7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Varg Veum

- Sprache: Englisch

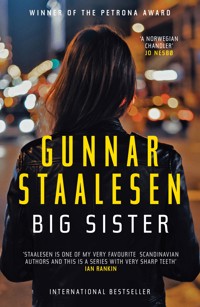

Varg Veum is persuaded to take on the case of a missing teenager, by a half-sister he didn't know he had, in a case that quickly becomes personal … A dark, chilling and startling relevant new instalment in the award-winning Varg Veum series, by one of the fathers of Nordic Noir. ***Shortlisted for the Petrona Award for Best Scandinavian Crime Novel of the Year*** 'Staalesen continually reminds us why he is one of the finest of Nordic novelists' Barry Forshaw, Financial Times 'Chilling and perilous' Sunday Times 'Employs Chandleresque similes with a Nordic Noir twist' Wall Street Journal _________________ Varg Veum receives a surprise visit in his office. A woman introduces herself as his half-sister, and she has a job for him. Her god-daughter, a 19-year-old trainee nurse from Haugesund, moved from her bedsit in Bergen two weeks ago. Since then no one has heard anything from her. She didn't leave an address. She doesn't answer her phone. And the police refuse to take her case seriously. Veum's investigation uncovers a series of carefully covered-up crimes and pent-up hatreds, and the trail leads to a gang of extreme bikers on the hunt for a group of people whose dark deeds are hidden by the anonymity of the Internet. And then things get personal… Chilling, shocking and exceptionally gripping, Big Sister reaffirms Gunnar Staalesen as one of the world's foremost thriller writers. _________________ Praise for Gunnar Staalesen 'Gunnar Staalesen is one of my very favourite Scandinavian authors. Operating out of Bergen in Norway, his private eye, Varg Veum, is a complex but engaging anti-hero. Varg means "wolf " in Norwegian, and this is a series with very sharp teeth' Ian Rankin 'Almost forty years into the Varg Veum odyssey, Staalesen is at the height of his storytelling powers' Crime Fiction Lover 'Staalesen continually reminds us he is one of the finest of Nordic novelists' Financial Times 'Chilling and perilous results — all told in a pleasingly dry style' Sunday Times 'Staalesen does a masterful job of exposing the worst of Norwegian society in this highly disturbing entry' Publishers Weekly 'The Varg Veum series is more concerned with character and motivation than spectacle, and it's in the quieter scenes that the real drama lies' Herald Scotland 'Every inch the equal of his Nordic confreres Henning Mankell and Jo Nesbo' Independent 'Not many books hook you in the first chapter – this one did, and never let go!' Mari Hannah 'With an expositional style that is all but invisible, Staalesen masterfully compels us from the first pages … If you're a fan of Varg Veum, this is not to be missed, and if you're new to the series, this is one of the best ones. You're encouraged to jump right in, even if the Norwegian names can be a bit confusing to follow' Crime Fiction Lover 'With short, smart, darkly punchy chapters Wolves at the Door is a provocative and gripping read' LoveReading 'Haunting, dark and totally noir, a great read' New Books Magazine

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 409

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

Big Sister

GUNNAR STAALESEN

Translated by Don Bartlett

If you look on the map for Buvik, in the county of Ryfylke, you’ll be looking in vain. The place only exists in my imagination, along with all the characters and events in this book. But Bergen, Haugesund and Skudeneshavn do exist, the last time I checked anyway.

—Gunnar Staalesen

CONTENTS

1

I have never believed in ghosts. The mature woman who came to my office on that wan November day was no ghost, either. But what she told me awakened something I had long repressed and opened the door to a darkened attic of family secrets whose existence I had never suspected. From behind my desk I sat staring at her, as I would have done if she really had been just that: a ghost.

2003 had been a volatile year in all ways. I had barely escaped the heavy hand of the law the previous September when the builders started to knock down walls around me. The hotel that had originally occupied the two top floors had now taken over the whole building, and a massive renovation programme was in full swing. With a heavy heart, the hotel director had accepted my old contract with the property owner, which stipulated my right to have an office on the premises for as long as I was running my business. But during the rebuilding phase I had to move out. Until the reopening in May I had worked from a so-called ‘home office’, a corner of my sitting room in Telthussmuget. I had never invited clients home. Most of them I met at various cafés and eateries in town and round about. It had given me an involuntary overview of the quality of coffee served in this region. With a few notable exceptions it was one I could have foregone. I was as black as pitch internally and as nervous as a novice priest at a Black Metal Fest in hell. And, even after several days of twitchy abstinence, this nervousness wasn’t relinquishing its hold.

When I got my office back in May it was still in the same place, four flights of stairs up from the street, but I had lost my waiting room. It had become a hotel bedroom, and my office was now in a corridor in which you had to strain your eyes to find the door that led, if you came on the right day, to where I resided. The waiting room wasn’t a serious loss. As the years had passed it had been of less and less use. I had never walked past without a quick look at the sofa, though, to check if there was another corpse lying there. For those wishing to see me now there were some sofas in the hotel foyer, where the changing pool of desk staff now had the additional dubious role as my receptionists.

