7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Varg Veum

- Sprache: Englisch

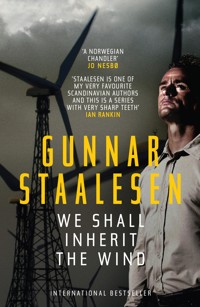

Varg Veum takes on the perplexing case of a missing wind-farm inspector and gets more than he bargained for, as religious zealots, environmental terrorism and then murder take centre stage … The gripping next instalment in the award-winning Varg Veum series, by one of the fathers of Nordic Noir. 'Not many books hook you in the first chapter – this one did, and never let go!' Mari Hannah 'Mature and captivating' Rosemary Goring, Herald Scotland 'Moving, uncompromising' Publishers Weekly _________________ 1998. Varg Veum sits by the hospital bedside of his long-term girlfriend Karin, whose life-threatening injuries provide a deeply painful reminder of the mistakes he's made. Investigating the seemingly innocent disappearance of a wind-farm inspector, Varg Veum is thrust into one of the most challenging cases of his career, riddled with conflicts, environmental terrorism, religious fanaticism, unsolved mysteries and dubious business ethics. Then, in one of the most heart-stopping scenes in crime fiction, the first body appears… A chilling, timeless story of love, revenge and desire, We Shall Inherit the Wind deftly weaves contemporary issues with a stunning plot that will leave you gripped to the final page. This is Staalesen at his most thrilling, thought-provoking best. _________________ Praise for Gunnar Staalesen 'There is a world-weary existential sadness that hangs over his central detective. The prose is stripped back and simple … deep emotion bubbling under the surface – the real turmoil of the characters' lives just under the surface for the reader to intuit, rather than have it spelled out for them' Doug Johnstone, The Big Issue 'Gunnar Staalesen is one of my very favourite Scandinavian authors. Operating out of Bergen in Norway, his private eye, Varg Veum, is a complex but engaging anti-hero. Varg means "wolf " in Norwegian, and this is a series with very sharp teeth' Ian Rankin 'Staalesen continually reminds us he is one of the finest of Nordic novelists' Financial Times 'Chilling and perilous results — all told in a pleasingly dry style' Sunday Times 'Staalesen does a masterful job of exposing the worst of Norwegian society in this highly disturbing entry' Publishers Weekly 'The Varg Veum series is more concerned with character and motivation than spectacle, and it's in the quieter scenes that the real drama lies' Herald Scotland 'Every inch the equal of his Nordic confreres Henning Mankell and Jo Nesbo' Independent'With an expositional style that is all but invisible, Staalesen masterfully compels us from the first pages … If you're a fan of Varg Veum, this is not to be missed, and if you're new to the series, this is one of the best ones. You're encouraged to jump right in, even if the Norwegian names can be a bit confusing to follow' Crime Fiction Lover 'With short, smart, darkly punchy chapters Wolves at the Door is a provocative and gripping read' LoveReading 'Haunting, dark and totally noir, a great read' New Books Magazine 'An upmarket Philip Marlowe' Maxim Jakubowski, The Bookseller 'Razor-edged Scandinavian crime fiction at its finest' Quentin Bates

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 402

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

PRAISE FOR GUNNAR STAALESEN

‘Gunnar Staalesen is one of my very favourite Scandinavian authors. Operating out of Bergen in Norway, his private eye, Varg Veum, is a complex but engaging anti-hero. Varg means “wolf” in Norwegian, and this is a series with very sharp teeth’ Ian Rankin

‘The Norwegian Chandler’ Jo Nesbø

‘One of the finest Nordic novelists in the tradition of Henning Mankell’ Barry Forshaw, Independent

‘Staalesen’s mastery of pacing enables him to develop his characters in a leisurely way without sacrificing tension and suspense’ Publishers Weekly

‘Gunnar Staalesen was writing suspenseful and socially conscious Nordic Noir long before any of today’s Swedish crime writers had managed to put together a single book page … one of Norway’s most skillful storytellers’ Johan Theorin

‘The Varg Veum series stands alongside Connelly, Camilleri and others, who are among the very best modern exponents of the poetic yet tough detective story with strong, classic plots; a social conscience; and perfect pitch in terms of a sense of place’ EuroCrime

‘Norway’s bestselling crime writer’ Guardian

‘An upmarket Philip Marlowe’ Maxim Jakubowski, The Bookseller

‘In the best tradition of sleuthery’ The Times

‘Hugely popular’ Irish Independent

‘Among the most popular Norwegian crime writers’ Observer

We Shall Inherit the Wind

GUNNAR STAALESEN

Translated from the Norwegian by Don Bartlett

Contents

WE SHALL INHERIT THE WIND

If you go in search of Brennøy, in Gulen, on the map, I’m afraid you will be disappointed. This place and all the characters in the book are products of the author’s imagination and do not exist in reality. But you won’t need to look far for plans for wind turbines, not in Gulen or anywhere else …

1

They say a dying man sees life passing before his eyes. I don’t know. I haven’t died that many times yet. But I do know it happens if you have the misfortune to sit beside someone on their death bed.

I sat at her side in Haukeland Hospital, looking at her battered face, the needles in her arm, the probe in her nose, the tube in her mouth and the oscillating lines on the screen above her bed, which showed her heart function, blood pressure and the oxygen content of her veins, and I felt as if I were watching a stuttering amateur film of the years we had known each other, played on a somewhat antiquated projector I had never quite been able to focus. But then I was no technical whiz. I never had been.

