7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Varg Veum

- Sprache: Englisch

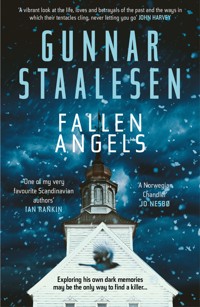

Ever-dogged Bergen PI Varg Veum is forced to dig deep into his own past as he investigates the murder of a former classmate. Vintage, classic Nordic Noir from international bestselling author Gunnar Staalesen. 'A vibrant look at the life, loves and betrayals of the past and the ways in which their tentacles cling, never letting you go' John Harvey 'One of my very favourite Scandinavian authors' Ian Rankin 'Masterful pacing' Publishers Weekly ***Now a major TV series starring Trond Espen Seim*** ________________ Exploring his own dark memories may be the only way to find a killer… When Bergen PI Varg Veum finds himself at the funeral of a former classmate on a sleet-grey December afternoon, he's unexpectedly reunited with his old friend Jakob – guitarist of the once-famous 1960s rock band The Harpers – and his estranged wife, Rebecca, Veum's first love. Their rekindled friendship is thrown into jeopardy by the discovery of a horrific murder, and Veum is forced to dig deep into his own adolescence and his darkest memories, to find a motive … and a killer. Tense, vivid and deeply unsettling, Fallen Angels is the spellbinding, award-winning thriller that secured Gunnar Staalesen's reputation as one of the world's foremost crime writers. ________________ Praise for Gunnar Staalesen 'Every inch the equal of his Nordic confreres Henning Mankell and Jo Nesbø' Independent 'Well worth reading, with the rest of Staalesen's award-winning series' New York Journal of Books 'Staalesen continually reminds us why he is one of the finest of Nordic novelists' Financial Times 'The Norwegian Chandler' Jo Nesbø 'Not many books hook you in the first chapter – this one did, and never let go!' Mari Hannah 'Chilling and perilous results — all told in a pleasingly dry style' Sunday Times 'Staalesen does a masterful job of exposing the worst of Norwegian society in this highly disturbing entry' Publishers Weekly 'The Varg Veum series is more concerned with character and motivation than spectacle, and it's in the quieter scenes that the real drama lies' Herald Scotland 'Gunnar Staalesen is a master of the PI genre, and with Fallen Angels he is at the top of his game' Live Many Lives 'It is a story full of mystery, of uncertainty and threat … a truly thought-provoking read' Jen Med's Book Reviews

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 525

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

When Bergen PI Varg Veum finds himself at the funeral of a former classmate on a sleet-grey December afternoon, he’s unexpectedly reunited with his old friend Jakob – guitarist with the once-famous 1960s rock band The Harpers – and his estranged wife, Rebecca, Veum’s first love.

Their rekindled friendship is thrown into jeopardy by a horrific murder, and Veum is forced to dig deep into his own adolescence and his darkest memories, to find a motive … and a killer.

Tense, vivid and deeply unsettling, Fallen Angels is the spellbinding, award-winning thriller that secured Gunnar Staalesen’s reputation as one of the world’s foremost crime writers.ii

iii

Fallen Angels

GUNNAR STAALESEN

Translated by Don Bartlett

FALLEN ANGELS

vi

As part of the story in this book takes place in an easily recognisable church in Bergen, primarily for geographical reasons, it is appropriate to emphasise that both the priest and organist of this church, along with all the other featured characters, are purely products of the author’s imagination and have no connection with reality.

—GS

viii

ix

‘And suddenly everyone went quiet because they discovered there was bright daylight outside, even though it was midnight, and that the Angel Gabriel – his arms raised against the wall like an espalier – was watching them silently through the window “with eyes more beautiful than wine”.’

—Alain-Fournierx

CONTENTS

1

The funeral took place on a Friday. It was ten days into December and the air was grey with sleet.

I met Jakob Aasen outside the chapel. At first I hardly recognised him. He had grown a beard and his dark, tightly curled hair was speckled with grey.

For an instant we stood looking at one another. Then he smiled tentatively, while I nodded a kind of acknowledgement.

‘Varg?’

I nodded. ‘Jakob…?’

We shook hands.

‘How long is it since we…?’

I shrugged. ‘1965.’

‘Yes, but … surely we must’ve seen each other since then.’

‘Couple of times in the street maybe. By chance. Have you been in Bergen the whole time?’

‘More or less. And you?’

‘Yes, at any rate since 1970.’

‘Sixteen years – and we’ve barely seen each other.’

‘How many of the others from the class have you seen?’

He looked around. ‘Well, now you’re asking.’

‘Life’s like that. We all go our various ways, following the beaten track to the water hole and back, year after year. You can live a whole life in Bergen without meeting a classmate who lives two blocks along. He goes one way, to his work. You go another. And never the twain shall meet.’2

He smiled wryly. Again he looked around. ‘It’s sad about Jan Petter. Do you think any of the others will come?’

‘Paul Finckel’s down there, struggling up the hill.’

‘Paul. Is that Paul?’

‘Mhm.’

We watched Paul Finckel dragging his flabby body up the hill from Møllendalsveien to the chapel.

‘He’s a journalist, isn’t he?’

‘Yep. And he’s not getting any younger either.’

He angled a look across at me. ‘No?’ Then he nodded. ‘Yes, the years take their toll.’

I looked at him. He was bowed and his round, cherubic face was greyer and baggier than I remembered. But I recognised the lively, brown eyes. They were just the same, both cheerful and melancholic.

The years had left their mark on us all. The furrows in my own face were even more pronounced this year. After every season new cares and woes are reaped, and old Farmer Time has to plough even deeper with every year that passes.

‘And what do you do, Varg? I think I heard somewhere that you…’

‘You probably heard correctly. I’m a sort of private investigator.’

He smiled as he shook his head. ‘Well, that shows how little we actually know. About how people will end up, I mean.’

‘Right. And you?’

‘I work as an organist. And I do a fair bit of composing.’

‘As an organist? In a church?’

He nodded. ‘In a church.’

‘You said it yourself. How little we know. In other words, you’ve hung up your rock ‘n’ roll boots?’3

A sad smile settled on his lips, but took flight again at once. ‘Yes, I suppose I have.’

Paul Finckel had made it up the hill. He wiped the sweat from his brow with a handkerchief large enough to cover several local corruption scandals. He was wearing a puffed up, dark-blue down jacket that made him look as if he might take to the air at any minute. We were all attired according to our personalities. Jakob was wearing a sober, light-blue, knitted Shetland cardigan. I was wearing my newest winter coat, one from 1972.

