6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: No Exit Press

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

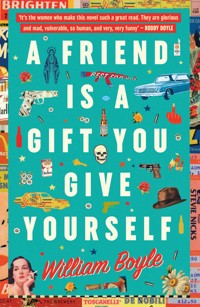

THELMA AND LOUISE MEETS GOODFELLAS when an unlikely trio of women in New York find themselves banding together to escape the clutches of violent figures from their pasts. After Brooklyn mob widow Rena Ruggiero hits her eighty-year-old neighbour Enzio on the head with an ashtray when he makes an unwanted move on her, she steals his vintage Chevy Impala and retreats to the Bronx home of her estranged daughter, Adrienne, and her granddaughter, Lucia, only to be turned away at the door. Their neighbour, Lacey 'Wolfie' Wolfstein, a one-time Golden Age porn star and retired Florida Suncoast grifter, takes Rena in and befriends her. When Lucia discovers that Adrienne is planning to hit the road with her ex-boyfriend, she figures Rena is her only way out of a life on the run with a mother she can't stand. The stage is set for an explosion that will propel Rena, Wolfie, and Lucia down a strange path, each woman running from their demons, no matter what the cost. A Friend is a Gift You Give Yourself is a screwball noir about finding friendship and family where you least expect it, in which William Boyle again draws readers into the familiar - and sometimes frightening - world in the shadows at the edges of New York's neighbourhoods.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Praise for WILLIAM BOYLE

‘The Lonely Witness is a map of Brooklyn’s genome. Amy Falconetti is that rarest of noir characters, a woman redeemed and a redeemer. Walking in her shoes for only a few blocks is worth the price of admission’ – Reed Farrel Coleman, author of What You Break

‘An excellent sequel with a superb plot, matched by its realistically shaped characters’ – Washington Post

‘Powered by brilliantly realized characters, a richly described and grittily realistic backdrop, and subtle yet powerful imagery, this is crime fiction at its best: immersive, intense, and darkly illuminating’ – Publishers Weekly

‘Deploying an inimitable tone that packs sardonic storytelling atop action and adventure, with a side of character development, Boyle’s voice works even when it feels like it shouldn't. It's just the right kind of too much’ - Kirkus Reviews

‘Boyle’s writing is raw, poetic, unflinching, nostalgic, andperverse. Urgency inhabits his pages, and the characters liveon weeks after you put the book down. Gravesend is a novelread in a day, and then again, slowly’ – LA Review of Books

‘Like all the best crime writers, Boyle is both a masterful storyteller and a powerful stylist… He has a sense of humour and a sense of place. Most of all, though, he has the true novelist’s true feeling for his characters’ – Alex Andriesse,North Dakota Quarterly

‘William Boyle has created intensely tangible characters, their voices, thoughts and feelings almost become physical, touchable, and are so very, very believable’ – Liz Robinson,LoveReading

‘Gravesend is a taut exploration of the ways we hurt and save (or try to save) one another. With unforgettable characters, a fist for a plot, and a deeply evocative setting, Boyle navigates alleys and streets with the best of them, Lehane, Price, and Pelecanos’ – Tom Franklin, bestselling author of CrookedLetter, Crooked Letter

‘William Boyle has created intensely tangible characters, their voices, thoughts and feelings almost become physical, touchable, and are so very, very believable’ – Liz Robinson,LoveReading

‘Gravesend is a book that hits you in the guts the same way David Goodis or Charles Willeford’s books do. Boyle’s mining that dark edge of America where no one is safe, not even from themselves. A dark ride but a seriously great ride’ – Willy Vlautin, author of The Motel Life,Northline, Lean on Pete, The Free, and Don’t Skip Out on Me

‘What makes William Boyle’s work ring with such a strong and true voice is that he realizes for many daily life is a struggle. His writing prays for them’ – Mystery People

‘Boyle creates an atmosphere of almost claustrophobic intensity’ – Crime Review

‘A “thread” of suspense doesn’t begin to describe the tension William Boyle has created in his novel The Lonely Witness. Amy is one of those refreshingly complex characters we see more and more of in today’s novels’ – Inside Jersey Magazine

‘There’s a natural, forthright style here that seems born of this writer’s sense of duty to his characters, these denizens of non-hipster Brooklyn living out the dooms they were born to, nurturing their vices, the hours of their lives plaited masterfully together, their lusts and regrets interlaced. The novel unspools without hurry but also without an extra line, giving neither the desire nor opportunity to look up from it. There’s an exhilaration that accompanies seeing a place and its folks this clearly and fairly, feeling at once that the writer is nowhere to be found and also working tirelessly to show you the right things. Boyle arrives in thorough possession of his seedy yet venerable world, this low-roofed urban hinterland. I can’t remember being more convinced by the people in a novel. Boyle’s characters, each in his or her own way, are accepting the likely future – with violence, with sex, with resignation, with rebellion, by being upbeat. You’ll be grateful, and it won’t take long, to be in this writer’s hands’ – John Brandon, author of Arkansas, CitrusCounty, A Million Heavens, and Further Joy

This book is dedicated to the memory of my grandparents, Joseph and Rosemary Giannini, who – I hope – would’ve gotten a kick out of it.

For the libraries and video stores where I spent my childhood.

Remember, no matter what, it’s better to be a live dog than a dead lion.

– Motel philosopher in Jonathan Demme’s Something Wild

screenplay by E. Max Frye

Let the people know I am not dead.

– Lisa De Leeuw, in an interview with Richard Pacheco

We walked around looking for ghosts.

– Conor McPherson, The Good Thief

Dear Wolfie,

You hanging in there? House good? How’s the Bronx treating you?

Monroe is a piece of shit right now. I need cigarettes. I usually keep a carton in the freezer, but I forgot to stock up, and I don’t feel like going out. My mother’s on the ropes. Eighty-nine yesterday and she can barely see or hear. We celebrated her birthday with some Hostess cupcakes I bought at the gas station up the street. She tells me about all the dead people who come over for parties that don’t exist. Freaks me out.