I met Karin Bjørge for the first time in early 1971, when I was still working in social services. She was shown into my office by Elsa Drage. Drage is Norwegian for dragon, but she was the nicest one I had ever known. At that time Karin and I were both considerably younger – neither of us a day over thirty. Siren, her sister, was fourteen and it was because of her that Karin had come. She and her father had been searching for Siren for days. They had contacted the police, who had put her on the missing persons list, but as no unidentifiable body had been registered and there was nothing, initially, to suggest anything criminal had happened, they had not been able to make any promises. ‘But Dad’s got a bad heart,’ Karin said to me, ‘and my mother keeps fretting and fretting … that’s why I’ve come to you, to find out if you can do something.’

By ‘you’ she meant the social services’ Missing Children Department; and in fact we were able to help her. I found Siren three times in the course of the next two years. The first time I had to go to Copenhagen, the second to Oslo. The third she settled for our very own Haugesund. On the last occasion she was so debilitated by dope and sexual abuse that she couldn’t even be bothered to escape. A psychologist we used at the time, Marianne Storetvedt, did a great job on her; we got her into a young people’s psychiatric clinic, and when Siren was discharged six months later, she appeared to be fine again.

Out of gratitude for my efforts, Karin invited me for coffee and cake, and as I left we gave each other a hug. Seemingly by happenstance, we turned to face each other, and for a few seconds we kissed, as lightly and tentatively as teenagers doing it for the first time. However, I was still married to Beate, and I had no idea what Karin had up her sleeve. At any rate, nothing came of this until twelve or thirteen years later, when I had taken my leave of social services, set up my own private investigator’s office in Strandkaien, by the harbour, and when, once again, Siren had gone missing.

In the interim, I had been in regular contact with Karin, who was working at the National Registration Office. In a moment of exuberance she had promised me that, if I ever needed any help, all I had to do was ring, which I did. Often. Sometimes, perhaps, to excess. She had been married for a short while, but when I met her again in 1986, the marriage was over, after less than a year. She never told me what had happened, even though we stumbled into a relationship in the summer of 1987, without putting up much resistance, a relationship that had lasted until now – and was still ongoing, for as long as the doctors could keep her alive.

I leaned forward, studied the vibration under her closed eyelids, listened to her faint breathing, felt her pulse at the side of her neck. Her skin was soft and warm, as though she were merely resting. I ran a finger down her face, from her scalp to her pronounced chin and out to her cheek. Inside me, the pain and turmoil were bursting to be released.

Every year we had celebrated each other’s birthday in cosy intimacy, hers on the nineteenth of March, mine on the fifteenth of October. We had each kept our own flat, but the nocturnal visits had increased over the years. We had hiked through Rondane and Jotunheimen, staying in cabins; we had driven all over the south-western coastal region of Norway; and we had spent occasional long weekends in cities such as Dublin, Paris, Berlin and Rome. In Rondane, we had conquered the rocky mountain pass known as Dørålsglupen, both from the north and the south, and, a couple of days later, eaten trout sautéed with sour cream at the Bjørnhollia tourist cabin. In Jotunheimen we had slept in bunks at the self-service Olavsbu cabin before following the Mjølke valley down to Eidsbugarden and eating a proper gourmet meal in Fondsbu. In Dublin she had taken me somewhere that looked like the place where all books went when they died – the old library at Trinity College. In Rome, we had cuddled up on a bench on Mount Janiculum and watched the sun set over the city, before slipping through the side-streets down to Trastevere and enjoying a crepuscular repast at one of the restaurants there. But above all else we had been each other’s lodestar in our hometown, Bergen, the city between the seven mountains. For each other we had been somewhere to go for a hug when life became too depressing, when the National Registration Office was on the move again and the view from Strandkaien 2 was sadder than last year’s snow.

After I was shot in Oslo four years ago we became closer. She had jumped on the first plane and sat at my bedside for several days, as I was now sitting at hers. Later I had often thought it had not been so much the doctors’ efforts but her mental strength that had pulled me through. Had it not been for her, I might already be history. Things had come to such a pass a few weeks ago – at the back-end of summer – that I had said to her: ‘What if … if one sunny day I were to ask you to marry me, what would you answer?’ She had looked at me with an amused glint in her eye and said: ‘Tell me, Varg. Would you be proposing now?’ And I had answered: ‘Maybe …’ She had kissed me gently and whispered: ‘Were you to do it, I would probably take you at your word …’

Now she was lying here on her death bed. And it was all my fault.

2

Barely a week before, we had driven down to a quay in Nordhordland. We had parked in the space allocated, behind the large shop, but when we got out there was no one waiting for us.

Karin looked at me in surprise. ‘She said she would be here. It’s twelve o’clock, isn’t it?’

I nodded. ‘The clock strikes twelve and there’s no one to be seen. Send for Sherlock.’

She took out her mobile phone. ‘I’ll see if I can call her.’

While she was doing that I mooched around. The quay at Feste ran alongside Radsund, the main waterway north of Bergen for boats that were not too large. The Hurtigruten coastal cruises were further out. There was a black-and-white navigation buoy in the middle of the sound. On the other side there was a tall, dense spruce forest, something that might have been a bay or another sound, and beyond that we could glimpse some red-and-brown cabins.

Karin had got through. ‘Yes, we’re on the quay … Fine. We’ll wait here then.’ She glanced at me and rolled her eyes, then switched off the phone.

