Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

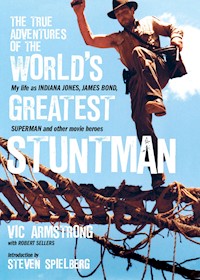

You may not know it, but you've seen Vic Armstrong's work in countless movies. From performing stunts in the James Bond movie You Only Live Twice to directing the actions scenes for recent blockbusters The Green Hornet and Thor, the Academy Award-winning Vic Armstrong has been a legend in the movie industry for over 40 years. Along the way he's been the stunt double for a whole host of iconic heroes, including 007, Superman, and most memorably, Indiana Jones - as Harrison Ford once joked to him, "If you learn to talk I'm in deep trouble." As a stunt co-ordinator and second unit director, Vic is behind the creation of such movies as Total Recall, The Mission, Dune, Rambo III, Terminator 2, Charlie's Angels, Gangs of New York, War of the Worlds, I Am Legend and Mission: Impossible III, to name but a few, as well as several Bond films. He's got a lot of amazing stories to tell, and they're all here in this hugely entertaining movie memoir, which also features exclusive contributions from many of Vic's colleagues and friends, including Harrison Ford, George Lucas, Martin Scorsese, Pierce Brosnan, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Angelina Jolie, Kenneth Branagh and Sir Christopher Lee. With an introduction by Steven Spielberg, and over 100 previously unpublished on-set photos from Vic's own collection.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 674

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

“No CGI can match what Vic can accomplish.”

STEVEN SPIELBERG

“Vic Armstrong is, of course, a legend in the film world.”

MARTIN SCORSESE

“No one does better action sequences than Vic. Some stunt co-ordinators are good with explosion scenes, some are good with car chases or gun battles. But Vic is a master of them all.”

ARNOLD SCHWARZENEGGER

“I’d call Vic a mild-mannered man, like Clark Kent, but under that he’s Superman. It was a pleasure to work with Vic on the Indiana Jones pictures... he really was a great addition to our team.”

GEORGE LUCAS

“Vic has evolved from a stuntman to a filmmaker, and one of the best.”

HARRISON FORD

“He knows what makes a great action sequence, and where to put the camera so you get bigger bangs for your bucks. He’s the man.”

PIERCE BROSNAN

“Be warned, whenever Vic says ‘I’ve got an idea’, something dangerous is about to happen. That’s why we love him.”

ANGELINA JOLIE

“He is one of the greatest ever stuntmen, a top second unit director, a top stunt co-ordinator, and also a director in his own right. He’s had a great career and deserves it.”

SIR CHRISTOPHER LEE

THE TRUEADVENTURESOF THE

WORLD’S

My life as INDIANA JONES, JAMES BOND,

GREATEST

SUPERMAN and other movie heroes

STUNTMAN

VIC ARMSTRONG

with ROBERT SELLERS

Introduction by

STEVEN SPIELBERG

TITAN BOOKS

THE TRUE ADVENTURES OF THE WORLD’S GREATEST STUNTMAN MY LIFE AS INDIANA JONES, JAMES BOND, SUPERMAN AND OTHER MOVIE HEROES

ISBN: NEEDED

Published by

Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd.

144 Southwark St.

London

SE1 0UP

First edition: May, 2011

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

The True Adventures of the World’s Greatest Stuntman: My life as Indiana Jones, James Bond, Superman and other movie heroes copyright © 2011 Vic Armstrong and Robert Sellers. All rights reserved.

Designed by Martin Stiff

Production by Bob Kelly

Did you enjoy this book? We love to hear from our readers. Please e-mail us at: [email protected] or write to Reader Feedback at the above address.

To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive offers online, please sign up for the Titan newsletter on our website: www.titanbooks.com

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Printed and bound in the USA by RR Donnelley

DEDICATION

TO

BOB ARMSTRONG, MY FATHER AND MY FRIEND.

HIS GUIDANCE AND INSPIRATIONAL LESSONS IN LIFE MADE ME WHO I AM TODAY. ANN, MY MOTHER FOR HER LIFELONG SUPPORT. WENDY, MY WIFE FOR HER NEVERENDING LOVE AND PATIENCE. MY BROTHER ANDY AND SISTER DIANA FOR ALWAYS BEING THERE.

BRUCE, NINA, SCOTT, GEORGIE AND ROBERT MY GRANDSON BECAUSE I LOVE THEM.

With Special Contributions By

LORD ATTENBOROUGH

KENNETH BRANAGH

PIERCE BROSNAN

HARRISON FORD

RENNY HARLIN

ANGELINA JOLIE

RAFFAELLA DE LAURENTIIS

SIR CHRISTOPHER LEE

GEORGE LEECH

GEORGE LUCAS

ARNOLD SCHWARZENEGGER

MARTIN SCORSESE

RICHARD TODD

and MICHAEL G. WILSON & BARBARA BROCCOLI

Contents

Introduction By Steven Spielberg

Take One

Starting Gates

Breaking Into Movies

The First Ninja

Stunt Man For Hire

Bond On Ice

Surviving The Recession

David Lean

How To Fall Out Of A Helicopter

Learning From The Best

Historical Epics

The Curse Of The Green Jersey

Back In Bondage

Close Encounters Of The Kubrick Kind

Family Business

Small Screen Stunts

Vic Of Arabia

Face To Face With Oliver Reed And Peter Sellers

Mrs Mick Jagger

A Bridge Too Far

Superman

Winner Takes It All

Dalliances With Disney

High Adventure

Hal And Burt

Leaps Of Faith

A Werewolf In Piccadilly

Raiders Of The Lost Ark

Escape From Baghdad

Never Say Never Again

The Return Of Indy

Fantasy-Land

Up The Amazon With De Niro

The Real Mafia

Steve, Sly And Ken

The Last Crusader

Total Recall

Trouble In Thailand

Future Wars

Director’s Chair

Arnie’s Last Stand

A Touch Of The Errol Flynns

Bug Hunt

Tomorrow Never Dies

A Double Dose Of Connery

The World Is Not Enough

Vic’s Angels

Marty And Harvey

Die Another Day

Cruise Missile

Roy

Last Man Alive

China Syndrome

Superheroes

Looking Back

Filmography

Index Of Names And Film Titles

Steven Spielberg, myself and Harrison on the set of Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom.