They hadn’t done anything to my office. But it still took me a week to tidy up, during which time I took the opportunity to dispose of old crime cases and sort out my filing cabinet. When I had finished this I celebrated by purchasing another bottle of Taffel aquavit, which I carefully placed in the bottom left-hand desk drawer, where the Simers family had traditionally held sway for as long as I’d had the legal right to this office.

In many ways I was content with the result. I had the same office; it was only its environment that had changed. The address was still Strandkai 2, third floor.

Everyone was welcome to bring whatever they had on their minds. It took a lot to surprise me. Unless they came from Haugesund and said they were my sister.

2

She met my gaze. ‘Has this come as a surprise to you?’

‘Not entirely.’

‘Mum told you about me?’

‘No. But after she died I found a copy of your birth certificate and adoption papers.’

She sent me a searching look. ‘And it never occurred to you to make contact?’

‘No, I’m afraid not. I was in the middle of a divorce at the time, and besides … I suppose I thought that if she’d kept it a secret all her life I was showing her a kind of respect by letting bygones be bygones.’

Her eyes held mine. She had introduced herself as Norma Johanne Bakkevik. Born in 1927. Her eyes were clear, a cornflower blue, her hair was silver and, despite her age, it was easy to see she had been a beautiful woman when she was young. But she didn’t remind me of my mother. Her sartorial elegance was a little passé – a dark-blue cape over a red-and-black spotted dress. She was fairly light on her feet for a woman of seventy-six, and there was something determined and focused about her that I couldn’t associate with my mother either, not the way I remembered her.

‘I can understand that. It was only when my adopted parents died and I went through their papers that I discovered the name of the woman who was my mother. When I reached the age of majority they told me I’d been adopted, but I was given to them when I was only a few days old and I’d grown up with them, so for me it wasn’t that important then. They were my parents, and still are, in my head. Your … our … She became a stranger for ever.’

‘Mm.’

‘When I visited her in February 1975 she was surprisingly open, though, once she’d got over the shock.’ She smiled wryly. ‘She had the same expression as you about a quarter of an hour ago.’

‘Right. Did she tell you who your father was?’

‘Do you know?’

‘No.’

‘Yes, in fact she did. A peripatetic preacher who regularly came to Hjelmeland, Ryfylke, where she grew up. I’ve tried to find out about him as well, but it hasn’t been easy. He’s hidden his traces well, if I can put it like that. Peter Paul Haga.’

This went through me like an electric shock. ‘Was that really his name – Peter Paul Haga?’

‘Yes. Does it mean anything to you?’

‘It cropped up in a case I took on several years ago.’

‘Does that case have any relevance?’

‘No. It might sound a bit odd, but it was, in fact, a hundred years old. And Peter Paul Haga played a minor role. As a murder victim actually.’

‘A murder victim!’

‘Yes.’ I gave her a brief rundown of the very special crime case that had come my way right at the end of 1999. She followed attentively but after I had finished she stared into the distance, beyond the office, far back in time.

When she finally returned, she said: ‘Did our mother know about this?’

‘Doubt it. She’d been dead for many years when I got the case, and I didn’t find anything at all about Peter Paul Haga in the papers she left.’

‘What did you find?’

‘Not a great deal. Your birth certificate and the adoption papers, as I mentioned. And some newspaper cuttings about a jazz band calling itself the Hurrycanes.’

‘Really? Was she interested in jazz?’

‘Not as far as I know. I remember her as a quiet soul who used to go to church on Sundays. Without my dad though. He sat at home reading about Norse mythology. I preferred to go walking in the mountains.’

‘Sounds like a strange family.’

‘Yes, I suppose we were.’ Now it was my turn to fall into a reverie.

She broke the silence. ‘Can you remember if she was ever in Haugesund?’

‘Only travelling through. We often used to visit my mother’s parents in Ryfylke in the summer and would take the night boat down to Stavanger. But a couple of times we went through Haugesund because she wanted to call in on a cousin and an old aunt there.’

‘Yes, I asked her the same question when I visited her. All she told me was that she’d been to a cousin’s wedding there in January 1942. By the way … I think she said the bridegroom came from Bergen and played in a band here.’

‘Maybe the Hurrycanes. I suppose that’s why the newspaper cuttings were among her papers.’

‘Yes, maybe.’

‘Have a look at this.’ I opened a desk drawer and rummaged around until I found a yellowing envelope. I took it out, opened it and held up one of the old cuttings I still had. It was from a local paper, Bergens Tidende by the look of it, some time in the 1950s: a jazz quintet from the interwar years known as the Hurrycanes was going to perform at somewhere called The Golden Club. Underneath the picture were all five names of the musicians. The only one I had taken any note of was the saxophonist, Leif Pedersen, because a childhood pal of mine had mentioned him in connection with a house I had searched. In fact I had visited this house as a child with my mother – it belonged to a friend of hers who was related to this self-same Pedersen. I remembered thinking this was perhaps why she had cut this article from the newspaper, not that I had given it any further thought. But now Norma had come up with another plausible explanation.

Out of habit I scribbled down The Hurrycanes? in my notepad. If I had a quiet day, and experience told me there would be quite a few of them, I could always delve deeper, for no other purpose than entertainment.

‘Have you got any children, Varg?’

‘A son, Thomas, who lives in Oslo, and a little grandson, Jakob, who’s two years old. And you?’

