Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Barbara Cartland Ebooks Ltd

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

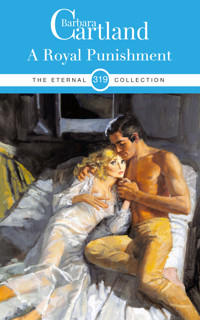

- Serie: The Eternal Collection

- Sprache: Englisch

By edict of her Godmother, the Queen, lovely young Clotilda is shipped off to an obscure Balkan nation to marry its sexually depraved and sadistic reigning prince. Her reluctant escort is a dashing and devilish Marquis, loved by London Society's ladies as much as he's loathed by their jealous husbands. As his innocent young charge is attacked and then kidnapped by murderous brigands, he loses his heart - and the Marquis's royal punishment becomes an all-consuming labour of love.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 222

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Author’s Note

Flogging was, in the Royal Navy, with the terrible “cat o’ nine tails”, the standard punishment for centuries.

Startling facts from the ship’s logs show that it was no deterrent. It is also obvious that the men of the eighteenth century were inordinately tough.

On Nelson’s flagship The Victory, on watch in Toulon and later in the War, between January and July 105 men were flogged, 13 of them more than once.

One of them was punished four times in this brief space of time: January 10th with 12 lashes, March 5th with 36, April 5th – 48, and May 24th – 48.

His offences were theft, drunkenness, more drunkenness and more theft. Other common crimes were insolence, uncleanliness, sleeping on watch, fighting, neglect and disobedience. Nelson’s Flag Captain Hardy was a stern man, and the Admiral did not interfere with the running of the ship. But Collingwood, who was ten years older than Nelson, treated his Captains as ‘assistants’.

As Nelson grew old, he rarely sanctioned flogging, and discipline did not suffer as one of the crew wrote,

“A look of displeasure from him was as bad as a dozen at the gangway from another man.”

In 1871, flogging was ‘suspended in peacetime’ and eight years later it was suspended in wartime, and it was ten more before the Army gave it up.

Chapter One ~1860

“Darling Stanwin, if only I could marry you, how happy we would be.”

The Marquis, who, feeling somewhat fatigued, was lying comfortably against the lace pillows, did not reply.

He had heard women say this so often that his mind had even ceased to react. He knew that if he told the truth, the last person he would wish to marry was the soft clinging creature whose head now rested against his shoulder.

“No lover has ever been as wonderful as you, darling, however much the poets may extol them!”

This again was something the Marquis had heard before, and he merely responded by pulling Lady Hester Dendall a little closer to him.

As he did so, it was a satisfaction to remember that her husband was on a special mission to Paris, so there was no chance of his being involved in similar circumstances to that which he had had to face a fortnight ago.

Then the Earl of Castleton, returning unexpectedly to his house in Park Lane and finding the Marquis and his wife in a compromising situation, had called him out.

Despite the fact that duels were frowned upon both by the Queen and the Prince Consort, they met in Green Park and, most unjustly, it was the Earl of Castleton who had been wounded in the arm, while the Marquis had got off scot-free.

That was what usually happened where the Marquis was concerned, and neither his seconds nor his friends were surprised.

But the Earl had walked off, swearing that sooner or later he would ‘get even’ with him.

The Marquis in consequence had been warned that he had a dangerous enemy, but he had just laughed somewhat cynically.

So many husbands had threatened him at one time or another, and because he was a crack shot, he had always managed to come out the victor in every duel and was afterwards completely unimpressed by anything they could say about him.

“I love you! I love you!” Lady Hester said passionately. “But if you are unfaithful to me again, as you were with Sheila Castleton, I think I shall kill you!”

The Marquis laughed.

“What with – a bow and arrow?”

“Do not be so unkind,” Lady Hester protested. “You know, dearest Stanwin, that I adore you, and it is agony to think that you have even looked at another woman!”

It was extraordinary, the Marquis thought, settling himself more comfortably, that women were never content with what they had, and always wanted more.

For Hester to be begging him to be faithful to her was rather like asking Niagara Falls to dry up, or King Canute ordering the tide to turn back.

