18,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

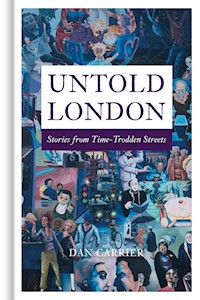

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

'Just pick up a copy and set off. You'll be amazed at what you've missed.' - Sir Michael Palin March, 2020: A columnist watches as London locks down, facing a conundrum as his weekly deadline for his newspaper diary approaches. With the city shutting up shop and column inches to fill, journalist Dan Carrier takes to the deserted streets of Central London to uncover the forgotten stories the heart of the UK capital holds. Untold London is a consideration and celebration of a city whose famous landmarks and thoroughfares are often taken for granted. Setting out to find lingering evidence of days gone by, Dan reveals unexpected delights, triumphs and tragedies alongside plenty of skulduggery and scandal in the greatest city in the world.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Sammlungen

Ähnliche

Praise for Untold London:

It’s sometimes important to see the things you love through other’s eyes, and in Untold London Dan Carrier has whetted my appetite for my city, just as I was beginning to take it for granted. He’s the perfect on-street companion: insatiably curious, generous, good humoured, scurrillous where necessary, pointing out the fine detail that makes London the most interesting city in the world.

Just pick up a copy and set off. You’ll be amazed at what you’ve missed.

Sir Michael Palin

I have this image of Dan doing everything on the Camden Journal - which of course is an award winning local newspaper, regularly voted the best in the country, if not the planet. Dan seems to write most of it - and I am sure gets up at six in the morning to deliver it, door to door, before he starts a day’s work. He is the most enterprising journalist I know, and the most committed, with a strong social conscience. I admire everything he writes.

Hunter Davies, OBE

While the rest of us were locked away in our flats and houses during lockdown - Dan Carrier was touring the city. In his imagination. These extraordinarily fascinating essays take us on a personal, historical, biographical ghost-ride around the crevices and crannies of the capital city - a place that Dan knows better than anyone else. His curiosity and knowledge are evident on every page - as is his deft skill as a writer. He’s a ‘Boz’ for our age - and these his loving sketches of a city situated somewhere between sleep and waking.

Kevin MacDonald

Untold London is a good read - wide-ranging, lively, entertaining, surprising, and written with a lifelong journalist’s skill and curiosity.

David Gentleman

First published 2022

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Dan Carrier, 2022

The right of Dan Carrier to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 8039 9225 9

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

PREFACE

Every Thursday morning, the drill would be the same.

I would sit down at my desk, roll up my sleeves, twiddle and stretch my fingers like a concert pianist about to embark on a marathon bit of Scott Joplin, and get started, rustling up 1,500 words for a column in the Westminster Extra.

The content was based on whatever had tickled me over the past seven days. It was fun to do – a way of decompressing after working for a weekly newspaper that goes to print on a Wednesday night. Interviews and gossip, quirky news, opinion and observation, review and preview, historical bits, the odd urban myth, and honourable mentions for anything else that had piqued my interest over the previous seven days.

On 23 March 2020 the coronavirus pandemic had crept in our direction, starting as a sparsely covered news item in January about something happening a long, long way away, to the virus reaching Italy in February, and then moving with frightening speed through our nation, just as the first crocuses appeared.

Certainly interesting times to be a newspaper reporter, and having found myself in the midst of the biggest story myself or my colleagues had ever covered, my gentle musings for the Westminster Extra Diary page had been shoved to the dustiest reaches of my mind in the week we went into lockdown.

But there it was, the regular Thursday deadline, virus or no virus and there I was, with a blank page to be filled and more fear than joy in my heart after what had been a week of frightening news from uncharted territories.

There were no gigs or exhibitions I could now preview. My attempt at light-hearted jape-y tales were redundant, and felt disrespectful and flippant. Other papers had already done the ‘Top 10 Lockdown Books’, the ‘Shows that have Gone Online’, and other hastily scrabbled together cultural features for the non-news sections. I didn’t feel much like reading lifestyle in virus times pieces elsewhere, so the idea of bodging together something similar from listings on the internet for my page was an unattractive morning’s work.

I sat back at home, still getting used to the new non-office-based idea of work, and thought about those empty streets just beyond the front door.

I felt wistful, pining, and wondered why slow walkers along Oxford Street or packed Tube carriages, the Chuggers and litter and garish lights and expensive food, and all those other irritants, had ever given me the grumps. To see it all now, I thought, and decided I felt homesick, despite lying back on my sofa at the time.

There are writers who make you feel nostalgic for a city that one may never have known personally, that ceased to exist long before you were born, but was created by our ancestors and whose foibles and characteristics we have inherited. HV Morton’s gently slanted insights through his In Search of … series, JB Priestley’s more honest and considered English Journey, and then all those wonderful London writers: Norman Lewis, Patrick Hamilton, Dickens, and Pepys.

Without being able to walk down streets we take for granted, and thinking of descriptions of what we were missing, I had a topic for the next edition. I would write a soppy but heartfelt message to my city, and ask the reader to take my hand on a journey through time and place, and remember, discover, investigate.

As I cast my eye over the streets I knew well and had therefore taken for granted, the reasons behind telling their stories also struck me.