INTRODUCTION

By STEVEN SPIELBERG

I have astonishing memories of Vic Armstrong, from the early days of Raiders of the Lost Ark right up to War of the Worlds. What Vic means to me, and to many of my contemporaries, is his capacity to do the impossible. He can make the wildly improbable seem totally credible. He can perform amazing feats, as well as planning them for other people to do safely.

I’ll never forget the scene in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, one of the most reckless things he ever did. The scene involved a fantastic leap from a galloping horse onto a speeding tank. Like so much of his work, that seemed totally outrageous at the time, and yet he did it himself with what I call courage, but he would simply say nerve!

There were many more great moments in his work on my movies. But one of the greatest came when Harrison Ford suffered a bad back injury in a big fight scene in Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom. It put him out of action for three weeks – and the picture would have ground to a halt if Vic hadn’t stepped forward. He stood in for Harrison and saved the picture from a pretty disastrous shut-down.

And of course he’s still at it. He was as cool and indomitable as ever on the very complex War of the Worlds, where the world seemed to be coming to an end with Vic’s help. I remain deeply impressed by his very British cool – a response to any challenge, however difficult or dangerous it might be, that is always casual, easy and amiable. Whatever I ask he sets about it without fuss.

It’s no wonder that Vic was given a lifetime achievement award by his peers. He certainly gets another one from me. No CGI can match what Vic can accomplish.

Take One

For several weeks, five or six times a day, I threw myself onto a manure heap. I guess I should elaborate a little. I was training a horse to run and hold a straight line, while I stood up on his back at a gallop, and leapt off. I was measuring how far I could leap, and also testing the horse’s honesty. I was pretty sure the horse would be reliable, because he was an old friend called Huracán that I had ridden many times before; it was my ability to get the timing right and achieve a constant distance that was the biggest concern.

Cut to two months later and I’m suited up in the famous garb of Indiana Jones, battered jacket, fedora and trusty whip at my side, galloping along looking between Huracán’s ears, judging his speed. I get a sudden flashback to when I was nine years old, perched on the back of Roy, my first racehorse, flying up the gallops at home. I settle Huracán down as we race up a slope to arrive parallel with a rumbling, circa WWI tank. We stay at the same pace as this metal monster, and as close to the edge as possible without slipping into the yawning chasm between us. My heart rate picks up as I start counting the horse’s stride pattern in my head, ‘one, two, three, four...’ judging the amount of strides to the position we’ve agreed is the best spot for the camera to capture the action.

Totally in rhythm, I count the final ‘three, four’ and in time with the horse’s stride I kick my feet out of the regular stirrups, pull my knees up to my chin and crouch momentarily on the stunt stirrups, up by the saddle. On the next beat, which is the ‘up’ stride for Huracán, I straighten my legs from the squat position and kick as hard as I can sideways. Huracán runs straight as an arrow and I’m airborne... but in a split second I realise I’m in big trouble.

I’ve mistimed the jump minutely, not getting all of the impetus I needed, and from being a heroic, dashing figure flying through space, I turn into a Tom & Jerry character, bicycling and clawing my way through the air, trying desperately to clear the gap, the revolving tank tracks and certain injury to land any way I can on the machine. I make it – just. Disaster has been averted. But even as I’m getting my breath back, it’s time to dust myself off, catch my horse and go for take two. Welcome to the world of a stuntman.

STARTING GATES

I always feel a broken bone is a failure, but accidents do happen. Over my years as a stuntman I’ve broken my shin, my arm, my nose and my collarbone, busted my ribs and knackered one heel. The shin was a nasty one. I was in Morocco, and a horse I was riding did a somersault. My stunt friends drove me around Marrakesh to find a hospital and they even had to inject me with morphine. The next thing I knew, I was waking up in a hospital mortuary next to a dead body. The glamorous life of a stuntman, eh?

Movie stunts have been my life for the past 40-plus years, and when I look back on some of the things I did I think I must have been a little crazy, although they were all calculated. I once fell 100 feet off a viaduct for one of the Omen films; I’ve jumped off a 340-foot building on a wire, fallen out of a helicopter onto the side of a mountain, and yes, leapt off a horse onto a moving tank as Indiana Jones.

All the same, it was a sheer accident that I got into the business in the first place, as it is for most stunt people. I originally wanted to be a steeplechase jockey. Since I can remember I’ve loved horses and before I could even walk I was riding them. My parents owned a donkey and as a baby they used to put me in a Victorian basket saddle that’s just like a chair made out of wicker, but with a girth that lets you attach it to the horse or donkey like a saddle. They let the donkey graze in the garden with me on its back. It helped that I grew up in the country, in Farnham Common near Pinewood Studios. I was born at a place called Collingswood nursing home, which is even closer to Pinewood. I guess it was destiny that I ended up working at that famous studio so much.

I inherited this love of horses from my Dad, Robert Armstrong, who was farrier to the British Olympic team from 1948 through five Olympic Games to the Tokyo Olympics in 1964, travelling around the world shoeing Olympic gold medal-winning horses and helping with the training. He was an absolute genius; they say he had a rubber hammer because he could shoe any horse without the animal ever getting fractious. Dad had a great way with horses; like the Horse Whisperer, he could touch any horse and it would be calm with him. He became very famous in his field and knew the Queen; he met her lots of times. Mum and Dad got invites to cocktail parties at Windsor Castle with the Queen and Prince Charles and Princess Anne. Dad was also an honorary member of the British Horse Society and a Fellow of the Worshipful Company of Farriers, an honour bestowed on him by the Lord Mayor of London. People all over the world knew him from his travelling with the British Olympic team. He was even a guest on What’s My Line? once with Eamonn Andrews, and I remember crowding around a tiny television set to watch it.