All through his life the Marquis had found a pretty face irresistible and, although he was extremely fastidious, he found it impossible not to aim to win where other men had failed.

Granted that in the Social set in which he moved, the women on whom he bestowed his favours were experienced, sophisticated and in every case determined to attract his attention.

It was rather unfortunate, he thought, that while what to him was merely an affaire de coeur, the women in the case inevitably became serious and fell in love with him.

“I love you! I love you!”

He had heard the words repeated and re-repeated by soft voices until it was to him as familiar as the winds blowing outside the window or the birds singing in the trees.

“Think how happy we would be,” Lady Hester was saying rather dreamily. “We would undoubtedly be the most handsome couple in the whole of London and, wearing the Weybourne tiara, I would be the outstanding Peeress at the Opening of Parliament.”

Her fantasy was tiresomely the same as had been indulged in by a number of other women, and the Marquis merely closed his eyes and thought that as he was sleepy it was time he returned home to his own bed.

“I must go, Hester,” he said in a slow, lazy drawl, which, for some reason he had never been able to understand, women found irresistible.

“Go?”

Lady Hester’s voice rose in a scream as she spoke.

“Oh, no! How can you leave me? How can I let you go? Kiss me! Oh, Stanwin, kiss me!”

The Marquis, however, resolutely got out of bed.

He thought as he did so that the room was rather airless and Hester as usual had used too much of her favourite French perfume.

It certainly smelt exotic. At the same time, he had a sudden longing for the chill of the night, or the breeze that usually comes up from the river with the dawn.

Without thinking, without being aware that his body had the athletic proportions of a Greek god, he walked to the chair on which he had thrown his evening clothes and started to put them on.

Lady Hester, with her dark hair falling over her shoulders, watched him from the bed.

She was very beautiful, in fact the most beautiful brunette in the whole of London, and as her Irish blood had given her brilliant blue eyes, she was outstanding in every ballroom in which she appeared.

The daughter of an impoverished Irish Earl, she had made what was thought of as a ‘brilliant marriage’ to the wealthy Sir Anthony Dendall who was an up-and-coming young politician.

In fact, in White’s Club they were already betting he would be in the next Cabinet.

Sir Anthony had been head-over-heels in love with his beautiful wife when he had married her, but as he was politically ambitious, he had soon found there were more things to interest him outside his own house, than in.

This had resulted in Lady Hester taking a series of lovers, none of them, however, she admitted to herself, so important, so attractive, as the Marquis of Weybourne.

She had been determined that he would become her lover from the first moment she had set eyes on him.

It was a year before he had finally succumbed to her wiles and he had made her no promises of not finding other women equally interesting.

Wildly passionate besides being wildly in love, Lady Hester found it an intolerable torture to know that she never was sure what the Marquis was doing.

The news of his duel with the Earl of Castleton had been a bombshell, and while she knew she should have nothing more to do with the Marquis after such unfaithfulness, she found it impossible not to forgive him even though she would never forget.

There was a little edge to her voice as she asked now,

“Are you dining with me tomorrow night?”

“I cannot remember,” the Marquis said casually as he inserted a pearl stud into his evening shirt.

“What do you mean?” Hester asked sharply.

“I have a feeling that I have promised to dine with Devonshire – or was it somebody else?”

“If it is a dinner party, perhaps I also have an invitation,” Lady Hester said not very hopefully, “but, anyway, you will come to me afterwards?”

There was a little pause while the Marquis concentrated on tying his tie in the mirror that was over the carved marble mantelpiece.

“Shall I say I will think about it,” he said with a smile as he realised Hester was waiting for his answer.

“How can you be so cruel, so unkind to me?”

She sprang out of bed as she spoke and, naked, with her hair falling over her shoulders, ran towards him to fling her arms round his neck.

She looked exquisitely lovely as she did so, but the Marquis merely held her away from him.

“The trouble with you,” he said, “is that you are insatiable. You do not want one man, but a regiment of them!”