‘It is a curious characteristic of our modern civilisation that, whereas we are prepared to devote untold physical and mental resources to reaching out into the further recesses of the galaxy or delving into the mysteries of the atom – in an attempt, as we like to think, to plumb every last secret of the universe – one of the greatest and most important mysteries is lying so close beneath our noses that we scarcely even recognise it to be a mystery at all,’ author Christopher Booker once wrote.

He was considering why we tell each other stories.

‘At any given moment, all over the world, 100s of millions of people will be engaged in what is one of the most familiar forms of all of human activity,’ adds Booker. ‘In one way or another they will have their attention focused on one of those strange sequences of mental images which we call a story. We spend a phenomenal amount of our lives following stories: telling them; listening to them; reading them, watching them being acted out on the television screen or in films or on a stage. They are far and away one of the most important features of our everyday existence.’

Bearing this in mind, recalling the tales heard, read, imagined between the covers of this book felt a good way to remember what had gone before us, and remember that such things would happen again.

It wasn’t planned this way. After finishing the first instalment, I wanted to carry on a virtual exploration, so I did. And so it continued throughout the pandemic, and, with a few tweaks here and there, that is what you will find in this book – a lockdown love letter to our city.

I’d like to send many thank yous to Joyce Arnold for all her help over the years, not least with the text you are about to read.

The following yarns are for my dad, who loves to tell a story, and for Juliet, Luc and Laurie, who listen patiently to mine.

DOGS, DOLPHINS, DANCERS AND DINERS

We had been due to go to Manchester Square and visit the Wallace Collection but our vague plan to take in an exhibition with a peculiar subject matter was scuppered. Central London was out of bounds, unless on urgent business, and looking at art inspired by dogs did not fall into the relevant category.

When you live in London (and I imagine it is the same for other dyed-in-the-wool city dwellers who have a cradle-to-grave relationship with the urban neighbourhood of their choosing), you feel like you are on the doorstep of the world.

To be told this vast, rich, inspiring cornucopia is off limits and out of bounds for the foreseeable is a lot to take in, so we decided to look into the future, a future when this horrible airborne virus no longer seeped through our streets. Perhaps, we thought, a period of enforced absence would make the heart grow fonder, would remind us why we lived here in the first place. To feel cut off while pretty close to living in the bull’s eye, one of the most vibrant and connected places in the world, was a strange contradiction. We asked ourselves what was it that we cherished, and what it was we were missing. We cast our mind’s eye over rooftops and recalled the stories of the streets.

London is the greenest capital city in the world, with one-third of its land allocated to public open space, and 48 per cent turned over to green spaces of all kinds – knocking New York’s 27 per cent and Paris’s 9 per cent literally out of the park.Ah, to be strolling in one of our parks with an eager dog pulling on a lead. Instead, let us find satisfaction in the thought that the Wallace Collection in Manchester Square, then closed for the duration, has more than 800 depictions of hounds in its possession, ranging from paintings to porcelain, furniture and even firearms.

A gallery in the afternoon, and then on to the theatre, where the range of shows waiting to once more entertain is bettered nowhere else in the world. Such diverse delights once included a performance at the Peacock Theatre in Soho, owned by porn baron Paul Raymond. In the 1970s, a popular afternoon pastime was to watch a show that included a tank with two dolphins being raised up on the stage, where they would perform tricks, culminating in removing the bra from ‘Miss Nude International’ with their teeth. Later, the theatre would become home to the TV programme This Is Your Life. The dolphins’ tank still remains beneath the stage.

After such theatrical delights, join members of the Beefsteak Club, an after-show dining society formed to discuss a heady mix of intellectual titbits focusing on theatre, liberty … and beef. Established in 1705 and still meeting at 9 Irving Street, just off Leicester Square, you can’t rock up wearing just anything. The strict dress code is blue coats and buff waistcoats with buttons proclaiming ‘Beef and Liberty’. To avoid having to remember the names of your fellow diners, once you are inebriated on a good crusted Madeira, the custom is to simply call everybody – even the waiting staff – Charles.

And while we’re ruminating on the performances currently postponed, oh to stroll down to the stalls of the lovely Savoy. When the late Charlton Heston appeared in A Man for all Seasons in 1987, he was told by the make-up team he would need to wear a wig. Chuck already sported a toupee – but was too shy to tell the person making him up. He therefore appeared on stage wearing a wig, on top of a wig.

‘Brizo, A Shepherd’s Dog’ by Rosa Bonheur, 1864. (© The Wallace Collection, London)

Ede & Ravenscroft, originally wig makers to the judiciary.

And while we are thinking of the Savoy Theatre and hairpieces, head eastwards a little along The Strand to the Royal Courts of Justice, and check out the scalp-warmers on display. The horsehair wigs the legal beaks perch atop their heads are based on a patent filed by Humphrey Ravenscroft in 1822. And they’re not cheap – the going rate for one is £700 upwards. Ede & Ravenscroft still have a wig shop around the corner from the grand court house, and as well as wigs they specialise in that particularly swanky and silky type of smart tailoring those on a legal professional’s salary like to indulge in.

Joseph Bazalgette.