Finckel greeted me. ‘Hi, Varg. There’s one thing I’ve been wondering. Why do they always put burial chapels at the top of mountains in this country?’

I looked up at Mount Ulriken, which towered six hundred metres above us. ‘The top’s up there, Paul.’

‘That’s how it feels, anyhow.’ He looked at Jakob, and then it must have dawned on him who it was. ‘Jakob? Jakob Aasen! Well, I’m buggered. What are you doing with all that fuzz on your face?’

Jakob grinned and looked around. ‘Shh! I’m here on a secret mission.’

Finckel’s lower lip jutted out. ‘I see. An agent for The Harpers?’

‘Exactly,’ Jakob said, his smile slowly fading.

‘What about Johnny? Isn’t he coming?’

‘No idea. I haven’t seen him for … ages. Besides Johnny isn’t the type to go to funerals, if I can put it like that.’

‘No, I suppose he isn’t. He’s keener on draught beer than the funeral bier, if you ask me.’ Finckel turned to me. ‘And the master detective is fine? No new corpses on your horizon?’ He lowered his voice. ‘Jan Petter wasn’t…’

‘You should know,’ I said. ‘There was an article about him in your paper.’4

‘I don’t read such rags,’ Paul Finckel said.

Jakob interrupted: ‘Do either of you know what he died of?’

Finckel nodded. ‘He fell from some scaffolding. He was a builder. Eighteen metres, straight onto concrete. Didn’t even have time to say the Lord’s Prayer.’

That silenced us – all three.

The doors opened and people began to drift into the building. The entrances to the two chapels faced each other. The smaller chapel was called Hope. It was for the select few. The bigger one was called Faith and was reserved for the great, white flock. This division wasn’t apparent during your ordinary Norwegian church service on an ordinary Sunday morning. But that is how death is. It upsets so many notions.

The service for Jan Petter was to be performed in Faith and the room was roughly half full. At the front on the right sat close family. He had a wife and two teenage children. I recognised his parents: white-haired and leaden-limbed in their sudden grief. The rest of the congregation appeared to be wider family, work colleagues and neighbours. A trade-union flag had been placed against one wall. The coffin was adorned with a large arrangement of pink roses and the floor in front strewn with wreaths and bouquets.

The chapel was fifteen years old. The interior featured light-coloured wood and grey concrete, with natural stone cemented into the walls. Above the pulpit hung a simple, black, wrought-iron cross.

Outside the tall windows, the wind took hold of the rhododendron bushes and the bare trees. Bergensians had their own special word for this kind of weather: valleslette – two or three degrees above zero, greyish-white sleet and a biting wind from the south-west.5

The priest came in and took a seat. Up in the gallery behind us, a lone violinist played a sad melody I was unable to place.

I discreetly cast my eyes around. There were only us three from our old class. Perhaps some of them no longer lived in Bergen. Perhaps others hadn’t seen or hadn’t reacted to the death notice in the papers. The rest clearly couldn’t take the time to accompany him on these, his first steps into the school corridor, on his way to see the headmaster.

The melody came to an end. The priest rose to his feet. He was a relatively young man, with a childlike face, big glasses and a fringe. To me he looked more like a confirmand than a chaplain. But his voice was deep and commanding as he said: ‘Today we are gathered here together, beside Jan Petter Olsen’s coffin…’

And my thoughts drifted back in time, to the classroom. Once again I visualised the class of almost thirty boys who had been together for seven years at the folkeskole, from 1949 to 1956.

My seat had been by the window with a view of Pudde fjord. When the lesson was too boring my eyes strayed outside, to boats of all sizes as they pitched and rolled past: tugs, the ferries to the island of Askøy, freighters and passenger ships. They were setting off for exotic places, such as Kleppestø, on the southern coast of Askøy, and Rio de Janeiro, and they returned with an ineluctable image of dried fish and bananas. The smell of both. The ineluctable sight of tied bundles and white wooden crates with blue and yellow customs labels. One was loaded; the other unloaded. Boathouses with cranes and hoists, reminiscent of gallows. Sliding doors that opened onto nothing, only air. All of us, our eyes on stalks, on the edge of Nordnes park, safely behind a fence, miles from both Kleppestø and Rio.

The class around me. Jakob sat at the front. He lived on the outer edge of the school catchment area, at the bottom of 6Skottegaten, on a corner facing Claus Frimannsgate. He played the piano and always got the best grades. Then there was Benny, whose real name was Bernhardt and who was the class tough guy: he carried ten kilos more than most of us, smoked when he was ten, drank alcohol when he was thirteen, went to sea at the age of fifteen and later ended up as Bergen’s most reliable digger driver. And then there was Paul Finckel, who sat at the back, plump and short of breath, even then a wit, who played to a riotous gallery with his cheeky comments. And there was ‘hi-how’s-it-hanging?’ and ‘to-hell-with-it!’ Helge, the charmer, who was the first of us to go the same way as Jan Petter, when he fell into a cargo hold while unloading goods in Liverpool one day during Easter 1964. And there was gentle, dark-haired Arvid, so reflective that he died of cancer at thirty-six years of age. And Pelle, who lived in the same street as I did and was my best pal in those days. The two of us set up everything from secret gangs to detective agencies, from boys’ marching bands to cycling clubs, before our fathers’ careers brought that to a halt. Pelle and his family moved to Fredrikstad and we never saw each again. There were at least twenty others, big, small, auburn, blond, freckled and chubby. When we posed for the class photo, we looked like any other boys of that period: dressed in thick cardigans, sweaters and windcheaters, breeches made out of our fathers’ Sunday trousers from the thirties. To show respect for the photographer we held our woolly hats in our hands, those blue hats with a bluish-white stripe along the turned-up brim – the colour ran in the wash – or plain, grey hats minus the bobble, torn off in a fight. No one had inked a black cross above our heads. No one had told us when we would die.

The congregation sang: ‘Lead kindly light, amid the encircling gloom, Lead thou me on.’ It was a hymn I remembered from 7music lessons in the days of yore. ‘The night is dark, and I am far from home; Lead thou me on.’

Beside me, Jakob Aasen sang in a ringing tenor: ‘Keep thou my feet; I do not ask to see the distant scene: one step enough for me.’

On the first pew someone was sobbing quietly.

When one of us died it was as though we were still sitting in the same classroom, at some point midway through our schooling, in the fourth or fifth class. Most of us were still sitting at our desks. The chairs for Helge and Arvid had already been empty for several years. Now Jan Petter had risen to his feet and left us. One by one, we would be called forth, as if summoned by the school dentist for a check-up. One by one, we would leave the room until all the chairs had been vacated and the great headmaster came to send some of us up to the art room on the top floor and the rest down to the boiler room in the basement.

