7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

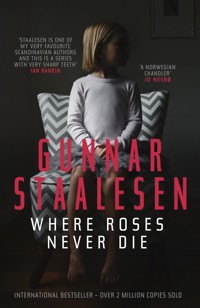

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Varg Veum

- Sprache: Englisch

The 25-year-old case of a missing girl sees Varg Veum dig deep into the past to find her kidnapper, as the secrets and lies of a tiny community threaten everything … Gunnar Staalesen's award-winning, international bestselling Varg Veum series continues in this chilling Nordic Noir thriller. ***WINNER of the Petrona Award for Best Scandinavian Crime Novel of the Year*** 'Mature and captivating' Herald Scotland 'One of the finest Nordic novelists – in the tradition of Henning Mankell' Barry Forshaw, Independent 'Masterful pacing' Publishers Weekly _________________ September 1977. Mette Misvær, a three-year-old girl disappears without trace from the sandpit outside her home. Her tiny, close middle-class community in the tranquil suburb of Nordas is devastated, but their enquiries and the police produce nothing. Curtains twitch, suspicions are raised, but Mette is never found. Almost 25 years later, as the expiry date for the statute of limitations draws near, Mette's mother approaches PI Varg Veum, in a last, desperate attempt to find out what happened to her daughter. As Veum starts to dig, he uncovers an intricate web of secrets, lies and shocking events that have been methodically concealed. When another brutal incident takes place, a pattern begins to emerge… Shocking, unsettling and full of extraordinary twists and turns, Where Roses Never Die reaffirms Gunnar Staalesen as one of the world's foremost thriller writers. _________________ Praise for Gunnar Staalesen 'There is a world-weary existential sadness that hangs over his central detective. The prose is stripped back and simple … deep emotion bubbling under the surface – the real turmoil of the characters' lives just under the surface for the reader to intuit, rather than have it spelled out for them' Doug Johnstone, The Big Issue 'Gunnar Staalesen is one of my very favourite Scandinavian authors. Operating out of Bergen in Norway, his private eye, Varg Veum, is a complex but engaging anti-hero. Varg means "wolf " in Norwegian, and this is a series with very sharp teeth' Ian Rankin 'Staalesen continually reminds us he is one of the finest of Nordic novelists' Financial Times 'Staalesen does a masterful job of exposing the worst of Norwegian society in this highly disturbing entry' Publishers Weekly 'The Varg Veum series is more concerned with character and motivation than spectacle, and it's in the quieter scenes that the real drama lies' Herald Scotland 'Every inch the equal of his Nordic confreres Henning Mankell and Jo Nesbo' Independent 'With an expositional style that is all but invisible, Staalesen masterfully compels us from the first pages … If you're a fan of Varg Veum, this is not to be missed, and if you're new to the series, this is one of the best ones. You're encouraged to jump right in, even if the Norwegian names can be a bit confusing to follow' Crime Fiction Lover 'With short, smart, darkly punchy chapters ... a provocative and gripping read' LoveReading 'Haunting, dark and totally noir, a great read' New Books Magazine 'An upmarket Philip Marlowe' Maxim Jakubowski, The Bookseller 'Razor-edged Scandinavian crime fiction at its finest' Quentin Bates

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 418

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

PRAISE FOR GUNNAR STAALESEN

‘Gunnar Staalesen is one of my very favourite Scandinavian authors. Operating out of Bergen in Norway, his private eye, Varg Veum, is a complex but engaging anti-hero. Varg means “wolf” in Norwegian, and this is a series with very sharp teeth’ Ian Rankin

‘The Norwegian Chandler’ Jo Nesbø

Razor-edged Scandinavian crime fiction at its finest’ Quentin Bates

‘Not many books hook you in the first chapter – this one did, and never let go!’ Mari Hannah

‘With its exploration of family dynamics and the complex web of human behaviour, Staalesen’s novel echoes the great California author Ross MacDonald’s Lew Archer mysteries. There are some incredible set-pieces including a botched act of terrorism that has frightening consequences, but the Varg Veum series is more concerned with character and motivation than spectacle, and it’s in the quieter scenes that the real drama lies’ Russel McLean Herald Scotland

‘There is a world-weary existential sadness that hangs over his central detective. The prose is stripped back and simple … deep emotion bubbling under the surface – the real turmoil of the characters’ lives just under the surface for the reader to intuit, rather than have it spelled out for them’ Doug Johnstone, The Big Issue

‘Norwegian master Staalesen is an author who eschews police procedural narratives for noirish private eye pieces … Staalesen dislikes Scandinavian parochial in his writing, and continues to work – bravely, some would say – in a traditional US-style genre, drawing on such writers as the late Ross MacDonald. Nevertheless, he is a contemporary writer; there is some abrasive Scandicrime social commentary here’ Barry Forshaw, Financial Times

‘In Staalesen’s deft yet unhurried style, numerous plot threads are interwoven around the kernel of suspense established in the beginning … this masterful first-person narrative is very much character-driven, as Varg’s tenacious personality drives his destiny and the events that lead up to the surprise-laden finale’ Crime Fiction Lover

‘Staalesen’s greatest strength is the quality of his writing. The incidental asides and observations are wonderful and elevate the book from a straightforward murder investigation into something more substantial’ Sarah J. Ward, Crime Pieces

‘Staalesen’s mastery of pacing enables him to develop his characters in a leisurely way without sacrificing tension and suspense’ Publishers Weekly