From here, how about heading over the road and south for an amble along that most London of landmarks, the Embankment. It was warmly welcomed by Londoners when work finished in the 1860s, bringing some order amidst the chaos of the Thames banks.

Charles Dickens wrote to his friend William de Cerjat, who lived in Switzerland and had not had the pleasure of gazing along the new riverside, saying, ‘The Thames embankment is (faults of ugliness in detail apart) the finest public work yet done. From Westminster Bridge near Waterloo it is now lighted up at night and has a fine effect …’

Designed by the famous Sir Joseph Bazalgette, he of sewers fame, it was actually built by an engineer called Thomas Brassey. Brassey is better known for his role in constructing railways, and so prolific was he that it is estimated that by the time of his death in 1870 he had built one mile of every twenty railway tracks around the entire world.

And finally, while we’re thinking about trains and tracks, let us not forget how incredible it is that we can descend down a moving staircase to hop on a metal cylinder that will whoosh us to another bit of our home town – although should it actually be called the Underground, when 55 per cent of its 249-mile network has sky above it?

THE TUBE MAP MAESTRO

We embark on this marvel of late Victorian and early twentieth-century engineering, and pause for a moment on the platform, with its ox-red tiles, improve-your-life-you-miserable-commuter adverts and LT info-graphics, dusty dot-matrix schedule signs and Mind the Gap strips of yellow, to remember Harry Beck and his Tube map.

It is a story worth retelling, and doing so with the help of the late Ken Garland.Ken is one of that generation that came of age in the aftermath of 1945, born of an era where a war-forged sense of communal responsibility gave us a generation of highly educated, highly motivated people who greatly enhanced our creative economy.

He died in 2021, leaving a studio packed with original work that has become an unconscious motif in the public mind: from early posters for CND that helped popularise the famous peace sign, to designs for the toy maker Galt that every child in the 1960s and ’70s would recognise, he spent a life creating graphic iconography that was pleasing to the eye.

When Ken moved to London from his native Devon via National Service in the Parachute Regiment to study art at the Central School of Arts and Crafts he was, at first, slightly overwhelmed by the size of the city and felt a little lost in the bustle. Travelling from his coin-slot gas meter and soggy-mattress digs in the lodger-land of Earl’s Court, London’s sprawl was at first disconcerting.

That was until he got on the Tube and studied the Beck map.

Never before had he seen such striking graphic design, making easy to understand and frankly beautiful logic from the swirling mass of streets and buildings above ground. The map announced a new London, and inspired cities around the world to follow our capital’s lead.

Ken decided he had to meet the man behind this simple and effective piece of genius. He learned Beck was teaching at the London College, so he headed there and one lunchtime and found Mr Tube Map in the college canteen. Ken explained why he had come, and the pair struck up a lifelong friendship. Ken would sit in on Beck’s lectures and write a biography of him.

‘I turned up unannounced and asked around for him,’ Ken told your correspondent. ‘He was in the canteen and so I introduced myself. He said pull up a chair and got me a coffee. We became firm friends. The Tube diagram is one of the greatest pieces of graphic design produced, instantly recognisable and copied across the world.’

Harry Beck died in 1974, but not before he had told Mr Garland the story behind the diagram. He was 29 and had been working for the Underground as an engineering draughtsman since 1925, travelling to an office in Victoria from his home in Highgate Village. ‘I must have lived a very energetic life in those days,’ he told Ken. ‘Rarely missed my daily dip in Highgate Pond before breakfast and I was in the rowing club and the Train, Omnibus and Tram Staff Philharmonic Society.’

Harry Beck.

When the cold winds of the Great Depression swept across the Atlantic, grandiose plans to expand the Tube network were mothballed. This included a deep, fast-track line to zoom passengers from north to south, stopping at just the main stations. As well as projects iced, employees were laid off – and Harry was one of them.

His time out of work did not last too long, thankfully. The London Underground bosses came knocking – work piled up in his old office and because he had been playing in the transport orchestra, his former colleagues decided he really was the most irreplaceable of those laid off. So in 1933, Beck was re-employed – a decision that would lead to the creation of the greatest transit system map ever committed to paper.

Before being given his cards in 1931, Harry had often looked at the Tube map and felt there was room for improvement. Although geographically correct, the swirling lines and bunched up stations in what is now Zone One were, he felt, confusing. It was a map made using Victorian design principles and aesthetics, not a neat, eye-catching, easy to understand piece of graphic design. In Harry’s eyes, it did not do this futuristic transport network justice.

‘Looking at the old map of the railways, it occurred to me that it might be possible to tidy it up by straightening the lines, experimenting with diagonals and evening out the distances between stations,’ he told Ken. His colleagues in the engineering department thought he’d hit on a good wheeze when he showed them his plan for a neater Tube map – but the Underground’s publicity team were not convinced.

While unemployed, Harry continued to lobby them and in 1932 they relented, printing an initial run of 750,000 of his Tube maps, and then gave him his old job back. Beck would constantly update and improve the map – not least because this was an era of Tube expansion – but his hard work did not bring him the rewards that surely the creator of such an icon deserved.

