13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Elliott & Thompson

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

The memoirs of the last British Admiral to lead an aircraft carrier into active battle A story that covers Britain's most remarkable battleships and naval events of the recent past A unique view from the highest levels of the British admiralty "I slept that night in my top bunk, as we clattered over the rails. I imagined the ambush first, and a burst of fire ripping through our compartment, then wondered how I would cope with clambering down from the train in the darkness, knowing there were hostile insurgents about! Alas, I need not have worried, and we duly arrived safely in Kuala Lumpur in time for breakfast..." Born in Devon, Sir Jeremy Black began his naval life aged 13, as a Cadet under Training at Dartmouth and on HMS Devonshire. Then, cadets still slept in hammocks forced to lie on their backs to conform with the hanging of hammocks, a naval tradition dating back to before Nelson's time. He would learn seamanship and how to paint ships under the careful watch of Petty Officers, while in the classroom receive instruction on gunnery, torpedoes, signals and anti-submarine warfare. Cadet Black won the King's Sword after completing two long and intensive training cruises. His first appointment was on HMS Belfast (now a popular tourist attraction, moored by Tower Bridge), which took him to his initial taste of service under fire during the Korean War. Experience on other ships followed until, aged 30, he commanded a minesweeper engaged in action during the Borneo uprising. There, unfortunately, he failed to notice that many of the ship's stores were sold by the Chief Bosun's mate, resulting in Sir Jeremy's Court Martial on a record number of charges. He survived. His long, distinguished naval career has taken Sir Jeremy to nearly every part of the world where the British Navy was engaged in the last half of the twentieth century; from the Korean War, through the Suez crisis, and in all the main areas of possible conflict during the Cold War. Appointed to command the country's newest aircraft carrier, HMS Invincible, he took it and its men to the Falkland Islands, winning the DSO for his part in the conflict. He went on to become a Flag Officer, taking a number of ships to the Far East, ending his career as Commander-in-Chief, Naval Home Command, when he flew his Flag in HMS Victory, Nelson's Flagship. From dancing eightsome reels in Borneo to the complex and dangerous fight to win back the Falklands, Sir Jeremy blends the tale of a successful naval career with many cogent observations on how naval life has developed - not always for the best - over the many years of his exceptional career. Written with a wry humour, Sir Jeremy's keen eye for detail and some pungent opinions combine to render memoirs which entertain, educate and finally engage its readers in a life of service, well-lived.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 402

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

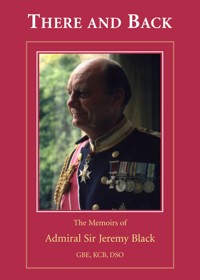

THERE AND BACK

The Memoirs of

Admiral Sir Jeremy Black

GBE, KCB, DSO

For Carolyn, Simon and Julian, and their families

CONTENTS

•

Title Page

Dedication

PageAcknowledgements

PageForeword

Chapter I Early Years/ Page

Chapter II Dartmouth – The Royal Navy Officers’ Training Establishment/ Page

Chapter III HMS Devonshire – As a Cadet in a Training Cruiser/ Page

Chapter IV HMS Belfast – As a Midshipman in a Cruiser/ Page

Chapter V HMS Concord – As an Acting Sub-Lieutenant in a Destroyer in the Korean War/ Page

Chapter VI At Greenwich/ Page

Chapter VII HMS Vanguard – As the Sub-Lieutenant of the Gun Room in a Battleship/ Page

Chapter VIII HMS Diligence – Ferrying Inshore Minesweepers/ Page

Chapter IX HMS Comus – As the Gunnery Officer in a Destroyer/ Page

Chapter X HMS Gambia – As Second Gunnery Officer in a Cruiser/ Page

Chapter XI HMS Diamond – As the Gunnery Officer of a Destroyer/ Page

Chapter XII HMS Fiskerton – A Coastal Minesweeper in Command/ Page

Chapter XIII HMS Excellent – As Assistant Long Course Officer/ Page

Chapter XIV HMS Victorious – As Gunnery Officer of an Aircraft Carrier/ Page

Chapter XV Staff Officer to the Flag Officer First Flotilla/ Page

Chapter XVI HMS Decoy – A Destroyer in Command in the Far East/ Page

Chapter XVII The Ministry of Defence – In the Directorate of Naval Warfare/ Page

Chapter XVIII HMS Fife – In Command/ Page

Chapter XIX HMS Invincible – Preparations for the Falklands War/ Page

Chapter XX HMS Invincible – The Falklands War/ Page

Chapter XXI Flag Officer First Flotilla/ Page

Chapter XXII Assistant Chief of Naval Staff/ Page

Chapter XXII Deputy Chief of Defence Staff (Systems)/ Page

Chapter XXIV Commander-in-Chief Naval Home Command/ Page

Chapter XXV Rear Admiral and Vice Admiral of the United Kingdom/ Page

Chapter XXVI Reflections/ Page

PageChronology

PageGlossary

PageIndex

•

A map appears onpage

Plates

PICTURE CREDITS

Copyright

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

•

My heartfelt thanks go to all of the following:

Pam, my wife, who has worked long and hard proof-reading the manuscript and I thank her most warmly.

