Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

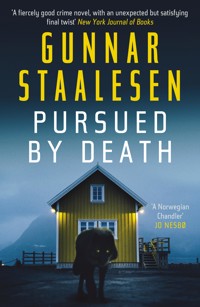

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Varg Veum

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

When Bergen PI Varg Veum becomes involved in the disappearance of a young activist, he comes up against one village's particular brand of justice … The international bestselling, critically acclaimed Varg Veum series returns… `As searing and gripping as they come´ New York Times `One of my very favourite Scandinavian authors´ Ian Rankin `The Norwegian Chandler´ Jo Nesbø When Varg Veum reads the newspaper headline 'YOUNG MAN MISSING', he realises he's seen the youth just a few days earlier – at a crossroads in the countryside, with his two friends. It turns out that the three were on their way to a demonstration against a commercial fish-farming facility in the tiny village of Solvik, north of Bergen. Varg heads to Solvik, initially out of curiosity, but when he chances upon a dead body in the sea, he's pulled into a dark and complex web of secrets, feuds and jealousies. Is the body he's found connected to the death of a journalist who was digging into the fish farm's operations two years earlier? And does either incident have something to do with the competition between the two powerful families that dominate Solvik's salmon-farming industry? Or are the deaths the actions of the 'Village Beast' – the brutal small-town justice meted out by rural communities in this part of the world. Shocking, timely and full of breathtaking twists and turns, Pursued by Death reaffirms Gunnar Staalesen as one of the world's greatest crime writers.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 413

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

iWhen Varg Veum reads the newspaper headline ‘YOUNG MAN MISSING’, he realises he’s seen the youth just a few days earlier – at a crossroads in the countryside with his two friends. It turns out that the three were on their way to a demonstration against a commercial fish-farming facility in the tiny village of Solvik, north of Bergen.

Varg heads to Solvik, initially out of curiosity, but when he chances upon a dead body in the sea, he’s pulled into a dark and complex web of secrets, feuds and jealousies.

Is the body he’s found connected to the death of a journalist who was digging into the fish farm’s operations two years earlier? And does either incident have something to do with the competition between the two powerful families that dominate Solvik’s salmon-farming industry?

Or are the deaths the actions of the ‘Village Beast’ – the brutal small-town justice meted out by rural communities in this part of the world.

Shocking, timely and full of breathtaking twists and turns, Pursued by Death reaffirms Gunnar Staalesen as one of the world’s greatest crime writers.

ii

iii

Pursued by Death

GUNNAR STAALESEN

Translated by Don Bartlett

v

vi

‘Wild salmon are either fighting fit or dead, but our farm-bred salmon are like a stressed-out, overweight man who suddenly has to sprint for the bus.’

—Simen Sætre & Kjetil Østli:The New Fish, Spartacus, 2021 (translation by Don Bartlett).

Contents

1

It all started the day the Sogn og Fjordane police took it upon themselves to confiscate my driving licence.

It was a sunny day towards the end of September. After my trusty Toyota Corolla had been forced off the road and wrecked on Sotra island in January, I bought myself another car: same brand, previous year’s model, in an equally discreet colour – as grey as the sky above Bergen was for the majority of the year.

I was coming from a job in Nordfjord, where I had done my diplomatic best to resolve a forty-year-old boundary dispute that started on New Year’s Eve 1963, when neither of the two neighbours had been entirely unaffected by home-made hooch. As so often, it was the next generation who were banging their heads against the wall, trying to agree on a two-state solution a Middle East peace negotiator would happily accept. Whether I had succeeded or not, time would tell. I had my misgivings, as the heart of the dispute concerned a man with family connections in the area who was relocating from the eastern side of the country, and who had a burning desire to build his cabin on the bit of the property that had a view but encroached on his neighbour’s land by somewhere between twenty and eighty centimetres. Now I was on my way back to Bergen with a contract and the promise of an imminent fee in my inside pocket, national-romantic music on the car radio and countryside that was filling its lungs with long, drawn-out breaths around me: out by scenic Sandane village; in through Våtedalen valley; out again as Lake Jølstra unfolded on the left.

I took all the time I needed to digest everything. At regular intervals I glanced at my rear-view mirror. A large, white animal-transport vehicle had been on my tail the whole way from the ferry terminal in Anda, without showing the slightest sign of wanting to overtake me. 2

As I was approaching Vassenden, I felt I needed a break and a cup of coffee. I indicated by Jølstraholmen, where there was a camping site and a café. I had hardly swung in to park in front of the café when a car with a flashing blue light on the roof drove in so close to me that we could have got engaged. I gazed over and met the eyes of a uniformed policeman, who motioned from the passenger seat that I should buzz down my window.

I saw no reason to refuse, and the first thing he said to me, in nynorsk, was: ‘Are you on medication or what?’

I looked at him in amazement. ‘What?’

He studied me for a few more seconds. Then he pointed to the car park further ahead. ‘Drive over there and park.’

I did as he said, and the female officer I glimpsed behind the wheel followed suit.

The policeman got out of their car, strode with determined step over to mine and leaned over. ‘We’ve received a number of phone calls about a motorist weaving in and out of traffic and generally driving dangerously.’

