2,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Ale.Mar.

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Contents Author's Note PART THE FIRST Chapter 1. The Suit Chapter 2. The Crossing Chapter 3. Good-Bye, Simon Chapter 4. The Great Upheaval Chapter 5. Virgin Soil Chapter 6. Triumph Chapter 7. Lynx-Eye Chapter 8. On The War-Path PART THE SECOND Chapter 1. Inside The Wreck Chapter 2. Along The Cable Chapter 3. Side By Side Chapter 4. The Battle Chapter 5. The Chief's Reward Chapter 6. Hell On Earth Chapter 7. The Fight For The Gold Chapter 8. The High Commissioner For The New Territories

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

AUTHOR'S NOTE

PART THE FIRST

CHAPTER I THE SUIT

CHAPTER II THE CROSSING

CHAPTER III GOOD-BYE, SIMON

CHAPTER IV THE GREAT UPHEAVAL

CHAPTER V VIRGIN SOIL

CHAPTER VI TRIUMPH

CHAPTER VII LYNX-EYE

CHAPTER VIII ON THE WAR-PATH

PART THE SECOND

CHAPTER I INSIDE THE WRECK

CHAPTER II ALONG THE CABLE

CHAPTER III SIDE BY SIDE

CHAPTER IV THE BATTLE

CHAPTER V THE CHIEF'S REWARD

CHAPTER VI HELL ON EARTH

CHAPTER VII THE FIGHT FOR THE GOLD

CHAPTER VIII THE HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR THE NEW TERRITORIES

THE THREE EYES THE EIGHT STROKES OF THE CLOCK

"You don't regret anything, Isabel?" he whispered.

THE TREMENDOUS EVENT

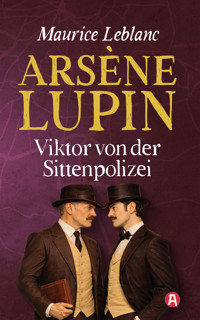

BY MAURICE LE BLANC

TRANSLATED BYALEXANDER TEIXEIRA de MATTOS

NEW YORK THE MACAULAY COMPANY

COPYRIGHT, 1922, BY THE MACAULAY COMPANY

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

AUTHOR'S NOTE

The tremendous event of the 4th. of June, whose consequences affected the relations of the two great Western nations even more profoundly than did the war, has called forth, during the last fifty years, a constant efflorescence of books, memoirs and scientific studies of truthful reports and fabulous narratives. Eye-witnesses have related their impressions; journalists have collected their articles into volumes; scientists have published the results of their researches; novelists have imagined unknown tragedies; and poets have lifted up their voices. There is no detail of that tragic day but has been brought to light; and this is true likewise of the days which went before and of those which came after and of all the reactions, moral or social, economic or political, by which it made itself felt, throughout the twentieth century, in the destinies of the world.

There was nothing lacking but Simon Dubosc's own story. And it was strange that we should have known only by reports, usually fantastic, the part played by the man who, first by chance and then by his indomitable courage and later still by his clear-sighted enthusiasm, was thrust into the very heart of the adventure.

To-day, when the nations are gathered about the statue over-looking the arena in which the hero fought, does it not seem permissible to add to the legend the embellishment of a reality which will not misrepresent it? And, if it is found that this reality trenches too closely upon the man's private life, need we object?

It was in Simon Dubosc that the western spirit first became conscious of itself and it is the whole man that belongs to history.

PART THE FIRST

The Tremendous Event

CHAPTER I THE SUIT

"Oh, but this is terrible!" cried Simon Dubosc. "Edward, just listen!"

And the young Frenchman, drawing his friend away from the tables arranged in little groups on the terraces of the club-house, showed him, in the late edition of the Argus, which a motorcyclist had just brought to the New Golf Club, this telegram, printed in heavy type:

"Boulogne, 20 May.—The master and crew of a fishing-vessel which has returned to harbour declare that this morning, at a spot mid-way between the French and English coasts, they saw a large steamer lifted up by a gigantic waterspout. After standing on end with her whole length out of the water, she pitched forward and disappeared in the space of a few seconds.