She sees these little kids. Says they’re sleeping on the couch. Says they won’t eat. She cooks for them. ‘Cooks’ is a strong word. She makes them butter sandwiches, mayonnaise sandwiches. The other day, I go out to ShopRite for two fucking minutes, I come home, and she’s buttered all these pieces of paper and left them around the house. Just regular pieces of paper, no sliced bread, and she’s slathered all this margarine on there, saying, ‘The kids must be hungry.’

I tried going to church, you believe that shit? You picture me in church? I got worried, thinking I take Communion, the fucking host goes up in flames in my hand and the priest gets one of those crazy, I’m-in-the-presence-of-a-demon faces. I don’t know why I went. My mother, she has these moments of clarity, and they’re always about church. Usually this biddy brings her Communion in the morning once a week, but I got the notion church might be a break. A snooze, that’s all it was. Found myself thinking of that girl-on-girl scene we did in that deconsecrated church in the Valley. I was a nun, you were a Jayne Mansfield knockoff. I’m looking at this stained-glass Jesus behind the altar, thinking of that. What a fucking life.

You know what I found the other day? A stack of your pictures in a green envelope full of tic-tac-toe games we must’ve played one bored afternoon. Not L.A. stuff. Your marks down in Florida, that’s what the pictures are of. Like four or five of that one, Bobby. He was a sad case, and I almost feel sorry for him. He looks like someone drowned a sack of his beloved rabbits in all these pictures.

I also found my Stevie Nicks stub from the White Winged Dove Tour. Best night of our lives. If I had the opportunity to live one day over and over – like that movie Groundhog Day – it’d be that one. Everything was perfect. Me and you getting lunch at Rhonda’s, our nails done after, hair done, drinks at Frolic Room, the show, later in Mac’s limo with the champagne. And I’ll tell you what: I really remember the stars that night. I close my eyes, I can still see the sky I was looking up at through Mac’s moonroof. Magic forever.

Come visit me, huh?

Best bad love,

Mo

Rena

Bensonhurst, Brooklyn

Sunday, June 11, 2006

After Sunday morning Mass and her regular coffee date with her friend Jeanne at McDonald’s, Rena Ruggiero is back on her block, Bay Thirty-Fifth Street. So strange to be from a block, to feel at home on only your block while all the others, even the ones directly surrounding you, feel so foreign. Her whole life spent on this block. Growing up in the house, staying through her time at Brooklyn College, and then moving into the upstairs apartment with Vic when they got married. And when her parents died, taking over the whole place. It was big for three people. Even bigger for one. Sixty-eight years the house has been in her family, bought eight years before she was born.

She stands out front now, as she often does, and considers the house’s flaws. It needs new siding. That was a project Vic had been in the process of setting up before he was killed. Probably needs a new roof, too. The porch sags. Posts and railings need to be scraped and painted, a lot of the wood rotten. The windows are old. Too much cold seeps in. She could sell it – the Chinese are buying up houses in the neighborhood like crazy – but selling seems like such a hassle.

And the stoop. She still sees Vic slumped there, as he was on that awful day nine years before. She remembers the exact way the blood pooled on the steps. She looks hard enough, she can still see spots where it has browned the cement forever. Poor Vic. Probably watching the pigeons on the roof of the apartment building across the street, Zippo the landlord guiding his kit in formation with a big black flag. And then Little Sal approaching with his gun raised.

Rena had been inside at the stove, frying veal cutlets. She heard the shot, figured it for a car backfiring, maybe some dumb kids with an M-80. She didn’t come out until she heard screaming and sirens and tires screeching. Walking out of the kitchen, down the hallway, the way she remembers it, was all in slo-mo. She wasn’t thinking something had happened to Vic. He was just sitting there; he wasn’t off at work. The fear had always lingered in her, but it wasn’t there just then. They had a ballgame to listen to, cutlets to eat. Little Sal was long gone when she made it to Vic.

Rena remembers how she crouched over him in the ambulance on the way to the hospital, crying, holding her rosary. Vic, who was in a bad business but had a soft voice and thoughtful brown eyes. His associates called him Gentle Vic. He’d raked it in for the Brancaccios. A huge earner. What had gone wrong had nothing to do with his work, just a beef with a punk, a kid named Little Sal trying to make a name for himself by knocking off a made guy. Shot Vic as he sipped on espresso, squash flowers from Francesca up the block in a ziplock bag on the step next to him.

Everyone knows about Vic, what he did, how he died, but no one talks to her about it in specifics. No one asks her what it’s like to see your husband bleeding to death. Or what it’s like to hose dried blood off your front stoop after burying the only man you’ve ever loved. The Brancaccios took care of her after the fact, paid for the funeral, gave her some money, but no one comes around anymore. She was never very tight with any of the other wives.

Rena goes inside and turns off the alarm. The alarm was Vic’s idea, after some break-ins on the block back in the early nineties. He was gone a lot and wanted her to feel safe. She takes off her coat and puts on water for tea and then decides she doesn’t want tea and shuts the burner. The phone is right next to the stove, an old yellow rotary mounted to the wall. A picture of her parents is encased in the plastic center of the dial. They’re smiling. It’s their thirtieth-anniversary dinner. They’re younger in the picture than she is now.

Her friend Jeanne had to go and bring up Adrienne over coffee at McDonald’s. Adrienne is Rena’s daughter, who lives over in the Bronx. Rena hasn’t seen her since Vic’s funeral. Hasn’t seen her granddaughter, Lucia, either. Lucia’s fifteen now; she was six the last time Rena held her, in tears, standing in front of Vic’s casket.

