7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Varg Veum

- Sprache: Englisch

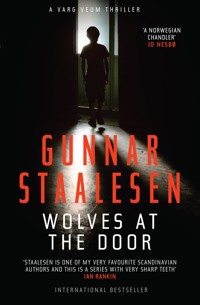

The wolves are no longer in the dark … they are at his door. And they want vengeance … The next instalment in the international, bestselling Varg Veum series by one of the fathers of Nordic Noir … 'One of the finest Nordic novelists - in the tradition of Henning Menkell' Barry Forshaw, Independent 'Masterful pacing' Publishers Weekly 'Mature and captivating' Herald Scotland 'The Norwegian Chandler' Jo Nesbø _________________ One dark January night a car drives at high speed towards PI Varg Veum, and comes very close to killing him. Veum is certain this is no accident, following so soon after the deaths of two jailed men who were convicted for their participation in a case of child pornography and sexual assault … crimes that Veum himself once stood wrongly accused of committing. While the guilty men were apparently killed accidentally, Varg suspects that there is something more sinister at play … and that he's on the death list of someone still at large. Fearing for his life, Veum begins to investigate the old case, interviewing the victims of abuse and delving deeper into the brutal crimes, with shocking results. The wolves are no longer in the dark … they are at his door. _________________ Praise for Gunnar Staalesen 'Gunnar Staalesen is one of my very favourite Scandinavian authors. Operating out of Bergen in Norway, his private eye, Varg Veum, is a complex but engaging anti-hero. Varg means "wolf " in Norwegian, and this is a series with very sharp teeth' Ian Rankin 'Almost forty years into the Varg Veum odyssey, Staalesen is at the height of his storytelling powers' Crime Fiction Lover 'Staalesen continually reminds us he is one of the finest of Nordic novelists' Financial Times 'Chilling and perilous results — all told in a pleasingly dry style' Sunday Times 'Staalesen does a masterful job of exposing the worst of Norwegian society in this highly disturbing entry' Publishers Weekly 'The Varg Veum series is more concerned with character and motivation than spectacle, and it's in the quieter scenes that the real drama lies' Herald Scotland 'Every inch the equal of his Nordic confreres Henning Mankell and Jo Nesbo' Independent 'Not many books hook you in the first chapter – this one did, and never let go!' Mari Hannah 'With an expositional style that is all but invisible, Staalesen masterfully compels us from the first pages … If you're a fan of Varg Veum, this is not to be missed, and if you're new to the series, this is one of the best ones. You're encouraged to jump right in, even if the Norwegian names can be a bit confusing to follow' Crime Fiction Lover 'With short, smart, darkly punchy chapters Wolves at the Door is a provocative and gripping read' LoveReading 'Haunting, dark and totally noir, a great read' New Books Magazine

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 414

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

iii

vii

Wolves at the Door

GUNNAR STAALESEN

Translated by Don Bartlett

ix

‘For without are dogs, and sorcerers, and whoremongers, and murderers, and idolaters, and whosoever loveth and maketh a lie.’

(Revelations 22:15)x

Contents

1

I heard the car before I saw it.

I had been on a little job for a married couple who lived in one of the new residential areas at the rear of Lagunen Shopping Centre. They had asked me to park discreetly when I visited them, and I was on my way back down to my Toyota when I heard a snarling engine just behind me.

I had enough time to turn around. The vehicle was coming straight at me with no indication that it was going to veer away. For a second or two I was paralysed. Then I reacted instinctively and hurled myself to the side. The car was so close to me that I felt a rush of air as it passed.

I fell into a pile of snow the JCB ploughs had left during the Yuletide break. Now it was the first Sunday in January and the weather was as cold as it had been since Christmas.

What the…? I said to myself.

My heart pounding, more shocked than frightened, I sat up in the snow and stared at the tail lights of the car racing down at the same breakneck speed. It was much too far away for me to read the registration plate, but in the evening gloom the car looked grey, and if I wasn’t much mistaken it was last year’s model of the VW Golf. I watched the tail lights go past the shopping centre and out to Fanavegen, where it took a right into Bergen and disappeared behind the hills there.

I struggled to my feet and stepped onto the road. I looked up to make sure there were no more cars hurtling down at me and to see whether anyone was out walking who could confirm what had happened. But there was no one in the area between Lagunen and the petrol station before Fanavegen.

Hadn’t the driver seen me or had he seen me all too well; in other words, had he intentionally tried to mow me down? Could it have 2anything to do with the case I had just solved? Hardly. It was so insignificant that the only people who might react to it would be the tax authorities, because my fee was so modest that there was virtually nothing left for them, even including VAT.

On the way to my Corolla it struck me there might be another link and this worried me. I became even more worried than I had been when I first noticed the two deaths: one in October, the other two months later.

I had made only a mental note of the first. After the second, I had a suspicion there was something fishy going on. In both obituaries the surviving families had used the words ‘died suddenly and unexpectedly’ and this is what set me thinking. ‘Suddenly and unexpectedly’ as in … murdered?

But there had been no mention of it in the newspapers I had seen. I hadn’t met either of the two men, but their names – Per Haugen and Mikael Midtbø – had been seared into my memory.