The Underground paid him 5 guineas in total – and nothing more, at all, ever … despite his invention becoming as ubiquitous when talking about the Tube as the roundels used for station names. This meagre sum, considering the map’s eventual worth as a marketing tool, would rile Beck in the years to come, as did the occasional clumsy changes made to his original design, which would see him fire off a letter offering better ways to improve his work.

Your correspondent got to know Ken and once heard the following story. It comes with a disclaimer that it may be just a nice, slightly twisted, anecdote. However, the outcome is certainly what happened.

When Beck died, he left no children or a wife. His niece was tasked with clearing out his home, and as the story goes, she spent hours carrying heavy sacks of books, sketches, papers and manuscripts downstairs and into the street. Ken came to lend a hand, and noticed, in a skip the niece had hired, sketch books that contained Beck’s first ever drafts of the map we know. He rescued them and, being of a civic-minded nature, donated the electrical circuit diagram-like sketches to the Victoria and Albert Museum, where they remain today.

‘I had a secret admiration for him – I admit it was a bit of hero worship,’ recalled Ken. ‘His map was groundbreaking – it was only about connections and not geographical. This meant he could use only horizontal, vertical and diagonal lines. It was not to scale – the central area, which was congested with stops, is enlarged compared to the outlying areas.’

And as we conclude the story of Ken and Harry and the Tube map, here comes a train. Let us hop on board and head north, back into the heart of our town, and see where our noses take us.

PICCADILLY PECCADILLOES

From Embankment Station – which first opened for trains in 1870 and was built using the cut-and-cover method, and then had deeper Tube lines added in 1898 – we can catch a train on the Circle, District, Northern or Bakerloo lines. Let’s hop on the Bakerloo line and alight at Piccadilly Circus, normally a byword for London’s throbbing throngs, now eerily empty.

Deserted of its usual pedestrians, we can stop to admire the statue of Eros in all its glory. The statue of the Greek God was erected in honour of Anthony Cooper, the 7th Earl of Shaftesbury, for all his work looking out for the poor of London in the nineteenth century.

Ah-ha – but here’s the thing: it isn’t a statue of Eros at all. Instead, sculptor Alfred Gilbert, who cast it in 1885, modelled the figure on Eros’s brother, Anteros. We’ve been muddling him up with his bro all this time, but despite the general ignorance over who he actually is, Anteros is very much loved by Londoners.During the Second World War, the statue was removed for safekeeping – and put back in time for VE Day so that jubilant revellers could clamber all over the misnamed sibling.

Londoners have long treated the statue as something more than a piece of public art. Unlike similar installations, which very much have a ‘keep off’ vibe about them, Anteros has a more embracing relationship with the people who swirl around its base. When it was first unveiled, the West End flower girls set up stations around its base, using its fountain to keep their blooms looking fresh. A set of copper taps had been installed, to provide fresh drinking water to thirsty pedestrians. They didn’t last long – the taps were pinched within a week, and when their replacements were also quickly filched, it was deemed too expensive to keep replacing them.

It is incredible to think that Piccadilly Circus as we know it today – and apart from the types of vehicles clogging up the thoroughfare, would also be recognisable to a time traveller from the Georgian period – was under threat of wholesale redevelopment in the 1960s. That decade, where car was truly king, planners envisaged high-speed dual carriageways whisking the pampered commuter into the centre of the city. The remnants of these frankly awful schemes – fought off by grassroots campaigns – are the Westway and Park Lane.

Piccadilly Circus.

Our internal combustion engine champions at Westminster Town Hall could not resist the urge, suffered by every generation, to undo and fix up, make good and alter what has come before, pasting their tastes like layers over every building and every street. As the 1960s progressed, planners cast unforgiving eyes over the ragtag mixture of buildings and organically evolved streets snaking off Piccadilly with apparently no rhyme nor reason. Ideas were floated. Opportunities discussed. One such scheme, which remarkably gained traction, envisaged a row of thirty-storey office blocks around Piccadilly Circus, linked to Leicester Square, Shaftesbury Avenue, the Haymarket, Brewer Street and Regent Street by raised walkway, 60ft up.

At ground level, a six-lane dual carriageway would whisk traffic west to east, signalling the ultimate triumph of the car over the city. Perhaps planners backed down due to the pressure applied by a coalition of residents, activists, councillors and civic groups. Perhaps the 1973 oil crisis put paid to it. Regardless of the reasons, the scheme was shelved, but not before it had caused one unpleasant side effect. Speculators, knowing that something was a foot, bought up as much property as they could – and of course wanted a return. The project, which never got further than sketches on a drawing board, pushed up the costs of living in central London, and added to the long-term trend of small businesses declining in numbers in the surrounding side streets.

PELICANS, PARAKEETS AND SIR HUMPHREY’S NUTS

From Piccadilly, let’s potter south down Waterloo Place to saunter through St James’s Park. As well as being rather pleasant sculptured gardens, there are the pelicans to look out for: the park has five in situ, and they are the direct descendants of a pair given to Charles II in 1664 by the Russian ambassador (great present – remember readers, a pelican is for centuries, not just Christmas, etc). Park keepers keep them topped up with 12lb of fish each day.

Diarist John Evelyn wrote in 1665 of his fascination with the pelicans he came across. While not so well known as his contemporary Pepys, Evelyn witnessed and wrote about the execution of Charles I, the death of Cromwell, and both the Great Plague and the Great Fire of London in the 1660s.