At the family home, Hawkins Farm in Farnham Royal, Buckinghamshire. My sister Diana is in the cage. I think she locked me out for some peace and quiet.

I still have a memento from those days which was presented to Dad: one of the shoes which Dad had made and nailed on for Foxhunter to wear when he won the Olympic gold medal at the Helsinki games in 1952. It is now chromium plated and mounted on a plaque inscribed ‘To Bob Armstrong, without whom we would not have won the gold medal.’ Foxhunter and his rider Sir Harry Llewellyn were national heroes back then.

I’m about 3 or 4 years old in this photograph.

Dad grew up in the Gorbals in Glasgow, Scotland, in incredibly austere times, and then my Granddad came down south during the 1914-1918 war. He was a farrier sergeant major with the remounts, which were the horses that got wounded during the war and were shipped back to England to get patched up, before being sent back to the Somme. He was based at the stables in Datchet in the grounds of Windsor Castle. Granddad then bought a blacksmith shop on the corner of Slough high street, behind the Crown Hotel, and Dad started working there aged nine years old. His first job was shoeing the pair of Oxen that travelled around advertising OXO cubes, because he was the only person small enough to be able to get underneath the Oxen to shoe them. He worked really hard, and eventually he took over the business.

I remember my Dad telling me a story about shoeing this one particular horse when it kicked out before he’d finished – the nail went in the back of his hand and ripped all the tendons out. He looked at the damage, trying to fish out these pieces of what he thought were filings off the horse’s foot from the back of his hand, but in fact they were bits of tendon sticking out. He finished shoeing the horse, then cycled from Slough with his hand in the air to try and stop the bleeding, all the way to Windsor hospital where they bent his hand right back to shorten the tendons and stitched them all back together. That’s the sort of people they were in those days, tough and hard working.

Dad also used to train with all the top boxers of the day, such as Eric Boon. Dad would run with them in the mornings then go into the blacksmiths and start work while the boxers had a rest. Later in the day the boxers would come into the forge to work with the striking hammer, which is a seven pound hammer, and they would hit the hot iron in rhythm to help them with their punching power.

Mum and Dad were incredible adventurers too and in 1955, when I was nine, they sold all their belongings, uprooted and went to live in Kenya. It was a huge step for a young family; my sister Diana was 11 years old and my brother Andy was just eight months old at the time. A friend of Dad’s owned some riding stables out there and wanted him to be a partner and run them. We sailed out from Southampton and went through the Bay of Biscay where everybody was terribly ill because of the mountainous seas. Then we stopped in Aden and saw the local tribe coming out of the desert. We also went through the Suez Canal, and I’ll never forget waking up and seeing a camel walking by the porthole of the boat as we were going up through it; amazing memories.

We got off the boat at Mombassa and continued our journey by train through the National Park where you’d see elephants, rhinos and giraffes walking around. Unfortunately, when we arrived at our final stop we discovered that the woman who wanted Dad to work with her was actually going through some kind of mental breakdown and didn’t have all the facilities she said she did, it was all pie in the sky. We’d also arrived in the middle of the Mau Mau uprising, terrorists who were trying to drive out the white settlers. Sadly this woman was subsequently murdered. They found her with her arms and legs broken, and think the Mau Mau killed her.

With no work, we lived in the Queen’s Hotel in Nairobi for three months, burning up all our savings. Then salvation arrived in the form of the Jockey Club, who were opening the racetrack in Nairobi and wanted Dad to move up country to a little village called Enjuro, to manage 300 racehorses on this huge spread of land. Dad trained them and we shipped the horses down to Nairobi to race every weekend. The remnants of the British Empire were still largely visible, all the tea plantations were still there and even now when I smell wood smoke I’m instantly taken back to Kenya as a nine year-old, and I can still taste the red dust.

One of our annual family photographs, at Hawkins Farm before we went to Kenya. I have my treasured air gun that Dad brought back from abroad.

It was freezing cold in the mornings and I tried to be like the local kids and walk barefooted, but by ten o’clock you couldn’t walk on the ground it was so hot. I got into trouble with my Mum once when I swapped my new leather sandals for a pair of shoes made from car tires that the local kids used to wear. Another time we came home from the races to be met by my sister Diana, who being the only one at the farm was asked by one of the African riders to help him because a horse had stamped on his foot and mangled the toes. Diana did not have any antiseptic so she put toothpaste on the foot and bandaged it and he went off very satisfied.

I certainly believe that this trip ignited the adventurous spirit in me, plus the fact that throughout my childhood Dad was always travelling and he’d bring us sweets and gifts and photographs from all over the world. I’ve retraced some of his steps. I went to Nice in the South of France and found the old hotel he once stayed at, and where the stables were, and imagined what they were like when he was there with the British Olympic team. So I guess my lifelong love of travelling started as a kid sailing out to Africa, images I can still remember to this day, even though it’s over 50 years ago.

The Mau Mau troubles were still going on and neighbouring farms were being destroyed. Dad’s friends said he ought to get a gun to defend himself. But even though he was a tough man, Dad was a pacifist and said he couldn’t shoot anybody. Besides, all the black people that worked for us had a great love for Dad and Mum, and while everybody got burnt out around us we were left alone. They were very dangerous times but incredibly exciting, and wonderful for a nine year-old to have no school for a year and just live wild and play with horses and the local kids all day long.