At once her face was sad. ‘I had two. Petter and Ellen. But Petter died in 1980. He was on the Alexander Kielland oil platform that capsized. But he also left one child. Karen, who is twenty-four now. Ellen hasn’t had any children.’

‘So Mum has some descendants she never met.’

‘Yes, she has. I met her only once. On the 5th of February 1975. That was when she told me about you, and since then I’ve followed your movements, at lengthy intervals, and always from a distance. But I’ve seen your name in the news sometimes, especially now that we can search online.’

‘You’re online?’

‘Yes, of course. Does that surprise you? I may be well over seventy, but I’m not decrepit quite yet.’

‘Of course not. I’ve never been the quickest at these things myself, so…’ I gestured apologetically.

She smiled condescendingly. ‘But … you might be wondering why I’m visiting you today of all days?’

‘Yes, now you mention it, I…’

Her shoulders seemed to slump, she was like an old doll casually tossed aside by a child suddenly too old to play with such things. ‘In fact I’ve got a commission for you.’

‘A commission?’

‘Yes, a case, or whatever you call them.’

‘Both are an integral part of my vocabulary.’

Again she was lost in thought. Then she visibly pulled herself together. ‘This is about my god-daughter. She’s gone missing.’ I just looked at her, waiting for more, and she added: ‘From here. From Bergen.’

3

What she told me was not so different from what I had heard many times before, but the fact that the person who was telling me was my own half-sister gave it an extra edge. I listened attentively and made some notes as and where necessary.

Emma Hagland was nineteen years old, born and raised in Karmøy, Rogaland. She had taken her final exams at Haugaland School in June and moved to Bergen in the course of the summer to start her nursing course at the university here. After some to-ing and fro-ing she had moved into a kind of collective with two other girls. They shared a flat in a block in Møhlenpris, in Konsul Børs gate.

‘The problem was,’ she said, ‘that it was next to impossible to get in touch with her. If we rang her she never picked up. However, she did reply to texts, now and then at any rate.’

‘I suppose she was busy, wasn’t she? At the beginning of an academic year there’s bound to be a lot to take on board.’

‘Of course, but we wanted to know how she was! How she was getting on. After a while we began to get quite desperate.’

‘Yes, I can imagine.’

‘But then, a few weeks ago, it got even worse. We kept ringing. No answer. I sent off one text after another. No answer to them, either. We called her best friend from school, Åsa. But she’s studying in Berlin and had only spoken to her on the phone in recent months. She knew nothing. We were at our wits’ end.’

‘But you had her address, didn’t you?’

‘Yes, we did,’ she nodded. ‘We rang her landlord, but he just said he didn’t know what the problem was. People came and went. It was like that all the time, he said.’

‘What did he mean by that? That she’d moved out?’

‘Yes, it transpired that was what had happened. After some discussion with the landlord we got the names of the girls she shared the flat with. We managed to contact one of them on her mobile. Not that it helped much. Emma had just moved out, she said, at the end of October. She had paid her share for the month and, from what this girl had gathered, Emma had received a better offer somewhere else.’

‘I see. But then…’

‘Still no answer from her phone!’

‘Have you got the names of these people? The landlord and Emma’s room-mates?’

‘Yes.’ She gave them to me and I noted them down in my notepad: Knut Moberg. Kari Sandbakken. Helga Fjørtoft. ‘The girl we spoke to was Helga.’

‘Just explain to me … You talk about “we”, but my understanding was you’re only her godmother. She has a family, I take it?’

Her face clouded over. ‘Yes, she has, but … it’s a bit complicated. I’m in contact with her mother. She lives in Haugesund.’ She appeared to hesitate before continuing. ‘The father left them when Emma was two.’ Another short pause, then she finished what she had to say: ‘He lives in Bergen.’

‘Right! So you’ve been in contact with him?’

‘Yes, we have, but he says he had no idea she was in town. He … They’ve never communicated.’

‘Never? Not since she was two?’

‘No. As I said, it’s a bit complicated.’

‘Norma, I used to work in child welfare and in all the years I’ve run this business…’ I made a sweeping gesture with both arms, as though I were showing her around the royal palace, ‘…I’ve seen and heard all manner of things. It’ll take a lot to shock me.’

She nodded. ‘I understand. But this is still difficult to talk about.’

‘There are many reasons why people split up. The burden on young parents can simply be too much, with disturbed nights and difficult days, that kind of thing. Then, of course, the romance has gone and one of them meets someone else. And there can be other reasons. But since we’re talking about a father who’s had no contact at all with his daughter for seventeen years, from what you’ve told me, the most likely assumption is that this is linked with sexual abuse.’ As she didn’t answer at once, I added: ‘Or substance abuse, of course. Alcohol or some other stimulant.’

She nodded thoughtfully, as though she were reflecting on what I’d said and weighing up the likelihood of what might have been the cause.

‘Do you know the family well?’

‘Her grandmother was a good friend of mine. I’ve known her mother ever since she was a little girl. That was why I was asked to carry her at the christening in May 1984, of course. In Avaldsnes Church.’

‘So I assume you know why the father left them?’

Her eyes roamed around, as if to see what I had on the walls, but found nothing to detain them and came back to me. ‘She’s not in a very good place, Ingeborg isn’t.’

