulse, the leaks across his skin, quickened. He realized the noise was now joined by the coppery snaking whir of springs bouncing against each other. Gil turned again, looking around the room, starting to itch and sweat. What the hell was it? It sounded half-wooden, half . . . ivory. Sliding across the . . .

“Oh.”

He looked down.

The debris of the piano was moving.

As he watched, it rolled itself across the floor and, slow but steady, wove itself into a wide, crooked heart.

Gil blinked at it. Then threw up.

* * *

Because Gil belonged to a group of skeptical, scoffing Manhattanite friends, he didn’t really know what to do with . . . this. He didn’t have the tools or the language to process the supernatural. And he knew that was probably why his wife had waited an entire week to show herself like this. Nat knew—she must have known—that she’d have to wait for a break. A moment when he’d actually believe what he was seeing. Some kind of rock bottom. Well, watching him hack at her piano with an ax was probably the best chance she’d get. Like Gil, she’d been a skeptic, so he knew she’d think like that. She’d think, How can I really convince him? That is . . . if. If she really were . . . haunting him.

If.

Gil sat on the couch, knees tucked tight under his chin. He stared at the floor, at the wet spot from the puke he’d mopped up, right in the center of the piano heart. He’d carefully left the heart untouched.

He dug the heels of his hands into his eyes. Shook his head. Laughed. Tried to pull himself together. Laughed again. Gave up. He figured whatever was happening, he might as well go all in. And if he was starting to go crazy, then fuck it, what the hell.

He cleared his throat. Looked around the room, feeling self-conscious. “Alright,” he said. “Are . . .” He cleared his throat again. “Are you . . . here?”

There was a green and yellow light fixture in the hall. Something Natalie had brought down to the city, and loved.

It flickered on.

Gil began to cry.

A low rushing breathed down the hall. Gil held his breath. Sliding along the floor, around the corner, came a box of Kleenex. It slid to a halt just before the couch.

“Oh,” he said.

* * *

By sunset, he’d cried everything out. He sat calm on the couch, knees still tight against himself. Sore now, after sitting folded like that for hours. Clutching a wad of sodden tissues, he peered down the hall to the light fixture. Not sure what else to do, he said, just sort of confirming, “You’re really here.”

The light blinked.

Heat flooded his chest. “I . . . I miss you.”

The light flickered.

Gil sat up. He stretched his legs and his knees cracked. He wrung his hands, thinking.

“Are you . . . mad that I broke your piano?”

The light blinked twice.

Gil nodded. “Okay.” He sniffed, ran a hand under his nose. “Okay.”

He quickly figured out that he could ask Nat simple yes or no questions through the light. She’d blink once for yes, twice for no. As long as he kept the questions simple, she would answer.

Over the next three weeks, every chance he got, he’d speak with her. And, of course, told no one about it. Sometimes, she would float old pictures around to make him smile, or throw her jewelry across the room. Once, he’d felt a hand on his back. It made him jump and scream. But the hand wrapped around his shoulder, warm and safe. He melted into its company.

He sat under the hall light for hours every day. Talking, reminiscing, sometimes just staring. Silent. Trying not to ache.

Finally, he worked up the strength to ask the most terrifying question he could think of.

“Are you in pain?” Gil sat slumped against the wall. He stared up at the light. Waited for it to respond.

It didn’t.

“Hey. Are you in pain?”

The light flickered.

She wasn’t sure. She might be in pain. He could tell. Could feel it through the walls. Some kind of gnawing uncertainty. A looseness or unbalance. Something . . . off with her.

It was after another week of this—of talking and crying and clinging to her, of barely leaving his apartment just to be near her, even if it was just a flicker of who she was—that Gil finally decided she probably needed help.

Something echoed through his brain: Knock on my door if anything comes up . . .

Well. Something had definitely come up.

* * *

Even if she hadn’t offered, Gil probably would have trusted Mrs. Preston more than any of his skeptic pals. Especially now that he’d isolated himself for weeks, barely answering their texts and calls. He and Mrs. Preston weren’t friends. Not by any stretch of anything. They said hello to each other when they crossed paths in the lobby. In the elevator sometimes, they chatted politely about the weather, city life, reincarnated pets that one time, spirits rarely, and . . . well, they had chatted about Nat. Or with her, even, when she’d been there.