‘Everything OK?’

‘She’d forgotten the time. You wouldn’t believe it was her husband who had gone missing.’

‘Perhaps it’s not the first time.’

‘Well, I think it is. That’s why she’s asked for help.’

‘You know …’

‘Yes, I know you don’t do matrimonial work, but this is different. Take my word for it.’

‘There’s so much more of you that I would rather have.’

She sort of smiled; well, it wasn’t a great remark, but what else can you come up with on a chilly Monday morning in September with summer definitively on the wane and autumn beckoning on the horizon!

While we waited we nipped into the shop and bought a couple of newspapers. High in the gloom behind the cash till sat the shopkeeper, a friendly smile on his lips. He must have been wondering who we were and what our business was. This was one of those places where everyone knew everyone and a new face stuck out like a flower arrangement in a garage workshop.

The shop was quiet at this time of the day, and we were given a plastic mug of coffee each while we waited. I flicked through the newspapers. There were no world events hitting the front pages in the second week of September, 1998. Most of the coverage was given over to the Norwegian football team’s defeat to Latvia at Ullevål Stadium, the first at home for seven years and thirty-one matches and a sorry start to the upcoming European campaign. The Prime Minister was still off sick, and Akira Kurosawa had died in Japan. The eighth samurai had found his permanent place in the film history firmament.

After a while we went out onto the quay. Karin checked her watch again and peered north. ‘It’s not that far away.’

‘You’ve been here before, have you?’

‘Yeah, yeah, several times. Ranveig and I were at school together. For a few years we worked at the National Registration Office together, before she moved on.’

‘And – how long have they been married?’

‘Thirteen or fourteen years, I suppose it must be now. Mons has been married before. His first wife died – round here, in fact.’

‘Oh yes?’

She was about to expand on this when she was interrupted by the sound of a large, black Mercedes turning into the car park by the shop. The right-hand door opened, and a woman with short, dark hair stepped out and waved to us. Behind the wheel I made out the oval face of a man with slicked-back, steel-grey hair.

‘Oh,’ Karin said. ‘You came by car?’

The woman with the short hair hurried over towards her. ‘Yes, I …’ And the rest of what she said was lost because she gave Karin a big hug and her face was next to Karin’s cheek as she finished the sentence.

The man who had driven her was getting out of the car now, too. He was around sixty, tall with broad shoulders, wearing a brown leather jacket, blue jeans and robust, dark-brown shoes.

The two women released each other and half-turned to their companions.

‘You have to meet …’ Karin began.

‘This is …’ said the woman I assumed was Ranveig. They both paused, looked at each other and smiled.

By then I had joined them. ‘Varg,’ I said, holding out my hand.

She introduced herself in a solemn voice. ‘Ranveig Mæland. Thank you for coming.’

She was wearing a leather jacket too, but hers was short and narrow at the waist, and the tight jeans revealed athletic thighs and slim hips. Her face was pretty and heart-shaped, with quite a small mouth and large, dark-blue eyes. She had a single white pearl clipped to each earlobe. Beneath the lobes I noticed a vein throbbing hard, as though she were afraid of something.

‘Bjørn Brekkhus,’ her companion said, greeting first Karin, then me.

‘Varg Veum,’ I said, and added: ‘Bjørn the bear and Varg the wolf. The beasts of prey are well represented then.’

He shot me a look of mild surprise, then went on: ‘I’m a friend of the family.’

‘I couldn’t stand it out there … on my own, after Mons … Bjørn and Lise live here, on the mainland. Besides, Bjørn was Chief of Police in Lindås,’ Ranveig hastened to add.

‘Yes, but I’ve retired from the force now,’ he said. ‘Since June to be precise.’

She half-turned. ‘Shall we make our way across?’

Brekkhus nodded. ‘That was the idea, wasn’t it? I’ll just park properly.’

He got back in behind the wheel and moved the car a hundred metres or so to the marked parking spaces at the northernmost end of the quay area. I followed Ranveig and Karin in the same direction. Most of the boats were inside the harbour, safely moored and already semi-equipped for winter, as far as I could see.

The two women had come to a halt in front of an immense, white, glass-fibre ocean-going boat. A broad blue speed-stripe ran along the side of the boat to its registration number and name: Golden Sun.

Ranveig looked at me. ‘I gather that Karin has mentioned … the old case as well.’

I watched her, waiting. ‘You’re referring to …?’

She looked over her shoulder at me and the water. ‘Mons’ first wife, Lea. She disappeared out there as well.’

After her gaze returned, I said: ‘Disappeared?’

‘Yes.’

Brekkhus coughed at my side. ‘I was responsible for the police search, and I can assure you … we turned over every last stone.’

‘But …’

‘She was never found.’

‘Vanished without a trace?’

‘As if borne aloft by the wind.’

‘This we will have to hear more about.’

‘Yes, but …’ He motioned towards the boat. ‘Shall we cross the sound?’

‘Yes, OK.’

He turned to Ranveig. ‘Have you got the keys?’

‘Yes, here they are.’

She passed the keys to Brekkhus. He led the way alongside the boat, grabbed a painter and nimbly swung himself on board. Karin and I found seats at the very back. Brekkhus started the engine and glanced at Ranveig. She released the mooring ropes, he turned the boat in an arc northwards, and we were off.

