Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Peepal Tree Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

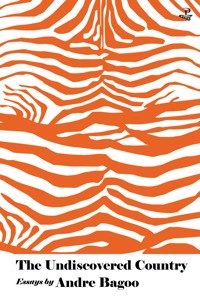

'A manifesto, a literary criticism, a personal chronicle of literary life, a book of days, a stage wherein famous writers such as Walcott, Thomas, Gunn, Espada, and others become actors, The Undiscovered Country discovers many things, but one thing for sure: Andre Bagoo is a fearless, brilliant mind. He can take us from the formal critical perspective to new futurist "visual essay", to verse essay, to sweeping historical account that is unafraid to go as far in time as Columbus and as urgently-of-our moment as Brexit—all of it with precision and attentiveness to detail that is as brilliant as it is startling. Bravo.' — Ilya Kaminsky, author of Deaf Republic and Dancing in Odessa Andre Bagoo is the real deal as an essayist in that he asks interesting questions (was there an alternative to the independence that Trinidad sought and gained in 1962?) and is open to seeing where his ideas take him – quite often to unexpected places. He displays an intense interest in the world around him – including literature, art, film, food, politics, even Snakes and Ladders – but is just as keen to share with the reader some sense of how his point of view has been constructed. He writes as a gay man who grew up in a country that still has colonial laws against gay sexuality, as a man whose ethnic heritage was both African and Indian in a country whose politics have been stymied by its ethnic divisions. And just what were the effects of repeat-watching a defective video of The Sound of Music, truncated at a crucial moment? There is an engaging personality present here, a sharp and enquiring mind, and ample evidence that he knows how to write shapely sentences and construct well-formed essays. Encyclopaedic knowledge is rarely the point of the essay, but few readers will leave this collection without feeling better informed and more curious about their worlds.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 354

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ANDRE BAGOO

THEUNDISCOVEREDCOUNTRY

ESSAYS

First published in Great Britain in 2020Peepal Tree Press Ltd17 King’s AvenueLeeds LS6 1QSEngland

© 2020 Andre Bagoo

ISBN 9781845234638 (Print)

ISBN 9781845235130 (Epub)

ISBN 9781845235147 (Mobi)

All rights reservedNo part of this publication may bereproduced or transmitted in any formwithout permission

CONTENTS

Introduction

The Last Page

Naipaul’s Nightmare

On Henry James

Mark Twain’s Corn-pone Opinions

Doubles

In Plato’s Cave

Romantics in Port of Spain

Soca

Snakes and Ladders

Dylan Thomas: Three Encounters

Ishion Hutchinson

The Show Must Go On

Thom Gunn’s Carnival

Langston Hughes in Trinidad

In The Fires of Hope and Prayer

His Father’s Disciple

You Can See Venezuela from Trinidad

The Rightest Place

An Essay into the Visual Poetry of S.J. Fowler

The Secret Life of a Dyslexic Critic

What Happened on December 21, 2019

Boris Johnson in the Eyes of a Poet

The Free Colony:

I. From Columbus to Brexit

II. The Laws of the Free Colony

III. The Price of Independence

The Agony and Ecstasy of Eric Williams

Michael Jean Cazabon

Bruegel

Crusoe’s Island

Notes

Acknowledgements

The world is an idea.

– Arthur Schopenhauer

INTRODUCTION

In answer to a complex question, Baudelaire has a simple answer. What is art? he asks. His response? Prostitution. This might seem a provocation until we appreciate how both involve the human body, the exchange of money, the mobilisation of market forces, the gaze of an onlooker, the commissioning of illicit acts, the subversion of ordinary relations, the showing up of forms of power, the disavowal of authority, the rejection of absolutes, the expression of needs, the satisfaction of wants. At least for Baudelaire art was in good company; he linked prostitution to love.

This book of essays is concerned with art and politics. Art, whether prostitution or not, is the necessary precursor to politics.

Art encourages us to look, to reflect, and, in the process, to re-imagine. It provokes opinions. It encourages people to speak up, to add their voices to a discourse that, over time, flows like a river, eroding the banks of ignorance. It transports and spreads ideas, sorting and refining the sediment of controversy, nourishing the floodplain of society.

Art is the diversity of the body politic made manifest. It is the granting of visibility to the hitherto invisible. Art shows us people and perspectives we might never otherwise encounter or understand. As Habermas argues, democracy cannot thrive if citizens cannot speak.

Politics is an art. At times it is built on honest ideas, at other times deceptions. Always, it is about style and the exercise of power. It is a fictional narrative, the arc of history, a long epic written and re-written by bards of varying skill.