That hurt to think about.

Mrs. Preston was about eighty, a good fifty years older than Gil. He couldn’t say what she did for a living, really, or call her voice to mind unless he thought hard about it for several seconds. She was just some (and he felt bad thinking this) generic, squat, sweet old lady in his mind. And he was pretty sure then, he realized (and this made him feel slightly better), that to her, he was just some generic, tall, handsome young guy. But if anyone would believe in ghosts speaking through light bulbs and piano shards, he felt like it’d be her. Her door stank of sage and mystery every time he walked by it. She had that . . . vibe. A weird energy of knowing things. And at the reception, it’d seemed like she’d definitely known. Or guessed.

So.

He stood in the outer hall. Peered down it at Mrs. Preston’s front door. He worked his hands into his pockets. He glanced back at his own door, which felt like looking at Nat, now that she seemed to be in the very beams of his apartment. He looked away. Twisted his hands back and forth in his pockets. Dug his cheek into his shoulder, itching the old scab from the piano shard.

What exactly was he going to say to her? How precisely did he think she could help him? How could Mrs. Preston help Nat, furthermore? Did she need to “move on,” whatever that meant? What if Mrs. Preston thought he was crazy? What if he . . . What if he was?

He shook that thought away. Useless at this point. He was in too deep.

He stood there. His hands twisted harder. Faster. The cheek scab itched. With each second, the hallway grew longer.

“Fuck it,” he muttered. And he marched down the hall.

* * *

The whole thing came tumbling out in jagged starts and stops, almost as soon as she opened the door. He stammered his way through the explanation of the piano and the light. He skipped over some parts that seemed more insane than others. But he was also describing his wife’s ghost inhabiting his apartment, so what sounded insane versus what didn’t felt like kind of a toss-up. The more he talked, the more self-conscious he felt. As he spoke, his hands never left his pockets.

Mrs. Preston listened to the whole thing, face twitching between confusion, concern, and something else. She smiled at him as he rambled, babble coming out of him in one long stream.

“And I feel,” he finished, at last, “that she’s just . . . spaced out. Stretched. That her . . . I don’t know, the spirit? Has just expanded into the whole place. Instead of being in her. And . . . well . . .”

He stopped. Something he’d said had made Mrs. Preston’s eyes light up. They danced over him. He wasn’t sure how to take that. Almost backed away from her.

She knew, he decided.

“It’s funny you use that word,” she said. “Expanded.”

Gil shrugged. “It’s how I feel. Er—”

“You think it’s how she feels?”

“Of course,” he said. “And, and confused. Lost. I know her, I can feel it.” The words were more high-pitched, more desperate than he expected. His cheeks burned. What am I saying?

But Mrs. Preston just nodded. Grinned wide.

“One moment,” she said.

She shuffled away into her apartment, leaving the door open. Gil stood there. His mind railed at him. Called him stupid, told him to go back to his cage and hide with the dead. What did he think he was doing here? Bothering an old, kind woman with his bullshit.

He was just about to stalk shamefully back down the hall when Mrs. Preston returned, still grinning. She held her hands tight to her chest. Whatever she was holding, Gil couldn’t see it.

She leaned against the jamb. Sighed. Closed her eyes for a moment. Ran her thumbs in circles around the thing in her hands.

“My husband,” she started. Stopped. Swallowed some sharp stab of tears. She tried again, voice stronger this time. “My husband. When he died, I didn’t know what to do with myself.”

Mr. Preston was a somewhat nebulous entity to Gil. From what he’d gathered, the man had died about two years before Gil and Nat moved in. She’d mentioned him once or twice, but no more than a passing mention.

Gil stood a little straighter, alert.

“And, apparently,” she continued, “he didn’t know what to do either. Because he never left.”

The bottom of Gil’s stomach opened.

“I never knew,” he said.

“Oh, yes,” said Mrs. Preston. “His spirit was still with me. And in such pain . . . I knew I wasn’t ready to move on. But I could feel he wasn’t ready, either. Because of me. I could feel it through the walls. And whenever he made himself known, whether it was just a little sign or a feeling I got, I could tell that he was still there because he was worried I wouldn’t be okay alone.”

Gil’s eyes flicked down to her hands.

“We were both hurting,” she went on. “But then a friend gave me this.”