The young priest spoke. Then there was more singing: ‘Love from God, our Lord, has forever poured, like a fountain pure and clear…’ The hymn took me back to the times when Rebecca and I had sat together in the gallery of the parish hall where her father, the lay preacher, spoke, voice a-quiver, about redemption and perdition. Rebecca, who had weaved in and out of my life, who moved hither and thither, from when I was four until I was more than twenty, a girl I didn’t even need to close my eyes to see, from when she was five years old, in a cardigan with metal buttons, until, at eighteen years old, she just sat there waiting for me, until I leaned forward and circumspectly kissed her. ‘Who in love remains, peace from God obtains; God Himself is ever love.’

The coffin was lowered and the priest spoke: ‘Earth to earth, ashes to ashes, dust to dust.’ Three handfuls of earth fell with a thud on Jan Petter’s coffin. Now silent tears flowed on the front pew. Shoulders shook and someone mumbled something or 8other, quietly to themselves. ‘In the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost. Amen.’

We sang ‘Beauty around Us’. The solo violinist played ‘In Moments of Solitude’ by Ole Bull. Jan Petter’s widow and his two children were at the front and laid a rose each on the lowered coffin before walking out into the Vestland winter.

The rest of us followed at a respectful pace.

As I passed the coffin I stopped for a few seconds. The door to the corridor had closed behind Jan Petter. Soon the school bell would ring.

The question you involuntarily ask yourself is: Who will be next? Will it be my turn?

That is how it is. You never know when you will be called to see the school dentist. And you never know when you are going to die.

2

We stood outside the chapel. None of us looked at one another directly; no one wanted to take the initiative and leave. By the front door Jan Petter’s widow, eyes red-rimmed, was receiving the last mourner’s condolences with a limp handshake. The sleet landed on our shoulders like colourless confetti.

Even Paul Finckel’s strident sarcasm had dwindled to nothing. ‘Anyone want a lift into town?’

‘I’ve got my car here,’ I said.

‘What about going out for a beer, all three of us? I just have to nip down to the newspaper.’ Finckel looked at Jakob.

‘That’s an idea. I have to go home first and take care of the kids.’

‘Where do you live?’

‘In Nygårdshøyden.’

I looked at Finckel. ‘I’ll drive Jakob down. Where shall we meet?’

‘We might have to drive our youngest daughter to my sister’s,’ Jakob said. ‘She lives in Sandviken.’

‘Call me when you’re ready,’ Finckel said. ‘I’m at the paper. It’s pretty central as far as all the important watering holes are concerned.’

‘That’s why he works there,’ I added.

‘There are worse reasons,’ Finckel grunted, and left.

We followed him down to the car park.10

*

We drove in silence from Møllendal, crossed Gamle Nygård bridge and took the illegal left-turn the new traffic arrangement almost invited you to take, to Marineholmen, on the southern side of Nygård Park.

Jakob explained where he lived. Halfway between St John’s church and Sydnæs Battalion marching band. The decibel level rose considerably in the spring as Easter week approached, with the pealing of bells at all times of the day and the band doing their drills every Tuesday and Saturday.

‘How many children have you got?’ I asked as we passed the football ground in Møhlenpris.

‘Three,’ he answered. ‘Though they’re not all children really … Maria’s sixteen. Then there’s Petter, who’s fourteen, and little Grete, who’s six. She’s the one who’s the problem if Maria can’t look after her for a few hours.’

As we turned up to the top of Olaf Ryes vei, he said: ‘My wife’s … moved out.’

I nodded, but said nothing.

The building where he lived was in the middle of the district. It had a redbrick façade and faced the shadowy side of the street. Jakob lived on the first floor in two flats that had been merged into one.

Midway up the dark stairwell he stopped with one hand on the railing, half turned to me and said pensively: ‘How do you get on with Jesus, Varg?’

The unexpected question made me feel like a turtle that had been whipped onto its back and deprived of any protection. I mumbled: ‘Well, I …Why do you ask? Are you related?’

He scrutinised me. Then he shot me a gentle smile. ‘It’s 11strange, meeting you again after such a long time. A lot of water’s flowed under the bridge, eh?’

I nodded in agreement. A lot of water indeed.

Then he carried on up. He rang the doorbell as he put the key in the lock and held the door open for me.

We went into a long, dark hallway. On the floor was an open, light-brown leather satchel. Shoes and boots were strewn across the floor and on a chair there were piled four or five jackets of various sizes and styles. On a little chest of drawers I espied an old-fashioned black telephone under a stack of brochures, free newspapers and unopened junk mail. Somewhere nearby I felt the monotonous throb of disco rhythms.

The door to a blue kitchen was open. Plates, cups, glasses and breakfast items were still on the table and a somewhat sickly smell of rancid fat and stale carrots wafted out to us.

Jakob closed the kitchen door and opened another, to the sitting room. ‘Come in, Varg.’ Then he shouted: ‘Maria! Are you at home?’

After an unhurried pause a door opened further down the corridor and the pop music became louder. ‘What’s up?’ a young girl said.

Jakob’s voice was drowned out as he advanced down the corridor.

I looked around the large sitting room, which was L-shaped as two rooms had been merged and the dividing wall replaced with a big, white sliding door. At the back, on wooden flooring treated with lye, there was a black grand piano surrounded by rag rugs and black-and-white pictures on the walls. One wall was covered with shelves of books and sheet music, and inside a half-open cupboard I glimpsed a not inconsiderable collection of records and cassettes.12

The part of the room I was in now was full of contrasts. The majority of the furniture was old-fashioned, in a kind of imitation baroque style, with ornate legs and upholstered in a smooth, brown-and-green patterned material. Two modern, black leather armchairs, two others in a burlap fabric and a child’s spindle-back chair completed and reinforced the impression of a lack of system.

In the traditional sixties style wall shelving were a radio, a record turntable, a CD and cassette player and in the middle of the floor a TV set with a VCR underneath. Beside the bow-legged baroque sofa was a rack crammed full with newspapers, and in all the free spaces, on the wall shelving, the table, floor and shelves were piles of newspapers, magazines, books and sheet music. Strewn across the floor were Lego blocks, dolls, Playmobil pieces, sketch pads and crayons in the most delightful chaos I had experienced since I was divorced.