These essays have been written in the spirit of such ideas. They do not set out merely to report. They castigate and praise. They aim to provoke, to add fuel to the fire of argumentation, the ceaseless discourse on the shape of a place. They make public the private through the trick vessel of art.

In 15th century Europe, “to essay” was to test the quality of something. The Old French word essai meant trial. A critic of literature or the visual arts is a political animal, someone with a point of view who, implicitly or not, argues for a version of the world.

Little wonder the essay has certain attractions for poets. “Both poetry and the essay come from the same impulse,” Marianne Boruch says, “to think about something and at the same time, see it closely, carefully, and enact it.”

The essay, like the poem, has a variety of costumes. It is deeply forgiving: capable of accommodating the polemical, the comic, the visual, the poetic. The Chinese, after the fall of the Han dynasty, created essays that alloyed prose and verse. In this vein, ideas about society flow naturally from the belief that art, art criticism and politics go hand in hand. I am just as interested in observing the world as reading the text – particularly when the one throws light on the other. This book discusses food, film, music and other forms of culture that infuse literature. Though Trinidad looms large, another republic is in view.

While some speak of the rebirth of the essay, the truth is that it has never been out of style. Even today, when people say print is passé, the novel dead, poetry irrelevant, and theatre arcane, essays come to us in an unending stream of newspaper columns, social media posts, diatribes by trolls, comments on online forums, blogs, vlogs, podcasts and websites dedicated to ideas.

Perhaps the essay has never been out of style because it has always been about one thing: its writer. Essays on literature, art, material culture and on politics can be a form of self-care, an affirmation of the value of all perspectives whether we agree or not. When she wrote about Kafka, Margaret Atwood acknowledged that “My real subject was not the author of the books but the author of the essay, me.” Here, then, is a history of myself told in many voices, ranging across genres and nations. Here, to repurpose a Shakespearean phrase, is the undiscovered country.

THE LAST PAGE

Some say time has run its course and that the life we lead is no more than the fading reflection of an event beyond recall. W.G. Sebald observed that we simply do not know how many of its possible mutations the world may have already gone through, or how much time, assuming that it exists, remains.

I like to think about this when I consider V.S. Naipaul and Derek Walcott. Imagine a reality in which neither man became world-famous, in which both stayed in the Caribbean, never leaving to write, travel or live elsewhere. See them holding down office jobs, Walcott plodding along as an arts reporter for a newspaper, Naipaul working as a copy writer, or maybe even a civil servant in the Red House. In this world, neither becomes a Nobel laureate for literature. Nor do they end up mortal enemies. Walcott does not write that poem comparing Naipaul to a mongoose. Naipaul does not write that essay dismissing Walcott as being lost in an imitative swamp. In this world, they meet and become good friends. Their shared passion is writing: a hobby they view from afar. They spend their days in the drudgery of office work, and spend their nights drinking, smoking, talking about Nietzsche, Sartre, Heidegger or whichever philosopher is fashionable at the time.

Whenever I read Miguel Street, this fantasy of mine comes to mind. There is a specific moment in Naipaul’s book, a brief, slight moment, a mere sliver of time, in which a character says something so profound it could well be the key to unravelling all these different worlds.

“Look, boys, it ever strike you that the world not real at all?” the selftaught teacher Titus Hoyte says. “It ever strike you that we have the only mind in the world and you just thinking up everything else? Like me here, having the only mind in the world, and thinking up you people here, thinking up the war and all the houses and the ships and them in the harbour. That ever cross your mind?”

In Naipaul’s hands we are meant to laugh at Hoyte. The fact that he is self-made is not admirable. Rather, it is a kind of hubris, meant to underline his status as an outsider, a person who dares to take custody of ideas and notions meant for others. In some countries, Hoyte might be described as an autodidact. But in Trinidad he is not that far off from a madman. True, he is bad at what he does, but the fact that he is not in a position of power or privilege and has limited opportunities is discounted. The mockery is intensified when we consider how Miguel Street was originally published for the British market, a market that would view the world it describes as a remote, exotic place filled with “characters”. Hoyte’s industry becomes pretentious. He is a black man from a small island who does not know his place and is therefore to be laughed at.

But even a stopped clock is right twice a day. What is fiction if not an exercise in the power of ideas to conjure worlds? One human mind building a world and sharing that world through language? As Derrida might ask, what is language if not a medium by which the world is engendered? What is poetry if not an event in the world that also shapes the world? Titus Hoyte might be crazy, but his questions are not.