‘Ingeborg. That’s…?’

‘Emma’s mother. I do what I can to support her.’

‘Has she any other children?’

‘No, only Emma. That’s what makes her so desperate not … to lose her.’

‘Let’s not cross that bridge until we come to it. I’m sure there’s a natural explanation for everything. Have you contacted the police?’

She gave a slanted smile, infused with cynicism. ‘They said more or less the same. There was sure to be a natural explanation.’

‘The police here in town?’

She nodded.

‘Do you remember who you spoke to?’

‘It was a woman. Bergesen, I think she was called.’

‘Annemette. I can have a word with her.’

‘I don’t know if that’ll help. They haven’t done a thing. She suggested that Emma’s phone might’ve been stolen. That goes on all the time, she said.’

‘But she would’ve rung her mother from a new one, wouldn’t she?’

‘Yes … probably.’

‘Well, I’ll see what I can dig up.’

‘Of course you’ll be paid. I haven’t come here to exploit you. Because we’re family, I mean.’

‘That would be a first,’ I said. In one of my desk drawers I found my list of fees and passed her a copy across the table. ‘Here you can see what you have to agree to anyway.’

As she read, her face became tauter than a temperance preacher’s as he studied the wine list in a gourmet restaurant. I hastened to add: ‘But I give a discount to close family. That goes without saying.’

She nodded and smiled, and when she looked at me again her mask slipped, as though she was about to shed a tear. ‘Thanks, Varg,’ she said with a tiny pause before my name.

‘I still haven’t had an answer to my question. What was the reason the father left them?’

‘It was something … sexual. Not with Emma, though.’

‘OK. So?’

‘It was an old business. When he was a young boy. And then it reared its ugly head again.’

‘In what way?’

‘I’m not quite sure, but … it was something he’d done when he was very young, and Ingeborg got to hear about it … She kicked him out.’

‘I see. But he lives in Bergen, you say. Have you got his name and address by any chance?’

‘I’ve definitely got his phone number. And his name, of course. Robert.’

‘Robert Hagland?’

‘No, Ingeborg reverted to her maiden name after the divorce, and Emma took it, too. Robert’s surname was Høie, but he added another when he moved. Now he calls himself Robert Høie Hansen. In fact, his father’s name was Hans.’

‘I’ll find him then.’

Her brow furrowed. ‘But don’t tell him it was me who sent you.’

‘No, no. Discretion’s my middle name. That ought to be on my business card. Varg D. Veum. One more thing, though. I hope you have a photo of Emma.’

‘Yes, of course I do. How could I forget?’

She opened the robust handbag she had with her, stuck a hand inside and took out an envelope. She handed it to me and I opened it. There was a sheet of photos inside, the kind you get from a machine. One of them had been cut out. The others were almost identical. Emma Hagland stared at me with a serious expression, smooth blonde hair, thin lips and an indefinable melancholy in her eyes, like a newly fledged confirmand being confronted for the first time with the realities of life.

‘Are they any good?’ Norma asked.

‘If that’s how she looks now, yes.’

‘They were taken in July, when she came to study here.’

‘Well, I’ll see what I can find out. But I need her phone number.’

She gave it to me. ‘And here … I’ve got her bank card number, if you have the opportunity to check on it.’

‘I’m afraid only the police can do that, but I’ll see what I can do. This is my business after all.’ I smiled at her encouragingly. ‘It’ll be fine, you’ll see…’

She smiled back, if not with quite the same conviction. ‘Anyway, it was nice to meet you finally.’

‘It would’ve been even nicer if this hadn’t been the reason. But we’ll have to talk family next time. What are you going to do now? Go back home?’

‘Yes, I came on the coastal bus this morning and I’ll be going back as soon as we’ve finished.’

‘I might have to take a trip down there in a while. If needs must, I mean.’

‘In which case, you’ll be more than welcome!’

I thanked her and accompanied her to the door. Before we parted she leaned forwards quickly and gave me a hug.

After she had gone I stood staring at the closed door as though she might reappear at any moment with a couple more surprises up her sleeve. My astonishment was still deep within me and it was going to take a few days before I would be able to get over it. Good job I had something to do. Just get on with it, I told myself.

But still I wasn’t quite ready. Looking out of the window, I felt as if I was being dazzled, not by the sun but by the light from a past I never wanted to relinquish, a childhood which in some way had made me and my half-sister the people we had become. The stamp your parents imprint on your brow is there for ever, visible or not. You rarely get to know the secrets they take with them to the grave.

4

How many secrets can a person have? Why had I not heard about my half-sister before? Might my father not even have known? Was there anything else they had kept secret and I would never find out?

In my mind I returned to my childhood home on the Nordnes peninsula of Bergen. The street was Fritznersmuget, right on the very edge of the cluster of timber houses between Nordnesgaten and Nordnesveien that had survived the bombing in June 1940 and the huge harbour explosion in April 1944. When I was growing up there we were surrounded on all sides by houses. In the last year of my mother’s life everything around us was demolished. Our house stood there like a last redoubt on the battlefield of what once had been a neighbourhood of small dwellings, but which in the years to follow were replaced by four- and five-storey blocks in the style the town planners of the 1940s had determined the whole of Nordnes was to adopt: from a timber-house village to a concrete townscape. Fortunately, they couldn’t afford to implement everything at once. By the time they had reached Nykirkeallmenningen in 1960 they had changed their minds and the timber constructions along Lille and Ytre Markevei were spared, despite being on the original list for demolition.

