Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

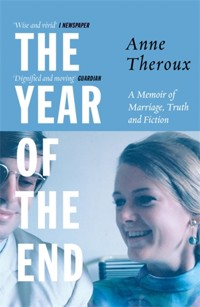

'A moving and absorbing account' Adam Buxton 'Scorching ... a brave book' Helen Brown, Telegraph 'A wise and vivid memoir of a disintegrating marriage and a study of the role of the spouse in the life of a literary giant' Fiona Sturges, i Paper 18TH JANUARY 1990 Paul left today at 8am. We had been married just over 22 years. The previous evening we had gone out to eat at a local restaurant, where we drank champagne and reminisced. In a short story which he wrote about that final evening of a marriage, the central characters talk wittily and poignantly about the explorer Sir Richard Burton and the sad, misunderstood wife who burnt his books. The reality was different. 'This memoir is based on the diary I kept during 1990, the year that my first marriage came to an end.' After 22 years, spent across four continents, with two children - Louis and Marcel - in 1990 Anne and Paul Theroux decided to separate. For that year, Anne - later a professional relationship therapist herself - kept a diary, noting not only her day-to-day experiences as a busy freelance journalist and broadcaster, but the contrasts in her feelings between despairing grief and hope for a new future. With reflections on truth and fiction, literature and art, and the nature of marriage, alongside commentary on notable political and cultural events, and interviews with prominent writers of the time, including Kingsley Amis and Barbara Cartland, The Year of the End offers a unique insight into the unravelling of a relationship and the attempt to rebuild a life.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 300

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE YEAR OF THE END

A Memoir

Anne Theroux

for Marcel and Louis

Truth becomes fiction when the fiction’s true; Real becomes not-real when the unreal’s real.

Dream of the Red Chamber Cao Xueqin

This memoir is based on the diary I kept during 1990, the year that my first marriage came to an end. Some time after that, in the late nineties, I used the diary to trigger thoughts and recollections which I wrote down while the events of that year were still fresh in my mind. I was trying to write truth, not fiction.

Actual diary entries and quotations from written sources have been reproduced without alteration, though they may have been shortened. Many of the interviews (with Barbara Cartland, Kingsley Amis and Elisabeth Frink, for example) were transcribed from my cassette recordings. Other conversations are from memory. Names of some minor characters have been changed.

Contents

Chapter 1

Once upon a time …

Once upon a time in a warm December, when I was teaching at a school near Mount Kenya and wondering whether I should pack my bags and drive to Uganda to get married, I bought a diary for the year ahead. Inside the cover was a green, sticky-backed label made up of perforated strips, to be inserted in the diary, ready-printed with these reminders:

Tomorrow is my father’s birthday

Tomorrow is my mother’s birthday

Tomorrow is my wedding anniversary

Tomorrow is …

Tomorrow is …

When my fiancé came to visit me, wearing a dusty suit, open-necked shirt and plimsolls, having driven 500 miles from Kampala in a day, on a road that was still not completely tarmacked, he seized the diary and the green labels with delight.

‘It’s a poem by T.S. Eliot,’ he said, reading it aloud in a lugubrious voice.

I don’t remember sticking the strips into the diary. It was for the year 1968, the year of les événements in Paris and the Battle of Grosvenor Square in London, the year of the Tet Offensive, the Biafran War, the Soviet invasion of Prague, the murder of Martin Luther King and the year my first son was born in Mulago Hospital, Kampala on 13th June. None of these could have been marked in advance with a green sticker. And I no longer have that diary. However, I do have a diary for another, much later year, which often opens at this page:

18th January 1990

Paul left today at 8am.

We had been married just over 22 years.

The previous evening we had gone out to eat at a local restaurant, where we drank champagne and reminisced. In a short story which he wrote about that final evening of a marriage, the central characters talk wittily and poignantly about the explorer Sir Richard Burton and the sad, misunderstood wife who burnt his books.* The reality was different: we talked about the au pair girls who had cared for our sons while I went out to work and he wrote, and the amahs who had done the same job in Singapore. (In Africa they are called ayahs, but since we left Uganda when our first son was only four months old, we never employed one.) The conversation chronicled the years.