“If they all looked like you and made love like you,” Lady Hester replied, “I should be only too happy!”

She flung back her head as she spoke and looking up at him invited his kisses.

He looked down at her with a faint glint of amusement in his eyes and a slightly cynical twist to his lips.

Then he picked her up in his arms and carrying her across the room dumped her down on the bed.

“Behave yourself, Hester!” he said. “If you are very good I will either call on you late tomorrow evening, or perhaps we might dine the day after.”

She gave a little cry of joy and held out her arms to him.

“Kiss me once more before you go, darling Stanwin,” she pleaded.

The Marquis however walked back to the chair to pick up his evening coat and shrug himself into it.

It fitted without a wrinkle over his square shoulders, making his small waist and narrow hips seem more elegant than ever.

Lady Hester drew in her breath.

She had only to look at the Marquis to feel her heart beating frantically and her breath coming quickly from between her lips.

“Kiss me, please, kiss me,” she repeated.

“I have been caught that way before,” the Marquis replied.

He was well aware that if a man bent over a woman who was lying in bed she could easily pull him down on top of her, and then there would be no escape.

Instead, he took one of her outstretched hands in his, kissed it lightly and, without saying any more, went from the room, closing the door quietly behind him.

When he had gone, Lady Hester gave a little whimper of exasperation before she slipped under the bedclothes.

It was always the same, she thought, when the Marquis left her and she was never quite certain when she would see him again.

She had told herself a thousand times that he was as wildly in love with her as she was with him, and yet a fortnight ago there had been the episode of Sheila Castleton, and she rather suspected there had been other women before her.

“I love him! I love him!” she declared defiantly to the empty room, “and I swear I will never lose him!”

*

As he went down the stairs that were almost in darkness, the Marquis thought that Hester was becoming more and more importunate, and sooner or later Dendall was certain to hear of it.

There was going to be some interfering, meddling busybody ready to inform him of what was going on in his absence, and following the duel with the Earl of Castleton the Marquis felt that if he had any sense he should behave with more caution in the future.

He had known he was taking a chance in having supper with Sheila Castleton when she invited him to do so when the Earl was in England but, according to his wife, not returning from the country until the following day.

The Marquis had cursed himself for being so careless when everybody was aware that the Earl was extremely jealous and liable to return unexpectedly just to find out what his wife did in his absence.

It was extremely fortunate, the Marquis thought, that he had been on the point of leaving the Countess’s bedroom when the Earl had walked in.

He was dressed, so he was not in quite such an ignominious position as he would have been a half hour earlier.

But the Countess was still in bed, naked, and at the first sight of her husband she was so surprised that she sat up in bed, giving a shrill scream, which did nothing to help the situation.

If the Earl had had a pistol in his hand, the Marquis knew that he would have undoubtedly fired it at him.

Instead, with what was admirable self-control considering the violence of his feelings, the Earl told him to get out of his house – and that he would avenge himself in the usual manner at dawn in the customary place in Green Park, where they were unlikely to be seen.

“I intend to kill you, Weybourne,” he said, “so if you wish to say your prayers, you should start them now!”

The Marquis thought it best in the circumstances not to argue or enrage the Earl any further.

He merely left the bedroom with as much dignity as he could muster and walked deliberately slowly down the stairs into the hall.

He was aware as he did so that the Earl was watching him from the landing and that the night footman, who was opening the front door for him, looked white and shaken.

By the time he had changed his clothes and woken two of his friends to act as seconds, he only just had time to reach Green Park at the appointed hour.

“Why, in the name of the devil, do you want to fight Castleton?” Harry Melville had asked.

He had known the Marquis all his life.

They had been at Eton together, served in the same regiment, and he was in fact the only person in whom the Marquis ever confided.

“You know the answer to that,” he replied lazily.

“I knew that Sheila Castleton was after you,” Harry Melville said, “which is not surprising, but you must be aware that the Earl is both jealous and vindictive and it is a mistake to have him as an enemy.”

The Marquis shrugged his shoulders.