From as far back as I could remember, I always had an image of my father, tram conductor Anders Veum, with his nose in a book about Norse mythology, the subject that fascinated him most, for some reason. He died in 1956, when I was fourteen, and it still hurt that I never really got to know him. For that matter, I didn’t get to know my mother, either. They were both closed, private individuals who kept their secrets to themselves. One of these – perhaps the biggest – had just walked out of my office and left me wistful and melancholic, lost in memories of a time that would never return, memories that would inevitably be erased one day when we, still cherishing them, were also gone.

The little I knew about my parents’ past I had from my mother’s cousin, Svend Atle Moland, whom I had met on a few occasions. Best of all I remembered the journey to Hjelmeland, to my maternal grandfather’s funeral in 1960. Svend Atle, my mother and I went there from Bergen. At that time Svend Atle had recently retired from the police. On the return journey by boat from Stavanger he and I stayed up in the saloon after my mother had gone to sleep in the cabin she shared with another woman. Svend Atle had treated me to a bottle of beer and as the occasion was already intimate he had begun to tell me about the time he met my mother and father, long before the war broke out.

‘Ingrid came to Bergen on the Haugesund boat in 1928 and I’d been sent to the quay to welcome her. By chance we met Anders on the way up to Blekeveien, where my parents would give her lodging, and as it was the year the Great Exhibition was in town, we invited Ingrid to a beer at the exhibition pavilions that evening. And, as they say in the papers, the rest is history. They became a couple.’

‘Was my father already working on the trams then?’

‘Yes, he was. He came to Bergen in 1926, during the great tram strike, and committed the cardinal folly of accepting employment on the trams, unaware that it was as a strike-breaker. It took him years to shake off the taint. And I can clearly remember … there was always a kind of sadness about Anders, as though he were grieving over something he never revealed to us. He didn’t smile much, your father. Ingrid is by nature much more light-hearted, but even she has moments of being pensive and distant.’

‘And she worked at the United Sardine Factory in the dockyard, she said.’

‘Yes, she must’ve been there until she had you, during the war. For the first few years she was in service, but after she and Anders got married and no children were immediately forthcoming, she was employed at USF. Canning sardines for king and country.’

He didn’t have much more than that to tell me. Slowly he moved on to talk about the years when he had been in the police and some of the cases he had worked on as a detective. Later it struck me several times that it might have been in the course of this conversation that I initially got the idea of starting up in the profession myself, although my childhood friend Pelle and I had already opened our very first detective agency in the early 1950s, in one of the blocks that was being constructed in Nordnesveien. Our only big case was tailing a girl from Nordnes to Minde; she had recently moved into our street and her name was Sylvelin. All we received for our pains were the first grazes to our hearts, both of us.

Later I only met Svend Atle Moland on rare family occasions, most of them funerals. After he died himself during a walk on Mount Gulfjell in 1978 I went to his funeral in Møllendal Chapel without ever having told him that I had actually opened my own private detective agency three years before. However, he may have heard from other quarters because it wasn’t exactly a secret.

My mother had died three years earlier, and now here I was, almost thirty years later, wondering if there was even more she hadn’t told me, apart from the fact that I had a half-sister in Haugesund I had never met.

I was unlikely ever to find the answer. With renewed determination I shook off these gloomy thoughts, pushed the chair back from my desk, went to the clothes stand and put on the coat that hung there. Then I walked across Nygårdshøyden to start work on the job I had been given by Norma Johanne Bakkevik, which was the name on the business card she had left with me before taking her leave.

In November night falls quickly and the street lamps were lit long before I had arrived at the address in Konsul Børs gate. The front door was locked – hardly surprising in this part of town. I leaned forwards to study the names on the list beside the loudspeaker. There seemed to be a motley collection of tenants: some foreign names, some Norwegian ones. I found both Fjørtoft and Sandbakken beside one of the bells. On the same strip a third surname had been crossed out, although I was still able to read Hagland underneath. At the top of the list was Moberg, the surname of the landlord Norma had mentioned. So why not? I pressed the bell and waited for a response.

5

A woman’s voice answered. ‘Hello?’

‘Hello. My name’s Veum. Can I talk to Knut Moberg?’

A slight pause. ‘I’m afraid not. He’s not at home. What’s it about?’

‘I have a few questions regarding one of your tenants.’

‘I see.’

‘Emma Hagland.’

Another slight pause. ‘She doesn’t live here any longer.’

‘No, precisely. She’s gone missing.’

‘Oh. Well … What did you say your name was?’

‘Veum. Varg Veum.’

‘You’d better come in. I’m on the third floor.’

The lock buzzed and I pushed the door open.

‘Thank you,’ I said, but she had already gone.