‘Gunnar Staalesen was writing suspenseful and socially conscious Nordic Noir long before any of today’s Swedish crime writers had managed to put together a single book page … one of Norway’s most skillful storytellers’ Johan Theorin

‘An upmarket Philip Marlowe’ Maxim Jakubowski, The Bookseller

‘The prose is richly detailed, the plot enthused with social and environmental commentary while never diminishing in interest or pace, the dialogue natural and convincing and the supporting characters all bristle with life. A multi-layered, engrossing and skilfully written novel; there’s not an excess word’ Tony Hill, Mumbling About Music

‘There is a strong social message within the narrative which is at times chilling, always gripping and with a few perfectly placed twists and turns that make it more addictive the further you get into it’ Liz Loves Books

‘With his cynical and witty asides, an unflinching attitude to those who would thwart his investigations, and his dogged moral determination, Veum is a hugely likeable and vivid character’ Raven Crime Reads

‘The characters and settings are brilliantly drawn and the novel pulls you in so that you keep turning the pages and race to the conclusion … This isn’t just a crime novel that you pick up, read and then cast aside. It is a life that you have been given a glimpse of so that you want to see more’ Live Many Lives

‘Staalesen proves why he is one of the best storytellers alive with a deft touch and no wasted words; he is like a sniper who carefully chooses his target before he takes aim’ Atticus Finch

‘The plot is compelling, with new intrigues unfolding as each page is turned … a distinctive and welcome addition to the crime fiction genre’ Jackie Law, Never Imitate

‘A well-paced, thrilling plot, with the usual topical social concerns we have come to expect from Staalesen’s confident pen…’ Finding Time To Write

‘We Shall Inherit the Wind brings together great characterisation, a fast-paced plot and an exceptional social conscience … The beauty of Staalesen’s writing and thinking is in the richness of interpretations on offer: poignant love story, murder investigation, essay on human nature and conscience, or tale of passion and revenge’ Ewa Sherman, EuroCrime

Where Roses Never Die

GUNNAR STAALESEN

Translated from the Norwegian by Don Bartlett

To our good friend, Gary Pulsifer (1957–2016). We miss him already. This English edition of Where the Roses Never Die is dedicated to his memory. Thanks for everything, Gary!

Don, Gunnar and Karen

Contents

1

There are days in your life when you are barely present, and today was one of those. I was sitting behind my desk, half-cut and half-asleep, when I heard a shot from the other side of Vågen, the bay in Bergen. Not long afterwards I heard the first police sirens, although there was no reason to assume this would ever be a case that might involve me. By the time I had eventually staggered to my feet and made it to the window, it was all over.

Reading the newspapers the following day, I found out most of what had gone on, the rest I learned in dribs and drabs.

Afterwards they were universally referred to as the Shell Suit Robbers. There were just two customers in the exclusive jewellery shop in Bryggen when, at 15.23 on Friday, 7th December 2001, the door swung open and three heavily armed individuals, wearing balaclavas and dressed in what are informally known as BBQ suits, burst into the premises.

The two customers, an older woman and a younger one, cowered in the corner. In addition to the customers there were two female assistants in the shop. The owner was in the back room. He’d hardly had time to look up before one robber was standing in the doorway and pointing a sawn-off shotgun at him. He said in what was supposed to be English: ‘Don’t move yourself! The first person who presses an alarm button are shot!’

One of the robbers took up a position by the front door with an automatic weapon hanging down at thigh-height and kept lookout. The third opened a big bag, gave it to the assistant in front of the display cabinets and pointed a gun at her. He spoke in English too: ‘Fill up!’

The assistant objected: ‘They’re locked!’

‘Unlock!’

‘But I’ll have to get…’ She motioned to the counter.

‘Move, move, move!’

She cast a glance at the other assistant, who nodded resigned agreement. Then she opened a drawer behind the counter, took out a bunch of keys and went back to the display cabinets.

The robber in front of her directed a glance at the door: ‘Everything OK?’

The robber posted there nodded mutely.

The robber by the office door intoned the same message: ‘Move!’

The jewellery-shop owner shouted: ‘You have no idea what you’re doing! All our items are registered internationally. No one will buy the most expensive pieces.’

‘Shut up!’ The robber pointed to a safe in the wall. ‘Open.’

‘I haven’t got…’

The robber rushed forward and held the rifle to his head. ‘Open. If you…’

Sweat poured from the jeweller’s forehead. ‘Yes, alright … Don’t…’ He swivelled the office chair and rolled it towards the safe. ‘I just have to … the code.’ He put a finger to his brow to show how hard he was trying to remember.

‘You know. Don’t make me to laugh.’

‘Yes, but when I’m nervous…’

‘You soon have even more reason to be nervous if you…’

The robber tapped the safe door with the weapon, and the owner stretched out his right hand and with trembling fingers started to turn the lock and enter the code.

Inside the shop the older of the two assistants opened a display cabinet. She took out the watches one by one and carefully placed them in the bag, so slowly that the robber impatiently pushed her aside and began to scoop watches of all price ranges into the bag while shouting orders: ‘Open the other cabinets! And you…’ He looked at the assistant by the counter. ‘All the drawers! At the bottom also.’

