0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

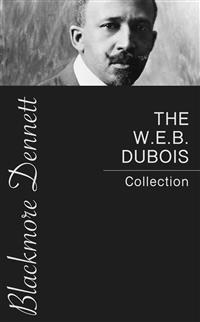

- Herausgeber: Blackmore Dennett

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

W.E.B. Dubois was an American sociologist, historian, civil rights activist, Pan-Africanist, author, writer and editor. Born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, Du Bois grew up in a relatively tolerant and integrated community, and after completing graduate work at the University of Berlin and Harvard, where he was the first African American to earn a doctorate, he became a professor of history, sociology and economics at Atlanta University. Du Bois was one of the founders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1909.

The W.E.B. Dubois Collection features:

The Quest Of The Silver Fleece: A Novel

The Souls Of Black Folk

The Talented Tenth

The Conservation Of Races

The Suppression Of The African Slave Trade To The United States Of America, 1638-1870

The Negro

The Negro In The South

and

Darkwater: Voices From Within The Veil

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

THE

W.E.B. DUBOIS

COLLECTION

Published 2019 by Blackmore Dennett

All rights reserved. This book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the publisher except for the use of brief quotations in a book review.

Thank you for your purchase. If you enjoyed this work, please leave us a comment.

1 2 3 4 10 8 7 6 5 00 000

Also available from Blackmore Dennett:

TABLE OF CONTENTS

THE QUEST OF THE SILVER FLEECE: A NOVEL

NOTE

CHAPTER ONE: DREAMS

CHAPTER TWO: THE SCHOOL

CHAPTER THREE: MISS MARY TAYLOR

CHAPTER FOUR: TOWN

CHAPTER FIVE: ZORA

CHAPTER SIX: COTTON

CHAPTER SEVEN: THE PLACE OF DREAMS

CHAPTER EIGHT: MR. HARRY CRESSWELL

CHAPTER NINE: THE PLANTING

CHAPTER TEN: MR. TAYLOR CALLS

CHAPTER ELEVEN: THE FLOWERING OF THE FLEECE

CHAPTER TWELVE: THE PROMISE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN: MRS. GREY GIVES A DINNER

CHAPTER FOURTEEN: LOVE

CHAPTER FIFTEEN: REVELATION

CHAPTER SIXTEEN: THE GREAT REFUSAL

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN: THE RAPE OF THE FLEECE

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN: THE COTTON CORNER

CHAPTER NINETEEN: THE DYING OF ELSPETH

CHAPTER TWENTY: THE WEAVING OF THE SILVER FLEECE

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE: THE MARRIAGE MORNING

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO: MISS CAROLINE WYNN

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE: THE TRAINING OF ZORA

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR: THE EDUCATION OF ALWYN

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE: THE CAMPAIGN

CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX: CONGRESSMAN CRESSWELL

CHAPTER TWENTY-SEVEN – THE VISION OF ZORA

CHAPTER TWENTY-EIGHT: THE ANNUNCIATION

CHAPTER TWENTY-NINE: A MASTER OF FATE

CHAPTER THIRTY: THE RETURN OF ZORA

CHAPTER THIRTY-ONE: A PARTING OF WAYS

CHAPTER THIRTY-TWO: ZORA’S WAY

CHAPTER THIRTY-THREE: THE BUYING OF THE SWAMP

CHAPTER THIRTY-FOUR: THE RETURN OF ALWYN

CHAPTER THIRTY-FIVE : THE COTTON MILL

CHAPTER THIRTY-SIX: THE LAND

CHAPTER THIRTY-SEVEN: THE MOB

CHAPTER THIRTY-EIGHT: ATONEMENT

L’ENVOI

THE SOULS OF BLACK FOLK

THE FORETHOUGHT

I - OF OUR SPIRITUAL STRIVINGS

II - OF THE DAWN OF FREEDOM

III - OF MR. BOOKER T. WASHINGTON AND OTHERS

IV - OF THE MEANING OF PROGRESS

V - OF THE WINGS OF ATALANTA

VI - OF THE TRAINING OF BLACK MEN

VII - OF THE BLACK BELT

VIII - OF THE QUEST OF THE GOLDEN FLEECE

IX - OF THE SONS OF MASTER AND MAN

X - OF THE FAITH OF THE FATHERS

XI - OF THE PASSING OF THE FIRST-BORN

XII - OF ALEXANDER CRUMMELL

XIII - OF THE COMING OF JOHN

XIV - OF THE SORROW SONGS

THE AFTERTHOUGHT

THE TALENTED TENTH

THE CONSERVATION OF RACES

ANNOUNCEMENT

THE CONSERVATION OF RACES

THE SUPPRESSION OF THE AFRICAN SLAVE TRADE TO THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, 1638-1870

VOLUME I

PREFACE

CHAPTER I - INTRODUCTORY.

CHAPTER II - THE PLANTING COLONIES.

CHAPTER III - THE FARMING COLONIES.

CHAPTER IV - THE TRADING COLONIES.

CHAPTER V - THE PERIOD OF THE REVOLUTION.

CHAPTER VI - THE FEDERAL CONVENTION.

CHAPTER VII - TOUSSAINT L’OUVERTURE AND ANTI-SLAVERY EFFORT,

CHAPTER VIII - THE PERIOD OF ATTEMPTED SUPPRESSION.

CHAPTER IX - THE INTERNATIONAL STATUS OF THE SLAVE-TRADE.

CHAPTER X - THE RISE OF THE COTTON KINGDOM.

CHAPTER XI - THE FINAL CRISIS.

CHAPTER XII - THE ESSENTIALS IN THE STRUGGLE.

APPENDIX A.

APPENDIX B.

APPENDIX C.

APPENDIX D.

FOOTNOTES

THE NEGRO

PREFACE

I: AFRICA

II: THE COMING OF BLACK MEN

III: ETHIOPIA AND EGYPT

IV: THE NIGER AND ISLAM

V: GUINEA AND CONGO

VI: THE GREAT LAKES AND ZYMBABWE

VII: THE WAR OF RACES AT LAND’S END

VIII: AFRICAN CULTURE

IX: THE TRADE IN MEN

X: THE WEST INDIES AND LATIN AMERICA

XI: THE NEGRO IN THE UNITED STATES

XII: THE NEGRO PROBLEMS

THE NEGRO IN THE SOUTH

CHAPTER I: THE ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT OF THE NEGRO RACE IN SLAVERY

CHAPTER II: THE ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT OF THE NEGRO RACE SINCE ITS EMANCIPATION

CHAPTER III: THE ECONOMIC REVOLUTION IN THE SOUTH

CHAPTER IV: RELIGION IN THE SOUTH

DARKWATER: VOICES FROM WITHIN THE VEIL

POSTSCRIPT

CREDO

I - THE SHADOW OF YEARS

A LITANY AT ATLANTA

II - THE SOULS OF WHITE FOLK

THE RIDDLE OF THE SPHINX

III - THE HANDS OF ETHIOPIA

THE PRINCESS OF THE HITHER ISLES

IV - OF WORK AND WEALTH

THE SECOND COMING

V - “THE SERVANT IN THE HOUSE”

JESUS CHRIST IN TEXAS

VI - OF THE RULING OF MEN

THE CALL

VII - THE DAMNATION OF WOMEN

CHILDREN OF THE MOON

VIII-THE IMMORTAL CHILD

IX - OF BEAUTY AND DEATH

THE PRAYERS OF GOD

X - THE COMET

A HYMN TO THE PEOPLES

THE QUEST OF THE SILVER FLEECE: A NOVEL

..................