Evelyn wrote about politics and culture – but he was also a gardener, and was drawn to St James’s Park to see what latest wheeze the king had come up with. He wasn’t disappointed: ‘I saw various animals and examined the throat of the Onocrotylus, or Pelican, a fowl between a stork and a swan; it was diverting to see how he would toss up and turn a flat fish, plaice or flounder, to get it right into his gullet at its lowest beak, which, being flimsy, stretches to prodigious wideness when it devours a great fish.’ He also encountered ‘deer of several countries, white, spotted like leopards, antelopes, an elk, red deer, roebucks, stages, Guinea goats and Arabian sheep’.

As we will discuss shortly, Trafalgar Square is no longer a prime spot to feed city scavengers and come up close to the feral wildlife that has as much a sense of ownership of this city as we do. Instead, if the urge to break bread with smaller creatures takes you, St James’s Park is the place. The descendants of James II’s pleasure garden menagerie today include the well-entrenched populations of parakeets and squirrels. They no doubt enjoy a lazier and more fruitful life than their forebears, who had to keep an eye out for the two crocodiles James I had installed in the lake after being gifted them by the Egyptian envoy.

Despite signs pleading with visitors to cut it out – apparently it encourages the rats – a grand magnolia tree on the banks of the lake by a footbridge with lovely views is a spot where human, bird and rodent know to gather to feed and be fed. It is an undoubted thrill to have the bright green birds swoop down and sit calmly on your arm while they peck at whatever you have to offer.

Likewise, kneeling down and offering a little something to a nose-twitching, bushy-tailed little fellow is a pastime full of charm. There are regulars – those who idle away the time they have to spend in our green spaces, and strike up a relationship with the animals they see each day. They display a sense of ownership over the patch. Woe betide any occasional visitor who offers up a piece of their park cafe flapjack (amateurs!), and entices a parakeet or squirrel away from one of the serious feeders, who come equipped with high-grade healthy muesli for their furry and feathered chums.

There is, however, one parakeet and squirrel charmer who enjoys nothing more than showing off quite how tame his dependants are. He has something of a legendary status in the park, and your correspondent can vouch for this at first hand, having met him on the many occasions a parakeet feeding trip has been under taken by yours truly and child.

This human snack dispenser is in his 50s, and a very senior civil servant working in a stressful and high-powered job in Whitehall. He makes his way through St James’s every evening at 5.35 p.m., heading from a day of important government business, decked out in the requisite suit, mac and brolly. His Whitehall mandarin look has one important addition: in the deep pockets of his trench coat, he stores a seemingly bottomless supply of monkey nuts.

St James’s Park.

He interrupts his saunter home to his loving wife, children, dog, meat and two veg – and no doubt a pudding followed by slippers and crossword – to spend a pleasant forty-five minutes feeding families of squirrels. Generations of the bushy-tailed blighters have known and loved him, and are tame enough to clamber on his person as they feast on the supper he provides.

As he moves from London plane tree to London plane tree, he isn’t averse to sharing his squirrel-whispering skills with any wide-eyed child in the vicinity. He happily hands over a fistful of nuts and allows youngsters the thrill of having Nutkin clambering across them to gently feast.

LANDSEER’S LIONS AND LIVINGSTONE’S POST-PIGEON PLAZA

From St James’s, let’s head up The Mall, where urban myth says the road is designed to be an emergency runway for the RAF to land on and whisk Her Maj and hangers-on out of the city should we ever get round to revolting … and then on to Trafalgar Square, lying beautifully quiet, perhaps the first time in centuries that humans and pigeons have not run the place.

Ah, the pigeons of Trafalgar Square – no longer do they run the show, no longer do their sheer weight of numbers tip the urban balance from human to creature.

The Mall.

Trafalgar Square.

Pigeons and Trafalgar Square appear to have become a thing from the 1840s, about a decade after the square was laid out. The birds (Columba livia var) seemed to like the tall buildings around the square to roost on, and pigeons have a tendency to stay close to the nests they sprung from. They also form family units, with the cock and hen offering each other love and fidelity, through sickness and in health, no matter how gammy their legs may become. It meant the population of pigeons grew and grew – and that in turn attracted traders specialising in bird seed to take up residence. It wasn’t unusual – bird seed sellers were to be found across the city in any public space or pleasure park.

In 2001, it was estimated that 35,000 feral pigeons lived around and about the square, enjoying the lunches in return for a picture with a tourist. The then-mayor, Ken Livingstone, was livid at the fact it cost £140,000 a year to stop Nelson’s Column from being damaged by the birds’ acidic poo. He called them flying rats, cited research about the public health risk, and decided to withdraw the street trader licences issued to the stalls that sold bird food. It was a decision that caused huge controversy and nearly reached the High Court.

The anti-pigeon policy meant licences for street traders to sell seeds and grains were going to be withdrawn – prompting one of those David versus Goliath, Little Man versus the State-type stories that newspapers lighten a gloomy news day with. Seed seller Bernard Rayner, whose family had been happily selling seeds for nearly half a century, was joined by animal welfare activists to try and reverse the decision. Some feared the birds would starve to death, and brought sack loads of grain to scatter. It meant war, and the pigeons and their fanciers were not going to go quietly.