The man spoke a polished version of nynorsk, the official Norwegian of the Sogn and fjords county, as opposed to the bokmål of Bergen, but I didn’t find him difficult to understand. The content of what he said, however, was another matter. ‘What are you talking about?’

‘It looks as if we’ll have to confiscate your driving licence.’

Still I found it hard to grasp what he meant. ‘Based on what evidence?’

‘A number of phone calls. Let me see your vehicle-registration card and your driving licence, please.’

‘There must be some mistake. It cannot be my car.’

He started to bristle. ‘Registration card and driving licence please!’

His female colleague had got out of the car, too. She was standing with what I could see was a breathalyser in her hand. 3The policeman examined my cards and assiduously studied my face before returning them, as though he suspected that I was posing as someone else.

‘Varg Veum?’ he said, and I nodded. ‘Strange name.’

‘And yours is?’

‘Joralf Smalabeit.’

‘And you think my n—?’

He interrupted me. ‘We’ll have to run a breathalyser test on you.’ He nodded to his colleague. ‘Sylvi.’

I politely asked her what her surname was, opened my mouth obediently and blew as hard as I could into the plastic tube she placed between my lips. For an instant our eyes met. In hers, I discerned no obvious sympathy. She took the tube out, waited for five seconds before checking the screen and almost sounded a little disappointed when she reported back: ‘Zero point zero zero.’

Joralf Smalabeit regarded me with a thoughtful expression. Then he turned to Sylvi. ‘Has the complainant parked up?’

She nodded.

‘Have a word with him.’

I watched her leave. ‘I assume the misunderstanding will be cleared up then.’

‘Doubt it. The vehicle reg is correct.’

For a few seconds my head seemed to whirl. It was many years since I had read Franz Kafka’s The Trial, but all of a sudden it was as though I recognised the situation. ‘My vehicle registration?’

He looked at me with the same serious expression as before. ‘Let’s have a few personal details then, shall we. I’ve got your name. Profession?’

I sighed. ‘Private investigator.’

‘What did you say?’

‘Private investigator.’ 4

His eyes became even more suspicious. ‘Not a former colleague, I trust?’

‘Depends on how you define colleague.’ I let him reflect on that. ‘Not from the force, if that’s what you were afraid of.’

‘I’m not afraid of anything.’

‘Good to hear. Sleep well at night, do you? Dream about solving life’s mysteries from the passenger seat of a VW Up?’

‘Where have you come from?’

‘Nordfjord.’

‘In a private capacity or…?’

‘No, doing my job.’

‘Which in this case means…?’

‘I can be anywhere. Have you heard about the Palestinian conflict?’

‘Eh?’ But he was interrupted by the return of Sylvi.

They moved further away. In the side mirror I could see her reporting back, waving her arms in wide circles and continually pointing in my direction.

Joralf Smalabeit came back to me. ‘You stay here. We’re going to call the police solicitor.’

‘Which one?’ I mumbled.

‘And don’t try to leg it, or we’ll have to arrest you.’

I arched my eyebrows in what I hoped was a suitably ironic way. But when they returned a few moments later, it turned out that the police solicitor, he or she, was not on my side either.

‘We’ve decided to confiscate your driving licence. Do you consent?’

‘No, I do not. You can be dead sure about that. Does that help?’

‘No. But it does mean we’ll have to present the confiscation order to the district court within three weeks.’

‘And in the meantime, you’ll treat me to a stay at one of the camping cabins here in Jølstraholmen and pay me for the work I’ve lost?’ I didn’t say that the latter would cost them considerably less than the stay. 5

He smirked. ‘We’ll drive you to the police station in Førde and do a formal interview there. If you can budge over onto the passenger seat, I’ll take the wheel.’

‘Your driving licence is valid, is it?’

‘You can cut out the jokes. You’re wasting your breath. They won’t help you one tiny little bit.’

‘No, I can sort of see that. That’s the fate of us stand-up comics. One day no one will laugh at us anymore. You do know the way, I take it?’

2

I had been to the police station in Førde, the county town, before, in the mid-eighties, in connection with a case involving a young lad known as Johnny Boy. But the station had moved since then. Now it was in a street spelt Fjellvegen; it didn’t have anywhere near as nice a view as there was from the Fjellveien in Bergen. On the other hand, they did have a solid mountainside at their back: Hafstadfjellet, Førde’s answer to Ålesund’s Sukkertoppen mountain.

Here, Joralf Smalabeit handed me over to a young policewoman. And after that, I didn’t see either him or Sylvi again. They were probably already racing around the dangerous Vestland roads on the lookout for more big-time criminals with animal-transport vehicles in their wake. It transpired quite quickly during the interview that the huge number of phone calls complaining about my driving emanated from a single person – the man who had been behind the wheel of the aforementioned vehicle. This was more than enough to suggest either that it was him the police should have been breathalysing, or that he had been hallucinating, but they had kindly failed to follow this up.

