Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Notting Hill Editions

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Serie: Classic Collection

- Sprache: Englisch

Thackeray, author of the masterpiece Vanity Fair, was considered one of the finest writers of the Victorian heyday: Dickens was his closest rival. This anthology covers all of Thackeray's versatile genius: his sketches, journalism, essays, cartoons and fiction. With explanatory notes by Scholar and writer John Sutherland, this varied selection offers a lens into Victorian life by one of its most distinctive voices.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 158

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Notting Hill Editions is an independent British Publisher devoted to restoring the art of the essay. The company was founded by Tom Kremer, champion of innovation and the man responsible for popularising the Rubik’s Cube.

After a successful career in toy invention, Tom decided, at the age of eighty, to engage his life-long passion for the essay. In a digital world, where time is short and books are cheap, he judged the moment was right to launch a counter-culture. He founded Notting Hill Editions with a mission: to restore this largely neglected art as a cornerstone of literary culture, and to produce beautiful books that would not be thrown away.

The unique purpose of the essay is to try out ideas and see where they lead. Hailed as ‘the shape of things to come’, we aim to publish books that shift perspectives, prompt argument, make imaginative leaps, and reveal truth.

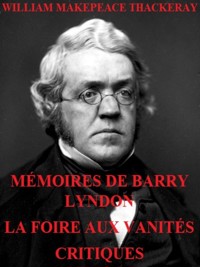

Samuel Laurence: Portrait of Thackeray in Middle Age

A ROUNDABOUT MANNER

Sketches of Life by W. M. Thackeray

–

introduced by John Sutherland

Contents

– ILLUSTRATIONS –

Samuel Laurence: Portrait of Thackeray in Middle Age

Thackeray, self-portrait, at the same period, going roundabout

Thackeray’s self-designed house on Palace Green

Thackeray’s daughters putting their puppets away

Thackeray’s ironic self-portrait in Vanity Fair

‘An Historical Study’

‘The Gallows’

Cover of first edition of The Little Snobs

Frontispiece of the volume edition of Vanity Fair

‘A Trifle from Titmarsh’

John Sutherland

– Introduction –

I was inducted into a lifetime love of Thackeray by a remarkable woman: Monica Jones, a lecturer at Leicester University, is known, nowadays as the paramour and muse of Philip Larkin.

Jones’s views on life and literature, which she studiously refrained from putting into print (most academic publication was, she believed, drivel) permeated the work of Britain’s most esteemed twentieth-century poet. They also had a formative effect on lesser me.

It was Miss Jones who directed me, tutorially, to Thackeray with the instruction: ‘He will be gold in your pocket for life.’ He could jingle there alongside her other two favourite authors, George Crabbe and Walter Scott.

I went on to do a doctoral thesis on Thackeray and a book on his uniquely relaxed working methods. Fuelled by my fascination with him, I later edited the three major novels: Vanity Fair, Pendennis, and Henry Esmond, digging into the dust that, alas, lies thicker on their author than it does on Dickens, the Brontës, George Eliot, or even the ‘lesser Thackeray’, Anthony Trollope.

My aim was simple – I wanted to get as close to the man as a century’s historical distance would allow. As part of that project I spent hours contemplating the Queen Anne House he designed and built for himself – 2 Palace Green, Kensington. It is now the Israeli embassy.

Thackeray’s house in Palace Green, Kensington

The house embodies in red bricks his Augustan view of life, but the hem of the robe for me was the manuscripts: one touches what his hand and pen touched. Thackeray’s literary remains are disjecta membra, torn into posthumous fragments and scattered in scores of repositories by nineteenth-century admirers and souvenir hunters. I felt, glamorously, like a scholar-adventurer hunting them down – an unusual feeling in academic life.

These literary remains, as their crests and occasional stains often testify, were written of an evening in one of his clubs (prominently the Garrick, Reform, and Athenaeum), the author creatively ‘warmed’ with wine (he loved the ‘cloop’ of the bottle’s opening and had a famously refined palate). The printer’s boy waited eagerly for the sheets next morning outside his house door. Unlike Dickens, whose script is tangled, Thackeray’s handwriting style was legible and slipped effortlessly into print.

