3,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Sandstone Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

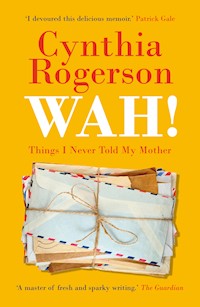

Shortlisted for the 2022 Highland Book Prize Cynthia's mother is dying. Often. Travelling between her home in Scotland and California, as she spends time at her mother's bedside Cynthia recalls her youthful adventures: living in a squat, train-hopping, hitchhiking and all the other things she never told her mother. 'A master of fresh and sparky writing.' The Guardian

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Praise for Wah!

‘Wah! is as poignant as it is hilarious, and that is saying something. Everyone with a mother should read this book.’

Louisa Young

‘I have devoured Wah! the delicious memoir from Cynthia Rogerson. Perfect wet weather reading for anyone with a parent crumbling long distance or anyone who was far naughtier than said parent ever knew . . .’

Patrick Gale

‘A memoir about joy in the shadow of grief, Wah! is both moving and funny, with a wonderfully light touch – completely charming.’

Tim Dowling

‘Wah! seems at first to be a tragicomic account of a dying mother who won’t die. But gradually, with Rogerson’s distinctive fusion of empathetic warmth and unrestrained frankness, it encompasses the entire scope of life from childhood to old age, and all the different kinds of love.’

Michel Faber

‘Cynthia Rogerson doesn’t spare the horses of intimacy; she tells it like it is and she tells it all. Wah is witty, rich in revelation, and elegantly written. Her style owes something to Richard Brautigan – she’s from California after all – and this only increases my delight.’

Chris Stewart

‘A selfie of a tearaway with a real writer in control of the chaos. A wonderful and courageous book.’

Bernard MacLaverty

‘Wah! Is witty, compassionate, playful, scarily honest and emotionally accurate. It does that rare, liberating thing, being funny about pain without diminishing either the humour or the hurt.’

Andrew Greig

‘Novelist Cynthia Rogerson kept a few secrets from her late mother about her free-spirited past. In more ways than one, this sparkling memoir is a revelation.’

David Robinson

‘A rich, lyrical text that will show the tears at the heart of things.’

Richard Holloway

‘In this scintillating memoir, covering six decades and moving between California and the Scottish Highlands, Cynthia Rogerson delivers another wonderful book. Episodes from a conventional childhood, wilder adolescence and breakaway early twenties and her older self’s commentary on them are laugh-aloud funny, poignant, rude, wicked, shallow and profound – sometimes all on the same page.’

James Robertson

‘A marvellous read. It’s searingly, almost wincingly honest yet at the same time teases the reader by embroidering over the line between memoir and fiction. Rogerson is especially good at portraying the tenderness and confusion of pain and loss, the complex tangle of feelings we have for our loved ones, and her wisecracks skewer even the bleakest moments.’

Lesley Glaister

Cynthia Rogerson (aka Addison Jones) grew up in California. She is the author of six novels and a collection of short stories. She won the V.S.Pritchett Prize in 2008, and her short stories have been widely broadcast and anthologised. I Love You Goodbye was shortlisted for Best Scottish Novel in 2011 and translated into five languages. She holds a Royal Literary Fund Fellowship.

By the same author

Upstairs in the Tent

Love Letters from My Death Bed

I Love You Goodbye

Stepping Out

If I Touched the Earth

Wait for Me, Jack

First published in Great Britain in 2022 by

Sandstone Press Ltd

PO Box 41

Muir of Ord

IV6 7YX

Scotland

www.sandstonepress.com

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

Copyright © Cynthia Rogerson 2022

Editor: Nicola Torch

The moral right of Cynthia Rogerson to be recognised as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

ebook ISBN: 9781913207748

Cover design by Stuart Brill

Typeset by Biblichor Ltd, Edinburgh

In memory of my mother, Barbara Jones

1929–2018

Writing is really a matter of coming to terms with your own squalor.

Frederic Raphael

When a writer is born into a family, the family is finished.

Czesław Miłosz

Contents

Warning

Wah!

South Van Ness

Cashmere

Keys

Three Kisses

I Don’t Know You

Something Fishy

Monsters

Last Rites

I Miss You

George is Dead

Going to Mexico

Death, It is Here!

Cool

Sisters

They Weren’t Pretty

Two Cans of Dogfood

Powder Blue Pantsuit

Come Home Now!