Rena wasn’t happy when she found out – in the middle of everything else – all the details about Adrienne and Richie Schiavano, Vic’s right-hand man, and she let it be known. Turned out they’d been an on-again, off-again thing since Adrienne was in high school. A kid, that’s what Adrienne was when they started up. This all came out at the funeral. Rena was floored by the news. She couldn’t believe it had gone on behind her back, behind Vic’s back. She couldn’t believe that Richie would disrespect their family like that. She couldn’t believe that Adrienne was such a puttana. Sure, she had bigger things to worry about, but she channeled much of her anger toward Adrienne. A natural reaction. Still, Adrienne holds this grudge against her for speaking up about the relationship with Richie. Rena was just concerned with the order of things, that’s all, what’s right and not right in the eyes of God and everyone. She remains concerned.

But it goes back longer than that, too. Adrienne was always either embarrassed by her mother or hating her for something. Not right. Rena’s more than a little sick in her heart over all of it, especially Lucia being caught in the crosshairs. High school age now and she doesn’t even have a relationship with her grandma. Shame.

Rena picks up the phone and dials Adrienne. She’s written hundreds of letters over the years, tried calling thousands of times.

One ring. Adrienne picks up. Rena hasn’t heard her voice since the last time she tried calling a couple of months back. ‘Yeah?’ Adrienne says, sounding sleepy.

‘Adrienne? It’s Mommy.’

Click. Adrienne slamming the phone down without hesitation.

Rena hangs up and just stands there. She takes a few deep breaths. She’d prefer not to cry. She thinks about a horrible article from the Daily News she read the day before, about a man hacked to death with a machete on the D train. A machete. Thinking about it keeps the tears back. What kind of person thinks this way?

The doorbell rings. She wonders who it could be on a Sunday. Or any day, really. Maybe those Watchtower people. Or a real estate agent trying to get her to sell the house again. Sundays don’t really matter anymore. Not what they used to be. Like everything else.

She goes into the hallway and sees a bulky figure through the tattered curtain on the window in the door. ‘Who’s there?’ she calls out, refusing to get too close.

Sound of throat-clearing. A man. ‘It’s Enzio!’

She moves closer and pushes back the curtain to look outside. Her neighbor Enzio is standing there wearing a Members Only jacket, his hair slicked back, blowing his big nose with a white handkerchief. He’s holding flowers in his free hand – daisies, her favorite. This is no coincidence. Over coffee, Jeanne had been hounding her to get a boyfriend again, saying she was only sixty and far from dead. All the eligible bachelors in the neighborhood had come up. Enzio from the corner was one. Eighty, if he’s a day. He washes his beautiful old car with no shirt on in his driveway. He wears his shorts high, the button often undone over his belly. He calls her baby and honey and dollface when she passes his house. He’s got the skeeviest smile.

‘It’s Enzio,’ he says again, softer this time. He tucks his handkerchief into his pocket.

‘What do you want?’ Rena asks.

‘Just to talk.’

‘What’s with the flowers?’

‘Come on, open up, huh?’

She hesitates but makes a move toward the lock. She’s what, gonna be afraid of a sad old man like Enzio? All he does is wash that car and read the racing forms in a booth at Mamma Mia across the street. A widower. But a different kind of widower. His wife, Maria, is fifteen years gone. Long as Rena knew her, Maria was a shut-in, wore a housedress and watched TV all day, doped on meds. Whatever the problem was, Rena was pretty sure it was made up. The whole neighborhood knew that Enzio ran around on Maria. Could’ve been that Vic had a goomar or two over the years, but he kept it quiet if he did, showed Rena respect. Still, everyone forgave Enzio his indiscretions. A wife like that, gone in the head, someone who’d totally cashed in her chips – well, a man needed a little excitement. Rena had always heard the gossip and didn’t give it much thought. Disgraceful on his part, sure, but a wife had certain duties.

Enzio had a few out-in-the-open girlfriends over the years. Jody from the bank was one. Jody wasn’t her real name. She was Russian. Pretty. It didn’t last. Enzio was loaded but cheap. Jody found a guy who took her to Atlantic City every weekend and wasn’t afraid to spend. Now Enzio is after Rena. The world in all its strangeness. She pulls the door open.

Enzio pushes the flowers at her. ‘Daisies,’ he says. ‘Your favorite.’

She accepts them, but instead of hugging them to her chest, she lets them dangle from her closed fist. ‘You know that how?’

‘A little angel told me, dollface.’ He smiles his terrible smile. She feels like she’s never seen it this close before. His teeth are glommed up with food. His lips wormy. He’s missed spots shaving around his mouth.

‘Jeanne’s a pain in my ass sometimes.’

‘Your friend has your best interests in mind. She knows I’m a good guy, a good catch. All these years, we’re dancing around each other, and now here we are. Vic gone, Maria gone. Last two standing.’ He puts out his hands. ‘Don’t get me wrong. I respect Vic. Respected him. Everyone did. “God bless Vic Ruggiero,” I always said. Gentle Vic. Hero of the neighborhood. Can I come in or what?’

She steps aside and waves him in. ‘Come on, I guess.’

He walks into the kitchen and takes off his jacket and folds it over a kitchen chair. They stand across from each other.

‘You know me a long time,’ Enzio says. ‘You know I’m nice. You know I’ll treat you nice.’

‘I bet you treated all the girls you ran around on Maria with real nice.’

‘Past is past, you know? The way I behaved was in direct correlation to Maria forsaking her wifely duties. The marital bed was cold. Ice-cold. And a man gets heated up. Besides, who we kidding over here? I got one foot in the grave. I’m trying to find someone for company. A nice dinner at Vincenzo’s. Maybe a movie.’ He pauses, looks around. ‘You gonna offer me anything?’

‘What do you want?’

‘Coffee? Maybe a cookie.’

‘I’ve got instant coffee and Entenmann’s.’

‘That’s no way to live.’

‘It’s not how I live. It’s what I happen to have right now.’