My dad returning home from the Helsinki Olympics, having won the gold medal with Foxhunter.

The 1956 Olympics in Sweden were coming up and the British show jumping society called Dad asking him to come back and work for them. It was a big decision to make, should he stay out in Kenya or move everything back to England? We weren’t making a lot of money out in Africa so we came back home and basically started again from scratch, which was a huge undertaking. But Dad would always manage to buy somewhere, we’d renovate it and then sell it and move on; it drove my Mum mad because we were always moving from house to house. We used to live out of tea chests, because in those days all your packing was done in tea chests.

While he was shoeing horses and travelling with the British Olympic team Dad loved his racing, buying and selling horses. Dad travelled to many different yards shoeing, and would see a horse they wanted to sell because it was no good or had a bad leg. Dad was a great veterinary blacksmith, he could cure all sorts of ailments with feet; he made some incredible surgical shoes which I’ve kept as mementoes. So he’d buy these horses very cheaply – we always bought cheap – and correct them with his shoeing, get them better and then race them. He trained all of them himself, getting up an hour early, about four o’clock, before going to work. And he had a few winners, too.

After a while Dad expanded the training side of his business to training other people’s horses, and that’s how we met Richard Todd. In the 1950s Richard Todd was one of the biggest film stars in the world. I took him back to Pinewood Studios in 2001 when I was preparing Die Another Day and the whole place came to a standstill. We went into the restaurant and everybody’s head swivelled round as though the Queen had walked in; we couldn’t eat for people coming over and shaking his hand. And I was telling him about the Bond film and the plans for the car chase in Iceland and he said, ‘Oh, we trained there before the Second World War, doing our arctic training.’ When I was filming there, dressed in all the best clothes modern technology could provide, I imagined Richard there with leather boots and canvas windproofs rehearsing arctic warfare. He was actually the first officer to parachute into Arnhem; an amazing character.

RICHARD TODD

I owned a racing stable and Bob Armstrong was our farrier, he was one of the top farriers in Britain. But he was more than just a farrier, he was also a horse master and a good horseman, he understood horses and had a way with them. And from being our farrier he eventually took over the training. He was a super chap, a splendid man. I was a great respecter of Bob’s unique skills.

Whilst I knew Bob in all those early years in the ‘50s and ‘60s Vic was around with his sister Diana, they were just a couple of kids, and both were horse experts, like their father. I’ve heard that because I was filming and I always did my own stunts, I never allowed anybody to do a stunt for me, Vic was determined to be a stuntman himself eventually, and it gave him his interest in filming and stunt work. And I watched his career grow to him becoming the leading stuntman in this country.

Richard Todd turned out to be a great patron of Dad’s and kept us going for years and years bringing over his horses for us to train. And that’s when I started dreaming of the movies. Richard Todd would tell us of the films he’d worked on, Robin Hood, Rob Roy, and then I’d go and see them. As a kid I used to play cowboys and Indians and throw myself off my ponies, which drove my Dad mad. ‘Never throw yourself off a horse,’ he’d say. He was a bit like a pilot watching parachutists jumping out of a perfectly good plane. They just could not see the logic in it. I used to go to the movies and recreate what I saw back at home. I rode Richard Todd’s horses in all their races as an amateur after that, which was wonderful.

The Village boys’ football team in Marsh Gibbon, Bucks. That’s me, bottom left.

I was always a dreamer, always fantasising and playing games and that’s helped me as a stunt co-ordinator. That’s all you do when you co-ordinate something, a fight or an action sequence, you fantasise, you play cowboys and Indians, except somebody gives you a few million pounds to do it with, and all the toys and the equipment you need.

Because Dad was always moving around, I ended up going to 23 different schools. I’ll never forget we had a horrible maths teacher at this one school. I hated this guy, he was a horrible bastard, and I was bottom of the class; 34 of us and I was bottom. When he left, a new teacher came in that I also did technical drawing with, and I did very well in technical drawing, and the next term I came top in maths. But when this teacher left, the nasty bastard came back and I dropped to 34th again. But that was a great lesson, it proved to me that I wasn’t an idiot, that if I put my mind to whatever I wanted to do, I could reach the top.

In those days I just wasn’t interested though, because I knew exactly what I wanted to do for a living: I was going to be a steeplechase jockey and that was it. I didn’t figure I needed higher education. I think all the travelling I did gave me more of an education than I could ever have got from school anyway. I was a great reader, too. I used to devour the National Geographic magazine and books. That was my film training, reading books. I loved visualising what was going on. I had a great imagination and used to write these fantastic stories for my English lessons, which is what I do now, but put them on film.

My life totally revolved around horses. I’d get up at six o’clock to help out at the stables and then cycle to school absolutely pumped up. The other kids coming in had just got out of bed. I felt so much older and so much more advanced than they did. I’d come home for dinner and then it was back to the stables. Weekends were even busier because the jockeys all came down for training sessions with the horses; it was all hands on deck. All this taught me great responsibility. My school mates would go off on weekend trips but I couldn’t because I had horses, I had responsibilities, the horses had a training schedule, somebody had to feed them, we couldn’t afford anybody else to do it, I would do it.

Working with horses also instilled in me great discipline. I’ve always been a real disciplinarian and a believer in mind over matter. Even as a kid I was a big lad. When I left school I was six foot plus and used to starve myself to death to get down from 14 stone (210lbs) to ten stone (140lbs) just to ride racehorses (with riding the height doesn’t matter, it’s just what you weigh), that’s getting on for a third of your body weight, but I did it. You force yourself to do these things. It builds character. You force yourself to do things you’re frightened of, heights and falls and stunts. It’s mind over matter. I think that’s what I learnt from working with horses and racing. And it’s bred in me, it’s in the family; Dad would never give in, he’d always keep going and going. He’d never take time off for illness; the only reason you don’t turn up for work is because you’re dead. That’s why I’m a bit hard on my film crews if somebody doesn’t turn up because they’ve got a runny nose, it’s because I come from a different world to them, totally different principles and values.