The mixture of style and content was apparent on the walls as well. Crucifixes and icons hung side by side with graphics by Elly Prestegård and Ingri Egeberg, a watercolour by Oddvar Torsheim and a Hardanger landscape. A pavement artist had sketched the three children at various points in their short lives. All three looked as children do in such sketches: like tourists to life before their visas run out.

The eldest child was entering the sitting-room now, with her father.

Maria wore grey jeans and a pink jumper. Her hair was fairer than Jakob’s, but she had the same round facial features he’d had. Her eyes were blue and ill at ease, her mouth was adolescent, and she wore a pink lipstick and blushed becomingly when her father said: ‘Say hello to Varg, Maria. He’s an old classmate of mine.’13

She passed me a limp hand and mumbled something incomprehensible. Then she beat a hasty retreat to her room.

‘She‘s going out,’ Jakob said awkwardly, as though he still hadn’t got used to his daughter making arrangements he no longer authorised. ‘We’ll have to pick up Grete from the crèche and take her to Åse’s. I’ll ring her and ask if that’s alright. Petter can look after himself when he comes home. I’ll leave a note for him.’

He cast around, heaved a pile of newspapers to one side with his foot, gave up trying to create a better impression and went out to make a call.

Åse?

I tried to remember his sister, but I could barely recall that he even had one.

While he was talking on the telephone, I picked up a magazine and leafed through. It was one of those literary journals where you need to be relentlessly academic in order to work out the layout and require a degree in semiotics to understand a word. I studied the pictures.

Jakob reappeared in the doorway, carrying a plastic bag in one hand. ‘That was fine. Shall we go?’ He shouted down the corridor: ‘Bye, Maria.’ But the only response came from a-ha. He shrugged and guided me back out through the door. ‘Kids,’ he muttered.

We picked up his youngest child from the crèche by St John’s church. She was wearing a dark-red raincoat, with long yellow cuffs to protect her hands from the rain, and blue-and-white rubber boots. Her cheeks were flushed and gooseberry jelly ran from both nostrils. She smiled as she met us, revealing two missing front teeth.

Her shyness was different from her sister’s. She didn’t blush, she 14watched me from the corner of her eye all the way from the gate to the car. In one hand she was holding a blue plastic bucket with a handle that had come away on one side. In the other, she was holding the wettest teddy bear I had ever seen. ‘She won’t let it go for an instant,’ Jakob mumbled. ‘I have to wash it when she’s asleep, otherwise she’d insist she went into the washing machine with it.’

Jakob’s sister lived in a street off Nye Sandviksvei with a man who worked on oil rigs and a Saint Bernard that had to be at least a hundred years old. It barely batted an eyelid as we passed it on the stairs. ‘Åse hasn’t got any children,’ Jakob said, as if that explained everything.

Åse opened the door and I still didn’t remember her. She was ten years younger than us and as such belonged to a different generation. Now she was a new experience: tall, wearing a colourful plaid smock, light-brown elephant cord trousers and grey felt slippers. She was the archetypal mamma and I had an inkling why her beaming smile never seemed to reach her eyes.

We shook hands and of course she didn’t remember me. Neither of us gave the impression we had missed anything.

She and Jakob agreed that Grete might as well stay the night.

Then we drove up to Stølen and parked the car. That was the last thing we did while still in full control of ourselves. The next few days passed on autopilot, as they often do when you have lost all ability to make decisions.

3

We started gently, each with a beer, in a bar reminiscent of a folk-craft gift shop, from the hard, wooden benches to the buxom waitresses. The faces around us were plump and bland, either because they were young or because their owners had drunk too much beer. There was a buzz of conversation around us.

‘How long’s it been, Varg? Since we last saw each other properly? I mean, talked?’

‘Since 1965.’

His eyes assumed a faraway look. ‘1965? Can you really remember that with such accuracy?’

I nodded.

‘1965,’ he said. ‘Johnson was president of the USA. The Vietnam War was escalating. The Beatles brought out Rubber Soul. The Harpers were at the peak of their career, and you and I…’

‘Had gone our separate ways.’

He beckoned for two more beers and they arrived at the table before the froth had had time to settle.

‘Odd how life goes in circles, Varg. We could draw geometrical shapes. Find where they intersect.’

‘In the strangest of places.’

‘You’re right. In the strangest of places.’

‘How did it all end with The Harpers?’

He didn’t answer straightaway, but hummed the tune of one 16of their most popular songs and finished it on an ugly, dissonant note. ‘But we had some good years, Varg.’

‘In The Harpers?’

He grimaced. ‘You and I. Before, I mean.’ He took a swig. ‘I often think back on childhood as the only truly happy time in our lives.’

‘You may be right about that.’

‘No responsibilities, no worries, apart from someone threatening to beat you up after school, but we knew from experience this would pass. By the following week all these things would be forgotten.’

‘Yes, often as not.’

‘The seasons, Varg. They were as long as eternity. Winters, we would go tobogganing in the streets where there were hardly any cars. Or hang on to the back of the Minde bus down to the big Klosteret square, and for another few hundred metres, if we were really lucky.’

‘We used to call it bumper skiing.’

‘Yes, that’s right. And the summers when we swam in Nordnes from the seventeenth of May. Springtime with all the street games, autumn with bike trips to the orchards in Minde. All…’ he puckered his lips and said sadly ‘…gone.’

‘Remember how Paul would sit at the back of the class and make cheeky comments? And how Bergesen had an extra-long pointer made by the woodwork teacher so that he could whack Paul around the head from his desk?’

‘Paul, yeah. Let’s give him a bell, shall we?’

‘Good idea.’

‘I’ll do it.’

While Jakob was phoning I allowed the atmosphere of a country & western festival to wash over me. Most of the people 17around me were half our age and belonged to the v.b.c. generation: videos, beer and crisps. A spare tyre was their trademark; they were sitting knees akimbo and horseless, knocking back the beer one early winter afternoon in this western saloon. Outside, darkness had fallen, a grizzled grey because of the sleet, artificially suffused by Bryggen’s toxic-yellow street lighting.

Jakob returned with two more beers. ‘Paul will be round soon.’

‘He’s been round for years,’ I said. ‘He looks like he’s permanently six months’ pregnant.’

Jakob shook his head. ‘To think Paul’s a journalist. Well, he was never short of a witty word. But I always saw him as a grocer. What do you reckon?’

‘Grocers are a dying breed. Not even the RSPCA’s worried about them.’

‘And you…’ He studied me with cheery distrust. ‘Surely you don’t call yourself a detective, do you?’

‘What do you think I should call myself? A consultant?’