In Orbit

Get Rid of It

A Year is a Circle

God is God

Priscilla the Pig

Hospice Doghouse

SS Lurline

Love Letters

Our Lady of Solitude

Scoot In

Hi Ho Silver Lining

No Touching His Things!

Magic is Real

Oh, Baloney!

Silent Night

Joy of Cooking

A Long Enough Courtship

You Bet

By Lamp Light

This is Nuts

Ave Maria

Stop Worrying about the Fish

Epigraph and Acknowledgements

Warning

When my brother was born, we got a puppy. In my mind these were equal events and I had two brothers. A few years later, when it was my turn to Show and Tell at St Philomena’s nursery, I brought a picture of our dog and said he could talk. That, in fact, we talked all the time.

Sister Rose sighed and shook her head.

‘Show and Tell is not for fibbing, Cynthia. You have to tell the truth,’ she said.

The other children sniggered. I blushed but didn’t cry. Then I told a story in which my dog did not talk. He retrieved sticks, rolled over and scared burglars away. They were all lies – but good lies – and everyone clapped when I finished.

In my defence now, and by way of introducing this book, I would say this: maybe the dog talked.

Wah!

The summer my mother started dying in earnest, it stopped raining in Scotland. Our well ran dry and we took showers at my daughter’s house. Wildfires broke out and no one knew what to do. All this distracted me from my mother’s impending death in San Rafael, California – but it also seemed to emphasise it. Like her dying, it was both shocking and natural. What did we expect? Most people on the planet had already suffered because of climate change, but it was hard not to take personally. Tempting to see the drought as a result of Mom dying, as if in her death throes, her panic was drying up clouds. Or maybe the heatwave was California coming to me at last, summoned by decades of homesickness. Maybe it had missed me too, sought me everywhere till it finally found me hiding in the Scottish Highlands. I was tired and tended to read meaning into everything.

My first deathbed visit was in August.

‘The end, it is here. You must come,’ said her caregiver on the phone.

Ateca (pronounced Atetha) was a Fijian woman, sixty-four years old – the same age as me – and whenever she told me to do something, I did it. Her voice was gruff and staccato. When she watched football on television, she sat hunched forward, legs apart, and shouted like a man. Run, run, run, you beauty! Or more often: No, no, no! What’s the matter with you?

I arrived to find my mother in a hospital bed next to her own bed. My sister explained that’s what hospice means in California. Hospice comes to you.

‘Mom, I’m here!’

‘How did you get here?’

‘Flew.’

‘You flew! What do you mean?’ This was a genuine question. She wasn’t capable – had never been capable – of sarcasm. With dementia, she was even more literal-minded.

‘I flew in an airplane to come and see you.’

‘That is . . . charming!’

It turned out that at the end, not only did you lose your independence, you didn’t even get to pick your own words. You just got what you got. My mother got charming, delightful, creepy, correct and wah! She used wah! a lot, by itself, with a capital letter and an exclamation mark. Basically her Wah! meant I have no fucking idea what to say. It was never said without a smile, so I think there was also an element of defiance. I have no fucking idea what to say and I don’t give a shit. She never swore, but that didn’t mean she didn’t think in swears.

Her stock of phrases included That’s perfectly normal, Are you all right, He or she is an odd duck, Que sera sera, and So be it. Oh, and I love you, of course. Now and then she’d come out with French words. Moi? covered all sorts of occasions, though was suspiciously close to Wah! which could be confusing. C’est la vie! came in handy sometimes. Lately she’d begun to ask the time a lot, enunciating every syllable. Excuse me, can you please tell me the time? As if she was late for an appointment and asking a stranger in a public place. She didn’t learn any Fijian words, even though she heard Ateca on the phone all day. Not even bula. All of Ateca’s conversations began and ended with bula-bula. Every time I heard that, an old Motown song would start up in my head. I didn’t know which one, but that didn’t matter. She’s my baby, bula-bula, bula-bula, bula-bula.

I lowered my face to Mom’s hospital bed and kissed her. She gave me three hard kisses back. I noted she still didn’t smell like an old lady. She smelled of Clinique night cream and she looked pretty. Somehow, she’d skipped the unattractive side of old age and leapfrogged straight into the home run.

‘See you in the morning, Mom. Goodnight.’

‘God bless you,’ she said, which was odd because we were the kind of Catholics who got embarrassed when people talked about God. Maybe Ateca, who was Pentecostal, had rubbed off on her.

It must have been confusing for my mother to see her own bed but not be in it. Or maybe sometimes she did see her old self in her old life, wearing that Lanz nightgown with the top button missing. Her husband not dead, but snoring next to her, making that loud popping noise like a rubber ball bouncing down the street.