"Such violent eddies followed and the sea, until then quite calm, was affected by such abnormal convulsions that the fishermen had to row their hardest to avoid being dragged into the whirlpool. The naval authorities are sending a couple of tugs to the site of the disaster."

"Well, Rolleston, what do you think of it?"

"Terrible indeed!" replied the Englishman. "Two days ago, the Ville de Dunkerque. To-day another ship, and in the same place. There's a coincidence about it. . . ."

"That's precisely what a second telegram says," exclaimed Simon, continuing to read:

"3. O. p. m.—The steamer sunk between Folkestone and Boulogne is the transatlantic liner Brabant, of the Rotterdam-Amerika Co., carrying twelve hundred passengers and a crew of eight hundred. No survivors have been picked up. The bodies of the drowned are beginning to rise to the surface.

"There is no doubt that this terrifying calamity, like the loss of the Ville de Dunkerque two days ago, was caused by one of those mysterious phenomena which have been disturbing the Straits of Dover during the past week and in which a number of vessels were nearly lost, before the sinking of the Brabant and the Ville de Dunkerque."

The two young men were silent. Leaning on the balustrade which runs along the terrace of the club-house, they gazed beyond the cliffs at the vast circle of the sea. It was peaceful and kindly innocent of anger or treachery; its near surface was crossed by fine streaks of green or yellow, while, farther out, it was flawless and blue as the sky and, farther still, beneath the motionless cloud, grey as a great sheet of slate.

But, above Brighton, the sun, already dipping towards the downs, shone through the clouds; and a luminous trail of gold-dust appeared upon the sea.

"La perfide!" murmured Simon Dubosc. He understood English perfectly, but always spoke French with his friend. "The perfidious brute: how beautiful she is, how attractive! Would you ever have thought her capable of these malevolent whims, which are so destructive and murderous? Are you crossing to-night, Rolleston?"

"Yes, Newhaven to Dieppe."

"You'll be quite safe," said Simon. "The sea has had her two wrecks; she's sated. But why are you in such a hurry to go?"

"I have to interview a crew at Dieppe to-morrow morning; I am putting my yacht in commission. Then, in the afternoon, to Paris, I expect; and, in a week's time, a cruise to Norway. And you, Simon?"

Simon Dubosc did not reply. He had turned toward the club-house, whose windows, in their borders of Virginia creeper and honeysuckle, were blazing with the sun. The players had left the links and were taking tea beneath great many-coloured sunshades planted on the lawn. The Argus was passing from hand to hand and arousing excited comments. Some of the tables were occupied by young men and women, others by their elders and others by old gentlemen who were recuperating their strength by devouring platefuls of cake and toast.

To the left, beyond the geranium-beds, the gentle undulations of the links began, covered with turf that was like green velvet; and right at the end, a long way off, rose the tall figure of a last player, escorted by his two caddies.

"Lord Bakefield's daughter and her three friends can't take their eyes off you," said Rolleston.

Simon smiled:

"Miss Bakefield is looking at me because she knows I love her; and her three friends because they know I love Miss Bakefield. A man in love is always something to look at; a pleasant sight for the one who is loved and an irritating sight for those who are not."

This was spoken without a trace of vanity. For that matter, no man could have possessed more natural charm or displayed a more alluring simplicity. The expression of his face, his blue eyes, his smile and something personal, an emanation compounded of strength and suppleness and healthy gaiety, of confidence in himself and in life, all contributed to give this peculiarly favoured young man a power of attraction to whose spell the onlooker readily surrendered.

Devoted to out-door games and exercises, he had grown to manhood with those young postwar Frenchmen who made a strong point of physical culture and a rational mode of life. His movements and his attitudes alike revealed that harmony which is developed by a logical training and is still further refined, in those who comply with the rules of a very active intellectual existence, by the study of art and a feeling for beauty in all of its forms.