The young officer who interviewed me was otherwise pleasant company and polite enough. She introduced herself as Solrun Storehaug and asked me to give my account of the day’s events. While I talked, she busily took notes. When I had finished, she referred to the conversation with the man in the vehicle behind me. In his judgement I had been holding a mobile phone the whole time without regard for road conditions; he had seen me almost collide with oncoming traffic a few times, almost leave the road and commit a variety of other road-traffic misdemeanours; in other words an experience of our shared drive from Anda to Vassenden that was totally at variance 7to my own. I passed her my phone and told her that she was welcome to check my chat log. The phone had been as silent as a meditating monk throughout the whole journey. The only people I had listened to had been Edvard Grieg and his composer colleagues on the car radio. She noted this down too, but opted not to check my phone.

‘The police lawyer in Florø has agreed that we should confiscate your driving licence,’ she said.

‘And his justification for that is…?’

She inclined her head and looked at me. ‘All the complaints we’ve received about your driving.’

I could feel indignation rising inside me. ‘All the complaints! How many were there?’

‘I’m afraid, there’s nothing I can do about this. It’s the lawyer’s decision.’

I made a resigned gesture. ‘So what do I do now?’

‘We’ll impound your car. Your driving licence will be sent to the lawyer. You’ll be hearing from us. As you haven’t consented to the confiscation, the case will be brought before the court within three weeks at the latest.’

‘And how do I get to Bergen?’

‘I’ll point you in the direction of the bus station.’

‘Can I ring my solicitor?’

She pushed my phone back across the table. ‘By all means.’

I got Vidar Waagenes on the line. He chuckled when he heard what the call was about. ‘This is not the first time I’ve heard this sort of thing from Sogn og Fjordane,’ he said. ‘I’m sure it didn’t help that you’re a Bergensian.’

‘Can you help me?’ I asked impatiently.

‘Not right this minute. It will take a few days at best. Perhaps an appearance in Førde court in three weeks. Drop by when you’re back in town.’

‘Back in town? I have to catch the bus.’ 8

He chuckled again. ‘You’re not the first to have undertaken this journey, Varg. Regard it as a challenge.’

‘OK,’ I said, ringing off.

Solrun Storehaug looked at me with something approaching sympathy in her eyes. Then she told me how to get to the bus station.

The next bus to Bergen left in two and a half hours. I killed an hour and a half eating an excellent lunch at somewhere called Pikant, by the banks of the Jølstra, and sat in the bus-station waiting room for the last hour.

There weren’t many passengers getting on the bus from Ålesund to Bergen this afternoon. I counted twelve apart from myself. Some of them were travelling alone; several were school age. An elderly couple sat down at the front; they were going to Vadheim. Two young women in hiking gear had brought along some broad rolls of canvas, which they stowed in the luggage compartment at the bottom of the bus. They brought their small rucksacks inside. I looked up as they passed me down the aisle. They had that featureless appearance good-looking young people have before life leaves its marks on them. One had blonde hair tied into a ponytail; the other girl’s hair was dark, in a short, practical style that used to be called, and perhaps still is, a summer haircut.

A man in his fifties wearing a cloth cap and coat bore such a lugubrious facial expression that I put him down as a condolence-card salesman. The similarly aged buxom woman who sat down a couple of seats behind him, chatting away on her phone and giggling, was unlikely to be a potential customer of the salesman. It turned out that she would keep talking through all the mountain bends on Halbrendslia and deep into Langeland before considering the time appropriate for a rest.

By then I was well engrossed in the novel I had bought in the kiosk at the bus station – a crime thriller that took place in 9Iceland. An elderly man had been found murdered in a cellar in Reykjavík, and among the evidence the police discovered at the crime scene was a photo of an old grave where a child was buried. The story went back a good number of years in time to a locale in which, in many ways, I felt quite at home. At least it distracted me from my annoyance at having my driving licence confiscated.

On the ferry across Sognefjord, between Lavik and Oppedal, most passengers got off the bus to stretch their legs and go to the toilet, or to buy a cup of coffee, a pancake or a hot dog in the lounge. Eeyore was left on his own. The buxom woman stood on the deck and had started another telephone conversation, this one slightly more impassioned than before. The two young women remained on the deck too, chatting during the crossing; they had returned to their seats before I made my way back from the lounge, the taste of bitter coffee lingering in my mouth and my bad mood on the rise again.

We were leaving Sogn og Fjordane behind us and driving into Hordaland county when the driver pulled into the verge and came to a halt by a bus-stop sign. At the crossroads, down a side road, there was a two-tone, brown and beige VW minibus – a vintage model, the type manufacturers call a camper van. You saw a lot more of them in the seventies and eighties than this side of 2000.

In front of the camper van stood a young man with longish, dark-blond hair. He had a sharp profile with an aquiline nose that made him easy to remember. The two girls alighted from the bus. The dark-haired one ran over to him, gave him a warm hug and stood close to him while the girl with the ponytail collected the two canvas rolls from the luggage compartment. Holding them with some difficulty, she stood beside the road and said something to the other two. They disengaged themselves and came over to her. But by then the bus had already set 10off for the first of two long tunnels that would take us through Masfjorden and Lindås towards Bergen.

The following week, I saw one of the young people again – in a photo in the newspaper. It was the man with the aquiline nose, beneath the headline: ‘YOUNG MAN MISSING.’

3

The weather had been changeable for a while, like my mood, which varied according to the progress of the case against me.