That clubman easygoingness is the essence of Thackeray. It breathes over all his published work. He will never, like Austen, Dickens or Brontë, embellish a British banknote or postage stamp – but he has a fine memorial room at the Reform Club ornamented with a magnificent portrait of him by Samuel Laurence.

At the very end of his life he was advised by his doctors to exercise. In his diary he recorded his daily exertion as the number of steps he took (foreswearing the cab) from his house to the Athenaeum, where, doubtless, he undid his good pedestrian work with a hearty lunch. In his club, with fellow members of a like mind, Thackeray was free to converse. The Thackerayan voice itself, as recalled by friends, was metropolitan, a little high-pitched (he was not a good lecturer), occasionally man-among-men bawdy, always witty, and tinged with world-weary melancholy.

One sees Dickens, in what critics have called the ‘Dickens Theatre’. But one hears that unmistakable Thackerayan voice in everything Thackeray wrote. He converses with us. Take, for instance, the famous envoi to Vanity Fair:

Ah! Vanitas Vanitatum! Which of us is happy in this world? Which of us has his desire? or, having it, is satisfied? – Come, children, let us shut up the box and the puppets, for our play is played out.

The children are Thackeray’s daughters

Thackeray’s life was cut short but he left us millions of words. Over half of them are ‘casual’, occasional, journalistic – above all, essayistic. What was it Samuel Johnson called the essay? ‘A loose sally of the mind.’ That description, the unloosed sallying mind, fits Thackeray’s oeuvre perfectly.

—

Thackeray’s ‘stock’ was Yorkshire gentry – he had, his biographer Gordon N. Ray reminds us, the three generations behind him which make an English gentleman. As Ray also argues, Thackeray’s great endeavour in his writing was to redefine traditional English ideals of what it was to be a gentleman, historically the exclusive property of aristocracy and royalty – for the emergent middle classes of Victorian England. The new genus of gentleman could be noble, whether his blood were blue or not. The finest gentleman in Vanity Fair is William Dobbin, whose father was a greengrocer.

William Makepeace Thackeray was born in 1811 in India – a country which, after the age of seven, he never revisited but which haunted him throughout life. William’s father was a senior colonial administrator before dying prematurely in 1816 – leaving, in addition to his only legitimate child, a daughter by his Indian concubine. Thackeray was never entirely stable on the subject of race (particularly Indians); nor did he ever publicly acknowledge the existence of his half-sister Sarah.

His mother remarried. She had, before she married Thackeray’s father, loved another. The family resolved he was ‘inappropriate’ and misinformed her he had died. Something more appropriate was arranged. It was a cruel trick, but a not unknown practice among her class, for whom class was everything. After the death of her husband, Thackeray’s father, she discovered the existence of this supposedly dead first love. He became her second husband.

Thackeray never knew his father but loved his stepfather, and immortalised the old gentleman as his Quixote de nos jours, Colonel Newcome, in The Newcomes (serialised 1853–5). His evangelically severe mother he was never quite sure about. She is depicted as the morally stern Mrs Pendennis, in his second full-length serial. The depiction did not amuse her.

Infant William was returned to England, aged seven, to receive the education of a gentleman at Charterhouse and Trinity College, Cambridge. On the way back, the ship touched at St Helena, where he caught a glimpse of Napoleon – sowing the seed of a lifetime fascination with the Napoleonic Wars. The seed would bloom into Vanity Fair.

An idler at school, Thackeray left Cambridge a most undistinguished graduate, having lost much of his sizeable patrimony gambling. On the way down, he picked up venereal disease, which hastened his death and caused him lifelong urethral difficulties. (On being introduced to a Mr Peawell in later years, he sighed ‘I wish I could.’) On the plus side, his early errors supplied the raw material for his fine Bildungsroman (self-portrait novel), The History of Pendennis (1850). Novelists waste nothing – not even their own wastefulness.

After false starts in law in England, and drawing and journalism in Paris, the prodigiously gifted but wayward young man embarked on a ten-year-long stint, ‘writing for his life’ with anonymous or pseudonymous ‘magazinery’. He wrote under a mass of noms de plume, around thirty in all, belonging to invented characters from all walks of life.

