6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

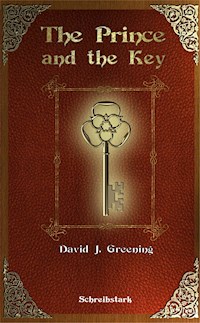

- Herausgeber: Schreibstark-Verlag

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Sprache: Englisch

Every time Kura-Kura the turtle girl could not fall asleep, her father would tell her a story...Tales of the Sun and the Moon, the Korua Raksasa, the boy who fell in love with a star or the Mango’nui, the Great White Shark. … and of course the story of the Princess and the Key.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

Inhaltsverzeichnis

The Ring and the Dragon

Kura-Kura and the Korua Raksasa

The Unicorn and the Magpie

The Boy and the Star

The Princess and the Key

The Prince and the Pearl

The Sun and the Moon

The Boar, the Crow and the Wizard

The Warrior and the Shrew

The Shepherd and the Wolf-Cub

The Knight and the Death

The Mango’nui

The Woodcutter and Lady Oak

A SchreibstarkBook

Copyright © 2016 by David J. Greening

Second edition 2020

Cover illustration by Kostas Nikellis, interior illustrations by Thanos Tsilis, cover design by Patrick Toalster & Martin Henze

kosv01.deviantart (dot) com

thanostsilis (dot) com

SCHREIBSTARK

An imprint of

Schreibstark Verlag der Debus und Dr. Kuhnecke GbR

Saalburgstraße 30

61267 Neu-Anspach

ISBN 9783946922575

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously and are not to be construed as real. Any resemblance to actual events, organisations, locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Θ

David J. Greening

The Princess and the Key

Fables, Riddles & Tales

Θ

Θ

For Henrik and Erik and Mathilda

Θ

Acknowledgements

I am deeply indebted to several people whose help was much appreciated during the writing of this book. As so often, Elmar Köhler for his commentaries and productive criticism, Christine Billek, Charlotte Knöll, Judith May, Stefanie Mertink, Nina Merget and Katha Plum for proof reading, helpful comments and input, Kostas Nikellis and Thanos Tsilis for their artwork and finally my colleague Martin Henze and my brother Patrick Toalster.

Θ

David J. Greening

The Princess and the Key

Θ

PART ONE

Beginnings

We know what we are,

But know not what we may be.

Hamlet, Act 4 Scene 5

The Ring and the Dragon

Once, there were three brothers who lived together with their father at a lake. Their mother had died early, and so it had been their father who had raised them on his own. Gabha, whose name means ‘smith’ in our tongue, was a smith who could work magic into whatever he crafted. But he had always been wary of teaching his sons either his trade or his magic, as only Mhadra, his middle son, had turned out well, while his oldest, named Brí and his youngest, called Fáinne were deceitful and full of mischief. And so, only Mhadra had learned the trade from him. Still, though he was only too well aware of their shortcomings he loved them as they were the only family he had left.

One day, Gabha went into his smithy and decided to make something special.

“Sons,” he said to the three, “today I will make something I have never made before. I need the house and the smithy to myself to work my magic.”

At this, Mhadra, nodded and left to go fishing in the lake, but Brí and Fáinne grumbled and complained at having been asked to leave.

“Can I not stay?” Fáinne, whose name means ‘he-who-encircles’, asked lazily, but his father shook his head.

“Can I help thee, father?” Brí, whose name means ‘might’ in our tongue, asked cunningly.

“Thou only wishest to learn of my magic, so thou canst put it to thine own uses,” Gabha replied, shaking his head sadly, “So I must say no to thee also. And now both leave, for this is still my house.”

“Hopefully not much longer,” Fáinne mumbled, rising.

“Only while he lives,” Brí added, and the two of them grumpily went out of the house, leaving their father to his devices.

Gabha fired up his furnace and went to work. He worked the whole morning and the entire afternoon, ceaselessly and without tiring, steadily forging and crafting. When the sun set, he was still not finished, and through all of that night he endowed his creation with powerful magic of his own making.