Sandra Watts who has worked tirelessly typing and re-typing the script and Alison Hawes who conducted similar work prior to her arrival.

Peter and Elaine Mucci who gave me the enthusiasm to write down the story and helped me to sort out the publishing of the book.

Rear Admiral Sir John Gamier who was immensely helpful when the book was in its early stages, as was Captain Tony Sainsbury RNR.

David Watts, Sandra’s husband, who spent several hours reading my journals and has been most helpful with my choice of material.

Captain Ian Powe who advised me on the layout of the book and gave me an invaluable overview.

Finally, Lome Forsyth who advised me to go to the most helpful of publishers, David Elliott, who has guided me throughout.

FOREWORD

•

This is an account of my life in the Royal Navy, which began in 1946 when I joined the Britannia Royal Naval College straight from my prep school at the age of thirteen, as was customary at that time. The College had been evacuated to Eaton Hall, the seat of the Dukes of Westminster in Cheshire, as the buildings at Dartmouth were required for the planning of the war effort.

I continued to serve until 1992 when I retired as an admiral at the age of fifty-nine. I had enjoyed almost every minute.

I have sought to describe the professional incidents of my life in the terms and phrases which were in use at the time, and for the benefit of those readers who are not familiar with some of the words, there is a glossary at the back of the book.

Chapter I

Early Years

•

One night in November 1932, the church bells from villages on and around Dartmoor rang out in warning. A prisoner had broken out from the infamous Princetown gaol. The Black family, however, had other matters on their mind that night, even though their house, Mayfield, was situated in one of those villages – at Horrabridge, near Yelverton. Their third child was being born, and if their precise thoughts at that moment can now be only a matter of conjecture, no shock or surprise was ever mentioned or even hinted at by my parents. And this despite the fact my birth was unplanned and would occur some seven years after that of their previous child, Colin, my elder brother, and ten years after my sister, Elizabeth.

My father had left his seagoing career only a couple of years before. He was born Alan Henry Black in 1887, into the middle of a family of eight, six of whom were boys. As he grew up and did well at Greenwich Hospital School, his father, who worked in a bank, was keen that his son should follow in his footsteps. Alan, however, had other ideas. During walks through Greenwich Park, he got into conversation with an old man who was recovering from an operation. The old man’s tales were of adventures at sea, which excited and enthralled my father. On the last occasion of their meeting, the old man gave Alan a card, saying: ‘If you want to go to sea, take this card to the offices of Clan Mackenzie.’ His parents lost patience with Alan, and were disinclined to listen to him or support his emerging desire to go to sea. Alan took the card along to the office, and Clan Mackenzie arranged for him to become an officer cadet. It was then Alan discovered that the old man had been the Chairman of the company. Thus, my father sailed for Hamburg, to load for his first voyage under sail, to Australia.

My father served in several ships, primarily under sail, until he transferred to the Eastern Telegraph Company, who ran a number of cable-laying ships. Whilst serving in one of these, the Amber based in Plymouth, he met my mother, Gwendoline, whose father owned a shipping line, based in Plymouth. They were engaged in 1913, before the outbreak of the First World War. When war came he sailed away, not to return until after the Armistice, five years later. Despite such a prolonged separation, he and Gwendoline were married in Plymouth in 1918. His war had taken him to many places, not least to provide communications off the beachheads at Galipoli.

The new family, with two small children, Roger and Elizabeth, sailed to Cape Town, where my father now served as Chief Officer in a ship out there. After a year, they returned to Plymouth, where sadly Roger died, aged five, of encephalitis. Colin was born six months later, and the family moved to Gibraltar, where my father remained with the Eastern Telegraph Company – which became the mighty Cable and Wireless Corporation – until 1930, when he left the sea in order to spend more time with his family. I was born two years later.

The family underwent some turmoil as he attempted to find his next job and lived temporarily at Mayfield, a house they owned but usually rented to tenants. Colin and Elizabeth attended the local school in nearby Yelverton. Alan, my father, purchased a company called A. A. Rodbard based in Whimple Street, located near St Andrew’s Church in the centre of Plymouth. The company was renamed A. H. Black Ltd and it supplied the hotels and public houses within a fifty-mile radius of the town in all directions with their every conceivable need: chairs, tables, glasses, cigarettes, measures, biscuits and chocolates, all delivered normally on a weekly basis. There were clear benefits for the entire family – a weekly box of Black Magic chocolates and very often, at weekends, a trip to an appropriate establishment for a meal. This ‘marketing exercise’ was always followed by an invigorating walk around the surrounding countryside.

A year later, in 1933, the Black family moved into The Linhay on Russell Avenue in a suburb of Plymouth. It was an unusual house built on steeply sloping ground. The front door was entered from the road by walking across a wooden bridge, and though the door led into the hall and the main living rooms, it was the floor below which opened on to the large garden at the back. The frontage was wide enough to allow my father to build a tennis court and, when the Second World War broke out, to dedicate a plot of land to the growing of most welcome fruit and vegetables.