It was a classic ‘chimney’ house from the 1890s, properly renovated and fireproofed since then, I hoped. At any rate it seemed to be in fairly good condition. On the left, two lines of post boxes hung from the wall. On the right there was a poster with what turned out to be the house rules. Next to it hung a fire extinguisher. The house smelt fresh and clean, and the neon tubes on the ceiling emitted clear white light above me as I went towards the staircase and headed upwards. Even though I had passed sixty a year ago I was still more than fit enough to manage three flights of stairs in Møhlenpris without having to stop on every landing for breath.

On the second floor I noticed a door with a trim sign stuck to the door with no visible sign of an adhesive. My PI brain assumed the solution was double-sided tape. A white piece of cardboard had been cut into an elegant oval shape and inscribed with a felt pen. The two names on it were formed in such beautiful handwriting it bordered on calligraphy: Helga Fjørtoft & Kari Sandbakken.

I climbed the last flight of stairs and was met in the doorway by a woman in her early forties. ‘We haven’t got a lift,’ she said with a little smile.

‘I noticed,’ I smiled back.

‘Exercise is healthy, they say.’

‘That’s what my GP said last time I was there. Ten years ago.’

She arched her brows. ‘Fit as a flea then?’

‘Fitter. I’m very fussy about my hosts.’ I proffered my hand. ‘Veum.’

She shook hands. ‘Ellisiv.’ And she held my hand for longer than normal.

‘Unusual name.’

‘A queen’s name. She was married to Harald Hardråde, if I remember correctly.’

‘So that’s why you’re so elegantly dressed on a Monday?’

‘No, it’s because my husband isn’t at home.’ She uttered a sound that was halfway between a snigger and a hiccup, and at once I thought: she’s not sober. In fact she could barely stand. That was why she was resting her hip against the doorframe in a pose that had initially seemed quite inviting.

Ellisiv Moberg had light streaks in her dark, dishevelled hair. She was pale, with big bags under her eyes, insufficiently camouflaged under the make-up, and her pupils were large and shiny, framed by a mixture of blue and sea-green. Her dress was elegant enough, finishing above her knees, and with big red Chinese dragons on a dark-blue background and a split so high up one side that the Promised Land couldn’t have been far away. ‘May I offer you something?’

‘Well, actually…’

‘A glass of wine?’

‘It was Emma Hagland I…’

‘My husband won’t be coming home today.’

‘No? Where is he, if I might ask?’

‘On the road.’

‘On the road?’

‘Visiting every contact he has from Ålesund to Stavanger.’

‘And by contacts you mean…?’

‘He has an agency.’ She ran the tip of her tongue over her full lips to one corner of her mouth, where it rested like an inquisitive little creature. ‘Wine. I can offer you a superlative Saint-Émilion.’

‘Strictly speaking, I’m a beer and aquavit man.’

‘Who never likes a taste of something different?’

‘Oh, yes. It happens.’ I tried to demonstrate my utmost regret as I added: ‘But right now I’m a little strapped for time, so…’

She sighed loudly and rolled her eyes. Then her gaze hardened. ‘Right! I can take a hint. What are you actually after?’

‘I’m here regarding an Emma Hagland.’

‘Yes, I gathered that. She doesn’t live here any more. I told you.’

‘She didn’t stay for long, I understand.’

She reached out an arm, but stopped mid-movement, as she lost her balance. Annoyed, she said: ‘No. My husband takes care of the tenants. They only come to me if they have complaints.’

‘And what do they complain about?’

She waggled her head. ‘Well, what do they complain about? The water’s not hot enough, the radiators don’t work, the neighbour downstairs plays his music too loud … yada yada yada.’

She turned towards the hall and I saw her arm move to the door to close it. She failed at her first attempt.

‘So why did she move out so quickly? Do you know anything about that?’

She turned her head slowly from side to side. ‘No.’

‘I’d better come back another day. When your husband’s here maybe.’

She appeared to be considering this, then she nodded. ‘Yes, you do that.’ She sent me a last despairing glance before she went behind the door and pushed it until it locked in my face.

I stood there for a moment. Imagining her sinking to the floor on the other side. But that was only in my imagination. In reality she had probably staggered over to the superlative red wine and raised her glass in a sad salute to Émilion and whatever he or she was a saint of. As for me, I went down one storey and rang the bell at Helga & Kari’s.

6

The young woman who had opened the door a fraction peered through the crack, keeping the security chain on as an insurance policy between her and reality. She studied me with a gaze that seemed anxious, almost jumpy. She had short, slightly messy, dark-blonde hair, a face with no make-up and a mouth that shook like a leaf in autumn, just before it falls.

I put on my very friendliest smile, introduced myself slowly and clearly, and told her the reason for my call.

‘Emma? She doesn’t live here any more.’

‘Yes, I know. But her family’s very concerned about her.’

‘Family?’ She shot me a sceptical look.

‘Her mother anyway. I’ve been commissioned to find out what she’s doing.’

‘Commissioned?’

‘I’m a private investigator.’

Her eyes widened and she immediately went to close the door. I discreetly placed my shoe in the gap, hoping she didn’t have too strong an arm. ‘I have to find out what you know. Are you Kari?’

‘No, I’m Helga.’

‘If you don’t want to let me in, we can go and have a cup of coffee somewhere.’

‘No, it’s fine. Let me just…’ She pointed to the security chain; ‘You’ll have to…’ and nodded towards my shoe.