In 1968, a violent incident in Kampala prompted Paul to resign from his job at Makerere University and make plans to leave Africa. The poet D.J. Enright, Professor of English at Singapore University, was an admirer of my husband’s writing and offered him a post as a lecturer. Just before we were due to leave Uganda, the Vice Chancellor, a top man in Singapore’s ruling party, discovered that some of this writing might be considered seditious and tried to get the appointment blocked. Dennis Enright threatened to resign. We waited nervously in Kampala; we had no money and nowhere else to go. A compromise was reached: Paul was offered a job on the lowest possible salary and on condition he promised not to write about Singapore politics. He accepted. We lived in Singapore from 1968 until 1971.

During most of the Singapore years I taught English too, at Nanyang, the Chinese language university, where the students had Chinese names, wore conservative clothes, and were more likely (I suspected) secretly to sympathise with Mao Zedong and the Cultural Revolution than their English-educated counterparts with whom Paul studied the plays of Shakespeare and his contemporaries, and who had names like Annabel Chan and Reggie Chew. To enable us both to do our jobs, we shared our small house off Bukit Timah Road first with Ah Ho, a soft-faced Cantonese girl who left when she had a child of her own, and then with Susan, a svelte Hakka in black stretch-pants. On one very special occasion Susan came out of her room ready for the weekend in a short skirt. ‘You got legs!’ remarked Marcel, who at eighteen months had the glottal stops of the Singapore Chinese. When Louis was born in 1970, a careworn woman, whose very name, Ai Yah, was like a cry of despair, was recruited as additional help.

I suppose I wouldn’t recognise them now. We said goodbye to Singapore in November 1971, taking a final picture of Susan and Ai Yah holding the children, and flew to England. After a brief attempt at rural domesticity in Dorset, we moved to London.

In 1972, when Paul was writing Saint Jack, his revenge on the Singapore authorities, and I started work for the BBC, a north-country lass called Beryl moved into our terraced house in Catford; she was a latter-day Beatles fan but also liked the Bay City Rollers, the Jackson 5 and The Osmonds; Marcel and Louis, aged four and two, appreciated her taste in music and the house rang with shrill voices singing ‘I’ll be your long-haired lover from Liverpool’. Beryl was a good companion when my husband left on his first long absence – a term teaching at the university of Virginia. I had ordered a carpet for the hall. When it was laid, the living room door wouldn’t open. Beryl helped me remove the door from its hinges and held it while I sawed half an inch off the bottom. A few weeks later she comforted me when I cried because rain had leaked through the roof and stained the new carpet. I was crying because I found it hard to do my job and run the household without my husband, because I was ashamed of my own weakness and because our home, the first we had owned, was flawed. I wanted it to be perfect.

At Christmas I flew with the children to Virginia to be reunited with Paul. He confessed to an affair with a student, the first admitted infidelity, and I kissed him and said it didn’t matter, thinking this was true. We came back to London with a record player for Beryl, but the goodwill was marred when we found evidence of an unruly party held in our living room the previous night. Shortly afterwards Beryl left and her place was taken by a Norwegian girl called Inge, who broke the hearts of several local youths and seduced my young brother-in-law when he came to stay.

Inge was still with us when Paul went off on The Great Railway Bazaar journey, which was the beginning of his success as a writer. It was my turn to be unfaithful, and Inge shopped me when he returned. I had confessed myself, but she added further incriminating details. We span into a turmoil of misery and rage which Paul described much later in his novel, My Secret History. Miraculously we emerged, not unscathed but ready to resume a fairly happy family life. Inge was succeeded by a Welsh girl called Liz who became pregnant by a local fireman: her family made a day trip to London for the wedding. I think the next was Catherine, a lively seventeen year old who was soon part of the family. There was an Australian called Amy who ordered Louis to stand in the corner when he made a puking face at the food on his plate and a butcher’s daughter called Priscilla who entertained him by counting the planes that flew over our house. (By this time we had moved to a bigger house, in Wandsworth, and were on the flight path to Heathrow.) There was another Australian, Sue, who stayed twice, the second time with the man she married (many years later we visited them in New South Wales) and another English girl, Avril, who boiled her jeans in a saucepan used for stew and gave us all diarrhoea. And there was a German, Monika, who had a little dog called Idéfix, and who, in return for some favour which I have since forgotten, painted our bedroom purple.