There’s a Walcott poem, too, that sends me down the rabbit hole of imagined worlds and alternative realities. It’s the untitled poem that closes his last collection, White Egrets. It begins:

This page is a cloud between whose fraying edgesa headland with mountains appears brokenlythen is hidden again until what emergesfrom the now cloudless blue is the grooved sea

Just as Schopenhauer asks us to imagine the world being generated by an idea, Walcott asks us to commit to thoughts becoming solid in our hands. We look at the page, consider the poem’s block of text. We are given a bird’s eye view of a landscape, inhabiting the perspective of the titular white egrets of the book. The terrain unfurls: the colours of the land, the shapes of valleys, the curves of roads, the serenity of fishing villages. This is not just a picturesque tour. These details allude to the great concerns of Walcott’s oeuvre without explicitly stating them: history, nature, love. Each item is a symbol, pointing to myth as well as social context. The fishing villages are the setting for ancient odysseys as well as the industrial-colonial processes that shaped the Caribbean’s history.

And here what is at first beautiful becomes dangerous. There are shadows stalking the land, the road coils like a snake. “A line of gulls has arrowed” suggesting an offensive, the Daphne du Maurier idea of birds turning on man, as well as the arrows of Amerindians fighting for survival. Time itself is pierced. Each turn of the poem (“a widening harbour”, “a town with no noise”, “streets growing closer”) is a stop along the way in a journey that is both linear and metaphorical. When “ancestral canoes” appear it is as though an Amerindian vessel has been excavated. We have crossed over. By the time we arrive at the closing lines (“a cloud slowly covers the page and it goes / white again and the book comes to a close”) we have been on a disorienting journey, travelling film-reel style through a country, through feelings (“white, silent surges”), through life and through ages. That the poem makes us think of the poetry book in our hands is not tangential to the theme of death that runs through the collection. For the poet is asking us to reflect on the place of objects in our lives and the relevance of objects in the afterlife.

Walcott simultaneously casts and breaks a spell: we succumb to the world of the poem, its lines and language but then the suspension of disbelief is broken. Suddenly there is a book in our hands. Poetry has seemingly engendered an object, the same object that provides its genesis. This is a return to the source of all poetry: the idea as the poet as a maker of things.

Throughout his long career, Walcott was coming closer and closer to the ideas he expresses here. The first version of this poem appeared in 2007 in The New York Review of Books under the heading, “This Page is a Cloud”. But long before that, in “Codicil”, published in 1965’s The Castaway, Walcott writes of a “clouding, unclouding sickle moon / whitening this beach again like a blank page”. The opening of 1973’s autobiographical Another Life also gives us:

Verandas, where the page of the seaare a book left open by an absent masterin the middle of another life–I begin here again,begin until this ocean’sa shut book…

Then in 1979’s The Star-Apple Kingdom we get “The Sea Is History” where, “the ocean kept turning blank pages”. The page is a metaphorical domain for landscape. But in 1987’s “To Norline” a relationship ends and, “when some line on a page / is loved… it’s hard to turn.” The stakes have been raised: the object in our hands is made into part of the poem, not just an idea within it. By 1997’s The Bounty, “cloud-pages close in amen” in response to a bequest.

This idea of the page as both a conjured and conjuring medium betrays the influence of Ted Hughes’ “The Thought Fox” where Hughes places his pastoral scene on “this blank page where my fingers move” and all the imagery climaxes with the declaration: “The page is printed”. Considering the latter poem’s own allusions to other poems such as Hopkin’s “The Windhover”, Blake’s “The Tyger”, and Coleridge’s “Frost at Midnight”, Walcott’s extension of the idea from page to book effortlessly suggests worlds within worlds, books within books, writers within writers. (Peter Gizzi’s “A page, we become” from his 1998 poem “Ledger Domain” also betrays a similar influence.)

It is no accident that Walcott ends White Egrets with this poem. Throughout the collection he surmises it will be his last book. He may have at one stage envisioned the poem as his last published piece. When his collected poems, The Poetry of Derek Walcott 1948 – 2013, appeared in 2014, the poem brought down the curtain. (The exhilarating lagniappe of Morning, Paramin, an ekphrastic work co-published with Peter Doig was yet to come.)

By punctuating his life’s work with this untitled poem, Walcott implicates us. He asks us the same questions Titus Hoyte does. Like a philosopher concerned with the relationship between ideas, language and reality, the poet uses the fraught process of reading to make us consider what is more real: language or what it describes? Life or death? A poet’s words, or the book that has been placed in our hands? When we close that book, what has happened to the poet and his words? And what has happened to us? Do we see the world around us afresh, as if born again? Or has something in that world changed? What is art if not a bridge between worlds? In my fantasy life, these are the kinds of questions I imagine Naipaul and Walcott arguing about over drinks like two tipsy characters in a novel or a play.