I was just nine when I rode my first racehorse. At the time we had a little semidetached house that backed onto the gallops and Mum stood at the end of the garden to watch me. It was on a horse called Roy and I sat perched up on his neck staring straight ahead between his ears and just went for it, it was an amazing feeling. After that Roy became my horse to look after, and in the summer holidays we’d go down to the West Country, to Exeter and Newton Abbot in Devon, for race meetings. In the evenings it was a trip to the movies and then a fish and chips supper before going back to sleep in the straw in the horsebox, we couldn’t afford a hotel. Then we were up at five working the horses. I used to lead Roy round in the parade ring at the racetrack before the jockey got on, and felt so proud and grown up.

At our stables in Sussex. Andy is riding our donkey Harold Wishbone, and Dad is shoeing Fixture, a horse I later rode in races. I’m about 13 here.

Then at 11 years old an accident almost scuppered any hopes I had of being a jockey. I was out riding a lovely but lively racehorse of Dad’s called Bell of Andrum when a pig ran up to a fence and the horse reared up. It was my fault, I hung onto its head and pulled him over backwards and he fell on top of me, bashed me up pretty bad and that scared me from riding racehorses for over a year. Then when I was 12 Dad sold the horse that fell on me, and which so terrified me, to a local guy called Jeff Robinson, who used to help out at our stables when he was a teenager. And that really fired me up to get back into riding. I thought, my God, if he can ride that horse so can I, because I always figured I was streets ahead of Jeff as a rider. And I never looked back after that. I’d ride horses from before dawn till after dusk, not bothering to go to school. The school inspector would visit my Mum at home saying, ‘Where is he? He hasn’t been at school.’ And Mum would say, ‘Oh he’s got a terrible cold. He’s in bed.’ Then I’d actually go galloping past the guy in a pack of other riders and he’d think I was a man; I was growing up so fast.

Just before the 1960 Rome Olympics I went with Dad and the British team to Dublin; it was their last big show jumping event before they went off to do the Olympics. During our visit the Ballsbridge sales were on, so Dad and I went to have a look. While we were there a horse came up for sale that went on to become one of the most famous racehorses in history: Arkle.

Right before Arkle in the sale ring was a little broken down horse called Trebor that Dad fancied, but he was beaten in the auction by his good friend Fred Broome, the father of David Broome, the famous show jumper. The Broomes raced Trebor but both of his front legs broke down, the tendons just went, and Dad was able to buy him for £100 (along with a donkey we called Harold Wishbone which my brother Andy learnt to ride on). We kept Trebor all through that winter, starved him down, got him skinny, which lightens the load on the damaged tendons and thins the blood down, and I then hunted with him, which got him really strong and fit.

On 20 March 1960 we went to the Hursley Hunt races at Pit Manor near Winchester; I rode him in the members’ race and we just ran away with the race and won. And I won that same race three years running. I was 14 and I’d already ridden my first winner, it was so exhilarating. That’s when I decided to leave school, I just didn’t go back. After that race there was nothing else in my mind, I wanted to race horses for the rest of my life.

Trebor, which ironically is my Dad’s name spelt backwards, was one of the greatest horses I have ever sat on, and it broke my heart when one day after we had finished a race at Exeter he died of a heart attack as I was walking back to the weighing room. It was so typical of his courage to have finished the race when he obviously was not well.

I was coached in race riding by Michael Haines, who was our stable jockey and one of the classiest riders I have ever seen on a racehorse to this day. I think Mick was as excited as I was when I won that first race. I would have loved to have been a professional jockey, but my six foot, one inch frame was against me, so I stayed an amateur.

Soon I was riding regularly in races and it was great because Dad and I worked as a team. I was the rider and he was the guy on the ground and there wasn’t a horse that we couldn’t work between us, wild young horses, crazy horses that we’d get cheap because they were a handful or had some problem, but we’d train them and race them, because that’s all we could afford. I continued to race even when I became a stuntman. My movie pay basically funded our racing. We were a very democratic family – what I have, everybody else has. When I first started driving a car (legally) and wanted to go out one night, the whole family had a whip round to buy a gallon of petrol. And I’ll never forget when I first got the opportunity to join the Actor’s union Equity and I didn’t have enough money to pay the £22 fee, a huge amount in those days, my sister Diana, who had a job at Liberty’s store in London, lent me the money. So I grew up with a great respect for money because I knew how hard it was to get and to keep. What money we had was usually spent on the horses. Whenever we bought a new house the first thing that was renovated was the stables.

Unless you’ve lived and grown up around horses it’s difficult to relate to that way of life because you don’t actually make any money out of horses. You might sell a horse for more than you paid for it, but it has cost you a bloody fortune to run up until then. You do it for the sheer love of horses. When it gets in your blood, it just consumes your whole life. And you’ve got to have that passion. I love movies, but horses are my real passion. Any stunt I’ve done and been proud of doesn’t compare with the sensation of galloping into a steeplechase fence with 20 other horses and jockeys thundering along beside you in the environment of a race. It’s incredible the rush you get, and the sense of achievement, whether you win or lose, is fantastic.

It’s also the association of man and animal, it’s working together as a team, it’s the danger, it’s the noise, it’s the whole essence of it, and the competitiveness, just the mixture of everything. Horse racing is like the film business, it’s a small community and you’re all competitive but you all have respect for each other, even though you also think you’re better than each other. I couldn’t bear to sell any of my racing saddles, each one has a memory, and they’re so dry they’ll probably snap if you use them now, but they all have incredible memories. Horses have got me where I am today. I’ve got nice cars, beautiful homes, all through being able to ride a horse, which isn’t bad.