In the last six or seven years there had been no au pairs, only daily cleaners: Mrs Bondy, Flora Jeffreys and Maisie Flynn. Mrs Bondy had the gift of the memorable phrase and contributed at least two to the family vocabulary: ‘They don’t have our clean ways’ (applied to anyone who lived east of Calais) and ‘Having a good pick then?’ (addressed to a child furtively fumbling with his nose). She left after a row when the central heating thermostat was mysteriously turned to max 24 hrs while we were on a skiing holiday. Flora Jeffreys left to run a canteen on a building site. Maisie Flynn died in St Thomas’ Hospital.

We talked about some, but not all of these memories over our last dinner, summoning up a procession of ghosts with mops and brooms. Back in the purple bedroom, having walked home across Wandsworth Common, we made love, as we had done a thousand times before, kissed and turned to our separate pillows. In the morning Paul called a taxi. When it arrived, he sat on the bed and hugged me and we both shed tears.

‘I’ll be back,’ he said. Then he left for ever.

My diary entry reads:

Paul left today at 8am, the beginning of a six-month separation. I spent a futile, miserable day drinking, smoking a joint (I even burnt the carpet) and hoping I can pull myself together tomorrow.

Tomorrow is …

* ‘Champagne’ in My Other Life, by Paul Theroux, 1996.

Chapter 2

August 1989

August 1989 was spent as usual on Cape Cod, in the house Paul had bought in 1983. It was a beautiful house set in three acres of land. The living room had windows on every side and to the north looked out on the long, curved bay, between Plymouth and Provincetown, that forms the inner crooked arm of the Cape. We were in East Sandwich, near the elbow, just a few miles from the Cape Cod Canal and a lighthouse, which glowed at night and hummed a warning. I used to listen to it as I lay in bed next to him.

Neither of our sons was with us that year. They were both in France at a summer school near Montpellier. Marcel would be joining us before the end of the month and then staying on in America: he had a scholarship to Yale to do an MA in International Relations. Louis would not be visiting the Cape this summer: after France he was joining the family of a school friend in Corfu, then returning to London briefly before going up for his second year at Oxford. Paul was moody and distracted, disappointed that our sons had chosen to be elsewhere. But I was there; couldn’t we enjoy at last some time alone together?

This year I was not going to collect material for radio programmes as I had during the last few summers. The obvious subjects in the area had been exhausted. I had made a half-hour programme about American attitudes to Ireland, commuting to Boston every day to interview Irish Americans from all points on the political spectrum and spending many hours waiting in vain for Edward Kennedy and Tip O’Neill to return my calls. I had investigated the history of the Native Wampanoag people and interviewed their medicine man, Slow Turtle, aka John Peters (‘my slave name’ he called it); I had been out on a whale-watching trip and talked to Captain ‘Stormy’ Mayo about whales and whaling. I had written to Stephen King in Maine, telling him how much I admired his books and asking for an interview; his secretary had politely refused.

This summer I would do nothing but swim in the pool, sunbathe, read and see if I could enjoy being a wife. Perhaps I would make beach plum jelly. This time-consuming and unrewarding activity epitomised for me the life of a housewife on Cape Cod. ‘What would I do? Make beach plum jelly?’ I asked, when Paul talked about living there permanently. He already spent more time in East Sandwich than I wanted, leaving London in June and not returning till September. The rest of us joined him for the month of August. It was a good place for a holiday but it was a hard place to live in properly, unless you were a professional writer like Paul, who carried his work around with him. If, like me, your well-being depended on having a job to go to, people to talk to, streets to walk through and buses to hop on, more than a month on the Cape began to feel like deprivation.

It was a good place for a holiday, for those who are good at holidays. We had different views on them. For me, being on holiday means filling each day with pleasure and taking a break from duty, preferably in the company of the people you like best. Paul never took a break from writing, perhaps because it was his greatest pleasure; only when inspiration failed him, sometimes by lunch time but often not until the light was fading at the end of the day, would he leave his desk and be ready for a walk on the beach, a visit to the cinema, a drink or a conversation. When these quotidian activities seemed inadequate, we would drive the jeep, with his rowing boat swinging dangerously on the trailer behind it, to distant points on the Cape and he would push off for several hours’ solitary rowing. I would drive the jeep back home and wait for a phone call late in the evening to let me know where I should pick him up.