Soon it would be a year and a half since we had, for a few dramatic autumn months, shared a similar fate: all three of us had been accused of the same crime. This was a period of my life I had consciously tried to repress. Now it all came flooding back.

When I reached my car, I unlocked the door, got behind the wheel and rewound the previous sixteen months, to the morning when I was woken by the police for what in the course of a few days would develop into the worst nightmare I had ever experienced, and I had been wide awake.

2

It had been an experience I would not have wished on my worst enemy.

I was taken to the police station and charged with being in possession of what they now called ‘sexually explicit material’ on my computers: films, pictures and books featuring child abuse. And I wasn’t the only person to be charged. Three other men had been brought in for the same reason, and during a later interview I found out their names: Mikael Midtbø, Per Haugen and Karl Slåtthaug.

I knew of course that I was innocent and that someone had planted this material on my computers, but that convinced neither the police nor the legal system. After the initial hearing I was held in remand while the case was investigated further. During another interview at the police station I seized an opportunity to escape, and then the nightmare began in earnest. In a race against time I did what I could to get to the bottom of the case, in which the main issue was this: who hated me with such an intensity that they had hacked my computer and planted this material? I found the answer in a summer house in the village of Søre Øyane, Os Municipality, in a confrontation with four other individuals, all involved in the case in various ways.

However, one of them got away. Later that evening I was standing by a diving tower facing Bjørna fjord, searching in vain for a man who had slipped into the sea after being outed as one of the ringleaders in the case. Wave after wave of breakers crashed on the shore, the wind howled around my ears, but no one reappeared from the foaming waters. He had been swallowed up.

I managed to get off the slippery, sea-soaked rocks. Back on dry land I rang two people: first Sølvi, to say everything was in the process 4of resolving itself, then my lawyer, Vidar Waagenes, so he could help prevent those words from coming back to haunt me.

It hadn’t been so easy. When I returned to the summer house I was arrested by armed police, unceremoniously handcuffed, led to a vehicle and delivered post haste to Bergen Police Station. The only information I managed to pass on was that they should start a search for a man in Bjørna fjord. I didn’t find out until later whether that had been done. The orders from the operational commander, an officer I had never seen before, to the policemen taking me to the car had been short and sweet: This man has escaped remand before. Don’t let him out of your sight for a second.

They didn’t either, until they handed me over on the third floor of the police station, where the department head, Jakob E. Hamre, received me with a thick layer of repugnance daubed across his already-pale face. I made an attempt to clarify the situation for him, but he interrupted me with a raised hand: ‘I think we’ll wait until Waagenes is here, Veum, before we say anything.’

Fortunately, it wasn’t long before Waagenes arrived and I was able to start explaining. In addition to Hamre, Inspector Bjarne Solheim took part in the interview. He glared at me sourly, and I could well understand why. It was fairly clear that he had been blamed for allowing me to abscond a few days earlier.

The interview was recorded. Solheim sat writing on his laptop and both Hamre and Waagenes took notes. Initially, they let me talk more or less without interruption as I tried to summarise a case that had its roots in the past.

We talked until late in the night. After a few hours a report came back to Hamre to say that the search for a man in Bjørna fjord had been unsuccessful, but they would continue looking as soon as there was daylight. ‘The most important element of your proof is there,’ Hamre had commented, but Waagenes protested at once: ‘Not at all! Varg’s furnished you with so much information that as soon as you’ve examined all the other detainees’ computers and mobile phones there should be more than enough evidence for his statement.’

‘Let’s hope so. We’ll have to rely on the experts here.’5

‘You’ve arrested the other three, I take it?’ I asked, and Hamre nodded in a measured way.

‘They’re being interviewed, but we’re unlikely to get through all the material tonight. You’d better prepare yourself to stay here longer until we feel we have a clear overview.’

‘I object!’ Waagenes exclaimed. ‘You’ve both known Veum for many years…’

‘Indeed,’ Hamre mumbled with an eloquent sigh.

‘It’s utterly inconceivable that Varg would’ve downloaded sexually explicit material with his background as a child-welfare officer and a private investigator.’

‘Don’t forget the incriminating photos,’ Hamre said.

‘Which Varg has explained.’

‘Exactly. He has explained. Quod erat demonstrandum, as we Latinists like to say.’

‘Yes. And Mother Nille is a rock – Ludvig Holberg told us all we need to know about Latinists,’ Waagenes commented drily.

But Hamre won the tug of war in the end. I was still formally charged and had to spend further days and nights on remand, interrupted only by more tedious interviews.

On the third day I was summoned to yet another interview, where the police lawyer Beate Bauge, Hamre and Waagenes were present. Bauge was as erect and disgruntled as she had been for all the hearings. The look she sent me before she started speaking told me her hand had been forced. However, the conclusion was clear. Preliminary examinations of the other detainees’ computers had led to them taking the following decision: the charge against me had been withdrawn. After a short, dramatic pause she added: ‘For the time being.’ And she stressed that if any evidence to the contrary appeared I would have to expect to be brought in for further questioning.