NAIPAUL’S NIGHTMARE

V.S. Naipaul wrote dozens of books but not the one with the most startling revelation about his life – The World Is What It Is, written by Patrick French and published in 2008. It generated headlines around the world. The Telegraph: “Sir Vidia Naipaul admits his cruelty may have killed wife”. The same paper, another report: “V.S. Naipaul, failing as a human being”. The Daily Mail: “Misogyny, mistresses and sadism”. The Atlantic: “Cruel and unusual”. The Economist: “Naked ambition”. All eyes were on Naipaul’s treatment of his first wife, his penchant for using prostitutes, his confirmation of a longstanding affair with an Argentinian woman, and, apparently, a sadomasochistic streak. Yet, tucked away in the book is a secret that possibly changes everything about the way we should see Naipaul, a secret that might even hold the key to some of the conduct covered by the headlines.

Everybody has an opinion on V.S. Naipaul, it seems, but do we really know him? The same man who during his lifetime was described as the greatest writer of English prose, even by his enemies, was the man who dismissed Jane Austen, Charles Dickens, E.M. Forster, James Joyce and more. The same man who won every literature prize imaginable, including the Nobel, was the man who was seen as racist, misogynistic, homophobic. The writer, some of whose fiction, such as A House for Mr Biswas, achieved a sublime lyrical humanity, was the same man who authored scornful reportage, throwing one-sided barbs at developing countries. Over time, critical views of literary reputation naturally wax and wane. The response to Naipaul’s novel The Enigma of Arrival flip-flopped dramatically during his lifetime. First described as “scarred by scrofula” by Derek Walcott and as a book without love by Salman Rushdie, it was later declared a “masterpiece” by the Nobel Prize committee. If Naipaul was a character in one of his novels we would be impressed, then confused by his complexity. Familiar yet unreachable, a Janus, a Jekyll and Hyde, a Dorian Grey – it is hard to see his real face. But the telling disclosure, that should not have been missed because it appears in the first fifty pages of French’s book, provides us with an important piece of the puzzle.

When Naipaul was six or seven his family moved to a cool, shady valley of forest and snakes. The place, to the north of Trinidad’s capital, was Petit Valley. It was yet another move for the Naipaul family and young Vidia was distraught. His grandmother tried to ease the transition. She told him how beautiful the new location was, how pleasing the big trees would be. Petit Valley was an estate of three hundred acres. An old colonial house stood on a green, forested hillside, surrounded by fruit trees: oranges, shaddocks, cacao, nutmeg, avocado, tangerines, mangoes. In this Eden, Vidia and his family lived in a separate, smaller house with a veranda, lit by oil lamps. One night, a fire began at the back of this wooden building. Vidia and his sister had to flee through a dark patch of forest. The Petit Valley is, of course, fictionalised as Shorthills in A House for Mr Biswas. V.S. Naipaul’s younger sister, Savi, has also written about this period in her memoir The Naipauls of Nepaul Street. The chapter title of her account, “Heidi of the Tropics” conveys her sense of the innocence of place and time.

According French’s book, it was around this time the molestation began.

“I was myself subjected to some sexual abuse by an older cousin. I was corrupted, I was assaulted,” Naipaul tells his biographer. “It was done in a sly terrible way and it gave me a hatred, a detestation of this homosexual thing.” We are told the molestation continued intermittently over the next two or three years, usually in the area where the boys slept. The perpetrator was a male cousin. Naipaul did not report it at the time or later:

“It was an outrage, but it was not a defining moment. I was very young. This thing was over before I was ten. I was always coerced. Of course he was ashamed too, later. It happened to other cousins. I think it is part of Indian extended family life, which is an abomination in some ways, a can of worms… After an assault one is very ashamed – and then you realise it happened to almost everybody. All children are abused. All girls are molested at some stage. It is almost like a rite of passage” (p. 36).

French’s interviews with Naipaul on this topic occurred in July and September 2002, indicating that Naipaul had kept this secret for six decades. I believe, contrary to Naipaul’s attempt to brush the matter off as simply incidental to Indian life, his characterization of these episodes as abuse, assault and molestation, his clear sense of shame, and the repeated nature of the violations over a prolonged period of time – whatever the complexities of his unwillingness or not – all suggest the matter was far from insignificant. I cannot believe he was not traumatised. There is perhaps some evidence of this in one of the childhood ailments that Naipaul suffered – terrifying asthma attacks.