A roll call of ‘the other Thackerays’ would include Michel Angelo Titmarsh, OFC (Our Fat Correspondent), Mr Snob, Mr Roundabout, Yellowplush (a flunkey, with an uncertain grasp of orthography), and his comrade of the servant world C. Jeames de la Pluche, George Savage Fitz-Boodle, Esq, and Major Goliah Gahagan. It was an apprenticeship but, at the standard penny-a-line, a tough one. He could have gone under at any point.

By 1836 he had squandered what remained of his personal fortune and had improvidently married an Irish girl with no dowry. Having borne him two daughters, poor Isabella fell into incurable insanity and was discreetly put away. Thackeray could now never marry – unless, as Mr Rochester intends in Jane Eyre, bigamously. When Charlotte Brontë’s novel came out there was absurd gossip that she and Thackeray were indeed clandestine lovers. It did not damage their sales.

By the early 1840s, Thackeray had made a reputation for himself as a savagely cynical satirist. He had his first unequivocal success as a writer with The Snobs of England (1846–7), published in the congenial columns of the newly launched magazine Punch.

At the same time that the snob papers were enlarging Punch’s sales by 5,000 copies a week, Thackeray was nursing a more ambitious narrative, something he initially called ‘A Novel without a Hero’. Eventually Vanity Fair, as it was brilliantly renamed, came out in Dickensian monthly instalments, at one shilling, 32-page parts, illustrated by the novelist himself. He was, at this breakthrough moment in his career, some thirty-five years old and had published millions of words, but this was the first work to proclaim the name William Makepeace Thackeray to the world. He was a penny-a-liner no more.

Success mellows a man, and Thackeray’s world view was markedly less cynical after Vanity Fair. It also accompanied important changes in his domestic arrangements: he set up home in Kensington with his daughters and – while remaining a clubman – was also a paterfamilias and less the bohemian. Thackeray had a number of grand projects as a writer once fame had come his way. Prominent among them was a desire to raise what he called ‘the dignity of literature’: to make it a gentlemanly occupation. No more Grub Street. It brought him into conflict with the supremely great novelist of the time, Dickens, whose early years gave him a better acquaintance with Marshalsea debtors’ prison (where his father was confined) than Trinity College Cambridge.

Most discriminating Victorian readers would have agreed that these two were the supreme male novelists of the mid-century. Some partisans would have gone so far as to agree with Jane Carlyle (Thomas Carlyle’s wife) that Thackeray ‘beats Dickens out of the world’. The truth is that Dickens, even in their lifetimes, outsold Thackeray by as much as five to one. But Thackeray got a more thoughtful respect from the critics than Dickens. John Gibson Lockhart (Walter Scott’s son-in-law), for example, dismissed Pickwick as ‘all very well, but damned low’. Personal criticism and insult were levelled at Thackeray in his lifetime (e.g. that in his later years he was a ‘mountain of blubber’). But no-one ever accused him, or his works, of being ‘low’.

The writers were polite about and to each other. And sometimes more. Dickens actually saved Thackeray’s life in 1849, when his rival succumbed to the cholera epidemic sweeping through London. Dickens sent his friend John Elliotson, the best doctor in London, to treat Thackeray. He dedicated his interrupted serial in progress, Pendennis, to Elliotson (‘I never should have risen, but for your constant watchfulness and skill’). Indirectly it was Dickens he was thanking.

Thackeray published his most ‘careful’ novel, the ‘three-decker’ History of Henry Esmond in 1852. The narrative – loosely modelled on Scott’s Waverley – is set in Thackeray’s beloved Queen Anne period. Like Thomas Macaulay and other proponents of the Whig thesis,1 Thackeray saw the early eighteenth century as the moment when British parliamentary democracy, and its middle-class hegemony, came into being. No guillotines required on this side of the Channel.

Thackeray’s career, in the tragically few years which remained to him, was glorious but none of his subsequent full-length fictions (The Newcomes, The Virginians, The Adventures of Philip) attained his earlier brilliance. But as editor of the newly launched Cornhill Magazine, with the highest-ever stipend of his career, Thackeray created his last great pen name, Mr Roundabout. This ‘chronicler of small beer’ (as Thackeray called him), was arguably his supreme literary creation. No Victorian ‘prosed’ better, or in more voices, than William Makepeace Thackeray.

He did not live to enjoy his Kensington mansion, dying prematurely in 1863, aged fifty-two. The postmortem revealed that his brain was preternaturally large: something that surprises no one who reads his fiction.