It was as if snow was falling quietly inside me. I didn’t erupt in whoops of joy and I didn’t burst into tears. However, I did feel a huge amount of relief that they had at long last taken me at my word and that the other computers had corroborated what I had told them.6

‘And the other arrestees?’ I asked warily.

‘They’ll stay on remand until they’re indicted.’

‘And Sigurd Svensbø? Has he been found?’

Bauge looked at Hamre, who shook his head.

‘No. But our experience of missing persons at sea is that it can be a very long time before bodies wash ashore, if ever.’

‘If ifs and ands were pots and pans there’d be no need for tinkers,’ Bauge said with the same disgruntled expression she wore earlier, and there were no further comments.

I left the police station in the company of Vidar Waagenes. On the doorstep outside we exchanged glances. It was as though I still hadn’t realised I was free, that I could do whatever I wanted – whether that was to go home, down to my office, visit Sølvi or catch the next plane to wherever in the world. In the end, Waagenes and I went for an early lunch at Holbergstuen, as of old.

But that was almost a year and a half ago. Now something had happened that had brought the case back to life. The first thing I did when I got into my office on Monday morning was ring Hamre, albeit with extreme reluctance.

3

Since the events of that autumn I’d worked on one big case, and an incidental consequence of it still lay in the bottom drawer of my desk, in an unopened envelope postmarked the Public Health Institute. I had sat weighing this in my hand many times without taking the decision to open it. In it I imagined was the result of the tests I had requested the DNA registry office perform: I’d sent a few strands of long-deceased saxophonist Leif Pedersen’s hair and one of mine. If the tests proved to be positive, I had a new father. If not, I would have to assume that the likewise deceased tram conductor, Anders Veum, was still my biological father. For some reason I had a strong aversion to opening the letter. After all, I had grown up with the tram conductor. He was my father figure, inasmuch as I had one. The saxophonist had come out of left field, holding his instrument, for which I had a special affection, although I never knew why.

Besides, I had quite a different problem now. Hamre hadn’t exactly been delighted to hear from me. And his mood didn’t improve when I told him why I wanted to talk to him and what the case was about. But he cleared the decks for a meeting in his office half an hour later. ‘Half an hour? That’s quick.’ ‘That’s when I have some time, Veum.’ ‘The sooner, the better,’ I answered, and twenty minutes later I was on my way.

There were still remnants of the snow that fell before Christmas on the edge of the pavements. The mountainsides around the town were a painting in black and white. I had celebrated Christmas Eve with Sølvi and Helene at their place in Saudalskleivane. On New Year’s Eve Sølvi had invited some friends round. I had been as discreet as possible and remained in the background, but raised my glass of champagne at 8midnight with the other guests. The turn of the year had never been high on the list of occasions I wanted to celebrate. I had spent most of them in solitary majesty, except for my loyal companions – a bottle of aquavit and the rain.

I only moved back to Telthussmuget when the New Year weekend, and what had reminded me of a good old-fashioned Christmas holiday, was over. It was definitely over when on a Sunday in January I just managed to avoid being mown down by a car that had undoubtedly had me in its sights. Even now, walking to the police station the day after, I looked twice both ways when I crossed the road, Torgallmenningen first, then Domkirkegaten.

Hamre sent Solheim down to reception to collect me. He still didn’t appear to have forgiven me. I noticed that he had assumed a new style. His once very untidy hair was shaven down to a classical crew cut, like a subordinate officer in the sixties, when I myself was doing my national service. As he was hardly likely to have planned a military career, I took this as a clear sign that he envisaged himself climbing up the hierarchy of Bergen Police Station, where the length of your hair was perhaps still a factor.

Hamre, on the other hand, was the same as always, only even paler, like an overexposed photograph in which the white dominated. The sole feature to break this sameness was the grey of his tailored suit. There had always been a classical elegance about Hamre, whom I had known in our usual ping-pong way since the late seventies. Basic arithmetic told me that he must have been getting on for pensionable age in the police, which the tired expression on his face reinforced.

He received me with a kind of resignation, pointing to the free chair on the visitor’s side of his desk. ‘Take a seat. Can we offer you anything? A cup of coffee? The force’s finest, lukewarm since seven o’clock this morning.’

‘No, thank you. I sleep badly enough as it is.’

‘Now, don’t say I didn’t offer you a cup, Veum.’

Solheim sat down on the third chair in the room, at the side of the desk, on which he placed his laptop. He raised his gaze and looked at me, as laconic as a court reporter at the start of a long hearing.9

‘What did you say on the phone? You want to report someone? What for?’

‘Someone tried to run me over last night, behind Lagunen.’

‘Oh, yes? Can you give us any details?’

I told him the little I knew. It wasn’t much.

He motioned to Solheim to take notes, which he did with poorly concealed irony. ‘A VW Golf, probably grey, last year’s model, no registration number. Did you catch all of that, Bjarne?’

Solheim nodded.

‘Any suspicions about who it could’ve been?’

‘Not yet.’

He turned the words over in his mind. ‘Not yet. Hmmm. But it was my understanding that you were worried about the deaths of two of your co-accused in the big child porn case in 2002.’

‘The charges against me were dropped.’