Enzio puts up his hands. Always with the hands up. ‘Okay, okay. Take it easy. Come over to my place. I’ve got good espresso and cookies from Villabate.’

Rena finds a pitcher in a cabinet over the sink, fills it with water, and puts in the flowers. ‘Thanks,’ she says. ‘For these, I mean.’

‘See, I’m a nice guy. I’m not scared to buy flowers.’

‘They’re pretty.’

‘See.’ He moves closer. ‘Come over to my place for coffee. I don’t bite.’

Rena touches the flowers and wonders where he got them. Probably the florist up on the corner. Vic always bought her daisies there after they fought. She wonders if Enzio ever saw Vic coming up the block with the flowers. Enzio and Vic rarely talked. Vic wasn’t the chatty type, and Enzio knew better than to try to get deep. When they did talk out by the fence, Enzio passing on his way home from Eighty-Sixth Street, it was about garbage pick-up or someone parking illegally in a driveway or the Yankees. Strange how you could live on the same block as someone forever and barely know him beyond small encounters and through-the-grapevine gossip.

‘I don’t drink espresso,’ Rena says, forever remembering it as Vic’s last drink. ‘It makes my heart race.’

‘A little won’t kill you. Have an adventure.’

‘Drinking espresso’s an adventure?’

‘I have wine. Maybe we can share a little wine. Homemade. From Larry around the corner. You know Larry? Nino and Rose’s son. He makes the good stuff.’

‘I don’t drink wine.’

‘At all?’

‘Not really. I used to have a glass at dinner when Vic and I would go to Atlantic City.’

‘Pretend you’re in Atlantic City. Loosen up a little. Nothing better than a blast of good homemade wine.’

Rena sits down at the table and puts her head in her hands.

‘I upset you?’ Enzio says.

‘I don’t know,’ Rena says.

‘You don’t know if I upset you?’

‘That’s what I said.’

‘If I said something wrong, I didn’t mean to –’

‘It’s okay.’

He comes over and rubs her shoulders.

‘Please stop,’ she says.

‘It’s no good?’ he says.

‘I don’t like it. I don’t like being touched.’

‘At all?’

‘No’s no, okay?’

He takes his hands off her and lets out a big, gusty sigh.

Rena tenses up.

‘You’re a tough nut,’ he says. ‘You don’t want any companionship? I’m just trying to be a nice guy here.’

‘Okay, okay,’ Rena says.

‘Okay? What’s okay got to do with it? I’m lonely. You’re not lonely? We could be lonely together. Watch a movie. Drink some wine. Eat some cookies.’

‘Enough with the wine and cookies.’

‘A goddamn tough nut.’ He sits down across from her. ‘You want me to leave?’

‘I don’t care what you do.’

‘I’m not leaving unless you come with me, how’s that?’ He laces his fingers together and cracks his knuckles. It’s loud, a tiny thundering, like stepping on Bubble Wrap. ‘Maybe I’ll tell you a story? That’s what I’ll do. You know Eddie Giangrande? He was involved in that Fulton Market heist back in the seventies. He lives over on Twenty-Fifth Avenue. You know him, right? Sure you do. His wife’s Madeleine. Vic must’ve crossed paths with him.

‘Eddie, he’s a big guy. Two-eighty, two-ninety. And he’s a happy-go-lucky sort. Every time you see him, huge smile from here to here. Molars showing. Sure, why not? He made out big time with that heist. Never got collared either. Don’t ask about the details, by the way. I know – I know a lot – but I’m sworn to secrecy.’ He mimes locking his mouth and throwing away the key. ‘Still, Eddie – with all he’s got, I mean, what more’s he want, right? – gets in with these Russians. The Godorsky brothers. They cross him; he crosses them. Again, the details aren’t important. The short of it is he winds up out at Dead Horse Bay with a gun to the back of his head, the Godorsky brothers telling him to make his peace with God. Don’t repeat this story, by the way. This is for your ears only. I know you have experience keeping quiet with sensitive information.’

Rena nods. ‘I won’t tell anyone.’

Enzio continues: ‘Good, thanks. So, Eddie, he thinks about Madeleine, he thinks about his kids, he thinks maybe he’s gonna piss himself and then his brains’ll be splattered on the beach, the end. But instead of pissing himself or begging for his life, he starts laughing. Like a goddamn clown. Just hardy-fucking-har. Excuse me. Just hardy-har-har, you know? Maniac stuff. The Godorskys are taken aback. They’ve never seen this. Eddie laughs harder. The Godorskys start arguing in Russian. They think maybe he’s got something on them they don’t know about. They turn on each other. Gun’s off the back of Eddie’s head. Now the one brother is pointing the gun at the other brother. The other brother takes out a gun and points it at the one with original gun. Then bam. They shoot each other. Just like that. Eddie gets up and looks around and the Godorskys are on their backs, choking on blood. Eddie laughs some more and then steals their car and goes home.’

‘What’s the point of that story?’ Rena asks.

‘Laugh a little, that’s what.’

And she does laugh. Russian mobsters shooting each other like that. Jesus, Mary, and Saint Joseph. What a tale.

‘There you go,’ Enzio says. ‘You’ve got a nice laugh. All these years, I’ve never heard you laugh, you know that?’

She’s still laughing. Now she can’t stop. She’s looking across at Enzio, this old man who just told this ridiculous story, and she’s noticing his elbows on the table, his flabby chin, hair under his nose and around his ears that he’s also missed shaving, earlobes that dangle like melted coins, a little burst of blood vessels on his forehead.

‘Okay, okay,’ Enzio says.

‘I’m sorry,’ she says, trying to catch her breath. ‘I can’t stop. I’m gonna pee my pants.’

‘Don’t piss your pants.’

‘I can’t –’

‘Christ, what’s so funny?’