‘Hey, it’s me,’ she might have whispered to herself. ‘Wake up. You won’t believe what’s going to happen to you.’

But then her own words would waken her, and she’d just be her old lady self in a hospital bed looking at her empty marital bed. She might notice it was much more neatly made than she’d ever managed and think: Wah!

The next day, when I popped into her bedroom to say good morning, her face lit up as if she hadn’t seen me for a hundred years. Her famous red-lipstick smile, her teeth miraculously still white, still straight.

‘Is it really you? All the way from Scotland?’

‘Yup,’ I said, feeling goofily happy.

‘You’re so beautiful! Come here, you.’ She stretched her arms out towards me and we hugged.

Oh, I was going to miss this kind of appreciation. My mother loved me more than anyone loved me, even my father who’d set out to woo me and in large part succeeded. She loved me more than I loved her. I never loved my mother enough to tell her what was really going on in my life. In the early years, sometimes months went by when I didn’t even bother sending a postcard. I used to tell myself I was protecting her, but the truth was less noble. I was a daddy’s girl and kept her at a distance. I probably made my mother cry sometimes. Made the person who loved me more than anyone else in the world loved me, cry. So perhaps it wasn’t ironic that at her deathbed I had an urge to record the truth of my past. As if the child who’d been careless with her abundance of motherly love was now insisting – stamping her feet! – on making up for lost time. Memories lurked everywhere I looked – had been lurking for decades – but they lurked no longer. They stepped into the light and said in a slightly patronising voice: Yeah, you really did this and said that dumb thing, right here, in this exact spot.

After breakfast with my mother and Ateca, I sat at my dead father’s desk, opened my laptop and began to write. I began with my father throwing his glass of wine at me because I’d had sex with the boy down the street whom he’d expressly forbidden me to see. Had I really been that stupid? That bad? And then I remembered moving in with a man who lived inside his foam furniture factory. He’d picked me up hitch-hiking, which was the main way I met boys in those days. I studied my right thumb, recalling how I wriggled it at the side of the road fifty years ago. I’d loved not knowing which of the passing cars would stop, not knowing where I’d be in an hour. It seemed I could be my truest self with strangers.

Wah, wah, wah! I thought, sick of myself suddenly.

My wah! was not my mother’s wah! It was more like the wah in Peanuts, when a grown-up tries to talk but all that Charlie Brown hears is wah-wah-wah. And then, because my darling mother would soon be gone, I had a silent little sob for myself. Which was, I suppose, another kind of wah. But still not my mother’s.

South Van Ness

Eighteen years old

California, 1971

I had a room in an old woman’s basement that fall. I had to enter through the garage, and the room was dark and pine-panelled. There was a tiny bathroom but no kitchen. That was fine. I’d burned down the kitchen in the last place I’d rented a room. Clearly, I was not to be trusted in kitchens. There’d been Sufi dancers in that other place, and they’d refused to be angry with me even though the fire had destroyed all their vegan cooking equipment. I couldn’t handle that. I needed punishment.

A few months ago, when I was still living at home in San Rafael, I’d slept with the new neighbour down the street whom my father had specifically told me to avoid. I’d knocked on his door and asked if he had any rolling papers. Within fifteen minutes, we were both naked and he was walking around the house with me pinioned on him, my legs around his back, arms around his neck. I was not petite so he must have been athletic. His beard exfoliated my face. I went back home, transparently fornicated, and my father’s face got very red. Then he threw his wine at my face and said:

‘Get out!’

I marched straight out of the house and hitch-hiked to a friend’s house. The wine was white, and as soon as it dried there was no sign he’d even thrown it. Within a day, I’d found the Sufi house and moved out of my old bedroom. In front of my tearful five-year-old sister and my envious sixteen-year-old brother, I walked out of my childhood home clutching a duffle bag full of clothes and shoes and books I considered good. I don’t remember my mother in this. She may have been there. She was self-effacing and undemanding but loved us continually. She was probably there in the hall, watching me head off into the unknown. I have no idea what she felt. Perhaps she was asking herself if she was supposed to cling to me, beg me not to go. She was too shy to do anything so demonstrative, but she might have pictured it just the same. My father had removed himself proudly to the garage during my exit. My house, my rules. He had a point. I was a brat.