Beyond the house lay a copse and then a farm which meant, inter alia, that Devonshire clotted cream was always available. We would explore the Devon and Cornish coastline and frequently roam around the vast, volcanic spaces of Dartmoor, dotted with picturesque villages, often with burbling streams tumbling down from the hillsides into their attractive centres. I had that most valuable privilege, a childhood lived in a happy and supportive family, with modest expectations, and was also given the opportunity to explore and enjoy a surrounding countryside of exceptional beauty.

My father

This atmosphere of peace and contentment did not prevent my parents from noting the gathering storm clouds as Nazi Germany flexed its muscles and prepared for war. It is hard to imagine what the threat must have meant for a couple with three young children, who had already suffered four years of separation during a previous war, only twenty years earlier. There was also an added dimension – the awful spectre of air-powered bombardment, which could now involve civilians located many miles beyond the front line. This was all apparent to my father who, with the aid of his gardener, dug a First-World-War-type trench in the thick clay alongside the tennis court, covering it with railway sleepers and several feet of earth. Inside electricity was installed and wooden bunks were built, two deep along one side, though this arrangement was modified later on to provide an area for sitting.

When war was finally declared, my sister was boarding at a secretarial college on the South Coast and my brother had left his nearby prep school, 0Mount House, to start boarding at Blundells, located in Tiverton. I had graduated from my kindergarten, Busy Bees, to enter Mount House, which had then moved from Plymouth to a mansion on top of a hill just outside Tavistock. There I became a weekly boarder, travelling to school by bus every Monday and back every Friday. The parlous affairs of state during those early years of the war put pressure on even those as young as nine. The regular staff had gone off to fight, and the vast house could offer little heat, a problem for me which resulted in a constant battle with chilblains, a condition not helped by the daily walk along the drive for exercise.

The regime was rigorous. After rising, a nominated few would go down to lay breakfast while the rest remained to make beds and clean out the dormitory. Everything laid out for breakfast was to be eaten, even the spaghetti, at which I would stare long and hard, taking sometimes half an hour to pluck up the courage to get it down. We had to stack our own plates in a big machine before attending ‘cleaning stations’ to sweep and polish the hall, the stairs, the porch – whatever – and after morning lessons, there was more cleaning, but this time in the classroom. In summer we ran down the sloping gardens to the banks of the River Tavy, which separated us from Kelly College, and there we attempted to swim in the bitterly cold water. I am certain this experience ensured my joining Dartmouth some years later classified as a ‘backward’ swimmer!

My sister had been withdrawn from her secretarial college when the real danger of an invasion became apparent. She returned to live at home, joining the Woman’s Royal Naval Service to work as an Immobile Writer. It meant she was never drafted away and could continue to live at home. The drama of Dunkirk caused my father to disappear and join a yacht which was to be a potential evacuation craft, and the rest of the Black family, simultaneously, prepared for an airborne attack. The house was located within a mile or two of the Royal Naval Engineering College, at Manadon, where the sub-lieutenants already took part in anti-paratroop drills. As my father was then aged fifty, he was not called up into the regular services, but volunteered both for the ARP and the Home Guard; the role of the former was to keep watch in the area and take action as appropriate, and that of the latter to play a defensive part in the event of any invasion.

It was not long before my father’s ARP duties became very real because Plymouth soon suffered terribly in extensive nightly air raids. So while his family crossed their tennis court and made itself reasonably comfortable in its air-raid shelter, Alan patrolled his area with other air-raid wardens, all in helmets and carrying gas masks, first ensuring houses showed no chink of light, secondly pouncing on incendiary bombs – the principal offensive weapon – before another building was gutted, and thirdly assisting in the handling and evacuation of the local population. Every morning, after any raid, I would collect the shrapnel left lying around in the garden, fallen from our anti-aircraft shells.

Oil, so vital for ships, was stored in tanks at Staddon Heights, on the eastern side of Plymouth Sound. These were once bombed and set ablaze. In the light of the flames it was possible to read a newspaper throughout several nights as we sat on our doorstep and Plymouth itself presented the enemy with an all-too-easy target.

I remained at home during this time on the basis that it would be better if we all died together. Of course, Plymouth in its role as a naval base was a prime military target. My mother Gwen as well as being a JP often worked as a volunteer in a canteen opposite the dockyard gate, giving much welcome food and cheer to the many sailors stationed within. During one night of heavy bombardment she was there and my father and I listened to the high-exploding and whistling bombs with unusual trepidation. Eventually she did return. The house adjacent to the canteen had taken a direct hit as she and the other volunteers crouched under a table. As she tried to drive home, somewhat shaken, she reached Sherwell, only to watch the church blaze from end to end, unable to drive across the many fire hoses which had been spread over the road.

My father owned two business premises by then: Whimple Street and a storehouse situated on the quay by the Barbican. Wisely – and at the time, virtually uniquely – he had instituted fire watchers whose task was to patrol the roof during any air raids. They could take immediate anti-incendiary action, which was a mixed pleasure as a proportion of the bombs falling contained an anti-personnel high-explosive pack. As a result of this diligence, at the cessation of bombing his building in Whimple Street remained standing almost alone amidst extensive devastation. The rest of Plymouth’s centre was almost levelled, to be rebuilt eventually to an entirely new ground-plan. Although St Andrew’s Church was burnt down, Whimple Street still stands today, and one might say it is a memorial to my father. Within a quarter of a mile from his office, and set now in the middle of a large traffic roundabout, lies the burned-out shell of Charles’ Church, where my parents were married.