‘Why not? A private-investigation consultant. No, I know: a crime consultant. Doesn’t that sound more confidence-inspiring?’

He leaned forward. ‘So if I needed help one day … all I’d have to do was call you.’

‘Fine, as long as you don’t call me a private dick. I’ve been called that a few times already,’ I said, downing a mouthful of amber nectar.

A shadow fell over our table. We looked up. There was Paul Finckel, hips swaying and hands splayed out to the side to represent a tutu as he burst into an old Bergensian song: ‘Ingeborg, she…’

Jakob joined in the refrain: ‘Ingeborg…’18

At the neighbouring table two youths clapped their hands loudly, more for exercise than out of any enthusiasm. Paul Finckel turned around anyway and gracefully acknowledged the applause, raised a finger for ‘a beer, no, three over here, frøken, for me and my friends’, then dropped down heavily on the vacant part of the wooden bench where I was sitting.

‘What’s the deal?’ he asked, looking around.

The deal was three beers and off to the next bar, a little further into Bryggen. Here the clientele was older, drinkers were more hardened and it was possible to have a conversation without being assaulted by music.

Like in Alice in Wonderland, we didn’t just drink from bottles that made us smaller than we were, we became younger too. Around the table with the checked cloth we shrank into three young boys, caught somewhere in the critical vacuum between ten and thirteen, ready to launch ourselves into life’s mysteries.

Paul Finckel regained the hair he had lost on top, recovered the Elvis quiff that his thin hair had never quite been able to emulate, sat at his desk at the back with the eternal half-smirk on his lips, a thorn in every teacher’s side and a joker for whom success was predestined. He moved back into Abels gate, the short, steep street between Nordnesveien and Haugeveien, the middle son of three, but the only one with innate wit, the brother of two sisters, all the children of an electrician called Per, and he had a narrow, rectangular face beneath a mane of fair hair, which gave rise locally to the inevitable nickname of Lys-pæren: the light bulb.

Jakob Aasen became beardless and pimply from a very young age, a thoughtful model pupil from Claus Frimannsgate, son of a shop assistant in a respectable gentlemen’s outfitter’s and a mother who taught the piano, at home.19

‘Are your parents still alive?’ I asked.

‘My mother’s dead. That’s her grand piano I have. My dad’s alive though. But the shop where he worked has been bought up by the fashion people, Bik Bok.’

Paul Finckel burst into loud laughter. ‘Do you know what Oddvar Torsheim, the artist, once said to me during an interview? “I can’t talk to anyone wearing a Bik Bok T-shirt. When I first saw the words emblazoned on his chest, I thought it was his name.”’

We laughed with him.

And me?

I was the only son of a tram conductor who studied Norse mythology in his free time and for whom the greatest moment in his life was giving his name to his son. I moved back to the crooked, green house, in the middle of an alley where there was now a block of flats and a rough-and-ready football pitch, straight across from Anita, who had the tightest sweater and biggest baps in the street, excluding all the forty-plus heavy-weights with their pre-war jugs and windowsills strong enough to support them when they were leaning out and chatting with the neighbours. On dark autumn evenings my eyes were glued to the illuminated blind over the window where Anita undressed, in the hope that I might glimpse a silhouette, a hope which was dashed forever when she became pregnant with Johnny’s child, moved to Paddemyren and took an unretractable step into adult ranks.

‘What are you thinking about, Varg?’ Finckel asked.

I returned to the present. ‘You wouldn’t believe me if I said.’

‘I believe most things about you.’ His eyes glinted indecently. ‘It seemed to be doing you some good at any rate.’

I got up and nodded towards the toilet. ‘I’m just, er…’20

‘Was it that good?’ Again peals of laughter.

I looked at them, from above. Jakob and Paul. We hadn’t exactly been the three musketeers and it was more than twenty years ago. But perhaps this would be our last evening together.

I had stopped counting the beers, I was getting more and more drunk, and I felt as light as an elephant in a parachute. The room felt warm and cosy, with the large wall-paintings of Bergen harbour, the brown partitioned stalls and the straddle-legged waitresses, who seemed to have been there forever. A chorus of growling voices, like good-natured bears waking up, rose and fell, and were gone as the toilet door slammed behind me.

A man in his mid-fifties was bent over one of the urinals. His shoulder-length hair fell untidily over his forehead, a deep, reddish-brown scar ran diagonally from one bushy eyebrow and his wet mouth was surrounded by fox-red stubble, stained with nicotine. He stood with one hand on the wall to steady himself and the other holding tightly on to the leaning tower of Pisa as though it were the only thing worth clinging to in life.

When I entered, he looked up and said, ‘Schlompfssmrrf.’

‘I quite agree,’ I said.

‘Varsjågorogknfff,’ he continued, with great conviction, while addressing my knee.

I did my duty, buttoned up and asked if I could help in any way.

He was so taken aback that he almost fell over. But his other hand came to the rescue and he managed to retain his balance. For the first time I understood what he said: ‘Hrrschlemme-n-peace.’

I nodded, said, enjoy the rest of your day, and rejoined the others. They were ripping the reputations of local politicians to pieces.21

Paul Finckel had decided he wanted to go dancing. ‘I feel like a bit of hokey-cokey,’ he leered.

Jakob’s head was beginning to loll to the side. ‘I can’t remember the last time I had a dance,’ he slurred.

‘The last time I did doesn’t bear remembering,’ I said.

‘Come on,’ Finckel said. ‘It’s not as alarming as it sounds.’

Hesitantly, we drained our glasses and found our way into the fresh air. Great dollops of sleet were falling, as if breathless angels were blowing misshapen soap bubbles into the town through their trumpets.

Bergen was like one big Christmas parcel. Spray-painted spruce branches glittered, light bulbs swayed overhead, Santas sat in kitschy shop windows where price tags dominated rather than the items, and from camouflaged speakers blared songs and carols that sounded like canned recordings of bygone children’s parties. All the way up Torgalmenningen they had planted the annual forest of yule trees, and the Salvation Army, busily collecting clothes a few weeks before Christmas, was lightening the load for the City Refuse Department.

Finckel led the way – across the market square and back in time. ‘Do you two remember when we used to go dancing in Viking Hall; to the Espeland Hall or on the Askøy ferry to Bergheim; or at Kjøbmannen where all the special Easter brews had made their first appearances? Well, you, Jakob, you went everywhere, didn’t you.’

Jakob nodded. ‘There isn’t a dance venue in Bergen and the region I haven’t played at. But of course we saw everything from a slightly different angle, those of us on stage.’