When the sun finally rose the next day, his work was done. He thrust his creation into a vat of water, filled with hissing, boiling water, filling the smithy with steam. When at last the metal had cooled, he held the object he had made up into the light to scrutinise it: a ring. It was a masterpiece, and Gabha knew from that moment on that whatever he made from now one would be secondary to what he had crafted through one entire day and night. The ring was perfect. Smooth and golden, it shone as if the smith had managed to incorporate the light of the sun itself into it.

Gabha took it into his hand and weighed it. It was both light and heavy at once, a golden band, beautiful in its simplicity, and still complex from the magic he had worked into it. He tried it onto several different of his fingers, and each time it fit perfectly, as if it had been made precisely for that single digit. Tired, the smith left the ring on his finger, deciding he needed to rest from his labours, and laid himself to sleep in a cot he kept nearby for precisely that purpose. Little did he know he had been observed.

“It is beautiful,” Fáinne exclaimed.

“Indeed, it is a masterpiece,” Brí agreed, nodding.

This had not been the first time their father had asked them to leave when he went to work, and so, with time, they had crafted for themselves a look-out, from where they were easily capable of keeping watch on their father’s activities. And as they set eyes on the ring, both immediately knew they had to possess it.

“I must have it,” Fáinne said, “it is perfect.”

“Indeed,” Brí, who was both craftier and more deceitful than his brother, agreed, but only in fact wished to lay his own hands on the object. “But father will never give it to either thee or me. Not as long as he lives at least.”

“He is old,” Fáinne replied, grinning nastily, “and, after all, everything dies.”

His brother grinned back in understanding, saying:

“Then maybe we should help things along.”

And so, the two brothers agreed to murder their father, so that they could possess his magical ring. Over the next week they plotted and planned, but neither had the courage to do the deed. Until one day, when Mhadra had once again gone out, Fáinne could contain his greed no longer and said:

“I will take it from him now! Thou canst either help me or not, but I will wait no longer!”

“I will help thee, brother,” Brí replied, lifting his hands in a gesture of appeasement, for he had only waited that his brother perform the deed, not wanting to sully his own hands.

“So, we are agreed then,” Fáinne said, and led the way to the smithy.

They went inside, each grabbing one of the swords that their father had crafted, and approached Gabha, who, busy pounding on his anvil, had neither heard nor seen them. Without hesitation, the youngest brother struck down his father from behind, mortally wounding him, while the older of the two stood by. As the smith lay there dying, Brí quickly turned him over to get at the ring, but found every single one of his ten fingers bare.

“He does not have it,” he cried out, immediately glaring at his brother in distrust, “you took it!”

“I did not!” Fáinne spat back, taking a better grip on his sword, “that little sneak Mhadra must have somehow got it into his fingers!”

This was in fact not far from the truth. Knowing that nothing good would come of it if either Brí or Fáinne laid hands on the ring, the smith had given it to his middle son that morning, before going to work at his forge.

“Take it to our neighbour Cúramach,” the smith had said, “he is a versed in magical lore and will put good use to it.”

And so Mhadra had set out and taken the ring, without knowing that he was obeying his father’s last wish.

“This is an object of powerful magic,” Cúramach had said when Mhadra had presented him with the gift of his father. “I will accept it, but not as a gift. I will take it as a token of thy trust and good-will.” And then seeing the way the young man looked at his daughter, he added, “Thou hast given it to me freely, without thinking of keeping it. For this I shall give you the hand of my daughter, Feírín.”

And truly, Mhadra had long since been in love with the daughter of Cúramach, but had never possessed any gift worthy of the wizard’s daughter.

“Wilt thou have this son of Gabha, Feírín?” he asked his daughter, whose name means ‘gift’ in our tongue.

“I will, father, for I have long since loved Mhadra dearly,” his daughter replied.

“So thou art mine and I am thine,” the son of the smith said, smiling.

“And so, this ring wrought with dark magic may free the two of you from thy ties and bonds,” Cúramach, whose name means ‘the-careful-one’ in our tongue, said. “But you now must leave.”

“Will I accompany Mhadra home, father?” his daughter asked, but her father shook his head.

“Can we not remain here then?” the son of the smith asked, but his father-in-law shook his head again, saying:

“This ring is a harbinger of evil. And unbeknownst to either of thee, he who is in its possession shall meet an untimely end. But not thee,” he quickly added when Mhadra looked at him with a shocked face, “for thou hast only been its bearer, and never in its possession. And now: Begone!” he ordered.