I carried on racing right through into the 1970s in between my film work, and Dad and I would still wheel and deal together, sell and buy horses. One day when I was working on Superman I could not lose the usual amount of weight I would have to in order to ride one of our horses in an upcoming race, because of my commitment as Chris Reeve’s stunt double. I said to Dad that we needed to find a good amateur jockey to ride this particular horse and Dad turned to me and said, ‘For two pins I’d love to ride it myself.’ And suddenly the penny dropped – all through those austere years as a blacksmith and training his own horses, he’d have given anything to ride them in a race himself.

Here I am racing at Horseheath in Cambridgeshire.

He was always a great horseman and taught me so much, such as the gift of having light hands, which would control an unruly horse far better than heavy hands. And when I came into the business as a jockey he was always generous in his encouragement and pride towards me and loved me riding his horses, but deep down he really wanted to do that himself and had never mentioned it once, until that moment when I could tell from his voice that he’d always dreamt of racing. ‘Well,’ I said, ‘why don’t you go for it, Dad?’ And he went, ‘I think I will.’ He was 69 years old. He had to go to Weatherbys, the governing body, the licensing people for the jockeys, to have a medical, which he passed with flying colours. In fact the doctor said, ‘Good heavens, I wish I was as fit as you and I’m 20 years younger.’

Dad’s first race was at Lingfield in Surrey and it made headlines in The Sporting Life newspaper because the cumulative age of the horse, jockey and trainer was 124. Because it was a flat race, which needs a special licence, we had the horse in training with a wonderful old lady called Norah Wilmot; she trained horses for the Queen and the Queen Mother and was one of the first women to be granted a trainer’s licence by the Jockey Club. And then he rode up at Redcar and was never less than as cool as a cucumber; he wasn’t flustered or nervous at all. My heart was thumping like mad!

Dad never retired, he kept on going. He had great strength of character. I saw times when it was rough, not much money and bills to pay, but Dad never worried too much. He’d worry about it inwardly but never worried the rest of the family about it, and we’d always get through it, and we did pretty well in the end. And Mum was always there and supported Dad. She was real salt of the earth, a hardworking woman. Not really a horsy person, she’d had a couple of riding accidents that put her off a little bit. She’d been in the land army during the war and drove a lot. She taught me to drive when I was six years old.

Both Mum and Dad were always very proud of my racing. I think it was the proudest day of Dad’s life when I won my first race. And he was tremendously proud of my stunt career. He came out on a couple of movies, he knew the film business pretty well and was proud of what I was doing in it. He didn’t like the idea of me falling off horses though. When I broke my leg in Morocco on a film he was a bit worried about that, as I would be. I often think about it now, with kids of my own; I would worry to death if that had happened to them, but both my parents had total trust and faith in my decisions, and that was wonderful.

Dad was the biggest inspiration on my life. His entrepreneurship, the bravery of him going out and trying new things, experimenting with life, his knowledge and the respect people had for him, all of that came together to give me confidence to go and be a stunt co-ordinator and a second unit director. My father reached the top of his profession and that really drove me to want to be the best. When I started in the business I wanted to be the best stuntman in England. And that kind of drive came from Dad. He was the most amazing guy I’ve ever met and also my best friend.

BREAKING INTO MOVIES

Even in the crazy world of show business, the leap from steeplechase jockey to movie stuntman is a considerable one. But I’d long fancied the chance to get into films, especially when I heard about the sort of money you could earn, between ten and 15 pounds a day, which was phenomenal. I was earning two pounds a week if I was lucky as a jockey. So it all sounded great.

Back in the ’60s Johnny Rock was the country’s biggest horse supplier to the film industry, and I was always in and out of his stable yard because Dad used to buy and sell horses from him. One day Rock hired me to drive some horses up to Elstree studios, and that was the first set I remember going on. It was an episode of The Avengers (called ‘Silent Dust’, I think). They were shooting a hunting sequence and these stunt guys had to do a fight rolling under the horses that I’d brought over. I watched and was fairly disgusted. ‘Is that horse safe?’ they whined. ‘Is he going to kick me?’ I thought, who are these wallies? I can do that ten times better. And that’s probably what spurred me on.

Later I heard that Johnny Rock’s stables were being used to audition stuntmen for the Charlton Heston epic Khartoum, so I trawled over, more out of hope than expectation. And so it proved. No one was going to hire a raw rookie on so prestigious a production. But it really frustrated me that most of the guys going were just regular stuntmen and not riders. Then the lucky break arrived courtesy of a family friend, Jimmy Lodge.

Jimmy was the best riding stuntman around, and was hard at work on a spy film called Arabesque with a bunch of horses, hired from the ‘top’ horse supplier at the time, that as far as I was concerned were straight out of Southall market; useless old dogs. They were supposed to jump gates and hedges while being chased through fields by helicopters and Land Rovers with people firing machine guns at them and these things couldn’t even jump over their own shadow. In fact Pam de Boulay, the stuntwoman doubling Sophia Loren, broke her knee when her horse refused to jump a two-foot fence and slammed her into the gatepost. So Jimmy phoned me up in absolute desperation asking to borrow one of our horses, to which I agreed, and then called again saying he had a job for me as a rider doubling one of the leads. I went down there and started riding and that was it, I’d landed my first film, at £20 a day, fantastic. I met Gregory Peck and Sophia Loren, who were icons in those days.

Just starting out on my journey as a stuntman.

As well as stunt doubling, one of my jobs was to hold the horse while the stars did their close-ups. Peck was in the saddle with Sophia holding on behind. Crouching down out of camera range I led the horse in, but it started bucking because Sophia was basically sitting bareback behind the saddle on its kidneys. Pulling up, Sophia looked at me. ‘Veek, Veek, why is the horse bucking?’ And without thinking I replied, ‘Sophia, if you were riding me bareback I’d be bucking, too!’ Oh no, what have I said? Luckily she burst out laughing. ‘Naughty, naughty, naughty.’ I just said it out of the blue. I couldn’t stop myself. But she was absolutely gorgeous Sophia, just breathtaking.