Vidar Waagenes had called the police lawyer in Sogn og Fjordane on Wednesday morning. He brought me up to date on the phone: ‘She’s going to review the case and email us the reasoning behind the confiscation of your driving licence.’

‘And how long will that take, do you think?’

‘She promised she’d have a look at some point during the day.’

Nevertheless, it was Thursday afternoon before Waagenes emailed me those reasons. I hit the roof. Once again, the email described how I’d almost had collisions, almost swerved off the road, almost had accidents – as reported in a series of phone calls to the police.

I phoned Waagenes. ‘And how many people rang in?’

He still thought this was a chuckling matter. ‘Well, it was this animal transporter who was on your tail from Anda to Vassenden.’

‘Exactly. Why the hell didn’t he honk his horn or flash his lights when he saw all these incidents? I remember his vehicle very well. I kept checking to see if he wanted to pass. But he clearly didn’t. He must have been sitting up in his raised seat laughing himself silly at the lunatic in front of him – his hilarity only briefly punctuated by telephone calls to the police.’

‘Yes, it’s a bit strange.’

‘Tell me, does this nutcase have a name?’

He did. ‘Atle Helset.’

‘Well, would you believe it?’

‘Does the name mean something to you?’

‘I told you I’d been to Nordfjord to mediate in the case of a boundary dispute that’s been going on for years, didn’t I?’

‘You did.’ 12

‘Well, the man who had to give way in the case is called Zacharias Helset. A mature gentleman, who would not drive round, transporting animals. But he’ll have younger relatives, I suppose.’

‘Interesting, Varg. You may well have a point. In which case perhaps we should consider reporting him for acting under false pretences?’

‘But then we’ll have to go to Førde. I don’t know if I can be bothered. The most pressing thing for me is to get my licence back as quickly as possible.’

‘Fine. You decide. We can come back to it. I’ll call Florø and inform the police lawyer about the new development. You’ll be hearing from me.’

I did, after roughly five minutes. The police lawyer was off sick, but was expected back at work on Monday.

I hit the roof again. ‘What! So that means … ’

‘We’ll have to wait until Monday to clear up this mess.’

I took the weekend off, and spent it alone. I didn’t need a car to traverse the plain between Mount Fløyen and Mount Ulriken. I managed a run in Isdal valley as well. Both of these put me in a better frame of mind.

I searched for an Atle Helset on the Net, without finding much more than his address in Nordfjordeid. His name was entered as the CEO of A/S Helset Transport, but that was all I discovered. It was impossible to find out what his relationship to the Helset in the boundary dispute was. If necessary, I could make a few telephone calls.

On Monday morning, skimming through the newspaper I had delivered to my door every day, I spotted the headline ‘YOUNG MAN MISSING’, and that gave me something quite different to think about. The young man with the aquiline nose was easily recognisable in the picture. His name was Jonas Kleiva and he was twenty years old. He had last been seen during a 13demonstration against a salmon-breeding farm near Solvik in Masfjorden municipality on the previous Tuesday. The newspaper said he had been driving a brown-and-beige VW T3 camper van with a Vestland number plate. He was a student at the University of Bergen, and lived in the city, but he hadn’t returned to his bedsit in Sandviken after the trip to Masfjorden. Any information regarding his disappearance was to be passed on to Bergen police station or the closest police authority.

I rang the police and told them I might have some information about the case. The person I spoke to asked if I might be able to pop into the station.

‘So long as I can pop out again,’ I muttered under my breath.

The man at the other end said: ‘Sorry, I didn’t catch that.’

‘That’s fine. I’ll be right over.’

Once there, I was taken up to the third floor to see Inspector Signe Moland, who was handling the case. I hadn’t met her before. She was in her thirties and had blonde hair cut to a practical length. She was wearing a blue blouse, grey trousers and a light-grey suit jacket.

She received me with a professional smile and invited me into her office, which looked out onto the backyard.

Her surname interested me. ‘Are you by any chance related to Atle Moland?’

She nodded. ‘Did you know him? He was my paternal grandfather.’

‘Then I believe we might actually be related.’

‘Oh, yes?’ She looked at me with curiosity.

‘Your grandfather was my mother’s cousin. I must be second cousin to your father, although I don’t recall us ever meeting.’

‘Harald Moland. He was in the police as well. I’m the fourth generation, in fact. But most of the time he was in PST, the security service.’

‘In which case, I hope I went under his radar.’ 14

‘Well, I can’t remember him ever mentioning you. Veum, wasn’t it?’

‘Yes. Varg even.’

‘Hm.’ She smiled politely at that. ‘Well, let’s put the family to one side for a moment. You rang in to say you had some information about the disappearance of Jonas Kleiva?’

‘Yes. That is to say, I had no idea what his name was until I saw it in the press. And I don’t exactly have any information, either. What I have is a sighting. I think that’s the right term to use.’

‘A sighting could be of assistance to us.’

Without touching on any of the unfortunate circumstances in Sogn og Fjordane, I told her that I had caught the bus from Førde to Bergen the previous Tuesday and that I’d seen a man I was sure answered to Jonas Kleiva’s description, because of his appearance and the camper van he was standing next to. I told her about the two young women who had met him and described them as best I could.