‘Yes, of course. We remember. Under a cloud of doubt. The star witness from Bjørna fjord still hasn’t appeared, as far as I’ve been able to establish.’

‘No, but … Do we want to go through all of this again?’

‘No, no, no,’ he said, quickly. ‘That was just an icebreaker, to get us in the right mood. How long have we known each other, Veum?’

‘I was thinking the same myself. Our paths first crossed during a case in 1978. So, in my head that makes it about a quarter of a century ago.’

‘In mine, too. Twenty-six years ago to be absolutely accurate. And do you know what?’

‘It feels as though it were yesterday?’

He pointed to a calendar of the neutral variety on the wall. ‘Can you see the red circle around the thirtieth of January?’

I followed the direction indicated by his index finger. ‘Yes.’

‘That’s a Friday by the way. And it’ll be my last day in the police force.’

‘I had an idea something like that was coming.’

‘And let me put it this way, as civilly as possible. The less I see of you this month, the better. In the future, in ten to fifteen years, we can have 10a glass of beer together in a suitable watering hole and chat about the good old days, but right now … No, thank you. In this building your name’s synonymous with trouble, but of course you know that yourself. You just don’t care.’

Solheim was following our conversation with what looked suspiciously like an amused glint in his eyes. Hamre concluded his monologue. ‘So let’s get down to brass tacks and finish this as fast as we can. You wish to make an official complaint about an unknown person, or unknown persons, who, according to you, at ten o’clock last night tried to run you over, at such and such an address in Fana, the Bergen district in question.’

‘Yes.’

‘Did you catch that, Bjarne?’

Solheim elevated his fingers from the keyboard as a sign that this was already documented.

‘Then I promise we’ll look at this more closely. How many such cars do you think there are in the Bergen region, Bjarne?’

‘Mmm.’ He took his time. ‘Probably several hundred.’

‘If we collate a list of all the registered owners I’m sure we can email it to Veum to see if he recognises any of them, can’t we?’

‘I’ll do that. After all, we have his email address.’ He smirked.

‘Laurel and Hardy on a new adventure,’ I said. ‘You don’t seem to be taking this very seriously.’

Hamre sent me a stern look. ‘We take every single complaint we receive seriously. It’s only a lack of capacity that prevents us from clearing up all of them. And, of course, how much information we’re given.’ He raised his eyebrows sardonically, almost as a challenge to me to bat the ball back.

‘And what about the two deaths?’

‘Yes, tell us some more about them. I asked Bjarne to dig up what we have on both cases.’

‘In other words, you’ve opened files on them?’

‘We have, after the duty doctor’s report. A sudden death’s a sudden death. So … what can you tell us?’11

I took out my notepad and opened it. Both obituaries were there. I laid them down in front of Hamre on the desk so that he could examine them for himself, if he felt the need.

‘So, there are two deaths. One in October, the second in December. Both obituaries say the deaths were sudden and unexpected.’

‘One of the adjectives is redundant, if you ask me.’

‘Let’s take the more recent death first. The man’s name was Mikael Midtbø and he died on the third of December. According to the obituary, he left behind two persons, both women, but it isn’t clear from the text what their relationships to him were. One’s called Svanhild and the other Astrid.’

Solheim tapped on his laptop. ‘That’s correct. His partner and her daughter.’ After a glance towards Hamre he added: ‘A relatively new relationship. When we investigated the case in 2002 he still had an address in Frekhaug.’

I noted that on my pad. ‘And what do you know about the death itself?’

Hamre looked at Solheim. ‘Accidental death. A fall, wasn’t it?’

‘Yes. From the tenth storey of a housing block in Dag Hammarskjølds vei.’

There was a tiny pause before I spoke up again. ‘And you’re sure this was an accident?’

The two policemen exchanged glances. Hamre nodded to Solheim and let him answer. ‘We questioned some people, of course, and we carried out our own investigations. But, as I’m sure you know, if we’re talking suicide, we always keep mum with regard to communicating with the media and so on.’

‘And did you conclude it was?’

‘Yes, we did.’

‘And what did you base your conclusion on?’

‘We talked to his partner, some neighbours and an eyewitness.’

‘An eyewitness?’

‘Yes, indeed. A woman was passing below with a pram; Midtbø hit the ground only a few metres from her.’12

‘She saw the impact, in other words, but not the fall itself?’

‘Yes, and she was quite shocked, naturally enough.’

Hamre coughed. ‘His partner also expressed the view that Midtbø had been unstable in the time leading up to the fall.’

Solheim nodded. ‘Ever since the police action he’d been depressed and irritable. Like certain others…’ He snatched a quick glance at me. ‘He’d proclaimed his innocence. But there was evidence against him too, images, and he didn’t get any support from his then wife, who separated from him while he was on remand.’

‘I assume you checked the alibis of all those involved?’

Hamre sent me a condescending glare and nodded once more to Solheim. ‘Of course. This happened at approximately twelve o’clock. His partner was at work, which colleagues corroborated. Her daughter was at school. We even checked out his ex-wife, to be on the safe side.’

‘No one else who might’ve had a grudge against him?’