In my new life ten miles away, I started junior college and worked as a waitress in an old folks’ home, and hitch-hiked everywhere. I got C minuses at college that first semester and I was a terrible waitress. Hitch-hiking was the only thing I was good at. I’d perfected it the previous summer in Europe, where I thumbed, occasionally on the wrong side of the road. It was a revelation I could go anywhere for free. Aside from being raped in the back of a van in France, it was fun and I made lots of friends. I met a man who called himself Morris the Minnow in Galway and camped with him on Inishmore. I formed a trio of hitchers with a Jewish woman from New York and a home counties boy called Julian, and we hitched from Paris, right across the Channel on a car ferry and up to his parents’ ancestral pile in Hampshire. My address book was crammed with new addresses, where I was assured a place to sleep if I was in the area. I’d not made a success of high school, but I was quite good at standing by the road waggling my thumb at drivers. I’d finally found my gift.

One day, after my waitress shift, I was picked up by a tall man in a white van. I was on my way to San Francisco to sit in Café Trieste and feel soulful. It was a very big van, comfortable and clean. The back was full of chunks of foam.

‘What’s all the foam for?’

‘I manufacture furniture,’ he explained. When I stared blankly, he continued. ‘I make furniture, beds and sofas mainly, using foam.’

He smiled with very white teeth and had a pretty face, like a woman. His blue eyes seemed honest and trustworthy. No beard – he looked like he might not be able to grow a decent one. His hair was strawberry blond and hung to his shoulders, not straight but not curly either. Fluffy. He looked old, maybe thirty.

‘Cool,’ I said. ‘Do you have any rolling papers?’ That was my only line.

We ended up at his factory on South Van Ness and 15th Street, which was near the freeway overpass. No houses on this block – just warehouses and flop houses. A fifteen-minute walk from Union Square, it was a side of the city I’d not seen. We entered and immediately there were stairs – steep and dark. I didn’t hesitate a second but was aware this was a point at which caution would be appropriate. I kept taking my emotional temperature to see if I was frightened. At the top, he showed me where he slept – the factory was also his home. The walls of his bedroom were comprised entirely of yellow foam somehow attached to the structure of the building. The door was a wedge of foam that you had to fold back and then slide your body through. Inside was a piece of foam on the floor, made up into a bed. There were some clothes neatly folded in a corner on the floor, which was also foam. It was a padded cell with a single bulb hanging from the ceiling, but oddly cosy. Maybe it was the yellowness and the way it smelled of Johnson’s baby powder. Outside the room was the kitchen. This was a wooden plank over two saw horses, on which sat a can opener and dozens of cans of tuna and sweetcorn, a few plates, bowls and cups. Cutlery stuck out of an empty sweetcorn can. There was also a jumbo-size box of Corn Flakes and some boxes of powdered milk.

‘No stove?’

‘Raw food is better for you.’

‘No sink?’

‘There’s one in the bathroom,’ he said and smiled kindly, as if it was a silly question. Why would any house need more than one sink?

All this time, he was kind of dancing around me on the balls of his feet, his long skinny legs propelling him in a bouncy way. He seemed delighted I was there, albeit bewildered. Nothing he did set off alarms. I liked his minimalism. For foreplay, he showed me the factory beyond his bedroom. There was a rough-hewn balcony which we stood on, and below on the ground floor was a veritable swimming pool of foam. Then he climbed over the railing and leapt down. I followed. Falling on so much foam was like falling into cake. It made me giggle. The sex wasn’t memorable, but I was still so immature. It was like smoking a joint but not knowing how to inhale, which I’d done for years. Later, he dropped me off at an onramp for 101 north and I was back in my pine-panelled basement room within an hour.

I kept failing at college. Maybe my mother was wrong and I wasn’t a genius. I was always too tired to study and my salary wasn’t stretching as far as I thought it would. I was working full-time and I didn’t see how I could make more money. I liked the idea of a philosophy or an English degree but wasn’t prepared to make many sacrifices to get one.

I didn’t have a boyfriend. I wasn’t sure Foam Man would describe himself as my boyfriend, though we’d met up three more times. There was a boy I met at college who showed me how to give a blow job one day. We did it in my pine-panelled room. It was hard to keep quiet, but we had to try because the old lady upstairs could throw me out. I hid how disgusted I was, because he didn’t seem to think it was disgusting at all. Besides, it seemed a useful life skill to acquire.

‘Move your hand like this, just at the base,’ he whispered.

‘Like this?’ I whispered back.

‘Yeah. But you’re not sucking. You’re slurping. Suck.’

‘Like this?’

‘Ouch! Goddammit.’