After that experience I thought, this is the life for me, I can work on movies and in between jobs carry on racing and one would finance the other. So I looked for advice from people I knew in the film business, but they all shut the door, nobody wanted me in it. It’s a notoriously tough business to break into and that hasn’t changed in 40 years. Thank God Jimmy Lodge gave me my start.

So I went up to London thinking, the only way I’m going to get on in this game is to have an agent. In the mid-’60s there was only one stunt agency, HEP, originally formed by Frank Howard, Rupert Evans and Joe Powell. Tragically Frank Howard was killed on a movie in Morocco when a horse rolled over him, so his wife Gabby ended up running the agency and I became the youngest stuntman on their books. My greatest asset then was my youth. I was the young kid on the block. You’d go to auditions and line up against a wall with all these old stunt guys and the actor would walk in and see me and say to the director, ‘Oh, I think the young man on the left is the best double for me.’ You might not look anything like them but their egos kick in. So I got a lot of work very quickly.

Back in the ’50s the majority of stuntmen came from a military background, they’d been commandos and the like in the war, and weren’t really classified as stuntmen, just glorified extras who did the odd bit of riding and stunt work. Then people like Joe and Eddie Powell, George Leech, Bob Simmons, Jock Easton, Ken Buckle, Alf Joint, Paddy Ryan and others built up reputations and started getting paid extra for stunt work, but still a pittance compared to America, where it had begun much earlier and in a much bigger way. Cut to the ’60s, and nobody new was coming in apart from the odd mini cab driver, ex-boxer and doorman drafted in to play a heavy and be in a fight, so they became stuntmen. But that’s all it was in those days. So when I arrived in 1965 there was nobody else in the stunt business except this old brigade. I was really one of the first of a whole new generation, along with people like Rocky Taylor, Martin Grace, Bill Weston and Marc Boyle.

Pretty soon I’d set myself the target of becoming the top stuntman at the HEP agency. Gabby was terrific with me, getting auditions, introducing me to the right people, and jobs quickly came along. I’ll never forget one of them. It was for a TV show and I had to double this guy vaulting over a 12-foot chain link fence. The director yelled ‘Action’ and I ran, took one jump, hit the fence halfway, bounced over the top and was gone (like a early version of Parkour). The director was astonished that somebody could fly over a fence as easy as that, so didn’t need another take, and wrapped. In those days you were paid on the day in cash and I got seven pounds, ten shillings. ‘I thought I was on £15 for the day,’ I said. ‘Yes, but we finished by lunch time so we only have to give you half.’ I phoned Gabby, who was livid. ‘They contracted you for a day and you should get all the money.’ She eventually managed to get my other seven pounds, ten shillings out of the company. Great lady, Gabby; she was very sweet and whenever I was in her office hustling for work she would always reminisce and tell me how much I reminded her of her Frank.

Other small jobs followed until, early in 1966, I was sent along for an audition at the old MGM studios in Borehamwood. It was for a First World War picture called The Bells of Hell Go Ting-a-Ling-a-Ling, again starring Gregory Peck and financed by the Mirisch Corporation, who were behind such hits as The Magnificent Seven and The Pink Panther. I was to double for Ian McKellen (now Sir Ian of course) in his screen debut. ‘You’re perfect,’ they said. ‘But we’re waiting to see one more stuntman.’ I came back an hour later and he still hadn’t showed; another hour, still no show. Third hour there was a heavy bang on the door and this guy walked in, who has been a lifelong friend ever since, and godfather to my eldest son Bruce, Bill Weston. He had long hair and a scruffy beard and looked like the wild man of Borneo, and here we were supposed to be doubling clean-cut young pilots. ‘I’m terribly sorry I’m late,’ he boomed. ‘Just got in from the Bahamas, been crewing a yacht out there.’ The producers stared with incredulity at him, trying to visualise what he looked like without half a haystack of hair. Old Bill said, ‘If you give me the job I’m willing to shave it off.’ And he held up a razor in one hand and a shaving stick in the other. ‘We’ll let you know,’ said the producers.

Outside Bill introduced himself and cadged a lift back to Slough train station. ‘I think you’ve got the job,’ he suddenly announced. I wasn’t so certain, this being my first big audition. ‘I can’t do it anyway,’ he went on. ‘I’m up for this thing called 2001: A Space Odyssey.’ Arriving home the phone rang and I was told the job was mine. Bill was right. Even better, it was ten weeks in Switzerland at £75 a week. I was really excited.

The Bells of Hell Go Ting-a-Ling-a-Ling was about an Allied mission to carry aeroplanes which had been dismantled in parts small enough to fit into horse-drawn hay carts through German occupied territory, where they would be reassembled in order to bomb enemy targets, namely the Zeppelin bases in Friedrichshafen. Believe it or not it was all based on a true story. And the budget matched its epic scope. I flew out to Switzerland on an old charter plane from Gatwick, propeller job. I had no money at all and had to borrow a pound off my Dad to buy the duty free cigarettes. I didn’t know anybody either and was totally green about the movie business, but a guy named Eddie Powell quickly took me under his wing. Eddie was famous as Christopher Lee’s stunt double on the Hammer horror pictures and was also Peck’s regular double. He was a lovely man.