For him, indeed, as for many others, liberation from the lecture-room had not meant the beginning of a new life. If, by reason of a superfluity of energy, he was impelled to give much of his time to games and to attempts at establishing records which took him to all the running-grounds and athletic battle-fields of Europe and America, he never allowed his body to take precedence of his mind. Every day, come what might, he set apart the two or three hours of solitude, of reading and meditation, which the intellect requires for its nourishment, continuing to learn with the enthusiasm of a student who is prolonging the life of the school and university until events compel him to make a choice among the paths which he has opened up for himself.

His father, to whom he was bound by ties of the liveliest affection, was puzzled:

"After all, Simon, what are you aiming at? What's your object?"

"I am training."

"For what?"

"I don't know. But an hour strikes for each of us when we must be fully prepared, well equipped, with our ideas in good order and our muscles absolutely fit. I shall be ready."

And so he reached his thirtieth year. It was at the beginning of that year, at Nice, through Edward Rolleston, that he made Miss Bakefield's acquaintance.

"I am sure to see your father at Dieppe," said Rolleston. "He will be surprised that you haven't returned with me, as we arranged last month. What shall I say to him?"

"Say that I'm stopping here a little longer . . . or no, don't say anything. . . . I'll write to him . . . to-morrow perhaps . . . or the day after. . . ."

He took Rolleston's arm:

"Tell me, old chap," he said, "tell me. If I were to ask Lord Bakefield for his daughter's hand, what do you think would happen?"

Rolleston appeared to be nonplussed. He hesitated and then replied:

"Miss Bakefield's father is a peer, and perhaps you don't know that her mother, the wonderful Lady Constance, who died some six years ago, was the grand-daughter of a son of George III. Therefore she had an eighth part of blood royal running in her veins."

Edward Rolleston pronounced these words with such unction that Simon, the irreverent Frenchman, could not help laughing:

"The deuce! An eighth! So that Miss Bakefield can still boast a sixteenth part and her children will enjoy a thirty-second! My chances are diminishing! In the matter of blood royal, the most that I can lay claim to is a great-grandfather, a pork-butcher by trade, who voted for the death of Louis XVI.! That doesn't amount to much!"

He gave his friend a gentle push:

"Do me a service. Miss Bakefield is alone for the moment. Keep her friends engaged so that I can speak to her for a minute or two: I shan't be longer."

Edward Rolleston, a friend of Simon's who shared his athletic tastes, was a tall young man, too pale, too thin and so long in the back that he had acquired a stoop. Simon knew that he had many faults, including a love of whisky and the habit of haunting private bars and living by his wits. But he was a devoted friend, in whom Simon was conscious of a genuine and loyal affection.

The two men went forward together. Miss Bakefield came to meet Simon, while Rolleston accosted her three friends.

Miss Bakefield wore an absolutely simple wash frock, without any of the trimmings that were then the fashion. Her bare throat, her arms, which showed through the muslin of her sleeves, her face and even her forehead under her hat were of that warm tint which the skin of some fair-haired women acquires in the sun and the open air. Her eyes were almost black, flecked with glittering specks of gold. Her hair, which shone with metallic glints, was dressed low on the neck in a heavy coil. But these were trivial details which you noted only at leisure, when you had in some degree recovered from the glorious spectacle of her beauty in all its completeness.

Simon had not so recovered. He always paled a little when he met Miss Bakefield's eyes, however tenderly they rested on him.

"Isabel," he said, "are you determined?"

"Quite as much as yesterday," she said, smiling; "and I shall be still more so to-morrow, when the moment comes for action."

"Still. . . . We have known each other hardly four months."

"Meaning thereby? . . ."

"Meaning that, now that we are about to perform an irreparable action, I invite you to use your judgment. . . ."

"Rather than listen to my love? Since I first loved you, Simon, I have not been able to discover the least disagreement between my judgment and my love. That's why I am going with you to-morrow morning."

"Isabel!"

"Would you rather that I left to-morrow night with my father? On a voyage lasting three or four years? That is what he proposes, what he insists upon. It's for you to choose."