No one said a word. Ranveig took a seat at the front, beside Brekkhus, as if he needed a pilot. I glanced at Karin. The return-look she gave me was inscrutable. When I held her eyes she pursed her lips into a little kiss and smiled cautiously. The wind caught her hair and raised it from her scalp. With one hand she gathered it behind her neck and focussed her gaze on the sound, where we were heading.

3

The cabin was situated on a rocky promontory facing the fjord. It was surrounded by spruces, almost certainly planted in the 1950s by Bergen schoolchildren on a re-foresting boat trip. Now the trees stood like dark monuments to a time when not only the mountains had to be clad but every tiny scrap of island skirted by the fjord. Accordingly, spruces lined long stretches of the Vestland coast. No one had thinned the striplings, and no one had cut down the trees, except the cabin-owners who had desperately tried to clear themselves a place in the sun. It looked as if they had given up here ages ago.

The path to the cabin wound upwards from the cement quay. To the north-east lay the islands of Lygra and Lurekalven. On the larger of these, in the middle, we could make out the slate-tiled roof of the new Heathland Centre. On the other, I knew there had been a medieval farm, which had been abandoned during the Black Death and remained uninhabited. Above us hung the sky, grey and heavy with rain, and the cortege making its way up from the sea was none too cheerful, either. We walked in formation: Ranveig Mæland and Bjørn Brekkhus in front, Karin and I right behind.

The cabin was a deep red colour, almost purple, with black window frames and facia boards. It was a classic 1940s cabin, erected either just before or just after the war. A west-facing annexe had been added later, and behind, bordering the forest, there was a structure that must have been an extension of some kind, painted the same colour as the main cabin, but with only one window and a plain wooden step up to the front door.

As we mounted the step, a light went on inside.

‘Ah,’ I said.

Ranveig craned her head round. ‘No, I’m afraid not. It comes on automatically, at random times. So that it looks as if someone is in.’

‘If only everyone was so sensible,’ Brekkhus said.

Ranveig produced a key and unlocked. She pushed the door open. Then gestured that we were welcome to enter.

We came into a classic cabin hall with small, woven tapestries of various dark colours, a large sea chart on one wall and a long row of hooks for an assortment of raincoats and weather-proof jackets on the other. There was no shortage of sailing footwear, walking boots and knitted socks, and in the corner facing us was a fibre-glass fishing rod, complete with line and lure, ready for use.

We followed Ranveig and Brekkhus to the end of the hall where we emerged into the cabin’s main room, which had a view of the sea and a kitchenette to the right. There was nothing luxurious about the furnishings. Traditional Norwegian pine furniture dominated. The TV set in one corner was between ten and twenty years old, the portable radio on the tiny bureau even older. The walls were decorated with a mixture of landscape paintings, nature photographs and the odd collage, the latter clearly put together by children. Tucked into one corner was a cabinet, which I imagined contained drinks, and along the wall to its right a bookcase so crowded with books that they were stacked higgledy-piggledy on top of one other without any obvious system. The electric radiators under the windows made a clicking noise, but the room wasn’t warm enough for us to take off our coats.

Ranveig went to the kitchenette, ran water from the tap and put a kettle on the stove. ‘I’ll brew us up a nice cup of coffee.’

‘Or two,’ I said.

Bjørn Brekkhus stood musing in the middle of the floor. He appeared uncertain what role to play, whether he should be the host, the guest or some point in between. Karin went over to Ranveig to ask whether there was anything she could do to help.

From the kitchenette Ranveig said: ‘Relax. It won’t take a second.’

I refrained from a witticism, despite the temptation. Besides, Brekkhus was much bigger than me. We each put a slightly under-sized chair by the pine table, which was scarred from years of use and covered with a red and green runner in the middle, on which sat a pewter candle-holder shaped like a Viking ship with a half-burnt candle inside, probably a present from such close friends that it would have been embarrassing not to display it.

I glanced up at the retired policeman. His steel-grey hair was cut in a short-back-and-sides fashion, but the combed-back fringe was long and parted over the rear part of his head to reveal his scalp. His oblong nose had a visible network of thin veins and resembled a sallow marine animal caught in a red net. His eyes were a glacial blue and his gaze was measured, as though he regarded everyone he met as potential suspects.

I snatched a sidelong glimpse at the kitchen. ‘Could you tell me a bit more about what happened to … Mons Mæland’s first wife?’

He puckered his lips in thought. ‘There’s not much more than I’ve already said.’

‘When did it happen?’

‘Early 80s, one hot August day. She used to go for a morning swim from the quay here, often on her own, but on the odd occasion she managed to entice Mons or one of the children to go with her. On this day she was alone. We found her dressing gown and a pair of slip-ons on the quay. When she didn’t return, Mons began to suspect some-thing was amiss. There were just the two of them out here, and he was dozing in bed. They had been fishing the night before. She used to make breakfast after the swim, but … as I said, on this day, she didn’t return, and when he went to look for her he just found her dressing gown and shoes.’

‘How old was she?’

‘About forty, if I’m not mistaken.’

Karin came in and put out mugs. Ranveig poured freshly brewed coffee from a white Thermos flask. ‘What are you talking about?’ she asked.

Brekkhus made a vague motion with one arm.

‘Lea?’

‘Yes.’

‘I don’t understand what she has got to do with this.’

‘Well, Veum was asking about her.’

I nodded. ‘I was just wondering what happened.’

‘The general assumption was that she drowned in a swimming accident.’

‘But?’