I gagged at one point. I was C minus at blow jobs too. I kept clearing dirty tables, daydreaming in classes, and hitching home regularly to see my family. The tension had evaporated within days of my leaving, and now they were always glad to see me. Even my father. We enjoyed each other’s conversation too much to stay alienated. I was waiting for my life to begin, I guess. I was making lots of mistakes and not having as much fun as most people my age seemed to be having. Life was generally a little flat. I was waiting to know who I would be, but mainly I think I was waiting for someone to love.

One night in my narrow bed, I was listening to the radio and the new Harry Nilsson song came on. It was called ‘Without You’ and was on the radio all the time that fall. His reedy voice was perfect for a song about being left. A curious thing happened as I listened. My chest filled up and I wasn’t tired any more. I pictured myself as both the sad-eyed leaver and the broken-hearted one left behind. The song was corny, but also painful because it seemed to be saying something true. Lovers sometimes lacked the power to hang on to loved ones, and worse – sometimes loved ones left, even when they knew they were loved.

Harry Nilsson kept crooning that he couldn’t live, if living was without someone. Had I ever loved anyone that much? Had I ever been loved that much? No, I had not. Did I want to? Yes, it turned out I did. But who to pour this love into, and who to be the beloved of? Why, Foam Man of course! He wasn’t perfect, but he was the only one I could think of. I fixed on his face, his shoulders, his bouncy way of walking. I got up, got dressed and left the house. It was late, maybe 10.30pm. I was exploding with resolution. It felt great to be following an impulse and not analysing anything. Thinking, I decided, was overrated. I walked to the onramp for 101 south and stuck out my thumb. I wore my usual outfit – hip-hugging bell-bottoms, a peasant blouse (no bra), and a corduroy jacket that had belonged to my father.

I quickly got a lift to the city, and then stuck out my thumb again on Lombard. The air was cool and the foghorn was mourning away. Standing at a bus stop with my thumb out, I felt vestiges of fear while watching a group of men loiter outside a corner bar. One of the men kept hawking and spitting, and another kept laughing like a hyena. Finally, a car pulled over and the driver rolled down his window:

‘Hey, you working?’

‘Working? No,’ I said, puzzled, and got in his car.

He turned and stared at me, and I waited for him to say something else.

‘Are you going up to Van Ness?’ I finally asked. ‘I need a lift to 15th and South Van Ness.’

‘Oh, what the hell,’ he suddenly said, and pulled out into traffic.

My swollen heart had waned a little but when I heard his footsteps coming down, it began to flutter again. I’d never experienced emotion as a physical object, like a thick liquid in my upper chest. Was this love? I decided it was, and also that I wouldn’t require more than this chance to love someone. Being a beloved would be the icing on the cake.

‘Jesus! What are you doing here? It’s past midnight.’

‘Yeah, well. I just suddenly wanted to see you.’ There was an awkward pause, so I added, ‘I was in the neighbourhood.’

I couldn’t articulate the romance of my impulse. It would sound impossibly juvenile in spoken words. But surely he’d recognise the dramatic gesture for what it was? He was so much older – he must know all about dramatic gestures.

‘Huh. Well, come on up and get warm. I’ve got some peppermint tea. Then I’ve got some paperwork to do.’

Peppermint tea? Where was the wordless embrace? The sense of rightness?

But within a month, I’d moved out of the pine-panelled basement and into the foam factory. I dropped out of college, but still hitched to the old folks’ home to waitress till I had enough money to fly back to Europe. If I wasn’t going to get a degree or a career or a beloved, I might as well travel. From the beginning, when I moved in with Foam Man, it was understood. He offered no mushy talk and neither did I. My midnight visit was never referred to. This was my base camp while I saved up to travel. A temporary base. He didn’t ask for money and I didn’t offer it. I didn’t even pay for my share of our daily tuna fish. We never drank, though sometimes shared a joint at bedtime. He had such a long lanky body, it was nice to feel entirely wrapped in it. We tended to read in bed, more than anything else.

Then the day came.

‘I’ve got my ticket.’

‘Yeah?’

‘I leave next weekend.’

‘Wonderful. You must be excited.’

This was exactly how he was supposed to behave, but my heart sank. The preferred response, I realised with sickening clarity, was: Please don’t go. I willed Foam Man to say those words, or any version of that sentiment. My throat became sore with unshed tears as the time of departure grew near. It was all tragic and unnecessary. I felt my life teeter between completely different paths: the known and the unknown. But it wasn’t really teetering. It was timidly waiting for choice to be removed. All he had to say was please stay, and I would stay. Like the lyrics that had propelled me out of my bed six months earlier and sent me to his door, I now had the eyes with hidden sorrow, and I was leaving. If he would only notice and burst into song. I can’t live, if living is without you.