‘If I had wings, I’d fly – with The Harpers to the sky. With The Harpers to the sky,’ Finckel wailed. Then he came down to earth. ‘But, you, Varg, you weren’t often with us, were you?’22

‘Oh, yes, I was, but maybe not with you, Finckel.’ For some reason I couldn’t warm to the idea of using his Christian name. He went through life as a Finckel and Finckel was what rolled off my tongue.

But he was right. I seldom went to dances. In those years I preferred the Saturday meets at the parish hall where Rebecca’s father held forth. And many more years were to pass before I went dancing with her…

We stood in a queue somewhere. Finckel was telling jokes non-stop while Jakob was swaying in heavenly harmony. In front of us Saint Peter in doorman’s uniform was checking that we were wearing a tie and letting in a few at a time.

When we were finally allowed through the eye of the needle we felt like camels at the end of a long desert trek. But before we had entered properly, the music blew our hair back, and even Finckel was almost knocked off his perch.

We worked our way forward to a round table at chest height where the three of us could stand, and Finckel fetched three tall, narrow glasses of pils from the bar. ‘It’s half a litre, even though it doesn’t look like it,’ he shouted.

‘Is there a surcharge for height?’ I shouted.

He opened his palm and examined the change. ‘And a luxury tax, it seems.’

Jakob leaned forward and shouted, a little less loudly: ‘Be honest. Aren’t we a bit old for this?’

We looked around.

We were definitely at the top end of the age scale. Most of the girls would have preferred to dance with other girls than with us. The noise from the sound system was ear-piercing, penetrated our bones and rocked us back and forth, from side to side, back and forth, side to side, in a way that aged us prematurely, 23pursued us to the bottom of our beer glasses and back to the bar for another. We were like terrified aquarium fish in a pool reserved for sharks.

On the street again, the queue of young people laughing at us behind our backs, Finckel immediately admitted his mistake. ‘Sorry, boys. I misread their ID. I should’ve scrutinised their dates of birth more carefully. Wax Cabinet next. That’s where our ladies hang out …’

But when we arrived at the place known locally as the Wax Cabinet, what Finckel called our ladies were already in action.

We squeezed onto a table for two beneath a palm tree covered with artificial snow and subjected the room to our searching gazes.

At least they were doing dances we knew the steps to. A three-piece band with a beat box and keyboard sang ‘Fjellveivisen’, a Bergensian love song, with a swing rhythm and an Italian accent. The vocalist was definitely from Knarvik, but his two colleagues more likely hailed from Naples than Nordnes.

‘You know what they call that keyboard, or remote keyboard, as it’s known technically, don’t you?’

‘No, tell us.’

‘A chick-catcher. After they came onto the market, they made it easier for the pianist to pick up girls from the stage.’

‘I can feel the mike’s calling you,’ Finckel grinned.

Jakob shook his head. ‘Oh, no. Not anymore. It’s when I see and hear stuff like this I’m happy we stopped when we did.’

‘How long did you keep going?’ I asked.

‘Until the mid-seventies.’

‘Johnny’s still at it,’ Finckel said.

Jakob grinned wryly. ‘Johnny was different from the rest of us. For him there were only two options: going on or hitting’ – he pointed to the floor – ‘rock bottom.’24

‘Why did you stop?’ I asked.

His eyes moved in my direction, snatched a quick look and then carried on. ‘We … just stopped.’

‘Waiter!’ Finckel shouted with a hand raised.

A small, dumpy waiter with dark curls and thick horn-rimmed glasses gave us a grease-stained menu each and left us to study our exotic culinary travels for ten minutes before returning to note down our destinations. After ordering we went back to our beers.

Our ladies were still in action. They were dancing like young girls. What was sad about them was that they danced like young girls had done thirty years before. If they had gone to the place we had just left, they would have been regarded as ancient relics of the Silurian period. But they knew they had passed their prime and were enjoying themselves.

‘I have a theory,’ Finckel said. ‘The only one of us three with a real chance here is me.’

‘Oh, yes?’ I said, looking around. At the table beside us sat a woman of my age, with a beautiful but inebriated face, on which time and anxiety had left their marks, like birds’ feet in virgin snow. She had a lit cigarette hanging from the corner of her mouth, and for a moment I thought I had caught her eye, before I realised she was staring at the empty space between us.

‘You, Jakob, look much too youthful with the bush you’ve grown on your mug,’ he continued. ‘And you, Varg, my lad, you’ve got a bit too much spring in your step. These ladies here, whose bodies haven’t quite withstood the ravages of time, and certainly can’t take strong lighting, they prefer to see themselves reflected in a body that’s even more run-down. That’s why they’ll choose one like mine,’ he said with a proud smile, gripping his stomach and hoisting it, then carefully letting it fall back over his belt.25

‘So we should’ve stayed where we were, in other words?’ I said.

He laughed. ‘No, no, no. The age gap was too great. Two ladies in their thirties would be right for you.’

‘Do you know any?’

‘Yes, if you like them well used.’

‘That’s typical of you.’

Soon afterwards he was dancing with the woman from the adjacent table. She floated like an unacknowledged ballerina between his short arms, but her head was way, way back and they communicated only with their lower bodies.

Jakob and I drowned our lost youths in two more beers, tucked into burnt steaks and overcooked cauliflower and our heads felt heavier and heavier. It had been a long day, as days that start with a funeral are wont to be.

‘I remember once when we were in upper secondary, Varg. There was a whole gang of us who went to Neptun after a society meeting – the last one in the spring, in May. They had some lilies on the table. You put a bunch in your beer glass and asked: ‘Do you serve beer in vases here? Not long afterwards we were asked to leave.’

‘We were often asked to leave in those days.’

We finished eating. For dessert we ordered two more beers. Paul Finckel had ordered another well before us and sat down at the adjacent table, which made the woman he had been dancing with appear even more nervous and drunk.

Jakob eyed me inquisitorially. ‘You’ve gone so quiet, Varg. What’s on your mind?’

‘I was thinking back to … those days.’ I smiled sardonically. ‘To the girls we knew.’

‘Who in particular?’26

‘Well, various girls.’ I ran my eyes around the room.

‘Can you see any of them here? Would you like to dance?’

‘No, I’m afraid these ones would be too old, even twenty-five years ago they would have been.’

‘Perhaps we should leave?’ Jakob slurred. The beer was having an effect.

‘Maybe.’ Actually my vision was blurred too. I stirred the beer with my forefinger. ‘Why did The Harpers stop, Jakob?’