Dickens delivered, a week or so after Thackeray’s death, a bittersweet obituary comment in the Cornhill:

We had our differences of opinion. I thought that he too much feigned a want of earnestness, and that he made a pretence of under-valuing his art, which was not good for the art that he held in trust. But, when we fell upon these topics, it was never very gravely, and I have a lively image of him in my mind, twisting both his hands in his hair, and stamping about, laughing, to make an end of the discussion.

Rivalry? Yes. But respect as well. Their writing careers had indeed been a kind of contest. But blessed the era which can boast two such writers as Charles Dickens and William Makepeace Thackeray.

—

What, though, underlay the prolific Thackerayan masquerade? Schopenhauer, that kindred spirit, notes the odd fact that person (what we really are) and personae (‘masks’ to disguise our real selves), are, at root, the same word. As T. S. Eliot puts it, our daily endeavour is to ‘prepare a face to meet the faces that you meet’.

Thackeray plays with the idea of his other selves in the tailpiece to Chapter 8 of Vanity Fair, in which he has come down to talk to the reader in propria persona, ‘in person’ (but has he?):

Thackeray’s ironic self-portrait in Vanity Fair

It is Thackeray, of course, as a confused little boy, wondering who on earth he is.

I began by recalling that my Thackerayan mission, once set on my way by Miss Jones, was to come close to the man himself. Did I strip off the last mask to find what lay beneath? No. Can anyone? No. Thackeray expressed the impossibility of our really knowing anyone else in one of his meditative asides in Pendennis:

How lonely we are in the world; how selfish and secret, everybody! … you and I are but a pair of infinite isolations, with some fellow-islands a little more or less near to us.

1. Bluntly that the wellbeing of England could be entrusted to well-meaning leaders of an otherwise Tory disposition. It was refined in Disraeli’s ‘One Nation’ Toryism.

– NOTE TO READER –

The samples of Thackerayana in the following pages are arranged chronologically, and comprise essays, articles, extracts from longer works, and cartoons – a feast of many dishes.

None of them, I think it is safe to say, can be fully understood without some foreknowledge of the circumstances in which they were produced; nor without some brief explanation of references which his contemporaries picked up but will be elusive to the modern reader.

– A Gambler’s Death –

Signed ‘M. A. Titmarsh’ – from The Paris Sketch Book (1840)

Before photography established itself, the ‘sketch’ with pen or pencil was the way of freezing the fleeting moment. In a sense all Thackeray’s writing could carry the subtitle he gave Vanity Fair – ‘Pen and Pencil Sketches of English Society’.

The Paris Sketch Book was Thackeray’s first full-length publication. The title is misleading. It is a compendium of occasional writings. Some, like ‘A Gambler’s Death’, were gathered under the pseudonym Michael Angelo Titmarsh.

In this tale, Thackeray draws on his own experience of Charterhouse, a public school. ‘The story is, for the chief part, a fact,’ he asserts in a footnote.

Jack Attwood, Titmarsh’s old schoolfriend from Charterhouse, is a military hero ruined by drink and gambling. This, Thackeray feared, could be his own destiny. His biographer Gordon Ray notes, ‘until he lost his fortune, Thackeray was totally unable to overcome his compulsion to gamble’. He was, moreover, what card sharpers called a ‘gull’, or ‘pigeon’, easily separated from his money.

The Paris Sketch Book is dedicated, rather quaintly, to a French tailor who loaned the author a thousand francs when he was hard up. That money could well have gone on the casino tables.

A nybody who was at C— school1 some twelve years since, must recollect Jack Attwood: he was the most dashing lad in the place, with more money in his pocket than belonged to the whole fifth form in which we were companions.

When he was about fifteen, Jack suddenly retreated from C—, and presently we heard that he had a commission in a cavalry regiment,2 and was to have a great fortune from his father, when that old gentleman should die. Jack himself came to confirm these stories a few months after, and paid a visit to his old school chums. He had laid aside his little school-jacket and inky corduroys, and now appeared in such a splendid military suit as won the respect of all of us. His hair was dripping with oil, his hands were covered with rings, he had a dusky down over his upper lip which looked not unlike a moustache, and a multiplicity of frogs and braiding on his surtout3