But he didn’t, and I left.

Cashmere

The days passed, hot cloudless days, and my mother kept not dying. I never forgot my purpose in being there, but I was easily distracted and lacked the attention span required for sustained anxiety. I wanted to be practical, so I cleared out the hall closets. Old sleeping bags, Christmas wrapping paper, my sister’s dollhouse furniture seemed unimportant now so I gave them away. Early in the mornings when it was cooler, I took long walks to the levee or China Camp. I read a book of my dead father’s – his bookplate still glued in place. Sometimes I sat in Andy’s café and phoned my sister. All these activities felt like deathbed commercial breaks. Satisfying in their way, but also heightened because they were sandwiched between my mother’s dying moments.

I had many roles at home in Scotland. Here, I was just the daughter of a dying woman. A woman I’d never bothered getting to know, mostly because I thought I knew her already. She’d made me, but who the hell was she? I began a list.

Things I Learned from My Mother:

• Ants are okay. If your See’s candy box is invaded by them, just wipe the ants off and give it as a gift.

• If you get tired of that long line of ants snaking across your kitchen counter, spray them with Windex.

• If your husband accuses you of being paranoid when you suspect him of infidelity, then he is certainly messing around with another woman.

• If your husband is handsome, sexy, funny and a hedonist, be certain he will not be kind, patient or loyal.

• Cider vinegar diluted in warm water makes your hair shiny.

Every morning I crept to her bedroom and peeked to see if her chest was still rising and falling. She had so many things wrong with her: bladder cancer, multiple sclerosis, an under-active thyroid, vascular dementia. The hospice doctor had said it was only a matter of days, maybe hours, but true to form, my mother was doing her own thing. She napped on and off all day, and every evening cleaned her dinner plate with gusto. If she’d noticed Death loitering around the foot of her bed, she’d probably have said: You’re creepy. Scoot!

It was her eighty-seventh birthday in a few days. What to give someone who had everything but time? See’s candy was an obvious choice, but I wanted to buy something luxurious and beautiful – after all, it was her last birthday. As I perused the racks of cashmeres, I dithered. Was it dumb to spend $200 on something she might never wear, or if she did, might end up covered in drooled fruit juice? In the end I bought a cheap fleece, machine washable and soft. When I got home after being away an hour, her face lit up like it always did.

‘Is it really you? It’s you!’

‘Yup, it’s me,’ I said, noting the curious happiness her smile always gave me – a kind of happiness so predictable, I’d not always recognised it as such. Had even, at times, felt repulsed by it. I may not have told her much about my life, nevertheless she’d witnessed a multitude of my childish humiliations. My dearth of dates in high school was a particular sore spot. How could I respect someone who had such poor taste as to love me?

‘All the way from Scotland. Scotland!’ She said this as if Scotland was the moon.

‘Yup. Scotland.’

That night, after I’d watched The Sound of Music with Mom, I began a story about my first marriage ending. We’d been as amateur at divorce as we’d been at courting. I hadn’t laughed much at the time, but now we seemed hilarious. It made me wonder what else I was taking years to see in the correct perspective. Maybe everything. It was fun to tell the truth for a change in my writing. But the truth about truth, I discovered, was there was always more than one version. First I felt one way about that marriage, and the next hour I remembered it differently. Maybe numbers were the only things you couldn’t mess with. Calendar dates, amounts of money, phone numbers.

On the morning of Mom’s birthday, without thinking very hard, I took the cheap fleece back to the store and exchanged it for a cashmere sweater. I was a wreck. I needed to give this deathbed birthday the best shot I could, no matter how unlikely my effort would be appreciated. And in case that makes me sound generous, a small voice was whispering the cashmere would be mine soon anyway.

Keys

Fifty years old

Scotland, 2003

After my first husband moved out, keys stopped working for me. They wouldn’t turn in locks. They wouldn’t go in locks in the first place. Even the checkout lady at Tesco found her key stuck in the till while serving me. I was always losing keys, but this felt a different level of dysfunction.

It’d begun as a healthy break-up. After twenty years, we told ourselves we no longer loved each other. Not properly. We’d gone to Amsterdam to save our marriage, but all we did was discuss how exciting life would be once we’d parted. We were so proud of ourselves. We got drunk in a tiny bar near the train station. Over three nights, it had become our place. We sat in the same chairs by the window, ordered the same drinks and watched the cyclists almost get hit by cars over and over. Sometimes cyclists would have to steady themselves by holding on to the roof of a passing car after a previous car had caused them to wobble. Sometimes drivers would speed up to zoom around a cyclist, narrowly miss a pedestrian, then slam on their brakes to avoid a head-on collision with another car. No cyclist wore a helmet. It was riveting.