She listened attentively to what I had to say and made a few notes on the keyboard in front of her, then checked the results on the screen.

‘Interesting. Is that all you have?’

‘Yes. The bus drove off while they were still standing there talking. My understanding from the newspaper article was that they’d been on their way to a demonstration against fish farming?’

‘Yes, near Skuggefjorden. A place called Solvik. There was a board meeting planned at the fish farm they were protesting against. Apparently, it was a spontaneous demonstration – no advance warning. From what we’ve gathered there were just a handful of protesters, and I assume these three were among them. You said the two women were carrying rolls of canvas. They were almost certainly banners for the demonstration. Young Kleiva has family in Solvik, by the way.’ 15

‘Close family?’

‘Mother. His parents are divorced. Father lives in Bergen, but from what we know, he has little contact with the son.’

‘You’ve spoken to the mother, of course?’

She nodded condescendingly. ‘He’d been to see her after the demonstration. That was the first she’d heard about it. Just a brief visit, she said, along with a girlfriend. Then he was going back to Bergen.’

‘A girlfriend? Probably one of the two I saw him with then. Did you get any names?’

She raised her eyebrows with a hint of irony. ‘No, we did not. But now that you’ve given us a hand, we might be able to find out who it could’ve been.’

‘So who reported him missing?’

‘That was his landlady in Bergen. He’d arranged to help her with a DIY job in the house the following day, so when he didn’t return from Solvik, she started to get concerned. She’d even spoken to Jonas’s mother on the phone, but it was actually the landlady who contacted us about him having gone missing. We waited for a few days. The mother told us about this girlfriend, so … well, we thought it wasn’t exactly unlikely that they’d go off somewhere together. But she wouldn’t give up, this landlady, so after conferring with the mother and the landlady again we decided to launch a search.’

‘And has it produced any results?’

‘Not so far.’

‘But these girls … ’

‘Yes, actually your information’s been very useful. Especially the fact that there were two of them. We’ll try to find out who they are and take it from there.’

The conversation had come to a halt. She leaned forward and shuffled a few documents that were lying in front of her. ‘Was there anything else you had on your mind?’ 16

‘No, not for the moment.’

She looked at me with arched eyebrows. ‘Later perhaps?’

‘I hope not. But, you know, in my line of business … ’

‘Which is…?’

‘I sort of thought I had my own section on the information board here. “Beware of the Wolf”, it might’ve said.’

‘Really? I’m afraid it doesn’t.’

‘No horror stories over coffee in the canteen?’

‘Now you’re piquing my curiosity.’

I gestured with my hands and angled my head. ‘Private investigator. No history with the force though, as more and more of my competitors seem to have.’

‘OK. Now the mists are clearing. In fact, your name has been mentioned a few times, if only en passant.’ She shuffled her documents again. ‘So, thank you very much, Veum. It was good of you to drop by with the information.’

I nodded and made a move to leave. ‘You can call me Varg. Perhaps we’ll see each other at a family reunion one day?’

‘Has there ever been any? I don’t recall hearing of one.’

‘Nor me. Perhaps they’ve crossed us both off the invitation list.’

She smiled wryly in a way that I vaguely seemed to recognise from her grandfather.

On the way out I nodded to Atle Helleve, who was sitting in his office with the door open, embroiled in a telephone conversation. After Hamre left the force, Atle had taken over as section head. He nodded back, without any visible enthusiasm, but then in these circles my appearance didn’t seem to excite any kind of welcome. Helleve was usually one of the more congenial officers, so perhaps his conversation wasn’t the most uplifting.

I walked back to my office to mope a bit more about the loss of my driving licence, which was currently in quite a different place – either Førde or Florø. It wasn’t with me anyway.

4

I received my driving licence through the post after approximately two weeks. The postal service was to blame for the long delay. In the meantime, I’d been in a position to print out a temporary licence from my own computer. This was all down to Vidar Waagenes, who’d done his job quickly and efficiently, persuading the police lawyer in Floro to drop the case, however reluctantly. I did have to go back to Førde to pick up my car though, which meant another bus trip to our northern neighbour.

The Corolla was neatly parked beside the chief of police’s office, in the same place Joralf Smalabeit had left it. They hadn’t confiscated the key, so I didn’t have to exchange any pleasantries with the police. I got behind the wheel, started the engine and headed back to Bergen without extending my stay in Førde any longer than necessary. I was meticulous about keeping to the speed limit all the way to the ferry terminal in Lavik, slowing down where the terrain and bends demanded, of course. When I reached the top of the climb up from Instefjord and came to the crossing where the two girls had got off the bus, I took a decision. I pulled in and checked my map before deciding on a little detour down to Solvik, out of sheer curiosity more than anything else.

Skuggefjorden, the shadow fjord, was well named. The tall mountainsides cast long shadows over the fjord, making the sea, which lay there rippling in the breeze, resemble unevenly laid tarmac, which was normal for this county. From the road I could make out some buildings around a bay screened by a headland in the south of the fjord. The B-road down from the mountain had been narrow enough, and it didn’t get any wider as I turned off and twisted and turned down the last few kilometres to Solvik. If you had to characterise the surroundings, ‘sparsely 18populated’ would be the right words. On my descent I espied a few unoccupied buildings – ghosts of abandoned farms. Only one of them – where a flock of goats was grazing on what was left of the grass – was bordered by a fence. I didn’t see anyone on the farm.