In the back room, the safe was open. The robber brutally shoved the jeweller out of the way and emptied the safe contents on to the work table. Papers and documents were sent flying to the floor. With a triumphant flourish, he held up a box of eight diamond-studded watches. The owner eyed him with an expression of despair.

The robber stuffed the box into a shoulder bag. Then he grabbed a wad of notes from the back of the safe and in they went too. ‘Black money, eh?’

‘Cash reserves,’ the jeweller mumbled bitterly.

The robber backed towards the door and glanced out into the shop. ‘Everything OK?’

The robber by the front door nodded. The other one was busy emptying the drawers from the counter. ‘Just a moment.’

The robber who had been in the back room swung the sawn-off shotgun from the jeweller, to the two customers and finally to the older of the two assistants. ‘Don’t you move yourselves. The first person who presses the alarm button are shot.’ He was still standing in the doorway with a view of the back room. ‘Finished?’ he said to the man behind the counter.

‘That’s it now.’

‘Good.’

The robber by the front door leaned on the handle and glanced across the shop for instructions. The robber in the back room nodded, the front door was opened and with their weapons at the ready they dashed out.

That was when it happened.

None of the four women saw what went wrong. Other witnesses, on the pavement and around the quay on the other side of the street, could only relay fragments of what they thought they had observed. A passing motorist was convinced he had seen everything, ‘from the corner of his eye’, as he later put it.

As the robbers were making their getaway they must have collided with a man on the pavement. The man yelled, there was a second or two of silence, then further words were exchanged and a shot was fired, the man was hurled backwards and crashed on to the pavement, blood spurting from his chest, near his heart.

The three robbers hotfooted it across the street, sprinted along the harbour front and threw the bags into a small, white plastic boat waiting for them by the quay. An engine roared and the little boat, foam spraying over its bows, hurtled across Vågen, where eye-witnesses saw it disappear around the tip of Nordnes peninsula soon afterwards.

In the shop, the owner appeared from the back-room door. With sagging shoulders he said: ‘I’ve rung the alarm.’

The younger of the two customers was the next to speak.

‘That one by the door … I’m pretty sure … that one was a woman.’

Five minutes later the first police officers arrived, alerted by radio that a full-scale search was under way in the whole district.

The case was to become something of a mystery. I followed it only desultorily in the newspapers, and on radio and TV; first of all it was breaking news, then it was relegated to the back pages. There was more interest locally than nationally, but here too it wound up in semi-obscurity, as do most unsolved crimes, until something new is revealed and they become front-page news again.

The greatest mystery was how the robbers could have vanished. After the boat had powered round Nordnes peninsula it was never seen again. At the time in question, on a cold, blustery December day, there were not many people out walking in Nordnes Park, and no witnesses came forward, either from there or anywhere else along Puddefjorden. It did seem as if the thieves had literally vanished into thin air.

The police searched all the quays from Georgenes Verft, the shipyard, and beyond, past Nøstet, Dokken and Møhlenpris, as far as Solheimsviken and from there to the Lyreneset promontory in Laksevåg, without turning up anything of any value. They went through the list of stolen boats in the region with a toothcomb. The ones they eventually found, they crossed off the list, but as late as March, three months after the robbery, there were still some that had not been located. It was the same story with the list of stolen cars. The general assumption was that the robbers must have come ashore somewhere in Nordnes or Laksevåg, transferred the booty to a car and driven off. Under such circumstances thieves often used a stolen vehicle and later set fire to it, after switching to their own cars. But no cars had been torched, to the police’s knowledge, during that period – neither on the 7th December nor the following days.

What made the case especially serious was the murder. After a couple of days the dead man’s name was released. Nils Bringeland was my age, fifty-nine years old, ran a little company in Bryggen and from all the indications seemed to have been no more than a casual passer-by. He left behind a partner and three children, two of them from an earlier marriage.

The case received broad media coverage, locally and nationally, for the first few days after the robbery. The shop owner, Bernhard Schmidt, was interviewed widely. He said his business had been run on the same premises for three generations since his grandfather, Wilhelm Schmidt, set it up from scratch in 1912. Bernhard Schmidt took the shop over from his father in 1965. There had been minor thefts, and in 1973 there was an attempted break-in through the backyard, but this was the first time in the company’s history that they had experienced anything as dramatic as a robbery. He wouldn’t divulge to the press the value of the items that had been stolen, but other sources speculated the figure lay somewhere between five hundred thousand and a million Norwegian kroner, perhaps even more. Neither the police nor the insurance company wished to comment on this aspect of the case.

The two female shop assistants were also interviewed, anonymously, but they had nothing of any importance to add, apart from the trauma of the experience. The younger of the two customers, Liv Grethe Heggvoll, appeared in the press with her full name. She and her mother had been in the shop looking for a fiftieth-birthday present, and they were as shocked as the shop employees by what they had witnessed. Asked by journalists whether she had noticed anything special about the robbers, she answered they had spoken English with what she considered was a Norwegian, or maybe an Eastern European, accent. ‘What’s more,’ she added, ‘I’m positive one of them was a woman.’

This information was later taken up by the police. They said it was too early to know whether this might have been an itinerant gang of professional robbers, but they were keeping all their avenues of inquiry open. As for the possibility of a woman being involved, they had no comment to make. The conspicuous get-ups – the so-called ‘BBQ shell suits’ – were discussed in several newspapers. The three suits were identical in colour and design: dark green with white stripes down the sleeves. Pictures of a similar style were everywhere, although the police refused to comment on whether they’d had any response from the general public.