NOTE

..................

HE WHO WOULD TELL A tale must look toward three ideals: to tell it well, to tell it beautifully, and to tell the truth.

The first is the Gift of God, the second is the Vision of Genius, but the third is the Reward of Honesty.

In The Quest of the Silver Fleece there is little, I ween, divine or ingenious; but, at least, I have been honest. In no fact or picture have I consciously set down aught the counterpart of which I have not seen or known; and whatever the finished picture may lack of completeness, this lack is due now to the story-teller, now to the artist, but never to the herald of the Truth.

NEW YORK CITY

August 15, 1911

THE AUTHOR

CHAPTER ONE: DREAMS

..................

NIGHT FELL. THE RED WATERS of the swamp grew sinister and sullen. The tall pines lost their slimness and stood in wide blurred blotches all across the way, and a great shadowy bird arose, wheeled and melted, murmuring, into the black-green sky.

The boy wearily dropped his heavy bundle and stood still, listening as the voice of crickets split the shadows and made the silence audible. A tear wandered down his brown cheek. They were at supper now, he whispered—the father and old mother, away back yonder beyond the night. They were far away; they would never be as near as once they had been, for he had stepped into the world. And the cat and Old Billy—ah, but the world was a lonely thing, so wide and tall and empty! And so bare, so bitter bare! Somehow he had never dreamed of the world as lonely before; he had fared forth to beckoning hands and luring, and to the eager hum of human voices, as of some great, swelling music.

Yet now he was alone; the empty night was closing all about him here in a strange land, and he was afraid. The bundle with his earthly treasure had hung heavy and heavier on his shoulder; his little horde of money was tightly wadded in his sock, and the school lay hidden somewhere far away in the shadows. He wondered how far it was; he looked and harkened, starting at his own heartbeats, and fearing more and more the long dark fingers of the night.

Then of a sudden up from the darkness came music. It was human music, but of a wildness and a weirdness that startled the boy as it fluttered and danced across the dull red waters of the swamp. He hesitated, then impelled by some strange power, left the highway and slipped into the forest of the swamp, shrinking, yet following the song hungrily and half forgetting his fear. A harsher, shriller note struck in as of many and ruder voices; but above it flew the first sweet music, birdlike, abandoned, and the boy crept closer.

The cabin crouched ragged and black at the edge of black waters. An old chimney leaned drunkenly against it, raging with fire and smoke, while through the chinks winked red gleams of warmth and wild cheer. With a revel of shouting and noise, the music suddenly ceased. Hoarse staccato cries and peals of laughter shook the old hut, and as the boy stood there peering through the black trees, abruptly the door flew open and a flood of light illumined the wood.

Amid this mighty halo, as on clouds of flame, a girl was dancing. She was black, and lithe, and tall, and willowy. Her garments twined and flew around the delicate moulding of her dark, young, half-naked limbs. A heavy mass of hair clung motionless to her wide forehead. Her arms twirled and flickered, and body and soul seemed quivering and whirring in the poetry of her motion.

As she danced she sang. He heard her voice as before, fluttering like a bird’s in the full sweetness of her utter music. It was no tune nor melody, it was just formless, boundless music. The boy forgot himself and all the world besides. All his darkness was sudden light; dazzled he crept forward, bewildered, fascinated, until with one last wild whirl the elf-girl paused. The crimson light fell full upon the warm and velvet bronze of her face—her midnight eyes were aglow, her full purple lips apart, her half hid bosom panting, and all the music dead. Involuntarily the boy gave a gasping cry and awoke to swamp and night and fire, while a white face, drawn, red-eyed, peered outward from some hidden throng within the cabin.

“Who’s that?” a harsh voice cried.

“Where?” “Who is it?” and pale crowding faces blurred the light.

The boy wheeled blindly and fled in terror stumbling through the swamp, hearing strange sounds and feeling stealthy creeping hands and arms and whispering voices. On he toiled in mad haste, struggling toward the road and losing it until finally beneath the shadows of a mighty oak he sank exhausted. There he lay a while trembling and at last drifted into dreamless sleep.

It was morning when he awoke and threw a startled glance upward to the twisted branches of the oak that bent above, sifting down sunshine on his brown face and close curled hair. Slowly he remembered the loneliness, the fear and wild running through the dark. He laughed in the bold courage of day and stretched himself.

Then suddenly he bethought him again of that vision of the night—the waving arms and flying limbs of the girl, and her great black eyes looking into the night and calling him. He could hear her now, and hear that wondrous savage music. Had it been real? Had he dreamed? Or had it been some witch-vision of the night, come to tempt and lure him to his undoing? Where was that black and flaming cabin? Where was the girl—the soul that had called him? She must have been real; she had to live and dance and sing; he must again look into the mystery of her great eyes. And he sat up in sudden determination, and, lo! gazed straight into the very eyes of his dreaming.

She sat not four feet from him, leaning against the great tree, her eyes now languorously abstracted, now alert and quizzical with mischief. She seemed but half-clothed, and her warm, dark flesh peeped furtively through the rent gown; her thick, crisp hair was frowsy and rumpled, and the long curves of her bare young arms gleamed in the morning sunshine, glowing with vigor and life. A little mocking smile came and sat upon her lips.

“What you run for?” she asked, with dancing mischief in her eyes.

“Because—” he hesitated, and his cheeks grew hot.

“I knows,” she said, with impish glee, laughing low music.

“Why?” he challenged, sturdily.

“You was a-feared.”

He bridled. “Well, I reckon you’d be a-feared if you was caught out in the black dark all alone.”

“Pooh!” she scoffed and hugged her knees. “Pooh! I’ve stayed out all alone heaps o’ nights.”

He looked at her with a curious awe.

“I don’t believe you,” he asserted; but she tossed her head and her eyes grew scornful.

“Who’s a-feared of the dark? I love night.” Her eyes grew soft.

He watched her silently, till, waking from her daydream, she abruptly asked:

“Where you from?”

“Georgia.”

“Where’s that?”

He looked at her in surprise, but she seemed matter-of-fact.

“It’s away over yonder,” he answered.

“Behind where the sun comes up?”

“Oh, no!”