She gasps. Tries to settle herself. Her laughter finally sputters to a stop. ‘Sorry. Just the whole thing.’ She waves her hands in front of her as if swatting away gnats. ‘I’m done, I swear.’

‘You’re laughing at me?’ Enzio asks.

‘Not at all,’ Rena says.

‘I’m no fool.’

‘I know. I mean, you wanted me to laugh, right?’

‘Not like that.’

She gets up. ‘I need some water. You want some water?’

‘I don’t like water.’

Rena goes over to the sink and runs the tap, passing her hand through the stream to make sure it’s cold enough. She takes a glass from the dish drain, fills it, and slurps down the water, her back to Enzio. ‘You’re mad?’ she asks. She doesn’t particularly care if he is – he’s just a neighbor to her anyway – but she feels bad for laughing at him. She feels bad he knows she was laughing at him. She wishes Vic was still alive for a lot of reasons, but mostly, right now, so she wouldn’t have to deal with Enzio.

‘I’m fine,’ he says, picking at his ear.

She runs more water into her glass and downs it. ‘I’ll come with you to your house,’ she says, and she’s not even sure why she says it. Maybe she knows it’s the only way the tension will die.

‘Yeah? Wine and cookies?’

‘One glass. Maybe a cookie.’

Enzio claps his hands together. ‘That’s a start.’

Rena places her glass in the sink slowly, hoping if she takes long enough Enzio will go away and she won’t have to go with him on this, this… what else to call it but a date?

‘You won’t be sorry,’ Enzio says, grabbing his jacket. ‘I’m a gentleman.’

‘Famous last words,’ Rena says.

* * *

Enzio’s house is just a few doors down, a two-family brick job. Enzio no longer rents out the downstairs. He tried about fifteen years ago and got into a bad situation with a bunch of gypsies. A Christmas wreath still hangs on the front door of the upstairs apartment, which is where he lives. An Italian flag dangles from a pole rigged on the ledge of a third-floor window. The flag is weather-bitten, ragged. The Virgin Mary in the front yard has a chipped nose. Next to her is a flattened garden that died with Maria. Enzio’s near-mint 1962 Chevy Impala, driven sparingly, is under a blue tarp in the driveway.

They climb the short staircase up to the second-floor entrance. Enzio leaves his white Filas on a mat outside and asks Rena to take off her shoes.

‘Really?’ she says.

‘I care about the carpets.’

She nudges her feet out of her white Keds and kicks them onto the mat next to Enzio’s sneakers. All these years, she’s never been in his house. Not once. Not for coffee with Maria. Not anything.

It’s exactly what she imagines. Totally from the past: green shag rug that’s still in decent shape, plastic on the sofa. Elaborate vases. Paintings of vineyards and posters of Jesus on the walls. There’s a heavy glass cigar ashtray on a coffee table covered in lace doilies and the smell of bad cologne in the air. The only thing out of place is the big-screen TV in the living room.

‘You like the TV?’ Enzio says, noticing her noticing it.

‘It’s big,’ she says.

‘Sixty inches. Picture’s great. Like having the movies in your house.’

‘I don’t get these big TVs. Give me a little TV. That’s fine. Why do I need to feel like I’m in a theater?’

‘I’ll show you the picture after. You’ll be impressed.’

Rena follows him into the kitchen. She takes a seat at the table. It’s Formica, the top patterned with white and gold boomerangs. A saltshaker stands alone in the middle of the table, a hulking ring of keys snaked around it. She looks over at the refrigerator. No pictures, no magnets. Dirty dishes are toppled in the sink. Empty pizza boxes are stacked on top of the dish drain.

Enzio motions at the boxes and says, ‘The bachelor’s life.’ He digs around under the sink and comes out with a dusty magnum of wine. He strips away the seal, humming, and uses a corkscrew key to yank the cork. He fills a couple of juice glasses, their flowered sides laced with smeary fingerprints, and gives one to her.

‘Thanks,’ Rena says, lifting the glass up to her nose and taking a whiff.

‘Larry does a great job with this,’ Enzio says. ‘He makes it down in his basement. I used to make it like that, but I got lazy. He’s devoted.’ He comes over and sits across from her at the table, reaching out to clink her glass. ‘Salute.’

Rena doesn’t clink back. She sips the wine. It’s fruity and heavy.

‘The good stuff, right?’ Enzio says.

‘Not bad,’ she says.

‘Not bad, my ass.’ He takes a long slug. ‘You want a cookie? What kind? Savoiardi? You’re a savoiardi girl, I can tell.’

‘I’m good.’

‘Come on, have a cookie.’ He gets up and opens the refrigerator. The white box of cookies is on the top shelf, wrapped carefully in a plastic Pastosa bag. Keeping cookies in the refrigerator was a big no-no for Vic.

‘I’m good.’

‘You sure? I’m having one.’ He peels back the plastic, opens the box, and takes out a seeded cookie. He munches on it, cupping his palm under his mouth to catch the crumbs. ‘I’m lonely eating this alone. Have one.’

‘I’d appreciate it if you’d quit with the cookies. I want one, you’ll be the first to know.’

‘To each his own.’ He turns and goes back into the living room. Starts fiddling around with the TV. The screen bleeps on. Bleeps? She’s not sure of the word for whatever TVs do now when they turn on. Not bleeps, exactly; more futuristic than that. A big bubble opens up in the middle and then little dreamy rainbow raindrops flood the blackness.

‘What are you doing?’ Rena says from the kitchen.

‘Enough with the slow dancing,’ Enzio says. ‘I’m putting something on for you.’

‘I’m gonna be impressed by your big TV?’

The screen is snow now.

And then it’s not.

And then there are bodies. Smooth bodies, tangled, two men and a woman. She’s blond and fake with silly boobs. The men are hairless, muscly in all the wrong ways, barbed-wire tattoos on their arms. Rena doesn’t want to think about what they’re doing, all of them involved like that.