‘Loads probably, if we take a broader perspective, but … There was no evidence to suggest that he hadn’t decided to end his life, on an impulse maybe, bearing in mind the method and the time of day—’

Hamre interrupted. ‘If there are any sudden new developments, we can pick up where we left off. That’s where we are now. Nothing’s written in stone on this one.’

‘In which case it would be a gravestone,’ I muttered under my breath. Aloud, I said: ‘Something new has come up.’

‘Oh, yes?’

‘The attempt to run me over!’

‘Mm. Shall we look at the second case first?’ He gestured towards the two obituaries. ‘As far as that one’s concerned … Per Haugen was an elderly man, seventy-two years old. He was found dead on the Eidsvågsnes headland at Frøviken bay, where he used to go fishing in the morning almost every day. The autopsy report gave as the cause of death drowning in combination with a heart attack.’

‘No external signs of violence?’

‘None.’

‘So you didn’t launch an investigation?’13

‘We talked to his wife. It was her who told us about his fishing. Otherwise he never went out during the day.’

‘They were still married, I take it?’

Hamre nodded.

‘Children?’

Solheim tapped away. Without raising his eyes from the screen, he said: ‘Two grown-up children. A son and a daughter. Two grandchildren. Neither of the Haugens’ children had any contact with their parents. The daughter was a witness and told the court about how she’d been abused. But it was so long ago that the court couldn’t take that into account in their sentencing.’

‘She sacrificed herself for no purpose, in other words.’

‘You could put it like that.’

‘But both of them were imprisoned, Midtbø and Haugen? And then they were out again by the autumn?’

Hamre sent me a bitter look. ‘They weren’t given long sentences, and good parts of them were conditional. With regard to Haugen, age must’ve played a part. Both defence counsels referred to the withdrawal of the charges against you – or an earlier suspect, as they called you – as a form of precedence. That’s what’s often so desperate about these cases. The strict requirements for forensic evidence. Maybe someone had hacked into their computers, too? This kind of thing is meat and drink for a defence counsel of the right calibre, and here they definitely received a high degree of support from the court.’

‘Well, don’t blame me! I was innocent.’

‘We’ve accepted that. Our own computer experts convinced us. May I emphasise “our own”?’

‘Thank you.’

‘But back to the case. At best it’s our word against theirs. Images are damning primarily if they’re of the suspects’ own children – or of others in their circle of acquaintances – and they’re recognisable. If not…’ He leaned forwards. ‘We don’t have the resources to get to the bottom of these cases. But no one should feel safe. We’re improving. Technology’s improving, even in the police force. I’m afraid we can only see the tip 14of the iceberg here. If you ask me, there’s pure evil out there. In the whole of my police career nothing has shaken me more than meeting the guilty parties in cases such as this one, with children as young as infants victims of sexual abuse.’

‘I don’t think I’ve ever met pure evil, Hamre. If so, it must’ve been purely pathological.’

‘Well, I’m sure it’d be hard for a social worker like you to understand that such evil exists. But we – Bjarne and I, and many of our colleagues – see the victims of this, and for us there’s no other explanation.’

‘Absolutely. I share your revulsion and have myself met such victims, back in my social-welfare days, but … Well, there’s a third person on the list too. Karl Slåtthaug, the fourth man to be charged in 2002. Do you know anything about him? Surely he didn’t get off so lightly, did he?’

‘Oh, no? He was let off the hook too. Didn’t even have to report to the police station!’ Hamre’s face was flushed. ‘Bloody defence counsels! Sometimes you wonder what people are like inside.’

‘He’s left town, I hear,’ Solheim said.

‘Oh, yes?’ Hamre turned to his colleague.

‘Far?’ I asked.

‘Vestfold. Tønsberg, unless I’m much mistaken.’

‘And he’s alive?’

Solheim shrugged. ‘For all I know, yes.’

Hamre took over. ‘As you can see, Veum, we’re not complete idiots in the police. We have the usual suspects under surveillance, even if they move away from the district.’

‘Perhaps he should be given a warning, at least?’

‘A warning? That someone might crash their car into him? If only they had.’

We sat for a moment looking at each other. In the end, I said: ‘You don’t mean that.’

‘No? You warn him then. In many ways you’re closer to him.’

The atmosphere in the room was beginning to become oppressive. I made an attempt to change the focus. ‘Re: my own case. There were three men charged at first. But during the operation in Bjørna fjord 15three more were arrested. The professionals, if I can put it like that. Where are they?’

He looked at me sombrely. ‘They’re still on remand, but there are appeals in hand for all three of them, so don’t be surprised if you bump into one of them in the street during the next six months or so.’

‘Two of them were involved in murder.’

‘Which wasn’t that easy to prove so long afterwards. You probably have enemies out there, Veum. Maybe you should get used to taking a long, hard look before you cross the street for some time to come.’

‘At any rate, I cleared up the case. What if I hadn’t done the investigating myself?’

‘After absconding from remand. Thank you very much. You shouldn’t underestimate the likelihood that we would’ve come to the same result if we’d been allowed to do our job in peace. You are, and have always been, what Americans call “a pain in the ass”, Veum.’

‘They have ointment for that, Hamre.’