Just occasionally he could be tempted to join in the kind of family outing I associate with holidays. A favourite destination for such a trip was Martha’s Vineyard, the fashionable island south of the Cape where many famous people had summer homes. We would leave early in the morning with the boys and meet up with other members of Paul’s family at the ferry in Hyannis. On board we drank coffee out of styrofoam cups and ate doughnuts, while the boat chugged across the stretch of water which separated the island from the mainland. In Vineyard Haven we rented bicycles for the day and set out along the cycle track to Edgartown, where we would look around the shops and buy sandwiches for lunch, before wheeling our bikes aboard another tiny ferry to the island of Chappaquiddick, even more remote, less populated and more exclusive. It was always hot and by this time the boys would be wearing long-sleeved shirts to protect their arms from the sun while they cycled.

A narrow road through pine trees became a sandy path and eventually we arrived at the bridge where, late one night in 1969, Senator Edward Kennedy’s car veered into the water, drowning Mary Jo Kopechne. The Senator, according to his own account, ‘dove and dove repeatedly’ to save her. We had inspected the site and formed our own conclusions about what really happened, and each year, Paul’s brother, a Washington lawyer, would make us huddle round him to hear the latest rumoured version.

‘There was another woman in the car.’ Gene mouthed the words almost silently into the summer air as we widened our eyes and gripped our handlebars. ‘Mary Jo was asleep in the back seat.’ He did his best to provide a new piece of gossip each year, though we had long ceased to believe him. This one was too implausible even to pass on at dinner parties in London.

A little further on was our favourite beach, where we would spend the middle hours of the day, swimming, talking and eating our sandwiches.

We usually started the return cycle ride just a bit later than was sensible; the children would be tired and there seemed to be more uphill stretches on the way back, so for the last mile everyone was under pressure to pedal hard, otherwise we would miss the ferry. By the time we got back to the Cape I felt sunburnt, exhausted and satisfied.

There had been variations on the trip. Once, having hired our bikes, we had set out not to Edgartown but to the Gay Head cliffs, on the other side of the island. The cliffs were made of clay with special healing properties and the area had once been inhabited by Native American whale hunters. It was a much longer ride than we had bargained for and when we got to the cliffs, about which I remember nothing, it was time to start back again, with a snatched lunch from a roadside café and no chance of even a swim. The photographs taken during that day show a happy group setting out and a very cross one returning. On another occasion, when Louis was too young to ride a bike, he sat on Paul’s crossbar and at a bumpy point on the ride got his foot caught in the spokes, bringing bike and riders crashing to the ground. We made for the nearest beach and bathed his bruised foot. It could have been worse.

But this year, the summer of 1989, Paul and I went to the Vineyard alone and for the first time rented not bicycles but a small motor scooter, which Paul drove while I rode pillion, just as we had once driven round a Pacific island off Tahiti. There was time to explore new areas; time to re-visit the Gay Head cliffs. We strolled on a beach on the far side of the island.

‘Look,’ said Paul. ‘There’s a man with no clothes on.’

I squinted into the sun and ascertained that this was so, and that further along the beach there were many naked people. We walked among them, wondering at the different shapes and sizes of men’s genitals, classifying them as tassels, bath plugs, carrots and bananas.

‘I think they’re all the same when they’re erect,’ I said.

‘How do you know?’

‘I read it in a book.’

‘I don’t believe it.’

I agreed it seemed unlikely.

Eventually we took off our clothes and swam. From the water we noticed people higher up the beach rolling in mud and smearing themselves with it. We tried it ourselves and I took a photo of Paul, naked and neanderthal, streaked with clay, which later we stuck on the fridge in the kitchen.

The only thing which marred the day was that I burnt my leg on the engine of the bike. It seemed a trivial hurt at the time, but it got worse as the holiday continued and the burn blistered and oozed.