She shrugged. ‘It’s no secret that she had her problems. Periods of terrible depression.’

‘She was never found,’ Brekkhus repeated.

‘Did you know them at that point?’ I asked, focussing on Ranveig.

She flushed. ‘Not really. I was employed there later on. In the company.’

‘Your husband’s company?’

‘Yes.’

‘And what does it do?’

‘Property, investments. Mostly property. Developing industrial complexes, housing estates, cabin sites. Lots here in Nordhordland.’

‘And the name of the company is …?’

‘Mæland Real Estate AS. We just call it MRE.’

There was a slight pause, as a couple of us took the first swig of hot coffee. So far we had skated around the reason for our being here. But this was no chance meeting between friends or family. Nor was the cabin up for sale and we were not being shown around.

I considered it an opportune moment to tackle the matter head-on. ‘So your husband has disappeared?’

She had just lifted the mug to her lips. Now it hung in mid-air, in front of her gaping mouth. Her eyes widened a mite, and a helpless, hurt air came over her, which hadn’t really been there before.

She put down the mug, splayed her fingers out on the table, as if to support herself, and said softly: ‘Yes, two days ago.’

‘And you haven’t contacted the police yet?’

‘Present company excepted …’ She glanced fleetingly at Brekkhus, who was sitting with a mug in his hand and a pensive expression on his face.

‘Why not?’

‘I don’t think … I don’t know … When I rang Karin she told me about you, and what you do. I don’t think Mons is … if you see what I mean. We had a … a difference of opinion. Which became a little heated. Raised voices. The upshot was he left, grabbed his coat and slammed the door, and not long afterwards I heard the boat starting up.’

I nodded towards the window. ‘The one down there?’

‘No. We’ve got an Askeladden with an outboard motor.’

Brekkhus cleared his throat to attract attention. ‘It was found adrift to the south of Radsund on Sunday afternoon.’

‘I see! And he disappeared …?’

‘On Saturday evening,’ she said.

‘But …’

‘But the car was gone,’ Brekkhus said.

‘Uhuh?’

She took over. ‘His car was parked by the quay, where we met you. But now it’s gone.’

‘You both had a car?’

‘Yes, of course,’ she said in a tone that suggested she was talking to a young child. ‘Even at weekends he often had to travel because of his job, and I had more than enough to do here. At any rate, during the summer.’

‘All the indications are that he took it,’ Brekkhus said. ‘He may have moored the boat, and it worked its way loose or … well.’ He shrugged.

‘You’ve done some investigating?’ I asked. ‘Off your own bat?’

‘I made a couple of telephone calls. That’s about it.’

‘Well … in that case there are a number of leads, but … Karin probably told you, I don’t do, what in our branch we call matrimonials.’

‘Fine, but this isn’t,’ Ranveig said. ‘You do missing persons, don’t you?’

‘Yes, as far as they go. But rarely of this vintage.’

‘Is he too old, do you mean?’ She glowered at me.

‘No, no, please let me explain. What I meant was … the missing persons I am asked to find are usually young people with serious problems. What was your problem?’

‘Problem?’

‘You said you’d had a row. Or a difference of opinion, as you called it. Could you tell me what it was about?’

She licked her lips. The tip of her tongue was small and pink, like a naked little animal, it poked its head out, took fright and quickly retreated. ‘It was a family … matter.’

‘Mhm?’ I watched and waited.

‘You don’t need all the intimate details to find him, do you?’

‘Not everything maybe, but a rough sketch would help. If you want me to find him, that is.’

‘If I want …! What do you mean by that?’

‘The more you can tell me, the easier it will be.’

Karin and Bjørn Brekkhus sat in silence, listening now. What Ranveig had to tell us was important. She took a mouthful of coffee and pulled a face before starting: ‘Everything centres around Brennøy.’

‘The island in …?’

‘The municipality of Gulen. Quite a way out. About as far as you can go before you hit the sea.’

‘And what has your husband got to do with Brennøy?’

‘At the end of the 80s he bought a large plot there. Nothing to write home about. A few wind-blown cliffs and rocks to the north of the island. But he didn’t pay much for it. An investment for the future, he said at the time.’

‘That was what most people said at the time.’

‘Yes, I know. The worst yuppie period. But Mons was looking further ahead.’

‘By which you mean …?’

‘Renewable energy. He could visualise the rocks being … the perfect place for a wind farm. The technology was being developed. In Denmark and several other countries the first wind farms were already up and running and there were several more on the drawing board. Here, there were plans for wind turbines in Northern Trøndelag and in Nordland. Mons was convinced that Vestland would follow suit, above all with a view to making money after the seabed had no more oil to offer.’

‘A forest of wind turbines along the whole coast? Passengers on the Hurtigruten cruise ships have got something to look forward to.’

Her eyes flashed. ‘Exactly! That’s like listening to his daughter, Else. Green in every respect.’

I arched my eyebrows. ‘Is that what you were arguing about?’

‘You could put it like that, yes. Else was the apple of his eye, of course. She had just turned four when she lost her mother and there had been a few pretty awful experiences before that, in the bargain.’

‘Really?’

‘Yes. Anyway … Mons had started to listen. Something of a sea-change, I can tell you. Generally he used to, well …’

‘Even die-hard socialists can go green in their old age.’

‘Must be with mould then. Anyway, Mons was never a socialist, I can promise you that.’