Solheim sat tight-lipped listening. I could see his brain overheating, but he said nothing. Not this time, either. The look he gave me was eloquent enough.

I spread my arms in conciliation. ‘Well … what if I find out there’s really a link between these two deaths, and neither of them died of natural causes…?’

Hamre smacked both hands down hard on his desk and rose halfway out of his chair. ‘Let me make one thing absolutely clear to you, Veum. You won’t find out anything. If I see you just once in my office before the thirtieth of January I’ll have you hauled before the bloody court again, even if it costs me half my pension!’

‘For that money you could just about buy a semi-decent midfielder for FC Brann.’

‘There are already two corpses here. We don’t want any more.’

‘Ah, you’re thinking about me after all, I can hear. You’re taking my complaint seriously, are you?’

Hamre looked at Solheim, desperate. ‘What shall we do with this character? Hang him up to dry and let the flies feed off him?’16

We eyed each other. We were both clearly in a droll frame of mind.

‘You can go now, Veum. I think we’ve finished talking.’

‘Can I expect to hear from you regarding my complaint?’

He waved an arm, resigned. ‘You’ll hear from us.’

I stood up and put on my winter coat. ‘Alea jacta est, as the late Julius once said.’

Hamre turned to Solheim. ‘Would you accompany him out?’

Solheim rose to his feet. ‘With pleasure.’

I raised a hand to Hamre. ‘Enjoy your retirement. A beer in ten to fifteen years, wasn’t that what you said? Deal.’

‘Let’s make it twenty,’ he said, smiling wryly and shooing me away.

Solheim accompanied me onto the pavement, without saying so much as a single word of any kind. However, there was one thing I was sure of. I might never meet Hamre again. But Solheim shouldn’t feel too safe. Our paths would cross for certain. That was a guarantee signed and sealed in blood.

4

The cloud cover was high and white, like a dull bell jar over the town. I stuffed my hands deep into my coat pockets as I strolled back to the office after the meeting with Hamre and Solheim.

Back at my post on the third floor I checked the answer machine and saw that no one had asked after me while I was away. Surprise, surprise. I put on the kettle in the hope of brewing a better coffee than I had been offered at the police station.

While I was waiting for the water to boil I took out my notepad, laid the two obituaries out in front of me on the desk and read the notes I had made during the conversation.

Both obituaries were very simple. Not only did they use the same language – ‘died suddenly and unexpectedly’ – but there were remarkably few surviving relatives. Under Mikael Midtbø’s name there were only two: Svanhild and Astrid. Followed by information about the funeral, which was to take place in Fyllingsdalen Church, and a final postscript: ‘Please don’t bring any flowers. The church ceremony will conclude proceedings.’ His ex-wife and children were conspicuous by their absence. Per Haugen’s obituary was equally laconic. In his, too, there were only two names: Tora and Hans. After Hans, ‘brother-in-law’ was written in brackets. There was nothing about flowers, but here too the funeral ceremony terminated in the church, in Biskopshavn.

It was clear that neither Mikael Midtbø nor Per Haugen was considered worthy of a commemorative speech, not even by their closest family, but I was not unaware that some people would have gladly danced on their graves. The absence of overt grief from the surviving family told its own story.

There was a marked age difference between the two deceased. 18Haugen was to some extent old enough for the police to have no problem declaring that he had died of natural causes. As for Midtbø, however … a fall from the tenth storey of a block of flats in Fyllingsdalen. Mm. I would have made further enquiries. But my days were filled with leisure; clients weren’t beating a path to my door. The job in Fana had been the only one in the last fortnight. The workload was probably greater in Domkirkegaten, at the police station.

The kettle was boiling. I took a filter, measured the required amount of coffee and poured the water. The aroma of freshly brewed coffee spread through the room like the perfume of an exotic woman, darkskinned, big smile. On looking more closely, however, I saw her back was bent from lifting far-too-heavy sacks on a plantation in Brazil for what was a pittance when compared with the sums at which her employer in Bergen and in other places was quoted on the stock market. So perhaps her smile wasn’t that big after all. But the coffee was good, no two ways about that.

I poured myself a cup, took it with me to the computer, booted up and began to search for two people by the names of Svanhild and Astrid in Dag Hammarskjølds vei, 5144 Fyllingsdalen. I couldn’t find an Astrid, but a Svanhild, surname Olsvik, appeared, with an address in what I thought was one of the high-rises by Fyllingsdalen Cemetery. She had a mobile phone and a landline. I jotted down both numbers.

While I was at it I searched for the surname Midtbø in Frekhaug. Only one name came up: Haldis Midtbø – she also had two telephone numbers. As I clearly had the wind behind me, I tried Haugen too. Per and Tora Haugen lived in Brunestykket, not far from Frøviken bay, where his body had been found. Here there was only a landline number. His brother-in-law, Hans, would have to wait, as I had only his Christian name.

Cup of coffee in hand, I stared out of the window. The snow lay like a bridal veil over Mount Rundemanen. Bryggen, on the other side of Vågen bay, was conspicuously deserted. The tourist season was months away and Bergensers had other things to do than go for a stroll. Most were probably doing what I was doing – staying indoors in heated 19offices, shops, or at home. Only the fittest were skiing in the nearest mountains.