“Then it ain’t so far,” she declared. “I knows where the sun rises, and I knows where it sets.” She looked up at its gleaming splendor glinting through the leaves, and, noting its height, announced abruptly:

“I’se hungry.”

“So’m I,” answered the boy, fumbling at his bundle; and then, timidly: “Will you eat with me?”

“Yes,” she said, and watched him with eager eyes.

Untying the strips of cloth, he opened his box, and disclosed chicken and biscuits, ham and corn-bread. She clapped her hands in glee.

“Is there any water near?” he asked.

Without a word, she bounded up and flitted off like a brown bird, gleaming dull-golden in the sun, glancing in and out among the trees, till she paused above a tiny black pool, and then came tripping and swaying back with hands held cupwise and dripping with cool water.

“Drink,” she cried. Obediently he bent over the little hands that seemed so soft and thin. He took a deep draught; and then to drain the last drop, his hands touched hers and the shock of flesh first meeting flesh startled them both, while the water rained through. A moment their eyes looked deep into each other’s—a timid, startled gleam in hers; a wonder in his. Then she said dreamily:

“We’se known us all our lives, and—before, ain’t we?”

He hesitated.

“Ye—es—I reckon,” he slowly returned. And then, brightening, he asked gayly: “And we’ll be friends always, won’t we?”

“Yes,” she said at last, slowly and solemnly, and another brief moment they stood still.

Then the mischief danced in her eyes, and a song bubbled on her lips. She hopped to the tree.

“Come—eat!” she cried. And they nestled together amid the big black roots of the oak, laughing and talking while they ate.

“What’s over there?” he asked pointing northward.

“Cresswell’s big house.”

“And yonder to the west?”

“The school.”

He started joyfully.

“The school! What school?”

“Old Miss’ School.”

“Miss Smith’s school?”

“Yes.” The tone was disdainful.

“Why, that’s where I’m going. I was a-feared it was a long way off; I must have passed it in the night.”

“I hate it!” cried the girl, her lips tense.

“But I’ll be so near,” he explained. “And why do you hate it?”

“Yes—you’ll be near,” she admitted; “that’ll be nice; but—” she glanced westward, and the fierce look faded. Soft joy crept to her face again, and she sat once more dreaming.

“Yon way’s nicest,” she said.

“Why, what’s there?”

“The swamp,” she said mysteriously.

“And what’s beyond the swamp?”

She crouched beside him and whispered in eager, tense tones: “Dreams!”

He looked at her, puzzled.

“Dreams?” vaguely—”dreams? Why, dreams ain’t—nothing.”

“Oh, yes they is!” she insisted, her eyes flaming in misty radiance as she sat staring beyond the shadows of the swamp. “Yes they is! There ain’t nothing but dreams—that is, nothing much.

“And over yonder behind the swamps is great fields full of dreams, piled high and burning; and right amongst them the sun, when he’s tired o’ night, whispers and drops red things, ‘cept when devils make ‘em black.”

The boy stared at her; he knew not whether to jeer or wonder.

“How you know?” he asked at last, skeptically.

“Promise you won’t tell?”

“Yes,” he answered.

She cuddled into a little heap, nursing her knees, and answered slowly.

“I goes there sometimes. I creeps in ‘mongst the dreams; they hangs there like big flowers, dripping dew and sugar and blood—red, red blood. And there’s little fairies there that hop about and sing, and devils—great, ugly devils that grabs at you and roasts and eats you if they gits you; but they don’t git me. Some devils is big and white, like ha’nts; some is long and shiny, like creepy, slippery snakes; and some is little and broad and black, and they yells—”

The boy was listening in incredulous curiosity, half minded to laugh, half minded to edge away from the black-red radiance of yonder dusky swamp. He glanced furtively backward, and his heart gave a great bound.

“Some is little and broad and black, and they yells—” chanted the girl. And as she chanted, deep, harsh tones came booming through the forest:

“Zo-ra! Zo-ra! O—o—oh, Zora!”

He saw far behind him, toward the shadows of the swamp, an old woman—short, broad, black and wrinkled, with fangs and pendulous lips and red, wicked eyes. His heart bounded in sudden fear; he wheeled toward the girl, and caught only the uncertain flash of her garments—the wood was silent, and he was alone.

He arose, startled, quickly gathered his bundle, and looked around him. The sun was strong and high, the morning fresh and vigorous. Stamping one foot angrily, he strode jauntily out of the wood toward the big road.

But ever and anon he glanced curiously back. Had he seen a haunt? Or was the elf-girl real? And then he thought of her words:

“We’se known us all our lives.”

CHAPTER TWO: THE SCHOOL

..................

DAY WAS BREAKING ABOVE THE white buildings of the Negro school and throwing long, low lines of gold in at Miss Sarah Smith’s front window. She lay in the stupor of her last morning nap, after a night of harrowing worry. Then, even as she partially awoke, she lay still with closed eyes, feeling the shadow of some great burden, yet daring not to rouse herself and recall its exact form; slowly again she drifted toward unconsciousness.

“Bang! bang! bang!” hard knuckles were beating upon the door below.

She heard drowsily, and dreamed that it was the nailing up of all her doors; but she did not care much, and but feebly warded the blows away, for she was very tired.

“Bang! bang! bang!” persisted the hard knuckles.

She started up, and her eye fell upon a letter lying on her bureau. Back she sank with a sigh, and lay staring at the ceiling—a gaunt, flat, sad-eyed creature, with wisps of gray hair half-covering her baldness, and a face furrowed with care and gathering years.

It was thirty years ago this day, she recalled, since she first came to this broad land of shade and shine in Alabama to teach black folks.

It had been a hard beginning with suspicion and squalor around; with poverty within and without the first white walls of the new school home. Yet somehow the struggle then with all its helplessness and disappointment had not seemed so bitter as today: then failure meant but little, now it seemed to mean everything; then it meant disappointment to a score of ragged urchins, now it meant two hundred boys and girls, the spirits of a thousand gone before and the hopes of thousands to come. In her imagination the significance of these half dozen gleaming buildings perched aloft seemed portentous—big with the destiny not simply of a county and a State, but of a race—a nation—a world. It was God’s own cause, and yet—

“Bang! bang! bang!” again went the hard knuckles down there at the front.

Miss Smith slowly arose, shivering a bit and wondering who could possibly be rapping at that time in the morning. She sniffed the chilling air and was sure she caught some lingering perfume from Mrs. Vanderpool’s gown. She had brought this rich and rare-apparelled lady up here yesterday, because it was more private, and here she had poured forth her needs. She had talked long and in deadly earnest. She had not spoken of the endowment for which she had hoped so desperately during a quarter of a century—no, only for the five thousand dollars to buy the long needed new land. It was so little—so little beside what this woman squandered—

The insistent knocking was repeated louder than before.

“Sakes alive,” cried Miss Smith, throwing a shawl about her and leaning out the window. “Who is it, and what do you want?”