‘What is this?’ she asks, standing up.

‘My favorite kind of movie.’

‘Uh-uh. Nope.’ She shakes her arms and puts up her hands, as if she’s just touched something skeevy, maybe a dead mouse in a trap. She keeps her eyes away from the screen, not wanting to catch another glimpse of the bodies. It’s the first time she’s ever seen pornography. Vic, if he ever whacked off, must’ve done it to old Life spreads of Sophia Loren, because Rena never found any dirty stuff in the house. Not even a Playboy.

‘You don’t like it?’ Enzio says.

‘No, I don’t like it, sicko. I’m leaving.’ She’s in the living room now, everything swirling, focused on making it to the front door without any unnecessary Enzio contact. It’s weird to be walking around his house in her socks.

‘Don’t leave. Let’s watch. You’ve lived your whole life like a prude; let it go.’

Rena stops. ‘You’re calling me a prude? You don’t know me.’

‘I know you.’ Enzio’s closer to her now, almost at arm’s reach. ‘Loosen up, huh?’

‘Fuck you, okay? You like that? You like me talking like that?’

Enzio puts up his hands. She can see the action on the screen behind his head. He says, ‘It’s a nice movie. Nothing too crazy. I’ve got the wine –’

‘Nice movie?’

‘It’s nothing strange.’

‘It’s strange to me, okay?’

‘I’ve got Viagra. We can have some fun.’

‘Excuse me?’

‘Viagra.’

‘You’re gonna take a Viagra and then we’re gonna what? Watch this movie and have sex?’

Enzio shrugs. ‘Make love, yeah. I can satisfy you.’

Rena’s not sure if she should laugh again or continue storming out. What those bodies are doing now! Like some horrible painting of hell. He’s really thinking she’s going to go along with this? Crawl onto the couch and let him go to town? ‘I don’t think so, Enzio,’ she says, so shocked that her voice feels full of restraint.

He moves toward her and puts his hand on her arm. ‘Think about it. You’re gonna go back to your quiet house? We’ve got entertainment here. We could have real fun.’

‘Get your hand off me, please.’

‘I got this Viagra,’ he says. He pulls his hand away from her arm, reaches into his pants pocket, and fishes out a small blue pill. He pops it into his mouth and swallows it dry. ‘Don’t you want to touch me? Don’t you want to be touched?’

‘I told you, I don’t like being touched.’

He’s getting closer again, reaching for her.

She sidesteps him and picks up the heavy glass ashtray from the coffee table, holding it up in front of her chest with both hands. ‘Touch me again, I’ll hit you with this.’

‘Rena.’

‘I’m serious.’

‘You’d hit me?’

And then he’s smiling and his hand is on her waist. She can feel how rough and warm it is through her shirt.

‘I’m about ready for some love,’ he says. ‘Aren’t you?’

She lifts the ashtray over her head and then thwacks him across the head with it, hard as she can. A raw-meat sound comes with the impact. And there’s a little spray of blood. He makes a noise, a small, prolonged one, like a balloon deflating. He spins and collapses toward the coffee table, his head slamming the edge on his way down. He crumples to the floor.

‘Jesus Christ,’ Rena says to no one. ‘I told him not to touch me.’

She drops the ashtray, blood mapping its bottom.

She looks at the ceiling. Closes her eyes.

Three, four minutes pass like that. A lifetime.

She squats next to Enzio. She looks closely at his back to see if he’s breathing. Like the first six months with Adrienne. Watching the rise and fall of her baby’s breathing. Paranoia and parenting so intertwined. But this is something different.

He’s still breathing, but it’s slow.

She thinks of a woman she saw on Bay Thirty-Fourth Street once. Just pushing her shopping cart along and then her feet went out from under her and she fell sideways, hitting her head against the sharp point of an old iron fence. Blood then, too. And slow, pained breaths.

The worst part is Enzio has wood from the Viagra. It’s tenting up his pants.

The shininess of the movie draws Rena’s attention back to the screen. Moans getting louder. Mechanical pounding. She watches to keep her eyes away from Enzio. She thinks maybe when she looks back at him next, he’ll be sitting up, knuckling the blood from his brow, ready to apologize.

What’s happening on the screen now mystifies her. They’re moving like the oily wrestlers Vic used to love to watch.

Back to Enzio. More blood, pooling around his head on the green shag rug. Clotting darkly. The thick threads pimpled red.

‘Jesus Christ,’ she says again.

She stands up and walks over to the TV and feels around on the side of it for a power button. She hits the volume controls first, and the noises from the movie get louder. She’s not shaking. She feels like she should be shaking. She punches a couple of other buttons and finally powers down the TV, the nightmarish final image – the woman on all fours over one man, while the other drills her from behind – sputtering away.

Oppressively quiet now. She swears she can hear the blood leaking from Enzio.

Calling 911 doesn’t occur to her.

She goes back to the kitchen and sits at the table. The wine Enzio poured for her is still there. As if it would be gone somehow. Dust specks float on the surface. She downs the rest and pushes the glass away. It’s close to the edge. She pauses, but then thinks, What the hell? and pushes it farther. The glass falls from the table and shatters on the kitchen floor, a mess of splintery shards. She gets lost staring at the boomerangs in the Formica. She thinks of her house, of this house, of this block, this neighborhood, and decides she should just leave.

She doesn’t have a car anymore. She sold Vic’s Chrysler Imperial after he died and hasn’t needed one. But Enzio’s keys are right there in front of her.

If Enzio’s not dead, he won’t come after her. He’ll be thinking she’s still connected through Vic. All she’s got to do is get on the horn. And it’s true. Tell Vic’s old crew this creep tried to rape her, he’ll probably wind up being dismembered and buried somewhere out in Jersey.