‘Why do you ask?’ he said with a sudden jerk, like a dog trying to release itself from its chain.

‘Well, I—’

He interrupted me. ‘We were too old. Our interests were going in different directions.’ He turned to the side, as though to indicate that he didn’t want to talk about the subject any longer.

‘What happened to you all?’

He turned back and smiled drily. ‘I’m here.’

‘I can see that. And Johnny’s still singing?’

He nodded and looked past me. ‘Johnny’s singing. We could…’

‘Yes?’

‘Well, I don’t know. He’s singing this evening, at Steinen. They have oldies performing there every Friday.’

‘Oh, yes? Do you feel like going?’

‘Not really. On the other hand, well, alright. Let’s do that. I’ve got something I…’ He didn’t finish the sentence. Instead he sat lost in his own thoughts.

I enticed him out. ‘What about the others?’

‘Which others?’

‘In The Harpers.’

‘Do you remember them?’

‘Of course I do.’27

He leaned across the table. ‘You were never at the dances, Varg.’

‘They were all from the same…’

‘Why didn’t you…?’

‘…school.’

‘…go?’

I studied him more closely. There was a combative expression on his face. ‘Because.’

‘Because?’

‘Because I was spending a lot of time with someone who didn’t go to dances, either.’

He snorted.

‘But that doesn’t mean I didn’t see you all. Have you forgotten that I helped to hump your gear for you sometimes? Once out in Salhus, once in Espeland Hall and once we went all the bloody way to Rong, which involved taking two ferries and a succession of buses.’ And they had stood on the stage, in the brightest lighting since God created the world, and played as if they had Lucifer himself at their heels.

The Harpers. 1959. Johnny in a Hawaiian shirt and black, Terylene trousers, DA at the back, hair as if he had shares in Brylcreem, his wrist, chin and hips twitching and shaking like Elvis, a voice as loud as a foghorn and a hand like a steam hammer on a red, shiny guitar: a typical three-chord man thriving on sex appeal and testosterone, even then. Jakob was two steps to the side of Johnny and half a step behind, also brandishing a guitar, but with a much better technique, his hair pressed flat to the scalp in a desperate attempt to tame his rampant curls, a white shirt, a Slim Jim tie and a snakeskin jacket like the one Brando wore in The Fugitive Kind, full-blown pimples on his face and down his neck and a backing voice he 28had probably learned from Torstein Grythe’s boys’ choir. And on the flanks: Harry Kløve on bass guitar and Arild Hjellestad on drums.

‘They were in the class below us, both of them,’ I said.

He nodded. ‘Correct.’

‘Harry Kløve was dark-haired and skinny, like that skater, Roald Aas, only with slicked-back hair. He didn’t say much, but played like a jazz guitarist. He was the only man in the band who came even close to you.’

‘A natural.’

‘Arild Hjellstad on the other hand…’

‘What about him?’

‘A chubby little monkey. Arms too short to ever become a drummer of any note, but with enough energy to blast the Askøy ferry backwards.’

‘So you do remember that time?’

‘When his drum kit was left on the quayside, you mean?’

‘And Arild was jumping up and down on the bridge like a yo-yo and got the skipper to turn back.’ At this his face lit up. ‘Those were the days, eh, Varg? Oh, those were the days.’

‘He bounced up and down behind the drums like a rubber ball, chipmunk cheeks, wild hair, as nutty as a fruitcake. When I see them in my mind’s eye – all of you, that is, the way you were then – it’s almost impossible for me to imagine you as old.’ I looked at him and his bearded face. ‘You, for example, are quite simply a completely different person.’

‘They didn’t live to be very old, either,’ Jakob said quickly, and his face darkened again.

‘What do you mean? Who?’

‘Both of them. Don’t you read death notices?’

‘Yes, I do, but I didn’t see anything…?’29

‘Less than a year between them.’ He flicked his fingers, without managing to make them snap. ‘And, just like that, they’re gone. Both of them.’

‘What did they die of?’

He craned his head and looked around. ‘I … don’t want to talk about it.’ He turned back to me. ‘Shall we go?’

‘Why won’t…?’

‘No.’

I nodded. ‘OK.’

Paul Finckel was still going strong. His chubby fingers were fidgeting with the side-seam of the dress belonging to the lady with the angst-ridden face, as though he were one of her nightmares brought to life. She, however, seemed oblivious as she hung around his neck grasping her own wrist.

We winked as we left.

He winked back and made some ape-like thrusts with his hips. The lady blinked and abruptly stared up at the ceiling as though someone had run a cold object down her spine.

Jakob and I supported each other down the dangerous staircase, past the surly bouncer and into the black December night.

I looked at my watch as we stepped onto the pavement. There were still a few hours left until midnight. It was a long time to the following day. Tomorrow was a foreign country. And I didn’t even remember if I had my passport on me.

4

The night sky was dotted with star-shaped crystals. They fell to earth like fluffy scraps of felt, melted and disappeared beneath our feet. We crossed Ole Bulls plass, which was closed to all through traffic. In the middle of the square there was a police vehicle with its engine running. On the opposite side some dark shadows crept alongside the walls. Somewhere in the distance a car horn blared, and from the other side of Byparken came the voice of a rejected suitor: ‘Oh, oh, oh, oh, oooh, lonesome me-e…’

Bergen surrounded Lille Lundgård lake and was reflected in its black water, the centre of which had acquired a film of grey ice. Along the western side was Bergen Art Gallery – containing the Stenersen collection – with its modernist façade, which adjoined the functionalist Kunstforening building – with Rasmus Meyer’s elegant collection of art and historical furniture – and there was also Bergen Electricity Board’s resplendent, Soviet-inspired homage to technology and progress. On the southern side was the library, like an authoritative mother keeping an eye on everything, and along the eastern side was one of the town’s oldest residential districts – the charming rooftop profile of Marken’s small higgledy-piggledy houses epitomised original Bergen, while Sparebank’s Steven Spielberg-style architecture testified to the 1980s capricious economic conditions, and the towering town hall block to local politicians’ abiding impotence: as out of place as a monument to Wagner at the Troldhaugen home of Edvard Grieg.31

We followed the footpaths around the lake, where the spring’s first sports event took place every year in wind and hail, and around which all the young families have trudged every 17th May, fleeing the Independence Day celebrations’ hot dogs, half-melted ice creams, uninflatable balloons and cardboard horns that burst your eardrums, in search of distractions such as traditional small-dinghy sailing among the ducks and seagulls in the muddy water.