“Please, ma’am. I’ve come to school,” answered a tall black boy with a bundle.

“Well, why don’t you go to the office?” Then she saw his face and hesitated. She felt again the old motherly instinct to be the first to welcome the new pupil; a luxury which, in later years, the endless push of details had denied her.

“Wait!” she cried shortly, and began to dress.

A new boy, she mused. Yes, every day they straggled in; every day came the call for more, more—this great, growing thirst to know—to do—to be. And yet that woman had sat right here, aloof, imperturbable, listening only courteously. When Miss Smith finished, she had paused and, flicking her glove,—

“My dear Miss Smith,” she said softly, with a tone that just escaped a drawl—”My dear Miss Smith, your work is interesting and your faith—marvellous; but, frankly, I cannot make myself believe in it. You are trying to treat these funny little monkeys just as you would your own children—or even mine. It’s quite heroic, of course, but it’s sheer madness, and I do not feel I ought to encourage it. I would not mind a thousand or so to train a good cook for the Cresswells, or a clean and faithful maid for myself—for Helene has faults—or indeed deft and tractable laboring-folk for any one; but I’m quite through trying to turn natural servants into masters of me and mine. I—hope I’m not too blunt; I hope I make myself clear. You know, statistics show—”

“Drat statistics!” Miss Smith had flashed impatiently. “These are folks.”

Mrs. Vanderpool smiled indulgently. “To be sure,” she murmured, “but what sort of folks?”

“God’s sort.”

“Oh, well—”

But Miss Smith had the bit in her teeth and could not have stopped. She was paying high for the privilege of talking, but it had to be said.

“God’s sort, Mrs. Vanderpool—not the sort that think of the world as arranged for their exclusive benefit and comfort.”

“Well, I do want to count—”

Miss Smith bent forward—not a beautiful pose, but earnest.

“I want you to count, and I want to count, too; but I don’t want us to be the only ones that count. I want to live in a world where every soul counts—white, black, and yellow—all. That’s what I’m teaching these children here—to count, and not to be like dumb, driven cattle. If you don’t believe in this, of course you cannot help us.”

“Your spirit is admirable, Miss Smith,” she had said very softly; “I only wish I could feel as you do. Good-afternoon,” and she had rustled gently down the narrow stairs, leaving an all but imperceptible suggestion of perfume. Miss Smith could smell it yet as she went down this morning.

The breakfast bell jangled. “Five thousand dollars,” she kept repeating to herself, greeting the teachers absently—”five thousand dollars.” And then on the porch she was suddenly aware of the awaiting boy. She eyed him critically: black, fifteen, country-bred, strong, clear-eyed.

“Well?” she asked in that brusque manner wherewith her natural timidity was wont to mask her kindness. “Well, sir?”

“I’ve come to school.”

“Humph—we can’t teach boys for nothing.”

The boy straightened. “I can pay my way,” he returned.

“You mean you can pay what we ask?”

“Why, yes. Ain’t that all?”

“No. The rest is gathered from the crumbs of Dives’ table.”

Then he saw the twinkle in her eyes. She laid her hand gently upon his shoulder.

“If you don’t hurry you’ll be late to breakfast,” she said with an air of confidence. “See those boys over there? Follow them, and at noon come to the office—wait! What’s your name?”

“Blessed Alwyn,” he answered, and the passing teachers smiled.

CHAPTER THREE: MISS MARY TAYLOR

..................

MISS MARY TAYLOR DID NOT take a college course for the purpose of teaching Negroes. Not that she objected to Negroes as human beings—quite the contrary. In the debate between the senior societies her defence of the Fifteenth Amendment had been not only a notable bit of reasoning, but delivered with real enthusiasm. Nevertheless, when the end of the summer came and the only opening facing her was the teaching of children at Miss Smith’s experiment in the Alabama swamps, it must be frankly confessed that Miss Taylor was disappointed.

Her dream had been a post-graduate course at Bryn Mawr; but that was out of the question until money was earned. She had pictured herself earning this by teaching one or two of her “specialties” in some private school near New York or Boston, or even in a Western college. The South she had not thought of seriously; and yet, knowing of its delightful hospitality and mild climate, she was not averse to Charleston or New Orleans. But from the offer that came to teach Negroes—country Negroes, and little ones at that—she shrank, and, indeed, probably would have refused it out of hand had it not been for her queer brother, John. John Taylor, who had supported her through college, was interested in cotton. Having certain schemes in mind, he had been struck by the fact that the Smith School was in the midst of the Alabama cotton-belt.

“Better go,” he had counselled, sententiously. “Might learn something useful down there.”

She had been not a little dismayed by the outlook, and had protested against his blunt insistence.

“But, John, there’s no society—just elementary work—”

John had met this objection with, “Humph!” as he left for his office. Next day he had returned to the subject.

“Been looking up Tooms County. Find some Cresswells there—big plantations—rated at two hundred and fifty thousand dollars. Some others, too; big cotton county.”

“You ought to know, John, if I teach Negroes I’ll scarcely see much of people in my own class.”

“Nonsense! Butt in. Show off. Give ‘em your Greek—and study Cotton. At any rate, I say go.”

And so, howsoever reluctantly, she had gone.

The trial was all she had anticipated, and possibly a bit more. She was a pretty young woman of twenty-three, fair and rather daintily moulded. In favorable surroundings, she would have been an aristocrat and an epicure. Here she was teaching dirty children, and the smell of confused odors and bodily perspiration was to her at times unbearable.

Then there was the fact of their color: it was a fact so insistent, so fatal she almost said at times, that she could not escape it. Theoretically she had always treated it with disdainful ease.

“What’s the mere color of a human soul’s skin,” she had cried to a Wellesley audience and the audience had applauded with enthusiasm. But here in Alabama, brought closely and intimately in touch with these dark skinned children, their color struck her at first with a sort of terror—it seemed ominous and forbidding. She found herself shrinking away and gripping herself lest they should perceive. She could not help but think that in most other things they were as different from her as in color. She groped for new ways to teach colored brains and marshal colored thoughts and the result was puzzling both to teacher and student. With the other teachers she had little commerce. They were in no sense her sort of folk. Miss Smith represented the older New England of her parents—honest, inscrutable, determined, with a conscience which she worshipped, and utterly unselfish. She appealed to Miss Taylor’s ruddier and daintier vision but dimly and distantly as some memory of the past. The other teachers were indistinct personalities, always very busy and very tired, and talking “school-room” with their meals. Miss Taylor was soon starving for human companionship, for the lighter touches of life and some of its warmth and laughter. She wanted a glance of the new books and periodicals and talk of great philanthropies and reforms. She felt out of the world, shut in and mentally anæmic; great as the “Negro Problem” might be as a world problem, it looked sordid and small at close range. So for the hundredth time she was thinking today, as she walked alone up the lane back of the barn, and then slowly down through the bottoms. She paused a moment and nodded to the two boys at work in a young cotton field.