‘No, it doesn’t sound like it, but …’

‘But, if I might be allowed to finish what I was saying …’ She adopted a sarcastic expression.

I nodded, and opened a palm.

‘It was two against two. Mons and Else on one side. Kristoffer and me on the other.’ She answered my question before I could ask. ‘Kristoffer’s his son. He’s the one who will take over when Mons retires.’

‘I see. But who is the largest shareholder in the company?’

‘That’s Mons. Still.’

‘So he could do what he liked, then?’

She sent me a desperate look. ‘Why do you think we disagreed?’

‘Fine, but … Was that all? And this – what shall I call it? – ecological disagreement led to Mons slamming the door and leaving? And since then no one has seen him?’

‘Yes.’

‘No other … disagreements?’

‘Like what?’

‘Well … most marriages are like waters littered with submerged rocks. You never know when you’ll hit one.’

‘We didn’t have any other disagreements.’

‘If you say so, I’ll have to believe you.’

‘Yes, you will, actually.’

‘I assume you’ve tried to ring him? Does he carry a mobile phone on him?’

She glanced at Brekkhus. ‘Yes, but there’s no answer. He must have switched it off. Or else …’

I paused for a moment to follow her eyes. ‘Perhaps you also made a couple of calls regarding this matter, did you, Brekkhus?’

He cleared his throat and looked ill at ease. Stiffly, he said: ‘No activity on his phone has been observed since Saturday afternoon.’

‘Nothing since he disappeared, in other words?’

‘That sounds serious,’ Karin said.

Brekkhus shrugged. ‘It might be. But – as Karin said – he might have switched it off.’

‘Or he might have dropped it in the sea as he left,’ she added. ‘He could have thrown it into the sea for all I know. He could get into quite a temper.’

‘Really? Could he be violent?’

‘No, no, not so that he would hit anyone. Not at all. But he could take his temper out on … physical things. Once when we were quarrelling he slung his mobile on the floor and stamped on it so hard it broke.’

‘Expensive habits. But he didn’t just go straight home, did he?’

‘No. I checked that, of course. I got Kristoffer to pop up, but there was no one at home.’

‘Where do you live in Bergen?’

‘In Storhaugen.’

I had taken out my notebook, and she gave me the house number. Then I jotted down the home telephone number, Mons Mæland’s mobile number and hers.

‘And Kristoffer, where does he live?’

‘In Ole Irgens vei.’

‘Family?’

‘Has he got any? – a wife and two children, although I can’t see what that’s got to do with this case.’

‘It hasn’t got anything to do with the case. It’s just to get a picture. The daughter?’

‘Else lives in Kronstad – in a student collective,’ she added with a sarcastic undertone.

‘And the address?’

‘Goodness me! Ibsens gate. But I’d rather you didn’t bother them with … this.’

‘They know about it though?’

‘I told you I asked Kristoffer to pop home to see if Mons was there, but, as I said, there’s no need to bother them.’

I looked at her. ‘Their father has gone missing, and you don’t want me to bother them with this?’

‘What I mean is they can’t know anything anyway.’

‘No? But it may turn out that … It may have been quite traumatic when they lost their mother. Else was only four years old, didn’t you say?’

‘Yes.’ She looked at Brekkhus. ‘And Kristoffer must have been, well, twelve, wasn’t he?’ He nodded, and she continued: ‘They don’t want to talk about it.’

Brekkhus coughed. ‘It was a shock for them, of course. But they weren’t here when it happened, fortunately.’

‘Where were they then?’

‘Well … in fact I can’t remember, but I think Kristoffer was on a hiking trip with a friend and his family, and Else had a sleep-over at a friend’s.’

‘In other words, the parents had a kind of free weekend. With a catastrophic outcome.’

‘Yes, that’s about the long and short of it.’

I turned my attention to Ranveig again. ‘How’s your relationship with your step-children?’

She hesitated for a moment before answering. ‘Quite … run of the mill. I’m not exactly the evil stepmother of fairy-tales, if that’s what you’re suggesting.’

‘I’m not suggesting anything at all. I’ve just noted that you don’t want to bother them with this disappearance …’

She sighed. ‘Of course you can talk to them. I didn’t mean it like that. But they have their own lives to lead. I can’t imagine they have anything to contribute. That was what I meant.’

I nodded. ‘Fine. So where do you think I should begin? Where are the company offices?’

‘In Drotningsvik. But …’

‘Perhaps you don’t want me to bother them, either?’

She rolled her eyes. ‘You’ll see Kristoffer there anyway. What I was thinking was … if anything should leak out about Mons being … missing. It’s a sensitive line of business.’

‘Mine, too. Especially when I’m not given anything to work on.’ I considered the matter. ‘What about Brennøy? Could he have gone there?’

She studied my face, unsure. ‘It’s just a plot of land. No houses.’

‘But that was what the row was about. He may have gone there to see the place with fresh eyes. Maybe see if he agreed with you after all. You and Kristoffer.’

‘Mm …’

‘There’s another question I have to ask you.’

‘Right.’ She gazed at me with apprehension, and I could feel a chill in her eyes.

‘Have you any cause to believe … Is it possible that there might be someone else?’

She heaved a deep sigh. ‘If there had been, well, fine – almost. That at least would have been an explanation. Somewhere to start looking. But no, I’m afraid I have to disappoint you, Varg. I have no cause to believe any such thing.’