Westminster Council counter-attacked by moving a brigade of street cleaners in with giant vacuums to suck up stray bird food and employed pimply faced youths in oddly branded civic uniforms to shout at the birds – and those feeding them – through grating loudhailers.

On being told his licence, held since 1956, was not going to be renewed, Mr Rayner sought legal advice. The fate of the pigeons’ free lunch was in the balance. A showdown beckoned in front of a judge. Before the beaks could rule on feeding beaks, the GLA blinked and offered the Rayners an undisclosed amount of money in an out-of-court settlement. Whatever, the sum, it clearly wasn’t chicken (or pigeon) feed.

Today, there are still the remnants of the huge pigeon community – but naturalists say there are no more pigeons in the square per square foot than any place else in central London.

Still, there is a tooth and claw deterrent in situ. Hawks have become the go-to for councils hoping to keep feral pigeons away from civic centres, and if you’re lucky, you may well see one on patrol, winging its way past Nelson. If you’re squeamish, look away now. The hawks are trained and well fed, so they don’t need to hunt pigeons because they are hungry. Instead, if one gets to close, the hawk dives in and whips the poor thing’s head off, letting it tumble to the ground. It is said one unfortunate janitor each month draws the short straw and has to clamber out on to a fifth-storey ledge of a well-known block facing the square, and using a broom pole, dislodge a couple of headless carcasses.

The story of the friezes around the base of Nelson’s Column being made from the melted-down cannon of captured French ships during Napoleonic wars is well known. However, it isn’t such common knowledge that sculptor Edwin Landseer, who was commissioned to cast the four lions around the plinth, made sure his depiction was accurate when he’d never seen one on the flesh. He managed to source a dead lion from London Zoo and crated it back to his studio. From there, he knocked up the cast, racing against time as the poor creature’s cadaver began to decay and stink the place out.

Now on to St Martin’s Lane, first built by Robert Cecil, the 1st Earl of Salisbury, in 1610 and then added to by Sir Thomas Slaughter in the 1690s. It was known for two things: it was the centre of London’s horse tack industry, with shops selling bridles, saddles, reins, stirrups and assorted horsey bits and pieces, and the upper floors became a favoured residence for struggling artists, who could walk to the National Gallery for inspiration.

Later, furniture maker Thomas Chippendale was based there – and then the artist Hogarth set up an academy in the street.

HOGARTH AND THE ANGEL OF THE ROOKERIES

And with Hogarth in mind, it’s time we swing north-eastwards a little bit and head past Covent Garden to the Rookeries in St Giles, the scene of Hogarth’s seminal London illustrations, ‘Beer Street’ and ‘Gin Lane’. Drawn in 1751, ‘Beer Street’ depicted hearty Londoners supping good-for-you ales and being generally happy and well behaved, while ‘Gin Lane’ – based on what he had seen in the tenements of St Giles – depicted a society rotten through the imbibing of spirits.

St Giles was always seen as something of an unsavoury haunt, and fifty years after Hogarth had shone a revealing light (and Hawksmoor’s St George’s Church, built to oversee the St Giles parish and to offer some spiritual nourishment, had made little headway,) it was still a place of wanton debauchery.

It was in St Giles that the famous Billy Waters could be found. Billy, who had one leg, was a disabled busker and performer who was celebrated for his shows on the streets around Seven Dials. He was a former slave who had escaped captivity and joined the Royal Navy.

Billy Waters.

Billy served during the Napoleonic wars on HMS Ganymede, a well-armed frigate. The ship had been captured from the French by the Royal Navy (it was originally a 40-gun, 450-ton ship called the Hebe) in 1809. They intercepted the ship as it headed to the Caribbean with 600 barrels of flour on board. The Royal Navy renamed the ship HMS Ganymede and it went off to war under the Royal Ensign.

It was while Waters was serving on the ship that his life would be changed irrevocably: he had climbed to the top of the rigging before losing his grip and falling to the deck below. He was badly injured and had his leg amputated on the spot by the ship’s doctor. Somewhat remarkably, he survived the operation and returned to dry land. Down on his luck, he found lodgings in St Giles and found fame among Londoners, who liked his war hero story, his freed slave story and his agility and humour in performing a role. He was feted enough for Staffordshire potters to cast figurines in his likeness, and to be referenced in numerous books and plays.

But poor Billy was fated to have a trying end. Despite his talent, his hard work and his undoubtedly good relationship with his London crowd, Billy never made enough money from busking to be comfortable. As age-induced decrepitude crept in, he fell foul of the Poor Laws and ended his days in the St Giles Workhouse.

And on that note, we shall head into The Angel pub in St Giles High Street for well-earned refreshment. Or rather, we would if it was open!

The Angel pub.

The Angel has been there for centuries, and while the years have, of course, meant multiple refits and repairs, it retains a genuine sense of its longevity. A side passage, once used for horses to access the back stables, now leads you into a beer garden. Inside, it still has the moulded plaster ceilings, the old light fittings and the frosted windows and etched mirrors. The pressure on housing and the cost of living in central London has had a knock-on effect on pubs like The Angel. Sixty years ago, its regulars would have been people who lived or worked nearby – certainly, a sizeable proportion from within a 400m radius. Now West End pubs make up the trade lost from the changes in land use around them by hosting people from much further afield.