My mother (far left) with Lady Astor, Plymouth’s formidable MP

One night, as we sat in the air-raid shelter listening to the orders shouted to an ack-ack battery situated on the adjacent farm and the familiar drone of German bombers punctuated by the occasional terrifying sound of a whistling bomb, I heard the loudest explosion of our war. A land-mine blew up at Sun Gates, a Spanish-type house built within a quarter of a mile of our house, on the main road. The house disappeared and the nearby Roman Catholic old people’s home was wrecked. The explosion devastated a number of large Victorian houses opposite, hidden behind the trees in their gardens. Even the houses in our immediate vicinity lost their windows.

As the threat of air raids diminished, the walk in the cold night out to the shelter was rendered unnecessary by the acquisition of an indoor ‘Morrison’ shelter. It was a steel box, four feet high and with mesh sides, into which we, and any visitors, would scramble. In principle the box would withstand the collapse of the house and hopefully its inhabitants would be dragged out in due course.

We had an outbreak of chicken pox at school so our chests were inspected daily for the beginnings of the rash. One Wednesday morning I detected a spot which was easily concealed by the judicious placing of an arm. By Thursday the spots were more numerous, but around my waist. By Friday the rash was widespread. My objective was to get home by the regular bus on Friday evening, but the probability looked bleak. It seemed only the Lord would save me, and for some reason, never explained, our teacher that day was called away as the class drew to its close and the inspection did not take place. So far, so good and I boarded the bus home. The question now was when and how my condition was to be declared.

The following Saturday morning was to see the culmination of the ‘Ships for Victory’ week – such similarly focused charity weeks for the war effort were not uncommon. The form these events would often take was a march through the city of soldiers, sailors, airmen, the women’s services, including nurses and land girls, and units from the many European countries who had fled to the United Kingdom to join the fight against the Nazis. My family entered the throng of onlookers, enjoying the music of the many military bands, the colourful and varied uniforms and the sense of international camaraderie which the scene engendered. As the final contingents passed by I whispered to my mother that my chest was itchy. On our return home I quickly displayed my pimply chest, whilst feigning surprise, although I well knew what to expect. A happy couple of weeks followed in the bosom of my family as I nursed a mild attack of chicken pox!

After three years at Mount House, by which time I was ten years old, my parents concluded that the school and I were not suited to each other and rather than force me to fit in better, they sent me to the nearby Seafield School, originally from Bexhill in Sussex, but now evacuated to the Two Bridges Hotel, near Princetown. I warmed to the school instantly. It was less spartan in style and there were fewer domestic tasks; the hotel bedrooms were smaller and more comfortable than dormitories and a much warmer atmosphere was fostered by the school’s owners, Granville and Patrick Coghlan.

In those dark days when England and her allies were suffering one defeat after another there was a solitary spark of light when the Royal Navy – close to my heart even then – cornered the German pocket battleshipAdmiralGrafVonSpee in the Rio de la Plata off Montevideo and caused her to scuttle herself. During the action, HMS Exeter was singled out by the Germans and, in thirteen minutes, all her gun turrets were out of action. After the action she limped to the Falkland Islands where wooden guns were fitted, to disguise her parlous state, for her return to Devonport. She was a Devonport or ‘Guzz’ manned ship and was received on arrival with much acclaim, including a march by the crew through the city to have lunch with the Lord Mayor, all preceded by the carrying of Drake’s Drum. Lieutenant-Commander Dreyer (later Admiral Sir Desmond) was the Gunnery Officer.

Seafield engendered a wonderfully warm atmosphere, with schoolwork often punctuated by a day picking potatoes or making hay with pitchforks and riding carts on the home farm. We all played a somewhat watered-down military game with two sides within a fir plantation of several square miles. Sporting activities were unsatisfactory on pitches laid out at a twenty-degree angle on hillsides, but walks in every direction through adder-infested woods were a fine substitute. We jumped from rock to rock across the River Dart or climbed the rock-strewn tors in every weather. Rainfall was one of the highest in England and each winter we would be snowed in for a few days. It was wonderfully bracing for young boys and we enjoyed our daily spoonful of sticky malt to boost our calorie intake!

As D-Day drew nigh, Devon became the training area for the US services. Plymouth Sound reverberated to the noise of landing craft of all descriptions, whilst the Princetown area became a Divisional Training Site. Our lessons were enlivened by the music of artillery pieces, Piper Cub light aircraft landed on the roads and jeeps laden with GIs swept up to the hotel bar, which remained open. In 1999, my wife and I revisited the hotel. There was still a notice over the arched doorway between the hotel and the bar, signed by Granville Coghlan – ‘Seafield schoolboys not allowed beyond this point’! Immediately prior to D-Day a convoy of many and various military vehicles passed by on a road within fifty yards of the school. It continued nose to tail for thirty-six hours.