“Cotton!”

She paused. She remembered with what interest she had always read of this little thread of the world. She had almost forgotten that it was here within touch and sight. For a moment something of the vision of Cotton was mirrored in her mind. The glimmering sea of delicate leaves whispered and murmured before her, stretching away to the Northward. She remembered that beyond this little world it stretched on and on—how far she did not know—but on and on in a great trembling sea, and the foam of its mighty waters would one time flood the ends of the earth.

She glimpsed all this with parted lips, and then sighed impatiently. There might be a bit of poetry here and there, but most of this place was such desperate prose.

She glanced absently at the boys.

One was Bles Alwyn, a tall black lad. (Bles, she mused,—now who would think of naming a boy “Blessed,” save these incomprehensible creatures!) Her regard shifted to the green stalks and leaves again, and she started to move away. Then her New England conscience stepped in. She ought not to pass these students without a word of encouragement or instruction.

“Cotton is a wonderful thing, is it not, boys?” she said rather primly. The boys touched their hats and murmured something indistinctly. Miss Taylor did not know much about cotton, but at least one more remark seemed called for.

“How long before the stalks will be ready to cut?” she asked carelessly. The farther boy coughed and Bles raised his eyes and looked at her; then after a pause he answered slowly. (Oh! these people were so slow—now a New England boy would have answered and asked a half-dozen questions in the time.)

“I—I don’t know,” he faltered.

“Don’t know! Well, of all things!” inwardly commented Miss Taylor—”literally born in cotton, and—Oh, well,” as much as to ask, “What’s the use?” She turned again to go.

“What is planted over there?” she asked, although she really didn’t care.

“Goobers,” answered the smaller boy.

“Goobers?” uncomprehendingly.

“Peanuts,” Bles specified.

“Oh!” murmured Miss Taylor. “I see there are none on the vines yet. I suppose, though, it’s too early for them.”

Then came the explosion. The smaller boy just snorted with irrepressible laughter and bolted across the fields. And Bles—was Miss Taylor deceived?—or was he chuckling? She reddened, drew herself up, and then, dropping her primness, rippled with laughter.

“What is the matter, Bles?” she asked.

He looked at her with twinkling eyes.

“Well, you see, Miss Taylor, it’s like this: farming don’t seem to be your specialty.”

The word was often on Miss Taylor’s lips, and she recognized it. Despite herself she smiled again.

“Of course, it isn’t—I don’t know anything about farming. But what did I say so funny?”

Bles was now laughing outright.

“Why, Miss Taylor! I declare! Goobers don’t grow on the tops of vines, but underground on the roots—like yams.”

“Is that so?”

“Yes, and we—we don’t pick cotton stalks except for kindling.”

“I must have been thinking of hemp. But tell me more about cotton.”

His eyes lighted, for cotton was to him a very real and beautiful thing, and a life-long companion, yet not one whose friendship had been coarsened and killed by heavy toil. He leaned against his hoe and talked half dreamily—where had he learned so well that dream-talk?

“We turn up the earth and sow it soon after Christmas. Then pretty soon there comes a sort of greenness on the black land and it swells and grows and, and—shivers. Then stalks shoot up with three or four leaves. That’s the way it is now, see? After that we chop out the weak stalks, and the strong ones grow tall and dark, till I think it must be like the ocean—all green and billowy; then come little flecks here and there and the sea is all filled with flowers—flowers like little bells, blue and purple and white.”

“Ah! that must be beautiful,” sighed Miss Taylor, wistfully, sinking to the ground and clasping her hands about her knees.

“Yes, ma’am. But it’s prettiest when the bolls come and swell and burst, and the cotton covers the field like foam, all misty—”

She bent wondering over the pale plants. The poetry of the thing began to sing within her, awakening her unpoetic imagination, and she murmured:

“The Golden Fleece—it’s the Silver Fleece!”

He harkened.

“What’s that?” he asked.

“Have you never heard of the Golden Fleece, Bles?”

“No, ma’am,” he said eagerly; then glancing up toward the Cresswell fields, he saw two white men watching them. He grasped his hoe and started briskly to work.

“Some time you’ll tell me, please, won’t you?”

She glanced at her watch in surprise and arose hastily.

“Yes, with pleasure,” she said moving away—at first very fast, and then more and more slowly up the lane, with a puzzled look on her face.

She began to realize that in this pleasant little chat the fact of the boy’s color had quite escaped her; and what especially puzzled her was that this had not happened before. She had been here four months, and yet every moment up to now she seemed to have been vividly, almost painfully conscious, that she was a white woman talking to black folk. Now, for one little half-hour she had been a woman talking to a boy—no, not even that: she had been talking—just talking; there were no persons in the conversation, just things—one thing: Cotton.

She started thinking of cotton—but at once she pulled herself back to the other aspect. Always before she had been veiled from these folk: who had put the veil there? Had she herself hung it before her soul, or had they hidden timidly behind its other side? Or was it simply a brute fact, regardless of both of them?

The longer she thought, the more bewildered she grew. There seemed no analogy that she knew. Here was a unique thing, and she climbed to her bedroom and stared at the stars.

CHAPTER FOUR: TOWN

..................

JOHN TAYLOR HAD WRITTEN TO his sister. He wanted information, very definite information, about Tooms County cotton; about its stores, its people—especially its people. He propounded a dozen questions, sharp, searching questions, and he wanted the answers tomorrow. Impossible! thought Miss Taylor. He had calculated on her getting this letter yesterday, forgetting that their mail was fetched once a day from the town, four miles away. Then, too, she did not know all these matters and knew no one who did. Did John think she had nothing else to do? And sighing at the thought of to-morrow’s drudgery, she determined to consult Miss Smith in the morning.

Miss Smith suggested a drive to town—Bles could take her in the top-buggy after school—and she could consult some of the merchants and business men. She could then write her letter and mail it there; it would be but a day or so late getting to New York.

“Of course,” said Miss Smith drily, slowly folding her napkin, “of course, the only people here are the Cresswells.”

“Oh, yes,” said Miss Taylor invitingly. There was an allurement about this all-pervasive name; it held her by a growing fascination and she was anxious for the older woman to amplify. Miss Smith, however, remained provokingly silent, so Miss Taylor essayed further.

“What sort of people are the Cresswells?” she asked.

“The old man’s a fool; the young one a rascal; the girl a ninny,” was Miss Smith’s succinct and acid classification of the county’s first family; adding, as she rose, “but they own us body and soul.” She hurried out of the dining-room without further remark. Miss Smith was more patient with black folk than with white.