There was something else hurting me too. That summer Paul had published a book called My Secret History, a novel, drawing on our life together, and I was wounded by it. Although there were things about the character based on me which I liked and accepted, Jenny Parent had other qualities which I hated: she was shrewish and humourless. The portrayal diminished me. I was also upset by the descriptions of Andre Parent’s affair with a woman called Eden. In real life this woman was an English teacher from Pennsylvania with whom Paul had had two affairs, one in 1982 and one in 1986. These affairs, unlike previous ones, had been serious: he considered leaving me, hesitating, sulking and making me unhappy and insecure. Both had eventually ended, after much misery, and I had learned to suppress the mad, jealous questions with which I had once bombarded him. The book, cruelly, teased me with answers which may or may not have been fictional. Had he really taken her on one of his trips to India? Had he really …?

‘It’s a novel,’ said Paul. ‘It isn’t true.’

The previous year, when I read the book in manuscript, I blue-pencilled certain passages and added phrases in other places, most of which he ignored. I wasn’t altogether surprised; some of the additions were written in facetious rage, for instance, ‘She was wearing big baggy bloomers’ in a scene where the hero undressed his lover. Now that the book had been published, and received good reviews, I had decided that the only way to deal with my discomfort was to go along with Paul’s insistence that the whole thing was a work of fiction, which of course it was, in a way. Friends would telephone and ask, ‘How did you feel about Paul’s book?’

‘I think it’s a wonderful book.’

There would be a pause. This wasn’t the answer they expected. How the conversation continued depended on the degree of their insensitivity, animosity, or nosiness.

‘But the wife is such a horrible character,’ said one old friend. ‘Not at all like you, of course.’

‘I quite like the wife. But it’s all made up. It’s a novel.’

It was hard for those friends who genuinely wanted to sympathise to say the right thing; there was no right thing to say. The book was a betrayal.

The trip to Martha’s Vineyard, barbecues with Paul’s family (after more than twenty years they were my family too), a visit to Florida including a tour of Ernest Hemingway’s house (I have a photo of Paul in Papa’s WC), even the prospect of Marcel joining us in a week or two, could not silence the voice shouting in my head: ‘No. This is too much.’

One day Paul received a letter from a friend saying what a fine book My Secret History was, but how difficult its publication must be for me. He showed me the letter and for the first time seemed to want to know how I felt.

‘It is very hard,’ I said. ‘Sometimes I feel unhappy and afraid about the future.’

I hoped for reassurance.

‘Sit down,’ he said. ‘I’ve been meaning to tell you something.’

I knew what that meant. We’d been there before. I said it first.

‘There’s someone else.’

There was a long pause and the sound of wild horses exerting their best effort.

‘Yes. But it isn’t serious. I told her,’ he said with some pride, as if he expected me to be pleased, ‘that this had happened before, and that when I had to choose, I chose you.’

‘So it’s not her again?’

‘No.’

‘So who is it?’

‘Why do you need to know?’

‘Did you tell her you loved her?’

‘I may have done. But it wasn’t true.’

The mad, jealous questions and evasive answers began again. Much of what he told me then, later turned out to be untrue.

Feeling that I had been punched hard on an old wound, I went and sat in the toilet to be alone.

Later that day we drove to Boston to meet Marcel’s flight. Neither of us spoke for over an hour. As we entered the airport parking lot, he said, with a pathetic attempt at lightness, ‘Are you wishing that you’d had an affair too?’

‘No. I’m not wishing that. I was thinking that this probably really is the end.’

As he got out of the jeep he was crying.

Over the next few days we behaved as normally as we could, buying clothes and a duvet for Marcel’s first term at Yale, cooking and eating together as usual, visiting relatives, even taking a cycle trip along the Cape Cod Canal. If he had said then, or at any time in the next months, the next years perhaps, ‘I will always love you. This will never happen again,’ I would have done almost anything to keep us together.

He was about to leave for a two-month trip in Australia and New Zealand, the first stage of his research for The Happy Isles of Oceania, and we agreed to decide nothing before this was over. He said he wouldn’t see the woman during that time. He had told me that she lived in Los Angeles. He would travel to Australia without stopping there. I flew back to London; Paul drove Marcel to Yale and then set out on his journey.