Schooldays

The subsequent peace treaty with Germany in 1945 enabled Seafield to leave the Two Bridges Hotel and return to Bexhill, and our purpose-built school. The facilities were, of course, much superior. Next door to it was a girls’ school which afforded a splendid objective whilst kicking a rugby ball into touch and also the privilege of taking their collection in the local church. Such thoughts must clearly indicate that it was time for me to move on and it was indeed my term to study and sit for Common Entrance. Though the teaching at Seafield was thoroughly satisfactory and the atmosphere both warm and supportive, I sometimes feel in hindsight that this was somewhat surprising. Granville Coghlan, whose son was also a student at the school, was separated from his wife (I never saw her during my entire three years at the school) and Patrick, his brother (and joint headmaster), who wore the darkest of dark glasses, developed somewhat close attachments to a few boys – relationships that these days might cause some concern.

The move of the school back to its Bexhill home coincided with my examination to join the Royal Navy, upon which my heart was set. A career in the Royal Navy was the only one I had ever considered or desired. Indeed, I judged the service offered a worthwhile, honourable, exciting and adventurous life. In reality, of course, I knew little or nothing of its true meaning at thirteen. The exams and interviews stood before me as a vital hurdle to be jumped in my final term; work, revision, ‘mocks’, dummy interviews were all faced with enthusiasm and the days to the sitting of the exams were anxiously counted down. With ten days to go and tension rising, I suffered a sore throat, instantly diagnosed as an attack of mumps. I fought tooth and nail to continue but very sensibly I was debarred from doing so and confined to my bed. Throughout the period of illness, the Common Entrance exams came and went. Could I catch up? And if so, how?

It’s not hard to imagine the drama. As a consequence I was one of only two (as I subsequently discovered) out of some three hundred hopefuls who sat a special examination set by the Admiralty, and which was delivered early one evening by a despatch rider. He switched off his headlights, dismounted and handed a set of papers to the headmaster. Shut in an austere room with a personal invigilator, I did my best. After a couple of weeks of anxiety, relief followed. Having satisfied their Lordships on that score, I was summoned to that imperial structure – or so it seemed – the Admiralty, for a medical examination and an interview in Queen Anne’s Gate. My journey up to London by train seemed propitious as all the magpies that we passed were in pairs. I realise now, looking back, that it was spring and therefore not so surprising.

‘Sit down, please,’ said this awe-inspiring sight, a real Admiral – and a full one at that – sleeves glistening with gold stripes, set off by gold buttons atop, with rows of medal ribbons earned in the war so recently passed. He was flanked by four other notables, one of whom was the headmaster of the Britannia Royal Naval College at Dartmouth, another a psychologist, and so on. Lurking in my mind was the thought that the forty-five places might already have been filled from among the 298 other applicants who had entered the race. The special circumstances ensured that the two of us who had been sick were the final two to be interviewed, which was for me, I suspect, a potentially more hopeful position than being with the Bs at the front of the queue. For whatever reason, David Gray, the other sick candidate, and I were both successful.

The Britannia Royal Naval College for officers was a custom-built, majestic red-brick building on the hill overlooking the town and picturesque harbour of Dartmouth. The cadets were evacuated in 1942 and subsequently a bomb struck it, killing a WRNS, who was in the lavatory. Later it was used as a headquarters in the build-up to and execution of the D-Day landings in Normandy. The College moved first and briefly to Miller’s Orphanage in Bristol but found a more lasting resting place at Eaton Hall, near Chester, the home of the Duke of Westminster, where I joined it for one term.

That day, standing on the station at Plymouth North Road dressed in the brand new uniform of a Cadet, Royal Navy, seemed to me like entering and becoming part of my nation’s history. I was frightened by the possibility of meeting a sailor from the naval base who might salute me. It would have thrown me off balance. Saluting was a lesson yet to be learnt. The journey to Chester was a long one for a boy aged thirteen, grappling with his luggage, and with both excitement and anxiety wrestling for supremacy as he tried to face so many nameless worries. The short journey from the centre of Chester was made in the back of a navy-blue three-ton lorry. I was thrilled to note its number-plate commenced RN …

Eaton Hall was a vast Victorian pile set in thousands of acres through which ran the River Dee. Immense though it was as a dwelling – even as a nobleman’s seat – it still needed enlargement. To house five hundred cadets, Nissen huts were erected in clusters in the immaculate grounds of the ducal mansion, each one to board a house of the College.

The Duke of Westminster, an old man, continued to live in his private apartments and probably hardly noticed us, although the ‘new entry’ house, specifically for us thirteen-year-old entrants, was accommodated in Eaton Hall itself. I don’t recall ever actually sighting the eminent being.

Chapter II

Dartmouth – The Royal Navy Officers’ Training Establishment

•

Lieutenant-Commander John Ronald Gower, Distinguished Service Cross, Royal Navy, faced a group of forty-five thirteen-year-old boys who had been gathered in the sunlight to have their photograph taken at the beginning of the 1946 summer term. As he looked us up and down on our first day in the Royal Navy, standing in our brand new uniforms, wearing our ill-fitting caps with shiny gold badges, the Lieutenant-Commander spoke gravely. ‘You have all joined believing one day you will be admirals. I have to tell you that if you are lucky, probably just two of you will make it.’ I would never forget his statement, which prophetically was realised some forty years later. Only two of us did indeed reach Flag Rank – myself and Roger Morris. We were both Plymouthians and graduates of Mount House School I have always found this to be an extraordinary coincidence.