At this, Mhadra and his betrothed Feírín all of a sudden found themselves blown away, out the door, through the valley of the lake and beyond, thanks to the magic of Cúramach, the ring forever lost to either of them. They would be happy and have many children, one of whom would take the ring in his hands a final time, but that is another tale.

Just as the two had been whirled away to safety, Brí and Fáinne appeared on the door step of Cúramach’s house.

“Give us the ring,” the younger of the two brothers said menacingly, “or thou wilt regret this day,” at which Brí nodded.

“I regret it already,” Cúramach replied and took the ring from his pocket, “for nothing good will come of it.”

As he held it up, the eyes of the two brothers began to gleam with greed and hate, with lust and murderous intent. Ever the cautious one, Brí held back, while his brother stormed forwards, drawing a long, cruelly curved dirk from his belt. Without hesitation, he plunged the blade into Cúramach’s chest, instantly killing him.

“Quick, secure the other treasure,” the older brother said, moving to Fáinne’s left to avoid the knife, “I will take the ring from his finger!”

“Thou thinkest me a fool such as thyself, Brí,” the younger brother replied, “but I am not!”

Moving forward before his brother could act, he took the ring out of Cúramach’s hand and put it on. Fáinne’s grin got broader and more ferocious, while his body lengthened and grew in size. And as Brí looked on, the ring transformed his brother into a dragon.

“It is I who did the killing, so it will be me who reaps the reward!” the dragon said, its transformation still not concluded, as skin turned to scale, tooth to fang and finger to claw. “And now: begone!” the monster roared, nearly knocking Brí off his feet.

With the other choice only being to die on the spot, the older brother ran off, saving only his life. He ran until he could run no more and then some, and then stopped to look back. Smoke issued from the wizard’s house near the lake and Brí vowed to return and take the ring off the beast his brother had become, but that is another tale.

Kura-Kura and the Korua Raksasa

Once there was a girl. Her people were called the Shardana, which means ‘Sea People’ in our tongue. They lived as fishers and traders on the Peaceful Ocean, far to the east. She had lost her parents to a storm and so she had become an orphan, but though she had been fostered by many families, she had never found a proper home. And so, the girl became silent and withdrawn and her proper name, which I will not tell you because that is another story, was forgotten. Soon, everyone called her Kura-Kura, and that means ‘turtle girl’ in our tongue.

Tawhito and Tua were an old couple and had never had any children. One day, Tawhito said to his wife:

“Kura-Kura is without parents, while we are without children. This cannot be good. We should adopt her, wife.”

“She is wild, she is,” Tua replied, “and has been so for very long. Can we truly ever tame such a girl?”

“True, true, wife,” Tawhito said, thoughtfully. “We shall simply say we do not intend to tame her, but will accept her as untamed as she is. For,” he continued, “if we would love her as our own, we must let her be the person she is.”

Tua agreed and so it was done. Kura-Kura was adopted by Tawhito and Tua and became Tamaiti, which means ‘child’ in our tongue. But after losing so much, she was often afraid at night, and so her new father told her stories. Tamaiti’s favourite was the tale of the Korua Raksasa.

“Can you not sleep, Tamaiti?” Tawhito would say to her.

“No, ayah,” she would answer. “Will you tell me a story?”

Her father would sigh, pretending to be busy, tired or both. But then he would always sit down beside her and begin telling her a story.

“At the beginning of time,” he would say, “there was only the sea, Kete-Tamaiti,” which meant ‘my little child’ in our tongue. “And the creatures of the sea were alone in the world, without a sky above them, or a sun to shine down and give them light.”

“Was there any dryland?” she asked, speaking the words as one, as land was of course invariably dry from the point of view of the Shardana.

“No,” Tawhito replied, “in the beginning there was not.”

“And were there people, were there Shardana, ayah?” she asked, and ayah means ‘father’.

“Not like us, Tamaiti, no. But there were other people, people who did not know about the sun or the sky. And they lived in the sea. Similar to us, but not like us,” he said, and Tamaiti would nod seriously. “And then, one day these people decided to kill the largest and most dangerous beast in the sea.”

“The Korua Raksasa,” Tamaiti would say, sinking deeper into her blanket.

“Exactly,” her father answered.