The Angel pub.

The Angel was in the midst of the infamous rookeries, the slums of St Giles, and no doubt saw life in all its glory. It was once the haunt of an infamous criminal, whose exploits gripped the working classes and to many was a folk hero. The Angel was cited in a 1741 Old Bailey trial of serial house-breaker and general rapscallion Thomas Ruby, whose exploits were the stuff Penny Dreadfuls loved at the time. Publican John Tucker of The Angel gave evidence to the court, explaining how Ruby had broken into the tavern and pilfered cash and stock. He was arrested in an advanced state of inebriation, snoring in the passageway for horses we first walked up, ending a long and prolific career as a burglar.

GOD GAVE ROCK AND ROLL TO YOU

Right, we’ve drained a pint in The Angel in St Giles High Street, a handy resting place on our stay-at-home stroll through the centre of town. Let us resume our locked-down ramblings, and walk off a couple of lunchtime beers.

Our first stop is Denmark Street, aka Tin Pan Alley, where your correspondent, aged 13, bought his first axe from Andy’s Guitar Shop on the corner.

The street is the original home of London’s live music scene and is the place musicians would gather to be hired for jobs, where recording studios churned out hits, where music publishers and composers plotted ear worms for all, where instruments were bought, sold and traded, and where Melody Maker and NME started their lives.

Regent Sounds Studio, Denmark Street, aka Tin Pan Alley.

We shall pause for a moment outside the former offices of Melody Maker, and spare a moment’s thought for one of the heaviest days at work surely any postman has ever endured.

In 1932, Louis Armstrong had travelled to London and done a two-week show at the Palladium that had knocked everyone for six. ‘His technical virtuosity and his rich, red hot personality gained many new converts to jazz music,’ wrote David Boulton in his 1959 book, Jazz in Britain.

Every one of his concerts was given national press coverage. When, a few months after his return to America, the Daily Express headlined on its front page an account of his death, it led to vanloads of hysterical letters from distressed and distraught fans to the Maker’s HQ. In those halcyon days of a nationalised and pre-email postal service, letters were delivered up to ten times a day. It left the magazine staff, along with the hard-working postie, in no doubt of the affection in which Armstrong was held.

Thankfully, the Express had made a critical error in their reportage. Armstrong was, of course, alive and kicking. He had simply been nipped in the leg by a depressed dog, ‘and rumour had magnified the event out of all proportion,’ wrote Boulton. Quite so.

Melody Maker focused on the type of music young intellectual types enjoyed: this was a period when the great historian Eric Hobsbawm wrote a jazz column for the New Statesman under the name Frances Newton, after the communist trumpeter who played with Billie Holiday, and the political cartoonist Wally ‘Trog’ Fawkes tried to balance his absolute genius at a draughtsman’s board with his equally world-class skill at blowing the clarinet. Trad Jazz was linked with polo neck-clad arty types whose duffel coats in the 100 Club cloakroom would have pockets stuffed with Lacan, Sartre, De Beauvoir and whatever else was cool on Bloomsbury campuses that term.

Perhaps because Melody Maker was seen as a more serious magazine than the New Musical Express, a more learned and intellectual tome as opposed to one happy to cover skiffle, it was through its pages that one of the country’s first artistic, anti-racist movements was born.

In the aftermath of the 1958 Notting Hill riots, in which Black Londoners were attacked by racists, Melody Maker’s editorial team were not going to stand idly by. In early September, just a week after the frightening disturbances, Melody Maker put on the front page a heartfelt letter signed by twenty-seven big names, ranging from Humphrey Lyttleton, Eric Sykes and Tommy Steele to Lonnie Donegan, Chris Barber, Peter Sellers, Harry Secombe, Tubby Hayes and Cleo Laine: ‘At a time when reason has given way to violence in parts of Britain, we, the people of all races in the world of entertainment, appeal to the public to reject racial discrimination in any shape or form …’

The Denmark Street publication would, a week later, print a two-page article by Frank Sinatra no less. His message to music fans was ‘you can’t hate and be happy’, and he threw his weight behind an anti-racist campaign prompted by the Melody Maker letter. It was a cause close to the magazine’s heart: years later, in 1975, they would print furious reactions to guitarist Eric Clapton’s nasty speech on stage in Birmingham, where he drunkenly spouted racist nonsense at the audience.

The stretch was known in 1930s and ’40s as a meeting point for big bands, the skiffle boom of the ’50s, the British blues explosion of the 1960s, ’70s punk and onwards – but today the browser can go even further back in time by stepping through the doors of the Early Music Shop. This wonderful establishment has a collection of traditional instruments, including the UKs biggest collection of recorders. Among the harps and harpsichords, the tabor drums and Baroque oboes, you can find hurdy-gurdies and the brilliantly bizarre-sounding ‘long-scale Medieval drum’, a cross between a finger piano, lute and tambourine. How much trade such a specialist shop does on a daily basis is one of those window shopper’s conundrums of time immemorial – who buys these things, we ask – but it is yet another reason to love and cherish city-dwelling alongside others who clearly have a need for such things.