The dining-hall was a series of huts joined together. It was forbidden to run there, though the rewards for arriving first could be significant. Each table had a half-pound of butter placed upon it, a commodity unknown to us except as a small two ounce object, our weekly ration for the war years. The first cadet to arrive at the table normally took between a quarter and a half of the butter block and each successive cadet took a similar proportion of that which remained. These winnings would later be shared with friends. Hence the high speed walk from Drake House, positioned in a wing of Eaton Hall, commenced as the clock in the Hall tower struck 4.30 p.m.

We slept in two-tiered metal bunks. Each of us first termers slept on the bunk below our Sea Father, a cadet of three months’ standing, a second termer. Although our two terms were to work together at our academic studies for the next four years, a barrier of ‘them’ and ‘us’ was inevitably erected, made manifest by the length of the lanyard which passed around the neck and threaded out through the lapels. On a first termer the lanyard passed straight across; each term it was hung a little more loosely, until by the eleventh term it practically reached our navels. We all wore a reefer uniform and shorts. The College was hierarchical, as of course was the Navy.

With the Royal Marines, aged 16

Our introduction to sailing was in a twenty-seven-foot whaler, under the command of a long-retired senior naval rating, called ‘Chief.’ The combination of a twenty-seven foot vessel in the narrow River Dee, with its overhanging hazel trees, a barely adequate coxswain, five raw cadets and with often very little wind, was a formula designed to squash any latent desires in the breast of a naval cadet actually to learn to sail. Worst of all, I sat not on the thwarts which seemed designed for that purpose, but on the bottom boards, beneath the thwarts. It entailed, invariably, acquiring a wet and cold bottom which got wetter and colder if the whaler heeled towards me. As at that time I had never capsized, and had thus no conception of the gentle process, I did become frightened at times. When a gust of wind ensured the water lapped over the gunwale I was even colder as it sloshed all over us, and I was suddenly aware that I might become trapped under the thwart and sail if the whaler ever turned turtle.

In essence, the College was similar to a public school in that its curriculum was as austere. The teaching of the Morse code, semaphore and the naval code of signal flags was additional to instruction in seamanship skills, such as bringing a ship to anchor, catting an anchor and undertaking replenishment at sea. There were parades of varying types, even one where we received our one shilling pay each week, and another every Sunday when we were inspected by the College’s captain. At the beginning of my second term and after my return from the summer holidays, we entered our Victorian custom-built college, overlooking the harbour at Dartmouth. It was the fourth school venue for me in four terms: Princetown, Bexhill, Chester and Dartmouth.

The Naval College organisation was unusual in structure. At its head was Captain Peverill William-Powlett, his deputy was a Commander and each house officer was usually a Lieutenant-Commander in his early thirties, who had distinguished himself in some way or other during the recent five years of war. Peter Dickens, DSO, DSC, was a coastal-forces ace and Loftus Peyton-Jones, DSO, MBE, DSC, had a most successful record in submarine warfare, but surprisingly, perhaps, never went on to a higher rank. In parallel with the naval officers were the academic staff, led by the headmaster, and bright and able as they often were, the teachers were definitely subordinate within the hierarchy. They were always known by their initials. My own tutor was called ‘DLP’, meaning de la Perelle or ‘deadly peril’, who eventually went on to a headmastership in Liverpool.

The day-to-day conduct of life in the school was the responsibility of the cadet captains, those at the top being Chief Cadet Captains, while House Cadet Captains ran their houses with three subordinates. Their function was to enforce punctuality for each day’s activities, organise and supervise ‘prep’ and conduct evening rounds of inspection in the dormitories. Each cadet, and there were thirty in each dormitory, would lay out his clothes according to an exact pattern on his sea chest, with clean shoes and clothes folded precisely. So ingrained did that inspection routine become that I still fold my dinner jacket when I travel in exactly the same manner.

A House Cadet Captain had the authority to beat his charges if, in his judgement, the offence warranted it and this he did perhaps a dozen times a term. All the cadets considered such punishment acceptable, even normal, and it did make one think twice before offending again. Repeated or more serious offences, such as smoking, might be referred to a higher authority. One could be beaten or ‘cut’ by the Chief Cadet Captain and there were ‘official cuts’, when ‘allegedly’ the Ministry of Defence would take the final decision. Such ‘cuts’ were always administered in the gymnasium, performed by a physical-training instructor, while a second one held the victim’s hands and a band of onlookers including the Captain, Commander, House Officer and doctor, bore witness.