As Faulkner said, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” Every person who has been subject to child abuse has a unique response. Trauma has an impact on the developing brain. Maltreated children sometimes grow up to become maltreating adults. Studies have linked child abuse to increased risk in later life of panic reactions, depression, anxiety, sexual dissatisfaction, promiscuity, stress, difficulty in controlling anger, intimate partner violence. A veiled cascade of response to a violation that is, because of its nature, hidden from view.

Naipaul always had a troubled relationship with Trinidad. Two years after the abuse ended he resolved to leave. He did. He fled by gaining a scholarship to Oxford. What was he trying to leave behind? Did he continue to carry whatever it was with him? At Oxford, he suffered a mental breakdown which, according to his first editor Diana Athill, involved some form of unspeakable horror which he never specified. But though Naipaul would later write of Trinidad in disparaging terms, it was a place he could never escape, a place he always returned to in his fiction, reportage, and in making regular returns to see his family, as we learn from Savi Akal-Naipaul’s memoir.

One of these returns was in 2007, five years after unburdening himself to French. When he visited his old college, he broke down in tears. When he was interviewed by the pro-vice chancellor of the local university, he cried. Elsewhere, he was irritable, intemperate, arrogant, cruel. It was all familiar behaviour. (The Chicago Tribune, in a headline, had once asked: “Why is V.S. Naipaul so cranky?”) I believe his famous prickliness in interviews, his querulous, harried demeanour, his pompous smugness were not merely attributable to a Trinidadian cantankerousness or propensity for the teasing mischief of picong. It was, rather, a state not inconsistent with being a victim of child abuse. Naipaul’s disposition towards Trinidad and his resultant worldview (in which he heaped scorn on similarly lessdeveloped nations), and his emotional breakdowns on returning to his birthplace, whether literally or in his writing, were all signs of someone being triggered by inner stress.

“I never want to go through my childhood again,” Naipaul told filmmaker Adam Low, though the aspects of his childhood that he chose to fictionalise in A House for Mr Biswas were the state of virtual homelessness and domestic disorder until the family’s arrival at Sikkim/Nepaul Street.

Jeremy Taylor has rightly observed, “Naipaul had to escape what he felt had been a nightmare childhood”. That impulse to leave was not just the practical impulse felt by a generation of Windrush writers who sought opportunities in Britain. Interviewed by Derek Walcott in Trinidad in 1965, Naipaul said, “I find this place very frightening. I think this is a very sinister place.” He was talking about what he saw as the damaging proletarianisation of Trinidadian life and culture, and no doubt alluding to the racial tribalism of the island. But such class warfare and racial strife are not unique to Trinidad. The intensity of his horror (“very frightening”, “very sinister”) indicates there was more in the mortar than the pestle.

Facts can be realigned, Naipaul once said, but fiction never lies. It reveals the writer totally. Inevitably, his crystalline prose laid bare his mental turmoil, even if a major source of the neurosis remained hidden. If abuse triggers abuse, it’s possible to see his treatment of his characters in a new light.

For example, in Guerillas, a book that imposes inventions over a true story, the complexity of the main female character is erased. Robert Hemenway finds her to be “savagely portrayed”, while Karl Miller notes “the novel breathes a certain animus” against her. Worse, the narrative adopts a fatalistic tone to her brutal murder. As much as we’d like to believe Naipaul is applying a journalistic approach to the thinly disguised real-life events behind the story, it’s equally possible to argue he is throwing up the idea of Jane’s fate being a form of justice because of failings and self-deceptions in her character. In other words, victim-shaming by innuendo. Perhaps tellingly, anal sex is framed as a special kind of degradation. And a child being raped becomes part of an elaborate fantasy dreamed up by a male protagonist, Jimmy Ahmed.

In A Bend in the River, Salim, a frequenter of female prostitutes in brothels, grows fond of sex that is “full of deliberate brutality”, and in one scene beats a woman before having sex with her. In Half a Life there is talk of the fingering then rape of little girls. In Magic Seeds, a woman begs the main character to use a belt on her.

“Why does Naipaul create such scenes?” Robert Hemenway asks. The answer is possibly this: he was perpetually mirroring his abuse and its effects.

By way of contrast, in Naipaul’s biggest and most autobiographical book, A House for Mr Biswas, written relatively early at the age of 29, the attention given to the sexual lives of characters is relatively paltry. The novel’s artistic structure focuses on the figure of the father, Mr Biswas; this in itself guarantees that the novel does not deal with any latent sexual issues relating to the son, Anand. If there was suppression here, later work suggests that, as time passed, the need to revisit the Petit Valley’s abuse gradually irrupted in the writing. Consider this moment from “A Flag in the Island” (1967), Naipaul’s story about a former US marine ashore in Trinidad, in which the narrative suddenly ruptures, with a reflection on the terrors of childhood:

This is part of my mood; it heightens my anxiety; I feel the whole world being washed away and that I am being washed away with it. I feel my time is short. The child, testing his courage, steps into the swiftly moving stream, and though the water does not go above his ankles, in an instant the safe solid earth vanishes and he is aware only of the terror of sky and trees and the force at his feet” (pp. 479-480).