While in Denmark Street, it would be churlish to miss the chance to name drop horrendously – after all, this is a thoroughfare that has borne witness to the musical development of the Sex Pistols (a possible oxymoron, you may say), David Bowie, The Stones, The Kinks, Led Zep and countless others in a host of dimly lit basement studios. It was where Elton John and Bernie Taupin wrote their early hits, where Lionel Bart of Oliver! fame had an office, and where Paul Simon was told by a music publisher that his songs ‘Homeward Bound’ and ‘The Sound of Silence’ were nice but not marketable.

But while these guys are comfortable bestsellers, let us spare a thought for a man who has carried the torch for this musical Mecca, ensured the street remained relevant and added greatly to its reputation over the years.

Andy Preston spent his youth working in Cumbria as an engineer and a musical instrument restorer. In the late 1960s, he headed to London to seek work repairing and restoring guitars. He headed down Tin Pan Alley to see what opportunities there might be to fix, mend and spruce up axes in need of TLC.

Walking along Denmark Street, he found a corner shop owned by a Greek family, selling groceries and whatnot. ‘I went in to buy an apple, and there was a husband and wife working behind the counter,’ he recalled. ‘I asked them if they knew anywhere round here I could set up a guitar workshop. “A-ha”, they said.’

The couple showed him the cellar beneath the thin, four-storey terrace. When Andy first went down the narrow, winding staircase, he had to stoop because the ceiling was so low. Buried in the floor was a pickaxe. The owners had decided to deepen the cellar and set up a club for other Greek Cypriot émigrés, and made a half-hearted attempt to get the place useable and ship-shape by digging out a couple of feet and lowering the floor. Instead, Andy set up his workbench and a Tin Pan Alley institution was born.

As his reputation spread, he employed other guitar makers and technicians. ‘I soon had a team of five of us working in the basement,’ he recalls.

But when the smell of glue, polish, paint and resin began to take over the ground-floor store, the shopkeeper said he didn’t believe the two businesses were compatible and offered Andy his lease for the whole building.

Andy’s had a shop on the ground and upper floors, and in the nooks and crannies you would find wood being worked, electrics being fixed, necks varnished, strings strung. Andy’s was painted in an ad hoc yet striking manner – a colour scheme of bright yellow and red, slopped on by staff and possibly from a mix and match selection of half-used pots. It all added to the charm.

Performers at Andy’s Guitar Shop and the 12 Bar Club.

But there was more to come – it was from this humble workshop that a legendary music venue was born. Andy’s team of craftsman were all, unsurprisingly, rather handy at playing the instruments they were fixing.

‘When we shut up the shop each night, we would go to this place called the Diamond Dive Bar, on the corner of Tottenham Court Road,’ Andy remembered. ‘We used to go there for a jam and drink. Lots of customers would come into hear us play. We were all jamming there and then one day the landlord said, out the blue: “I am fed up with you all!” and kicked us out. We were stunned – he’d made good money out of us.’

A grumpy landlord meant they were looking for somewhere else to play. Next door to Andy’s was a blacksmith’s forge. Its bellows had long stopped huffing, its anvil no longer clanged and its furnace had not known warmth for decades. It had been used by the Covent Garden health food restaurant Food for Thought as a store room, and a kip house for the owner’s daughter and her friend.

When they moved out, Andy’s amp repair department moved in – and soon a small stage had been built along a wall, a PA set up and the jams began again.

‘It attracted customers – they’d come in to hear it,’ recalls Andy. ‘It was like hey, this is like a little club, so why not open the doors. People started coming in – not one or two, but lots and lots.’

The official opening night of the 12 Bar Club saw Andy rustle up ten buskers he knew who worked pitches in the West End. Andy and buskers had a long-term relationship. Andy would save strings he had taken off guitars, clean them, sort them out and then give them away to skint street performers for free. He arranged for all ten to meet on Charing Cross Road and all launch into ‘Hey Mr Tambourine Man’ as they led a parade to the new 12 Bar.

At first, food and drink came in an unconventional way. Staff would take an order, and then nip out of a back door and across the alleyway to the kitchens of a Greek restaurant. They’d return with a tray and charge a little on top for the hassle of popping across an alley.

‘It really took off,’ recalls Andy. ‘Eventually we had to move the amps we were repairing out and make it in to a proper club.’

Its draw was such that when successful Swedish businessman Lars Ericsson found himself inside, he sought Andy out and offered to back him.

‘This guy came in and said I love the blues,’ recalls Andy.

The pair formed a partnership, and the club expanded, taking space from a comic book shop next door, a Chinese restaurant, and running music studios above the venue.

‘It was a whole colony of music,’ Andy states.

Awards followed, and big names made a point of turning up. When headliners would be at the Astoria, their road crew would make a point of bringing musicians over to the 12 Bar to unwind.

‘We would get really famous people turning up and they’d get on stage on play – they’d do an unplugged number. You’d get this great atmosphere – ordinary, amateur players sitting in and playing alongside very famous musicians. It was quite an oddball place.’

Among those who entertained were Adele, The Libertines and Bert Jensch. But it wasn’t about the names who came in through the door – or the unknowns who cut their teeth in the eighty-capacity gig room.