As the investigation ground to a halt there was less and less to read about the case. There was no reason for me to give it a moment’s thought. I had my own daily demons to fight at that time. I was on the longest and darkest marathon of my life, and it was still a long way to the tape.

2

The assignment I received on that Monday in March would perhaps turn out to be the most important I’d ever had, not least for my own sake. It was the first sign of light at the end of a tunnel that was much longer than I cared to admit.

The three years that had passed since Karin died had been like an endless wandering on the seabed. I had seen the most incredible creatures, some of them so frightening I had woken up bathed in sweat every time one appeared in my dreams. Enormous octopuses stretched out their long tentacles towards me, but they never managed to hold on to me. Monstrous monkfish forced me into jagged nooks and crannies, placed a knee on my crotch and emptied my pockets of valuables. Tiny fish floated by enticingly, their tails in the air, but were gone before I had managed to reach out a hand to grab them. A rare sea rose opened for me, drew me in and afterwards extracted its levy in the form of unpleasant after-effects and dwindling self-respect.

It was a life in darkness; I had difficulty seeing clearly down there. The only thing that kept me going was the consolation I found in all the bottles I stumbled over. None of them lay around long enough for green algae to form.

The millennium had passed and Doomsday had not arrived. Nostradamus had been wrong; so had St John and those who still believed in his revelations. Not even the IT experts who had prophesied the Y2K crisis had been proved right. No computer systems collapsed, the world continued on its wayward course with no further changes to our everyday lives, except that we had to write a ‘2’ at the beginning of the year.

As for me, I spent the last days of 1999 delving into a hundred-year-old murder mystery, and when New Year’s Eve came, like so many other Bergensians, I walked half-way up a mountain in pouring rain and watched the New Year rockets disappear from sight in the low cloud cover, never, it seemed, to return to earth again. Afterwards I trudged down to my flat in Telthussmauet, where I celebrated the arrival of a new millennium in the company of a bottle of aquavit.

The first two years of the new century passed more or less unnoticed, apart from the dramatic events of 11th September 2001 on the eastern seaboard of America. New Year 2002 didn’t seem to be ringing in any great changes either, not in my life nor in the world beyond. It had just become even more burdensome to fly. An old lady with a heart defect and a tube of ointment in her hand luggage would create longer queues at the security check, and if she couldn’t produce ID she was denied access to her plane. Apart from that, most things were the same.

The woman who came to see me that Monday in March was of the gentle sort. She tapped several times on the waiting-room door, then I heard her open it and venture in. I had plenty of time to screw on the top, put the bottle into a desk drawer, drain the glass, rinse it in the sink and place it tidily on the shelf under the mirror, before turning, walking to the door between the waiting room and the office, opening it wide, swaying in the doorway and saying, ‘Yes?’

She met my eyes with trepidation. ‘Are you … Veum?’

I nodded, stepped aside and ushered her in: ‘This way.’

She was about my age, perhaps a bit younger, but I definitely put her in the late fifties. Her hair was lank, and it was some weeks since she had been to the hairdresser’s. The grey was clearly visible at the roots of her hair, in the parting on the left of her head. Her choice of clothing didn’t suggest she was out to make a winning first impression, either. She was wearing a classic, moss-green windproof jacket, brown trousers and flat shoes. The red in her scarf was the only colour to brighten her appearance. In her hand she was carrying a suede bag big enough to contain whatever she might need in terms of everyday accessories. Her skin was pale, her nose small, across the bridge a patch of freckles was just visible, and her face had a sad air about it, which immediately revealed she was struggling with a problem, perhaps several. But most of the people who came to visit me were. Why else would they come?

She glanced around shyly as she stepped into the office. I held out my hand and introduced myself properly. She told me her name: Maja Misvær.

I directed her to the client’s chair. No one else apart from me had sat there for many weeks. I walked round the desk, slumped down into the swivel chair, unfurled the gentlest expression I could muster and asked: ‘How can I help you?’

She looked at me gloomily, as if the word help didn’t exist in her world. I could see my own face in hers, as though I was gazing into a mirror, the way it must have appeared to others over the last three years. Six months after Karin’s death I had walked in the funeral cortege for my old school friend, Paul Finckel. One of my oldest friends, and best sources of information in Bergen’s newspaper world, he had switched off his computer for good, without saving the contents for posterity. A newly employed colleague had taken it over before the corpse was cold. I felt my own demise had edged a step closer, like autumn announcing its arrival one frosty night in September. One by one they were leaving us, my old classmates. Soon there would only be a handful of us left. In the end, there would be none.

‘D-do you remember a little girl called Mette?’

At first I didn’t understand what she was talking about. ‘Mette? I don’t know that I…’

‘She went missing in September 1977.’

Then a light came on. ‘Ah, you mean that Mette.’

Two Bergen children had gone missing in the 1970s. Both disappearances had shaken the local community and had initially kept the media busy, before being put on a back burner. In fact, I had helped to solve one of the cases, the 1979 one, some eight years later. The other case had never, to my knowledge, been cleared up. It became known as ‘The Mette Case’.

She nodded.

‘But I don’t quite remember … when was it you said?’

‘17th September 1977.’

I did some swift mental arithmetic: 1987, 1997, 2002. In six months the case would be time-barred, if someone had killed her, that is, and anything else was barely conceivable, bearing in mind how thorough the investigation had been. ‘And Mette, she was…?’