While they exchanged these serious words, their faces displayed no trace of the emotion which thrilled the very depths of their beings. It was as though, in being together, they experienced that sense of happiness which gives strength and tranquillity. And, as the girl, like Simon, was tall and bore herself magnificently, they received a vague impression that they were one of those privileged couples whom destiny selects for a life more strenuous, nobler and more passionate than the ordinary.

"Very well," said Simon. "But let me at least appeal to your father. He doesn't know. . . ."

"There is nothing he doesn't know, Simon. And it is precisely because our love displeases him and displeases my step-mother even more that he wants to get me away from you."

"I insist on this, Isabel."

"Speak to him, then, Simon, and, if he refuses, don't try to see me to-day. To-morrow, a little before twelve o'clock, I shall be at Newhaven. Wait for me by the gangway of the steamer."

He had something more to say:

"Have you seen the Argus?"

"Yes."

"You're not frightened of the crossing?"

She smiled. He bowed over her hand and kissed it and said no more.

Lord Bakefield, a peer of the United Kingdom, had been married first to the aforesaid great-grand-daughter of George III. and secondly to the Duchess of Faulconbridge. He was the owner, in his own right or his wife's, of country-houses, estates and town properties which enabled him to travel from Brighton to Folkestone almost without leaving his own domains. He was the distant player who had lingered on the links; and his figure, now less remote, was appearing and disappearing according to the lay of the ground. Simon decided to profit by the occasion and to go to meet him.

He set out resolutely. In spite of the young girl's warning and though he had learnt, from her and from Edward Rolleston, something of Lord Bakefield's true character and of his prejudices, he was influenced by the memory of the cordial welcome which Isabel's father had invariably accorded him hitherto.

This time again the grip of his hand was full of geniality. Lord Bakefield's face—a round face, too fat for his thin and lanky body, too florid and a little commonplace, though not lacking in intelligence—lit up with satisfaction.

"Well, young man, I suppose you have come to say good-bye? You have heard that we are leaving?"

"I have, Lord Bakefield; and that is why I should like a few words with you."

"Quite, quite! You have my attention."

He bent over the tee, building up, with his two hands, a little mound of sand on whose summit he placed his ball; then, drawing himself up, he accepted the brassy which one of his caddies held out to him and took his stand, perfectly poised, with his left foot a little advanced and his knees very slightly bent. Two or three trial swings, to assure himself of the precise direction; a second's reflection and calculation; and suddenly the club swung upwards, descended and struck the ball.

The ball flew through the air and suddenly veered to the left; then, curving to the right after passing a clump of trees which formed an obstacle to be avoided, it fell on the putting-green at a few yards' distance from the hole.

"Well done!" cried Simon. "A very pretty screw!"

"Not so bad, not so bad," said Lord Bakefield, resuming his round.

Simon did not allow himself to be disconcerted by this curious method of beginning an interview and broached his subject, without further preamble:

"Lord Bakefield, you know who my father is, a Dieppe ship-owner, with the largest merchant-fleet in France. So I need say no more on that side."

"Capital fellow, M. Dubosc," said Lord Bakefield, approvingly. "I had the pleasure of shaking hands with him at Dieppe last month. Capital fellow."

Simon continued, delightedly:

"Let us consider my own case. I'm an only son. I have an independent fortune from my poor mother. When I was twenty, I crossed the Sahara in an aeroplane without touching ground. At twenty-one, I made the record for the running mile. At twenty-two, I won two events at the Olympic Games: fencing and swimming. At twenty-five, I was the world's champion all-round athlete. And mixed up with all this was the Morocco campaign: four times mentioned in dispatches, promoted lieutenant in the reserve, awarded the military medal and the medal for saving life. That's all. Oh no, I was forgetting: licentiate in letters, laureate of the Academy for my essays on the Grecian ideal of beauty. There you are. I am twenty-nine years of age."

Lord Bakefield looked at him with the tail of his eye and murmured:

"Not bad, young man, not bad."