I had several options to choose from. I could shut the office for the day, go home, fetch my skis from the cellar, carry them on my back and head for the hills as well. But I wouldn’t make much money if I did that.

Or I could ring one of the phone numbers I had jotted down and blindly pursue an investigation no one had asked me to set in motion. I wouldn’t earn much from this either, as I was my own employer. On the other hand, I had every reason to be on the alert. The failed bid to run me over the previous evening was still firmly in my mind. There could, for example, be a third way of engineering ‘a natural death’, even if a hit-and-run job would probably make the police sit up and take notice more than they had done in the Midtbø and Haugen cases.

I got to my feet, went over to the worktop and poured myself another coffee. When I sat down I opened the lowest drawer to the left and gave the bottle of aquavit a reassuring pat on the back. ‘Out of sight, but not out of mind,’ I said to it. But this wasn’t a day for aquavit. Not yet.

I rang Svanhild Olsvik’s home number. No answer.

I rang her mobile phone. She answered.

5

She didn’t sound very friendly.

I told her who I was and said I had been asked to investigate her late partner’s death.

She barked: ‘Who by?’

‘I can’t tell you.’

‘Hah! It’ll be that bitch, I bet.’

‘May I visit you at home?’

‘Absolutely not.’

‘Somewhere else then?’

‘I can’t see what the point is. It’s more than a month since it happened, and the police closed the case ages ago.’

‘Too early maybe?’

‘Too early! What do you mean by that?’

‘There are … a few loose ends. I can explain when we meet.’

‘If we meet.’

‘You must be interested in knowing what happened. Or…?’

‘Or what?’

I could have answered: Or perhaps you know already. But I didn’t. I said: ‘You must’ve asked yourself a few questions afterwards, surely? And your daughter? How did she react to the drama?’

‘You bloody keep my daughter right out of this!’

‘By all means. It’s you I want to talk to.’

‘OK then. But it’ll have to be somewhere with lots of people around. The café in the square inside Oasen. Could you be there in … half an hour?’

I did a quick mental calculation. ‘I can jump on a bus. Give me a bit more time in case I’m unlucky with the schedule.’21

‘Three quarters of an hour. Not a second more.’

‘And how…?’

But she had already hung up. I would have to hope I knew who she was when I got there.

In fact, catching a bus was the best option. I put my computer on standby, pulled out the plug of the kettle, slipped on my winter coat and rushed off. The services to Fyllingsdalen went through Olav Kyrres gate and I jumped on a bus at the last moment, so in fact I was able to alight by Oasen within the thirty minutes she had first suggested. I ran through the entrance by the office of the insurance company that had given me plenty of jobs, that was until a few years ago, when my contact moved to pastures new and the link was lost, which meant my financial status sank a few more notches.

A long corridor with a view into one of the supermarket chains in the mall led to the large square in the centre of the massive building. They had planted a few palm trees in large containers to give the impression that you were in the middle of the natural phenomenon the mall was named after. For me, the name Oasen had never appealed. Most of Fyllingsdalen was greener than the brick desert here. But then the shopping centre known as Lagunen was no sheltered idyll either. The choice of names for malls in the Bergen region owed more to a yearning for sunnier climes than what they were: overcrowded ant hills paying their dues to commercialism.

I stood at the entrance to the café that occupied a large part of the square and looked around, obviously searching for someone I knew – or didn’t know. I met the gaze of a robust, dark-haired woman sitting in the middle of the room and wearing black glasses and black clothes, from her jumper to her velvet trousers. She glared at me and I seemed to recognise the voice on the phone in her eyes.

I looked at her with raised eyebrows and she returned a belligerent glare. It had to be her. ‘Svanhild Olsvik?’

She nodded.

There was a free chair at her table. She had an empty cup of coffee in front of her. ‘I’ll go and get a coffee. Would you like a refill?’22

She shook her head. ‘I’ll be off soon.’

‘I won’t be a moment.’

I joined the queue at the counter, poured myself a coffee from the machine and ended up behind an elderly Bergensian lady at the cash till. She was so immersed in her account of her grandchild’s merits that I just elbowed in, threw the money on the counter and said to the listening head that she could keep whatever was left over, which she accepted absent-mindedly, sweeping the money into her apron pocket without even so much as a question as to whether I wanted a receipt.

I hurried back, coffee spilling into the saucer, sat down on the free chair and adopted my most charming expression. ‘I apologise for bothering you during your working day.’

She shrugged. ‘It’s over.’

‘What’s your job?’

‘Cleaning consultant,’ she answered with a defiant look, in case I should be so bold as to call her job anything else. ‘I can’t understand why I’m talking to you.’

‘I’ll be as brief as possible. Let’s get straight to the point. Your partner, Mikael Midtbø, died after falling from the tenth floor of the block where you live. The police have called it a suicide. Is that your view, too?’

Her face, if possible, stiffened even more. ‘My view? What do you mean?’

‘Well … that’s quite a brutal way of taking your life. Most people would choose another method.’

‘What do you mean? That he …? That someone pushed him off?’

‘Possibly.’