During the two months that followed, he telephoned me many times at great expense to tell me that he loved me and sent me loving letters too, but he never said what I wanted to hear.

Other things were not going my way. I had returned to England looking forward to getting back to work. (I had given up my BBC staff job just over a year ago and was working as a freelance broadcaster.) Among the post I opened on the first day back was the new rota for the Radio 4 arts programme which I had been presenting regularly since the beginning of the year. My name was on it only twice over the next four months. When I telephoned to check, it became clear that I might not be needed at all the following year. Though this was not spelt out, I got the impression they had found another woman presenter to join the team and that they liked her better than me. Another rejection. The future looked bleak, professionally and personally.

Sometimes I behaved destructively, drinking too much and not eating. At other times I tried to be sensible: I spent a long weekend at a health farm (I still use the make-up they recommended) and I contacted the psychoanalyst who had worked with Paul and me three years before when we nearly separated because of the English teacher in Pennsylvania. She agreed to see me on my own. I still have the notes I wrote after the sessions, stored in my old Amstrad: Dr P suggested I’m not allowing myself to experience the full range of feelings because I exclude those which don’t seem useful or sensible. But I don’t know what I really do feel, except pain …

It goes on for page after anguished page – embarrassingly self-pitying to read now, but true at the time … some of the time. I listed all my stored-up grievances against Paul in an attempt to expel the anger the analyst said I was repressing, writing them down in the heat of rage. Now, reading them back, many of them seem petty: developing rival symptoms when I was ill; not helping enough with preparations when people came to dinner; being too tired to be supportive when I was in labour. When I came home from the hospital with Marcel, he didn’t look after me. On the Sunday he didn’t even get my lunch. When we flew back from Singapore to London, he just slumped on the bed in the hotel, leaving me to cope with the children. In Dorset I used to get up at 5 or 6, get breakfast for the kids, spend the whole day looking after them, getting meals, washing nappies. Once I was so angry I threw a bowl of cereal over his head. He never let me forget it. When I tried to tell him how unhappy I was, he said he had a book to finish. Sounds as though I was a pain in the arse.

My perspective has shifted. At the time I dragged up anything from the past that backed up the contention that Paul was a villain. There was plenty of evidence. So why did I want him to stay? Did I want him to stay? In this crisis, as in our falling in love and in our marriage, there were forces at work which I did not fully understand, however hard I struggled.

Today I had an illumination. I don’t want to end my relationship with Paul; I want to end the marriage. I want to get rid of the externally imposed restrictions and attitudes, the stereotypes of wronged wife, nagging wife, indulgent wife/mother and have my own life in my own house – which Paul will enter when it suits us both, not by right. I don’t hate Paul – I don’t believe the bitter things I wrote earlier.

My feelings were powerful and confused. I tried to simplify them and look at my choices. I could cut my losses and face up to life without Paul; I could embark on a battle with my latest rival (whom I could probably see off, as I had seen off the woman from Pennsylvania); or I could put up with the situation as it was, suppressing the knowledge that Paul would make love to this other woman, or a different ‘other woman’ when it suited him. None of these seemed right. Part of the trouble was that I didn’t know what Paul wanted.

He arrived back in London a few days before my 47th birthday, and for a while we resumed our life as if it were unthinkable that it should end. So much of the way we lived together was enjoyable and comfortable that I couldn’t believe he would want to give it up. And yet his infidelity and his uncertainty seemed to spring from a profound dissatisfaction with his life as it was: with London, with me, with the life stage he had reached, the father of sons about to take off on their own, leaving him behind.

During the last months of 1989, every evening on television, we watched the familiar world order shift before our eyes as communism crumbled in Eastern Europe. Our domestic life was also on the brink of collapse and we made a number of changes in a last-ditch effort to shore it up. We bought a new car, and new furniture for the living room to replace the second-hand sofa and chairs I had paid £20 for fifteen years earlier. I disposed of the out-of-tune piano which no one played and the collapsible table-tennis table which was stored behind it; these once coveted items had outlived their appeal and were now a source of annoyance. ‘When are we going to get rid of that bloody piano?’, he would say. ‘No one ever uses it,’ and I would prevaricate and maybe finger a few bars of ‘Für Elise’, or another piece remembered from childhood, as a sign that one day I would play the piano again. Now it went – for nothing, to the first person willing to take it away.