‘Yes, she is my daughter.’

I noted the change of tense. ‘Could you … It’s so long ago … Could you refresh my memory about … the details?’

She heaved a sigh, but nodded assent. ‘I can try. What I remember of it and what … I know.’

3

The barely three-year-old Mette Misvær disappeared from her home in Solstølvegen in Nordås on Saturday 17th September, in the short space of time between twelve o’clock and a quarter past.

‘I was at home, busy with housework. Mette was sitting in a sandpit right outside the kitchen window. I kept peering out at regular intervals, but when she disappeared I was busy taking clothes out of the washing machine and putting them in the tumble dryer. As soon as I emerged from the laundry room I went to the window to check on Mette…’

When she didn’t see her, at first she wasn’t initially that concerned. The house they lived in formed part of a yard with four other houses, and it was not at all unusual for children to move around this protected area, where cars only came in on very special occasions.

‘I thought that … perhaps some of the children from the other houses were outside playing and Mette had toddled over to join them…’

She leaned over towards the window, but still couldn’t see Mette anywhere. Then she went from the kitchen to the front door and into the yard. She looked everywhere. ‘No children anywhere, neither Mette nor anyone else.’

Then she went to the gate in the wooden fence on to Solstølvegen. The gate was closed. She opened it and walked out. Nothing. In the estate further to the west there were some adults walking around and pointing, and in the street below there were a couple of cars parked. There was nothing else to see.

Then she began to get seriously worried. She ran back into the yard, went to the first house on the left and rang the bell. The husband, Tor Fylling, came to the door. He was on his own. His wife and children had gone to town. He hadn’t seen Mette. ‘She must be at Else and Eivind’s place,’ he added. ‘Try there.’

She nodded and hurried over to the neighbours’ house. She rang the bell several times, but no one answered. ‘It turned out later that the family had been away for the whole weekend, in their cabin on Holsnøy.’

She ran past the next house. They didn’t have any children. Now there was only one house left, wall to wall with their own. ‘I said to myself – why hadn’t I gone there first? They had Janne, who was the same age as Mette.’

But when the mother opened the door she had Janne in her arms. She listened to Maja with alarm. ‘Mette? No. Yes, I saw her half an hour ago, from the window, she was sitting outside and playing. But … can’t you find her?’

Maja’s neighbour, Randi Hagenberg, became more and more agitated with every question she asked. ‘Have you looked in the garages?’

‘No. I didn’t think of that.’

‘Let’s look now then. I’ll come with you!’ She called to her husband: ‘Nils, can you take Janne?’

Together, they dashed over to the garages, which faced Solstøvegen, east of the five houses. One garage door was open. It belonged to the family who had gone to town. They went inside and scoured the area, but Mette was nowhere to be seen. The other four garage doors were locked. They tried all four handles, but none of them budged.

Now Maja Misvær could feel panic seizing her. Without thinking she ran twenty to thirty metres down the road in one direction, shouting her daughter’s name, stopped to listen, and when she heard nothing, turned round and ran in the opposite direction and repeated the action. ‘All at once I couldn’t breathe. My heart was pounding so hard I could feel my pulse up here, in my throat, and I could hear blood rushing through my body like a … like an echo in my eardrums.’

‘We’ve got to phone the police,’ Randi Hagenberg said.

‘Yes,’ Maja answered as tears flickered in front of her eyes, so suddenly that her vision was affected and she almost lost her balance. She took a few quick steps to the side and supported herself on the fence.

‘But when I looked at the sandpit again … it was then I realised. There was her teddy bear, abandoned in the sand, and, deep down, I knew … she took it everywhere. She would never have left it behind!’

‘No?’

‘No…’

While they waited for the police they ran around the district, calling Mette’s name. Many of the other neighbours came out and assisted with the search. Some went to talk to people on the estate, but no one had seen a little girl.

Someone had contacted Mette’s father, Truls Misvær, who was at a football training session with the older of their two children, six-yearold Håkon. He drove back home as fast as he could. Soon he had joined the others in their increasingly larger circles around the hilly area, looking for the missing girl.

When the police arrived they immediately set up an organised search and radioed information to their colleagues. Not long afterwards the story was on the news: Small girl missing from her home in Solstøvegen in Nordås.

The police drew a blank. Tiny Mette Misvær was never found.

The investigation escalated over the first few days. From being a straightforward missing-person case it was quickly upgraded to a potential crime. With none of the enquiries bearing fruit and Mette still missing the day after, the system went into overdrive.

All the neighbours were summoned to interviews. None of them had observed anything at all, except for Randi Hagenberg, who was able to confirm that she had seen Mette sitting and playing in the sandpit immediately before she disappeared.

Adults from the estate were also brought in for questioning. A couple of them thought they had seen a car stop outside the gate. But it had been too far away for them to say anything definite about the make of car or any distinguishing characteristics. One of them thought it had been black, another dark grey. A four-door, dark-grey or black saloon was what the police had to go on when they alerted all the patrol cars and gave a description. Nothing came of this search either.

According to the press, everyone on the child sex offender register in Bergen, later in the whole country, had their movements on the day in question charted and recorded, but the results were as unproductive as everything else. The case remained unsolved.

Now that was almost twenty-five years ago. If Mette Misvær had been allowed to grow up she would be a woman of twenty-eight. The likelihood was she was lying in an unmarked grave somewhere, gone for ever.