The sun was hanging just above the tallest trees of the swamp when Miss Taylor, weary with the day’s work, climbed into the buggy beside Bles. They wheeled comfortably down the road, leaving the sombre swamp, with its black-green, to the right, and heading toward the golden-green of waving cotton fields. Miss Taylor lay back, listlessly, and drank the soft warm air of the languorous Spring. She thought of the golden sheen of the cotton, and the cold March winds of New England; of her brother who apparently noted nothing of leaves and winds and seasons; and of the mighty Cresswells whom Miss Smith so evidently disliked. Suddenly she became aware of her long silence and the silence of the boy.

“Bles,” she began didactically, “where are you from?”

He glanced across at her and answered shortly:

“Georgia, ma’am,” and was silent.

The girl tried again.

“Georgia is a large State,”—tentatively.

“Yes, ma’am.”

“Are you going back there when you finish?”

“I don’t know.”

“I think you ought to—and work for your people.”

“Yes, ma’am.”

She stopped, puzzled, and looked about. The old horse jogged lazily on, and Bles switched him unavailingly. Somehow she had missed the way today. The Veil hung thick, sombre, impenetrable. Well, she had done her duty, and slowly she nestled back and watched the far-off green and golden radiance of the cotton.

“Bles,” she said impulsively, “shall I tell you of the Golden Fleece?”

He glanced at her again.

“Yes’m, please,” he said.

She settled herself almost luxuriously, and began the story of Jason and the Argonauts.

The boy remained silent. And when she had finished, he still sat silent, elbow on knee, absently flicking the jogging horse and staring ahead at the horizon. She looked at him doubtfully with some disappointment that his hearing had apparently shared so little of the joy of her telling; and, too, there was mingled a vague sense of having lowered herself to too familiar fellowship with this—this boy. She straightened herself instinctively and thought of some remark that would restore proper relations. She had not found it before he said, slowly:

“All yon is Jason’s.”

“What?” she asked, puzzled.

He pointed with one sweep of his long arm to the quivering mass of green-gold foliage that swept from swamp to horizon.

“All yon golden fleece is Jason’s now,” he repeated.

“I thought it was—Cresswell’s,” she said.

“That’s what I mean.”

She suddenly understood that the story had sunk deeply.

“I am glad to hear you say that,” she said methodically, “for Jason was a brave adventurer—”

“I thought he was a thief.”

“Oh, well—those were other times.”

“The Cresswells are thieves now.”

Miss Taylor answered sharply.

“Bles, I am ashamed to hear you talk so of your neighbors simply because they are white.”

But Bles continued.

“This is the Black Sea,” he said, pointing to the dull cabins that crouched here and there upon the earth, with the dark twinkling of their black folk darting out to see the strangers ride by.

Despite herself Miss Taylor caught the allegory and half whispered, “Lo! the King himself!” as a black man almost rose from the tangled earth at their side. He was tall and thin and sombre-hued, with a carven face and thick gray hair.

“Your servant, mistress,” he said, with a sweeping bow as he strode toward the swamp. Miss Taylor stopped him, for he looked interesting, and might answer some of her brother’s questions. He turned back and stood regarding her with sorrowful eyes and ugly mouth.

“Do you live about here?” she asked.

“I’se lived here a hundred years,” he answered. She did not believe it; he might be seventy, eighty, or even ninety—indeed, there was about him that indefinable sense of age—some shadow of endless living; but a hundred seemed absurd.

“You know the people pretty well, then?”

“I knows dem all. I knows most of ‘em better dan dey knows demselves. I knows a heap of tings in dis world and in de next.”

“This is a great cotton country?”

“Dey don’t raise no cotton now to what dey used to when old Gen’rel Cresswell fust come from Carolina; den it was a bale and a half to the acre on stalks dat looked like young brushwood. Dat was cotton.”

“You know the Cresswells, then?”

“Know dem? I knowed dem afore dey was born.”

“They are—wealthy people?”

“Dey rolls in money and dey’se quality, too. No shoddy upstarts dem, but born to purple, lady, born to purple. Old Gen’ral Cresswell had niggers and acres no end back dere in Carolina. He brung a part of dem here and here his son, de father of dis Colonel Cresswell, was born. De son—I knowed him well—he had a tousand niggers and ten tousand acres afore de war.”

“Were they kind to their slaves?”

“Oh, yaas, yaas, ma’am, dey was careful of de’re niggers and wouldn’t let de drivers whip ‘em much.”

“And these Cresswells today?”

“Oh, dey’re quality—high-blooded folks—dey’se lost some land and niggers, but, lordy, nuttin’ can buy de Cresswells, dey naturally owns de world.”

“Are they honest and kind?”

“Oh, yaas, ma’am—dey’se good white folks.”

“Good white folk?”

“Oh, yaas, ma’am—course you knows white folks will be white folks—white folks will be white folks. Your servant, ma’am.” And the swamp swallowed him.

The boy’s eyes followed him as he whipped up the horse.

“He’s going to Elspeth’s,” he said.

“Who is he?”

“We just call him Old Pappy—he’s a preacher, and some folks say a conjure man, too.”

“And who is Elspeth?”

“She lives in the swamp—she’s a kind of witch, I reckon, like—like—”

“Like Medea?”

“Yes—only—I don’t know—” and he grew thoughtful.

The road turned now and far away to the eastward rose the first straggling cabins of the town. Creeping toward them down the road rolled a dark squat figure. It grew and spread slowly on the horizon until it became a fat old black woman, hooded and aproned, with great round hips and massive bosom. Her face was heavy and homely until she looked up and lifted the drooping cheeks, and then kindly old eyes beamed on the young teacher, as she curtsied and cried:

“Good-evening, honey! Good-evening! You sure is pretty dis evening.”

“Why, Aunt Rachel, how are you?” There was genuine pleasure in the girl’s tone.

“Just tolerable, honey, bless de Lord! Rumatiz is kind o’ bad and Aunt Rachel ain’t so young as she use ter be.”

“And what brings you to town afoot this time of day?”

The face fell again to dull care and the old eyes crept away. She fumbled with her cane.

“It’s de boys again, honey,” she returned solemnly; “dey’se good boys, dey is good to de’re old mammy, but dey’se high strung and dey gits fighting and drinking and—and—last Saturday night dey got took up again. I’se been to Jedge Grey—I use to tote him on my knee, honey—I’se been to him to plead him not to let ‘em go on de gang, ‘cause you see, honey,” and she stroked the girl’s sleeve as if pleading with her, too, “you see it done ruins boys to put ‘em on de gang.”

Miss Taylor tried hard to think of something comforting to say, but words seemed inadequate to cheer the old soul; but after a few moments they rode on, leaving the kind face again beaming and dimpling.

And now the country town of Toomsville lifted itself above the cotton and corn, fringed with dirty straggling cabins of black folk. The road swung past the iron watering trough, turned sharply and, after passing two or three pert cottages and a stately house, old and faded, opened into the wide square. Here pulsed the very life and being of the land. Yonder great bales of cotton, yellow-white in its soiled sacking, piled in lofty, dusty mountains, lay listening for the train that, twice a day, ran out to the greater world. Round about, tied to the well-gnawed hitching rails, were rows of mules—mules with back cloths; mules with saddles; mules hitched to long wagons, buggies, and rickety gigs; mules munching golden ears of corn, and mules drooping their heads in sorrowful memory of better days.