‘What will we tell the kids?’ I asked.

‘The truth.’

‘Okay. But which truth?’ He hadn’t shaved in a few days, and it was quite annoying how nice he looked.

‘Is there more than one?’

‘Of course.’ I was thinking of ways I could come out of this looking all right.

‘What do you think we should tell them?’

‘I don’t know. We could sit them all down and tell them we love them, that it’s nothing to do with them, but we’re going to live apart for a while.’

‘For a while?’

‘Sure. It will be forever, but we could let them figure that out in time. Not hit them with the whole shebang right away.’

‘You always sentimentalise things.’

‘I do not.’ I was deeply insulted.

‘But you do. Your writing too.’

‘Like you’ve ever read anything I’ve written.’

‘There you go. Painting me as a selfish moron because it makes a good story.’

I huffed and drank in silence for a minute or two. He bought more drinks, and by the time he got back to our table I wasn’t angry.

‘I’ve got an idea,’ he said.

‘What about?’

‘We could tell them you’re a lesbian.’

Pause while it sank in.

‘You genius!’ I admitted. We toasted the idea, which struck us as hilarious because it was so naughty to lie to our darlings. Not to mention hijacking gayness to let me off the hook. I’d been so ashamed of my behaviour, but suddenly, sitting in that bar with the suicidal cyclists outside and naked women behind picture windows lining the street, it seemed a mere peccadillo. You couldn’t even call it an affair – it was more of an accident. No one seeing us would suspect we were planning our divorce. And that was funny too. We nearly peed ourselves laughing. Then we went back to the hotel, crawled under the sheets and had sex for the first time in ages.

Once we were back home, we got on with the business of parting. We wrote lists of things to do, but we did them in the wrong order. My husband gleefully began his single life while still living with me. He joined several dating sites. Well, why not? We were being so sensible, so open. But we forgot to tell the kids.

‘Hey, Dad,’ said our eldest one day, when he ran into his father downtown. ‘You off somewhere nice?’

‘Yep. Got a date, actually.’

‘A date?’ He thought it was a joke, but not very funny.

‘Yeah.’

‘With who?’

‘Oh, you don’t know yet, do you? Me and your mum, we’ve split up.’

‘What?’

‘Yup. Sorry about that. Got to dash.’

The other three found out the next evening, when we were all eating dinner. I’d made macaroni and cheese, a huge bowlful because it was everyone’s favourite. We had a guest, the son of a friend in California who’d sent him to live with us because he’d dropped out of high school and she didn’t know what to do with him. He wore his jeans rapper style, with the crotch at his knees and the crack of his bum clearly visible. He also wore mirror sunglasses while sitting at the kitchen table. It was not great timing, having a house guest as we were breaking up, but it also seemed entirely normal. On the surface it was a typical family dinner – bickering, spilled milk, giggling, eating.

‘Is Inspector Morse on tonight?’ I asked my husband. He always remembered these things.

‘Yes. But I won’t be here.’

‘Oh. Okay.’ It was hard to swallow my macaroni, but I pretended I didn’t care.

‘Can you pass the salad? And also iron my blue shirt?’ he asked.

‘For tonight?’ We were talking in lowered voices.

‘Yeah.’

‘Seeing her again already?’ I couldn’t help myself.

He gave me a look I’d never seen on his face before. Joyful guilt. It was disorienting. What had I created?

‘No, no. I’m seeing someone else tonight. Siobhan from Clachnaharry.’

There was something about the way he stretched out those syllables, and the way the dog was under the table licking the floor, and the cat was scratching the sofa again, and the way the younger two were flinging bits of bread at each other. I’d begun pouring juice from the jug into glasses, but I found myself throwing the jug-full in his face. There was a moment’s silence at the table. The kids’ faces were probably frightened, but I didn’t notice. I wasn’t very good at being angry – I lacked practice. Come to think of it, I wasn’t very good at breaking up for the same reason. This was my first.

‘Are you insane?’ he asked, standing up with juice dripping from his face. His voice sounded young and tearful.

‘You’re insane!’ I threw back, like a five-year-old. ‘And I am not going to iron your fucking blue shirt.’