After Maja had finished talking she sat staring despondently at her lap. She mumbled a word I didn’t catch.

‘What was that?’ I asked carefully.

‘Rose. She was my little rose. But I didn’t pay enough attention and someone picked her.’

‘And now you’d like to…?’

She raised her face and looked me in the eye. ‘I’d like you to find her. I want you to find out what happened. Before it’s too late. Before everyone who might know anything has also gone.’

4

After a short pause she said: ‘I’d like to show you … where she disappeared.’

‘Do you still live there?’

She nodded. ‘I always think … that I have to be there for when she returns. So that she’ll never have to go round looking for me.’

‘But … I rather think we should wait until tomorrow.’

‘Have you got something else to do?’

‘Yes, today I have.’ I couldn’t tell her the truth. Getting behind a car wheel was simply out of the question. The morning pick-me-up had been too potent. The taste of caraway was still on my tongue.

‘But,’ I added, ‘I can still spend some of today getting my head round the case. Do you remember who you dealt with in the police back then?’

She sighed. ‘It was … we never really got on.’

‘Really?’

‘His name was…’ For the first time she showed something redolent of a smile, but it soon vanished. ‘It was a curious name for such a large man.’

I had a suspicion. ‘And the name was…?’

‘Muus. Inspector Muus.’

Now it was my turn to sigh. ‘You never really got on, you say?’

‘No, he seemed so … brusque, in my opinion. As though it were my fault Mette … People should take better care of their children, he said once.’ She looked into the distance with a sad expression on her face. ‘No, I never did get on with him.’

‘But there must have been others?’

‘Yes, of course. There were many who were very sympathetic. A couple of women officers, amongst others. Cecilie Lyngmo, I think that was the name of one of them.’

‘Yes, I knew both Muus and Cecilie. But they’ve both left the force now.’

‘Yes…’

I had jotted down her address while she was talking. ‘This neighbourhood … Solstølvegen, that’s in Nordås, isn’t it?’

‘Yes, with a view of Nordåsvatnet bay. At that time it was brand new and almost completely isolated. It was Terje Torbeinsvik’s first big project.’ When I didn’t react to the name she added: ‘The architect. I don’t know if you remember. He was married to Vibeke Waaler, the actress.’

‘Yes, I remember her. But she’s in Oslo now, isn’t she?’

‘Yes. They got divorced. She’s at the National Theatre.’

‘And what do you mean by his “first big project”?’

‘It’s called Solstølen Co-op; there are only five houses, around a yard. It was designed as an environmental project; it was supposed to merge into the landscape and be capable of adapting to modern systems, mostly energy-saving ones, as they came on the market. Terje still lives up there and he’s still developing new projects. The next one is aimed at harnessing ground heat – if that means anything to you. With the aid of deep boreholes.’

‘Yes, I’ve read about it. It definitely sounds better than wind turbines.’

‘Even then there was digging going on all around us. And now … now we still have a wonderful location, but the view isn’t quite what it was. New buildings have gone up between us and the water, and in the nature reserve where we searched for Mette there has also been some building.’

‘Are there many people living in the co-op now who were there then?’

‘Yes, most have been happy there despite what happened to Mette. Only one of the houses has changed hands. In several of the others there have been divorces. That’s just the way it was then, in the seventies and eighties.’

I nodded quietly. I had been there myself.

‘And the children have moved out, of course. Now there are only children in two of the houses.’

‘Does that mean …? What about you? You and your husband?’

‘Yes, we … Two years after Mette went missing we split up. It was simply too much to bear. Håkon stayed with Truls. I would have been happy to look after him, but … all I thought about was Mette. It was as though I couldn’t concentrate on any other children except her. Anyway, Håkon and Truls had so much in common. Football. Håkon even played for FC Brann for a few seasons.’

‘I see.’ I tried to recall his name in a football context, but couldn’t.

‘Afterwards I lived alone.’ She said this in a way that suggested it hadn’t been a loss, more the confirmation of a fact.

‘So you haven’t met anyone?’

‘No.’

‘And what’s your relationship with … your ex-husband and his family? Håkon?’

She hesitated. ‘Håkon came to see me regularly, of course, but … He’s alone too, even though he’s over thirty now. And he’s moved away. I haven’t spoken to Truls for several years. He…’

‘Yes?’

‘He could never forgive me. After all, I was supposed to be looking after her. It was as though he blamed me for all that happened.’

‘I understand.’

‘And he was right of course! It was my fault. If you had any idea how many years afterwards I went out searching for her…’

‘You mean…’

‘Yes, I couldn’t sit still in the evening, I had to go out and look, even if it was absolutely pointless. As though she had only got lost and stayed away for two or three years. But I couldn’t control it. My grief was so immense, my agitation so unmanageable that it’s marked the rest of my life, every single day, every single night.’

I looked at her. There was something genuinely desperate about her features, something that reflected what she told me so much more clearly than the words she used: the dreadful experience the little mite’s disappearance must have been … and for her never to re-appear.

I considered my options. ‘Would you say there’s any point me talking to the others who lived in the co-op when Mette went missing?’

She gave me a blank look. ‘The police were so thorough. There was no reason to believe…’ Suddenly she clutched at her throat and coughed, as though there was something stuck. ‘I mean … how could any of them … we were such a tight-knit group.’