‘Surely the police would’ve investigated the case further, wouldn’t they? All they did was to talk to me – twice – and then nothing happened until I received a phone call telling me they’d decided it was suicide.’

‘And you were happy with that?’

‘If there was anyone who wanted to kill him it was that bitch, but he would’ve never let her in after all the trouble she’s caused.’

‘That bitch, as you call her. Are you referring to his ex-wife?’23

‘She was the one who started all the rumours about him. You can bet your bottom dollar she’s the one who reported him to the police, too. She wanted to make sure she kept the kids. And to do that, she used the dirtiest of all the lies.’

Her face had loosened up now. Muscles twitched, her eyes wandered from side to side and her whole body was in motion. It was obvious that this was a matter that engaged her. She made a powerful impression in all ways. A large woman she may have been, but there was nothing flabby or limp about her. She seemed more like a bundle of muscle, a well-trained heavyweight wrestler. I could truly imagine the energy with which she set about the floors as a cleaning consultant.

‘Right. Did they keep in touch?’

‘Touch! He was banned from visiting his children. If he was ever seen near where they lived in Frekhaug, she would ring the police. And she never showed her face out here of course, as I was trying to tell you.’ She shifted uneasily. ‘But now I’ve got to go.’

‘Wait a minute. If we assume the police are right – in other words, that it was suicide – did you notice anything that pointed in that direction, in the time before he died? Was he depressed, quick-tempered, unstable?’

She pulled a long face. ‘Depressed, quick-tempered, unstable? You talk like a social worker.’

‘Well…’

Then she appeared to remember something. Her expression changed, from aggressive to more thoughtful. ‘Though something did change in him after he received a phone call.’

‘A phone call? Who from?’

‘“Do you believe in demons, Svanhild?” he said. “Get away,” I said. “Demons?” “Yes,” he said. “As much as I believe in the devil and hell,” I said. Then Astrid came home from school and there was no more talk about that, until the evening when she’d gone to bed. “What did you mean about demons earlier today?” I asked him. Then he looked, like, well, scared and he said: “There’s a pastor coming here tomorrow. He can help me,” he said. “A pastor?” I said. “A bloody priest? What do you 24want with him?” “Well, he insisted,” he said, and so I said he should just ring and cancel, but then he didn’t want to talk about it any more. But I could see it was on his mind for the rest of the evening, even while we were watching a decent action film on TV. And the following day it happened.’

‘He fell to his death?’

‘Yes, but now I’ve really got to go. I must be at home when Astrid comes.’

‘OK. Mm … did you tell the police this? About the phone call?’

‘I don’t remember. Maybe.’ She stood up, took a big, dark-blue puffer jacket from the back of her chair and put it on. ‘You’d better ask them.’

‘Which school does your daughter go to? Løvås?’

She immediately leaned over me. Towering above me, her girth increased by the puffer jacket, with the nastiest expression I had seen since I was an army recruit, she made an even more aggressive impression than before, bordering on dangerous. ‘That’s got bugger-all to do with you. If you go anywhere near my daughter I’ll fucking well report you. Have you got that?’

‘Loud and clear,’ I said. Sergeant, I added, in my head, but that was where it stayed. No reason for any slips of the tongue.

With long, bouncing strides she disappeared from the café and left in the same direction from which I had entered the mall. I stayed put and finally tasted the coffee, which had died a silent death in the meantime, and tasted like it.

But now I had something to chew on. I took out my notepad and wrote a single word on it: Pastor. After some deliberation I added a question mark. I wanted to know a bit more about him.

6

Emerging from the mall, I stopped and looked around. In many ways I liked the way Fyllingsdalen was organised. Possibly that had something to do with the expanse of flat space, but it was much better laid out than the district to the north of Bergen, Åsane. This local mall was within walking distance for quite a lot of the area’s inhabitants. You could see them on their pilgrimages with their roller bags, all the elderly women – and some men – who had been to Oasen to shop or were on their way there. Young mothers with prams full of shopping and some students carrying plastic bags bulging with beer cans – and perhaps the odd soup packet or two – completed the picture.

The two high-rises by the cemetery towered up against the rear of Mount Løvstakken and the range of hills leading to the suburb of Krohnegården, and they were close enough for me to stroll along one of the paths in their direction. There was a chance I might fall victim to a flying tackle from Svanhild Olsvik, but I had to take that risk. After all, I was in a line of business where you had to be prepared to live dangerously.

When I arrived at the correct block, I took in the façade. This wasn’t the first time I had been here. In the early seventies, while I was still in social welfare, I had visited a woman here – Johnny-boy’s mother – who had been stripped of her parental rights. It wasn’t a happy memory, and I quickly repressed it.

At the front of the building the balconies faced west. Once again it struck me that I would probably have chosen a less brutal form of suicide than jumping from the tenth storey to the ground, without even considering that a young mother might be passing by with a pram, according to what Solheim had told me.

In my mind I tried to imagine him lying on the ground and the extent 26of his injuries. Had he landed head first, which would have caused fatal damage? On his side? Or on his legs, with no chance of remaining upright, like a pole vaulter after an unassailable world record, forty metres up … and down? A chill ran through me, at the mere thought of it.