Naipaul’s conflict when it comes to the factual details of his life mirrors these undercurrents. Torn, he vacillated between outwardly stating his distaste for writing an autobiography and actually writing such an autobiography under the permissive guise of fiction. Indeed, he was praised for blurring the line between autobiography and fiction, for pushing the novel to its limits, such as in his Booker prizewinning In A Free State. Still, even when he turned from the pretences of storytelling to reportage on the factual world, we get glimmers of his trauma. Murder will out. Here is Naipaul’s description, in his first travel book, The Middle Passage, of making a return voyage to Trinidad:

I began to feel my old fear of Trinidad. I did not want to stay… When I was in the fourth form I wrote a vow on the endpaper of my Kennedy’s Revised LatinPrimer to leave within five years. I left after six; and for many years afterwards in England, falling asleep in bedsitters with the electric fire on, I had been awakened by the nightmare that I was back in tropical Trinidad. (pp. 33-34)

Consider, too, this disclosure from his preface to An Area of Darkness:

I was saved by the deeper anxiety that had been with me throughout the journey to India. This anxiety was that after A House for Mr Biswas I had run out of fictional material and that life was going to be very hard for me in the future; perhaps the writing career would have to stop. This anxiety took various forms, some mental, some physical, some a combination of the two. The most debilitating anxiety was that I was losing the gift of speech. It was at the back of everything I did. (p.6)

Often, in works of art, such as Alfred Hitchcock’s film, Rope (1948), what appears to be one kind of story turns out to be a code for something else. In the case of that film the criminal enterprise at its heart is a cipher for homosexuality. In a similar way, Naipaul’s intense anxieties, which he attributed to a fear of his writing career coming to an end, point not just to the precarious nature of a creative life, they point to a past that held sway over him. This past, this trauma, migrated to his fiction, influenced his political views, shaped the attitudes expressed in his non-fiction and interviews. I believe the trauma also bled into his private life and his relations with people. Even the author’s seemingly innocuous choice of a home in the green and leafy countryside of Wiltshire, described hypnotically in The Enigma of Arrival, was a return to the verdant site of an inescapable wounding, a movement away from the urban landscape of London to the countryside, a repeat of his family’s temporary retreat from the densely-packed suburb of Woodbrook to the hills to the north of Port of Spain.

But is this too simple? Too novelistic, even? It’s no doubt unwise to try to reduce entire lives to a single set of motivations, impulses and events. And why didn’t French, Naipaul’s own biographer, make more of the disclosures in The World Is What It Is? The biographer spends one page out of five-hundred on the matter, then moves on. We get the feeling the incident was written off as perhaps nothing more than experimentation of some sort, or an affirmation of the old adage, “boys will be boys”.

Yet, to isolate a single thread is not to present a simplistic solution to this riddle. It is to tease out the complexity of the overall writing personality. And there is a lot of complexity.

For instance, what are we to make of Naipaul’s views on women writers? On the one hand he could declare, “I read a piece of writing and within a paragraph or two I know whether it is by a woman or not.” On the other hand, this is a writer who openly professed to relying heavily on the judgment of women to produce his own books. Everything he wrote was first read by his wives. At his first publisher, where he published his early masterworks, he was edited by a woman. Publicly he could dismiss Jane Austen as being an example of her class: a female writer having a “sentimental view of the world”, while behind closed doors he subjected his manuscripts to vetting by the women closest to him. Naipaul’s treatment of queerness, too, is similarly contradictory.

Naipaul was not really on my gaydar as I grew up gay in Trinidad. I only began to take a closer look after he won the Nobel Prize in 1992 and after reading his short story “Tell Me Who To Kill”.