Now there were neither balloon vendors nor hot-dog customers anywhere in sight. Some distance away, under some bare trees stood a group of down-and-outs sharing a bottle, which was passed from hand to hand and mouth to mouth. We didn’t feel a lot better ourselves as we staggered along.

I said to Jakob: ‘Over there, on that wall, I walked – or rather teetered – with a girl from upper secondary, pretending we were in Paris and strolling alongside the Seine.’

He looked at me sceptically. ‘You must’ve had a vivid imagination.’

‘It was spring.’

‘Did you ever get there? To Paris, I mean.’

‘I did. The following summer. But not with her.’

‘Not with her,’ he repeated. He was descending into a bout of depression. I could see it in his eyes. ‘I also remember you standing somewhere by a lake, Varg, and it wasn’t the bloody Seine you were dreaming about.’

‘Oh, yeah? Where?’

‘In Nygård Park. Some girl had dumped you …’

‘That’s novel.’

‘And you were staring into the water, and for a moment I thought you were going to bloody jump.’

‘Weren’t there any other girls then? Ones that hadn’t dumped us, I mean. Yet?’32

‘Yes, there were.’

‘You see. And? Great act, don’t you think? That way you had a chance.’

He shook his head. ‘If you think so.’ Then he turned abruptly to me, grabbed my lapels and stared straight into my eyes. ‘So why did she leave me, then?’

‘She? Who?’

‘You know very well who I mean, Varg.’

‘Your … wife?’

‘YES!’ He shoved me away and stood staring darkly across the water. ‘My … wife.’

A duck was quacking in the lake. Perhaps it wanted to express its sympathy. Or perhaps it was telling us to keep quiet so that it could get some shut-eye.

We walked on in silence. One circuit. Two.

We breathed in as deeply as we could, mixing the alcohol in our blood with oxygen, gradually getting our circulation going, in our legs and brains.

During the second circuit we began to talk again and after the third we felt clear-headed enough to dive into another Bergen Friday night.

‘If we do another circuit, we’ll have done the round-the-lake race,’ I said.

So we did, and felt even more refreshed and ready to face Johnny Solheim, Nordnesveien’s answer to Elvis, the local perpetuum mobile of the rock ‘n’ roll age: the eternity machine who never stopped singing his past hits.

‘One for the money,’ Jakob said.

‘Two for the show,’ I chimed in.

‘Three to get ready.’

‘Now go, cat, go.’33

And we shuffled off in the direction the blue suede shoes we no longer wore took us.

5

The performance was in full flow when we arrived. The dance floor was packed, and we struggled to force our way along the wall to a tiny table squeezed between a pillar and a swing door to the kitchen. Waiters came and went like the figures you shoot at in fun fairs. Perhaps we should have taken an air rifle with us.

The interior was fitted out in brown teak, with potted palm trees, burgundy, brothel-style furniture fabrics and a general air of poor taste. The room was filled with smoke, as if a volcano had erupted, and if that was not enough, smoke machines were spewing a thick fog across the stage, where a lurid smoke and light show and four background musicians framed the female vocalist, who constituted a magnetic field of her own.

I almost dislocated my neck trying to keep her in sight as we found the way to our small table. ‘I thought you said this was supposed to be an oldies’ show,’ I shouted over to Jakob, who was leading the way.

‘No, no, no,’ he shouted back. ‘Never on Fridays. Johnny’ll have his own “blast from the past” spot. They choose a seasoned performer every Friday. The younger singers do the main show. But the musicians are the same.’

‘You can’t even see them – not without a fog lamp.’

We pulled in our stomachs and wedged ourselves in, either side of the table.

The young vocalist was electrifying. She moved as though she were balancing on the edge of a non-stop orgasm and she 35handled the mike in a way that made Tina Turner seem like a girl guide. Her lips were full and moist and the round microphone head was almost in her mouth. Her tousled blonde hair was wet with gel and her face was round and robust in a girlish way. She was wearing a loose-fitting, black leather jacket and tight, black leather trousers, so tight you felt you might have been able to see what she had for lunch. Under the jacket she wore a grey T-shirt that was already soaked in sweat.

‘Who’s that?’ I asked, and could hear my voice jar.

‘Bella Bruflåt, a new rising star. I’ve heard rumours she’s already made a demo for her first LP.’

‘I can imagine. Except that on an LP you miss all this.’ I nodded to the stage where Bella had tellingly placed her left hand against the inside of one black leather thigh – her hand looked almost indecently white – while thrusting the mike back and forth to her mouth in even more unambiguous movements than before and emitting a primal scream, all underpinned by a piercing riff on the guitar, which caused a sensual groan to run through the whole crowd. For a few seconds the room was totally silent. The music had died, no one was eating or drinking, everyone just sat gaping with whatever orifices they possessed.

Then Bella laughed with pleasure, a rasping, provocative gurgle, and tossed her head as the applause rippled over her. She turned her back on us and stepped into the fog. And stopped. The spotlights fell onto her back, bottom and thighs. Electricity began to build in the room; the tension was at breaking point.

Slowly she began to wiggle her backside, in time to the drummer’s first, cautious whisks of the brushes. Then the bass came in: a slow, sensual beat. One dissonant, quivering note from a guitar cut through everything and was gone as Bella ground her hips in a slowly increasing rhythm.36

Jakob muttered beside me: ‘This is what I’ve always said. Religion is rhythm. Rise up and shout hallelujah, and the cry will spread through the audience without—’

He broke off and swallowed because Bella had placed one hand on her shoulder and was beginning to peel off her jacket. It slid down her bare upper arms as if she were skinning a slaughtered animal, while all the instruments converged on a single rhythm – a tap dripping through our veins from a distant kitchen.

Now her jacket was hanging loosely from one shoulder. With slow, studied movements she shifted the mike from one hand to the other and raised it to her mouth. Through the sound of the instruments you could hear a slow, crystal-clear human voice. No words, only a long, vibrating tone, a ray of golden sunshine breaking into a pitch-black room.

Then everything happened in a few short seconds. Her jacket fell to the floor. She turned round abruptly, arms in the air, and might just as well have been naked, so tight was the grey T-shirt against her body. The mike glittered between her fingers. The music rose to a rousing crescendo. In a split-second she lowered the mike again and began to sing, thrusting her crotch in rhythm: ‘Meet me in the middle of the night – Baby – Meet me when the moon has gone away – Baby…’

And we didn’t say no, not one of us. We would meet her there, all of us, in the middle of the night, when even the moon had gone to bed. And it would be just us and Bella and we would wake the dawn with our cries, we would make the dead rise and dance and the living turn to ashes around us.