‘Right.’ I withdrew my foot, not entirely sure that was the right decision.

She closed the door completely. Then I heard her unhook the chain, and she opened up again. ‘Come in.’

‘Thank you.’

I followed her into the plain, featureless hallway. She hesitated for a moment then took me through the second door to the right. ‘This is … our common room,’ she said.

It was sparsely furnished as well. In one corner there was a television that must have been ten years old or more. At the opposite end there was the traditional coffee table, sofa and armchair arrangement. The table was scarred with rings left by glasses and bottles and not without a certain coating. I could imagine it had been surrounded by sundry intakes of students. Møhlenpris was the closest neighbour to the university in Bergen and several student collectives were taking over the old flats in the area. The pictures on the wall looked to have survived a couple of generations – 1980s’ pop art, more circles than squares, as if marking the distance from the previous decade when the dream of world revolution had dominated the scene. On the only bookcase I saw the spines of some popular novels in bestseller format and a handful of paperbacks of the kind you have to be very careful not to call women’s books, at least not with women present.

In the middle of the table there was an empty wine bottle with a candle forced into its neck, but the bottle looked quite new and the candle had only burned down a little. As yet there was no pattern of melted wax. I noticed the name on the label: Cheval Blanc Saint-Émilion.

She pointed gauchely to the sofa, as a sign that I could sit there. I followed her suggestion. She sat down on the chair opposite. Her choice of clothes was simple: faded jeans and a plain grey jumper, and on her feet narrow, brown slip-on shoes. After sitting down she tucked her legs underneath her bottom and placed her hands on her knees as if to have full control over all movable parts.

‘I haven’t a clue where she is…’ she announced.

‘No? But she did move out?’

‘Yes.’ She nodded several times as though to make sure I got the point. ‘She took all her things with her, even if that didn’t amount to much. She put everything in one suitcase.’

‘Surely she must’ve said where she was going?’

She chewed her lip and eyed me nervously. ‘No. Should she have done?’

‘Yes. What about her post?’

‘We hardly get any. I don’t know if she’d even registered her move here. It wasn’t that long ago she moved in anyway.’

‘In the summer, I was told.’

‘Yes, I suppose it was. The end of July.’

‘But … she must’ve registered her move officially?’

‘I’m sure she did.’

‘Well, I can check on that. How did you get to know each other?’

‘We put up notices all over the place, at the student centre and the various colleges, saying we had a room free, and she was the first person to contact us. We asked the landlord if that was OK, and he said it was. So she moved in straight afterwards.’

‘She talked to the landlord as well, did she?’

She nodded. ‘Yes, we have to of course. We sign a contract with him.’

‘Knut Moberg?’

‘Yes.’ She sent me an enquiring look. ‘On the third floor.’

‘Yes, I was there, but only his wife was at home.’

She just nodded slowly, without making a comment.

I focused on the empty red-wine bottle with the new candle. ‘Is he a nice landlord?’

Again a hunted look flitted across her face. ‘Yes, I suppose he is. We don’t have anything to do with him.’

‘No?’

‘Not unless something needs doing. We pay the rent online.’

‘Nothing black in other words.’

‘Black?’

‘Yes, you know, under the table.’

Still she appeared not to understand what I was talking about, and I decided not to pursue the matter this time.

‘Why did she move out so quickly?’

She looked down as she shrugged her shoulders. ‘Dunno.’

‘Did you fall out?’

Her eyes shot up. ‘Fall out? No! We were the best friends in the world, Emma and I.’

‘What about Kari and Emma?’

She hesitated. ‘Not such good friends perhaps.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘Well, Kari may be a bit more direct than I am.’

‘Anything particular you have in mind?’

‘No, nothing more than what I said.’

‘The two of them quarrelled?’

‘No, no, they didn’t quarrel. But … I guess they had their own opinions, both of them.’

‘What about?’

‘You’d better ask Kari about that.’

‘OK. Where is Kari?’

‘Now?’

‘Yes.’

‘Out. She didn’t say where she was going.’

‘So you don’t know when she’ll be home?’

‘No idea.’

I sighed. ‘Well … tell me … did you have any impression of Emma in the time she lived here?’

‘Mm, any impression…?’ She looked to the side of me, towards the window, as though the answer lay outside.

‘You must’ve chatted?’

‘Yes, we did.’ Now it was her turn to focus on the wine bottle with the candle. ‘We were together some nights, just her and me, when we were, erm, a little … pixilated.’

‘Oh, yes?’

Now she looked straight at me. ‘We talked about our fathers. How lucky she’d been to get shot of hers early on! Even though she mightn’t have seen it like that. While I could’ve coped very well without mine!’

Two big red flushes spread across her cheeks, but I wasn’t there because of her, so I made no attempt to enquire further. Instead I said: ‘Her father lives in town though, doesn’t he?’

‘Yes, and that was why things became a little intense for a while. Why we began to talk at all.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘She said … She said she wanted to go and see him. She’d found his address and all that. But I said: “Are you sure you want to? You don’t know who he is, why he left you and why he never maintained contact.”’

‘Ah, so you knew that?’

‘She’d already told me: no contact.’ And then came another personal outburst: ‘She has no idea how lucky she was!’