And if he’s dead – she’s not checking, no way – she didn’t mean to kill him. It was an accident. Hitting that table on the way down did the real damage. A man can’t just put his hands on a woman like that. Self-defense, pure and simple. If he hadn’t turned on that dirty movie and popped that pill and then touched her. What he said, to boot. She’s not sorry. He’s a dirty old man, but that’s no excuse.

Those keys.

She can just get in the Impala and drive to the Bronx. Drive to Adrienne and Lucia. Come to them out of desperation. They won’t be able to refuse her. Maybe something good can come of this.

* * *

Outside, the key glistens in her hand as she slips her shoes back on. It took some doing, sorting through the other keys on the ring, but the one for the Impala showed itself to her. She and Vic had an Impala back in the early days of their marriage – it was the car they drove to the Catskills for their honeymoon – and she recognized it immediately. A small key with a slot in it. Silver.

She pulls the tarp off the car, folds it as neatly as she can, and stuffs it in the garbage can chained to the front fence.

She wonders if anyone is watching her.

She looks up at the windows in the apartment building across the street. People move behind drawn shades, caught up in their own lives, as they should be. A bus on Bath Avenue wheezes to a stop. Some kids jump around outside the deli on the corner. Otherwise, Sunday quiet reigns.

No one is noticing her.

She stares at the car. It’s been a while since she’s seen it out from under the tarp. Crayon black and shiny. Rosary beads hanging from the rearview mirror.

Rena remembers how, on summer Saturdays, Enzio used to get in the car, start it up, back up to the edge of the driveway, and just sit there listening to WCBS for about thirty minutes while sunning the hood. Sometimes he’d check the oil and wipe the dipstick on a crusty rag he kept in his back pocket. He doesn’t do that anymore.

She opens the driver’s-side door and gets in behind the wheel. Red interior. The car smells like gas and grease and vinyl. She runs her hand over the dashboard, which Enzio cleans with expensive wet wipes that he buys at a crammed-to-the-gills automotive store on Benson Avenue. She adjusts the mirrors and starts the car. Shifting it into reverse, she lulls it out of the driveway, careful not to clip the nearby telephone pole.

At the end of the block, she turns left and heads for the Belt Parkway toward Long Island. From there, she knows she’ll get on the Cross Island Parkway and then take the Throgs Neck Bridge. The car has a glowing radio. She searches the stations and settles for Lite FM.

Wolfstein

Silver Beach, the Bronx

Wolfstein is sitting in her yard on the paint-chipped bench next to the birdbath, smoking her last Marlboro 100 and drinking a Bud Light. Her neighbor from down the street, Freddie Frawley, wearing Yankees gear from head to toe, walks by out in the street with his St Bernard. He waves at her.

‘Wave all you want, Freddie,’ Wolfstein says. ‘Just don’t let your dog shit in my yard again. The mound I cleaned up the other day, it was like a garden hose.’

‘That couldn’t have been Freddie,’ Freddie says.

‘Who names a dog after himself?’

‘Freddie Junior – what’s wrong with that?’

‘Watch he doesn’t shit in my yard again, okay?’

‘Look, he’s not shitting in your yard. You’re a witness.’

‘Now he’s not shitting in my yard. I go inside, who knows?’

Freddie heads away up Beech Place, shaking his head.

Wolfstein stares at her rosebushes. Looking good. She saw that kid from around the block, Billy Farrell, come onto her lawn and pick one for his little girlfriend the day before. She’s got a harelip, the girlfriend. Goes to Preston. Let Billy have it. Fucking romance, sure, she’ll sacrifice a rose for that.

Two years Wolfstein has been in Silver Beach. She likes it. They don’t know her history. No one asked, and it’s a long shot that anyone would ever guess she starred in skin flicks all those years ago. The house belongs to her friend Mo Phelan, so the co-op board doesn’t give her any shit. Mo’s upstate in Monroe with her sick mom. Anything’s upstate when you’re from the city, but it’s only really sixty miles. Ma’s stubborn, won’t leave her place up there. Otherwise, Mo might be down in the Bronx with Wolfstein. She sees Mo only every once in a while these days. Mo, who she owes everything to. Mo, who helped her navigate San Fernando Valley. Mo, who saved her when she was on the ropes in her late thirties. Mo, who set her up in Florida after Los Angeles spit her out. Mo, who was instrumental in creating the hustle that sustained her, that still sustains her.

Wolfstein grew up not too far away, in Riverdale. Silver Beach is different. Irish Riviera and all. Last name like hers, they give her that second look, but she mostly keeps to herself, and no one really bothers her.

Across the street, there’s yelling. That Adrienne giving it to her daughter again. Her voice like a garbage can being dragged across a sidewalk. Who knows what she’s yelling about? The poor daughter, Lucia, about fourteen or fifteen, comes storming out the front door and looks across at Wolfstein, open-mouthed.

Wolfstein tries to see herself through the girl’s eyes: red macramé top, her gold bra showing beneath it, sleek blue gym shorts from the eighties that still fit her, dyed brown hair. A weirdo. Some kind of messed-up queen, maybe. Not really an old lady, but old to a kid.

And Lucia, she’s a sorry sight in a tattered Guns N’ Roses T-shirt and denim cut-offs, red Chucks with socks that don’t match. She takes a lollipop out of her pocket, unwraps it, and jams it between her teeth.

Wolfstein motions for Lucia to come over.

The girl looks over her shoulder and then back at Wolfstein like, Me?

Wolfstein nods.

The girl looks behind her, as if to make sure her mom’s not watching, and then comes chugging over.

Wolfstein butts out her cigarette on the bench.

‘Hey, can I bum a cigarette?’ Lucia asks.

‘How old are you?’ Wolfstein says.

‘Fifteen.’

‘That’s a big no, kid. Sorry. Anyhow, that was my last. What are you and your old lady always at war about?’

Lucia shrugs.

‘She’s got a shrill-ass voice,’ Wolfstein says.