Beyond the cotton warehouse smoked the chimneys of the seed-mill and the cotton-gin; a red livery-stable faced them and all about three sides of the square ran stores; big stores and small wide-windowed, narrow stores. Some had old steps above the worn clay side-walks, and some were flush with the ground. All had a general sense of dilapidation—save one, the largest and most imposing, a three-story brick. This was Caldwell’s “Emporium”; and here Bles stopped and Miss Taylor entered.

Mr. Caldwell himself hurried forward; and the whole store, clerks and customers, stood at attention, for Miss Taylor was yet new to the county.

She bought a few trifles and then approached her main business.

“My brother wants some information about the county, Mr. Caldwell, and I am only a teacher, and do not know much about conditions here.”

“Ah! where do you teach?” asked Mr. Caldwell. He was certain he knew the teachers of all the white schools in the county. Miss Taylor told him. He stiffened slightly but perceptibly, like a man clicking the buckles of his ready armor, and two townswomen who listened gradually turned their backs, but remained near.

“Yes—yes,” he said, with uncomfortable haste. “Any—er—information—of course—” Miss Taylor got out her notes.

“The leading land-owners,” she began, sorting the notes searchingly, “I should like to know something about them.”

“Well, Colonel Cresswell is, of course, our greatest landlord—a high-bred gentleman of the old school. He and his son—a worthy successor to the name—hold some fifty thousand acres. They may be considered representative types. Then, Mr. Maxwell has ten thousand acres and Mr. Tolliver a thousand.”

Miss Taylor wrote rapidly. “And cotton?” she asked.

“We raise considerable cotton, but not nearly what we ought to; nigger labor is too worthless.”

“Oh! The Negroes are not, then, very efficient?”

“Efficient!” snorted Mr. Caldwell; at last she had broached a phase of the problem upon which he could dilate with fervor. “They’re the lowest-down, ornriest—begging your pardon—good-for-nothing loafers you ever heard of. Why, we just have to carry them and care for them like children. Look yonder,” he pointed across the square to the court-house. It was an old square brick-and-stucco building, sombre and stilted and very dirty. Out of it filed a stream of men—some black and shackled; some white and swaggering and liberal with tobacco-juice; some white and shaven and stiff. “Court’s just out,” pursued Mr. Caldwell, “and them niggers have just been sent to the gang—young ones, too; educated but good for nothing. They’re all that way.”

Miss Taylor looked up a little puzzled, and became aware of a battery of eyes and ears. Everybody seemed craning and listening, and she felt a sudden embarrassment and a sense of half-veiled hostility in the air. With one or two further perfunctory questions, and a hasty expression of thanks, she escaped into the air.

The whole square seemed loafing and lolling—the white world perched on stoops and chairs, in doorways and windows; the black world filtering down from doorways to side-walk and curb. The hot, dusty quadrangle stretched in dreary deadness toward the temple of the town, as if doing obeisance to the court-house. Down the courthouse steps the sheriff, with Winchester on shoulder, was bringing the last prisoner—a curly-headed boy with golden face and big brown frightened eyes.

“It’s one of Dunn’s boys,” said Bles. “He’s drunk again, and they say he’s been stealing. I expect he was hungry.” And they wheeled out of the square.

Miss Taylor was tired, and the hastily scribbled letter which she dropped into the post in passing was not as clearly expressed as she could wish.

A great-voiced giant, brown and bearded, drove past them, roaring a hymn. He greeted Bles with a comprehensive wave of the hand.

“I guess Tylor has been paid off,” said Bles, but Miss Taylor was too disgusted to answer. Further on they overtook a tall young yellow boy walking awkwardly beside a handsome, bold-faced girl. Two white men came riding by. One leered at the girl, and she laughed back, while the yellow boy strode sullenly ahead. As the two white riders approached the buggy one said to the other:

“Who’s that nigger with?”

“One of them nigger teachers.”

“Well, they’ll stop this damn riding around or they’ll hear something,” and they rode slowly by.

Miss Taylor felt rather than heard their words, and she was uncomfortable. The sun fell fast; the long shadows of the swamp swept soft coolness on the red road. Then afar in front a curled cloud of white dust arose and out of it came the sound of galloping horses.

“Who’s this?” asked Miss Taylor.

“The Cresswells, I think; they usually ride to town about this time.” But already Miss Taylor had descried the brown and tawny sides of the speeding horses.

“Good gracious!” she thought. “The Cresswells!” And with it came a sudden desire not to meet them—just then. She glanced toward the swamp. The sun was sifting blood-red lances through the trees. A little wagon-road entered the wood and disappeared. Miss Taylor saw it.

“Let’s see the sunset in the swamp,” she said suddenly. On came the galloping horses. Bles looked up in surprise, then silently turned into the swamp. The horses flew by, their hoof-beats dying in the distance. A dark green silence lay about them lit by mighty crimson glories beyond. Miss Taylor leaned back and watched it dreamily till a sense of oppression grew on her. The sun was sinking fast.

“Where does this road come out?” she asked at last.

“It doesn’t come out.”

“Where does it go?”

“It goes to Elspeth’s.”

“Why, we must turn back immediately. I thought—” But Bles was already turning. They were approaching the main road again when there came a fluttering as of a great bird beating its wings amid the forest. Then a girl, lithe, dark brown, and tall, leaped lightly into the path with greetings on her lips for Bles. At the sight of the lady she drew suddenly back and stood motionless regarding Miss Taylor, searching her with wide black liquid eyes. Miss Taylor was a little startled.

“Good—good-evening,” she said, straightening herself.

The girl was still silent and the horse stopped. One tense moment pulsed through all the swamp. Then the girl, still motionless—still looking Miss Taylor through and through—said with slow deliberateness:

“I hates you.”

The teacher in Miss Taylor strove to rebuke this unconventional greeting but the woman in her spoke first and asked almost before she knew it—

“Why?”

CHAPTER FIVE: ZORA

..................

ZORA, CHILD OF THE SWAMP, was a heathen hoyden of twelve wayward, untrained years. Slight, straight, strong, full-blooded, she had dreamed her life away in wilful wandering through her dark and sombre kingdom until she was one with it in all its moods; mischievous, secretive, brooding; full of great and awful visions, steeped body and soul in wood-lore. Her home was out of doors, the cabin of Elspeth her port of call for talking and eating. She had not known, she had scarcely seen, a child of her own age until Bles Alwyn had fled from her dancing in the night, and she had searched and found him sleeping in the misty morning light. It was to her a strange new thing to see a fellow of like years with herself, and she gripped him to her soul in wild interest and new curiosity. Yet this childish friendship was so new and incomprehensible a thing to her that she did not know how to express it. At first she pounced upon him in mirthful, almost impish glee, teasing and mocking and half scaring him, despite his fifteen years of young manhood.