‘What happened then? Did she visit her father?’

She slowly inclined her head. ‘Yes.’

‘And … did you find out how it went?’

She shrugged. ‘No, but she seemed stressed when she returned that evening. When I asked her how it had gone she didn’t want to talk.’

‘And that was when?’

‘In September.’

‘And what happened then? Did she visit her father again?’

‘She never talked about him, but I felt … I don’t know. I think it’d had an effect on her, somehow, whatever happened. At any rate she became even more introverted after that.’

‘And when did she decide to move out?’

‘At the end of October.’

‘Because she’d received a better offer elsewhere?’

‘Where did you get that idea from?’

‘That was what one of you said when Emma’s family phoned from Haugesund.’

‘That must’ve been Kari they spoke to. I haven’t spoken to anyone.’

‘I’d better … I take it you have Kari’s phone number, do you?’

‘Yes.’ She cast around. Then she got up and went towards the door. ‘Just a minute.’

She came back immediately with a phone in her hand. She pressed a few keys and found the correct number. She held out her phone for me, so that I could tap the number into mine. ‘Thank you. I’ll ring her later. And yours?’

She gave me that, too.

‘Could you tell me which day it was that Emma moved out?’

‘Which day?’

‘Yes, or the date.’

‘It was a Wednesday.’ She looked at her phone and opened the calendar. ‘It must’ve been the 29th of October.’

‘Sure?’

‘Yes, because two days later she had to be out. Change of month and another month’s rent to pay.’

I noted the date. Then I nodded towards the wine bottle on the table between us. ‘Isn’t that pretty expensive wine?’

Once again she shrugged. ‘Kari got it earlier this autumn. It wasn’t the kind of wine Emma and I drank … on the evenings I mentioned. Ours was a bag-in-a-box, so to speak.’

‘Well,’ I started, taking out my business card. ‘Here you are. You’ve got my number, address and everything you need if you remember any more. And I’ll be back later. I have to have a chat with Kari, I think.’

She nodded in acknowledgement.

‘Thank you for everything you’ve told me.’

She accompanied me to the door and closed it firmly behind me as soon as I was outside.

When I was back on the street I dialled Kari Sandbakken’s number, but all I got was a prerecorded answer: Hi, this is Kari. I can’t take your call right now, but if you leave a message, I’ll call you back. Bye.

‘Hi,’ I said, feeling as stupid as I always did when I was talking to a machine. ‘This is Veum. I need to ask you some questions regarding Emma Hagland. Could you call me? Thank you.’

But the thanks didn’t help. She didn’t call back, not that night, nor later.

7

I had no problem finding Robert Høie Hansen in the telephone directory. The address gave me some bad vibes though. Sudmanns vei was where Beate moved when she left me for Lasse Wiik thirty years before, never to return. I had never got any further than the front door of the house they shared, when I was picking up or handing over Thomas before or after his weekend visit. As soon as he was big enough he came to me under his own steam. But now Lasse Wiik was dead, Beate lived in Stavanger, and I had no idea who had bought their house. I glanced up at it as I passed, but I didn’t notice any great changes since the 1980s when I had last been there.

From Sudmanns vei you have Mount Sandviksfjell towering up behind you, with the steep, paved Stoltzekleiven trail like a kind of zip in the middle, and the view of Byfjord and its surrounding splendours: the islets of Svineryggen, Måseskjæret and Kristiansholm, which are all now landfast. In days gone by they used to hang thieves on Kristiansholm. Later the town had a seaplane harbour and still now the occasional seaplane takes off or lands there. Over the last decade the other two islets had acquired modern high-rise buildings.

Robert Høie Hansen lived on the slope at the lower end of the road, behind a panel fence stained the same colour as the house, which was older than the one where Beate had lived, probably built during the interwar years. In a little carport to the right of the garden gate was what looked like a sizeable motorbike, covered in a grey, tailor-made tarpaulin and secured with a chain and a padlock to a post. The garden was reasonably well kept with no eye-catching features that would stop you in your tracks.

I unlocked the garden gate and stepped inside. When I was halfway to the front door, it opened. A small, lean woman, dressed in a red-and-black tracksuit with silver reflective stripes down the arms and legs, rushed out on slim running shoes and had already closed the door before she caught sight of me and paused.

‘Yes?’ she said. ‘Anything I can help you with?’

‘Robert Høie Hansen. Does he live here?’

‘Yes, that’s my husband. What do you want with him?’

She was wearing a white hat pulled down well over her hair, which prevented me from seeing more than a few dark-red strands sticking out at the back. Her face was slender and dotted with pale freckles, and it looked as if she had left her eyebrows indoors. Her eyes were narrow and bluish-green and she had a slight tendency to squint. She jogged impatiently on the gravel and cast a longing glance at the mountainside behind me.

‘It’s a family matter.’

She eyed me sceptically. ‘Oh, yes? Not that hysterical daughter of his again, I hope.’

‘Are you referring to Emma?’

She rolled her eyes. ‘So it is … again!’ She half turned to the door. ‘Well, he’s at home. You just have to ring the bell. He’ll explode with delight. As for me, I’m off up there.’ She pointed to Stoltzekleiven and the weather vane on the mast at the top, an arrow, hard to see at this time of the day.