‘Would it be OK if I went out to see you tomorrow?’

She nodded.

‘In which case, would you mind making me a list of the people who lived there then? I mean … as some of the families have broken up … If I’m going to talk to them I’ll try to get in touch with as many as possible.’

‘Alright, I’ll do my best. I mean … yes, I’ll do that. It’s not that difficult.’

‘OK.’ I got up.

She didn’t move. ‘I was wondering if…’

‘Yes?’

‘How much will this cost?’

I pulled out a drawer from the desk and passed her a sheet of paper. ‘This is a list of my charges. It might look a bit overwhelming, but once I’ve started, I work efficiently and … there may be a discount.’

She perused the sheet and folded it without a further word. She was, like me, prepared for the worst. At least that was some comfort. She didn’t have great expectations, either.

She stood up, and it struck me that I hadn’t offered her anything to drink. I was a bad host these days.

‘So you’ll come tomorrow?’

I nodded. ‘Around ten, is that convenient?’

She said yes and I accompanied her to the door. That was as far as my social graces stretched now.

I went back into my office, reached for the beaker on the shelf, opened the lowest desk drawer to the left, took out the bottle and filled the glass half-full. The aquavit was clear and shiny, like tears emanating from a deep well. There was more where that came from.

I toasted an imaginary adversary. Dankert Muus, of all people. The inspector who had hoped to see me again in hell now would have to see me alive. I didn’t ring to warn him I was coming. That would have been too much of a risk.

5

With a pensionable age of around sixty it was not unusual for police officers who had completed their service in the force to take on other jobs, some of them on the margins of the same branch. Some were employed by insurance companies, some as investigators. Some worked as bailiffs in the law courts. Some worked for themselves and took on odd jobs, caretaker posts and the like. I knew one who had opened a marina, another who ran a hospice for drug addicts and alcoholics.

I had seen and heard nothing of Dankert Muus since he retired almost ten years ago. But he was in the telephone directory, with an address in Fredlundsveien, a reasonably peaceful location, as the ‘fred’ part of its name suggested, beneath the forest on the Mount Løvstakken side. The odd drug addict or drunk might turn up there too, but a deer was far more likely. Dankert Muus was probably still man enough to chase away anything that might stray onto his territory, whether it was on two or four legs.

On the bus up to Søndre Skogvei I had time enough to reflect that if I had an assignment now, the first in a long time, it would be advantageous to be able to drive my own car. If I was dependent on the local bus services I would have a lot of time to kill and I had never been that murderously disposed. But the very thought of meeting a new day without a dram from a bottle of aquavit sent heavy breakers crashing through me, waves from a vast, dark ocean where I had never found peace.

The house where Dankert Muus lived was a large, semi-detached property, half yellow, half green. Muus lived in the yellow part, with an entrance at the side, midway up a staircase. I rang the doorbell and waited.

The woman who opened was around seventy years old, white-haired, surprisingly petite and with a friendly expression on her face. ‘Yes, what is it?’ she said, looking at me expectantly.

‘Fru Muus?’

‘Yes.’

‘My name’s Veum. Varg Veum. It wouldn’t be possible to have a few words with your husband, would it?’

‘I asked you what this was about.’

‘Well, it’s … a cold case. I’m a private investigator.’

‘Aha,’ she said, pursing her lips as though this was not a profession whose existence she would necessarily accept. ‘Well, Dankert’s in the garden. You can walk round…’ She pointed to the corner of the house at the end of the staircase. ‘You’ll find him there.’

I followed her instructions, completed the ascent of the stairs and rounded the corner of the house. I was confronted with a marvellous garden, impressive to behold even in March, not least for an amateur. I counted two apple trees, various soft-fruit bushes, a dominant rhododendron in the background, several beds of sprouting crocuses, snowdrops and some small, yellow flowers whose name I didn’t know, as well as a freshly laid plot where the season hadn’t quite got going yet. In the midst of this stood the biggest perennial I had ever seen, a Dankertus Muusius, with a much-used spade in his hand, staring at me as if I were a murderous Spanish slug that had strayed into Paradise without a visa from El Supremísimo.

‘So this is where you bury your bodies, Muus.’

He stared at me in disbelief. ‘Veum! What the hell are you doing here?’

‘Inspecting the cemetery.’

‘I really thought I’d seen the last of you.’

‘So you haven’t missed me?’

‘Not for a second, Veum. Not one single second.’

I approached warily, keeping an eye on the spade in case he should strike.

He had aged in these ten years as well. His body didn’t have the same brutal mass I remembered from when he was an inspector at Bergen Police Station, and, even though I had succeeded in inflaming his temper once again, he didn’t have the same fire as before. His hair had gone white, his skin was grey and he hadn’t quite dealt with all the stubble when he had shaved that morning. His gaze was as dismissive as always and he caught me by surprise when he thrust out a huge paw to shake hands and said: ‘I was sad to hear about your partner, Veum.’

I swallowed. ‘So you heard about it then?’

‘I still talk to some of the folk at the station. Jakob pops by once a month.’

‘Hamre?’

He nodded. ‘He’s getting close to retirement as well now.’ Then he added, not without a hopeful glint in his eye: ‘But you must be too, aren’t you?’

‘No, no. People like me haven’t got such an early retirement age as you, you know. And I have nothing to fall back on, yet. Less than nothing, actually.’