It was only when I reached the bottom of the hill that I saw any signs of life. Solvik became more built up the closer I came to the old quay, to the extent that the approximately twenty constructions could be called built up. There were cars parked in front of most of them. By the gate to one of the houses was a sign saying ROOMS FOR RENT. Down by the quay there were three holiday cabins beside a white house with green-stained cladding, where another sign said: CAMPING & FISHING LICENCES. Above the entrance I read SOLVIK STORE & CAFÉ in large letters. A red sign with a post horn and crown hung beside the door to announce that it was also a POST OFFICE. The signs suggested I had come to the indisputable centre of Solvik.

I parked and got out of the car. Now I could see that a newish road went south from the quay to an area further out on the headland. Large, open salmon pens floated in the fjord, as though a gang of boys had thrown extra-large frisbees out there.

Along one side of a house I saw a white Ford Transit van with SOLVIK TRANSPORT written on the top panel. In front of one of the holiday cabins was a grey 1980 Opel Ascona.

I went up to the white house and peered through the glass pane in the door, but couldn’t see any activity. Stuck to the window was a typed note: Mon-Fri 9–18, Sat 9–16, Sun closed. When I opened the door, a bell rang above my head. From a back room I heard a chair scrape as it was pushed backward.

The store had a limited selection of goods. At first sight it appeared to be catering for campers rather than local people. In a cooler with glass doors I saw mineral water, pop and cans of Coke. But a cooler in the opposite corner contained milk of all 19varieties, pots of cream and yoghurt, cartons of juice and a selection of canned beers, with and without alcohol. On the shelves they had mostly tinned food and dry goods. There was a choice of two types of bread, both wrapped in paper advertising a bakery in Hosteland. To the left of the entrance there was a small freezer with various kinds of ice cream, anything from ice lollies to desserts, and a modest number of frozen items. In front of one window, facing the street, was the part that constituted the café: two small tables and four chairs.

In the doorway behind the cash desk appeared a man I assumed was the owner. He seemed to have adopted a crouched posture, as though ready to defend himself against an assault. I guessed he was in his forties: dark hair, but flecked with grey. He was thinning on top, with a few tufts standing in the air – perhaps he had just come in out of the wind. He had a stocky figure, wore dark-blue jeans, a blue shirt that didn’t look quite fresh and an open, well-worn leather waistcoat. On his belt he carried a sheath knife. He eyed me suspiciously, as if a customer at this time of day on the first of October was an unusual phenomenon.

‘Hello,’ I said. ‘My name’s Veum. Do you run this place?’

That didn’t seem to allay his suspicion. ‘I do, yes. Stein Solvik. What do you want?’

‘Actually, I’m only passing through.’ I could hear how unconvincing that sounded.

It did to him, too. ‘Uhuh? Where to?’ As I didn’t answer at once, he continued: ‘I s’pose you’re going to Sunfjord Salmon, like most people we don’t know.’

‘Sunfjord?’

‘Yes, it sounds completely crazy to those of us who live here. I imagine they’re trying to appeal to the international market, using a name that sounds familiar, so it’s Sunfjord, with just one n. The English sun, then fjord.’ 20

I nodded towards the fjord. ‘Is that the farm on the headland you’re referring to?’

‘It is.’

He looked at me, waiting for a response.

‘Wasn’t there some kind of demo there a couple of weeks ago?’

‘A demonstration? I suppose you could call it that. There were a few young people who bowled up here and then left. No one was bothered. They didn’t get as far as the company premises. No one does without permission.’

‘Not even you?’

‘What would I go there for?’

‘Well … ’ I looked around the store. ‘To deliver food, for example.’

‘Would be nice. They do their big shopping elsewhere, like so many of the folk in this area. This business won’t make me rich, I can tell you.’

‘Did you see any of the demonstrators?’

‘Did I see them? They came in their toxic cars and gathered in the car park here.’ He gesticulated to the door. ‘A couple of them came in and bought ice lollies, a few bottles of mineral water and some chocolate. That was all. Then they all went to the headland together. Afterwards they went home. I haven’t heard anyone say they miss them.’

‘Well, that’s the point. Have you heard that one of them is actually missed? Or missing?’

He sent me a sharp look. ‘No, I haven’t … Missing? Who?’

‘His name’s Jonas Kleiva.’

He nodded, deep in thought, and repeated the name. ‘Jonas?’

‘Apparently he’s from this area, or so I’ve been told.’

‘Yeah … The Kleivas have been around here for generations. I know very well who Jonas is. His mother lives here.’

‘Yes, that’s what I was told.’

‘Her name’s Betty.’ A glint of something indeterminate appeared in his eyes, a mixture of cunning and schadenfreude. 21

‘Betty?’

‘Yes, her real name’s Elisabeth, but everyone calls her Betty. Even she does. She’s the one with rooms for rent, if you saw the sign, but I’d better warn you if you were thinking of renting one: they say Betty eats men for breakfast. Widow twice over. The third escaped by getting divorced.’