‘Disappoint? I don’t take that kind of case, so …’

A sudden silence descended over the gathering. I let my gaze wander from Ranveig Mæland to Bjørn Brekkhus – both had equally glum faces – and on to Karin, who also looked resigned.

As if to rid me of any last doubts, Ranveig said: ‘Of course you’ll be paid for your work. I can transfer the money as soon as I’m home. Just give me your account number and a figure.’

She jotted them down without any indication of an impending nervous breakdown. Then looked around. ‘Everyone got what they need, coffee-wise?’

‘Yes, thanks,’ came the motley chorus from around the table.

‘I’ll just rinse the cups. Then we can go.’

‘I can help you,’ Karin said.

I caught Brekkhus’s eye. ‘Could we go outside for a moment?’

‘Dying for a fag?’ he said with an amused glint.

‘I don’t smoke. But there was something I …’

He nodded and got up, and we went out together. Ranveig watched us leave. She looked as if she would have liked to join us. What did I know? Perhaps she was dying for a fag herself?

4

It had begun to rain. The sea mist lay low over the countryside, and the island of Lygra had vanished in the grey haze. The heavy, vertical rain hit the ground with immense force. We stood in the porch to stay dry. Beneath us the boat bobbed up and down by the quay like a gluttonous gull weighed down with belly fat.

Brekkhus glanced at me expectantly.

‘Didn’t look like Ranveig placed much importance on what happened to Mæland’s first wife, Lea, did it.’

‘No.’

‘Could you fill me in with a few more details?’

He rocked his head from side to side. ‘There’s not a lot more than I’ve already said, and … well, I can’t see how it can have any bearing on this case.’

‘I’ll be the one to judge that.’

‘I’ve said that sentence many times myself.’

‘So you know how necessary it is. Well …’

His eyes wandered down to the boat, the quay and the small inlet. ‘As I said … They found her dressing gown and shoes down there. None of the boats was missing. Everything pointed to a drowning accident.’

‘But Ranveig mentioned something about bad bouts of depression.’

‘Yes. She’d had what doctors call post-natal depression. Both times.’

‘How serious was it?’

‘After the last round she was admitted to hospital – for a lengthy period.’

‘I see. So suicide wasn’t so unlikely …’

‘No, it wasn’t, which only underlined the gravity of the situation.’

‘But the body wasn’t found.’

‘No, but the currents round here can be pretty dramatic.’

‘Yes, I know. But most bodies float to the surface at some point, don’t they?’

‘Of course. Over the years that followed we had reason to go back to her file on several occasions. In fact, the very next month, but the body we found was that of a much younger woman and there was no birthmark.’

‘Birthmark?’

‘Yes.’ He automatically touched the small of his back. ‘Lea Mæland apparently had a birthmark just here. Star-shaped we were told. I’d never seen it personally.’

‘And of course after a while it would be useless as a distinguishing mark.’

‘That goes without saying. Bodies that have been in the sea for more than a month … pretty drastic things happen to them and they’re often eaten.’

‘And still people call crab a delicacy.’

‘Yes, but then we don’t eat the crab’s stomach, do we.’

‘No, thank bloody Christ for that, as Martin Luther would say.’

He looked at me in surprise, a common reaction to townies’ attempts at humour around these parts.

‘Was Mons Mæland taken in for questioning during this case?’

‘We had to question him as a matter of form, but as Mons and I knew each other, someone else at the station had to take responsibility for the investigative side of the case.’

‘And the conclusion was …?’

‘No grounds for suspicion. He’d been fishing in the Lure fjord the night before and came home late. By then Lea had already gone to bed.’

‘No marital differences at the time?’

‘Not as far as we could gather, no.’

‘How well did you know each other, you and Mons?’

‘We’d met a few times when we were young, but it wasn’t until later … We became friends when we started taking our holidays here. I live over there.’ He pointed across the sound towards Lygra.

I was about to say something else when the door behind us opened and Karin came out. ‘Why are you standing out here?’

‘We’re waiting for Noah,’ I said.

She looked anxiously up at the heavens. ‘Yes, looks like the sluice gates have opened.’

‘And there’s no sign they’re going to be closed any time soon.’

Ranveig appeared behind her. ‘I was wondering if you wanted to see the annexe, Varg.’

I glanced towards the corner of the house. ‘Yes, why not? Any special reason?’

‘That’s where he has his office when we come here.’

‘OK, let’s take a peek,’ I said, stepping into the rain and pulling my jacket over my head as I dashed towards the small annexe we had seen from the sea. The others followed, both Ranveig and Karin having the foresight to carry an umbrella, Brekkhus the mettle to set off bareheaded, with water streaming down his neck. Within seconds the rain had flattened his hair, so much so that it looked painted on.

Ranveig was there first with the bunch of keys, she quickly found the right one and let us in. We ran inside shaking the water off us like stray dogs sheltering from a cloudburst.

She switched on the light and we looked about us. The annexe consisted of one room. A high table had been placed in front of the window. On it there were piles of paper, documents, writing implements and a stack of floppy discs. Along one wall there was a bunk bed, and in the corner an old-fashioned washstand in front of a small mirror. On a slim bureau there was a kettle, some mugs, a jar of instant coffee and a couple of packets of tea: English breakfast in one, green tea with lemon in the other.

‘No computer?’ I asked.

‘He uses a laptop … there.’ She pointed to the empty space between the piles of paper.

‘But he’s evidently taken it with him?’

She nodded. Brekkhus sent me an eloquent look.