“Yes, they is devils down yonder behind the swamp,” she would whisper, warningly, when, after the first meeting, he had crept back again and again, half fascinated, half amused to greet her; “I’se seen ‘em, I’se heard ‘em, ‘cause my mammy is a witch.”

The boy would sit and watch her wonderingly as she lay curled along the low branch of the mighty oak, clinging with little curved limbs and flying fingers. Possessed by the spirit of her vision, she would chant, low-voiced, tremulous, mischievous:

“One night a devil come to me on blue fire out of a big red flower that grows in the south swamp; he was tall and big and strong as anything, and when he spoke the trees shook and the stars fell. Even mammy was afeared; and it takes a lot to make mammy afeared, ‘cause she’s a witch and can conjure. He said, ‘I’ll come when you die—I’ll come when you die, and take the conjure off you,’ and then he went away on a big fire.”

“Shucks!” the boy would say, trying to express scornful disbelief when, in truth, he was awed and doubtful. Always he would glance involuntarily back along the path behind him. Then her low birdlike laughter would rise and ring through the trees.

So passed a year, and there came the time when her wayward teasing and the almost painful thrill of her tale-telling nettled him and drove him away. For long months he did not meet her, until one day he saw her deep eyes fixed longingly upon him from a thicket in the swamp. He went and greeted her. But she said no word, sitting nested among the greenwood with passionate, proud silence, until he had sued long for peace; then in sudden new friendship she had taken his hand and led him through the swamp, showing him all the beauty of her swamp-world—great shadowy oaks and limpid pools, lone, naked trees and sweet flowers; the whispering and flitting of wild things, and the winging of furtive birds. She had dropped the impish mischief of her way, and up from beneath it rose a wistful, visionary tenderness; a mighty half-confessed, half-concealed, striving for unknown things. He seemed to have found a new friend.

And today, after he had taken Miss Taylor home and supped, he came out in the twilight under the new moon and whistled the tremulous note that always brought her.

“Why did you speak so to Miss Taylor?” he asked, reproachfully. She considered the matter a moment.

“You don’t understand,” she said. “You can’t never understand. I can see right through people. You can’t. You never had a witch for a mammy—did you?”

“No.”

“Well, then, you see I have to take care of you and see things for you.”

“Zora,” he said thoughtfully, “you must learn to read.”

“What for?”

“So that you can read books and know lots of things.”

“Don’t white folks make books?”

“Yes—most of the books.”

“Pooh! I knows more than they do now—a heap more.”

“In some ways you do; but they know things that give them power and wealth and make them rule.”

“No, no. They don’t really rule; they just thinks they rule. They just got things—heavy, dead things. We black folks is got the spirit. We’se lighter and cunninger; we fly right through them; we go and come again just as we wants to. Black folks is wonderful.”

He did not understand what she meant; but he knew what he wanted and he tried again.

“Even if white folks don’t know everything they know different things from us, and we ought to know what they know.”

This appealed to her somewhat.

“I don’t believe they know much,” she concluded; “but I’ll learn to read and just see.”

“It will be hard work,” he warned. But he had come prepared for acquiescence. He took a primer from his pocket and, lighting a match, showed her the alphabet.

“Learn those,” he said.

“What for?” she asked, looking at the letters disdainfully.

“Because that’s the way,” he said, as the light flared and went out.

“I don’t believe it,” she disputed, disappearing in the wood and returning with a pine-knot. They lighted it and its smoky flame threw wavering shadows about. She turned the leaves till she came to a picture which she studied intently.

“Is this about this?” she asked, pointing alternately to reading and picture.

“Yes. And if you learn—”

“Read it,” she commanded. He read the page.

“Again,” she said, making him point out each word. Then she read it after him, accurately, with more perfect expression. He stared at her. She took the book, and with a nod was gone.

It was Saturday and dark. She never asked Bles to her home—to that mysterious black cabin in mid-swamp. He thought her ashamed of it, and delicately refrained from going. So tonight she slipped away, stopped and listened till she heard his footsteps on the pike, and then flew homeward. Presently the old black cabin loomed before her with its wide flapping door. The old woman was bending over the fire, stirring some savory mess, and a yellow girl with a white baby on one arm was placing dishes on a rickety wooden table when Zora suddenly and noiselessly entered the door.

“Come, is you? I ‘lowed victuals would fetch you,” grumbled the hag.

But Zora deigned no answer. She walked placidly to the table, where she took up a handful of cold corn-bread and meat, and then went over and curled up by the fire.

Elspeth and the girl talked and laughed coarsely, and the night wore on.

By and by loud laughter and tramping came from the road—a sound of numerous footsteps. Zora listened, leapt to her feet and started to the door. The old crone threw an epithet after her; but she flashed through the lighted doorway and was gone, followed by the oath and shouts from the approaching men. In the hut night fled with wild song and revel, and day dawned again. Out from some fastness of the wood crept Zora. She stopped and bathed in a pool, and combed her close-clung hair, then entered silently to breakfast.

Thus began in the dark swamp that primal battle with the Word. She hated it and despised it, but her pride was in arms and her one great life friendship in the balance. She fought her way with a dogged persistence that brought word after word of praise and interest from Bles. Then, once well begun, her busy, eager mind flew with a rapidity that startled; the stories especially she devoured—tales of strange things and countries and men gripped her imagination and clung to her memory.

“Didn’t I tell you there was lots to learn?” he asked once.

“I knew it all,” she retorted; “every bit. I’se thought it all before; only the little things is different—and I like the little, strange things.”

Spring ripened to summer. She was reading well and writing some.

“Zora,” he announced one morning under their forest oak, “you must go to school.”

She eyed him, surprised.

“Why?”

“You’ve found some things worth knowing in this world, haven’t you, Zora?”

“Yes,” she admitted.

“But there are more—many, many more—worlds on worlds of things—you have not dreamed of.”

She stared at him, open-eyed, and a wonder crept upon her face battling with the old assurance. Then she looked down at her bare brown feet and torn gown.

“I’ve got a little money, Zora,” he said quickly.

But she lifted her head.

“I’ll earn mine,” she said.

“How?” he asked doubtfully.

“I’ll pick cotton.”

“Can you?”

“Course I can.”

“It’s hard work.”

She hesitated.

“I don’t like to work,” she mused. “You see, mammy’s pappy was a king’s son, and kings don’t work. I don’t work; mostly I dreams. But I can work, and I will—for the wonder things—and for you.”

So the summer yellowed and silvered into fall. All the vacation days Bles worked on the farm, and Zora read and dreamed and studied in the wood, until the land lay white with harvest. Then, without warning, she appeared in the cotton-field beside Bles, and picked.