"As for the future," Simon continued, without waiting, "that won't take long. I don't like making plans. However, I have the offer of a seat in the Chamber of Deputies at the coming elections, in August. Of course, politics don't much interest me. But after all . . . if I must. . . . And then I'm young: I shall always manage to get a place in the sun. Only, there's one thing . . . at least, from your point of view, Lord Bakefield. My name is Simon Dubosc. Dubosc in one word, without the particule . . . without the least semblance of a title. . . . And that, of course. . . ."

He expressed himself without embarrassment, in a good-humoured, playful tone. Lord Bakefield, the picture of amiability, was quite imperturbed. Simon broke into a laugh:

"I quite grasp the situation; and I would much rather give you a more elaborate pedigree, with a coat-of-arms, motto and title-deeds complete. Unfortunately, that's impossible. However, if it comes to that, we can trace back our ancestry to the fourteenth century. Yes, Lord Bakefield, in 1392, Mathieu Dubosc, a yeoman in the manor of Blancmesnil, near Dieppe, was sentenced to fifty strokes of the rod for theft. And the Duboscs went on valiantly tilling the soil, from father to son. The farm still exists, the farm du Bosc, that is du Bosquet, of the clump of trees. . . ."

"Yes, yes, I know," interrupted Lord Bakefield.

"Oh, you know," repeated the younger man, somewhat taken back.

He intuitively felt, by the old nobleman's attitude and the very tone of the interruption, the full importance of the words which he was about to hear.

And Lord Bakefield continued:

"Yes, I happen to know. . . . When I was at Dieppe last month, I made a few inquiries about my family, which sprang from Normandy. Bakefield as you may perhaps not be aware, is the English corruption of Bacqueville. There was a Bacqueville among the companions of William the Conqueror. You know the picturesque little market-town of that name in the middle of the Pays de Caux? Well, there is a fourteenth-century deed in the records at Bacqueville, a deed signed in London, by which the Count of Bacqueville, Baron of Auppegard and Gourel, grants to his vassal, the Lord of Blancmesnil, the right of administering justice on the farm du Bosc . . . the same farm du Bosc on which poor Mathieu received his thrashing. An amusing coincidence, very amusing indeed: what do you think, young man?"

This time, Simon was pierced to the quick. It was impossible to imagine a more impertinent answer couched in more frank and courteous terms. Quite baldly, under the pretence of telling a genealogical anecdote, Lord Bakefield made it clear that in his eyes young Dubosc was of scarcely greater importance than was the fourteenth-century yeoman in the eyes of the mighty English Baron Bakefield and feudal lord of Blancmesnil. The titles and exploits of Simon Dubosc, world's champion, victor in the Olympic Games, laureate of the French Academy and all-round athlete, did not weigh an ounce in the scale by which a British peer, conscious of his superiority, judges the merits of those who aspire to his daughter's hand. Now the merits of Simon Dubosc were of the kind which are amply rewarded with the favour of an assumed politeness and a cordial handshake.

All this was so evident and the old nobleman's mind, with its pride, its prejudice and its stiff-necked obstinacy, stood so plainly revealed that Simon, who was unwilling to suffer the humiliation of a refusal, replied in a rather impertinent and bantering tone:

"Needless to say, Lord Bakefield, I make no pretension to becoming your son-in-law just like that, all in a moment and without having done something to deserve so immense a privilege. My request refers first of all to the conditions which Simon Dubosc, the yeoman's descendant, would have to fulfil to obtain the hand of a Bakefield. I presume that, as the Bakefields have an ancestor who came over with William the Conqueror, Simon Dubosc, to rehabilitate himself in their eyes, would have to conquer something—such as a kingdom—or, following the Bastard's example, to make a triumphant descent upon England? Is that the way of it?"

"More or less, young man," replied the old peer, slightly disconcerted by this attack.

"Perhaps too," continued Simon, "he ought to perform a few superhuman actions, a few feats of prowess of world-wide importance, affecting the happiness of mankind? William the Conqueror first, Hercules or Don Quixote next? . . . Then, perhaps, one might come to terms?"

