Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: IVP

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Serie: The IVP Signature Collection

- Sprache: Englisch

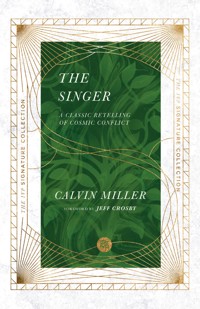

- Over 400,000 Copies in Print "In the beginning was the song of love." In this timeless classic, Calvin Miller retells the story of Jesus through an allegorical poem about a Singer whose song could not be silenced. Since it was first published in 1975, The Singer has left an indelible impression on Christian literature and offered believers and seekers the world over a deeply personal encounter with the gospel. With a new foreword by IVP Publisher Jeffrey Crosby and an updated interior design, The Singer is now available as part of the IVP Signature Collection, which features special editions of iconic books in celebration of the seventy-fifth anniversary of InterVarsity Press. Now there's also a companion Bible study guide available with eight sessions exploring the characters in the text.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 87

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Some memories lodge themselves in our hearts and minds, standing ready for recall on a moment’s notice.

Thirty-eight summers ago when I joined my soon-to-be-wife, Cindy, for her family’s vacation in the north woods of Wisconsin, I took along a slim, oddly shaped book she had given me titled The Singer. It was written by Calvin Miller, a man I’d never heard of, and it had mesmerizing sketches scattered throughout its pages, which added a mysterious, evocative texture to the poetic prose. Together the words and images drew me in, captivating my attention to an unusual degree.

As the aging blue Chevy van rumbled its way north for hours on end through the Midwestern farmlands of the United States, I read Miller’s retelling of the Christ of the Gospel of Matthew, written in the narrative tradition of J. R. R. Tolkien and C. S. Lewis, two writers I had heard of but whose works I had not yet read. That would come later, influenced by the impact and enjoyment of The Singer (originally published in 1975) and its sequels, The Song (1977) and The Finale (1979), no doubt.

When I opened the cover of The Singer on that summer morning as our journey began, I found the opening words were situated not in a customary location but rather on the bottom left-hand side of the page, with type set in a manner not like a normal book but rather like poetry:

For most who live,

hell is never knowing

who they are.

The Singer knew and

knowing was his torment.

Like the opening lines of a Susan Howatch mystery novel, Calvin Miller had me hooked from line one of The Singer.

My reading tastes in that summer of 1982 were decidedly tilted toward twentieth-century history and biography, most frequently those that told the stories of sports legends. Literature of the imaginative and the biblical variety were not yet on my radar to a significant degree.

The Singer changed that. It also changed my life.

The excellence of the writing and the spiritual impact of the story found in The Singer were touchstones on a spiritual and vocational journey that took me into the ministry of Christian bookselling in 1983 and, for more than two decades, Christian publishing at InterVarsity Press.

In his memoir, Life Is Mostly Edges (Thomas Nelson, 2008), Calvin Miller shared the unlikely story of this most unlikely of IVP books.

At the time of its writing, Miller was a young pastor of a small church that was not growing. He was also the author of two or three books that had not sold well. He joked that his mother was buying most of the copies that did sell and donating them to church libraries. He felt a sense of failure and despair. He worried about providing for his family.

In the midst of his despair, he saw the rock opera Jesus Christ Superstar—a format he enjoyed, but it portrayed, he said, “a very weak Jesus.”

“I wondered why nobody had written of a more robust Jesus, who knew who he was and how he could strengthen his disciples with all they needed for the tough times,” Miller wrote.

Calvin posed his question to a friend named Bob Friezen, a fellow pastor in Omaha, who agreed that such a portrait of Jesus should be written.

“That’s a good idea—a more robust Christ! It’s such a good idea,” Friezen said. “Why don’t you do it?”

Not long after, it happened. It was two o’clock in the morning.

Miller writes in Life Is Mostly Edges, “I heard no voice, but some words leapt to the front of my mind. The words were, ‘When he awoke, the song was there.’ I had no idea why the line came to me, but I have learned to serve my poetic psychoses. So I went to my study and wrote down the words. In fact, I wrote down several pages of words” (p. 261).

Miller called that “The Night of the Singer.”

And the words flowed night after night until it was finished.

After it was turned down by a larger publishing house in Waco, Texas, Miller sent the manuscript to InterVarsity Press and its editorial director, James W. Sire. The Singer was a good book and ought to be published, Sire told Miller in his letter of response. Yet as Miller recounts in the preface to the 25th Anniversary Edition, Sire qualified that IVP might be left with four thousand unsold copies “on skids in our basement.”