Then it dissolved into slapstick. I told him to leave and he didn’t. I pushed him out the door and locked it. He shouted to open it and I refused. He appeared at all the windows, banging and shouting. No one let him in. Sometime during the commotion, while we were all racing to barricade the windows and doors, I explained to the kids we were splitting up, so it wasn’t exactly wrong that their dad was going on a date. The fact of our impending divorce was now a rider on the much bigger drama of Daddy trying to break into his own house. Our guest rushed enthusiastically to every door and window my husband appeared in, shouting in a silly voice: No, no, you can’t come in! Not by the hair of my chinny chin chin! My kids thought this was hysterical, but I suspect they also knew something terrible was afoot. And all along, under everything, was a sense of déjà vu. Of course! Hadn’t he shoved me out of the house when he’d discovered my peccadillo six months ago? Oh, we were terrible parents, playing out our wars in front of the children. But when did other parents conduct these things? Our children were omnipresent.

Later that night, of course, he was allowed in and we pretended all was normal. He must have cancelled his date because he watched Inspector Morse with me. I remember not being able to follow the plot. Two days passed, in which I pretended nothing irreversible had happened yet and soon this exhausting game would be over.

Then he left. Or, to be precise, he moved a few feet away.

I came home from Tesco to find he’d taken our camping stove and set up camp in our extension. He’d nailed up the connecting door. It was glass, so for privacy and soundproofing, he’d piled up photo albums against it. Also old encyclopaedias, pillows and sleeping bags. There was an outside door and he kept his bit of the house locked, even when he was in it sometimes. Things were not panning out as I’d thought they would. He was supposed to disappear into his new life, and keep paying for me and the kids to stay in our home. I was supposed to be fighting off gorgeous men knocking on my door day and night.

The reality was hearing the clickety-clack of high heels on the other side of the wall. I didn’t own heels. I was already taller than him, and didn’t like to make him feel small. Or I didn’t like to feel tall. I never figured that one out. The reality was sneaking a look at his profiles on dating sites, and raging because he pretended to read literature. It was watching him go to salsa classes when he’d never danced in my presence, even when I was dancing like a mad thing in front of him. It was watching him lose weight and wear fashionable clothes, noticing he now had contact lenses and his grey hair had become brown. Without me, he had become the very man I’d wanted him to be.

I was cutting up onions for spaghetti sauce one day, when suddenly there he was, walking past the kitchen window, chatting happily with some big-boobed woman. Chatting! I used to yearn for some easy small talk, some banter. And yes, as a small-boobed woman, I took the big boobs personally. Taunted by tits.

But I had not wanted this man, I reminded myself. I’d plotted to lose him. So why was I furious? I couldn’t shake off the notion he was mine, even if I had no use for him. Logic wasn’t helpful. I even missed our fights – the ones we had over and over because we couldn’t resolve them. Like the car key fight. I’d once (maybe twice, but certainly not more than four times) locked the kids in the car with the keys still in the ignition. It was distressing, especially if it was a hot day. I would smile like a maniac through the window, pretending Mommy was just playing a silly game until the nice policeman opened the door. Their Daddy never left the keys in the car or the car unlocked, which would be all right if we were not in the car at the same time. Travelling as a family – to the beach for a picnic, for example – could be disastrous, especially if I was driving. The first time we were locked out of our car, we called a locksmith – but after that we learned how to break in with a coat hanger, usually borrowed from a nearby house. It happened at least three times a year. We got to be very good and briefly considered a career of car thieving. Our usual routine:

‘The car’s locked,’ I would tell him. ‘Where are the keys?’

‘You drove.’

‘I know. But the doors are locked.’

‘I know. I locked them.’

‘We’re in the middle of nowhere.’ This said slowly, with contempt. ‘You really think there’s thieves in the area?’

‘You left the keys in the car again, didn’t you.’ Not a question.

Near the end, I locked the keys in the car on purpose. I wanted to live through our weird ritual one more time. But it wasn’t as much fun as I’d hoped, as if that part of my life was already sealed off from me. Ironically, now I was the only adult in charge, I never left the keys in the car and I always locked it. I ceased relaxing on a deep level – I was shocked to realise how much I’d depended on my husband to keep us all safe. And if I was driving alone, I developed a habit of pulling into certain lay-bys for a scheduled weep. I looked forward to it. A lament for my lost imperfect life, though I wasn’t sure if I was pining for him or the family unit.

The fracture of his leaving opened the door to all sorts of other fractures, like a spreading fault line. My beautiful sixteen-year-old daughter began telling me to fuck off regularly, as in:

‘Good morning, honey, you look nice today.’

‘Fuck off.’