"One might, young man."

"And that would be all?"

"Not quite!"

And Lord Bakefield, who had recovered his self-possession, continued, in a genial fashion:

"I cannot undertake that Isabel would remain free for very long. You would have to succeed within a given space of time. Do you consider, M. Dubosc, that I shall be too exacting if I fix this period at two months?"

"You are much too generous, Lord Bakefield," cried Simon. "Three weeks will be ample. Think of it: three weeks to prove myself the equal of William the Conqueror and the rival of Don Quixote! It is longer than I need! I thank you from the bottom of my heart! For the present, Lord Bakefield, good-bye!"

And, turning on his heels, fairly well-satisfied with an interview which, after all, released him from any obligation to the old nobleman, Simon Dubosc returned to the club-house. Isabel's name had hardly been mentioned.

"Well," asked Rolleston, "have you put forward your suit?"

"More or less."

"And what was the reply?"

"Couldn't be better, Edward, couldn't be better! It is not at all impossible that the decent man whom you see over there, knocking a little ball into a little hole, may become the father-in-law of Simon Dubosc. A mere nothing would do the trick: some tremendous stupendous event which would change the face of the earth. That's all."

"Events of that sort are rare, Simon," said Rolleston.

"Then, my dear Rolleston, things must happen as Isabel and I have decided."

"And that is?"

Simon did not reply. He had caught sight of Isabel, who was leaving the club-house.

On seeing him, she stopped short. She stood some twenty paces away, grave and smiling. And in the glance which they exchanged there was all the tenderness, devotion, happiness and certainty that two young people, can promise each other on the threshold of life.

CHAPTER IITHE CROSSING

Next day, at Newhaven, Simon Dubosc learnt that, at about six o'clock on the previous evening, a fishing-smack with a crew of eight hands had foundered in sight of Seaford. The cyclone had been seen from the shore.

"Well, captain," asked Simon, who happened to know the first officer of the boat which was about to cross that day, having met him in Dieppe, "well captain, what do you make of it? More wrecks! Don't you think things are beginning to get alarming?"

"It looks like it, worse luck!" replied the captain. "Fifteen passengers have refused to come on board. They're frightened. Yet, after all, one has to take chances. . . ."

"Chances which keep on recurring, captain, and over the whole of the Channel just now. . . ."

"M. Dubosc, if you take the whole of the Channel, you will probably find several hundred craft afloat at one time. Each of them runs a risk, but you'll admit the risk is small."

"Was the crossing good last night?" asked Simon, thinking of his friend Rolleston.

"Very good, both ways, and so will ours be. The Queen Mary is a fast boat; she does the sixty-four miles in just under two hours. We shall leave and we shall arrive; you may be sure of that, M. Dubosc."

The captain's confidence, while reassuring Simon, did not completely allay the fears which would not even have entered his mind in ordinary times. He selected two cabins separated by a state-room. Then, as he still had twenty-five minutes to wait, he repaired to the harbour station.

There he found people greatly excited. At the booking-office, at the refreshment-bar and in the waiting-room where the latest telegrams were written on a black-board, travellers with anxious faces were hurrying to and fro. Groups collected about persons who were better-informed than the rest and who were talking very loudly and gesticulating. A number of passengers were demanding repayment of the price of their tickets.

"Why, there's Old Sandstone!" said Simon to himself, as he recognized one of his former professors at a table in the refreshment-room.

And, instead of avoiding him, as he commonly did when the worthy man appeared at the corner of some street in Dieppe, he went up to him and took a seat beside him:

"Well, my dear professor, how goes it?"

"What, is that you, Dubosc?"

Beneath a silk hat of an antiquated shape and rusty with age was a round, fat face like a village priest's, a face with enormous cheeks which overlapped a collar of doubtful cleanliness. Something like a bit of black braid did duty as a necktie. The waist-coat and frock-coat were adorned with stains; and the over-coat, of a faded green, had three of its four buttons missing and acknowledged an age even more venerable than that of the hat.