Her fingers blossomed and revealed the thing she’d been hiding. A business card. She held it out to him, delicately, in both hands. To be offered, so ceremoniously, something so simple and secular made Gil suddenly uneasy. He gave her a dubious look. He removed a hand from his pocket, slow, and took the card from her. It was grimy, mostly blank. Looked almost homemade. Nothing on it but a number, in deep, black font. And a name. Gil turned it over, expecting more on the back. There wasn’t any.

“I don’t get it,” he said.

“He helps people,” said Mrs. Preston. Her eyebrows yanked themselves up and down, confidential. Her head trembled. As if passing on this knowledge excited but exhausted her. Drained her of some old burden.

Gil looked down again at the card. Its edges frayed. Dark brown spots. Passed between dozens of hands over dozens of years.

Just a number. And a name.

He tried to hand it back to her. “I don’t need a therapist.”

She shook her head, put her hands up, palms out. “No, no. You misunderstand. He isn’t . . . He’s a kind of healer.”

The card lingered in the air between them. Once he realized he was stuck with it, Gil allowed himself to draw it back in. It felt heavier than it had a few seconds ago.

“He helped me understand,” she explained, “that when people die, their spirits expand. Swell out of the body into the air. To be part of everything without being bound. That’s the beauty of being released after death. But if they feel . . . unfinished, people get stuck. Halfway. They . . . echo back. These echoes aren’t contained in bodies anymore, of course, so they become tethered to a specific place. Like your apartment. Sometimes an object, like a mirror. And they sort of . . . bounce around in there, in that loose, expanded state, instead of swelling into the air and being free. It’s hard. But this man.” She wagged a finger at the card. “He helps set them free. That’s where my husband has gone now.”

“Gone,” said Gil. It was the only word that really stood out.

She nodded. “But gone where he’s a part of everything, like he’s supposed to be. Gone to . . . a better place.”

“Ah-huh.” Gil stared at the card. It grew heavier. “Well, thanks,” he said. Immediately he hated himself for sounding disingenuous. “I mean, really. Thank you. I’ll . . . I’ll give him a try.”

She grinned again. He tried not to look at her teeth, realizing just how gray they were. “Do. He helps. He’ll help your wife find her way.”

“Right. No, I appreciate it. I’ll give you the card back after I call him?”

“Oh, no. I don’t need it anymore. It’s yours.” With that, she waved, wished him good luck, and shut the door. A waft of incense puffed out after her. He coughed.

Gil remained for several seconds, until he heard the chain slide on the other side of the door, and he figured it was probably time to walk back down the hall. The entire way, he held the card out in front of his chest. Stiff. As if it were on fire.

Nothing there. Except a number. And a name.

When he got home, it took him ten nervous minutes, one hand holding the card, the other turning in his pocket, to finally take out his phone and dial the number.

It rang twice.

When the line connected, he heard a cough. The crack-rustle of moving leather. Then a voice. Low and thick, like the drone of a distant lawn mower: “Hector Brim. Help you.”

Gil swallowed. This was not the voice he’d expected. It did not feel safe. It did not feel helpful. It felt, instead, like someone had stretched rubber bands across his limbs and now tugged them hard. He wanted to hang up, and curl in on himself.

“Hello,” he managed. “My name is, uh, Gil. I have a, a problem.”

“Most people do.”

This threw him off. “It’s . . . Ah-huh. Right. Well. I got this card from a friend. I . . . It’s my wife. She—”

“When did she pass?”

Again, Gil was taken aback. The voice hadn’t skipped a beat. No preamble. No explanations. The blank simplicity of the card made itself felt here, too. This man knew what he was about.

“About a month ago,” he said.

“Recent.”

A pause. Gil’s grip on the phone tightened. He wasn’t sure if he was supposed to say something or if the man on the other end was thinking. He pictured the voice out there, what its owner looked like. Saw him sitting in shadow, draped over an armchair in a corner somewhere. Nothing but stillness and dark. He realized how opposite this was of what he had expected and—

The voice broke in on him: “Your address?”

Numb, Gil could think of nothing else to do other than to give it to him.

“Mm. Been there before.”

“Yes. Um. Mrs. Preston. She gave me your card.”

“Not much for names.”

Another pause. Gil winced.

“So,” he said.

“Alright. Three hours work for you?”