We turn to literature both to see the world, and to see ourselves. As a child I turned to representations of gay characters in all mediums. I looked for independent verification, for corroboration and affirmation of my own dignity. I was drawn to something in “Tell Me Who To Kill”, even if I was not yet to understand it fully. The handling of the material, the characters – it was all suffused with an aura of innuendo and implication surrounding the relationship between the male narrator and his friend, Frank. We get the sense we are reading the germ of a novel. There is no real story. The piece is more about mood. Its journey is cinematographic, its tone film noir. There are surreal flashbacks, scenes of peril and dread. This is intensified by the presence, the ghost perhaps, of the real-life story of two Trinidadian Indian brothers who, not long before Naipaul wrote the story between August 1969 and October 1970, became infamous for a murder. The details of the case of Arthur and Nizamodeen Hosein were darkly comic (except to the unfortunate murdered woman and her family); they kidnapped the wrong person, according to trial prosecutors. Naipaul’s story does not exploit that kind of tragic absurdity, but he very probably drew on the trial narrative of the picture of influence and dependence between the Hosein brothers. Into the mix must also be added the possibility that Naipaul reflected and drew upon his troubled relationship with his younger brother Shiva. Through all of the fog, the narrator’s strong quasi-homosexual bond with his white friend, Frank, stands out:

Frank touch me on the arm. I am glad he touch me, but I shrug his hand away. I know it isn’t true, but I tell myself he is on the other side, with the others, looking at me without looking at me. I know it isn’t true about Frank because, look, he too is nervous. He want to be alone with me; he don’t like being with his own people. It isn’t like being on a bus or in a café, where he can be like a man saying: I protect this man with me. (p. 99)

The story ends just before a wedding, but it is not a celebration of the homosexual couple. On the contrary, by its concluding line, which makes reference to Rope, the piece has followed a long homophobic tradition of linking queerness to mental instability and criminality.

The more I read Naipaul, the more I found signs of a curiosity about and concern for gay characters, though the gay characters who appear within the folds of his narratives are not fleshed out and granted the complexity of real people – and are invariably served tragic ends.

So Bobby in In a Free State is humiliated, denuded, his face rubbed against the floor, his wrist broken by soldiers. Alan in The Enigma of Arrival dies of a drug overdose.

In Guerillas, Bryant goes crazy, Jimmy is crazy. They become murderers. Conforming to the stereotype of queerness being pitted against masculinity, Leonard Side in A Way in the World is described as a “decorator of cakes” who works “all his life with flowers”. We are introduced to him as a man, “doing things to a dead body on a table or slab in front of him” with “hairy fingers”. He falls ill. We never learn if he survives this illness; the nebulous implication is death could well have been his fate. This is a work of fiction but his character is apparently not even deserving of that kind of basic resolution. A school teacher, whose only function in the book is to tell us about Leonard, describes Leonard thus: “He frightened me because I felt his feeling for beauty was like an illness; as though some unfamiliar, deforming virus had passed through his simple mother to him” (pp. 7-8 ).

In the Caribbean and in many parts of the world still hostile to LGBTQ rights, homosexuality is maliciously and simplistically linked to paedophilia and child abuse. Did Naipaul make that link in his mind? Could this explain his homophobia? His dismissal of E.M. Forster and John Maynard Keynes as nasty homosexuals?

Or, given how Naipaul’s generation dealt with homosexuality, could Naipaul himself have had a more complex relationship with the idea of same-sex desire? Is it possible that his own homophobia was to some extent the expression of internalised conflict, directed at nascent tendencies, tendencies which then triggered shame and self-loathing and the desire to violently squash the legitimacy of such feelings?

I hold no brief for Naipaul’s homophobia. I don’t think it can be justified or excused. Instead, I want to ask questions. I want to observe, as was observed of Hamlet’s mother, that Naipaul doth protest too much.

Some years after Naipaul’s discussion with his biographer, his sister Kamla, who held his hand in Petit Valley the night they ran through the forest from the fire, confirmed that Naipaul had never spoken to her about the abuse.

“I didn’t know about this. Because if I did I would have been mad like hell. I would have been extremely annoyed. Nothing was told to me,” she said to Newsday. Like many others, she did not think the experience affected her brother’s life.

“He’s not easily worried by something like that,” she said. But is it really possible not to be “worried by something like that”? Naipaul’s sensitivity is legendary. For instance, he famously declined to read his own letters to his father, even when they were being collated for publication.

“Certain things are so painful one prefers not to be reminded of them,” Naipaul told broadcaster Charlie Rose. Is it really possible to assume that a person, who could become paralysed at the thought of reading correspondence from his earlier life, could simply turn off the tap when it came to his experience of child abuse?

Not only did Naipaul manifest the lingering effects in his writing, people around him knew something was up.

“Vidia’s anxiety and despair were real: you need only compare a photograph of his face in his twenties with one taken in his forties to see how it had been shaped by pain,” wrote Athill in her famous Granta essay on editing Naipaul. “It was my job to listen to his unhappiness and do what I could to ease it – which would not have been too bad if there had been anything I could do.”