As I entered my final year, my House Cadet Captain was Michael Parry. We had become friends. One evening, after ‘lights out’, he and I were chatting on the way to the bathrooms. A more junior cadet came up to him to report that his neighbour in the next bed had disappeared. He believed he was heading for the riverside at Sandquay, where the College moored its many sailing and power boats. Nothing like this had ever happened before. A party was raised to follow in pursuit and it reached the jetty just in time to see a picket boat proceed down the harbour. It was a balmy evening and Cape, a swarthy, lanky cadet known, unfairly, to his fellows as ‘Rape Cape’, was heading we knew not where and alone, in a thirty-foot craft. The news travelled round the College like lightning, despite the lateness of the hour, and endless suggestions were proposed as to Cape’s reasons and also, of course, his destination. Little was ever announced to the cadets. Cape, however, sailed through the night across the English Channel, dodging all the other ships, until, dead tired, he reached the Channel Islands. As luck would have it, the Home Fleet was anchored there for the weekend. No doubt, they had been warned and were on the lookout. In due course, Cape returned to the College where he was incarcerated in the school’s sick bay, out of communication with his fellows. I presume he was returned to his parents who lived, I think, in the West Indies. Suffice to say, we never saw him again, though his exploit remained a topic of conjecture for the whole College.

Chapter III

HMS Devonshire – Six Months in a Training Cruiser

•

It took me a few days after joining HMS Devonshire, a training cruiser, to learn to sleep in a hammock. Once in one, there is no other way of sleeping except on your back; there is no chance of ever turning over to change your position. My eventual deep sleep was interrupted as a bugler sounded reveille. Reaction to the bugle was instantaneous and I clambered out on to the deck. As the distance between each hammock’s centre was only eighteen inches, simultaneous lashing was always fraught. On this day, however, my neighbour on one side was Algy Scovell who, as he had kept the night watch, was entitled to a ‘guard and steerage: thirty minutes more of uninterrupted sleep. With my hammock lashed into a sausage shape, I lugged it to the stowage in the corner of the mess-deck. All the hammocks were stood there vertically behind a railing, which left the mess-deck clear for us to use and eat in during the day. In the years since then, their Lordships considered such hammocks, of a design well known to Nelson, as replaceable. Today’s sailor is strapped into a bunk with little headroom so his recreational space is curtailed and he is denied the comfort of remaining relatively still and secure in a cocooned berth. Perhaps it might have been a better solution to devise a coloured, zipped and modernised hammock.

When the reveille was sounded and if it was my turn to attend the quarterdeck muster – a muster of the watch to scrub the teak deck – I dressed at full speed, though left off my shoes and socks, so as to arrive for scrubbing down in bare feet. Within ten minutes we would be ranged shoulder to shoulder, each with a long handled scrubbing brush, progressing slowly for’ard then aft along the main top wooden deck as salt water sloshed around our feet. On one particular morning, the Devonshire was in Bantry Bay as the sun rose like a fiery ball in the east. It felt quite different from those other mornings when we had to scrabble over ice-covered decks at Devonport. At other times, if I had been on watch during the night, my guard and steerage entitlement allowed me to stay there and spend a further precious half-hour in slumber.

After half an hour we were released from scrubbing to shave, shower and dress, wrestling for space in a crowded and often flooded bathroom, mess-deck or chest flat, where each of us had only a seaman’s wooden chest in which to store our clothes. For breakfast, we went back to the cleared mess-deck to take our places on benches at a long wooden table. Food was placed at the end of each table in huge trays by two mess members, called on that day ‘Cooks of the Mess’. They would be piped to the galley ten minutes ahead of the meal. Following the hastily eaten meal, they had to wash the cutlery and plates in what had became filthy water in a special mess kettle, and wash down the table and the deck underneath it. They used a couple of loosely woven cloths which, although they were replaced periodically, transmitted their smell to the plates and cutlery. Finally, the ‘Cooks of the Mess’ took the kettle to the gash shute up on deck to empty it. They would often hear the tinkle of a precious fork or spoon on its way to the ocean floor, never again to be available for the use of youthful diners.

Time allowed no pause before we all fell in at ‘Both Watches of the Hands’, in front of the Commander, once again John Ronald Gower, and the assembled Divisional Officers – in my case ‘Sus’ Spender, an experienced wartime submariner. The Devonshire sailed to Ireland and Bantry Bay, direct from Devonport, to start the summer cruise to the Baltic. We were to prepare the ship for the voyage. Primarily this entailed painting the ship’s side. As Maintop cadets we ‘owned’ a proportion of the side of this pre-war county-class cruiser which was nearly eight hundred feet long and stood thirty feet above sea level. Cadets split into pairs, each armed with a paint stage, a five-foot plank with a cross piece near each end, and a length of two-inch hemp. The rope would go round a guard-rail stanchion and pass around the cross pieces on the paint stage. The cadets climbed over the side and down on to their stage, after which a pot of paint and two brushes were lowered down to them. Once the side before them had been painted – it had already been scrubbed to remove any salt – the two cadets took the turns of their supporting rope gingerly off as they attempted to lower the stage to the next position. Some mishaps were of course inevitable. If one end of the stage fell, both cadets toppled into the water or else they clung on, hanging from the stage. Such events were an amusing diversion, especially if the sea was warm. Once they reached the bottom of the ‘fleet’, a motor boat would collect the cadets with the stage and return them to the gangway so that they could start again.

Scrubbing, painting, varnishing or keeping watch on the bridge or in the engine room were the main events of every cadet’s day. We were experiencing life as real sailors, but this process was interspersed with instruction on navigation, radar theory, signals, the ‘Rule of the Road’ and other, more theoretical, subjects to further our careers as naval officers. There were those who thrived on this way of life, but for me it was an existence which simply just had to be survived. I took the attitude that if I was to get through it all, it was probably worth going the extra mile and working as hard as I could. I was rewarded after six months with the King’s Sword and sundry other prizes for Navigation and Seamanship. It seemed an outcome full of promise, as were other moments of success, and in this case it led to the best appointment possible at the next stage in my career, on HMS Belfast, which was then fighting in the war in Korea.