“Three . . . Sorry, three hours from now?”

“Mm.”

“I.” Gil cleared his throat. “Yes. Sorry. Yes. That works.”

“Be four hundred.”

“Sorry, dollars?”

The line went dead.

Gil began to pace, heart and mind racing. Eventually, he landed on the couch in the living room. Tucked his knees up under his chin. Coiled himself there, tight and anxious. He wondered what he was supposed to do for three hours. Knew he would do nothing but sit.

Regret flooded him.

A better place . . . Christ, that’s . . . What is that? What a fucking cliché. That might be all well and good for Mr. Preston, but whatever that “better place” was, Natalie would be gone. And suddenly, he wasn’t so sure he wanted that. Even if it meant hurting her, he wanted her to stay. Because if she left, he’d be totally, completely alone.

He thought about asking the light in the hall for her opinion, but he was afraid to know the answer.

No. He knew. And he knew he knew. This was the right thing to do. He was just scared, that was all.

So he sat. Waiting. His entire body throbbing.

Finally, he got up and wrote a check to Hector Brim.

* * *

When Hector Brim was young, he moved to the city because he wanted to feel connected to everything. All the voices and echoes he could possibly hear. He’d brought with him his bag of Brim family tricks. The tricks were old, but new to him and exciting. For the most part. There had been a few that, for the several years his father trained him, passing on his inheritance, Hector had never really liked or understood.

For example, the brand.

“Doesn’t it hurt?” Hector asked once, when he was nine.

“This tool is for angry, violent spirits,” his father explained. “Ones beyond our help, and in need of control.”

“But they’re people, too.”

“Everybody is people, too.”

“So we should help everybody.”

His father smiled. A limp, tired thing. “You can try. That’s all this family has done, for nearly fifty years. Try . . . Come, let’s keep practicing. Hold the brand to the light again. Your form needs improvement.”

When Hector moved to the city, he rented a small apartment in Chinatown, and everything was magic. This was back when he was really helping people, and the irises of his eyes were sunlight on leaves. He looked through these bright green eyes at his new apartment, beaming. They shone as he thought of all those echoes, all the people there to help. All around him, in the tall glittering of the city.

It was a bright time. Being young.

But the more time he spent in that apartment—the more he listened to the radiator’s metallic tattoo, the scurry of rat-feet on floorboards, the couple upstairs who fought and broke things, and the alley downstairs where people screamed at two a.m.—the smaller it felt. More cramped. More lonely.

Jobs poured in. Word of mouth. People desperate. Seeking closure. Seeking help. Seeking proof of Something More.

He kept doing it, dealing out his family tricks like candy. But the high lessened every time. For a while, he kept bringing the stones to the shore every time he used the box for a job. Kept dumping the stones into the brine and trying to feel good about it all. Trying. He even tried to feel good about the times he had to use the more violent tricks, like the brand.

But something held him back.

One day, before he brought the latest stone to the beach, Hector gazed out his one small window at the afternoon. He held the stone in his hand, soaking in its warmth and company, the voice inside. He always liked to sit with them like that. Just for a little while. The company was good, for what it was. The sun gleamed against all that glass stuck up in the sky. He tried to breathe it in. Feel less cramped. Tried to press his palm against the window and touch it all. All those people . . .

But the family tricks don’t work that way.

His eyes landed on a face. Stuck inside another window, far across the way, gaping out at the same bleak cityscape. And seeing that, Hector realized that he wasn’t connected to anything at all. He was in a cage. His palm against the bars. That face was in its own cage. And all across the city, there was nothing at all but cage upon cage upon cage. All alone. All clanking, scurrying, fighting, breaking, mugging, fucking, crying, dying. No trick could help or stop all that. He realized this, and something inside of him began to turn. Began to bend.

He never took that last stone to the beach.

Eventually, his entire world became nothing more than the warm-metal piss-stink of a life lived in a constrictive, concrete Hell.

And that was a very long time ago.