Something of this anxiety and despair stalks the writing. It’s channelled in “Tell Me Who to Kill” where, as noted, Naipaul suffuses the story with the doom and gloom of Rope. He punctuates the narrative with a dazzling array of film references that perform key functions in the narrative. Consider the first mention of a film; it helps us build a psychological profile of the narrator:

And it is as though you are frightened of something it is bound to come, as though because you are carrying danger with you danger is bound to come. And again it is like a dream. I see myself in this old English house, like something in Rebecca starring Laurence Oliver and Joan Fountain. It is an upstairs room with a lot of jalousies and fretwork. No weather. I am there with my brother, and we are strangers in the house. (p. 62)

The film version of Daphne du Maurier’s novel Rebecca is a love story that follows a woman who marries a man, only to find out that she will always be in the shadow of his first wife who died in mysterious circumstances. The reference to fretwork and jalousies is a refraction of the gingerbread houses of Trinidad from which the narrator originates. Importantly, Rebecca is a film featuring many twists and turns and sinister elements that conspire to deceive and smother the woman. The sense of unseen danger, of helplessness, may be transposed to Naipaul’s protagonist. Houses are always important symbols, particularly from the author of A House for Mr Biswas, but the line, “we are strangers in the house” echoes the title of another suspenseful Hitchcock film, Strangers on a Train (1951), where two men plot murder. In this story, another early film reference shows how the protagonist has used movies to map London’s urban landscape. His vision of what the city is supposed to look like has come partially from Waterloo Bridge, named after the famous bridge off the Strand:

I used to have a vision of a big city. It wasn’t like this, not streets like this. I used to see a pretty park with high black iron railings like spears, old thick trees growing out of the wide pavement, rain falling the way it fall over Robert Taylor in Waterloo Bridge, and the pavement covered with flat leaves of a perfect shape in pretty colours, gold and red and crimson. (p. 72)

Waterloo Bridge (1940) is a noirish film about a ballerina who kills herself. All of the films feature characters in love or with secrets or both, and these secrets in different ways threaten to engulf and destroy them. This is true of Jesse James (1939), and, very true of Rope, which dominates the short story. In an extended fantasy sequence, the narrator imagines something tragic happening, something which must be concealed and covered up by him and by his beloved, his brother, Dayo. As with most Hitchcock films, this tragic incident appears to come out of nowhere and embroils an ordinary person who must move from a banal situation into one of extraordinary peril. In a dream sequence, the narrator takes us to a place somewhere proximate to the house in Rebecca and tells us of “a quarrel, a friendly argument, a scuffle” involving a friend of Dayo that results in a murder. The details are only telegraphed; we learn the boys “are only playing, but the knife go in the boy, easy.” The narrator says:

And the body is in the house, in a chest, like in Rope with Fairley Granger. It is there at the beginning, it is there forever, and everything else is only like a mockery. But we eat. My brother is trembling; he is not a good actor. The people we are eating with, I can’t see their faces, I don’t know what they look like. (pp. 62-63)

The second Rope reference occurs with the reappearance of “Fairley Granger” – or Farley Granger – whose hairstyle is compared to Dayo’s. Then the imagined encounter with the friend of Dayo – now described as a college friend – recurs and again death comes. Again when a penetrating knife goes in, “it is an accident” and, “The body is in the chest, like in Rope, but in this English house.” The entire story ends, in film-reel fashion, with a panoramic sweep of several images that have dotted the narrative and a fourth and final reference to Rope:

I have my own place to go back to. Frank will take me there when this is over. And now that my brother leave me for good I forget his face already, and I only seeing the rain and the house and the mud, the field at the back with the pará-grass bending down with the rain, the donkey and the smoke from the kitchen, my father in the gallery and my brother in the room on the floor and that boy opening his mouth to scream, like in Rope. (pp. 107-108)

All these ciphers, all these codes hang over “Tell Me Who to Kill”, giving powerful weight to the unnamed narrator’s heart-breaking declaration: “I only know that inside me mash up, and that the love and danger I carry all this time break and cut, and my life finish.” As he considers his past and his alienated present there is no fighting spirit as suggested by the title. Instead, traumatised, he declares, “I am the dead man.”

I once attended an event in Trinidad to commemorate Derek Walcott. Members of the audience were invited to ask questions. In posing a question, someone mentioned Naipaul’s name. Immediately there was a noisy uproar. It became clear that the mere mention of his name can still trigger strong emotions. I saw a similar thing when, weeks later, I chaired a discussion panel at the Bocas Lit Fest on Naipaul in downtown Port of Spain. Some people strongly defend him. Others excoriate him. None can ignore him.