When the picture started it was quickly apparent that it was doomed from the outset. It rained, it snowed and the weather forecasts were horrendous; everything went wrong. One day we drove these vintage trucks up a mountain to wait for a camera helicopter to do some aerial shots of us, but by dusk it hadn’t arrived and as we drove back down into the valley the assistant director John Peverall met us. ‘It’s a wrap guys,’ he said. ‘We know it’s a wrap,’ we answered back. ‘We can hardly see our hands in front of our faces.’ He said, ‘No, they’ve cancelled the whole movie.’ The Mirisch brothers had come out to see what was going on. We only had a minute of footage to show them for almost seven weeks’ work and as they sat watching it the projector broke down, so they said, ‘That’s it, pull the plug.’ The next day everyone was flying back to London. The film never got finished. Nevertheless, it was an important film for me because not only was it my first location, I also met many people that would be influential on my career, people like Paul Ibbetson who was the 3rd assistant director, Basil Appleby the production manager and many more that employed me over the years. It certainly made me aware of the importance of networking.

THE FIRST NINJA

Back in London I phoned Bill Weston to tell him how the Swiss job went. His reply was typical Bill. ‘I’ve got a contract here which you can have. I can’t do it.’ He was doubling Keir Dullea on 2001 and it was going on forever, while meanwhile this movie at Pinewood was underway called You Only Live Twice. ‘All you do is just go up there and tell them you’re replacing me.’ I couldn’t believe it. ‘Fantastic Bill. Thanks a million.’

I tore up to Pinewood and was directed to the back lot, where the famous 007 stage stands today. Back then it was just barren ground, out of which had temporarily sprouted a mass of scaffolding so high it could be seen from the main London-Oxford road some three miles away. Within the construction was a masterpiece of set design, a volcano rocket base; the new headquarters of Blofeld and SPECTRE, where the explosive climax to the new James Bond epic was to take place. I was gobsmacked. Inside it was like the Albert Hall. I haven’t seen a set to this day as big as that one. It had its own monorail, a helicopter could fly in and out and the roof slid back. It was phenomenal. My jaw hit the floor. I met legendary action co-ordinator Bob Simmons, who was hiring people to be the ninjas who attack this base. Pointing up to the roof he said, ‘We want somebody to slide down there on a rope firing a gun, think you can do that?’ I said, ‘Piece of cake.’ Bob smiled. ‘All right, you’ve got the job.’ I thought, this is going to be fantastic.

Virtually every stuntman in England had been brought in for this battle sequence, and others besides. There were mini cab drivers, strong-arm men, drug dealers, spivs, everyone you could think of – real tearaways, but fantastic characters. They brought in girls by pretending they were holding auditions for the next Bond movie and filmed them doing the most outrageous things. And they got away with it! You’d be locked up and they’d throw away the key these days.

The first thing everyone had to learn was how to slide down 125 feet from the roof ninja-style, land safely, un-sling their guns and start firing. Bob Simmons came up with this great idea of using a piece of rubber hose that we could squeeze on the rope like a brake shoe to slow the fall. To reduce the friction and try and keep the rubber cool, I used to put talcum powder inside the pipe, but you went really fast at the beginning of the drop until the talc burnt off! Because I was still racing horses my power to weight ratio was tremendous, so I used to roar down and stop at the last minute. But some of these guys were overweight or not strong enough. On one take this guy came hurtling down, whoosh, and straight into the ground. The director yelled, ‘Cut, cut!’ The gunfire stopped, the dead people got up and went back to their starting positions, all except this one guy who was still moaning, ‘Arghhh.’ I thought, he’s a good actor. We walked over and he’d broken both ankles. The poor fellow was in agony.

Handling the descent was easy for me; it was getting up there in the first place that caused the biggest problem. I didn’t like heights in those days and to reach the top of the set you had to climb ladders and scaffolding, which took you ten minutes. Once you were up there it was scary as hell, scrambling along girders, bent over and just three feet below the roof, to get to your drop position, holding onto the rope, just your toes on the girder, with 125 feet of space below you and your arse just hanging out over nothing. Plus you weren’t attached to any safety lines climbing out there or when you came down. When you finally got to your position, if you let go of the rope or slipped, you were a goner.

With the master shots completed Bob Simmons selected 20 of the best stuntmen to handle the more difficult task of zooming down one-handed whilst firing a machine gun. I was amongst the team. Whereas before it was pure strength that held you onto the rope, this time we were attached by a metal device that when pulled on the rope sliding through your hand it slowed your fall. One of the stunt guys, an ex-paratrooper called Tex Fuller, was asked to demonstrate this gadget, which was called a descendeur, at his parachute regiment’s annual reunion in a village hall. He was on a beam ready to slide down when this thing snapped from metal fatigue and he fell ten foot onto the deck. ‘Oh my God,’ he said. ‘I was 125 foot up this morning doing this.’ We all were!

It was discovered these aluminium devices were dangerous because they’d get invisible fractures in them, so ultimately they were junked. The next day at work while we were all discussing the prospect of having to go up onto the girders again with these now suspect devices, one of the stunt guys said that he had heard of these new devices called figure eights. So being the youngest I was sent off to Thomas Black’s, the climbing shop in Gray’s Inn Road in London, to try and find some of these new tools. I bought all the figure eights that they had in the shop and came back to Pinewood triumphantly. The figure eights were thin pieces of metal in the shape of an eight that were much safer than the old descendeur, but bear little resemblance to the thick alloy figure eights that are around today. Ours were so thin that when they got hot sliding down, they would burn through the rope if you did not disconnect them immediately.

As one of the ninjas in You Only Live Twice. That’s me coming down first.

Joe Powell, another legendary stuntman, was our team leader and he took responsibility for tying our ropes onto the girders. He had a wicked sense of humour and you could hear him muttering under his breath – deliberately loud enough for you to hear – as he tied the knot, ‘Is it left over right, or back again, or under there? Oh, that will be all right I think!’ And all this while you are hanging onto a cold and slippery girder 125 feet in the air, about to entrust your life to that knot when you launched yourself off.

By far my biggest job in movies to date, You Only Live Twice