* * *

Gil opened the door. He had to take a step back and blink. Looking at Hector Brim gave him vertigo. The doorway swam a little, and it took him a moment to steady it. The man was well past six feet tall, looming a solid foot over Gil. He was old. Tufts of dirty-snow hair cotton-balled across his head. The vertigo came not from his height but from his body, which was cracked to one side. Head lilting toward his left shoulder, and the shoulder sagging outward. It was the bag in the man’s left hand. It dragged an entire half of his body down toward the floor. A massive, black leather briefcase. Stuffed with what Gil assumed could only be bricks. The man’s eyes made Gil dizzy, too. The irises were a deep moss. Overgrown and forgotten. The man’s beige trench coat must have weighed a ton. And it was August.

The man spoke: “Gil?” That old lawn-mower groan.

“I am. Yes.” Gil stuck out his hand. Hector Brim stared at it. Gil retracted.

“Come in,” he said. “Mr. . . .”

“Just Brim.”

Brim had to duck under the doorway. He stepped into the room, feet heavy, echoing. Gil closed the door behind him. As soon as Brim entered the apartment, he locked his eyes on the ceiling. Grunted. Moved into the living room. The carcass of the piano was still in the corner, but Brim didn’t even glance at it. He moved in slow circles around the room, gazing up at the ceiling. The bag thudded against his thigh, but he seemed not to mind. He’d done this hundreds of times before. Thousands, maybe. Gil could tell.

The room was silent except for the soft pound of the bag and the flutter of the trench coat. Gil stood awkwardly by the door. Shoved his hands into the pockets of his jeans. Should he say something? Brim didn’t seem to mind the quiet, so Gil remained silent. Brim swung his head from side to side. It swung him into the hall, and his body followed it, as if the rest of his spine were only vaguely attached to his skull. A broken rag doll, Gil thought. He hesitated, then followed in Brim’s wake. When he did, he found Brim standing in the middle of the hall, staring straight up. Straight into the light fixture.

“Jesus,” Gil couldn’t stop himself from muttering. “That’s her.”

“Seems like.”

“I mean . . . You’re the real deal. Aren’t you?”

“Never heard anything to the contrary.” Brim kept his eyes on the light.

Gil became immediately aware that Nat was hiding. That she was pointedly not making herself known. She didn’t want to go. She wasn’t ready to leave him. He could feel it. His hands turned in his pockets. Anxiety tugged at those rubber bands in his arms. He shuddered.

“Woman down the hall,” said Brim.

“Um. Mrs. Preston.”

Brim grimaced. “Names . . .”

Gil wasn’t sure what he meant by that.

“She explain to you?” Brim asked. “About souls?”

“She said something about expansion? I mean, no, not really. I . . . Look—”

“Mm.” Brim lurched back into the living room. He breezed past Gil, pressing him against the wall. The bag almost rammed into Gil’s knee as he passed. Again, Gil followed. He felt stupid following this man around his apartment, but he wasn’t sure what else he was supposed to be doing.

“Souls,” said Brim. He positioned himself in the middle of the living room, and Gil felt his blood go cold. Brim stood in the exact center of where the heart had been. Maybe Brim already knew that. That was probably the point.

In his pockets, Gil’s hands churned.

“When our bodies release them,” Brim continued, “they spiral out into the ether.” He placed his briefcase on the floor. “Typically, they go elsewhere. Don’t know much about that.” He undid the zipper running along the top of the briefcase. Its lips yawned open. Gil could almost hear it sigh. “But if there is a lack of what you might call closure, the spirit remains. In a somewhat half-tethered, expanded state. Your wife, for instance.” The bag looked like it was choking. It gasped for air. Jaw muscles stretched tight against whatever was lodged in its throat. Gil felt it, like a living thing. He stepped back. “Your wife has expanded out of her body and has sunk herself into the very beams of your home. It is, I’m sure, uncomfortable.” Brim reached down into the gaping maw of the bag. It seemed to gag around his wrist. Gil took another step back. “What we do here is re-condense those souls. Bind them back into something more . . . solid.” Brim pulled a box out of the bag’s innards. He held it up and looked at it.

The box was an ancient thing. It had the same passed-down quality as Brim’s card. Its sides shone black from decades of hands. The small brass latch had once glittered, and now bore the dull refraction of a dying fluorescent.

Brim placed the box on the floor next to the bag. He slid open the latch, lifted the lid, let it fall back. The empty box and the stuffed bag sat next to each other, yawning at the ceiling. Trying to swallow it whole.