‘Sounds dramatic. It was Jonas’s father who survived then, I take it?’

‘Yeah, but his successor wasn’t so lucky. He died while hiking two years ago. He fell down the side of a mountain and was found by two guys out looking for him.’

‘And the first husband?’

His eyes narrowed as he focused on me. ‘That was more mysterious, if I can put it like that. They found him dead in bed one morning. Heart attack, it was said at the time, but folk here are saying something else now. She’s handy with herbs and the like, Betty is. That’s what folk say.’

‘But if there was anything suspicious about the death, surely it would’ve been investigated?’

‘Investigated? Don’t think so. Didn’t strike anyone as fishy, and we would know, coming from an area that has survived for generations by catching fish. And long before the fish farms came here too.’

‘Jonas lives in Bergen, I gather.’

‘Yes, I suppose he does now. He doesn’t come home often, at any rate, and it’s news to me that he took part in the demonstration, I have to admit.’

I waited a moment to see if he would continue. When he didn’t I said, ‘Actually, it was the café sign that drew me in here. What have you got on the menu?’

He looked at me almost open-mouthed. ‘We’ve always got coffee on the go and if you’re peckish, I can bung a few rolls in the microwave. I’ve got cheese and sausages too. Take the weight off your feet in the meantime.’ He pointed to the two tables by the window and disappeared into the back room. 22

I sat down and looked out. A lean, slightly stooped man wearing a black bobble hat, worn padded overalls, dark blue with reflector strips on the sleeves and chest, was coming from the quay. On his back he had a blue rucksack emblazoned with DNT, the Norwegian trekking association. When he arrived at the forecourt, he turned to the café and squinted at the window where I was sitting, as though wondering who I was.

The bell above the door rang as he stepped inside. He glanced in my direction and nodded in a measured way – it was someone he didn’t know. His face was sinewy and narrow, his eyes a piercing light blue. He had a couple of days’ stubble on his chin, streaked with grey, and an upper lip that revealed that he had snus underneath. From under his hat protruded some long, grey-brown wisps of hair that he had gathered like a little rat’s tail on the nape of his neck.

I nodded back without saying anything.

Stein Solvik appeared from the back room. ‘Hi, Edvard. Would you like a cup of coffee as well? We have townsfolk here on a visit.’

‘Thank you very much,’ the new arrival said. ‘And a roll too, if you have one.’

‘On its way. I’ll throw in a couple more, so … ’ Solvik nodded in my direction and disappeared into the back room again.

‘A Bergensian, I can hear,’ I said.

The man nodded, pulled out a chair and sat down at the same table as me. ‘Edvard Aga,’ he said by way of introduction and looked at me.

‘Varg Veum.’

He nodded, without seeming particularly interested.

‘I was just curious to see what it was like down by the fjord. I’ve never been here before.’

‘No?’ He gestured towards the window. ‘I have a cabin here. And for the last few years, I’ve been a resident.’

‘I see. What’s the attraction?’ 23

He cast a pensive eye over me. ‘The quiet. The silence. The absence of other people.’

‘“A place where no one would believe people could live”, like the eponymous TV series?’

‘That sort of thing.’

Stein Solvik reappeared, this time with a Thermos of freshly brewed coffee, a tray with two cups and a plate of four rolls cut into two. Half of them had cheese on, the others oval pieces of dark, reddish-brown salami. ‘Edvard’s my best customer. If it wasn’t for him I’d have had to close the shop.’

‘Come on now, don’t exaggerate,’ Aga said with a little smile.

‘He lives off the fish he catches in the sea, the potatoes he grows on his land and the bread he bakes himself, but he buys the flour here, and if he needs anything else, he comes to me for it.’

Aga pulled a face. ‘Well, I have to go further and further out into the sea to fish. Those bastards out there … ’ He motioned to the headland where the salmon pens were. ‘They’ve as good as emptied the bloody fjord.’ He turned to face me. ‘And it isn’t just the wild salmon that have suffered. You should see the cod and the pollock I fish from the sea. They’re so emaciated and ill that even my cat won’t eat them.’

‘And that’s because…?’

‘I’ll tell you: the bastards breeding the fish have spread so much sea lice and poison in the fjord that I wouldn’t even bloody swim in it. They should be taken to court. They’ve killed the whole sodding fjord. Once upon a time it was a jewel.’

He looked up at Stein Solvik, who nodded. ‘You are so right, Edvard. A jewel is the right word. That’s in the days when tourists used to come here.’ Now he looked at me as well. ‘Fishing for salmon. And not just Norwegians. The English and Germans, too.’

Edvard Aga gazed over at the window. ‘Is that your car parked there?’

‘The grey Toyota, yes.’ 24

‘If you have time to drive along the fjord, I can show you the source of all the misery.’

I hummed and hawed. ‘I have to be back in Bergen tonight, but … How far down?’

‘We can drive there in about fifteen to twenty minutes. And it’s worth the trip if you’re interested in haunted houses.’

I glanced at Stein Solvik. He was watching us with clenched lips and scepticism in his eyes, but didn’t say anything.

‘Well, if you say so, then OK. But surely we should … ’ I gestured to the food on the table.