We tried again to talk about the future, to list our options together, in the way the psychoanalyst had taught us when we were racked by similar uncertainties three years earlier: to part for ever, to stay together for ever, to spend a year together, to spend a year apart, to spend a year somewhere completely different. In 1986 I had opted to spend a year together. Paul had agreed. Then he had gone on a short trip alone (part of the travels in China described in Riding the Iron Rooster) and come back converted. ‘I don’t want to spend a year together,’ he said. ‘I want us to spend the rest of our lives together.’ That was exactly what I had wanted but hadn’t dared ask for. We celebrated by travelling to Tibet, though in his description of the journey in the book, I am not mentioned.

This time, in 1989, my preference was for a year somewhere completely different: why not in the Pacific? I had always intended to accompany him on at least some of the journeys he would make for his next book. This could be our first long trip together, now that the children were grown up and I had given up my BBC staff job. In the past, when it had seemed hard to be left behind, while he explored places that I too longed to see, I had fantasised about a time when we would travel together, believing I could match Robert Louis Stevenson’s idea of the perfect mate.

‘I wished a companion to lie near me in the starlight, silent and not moving but ever within touch. For there is a fellowship more quiet even than solitude and which, rightly understood, is solitude made perfect. And to live out of doors with a woman a man loves is of all lives the most complete and free.’*

But that was Stevenson’s dream, and mine, not Paul’s.

‘Why not a year in Fiji?’ I urged, convinced now that this was what I wanted. Far away from pitying eyes, my hurt pride would heal and I would be able to forgive.

‘I don’t know.’ He had just returned from driving Louis to Oxford.

‘You said you knew someone who would let his house to us.’

He was silent.

‘It would be a base. You could still travel alone when you wanted to. I could collect some programme material.’

Eventually, unable to bear his unexplained reluctance, I yelled at him and shook his arm.

‘I’m afraid of you,’ he said, and I felt like an ugly monster. Who would want to be married to me?

We agreed on a six-month separation. It was the most either of us could contemplate.

We went to see a lawyer and drew up an agreement. We discussed how to tell my parents, and whether he should leave before Christmas or afterwards. Since I had already invited my parents and my sister’s family to spend Christmas with us, we decided it should be afterwards. Louis would be down from Oxford, Marcel would be over from the States, it would be a happy time to remember.

Of course it was horrible. My sister and her husband had been told we were going to separate; I don’t know what they said to their children, Sam and Max, who were then nine and six; Marcel and Louis knew only too well that our future as a family was in jeopardy. My parents knew nothing and seemed to enjoy their presents, the turkey and the Queen’s speech as much as usual. We played games: Cards in the Hat, Murder in the Dark, The Parson’s Cat and a new one which involved throwing dice and eating chocolate very quickly with a knife and fork as soon as you got two sixes; when the next person threw two sixes they had the right to take over the knife and fork and the chocolate. Inevitably this last game grew rough; Paul and my sons became over-enthusiastic (eager to win, I think, rather than eager to eat chocolate) and the youngest child, my six-year-old nephew, ended up in tears, while my sister tried not to be angry and my parents maintained a tactful silence. I shouted at Paul and my sons and we all felt ashamed.

Also on 25th December 1989, the Ceaus¸escus were executed by a firing squad.

For the difficult days between Christmas and New Year, I had planned a final trip for Paul and me – a visit to Florence. It was a last attempt to share my world, the best of Europe, at a time when he talked of wilderness and distant oceans. On one of the very last days in December we walked arm in arm through the Boboli Gardens and he said, ‘I’m beginning to feel there may be hope for us.’

‘I don’t think so.’

‘Why? Do you hate me?’

‘No, I don’t. But I despise you.’

He breathed in sharply and walked ahead of me down a flight of stone steps between two rows of conifers. I ran after him and took his arm.

‘Don’t be sad.’

Who said that?

*Travels with a Donkey in the Cévennes by Robert Louis Stevenson, 1879.