‘Is there anything as advanced as an internet connection out here?’

‘No, of course not. But it wouldn’t surprise me if there was one day.’

‘So it was more like a portable typewriter, was it?’

‘Yes, I suppose so. But he could bring a whole heap of papers with him and sit working on them until he took them back home – or to the office – when the weekend was over.’

I went over to the desk and placed a hand on one pile. I looked at Ranveig. ‘May I …?’

‘By all means!’ She extended a hand.

I flicked through the top sheets of both piles. They were mostly job-related documents, which didn’t mean a lot to me. There were several property projects, among them a summer cabin to the north of Øygården and a major industrial venture in Gulen. The latter appeared to be connected with renewable energy: wind or wave power. I noticed one signature seemed to keep popping up. The name was Jarle Glosvik.

The document on top of the pile to the right was a letter adorned with a dynamic, blue logo, a windblown N merging with a P, furnished with the explanatory subtext, Norcraft Power. In the letter, which was addressed to Mæland Real Estate AS, attn. Mons Mæland, the signatory, Erik Utne, confirmed that the planned survey of Brennøy would take place as arranged on the ninth of September at twelve thirty. The company would be represented by a delegation consisting of four people, led by Utne himself.

‘He’s going to Brennøy on Wednesday,’ I said, holding up the sheet.

Ranveig took it and read. Then she nodded. ‘Let’s hope he gets there, eh?’

‘Yes … do you mean we should let the matter rest until then?’

‘No, I don’t mean that. But …’ She searched Brekkhus’s face, as if hoping for support from him.

‘What Ranveig means to say is that Mons probably should be at that meeting. If he isn’t, the whole deal could go down the plug hole.’

‘So if Mons doesn’t turn up …’

She met my eyes again. ‘Talk to Kristoffer,’ she said in a low voice.

‘There’s a lot to suggest that I should,’ I said. ‘Can I take this with me?’

She nodded.

I found nothing else of immediate interest on his provisional desk. I was given permission to open the drawers of the slim bureau as well, but all I found was a small collection of envelopes of various formats, several floppy disks with labels describing the contents, all of a work nature. Going though each of them would take time and, judging by their appearance, be of doubtful significance. In the bottom drawer I found something which gave me a stab of longing for my own office: half a bottle of aquavit, half full. But it wasn’t my favourite brand. This was Danish and had to be drunk chilled.

We left everything as it was. I cast a final glance around before leaving. On the wall there was a solitary landscape painting of the kind you inherit from parents with a simple taste in art. I had a couple myself, of Sunnfjord, where my father grew up, neither exactly masterpieces.

‘They used this place as living quarters while the cabin was being built, I suppose. Just before the war, I think it was,’ said Brekkhus.

‘His parents?’

‘No, no. Mons and Lea bought this when Kristoffer was small. Early 70s it must have been.’

‘I see.’

Then we left. The rain had let up. The light haze lay like a silk blanket over the countryside. High above us we glimpsed a white orb, the sun, like a beating heart, , still not strong enough to burst through.

While Ranveig locked the cabin I stood slightly apart with Brekkhus. ‘Tell me: What do you personally make of this disappearance?’

‘Personally?’

‘Yes, as a good friend. Do you think something has happened to him?’

Neither Ranveig nor Karin was within earshot. Nonetheless, he lowered his voice. ‘If you ask me, I think he’ll turn up again. My guess is he went underground – if I can put it like that – to avoid the unpleasant confrontation there might well be on Brennøy at this survey on Wednesday. Or …’

‘Yes?’

‘Well … probably to avoid any improper attempts at persuasion.’

‘Are you thinking bribes?’

‘For example. But it’s impossible to know, of course. Only time will tell.’

‘And the mills of time grind slowly. As in Lea’s case.’

‘Well, the case was declared closed after a few years.’

‘She was declared dead?’

‘Yes.’

He had no more to add. Ten minutes later we were on board the boat and heading back. Brekkhus steered us safely into Feste, where a boat was moored at the quay taking on diesel, with the assistance of the helpful grocer, who checked us over one last time as we got into our cars. He was probably wondering what we were up to on the island. After all, not a lot happened in this area of Nordhordland on Monday mornings in September.

Before we went our separate ways, I said to Ranveig: ‘Could you ring Kristoffer and warn him I’ll be calling?’

‘Will do,’ she answered with a brief smile. ‘Good luck, Varg. I hope you find him before …’

‘Before what?’

‘Before the meeting on Wednesday.’

I nodded and smiled encouragingly, but even before I had got into the car the smile was gone and my mind was already churning. Or before it’s too late, I said to myself.

‘God knows how I’m going to find him with so little to go on,’ I said to Karin.

As we negotiated the narrow, winding road to Seim and then took the main road from Mongstad south to Bergen, I barely listened to what she said.

Before we had reached the roundabout at Knarvik my mobile rang. I gave it to Karin to answer. After a few words she looked at me. ‘It’s Ranveig. Kristoffer’s expecting you at half-past three. Is that OK?’

I looked at the clock in the car. It read 14.10. ‘So long as there are no unforeseen hold-ups … Tell her I’ll be there.’

She confirmed the arrangement, chatted for a while and then rang off.

As we drove onto Nordhordland Bridge the sun was beginning to break through the cloud. Stout beams of white sunshine fell diagonally across Byfjord, the contours of a colossal construction, erected to hold in place the safest source of energy known to man, provided that it kept burning.