‘Yeah, yeah, eat first, ha ha. Isn’t that the Sunnfjord motto?’

After we had finished off the rolls, drunk the coffee and chatted about what Aga had done before he moved here – teaching and selling properties – and how I made a living, we thanked the owner, left and got in my car.

Aga pointed. ‘Over there to the right, and then it’s a straight road the whole way.’

I nodded, started the car, turned round by the next house down towards the quay, passed a few more buildings and then we were out of the compact village of Solvik. The road narrowed and was soon a standard Vestland lane: one carriageway and passing places at regular intervals.

Aga chuckled beside me. ‘Private investigator, ha ha. First one I’ve ever met, I reckon. But to quote Elvis: “If you’re looking for trouble, you came to the right place.”’

I cast a quick glance at him. ‘Oh, yeah?’

‘Solvik village is divided into two parts, and those living on either side of the line barely talk to each other.’

‘Uhuh?’

I had to keep my eyes on the road, but he continued talking unprompted:

‘You saw the sparse selection of goods in Stein Solvik’s grocery store. He’s tried to stay neutral in the dispute, with the 25result that many people have boycotted him, regardless of which side of the fight they are on.’

‘So what are they arguing about?’

‘It’s been like the Middle East here over the past few years, and there are no signs of peace coming soon. It became even more dramatic when Klaus Krog died two years ago, while hiking.’

‘Stein Solvik mentioned him. He was married to Betty Kleiva, is that right?’

‘Not sure if they were married. I think they lived together. And there were ten years between them.’

‘OK. But what did his death have to do with the local dispute?’

‘You’re right to be confused. The whole reason for this witch’s brew lies there.’ He jabbed a finger at the fjord. ‘And what they’ve done to it. But when someone began to shed some light on the matter, things … ended as they did.’

‘By which you mean?’

‘The accident in the mountains, if it was one. Many have their doubts.’

‘But it was investigated?’

‘They call it so many things. A local policeman came here and walked the route they assumed Krog had taken, up to the summer farms in Fossedalen. He came back down and said it was perilously steep. Then he drove back to Duesund, or wherever it was he came from. After a while the police ruled that it was a case of misadventure and no further investigations would be undertaken.’

‘And that was accepted by … everyone?’

‘Absolutely not. I believe Betty contacted a lawyer, but never got any further, and I suppose the case is stuck there.’

‘When did this happen, did you say?’

‘Two years ago, in September 2002.’ 26

We were round a headland now. From here we could see the end of the fjord. A white waterfall plummeted down the mountainside from high above. On a piece of land in the foreground I glimpsed some dirty, grey buildings and a pier jutting into the sea.

‘There – you can see it,’ Aga said. ‘Markatangen. That’s where we’re going.’

‘OK. But this dispute you were mentioning – what’s it actually about?’

‘To put it simply, as far as that’s possible: breeding salmon and money. Should a salmon farm be in the fjord or on land? What’s best for the fish? What’s best for the fjord? What’s best for the environment?’

‘I don’t know a great deal about this, but I’ve followed the discussion. On land, I assume, in answer to all three questions.’

‘Precisely. And that’s where the conflict lies. Between – if this were a gangster war – the Marken gang and the Sørnes gang. And to put it in a nutshell, again, those from Marken were in favour of the land solution because they had experienced for themselves how destructive their own fish farm had been for the fjord. The Sørnes gang, however, who now have big, international capital behind them, back offshore cultivation and have established Sunfjord Salmon on the Sørneset headland.’

We were approaching our destination of Markatangen. The road led to a big gate surrounded by tall wire fences on both sides. But the gate was wide open and there were visible holes in the fencing, so there was nothing to stop us driving straight onto the forecourt. I swung up in front of the closest building and parked.

Aga had been right. It was like arriving in a ghost town. Three buildings with dark façades faced the car park. Several window panes were smashed. A sign above the door announced that MARKEN SALMON FARMS resided here, but the paint was 27faded and the primer coat grey. Nothing tempted you to go in to see if there was a ghost sitting in reception.

Aga stopped and looked down. ‘Actually, someone’s been here recently,’ he said, pointing to the tyre marks visible in the gravel. We raised our eyes and followed the tracks. They led straight to the pier.

Aga headed off in that direction. To the right of the pier were the remains of the old salmon pens, like abandoned UFOs in the fjord. ‘This is where the salmon were jumping when they started up in the 1980s. Now they’re not only dead in the pens but also in the whole bloody fjord. First came the salmon lice. Then they used poison to kill the lice. And we can see the consequences of both now.’ With a broad sweep of his arm, he indicated the fjord. ‘A dead fjord. Dead as a dodo.’

We had reached the end of the pier. The tyre tracks we had seen didn’t stop here; from what I could see they extended into the sea.

We stood staring down into the dark water for a moment.

Then Aga shouted, ‘Jesus Christ!’ and stared at me in alarm.

I nodded slowly, as if agreeing with him.

Beneath the surface we could make out an almost indefinable, light-coloured, rectangular form.

It was the roof of a vehicle. And if I wasn’t much mistaken, it was the same VW camper van I had observed up on the E39 just two weeks before.