One of the compensations for the daily grind of being a cadet in the training cruiser was the chance to travel abroad. This was a new experience for me, indeed for my whole generation. Travel had been denied us due to the war and the economic situation which that created. The voyage to Bantry Bay was my first step outside the United Kingdom. Later that summer we visited Norway, sailing up the 150-mile-long fjord to dock at the small town of Hardanger, nestling under the mountains, where lived no less than five Norwegian gold-medal-winning Olympic sportsmen! The scenery, as we made our way up the windless, clear fjord bounded by mountains rising thousands of feet above us, was breathtaking.

The fjord up to Narvik had a different ambience, for there the Royal Navy had fought two historic battles in the dark days of 1940 and our gunnery officer, Lieutenant Commander Harold Dannreuther, had been present. He was able to tell us of what he had seen of an engagement that ended in the award of a Victoria Cross to Captain Warburton-Lee. In Oslo we were visited by the remarkable Thor Heyerdahl. Parachuted into Norway, Heyerdahl had been the radio operator in the famous raid which blew up the heavy water plant from which the Germans had sought to obtain a major ingredient vital to their development of an atomic bomb. This action by five brave and resourceful Norwegians had possibly saved the Allied campaign and Thor Heyerdahl had been awarded the DSO. In later years he was to become even more famous, sailing the Kon-Tiki, a raft, from Peru across the Pacific Ocean.

From Narvik we sailed north into the Arctic Ocean, where we encountered fog before finally reaching ice. At one stage, with visibility down to a couple of cables as we worked as usual on deck, a mine floated past. It left us all with an uneasy feeling. A leading seaman in my part of the ship, who unusually had won a DSM during the war, went for’ard to the paint shop which lay, as was customary, in the eyes of the ship at the bottom of several ladders. There was a perceptible though not enormous swell. It was movement enough, however, to cause something to shatter the thick glass scuttle in the paint-shop flat. A shard of glass flew across the space and struck the leading seaman in his jugular vein as he was halfway up the ladder. There was nothing that could be done for him. The poor man, who had survived the war, bled to death while others watched helplessly.

After a couple of weeks on leave we sailed again, this time for the Mediterranean with a first stop in Gibraltar. As we sailed south through the Bay of Biscay we experienced a long swell from the west which caused us to roll so much that I felt seasick. I spent an entire day sitting on the deck feeling very cold and miserable until at last we reached the sunny bay of Gibraltar, with that most imposing and enticing Rock standing before us. My father had told me many stories about the Rock. He had spent time in Gibraltar when his ship was based there in the 1920s. My mother had lived there with him. He remembered how the gates of the town would be locked each evening. Imagine my disappointment when I realised I was in the duty watch that evening, our only day in port, and worse still, that we were to spend most of the evening loading in the wardroom wines. I could not go ashore.

We sailed next across the Mediterranean to Crete. Entering the natural harbour of Suda Bay we saw an eerie sight. The bay had been the scene of fierce fighting during the war and, alas, a stricken cruiser, HMS York, lay sunk on the bottom of the bay, its superstructure clear of the water from its deck level upwards. We ‘ran ashore’ that night in our shore-going uniform, sports coat and trilby hat, and enjoyed our first visit to a Mediterranean port by gorging on grapes. They were ripe, delicious and barely known to any of us. Food rationing and shortages had meant that most fruits were hardly ever imported to England and the taste of grapes was certainly unknown to us twenty-year-old cadets. The momentary pleasure was immense, but the resulting diarrhoea lasted for six weeks and was a difficult condition to manage in our minutely structured lives.

Whilst at anchor in Suda Bay, the Maintop division, under the command of the Divisional Officer, set off in boats – motor boats, huge cutters and whalers – for a ‘banyan’, or picnic. We were to live for two days on the beach. To get things organised, we split into three groups; one group erected a tent over which hung a ship’s awning, another gathered kindling and firewood and the third commenced cooking. As the evening drew in and the light faded, we all sat in the tent, around the fire and sang bawdy songs! When we woke the next morning ‘Sus’ Spender espied a peasant on his donkey, with two barricoes slung on its flanks. By conversing in sign language, he established that they contained wine. ‘Sus’ was thrilled. He offered to swop his shirt, which he claimed to have worn in the war, for the wine. However, his excitement about the deal cooled when he attempted to drink the raw, unpalatable liquid.

After a visit to Cyprus we headed west, emerging one morning to see the sun rise over Mount Etna. We made passage through the narrow Straits of Messina, where lay the infamous twin perils of Scylla and Charybdis, and passed close at night by the island of Stromboli as the lava from its volcano shot into the air and flowed down its slopes. Vesuvius dominated Naples Bay and we came to anchor on a perfect cloudless morning off the sheer-sided harbour of Sorrento. On a visit to Pompeii each of us was again identically dressed in sports coat and trilby