Those skids did not last long.

The reception The Singer received upon its release in June of 1975 was positive, indeed. The next month, Miller filled a slot at the Christian Booksellers Association (CBA) annual convention in Anaheim, California, taking the place of IVP author Paul Little, who had tragically been killed in an automobile accident earlier in the year. Miller spoke at a luncheon bookended by Catherine Marshall, author of the novels Christy and Something More, and by Johnny Cash, in Anaheim to promote his book Man in Black.

Years later, Calvin Miller would serve on a panel I moderated at the American Booksellers Association (ABA) annual convention in New York City on “The Power of Story,” and a friendship was born that lasted until he passed away unexpectedly in 2012.

“Nobody writes them, not really. Stories just tell themselves,” Miller said. “We who take the credit for them listen to them as they pass us by, and we have the moxie to write them down.”

Michael Card, a musician and author, spoke for many readers of The Singer when for its 25th Anniversary Edition he wrote, “The Singer was not simply a book for me. It was an event. It was the first demonstration in our time that the gospel could be newly presented to the world at the level of the imagination.”

On February 1, 2001, I sat with Calvin Miller in a café in Dallas, Texas, where I had invited him to come for a book industry conference to promote the 25th Anniversary Edition of The Singer. We talked about our respective lives and hopes, but most of our talk centered on the surprising impact of that book he authored—the impact on him, on me, on readers worldwide.

He placed his signature on my copy of the anniversary edition that day. It is one of my most cherished keepsakes from a life spent working with books.

I’m grateful to my colleagues at InterVarsity Press for releasing this IVP Signature Collection edition of The Singer. I have no doubt that Calvin Miller would be pleased to know the book is still telling a magical story of a robust Christ “who knew who he was and how he could strengthen his disciples.”

In the 1960s the rock culture savior made his appearance in New York. Jesus Christ Superstar and Godspell opened on Broadway. Before long these musicals had entered common culture all across America. The tunes were memorable, and here and there the lyrics touched the New Testament account of Christ. Still, to me the Broadway Jesus seemed a pale imitation of the New Testament Christ. Someone, I thought, ought to write a creative account of the Christ of St. Matthew that St. Matthew would recognize. It was then that the chilling notion occurred to me: perhaps I was the one to do it.

It occurred to me that God might be giving me what Peter Marshall once called the tap on the shoulder. Yet the idea that I might do it was so grandiose that I pushed the matter to the back of my mind and left it there. I might never have attempted the writing of such a piece except that during those days I was going through some tough times spiritually. I had been trying to plant a new church in the suburbs of Omaha. The effort of making it all happen seemed futile at times. So few were actually attending the church that my stamina was spent. I often felt spiritually bankrupt. I was plagued by feelings of discouragement that sometimes bordered on depression. In my emotional neediness I turned to Christ each day for the supply of grace I needed just to survive.

In my hunger to find the nourishing of Christ, I found myself eagerly devouring the devotional classics. Teresa of Ávila, Thomas Merton, and a score of other writers came to my rescue, and their counsel, coupled with that of Scripture, at last gave vigor to my feeble emotions. During those days the weak witness of the Broadway Jesus met the robust Christ of Thomas á Kempis at last. In the middle of my neediness I was rescued by the Singer.

I first met him one morning at 2:00 a.m. I awoke and hurried to my study. The energy of his arrival came in a poetic visitation. I sat down and wrote in longhand, “When he awoke, the song was there . . .” It was an odd autobiographical incident, for when I awoke the song had been there, but more than that, the Singer was there. My unsteady state of mind had summoned a Christ more real than the Lloyd-Webber Jesus. That superstar was too interested in the footlights of Broadway to offer me much help.

On alternate nights thereafter, I awoke, went to my study and continued to write. Gradually the story took shape as a tale of light breaking through a half-dozen midnights of my hungry spirituality.

On one of those postmidnight visitations as I returned to my bed, my wife awoke and asked me what I was doing.

“Writing a poem about Jesus,” I replied.

“It must be a long one,” she said.

“Yes, it may be 150 pages when I’m done,” I said in the darkness.

“But you haven’t been able to sell even a short poem anywhere in the country.”

“I know. Do you think I could be going crazy?” I probed.

Used to my poetic insomnia, she replied, “No, honey. People like you never go crazy; they just drive the rest of us there.”