“The box will accomplish that,” Brim concluded. “It is a . . . powerful tool. My grandfather, Porter Brim, crafted this box when he was my age. He removed his own fingers as an offering, and used his stubs to carve this, from Renfield barnwood. Not that that means anything to you?” He gave Gil a questioning glance. Gil shook his head. “Mm. Thought not.”

Brim ambled over to the couch. Sat down with a large rush of air. He sighed. The coat settled about him. He was still.

Gil stared at him. Almost a minute passed. Brim sat motionless, hands in his lap. Eyes blank. Gil shifted side to side. Part of him wanted to grab the ax again and hack the little box apart. Silence throbbed against his ears until, finally, he burst. “Sorry, I don’t understand what’s happening.”

Brim jerked his shoulders. “Your wife will condense inside the box. I’ll take her to a place where she can be free. She’ll be ready in a minute or two.”

“Yeah, sorry, I don’t know what the fuck that means, though.” Anger curled into Gil’s voice. Brim stared at him, unmoved. Those old eyes, those twin moss-covered rocks, gaped out from their sockets.

Gil stepped forward. Took his hands out of his pockets. “Hey. What does that mean?”

Brim sighed again. Everything seemed hard to him. Everything a struggle. He seemed to drag himself through talking just like he dragged his body through space. “Look, don’t bother asking how it works, because I don’t know. Just that it does. The box draws souls inside itself. Once inside the box, they crystallize into stones. The stone reflects the true spirit of the person being condensed. Agate, pyrite, opal, amazonite, obsidian, red coral . . . Most people are quartzite.” He shook his head. “You wouldn’t believe how many people are quartzite.”

“I don’t give a shit about quartzite. I know my wife. I don’t need to see her true whatever the fuck.”

“Not about need. Happen anyway.” The final word strained as Brim stood. He unbent himself from the couch and his joints cracked. He shuffled back to the box, continuing to crack and pop along the way. He towered above the ancient, wooden thing. Peered into it.

“Ah,” he said. He stooped, reached inside.

Gil felt manic. Felt angry energy beating through his body like massive drums. He was restless and tired, and he wanted this man gone. He wanted his wife back. Wanted her to stay. Not crystallized. Fuck this.

He charged to the door, threw it open, and said, voice shaking, “You know what? This, this is done. I’m sorry. I don’t want this.”

Brim didn’t move. He kept his hand in the box.

“Hey. Did you hear me? I—”

“Tiger’s eye.”

Gil blinked. “I’m sorry?”

“Tiger’s eye.” Brim held up a gleaming honey-colored stone, about the size of his thumb.

Gil swallowed. “Where . . . where did that come from? How did you get that? What is that?” His mind rejected it. This rock was not his wife.

Brim ignored him. “Tiger’s eye is a good one. Your wife was very confident.”

Gil shook his head. “Stop.”

“She was grounded. Practical. Had an artistic streak.”

“Please stop.”

“She made you feel safe. Brought good luck.”

“I said stop.”

“Here.”

Brim strode over to Gil. He held out the stone. Eels swarmed in Gil’s stomach. He hesitated. Then gave Brim his hand. Brim placed the stone in Gil’s palm. It was warm. Felt . . . full.

“Can you feel her?” Brim asked.

Gil’s voice came from far away. “Yes.”

“Can you hear her?”

His eyes burned. He didn’t move his hand. He felt the warmth, the pulse of those ribbons of color. Tried to focus, and feel or hear anything else.

“No,” he said. His voice caught in his throat.

“I can. She has a beautiful voice. Hearing her sing must have been very special.”

Gil looked up. The man’s face remained mossy and distant.

“What are you going to do with her?” Gil asked. “I mean, how does this help her? She’s in there? Fucking . . . in there?”

“I’ll take her to the beach. Many other stones. There, she can be with the ocean and the land and everything else. Free. Connected to the entire world.”

“Oh,” said Gil. He didn’t take his eyes off the stone.

After a long time, Brim slid it from Gil’s hand. “It’s time.”

Gil felt suddenly cold and empty.

“I can take her to the beach,” he said, desperate. “Let me take her.”

Brim shook his head. “There’s another step.”

“Can I at least wa—”

“It must be done alone. It’s how the trick works.”

Gil shrank. “Oh.”

“Don’t worry. She’ll be fine. Think of it like spreading your ashes into the ocean.”

“Ah-huh. I . . . I like that.”

“Most people do.”