‘Tell me about it,’ Lucia says, clicking the lollipop around.

‘We’ve been neighbors a while now and we’ve never even talked. You know my name?’

‘Wolf-something?’

‘Wolfstein. What’s your mother say about me?’

Lucia hesitates.

‘Tell me.’

‘I don’t want to say what she said.’

‘Diplomatic. I get it. We had a little shitstorm about parking back when I first moved in, me and your old lady. I don’t even have a car, so I’m not sure why I got so hot. It was just the principle of it. Her boyfriend – your dad, maybe? – he was always blocking my driveway.’

‘That’s Richie,’ Lucia says.

‘Not your dad, then?’

‘I never met my dad.’

‘Tough break. But, honestly, dads are wild cards. Mine was a lazy ballchunk. Wasn’t there my whole childhood, but he came sniffing around in my twenties and thirties when I was raking in the big bucks.’ Wolfstein pauses. ‘You want to come into my joint for a drink?’

‘A beer?’

‘I’m not gonna give you a beer, no way. How about a ginger ale?’

‘I guess.’

Wolfstein stands up and works out the kink in her right leg. It’s been there for a while, this kink, a little locked-in tremble that pulses with pain. She runs her hands over her thigh, as if locating where it hurts.

Lucia watches her.

‘You like Guns N’ Roses?’ Wolfstein says, pointing at Lucia’s shirt.

‘I don’t know.’

‘You don’t know if you like Guns N’ Roses? What’s with the shirt?’

Lucia chomps down on her lollipop until it shatters in her mouth. She stuffs the paper stick in her pocket and crunches the candy. ‘It was Adrienne’s,’ she says.

‘You’re gonna have no teeth by the time you’re twenty,’ Wolfstein says.

‘I don’t care about my teeth,’ Lucia says.

‘You don’t care about your teeth?’

‘Why should I?’

‘You get teeth troubles, kid, watch your ass is all I’m saying. Everything bad starts with teeth troubles.’

Another shrug.

Wolfstein guides Lucia into the house through the side door and gets her settled on the orange counter stool in the kitchen. Lucia spins around, her legs flailing, torn between wanting to be a kid and not wanting to be a kid.

‘You fall and bust your head, that’s on me, so quit it, huh?’ Wolfstein says.

Lucia stops spinning and looks around: at the vintage dinette set, the buttercup yellow retro refrigerator, the dried roses hanging from the ceiling. And then she looks out into the living room. Sofa. Funky lamp. Hardwood floors. Looming wall mirror with gold scrollwork. Pictures on the wall – classy ones. Wolfstein and Hammie Fields at an awards banquet. A behind-the-scenes still with Crystal Desire, where they both have perms and are wearing silver robes. Sitting on a sun lounger in a red-striped one-piece in Malibu – a B-roll shot from a Leg Work spread that was way too tasteful to use. And her prized possession: a framed picture of when she and Mo met Stevie Nicks backstage at the Wilshire Ebell Theatre on the White Winged Dove Tour. What a time it was.

‘Your place is pretty cool,’ Lucia says.

‘It’s my friend Mo’s house,’ Wolfstein says. ‘I’ve taken it over the last couple of years, while Mo tends to her mom up in Monroe.’

‘What are those pictures from?’ Lucia asks.

‘My past life.’ Wolfstein opens the fridge and grabs the kid a pony bottle of ginger ale that she keeps around only as a mixer. She cracks another Bud Light for herself.

Lucia accepts the ginger ale and the cap twists off with a hiss. ‘What were you?’

‘In my past life?’

Lucia nods.

‘I was a goddess,’ Wolfstein says.

Lucia’s clearly not sure what to make of that. ‘That’s not here, is it?’

‘I lived in Los Angeles a long time.’

‘Were you in movies?’

‘I was.’

‘Awesome.’

‘I did some work I was proud of, but it wasn’t all fun.’ Wolfstein leans on the counter, gives Lucia the once-over. ‘You’re a scrawny kid, anybody ever tell you that? Your mother feed you anything over there?’

‘I eat a lot of popcorn and bagels and pizza. I like to eat.’

‘I once knew a girl called Hunny. H-U-N-N-Y. Sweetheart. But a terrible eater. I couldn’t get her to try anything green. A salad, even. I’d say to her, “Hunny, you need something green, you’re gonna croak.” She’d eat chips and drink Diet Cokes and that was about it. Pills, too, but you don’t need to know about that. One day, she up and dies. No kidding. I says to myself, “You see where not trying things gets you? Spread the word. Teach the children.”’

Lucia looks disinterested.

Wolfstein continues: ‘Eat healthier is what I’m saying. You hungry now? I made a salad. Chickpeas and arugula with a balsamic vinaigrette. Say the word.’

‘I should go.’ Lucia hops off the stool and somehow nearly falls on her face, hits the floor with her knees. Wolfstein was clumsy as a teen, too. She remembers a yard in Nyack, where her mother dumped her with her aunt as a kid. Must’ve been a friend’s yard, because they lived in a squalid apartment. She remembers a fall in this yard, a sweet, disastrous slamming to her knees. Bricks thickly scraping away the skin there. Blood. Burning. Just a dumb fall by a dumb girl. Pigtails. Teeth not yet fixed. Everyone calling her Woofstein. The girl whose yard it must’ve been hosing her down after the fall, saying, ‘Look at all that dumb girl blood.’

Lucia’s not hurt like that, but she stays on her knees. Wolfstein scurries over and helps her up. ‘Shit, I’m fine,’ Lucia says, brushing her away.

‘I’m sorry I made you feel bad about eating,’ Wolfstein says.

Lucia stands up and looks at the floor.

‘You come over whenever you want,’ Wolfstein says. ‘I’ll keep a few ginger ales around for you. Eventually, we get to be pals, you come of age, I’ll pass you a smoke.’