‘Well…’ He looked around. ‘I love doing this. Gardening. I don’t suppose you’d have believed that, would you?’

‘No, you’re right there. I’ve never seen you as the crocus type.’

‘But in fact I have been for many years.’

‘You can see how well we knew each other.’

‘Yes.’ He looked at me gravely. ‘So what brings you here after all these years?’

‘A case you worked on during your spell at the station.’

‘Thought so.’

‘I believe it was known as “The Mette Case”.’

A shadow flitted across his face and his eyes darkened even further. ‘I see.’

‘You remember it, of course.’

He nodded. ‘Yes indeed. But not in detail, it’s so long ago. Has someone contacted you about it?’

‘The mother.’

‘Right.’ He waved his hand in the air, struggling to find her name.

‘Maja Misvær.’

‘Yes, that’s it. I remember her. She was absolutely hysterical, of course. Couldn’t understand how we could draw a blank.’

‘Not hard to see why.’

‘No-oo.’ He hesitated, even after so many years. ‘But … you never forget cases like these, Veum. A small child and an unsolved crime. Sometimes I still wake up in the middle of the night and lie there thinking about precisely this case. And a couple of others. Not so strange, perhaps. The unsolved cases are always on your mind.’

‘Could you give me the gist of the investigation? Even if you can’t remember the details.’

He grimaced. ‘I fail to see what a hobby-detective like you can do, and after so many years. But … better to leave no stone unturned.’ He nodded towards the house. ‘It’s too cold to stand out here. Let’s go in for a cup of coffee.’

Muus kicked the soil off his heavy boots and rammed the spade into the bed as a reminder that the day’s work was not yet done. He removed his sturdy gardening gloves and stuffed them in the grey-brown parka he obviously wore outdoors over dark-blue waterproof trousers so that he could kneel down without getting soaked to the skin. Then he led the way to the house and a veranda door at the back.

We went on to the veranda, he pulled off his boots, motioned for me to do the same with my shoes, and then we padded into the kitchen in stockinged feet, where Fru Muus had telepathically already put on the coffee machine. Neither of them said a word to the other, but Muus articulated a few growls, which I interpreted as good-natured, and she nodded and smiled back. For a second or two I felt like an intruder in the Deaf and Dumb Association, but then Muus recovered his powers of speech and grunted: ‘Take a seat, Veum, and I’ll find us some cups.’

He fetched two large white mugs from a cupboard and put them on the table by the window. The kitchen was kitted out in standard Norwegian fashion. On a wall hung this year’s Bergen calendar, with a picture of sunshine, as usual; to the right of the door leading into the apartment a bell rope with a flower pattern, probably embroidered by Fru Muus in her leisure hours while her husband worked overtime serving the general public. Through the half-open door I glimpsed the sitting room with its well-used beige, moss-green and red-speckled furniture: an armchair, half of a sofa and one end of a well-polished coffee table. I saw an oil painting on the wall opposite: a nature motif from a fjord landscape of the kind you found in most Norwegian homes with ageing occupants.

Muus poured coffee straight from the jug into the two mugs, pushed one over to my end of the table and then plumped down on the other chair. His wife withdrew discreetly into the inner rooms with no more than a faint chafing sound, like a distant cricket.

‘Thank you very much,’ I said, lifting the mug to my mouth and tentatively sipping the hot drink.

‘So … what are you after, Veum?’

‘You remember the case, I gather. You said you still wake up in the night thinking about it. Is there anything in particular that bothers you about it?’

His lips curled. ‘No one likes an unsolved case. And this one was especially difficult. In reality there was nothing to find out. She just vanished.’ He snapped his fingers. ‘Just like that. Like a magic trick.’

‘But naturally you initiated a full investigation?’

Muus rolled his eyes at being asked such a stupid question. ‘What do you think? Of course we did. Shall I list the steps we took?’

‘That would be good.’

‘We checked the relationship between husband and wife, to see if there had been any disagreements. Nothing. The father’s alibi was watertight – he was at football training with his son, the poor girl’s brother.’

‘They got divorced some years later.’

‘Yes, we took note of that, but … in fact that’s not so unusual in cases like this. It puts tremendous pressure on the family.’

‘Yes, I know.’

‘We checked him out, both in 1977 and a couple of years later, when we heard about the divorce. The boy stayed with the father when he remarried. That made us reconsider the mother’s role in all of this, but we never got as far as directly suspecting her either.’

‘Maja Misvær being behind the whole stunt?’

‘Yes, but as I said, there were never any grounds for suspicion.’

I took another sip of coffee. ‘And the neighbours?’

‘We checked them out, one by one. Some were away when it happened – it was a weekend. Some were in town. Others were at home, but … What could the motive have been? And where was the girl? We searched every house in the co-op under the pretext that she might have toddled into a storage room, or indeed any room, or that there might have been an accident. That was what we said anyway, although deep down … you never know what lurks behind closed doors. That’s my experience after a long career in the force, Veum.’

‘Yes, mine too, for that matter. The accident theory…’

‘Yes, we checked that out too, of course, properly. It’s quite a way to Lake Nordåsvatnet, but we searched the beach and the water. Nothing. We organised a search party to comb the land around the co-op. There were a lot fewer buildings then than now and enough places for a child to … fall into a pond, get stuck in a bog, slip off a cliff. But all in vain. We didn’t find a trace of her anywhere.’

‘What about a car? A collision? Someone who picked her up and took her?’