“He is only one of many,” he said, “and he should look after his wife more competently if he wants to keep her to himself!”

Harry Melville laughed.

“Really, Stanwin, you know as well as I do that unless husbands lock chastity belts on their wives every time they leave them, there is no other way of keeping them out of your arms!”

The Marquis did not reply.

He never boasted of his conquests and disliked talking about them, even to Harry.

At the same time, because he was so often in difficulties with jealous husbands, Harry was invaluable to him in many ways.

“This is the fourth duel you have fought in the last two years,” Harry was saying, “and quite frankly, Stanwin, I am fed up with having to get out of a warm bed to watch you appease some wretched husband’s honour. The result always is that he will have his arm in a sling for three or four weeks while you walk about unscathed!”

“Castleton is supposed to be a good shot!” the Marquis remarked.

“But not as good as you!” Harry replied.

Which of course, proved to be the truth.

Sometimes the Marquis wondered if it was worthwhile, but at the same time he knew that even if he ceased to pursue pretty women, they would still continue to pursue him.

Hester had lasted much longer than most of them, but this was due to her persistence rather than the Marquis’s.

She amused him, she was witty and spiteful in an entertaining manner, besides being like a tigress when they made love.

Sheila Castleton had been different and, if the Marquis were truthful, somewhat disappointing.

She was beautiful, there was no doubt about that, but she did not stimulate the same fires that Hester could do so effectively.

The Marquis knew that as far as he was concerned, the Earl of Castleton need have no fear that he would continue to covet his wife.

As Sir Anthony Dendall’s house in Park Street was only a very short distance from his own house in Grosvenor Square, the Marquis had sent away his carriage and walked home.

He enjoyed the exercise, the fresh air and the feeling that he was free for the moment, from clinging arms and hungry lips.

It was something he often felt after hours of lovemaking, and usually his thoughts then were of the country, his horses and his intention of winning every classic race with them.

Tonight, as he walked along, he told himself that he would be happy not to see so much of Hester in the future. In fact, he decided he had no intention of seeing her late tomorrow evening, or dining with her the following night.

‘She is not going to like it,’ he thought.

He found himself thinking of the undoubted attractions of a very pretty ballerina he had noticed the other night when he had attended a new ballet at Covent Garden.

He played with the idea that he might ask her to have supper with him tomorrow after the performance.

He was quite confident she would accept, whatever other arrangements she had made, but it struck him that at closer quarters she might be disappointing.

It was sad to think that many women were, whether one saw them on the stage or in the ballroom.

So often their allure seemed to come off with their gowns, and he continually found himself thinking it had all been a waste of time.

‘What am I looking for?’ he asked. ‘What do I expect?’

He told himself he was being unusually introspective, and it must be because he was tired.

His lips twisted in the cynical way that his friends knew so well as he thought that no one could spend several hours with Hester without being tired.

He reached his house in Grosvenor Square and the sound of his footsteps alerted the night footman quickly to open the front door.

He had been having great difficulty in keeping himself awake until his Master returned.

He thought now, as the Marquis walked in, giving him his tall hat and cane as he did so, that with any luck he would have a couple of hours sleep before the housemaids came bustling into the hall to clean and polish.

“Goodnight, Henry!” the Marquis said as he started to climb the stairs.

“’Night, My Lord!” Henry replied respectfully.

He put the Marquis’s hat and cane down on a chest and, having locked the front door, he settled himself comfortably in the padded chair, which was specially designed to keep out the cold of the long winter nights, and closed his eyes.

*

The Marquis, in his own bed, found himself unexpectedly wide awake.

He was thinking that he was bored with London and if he went away to Weybourne Park for a few days he would enjoy himself more than attending the endless assemblies, balls and receptions that were always part of the London Season.

He knew if he went away without any warning, a dozen hostesses would be extremely angry at his non-appearance at their balls, and those who expected him to dinner would be even more annoyed.

As for Hester… he shrugged philosophically.

Hester would miss him, and he was sorry if he upset her. At the same time, he knew with an insight that never failed him that their affaire de coeur was at an end.

The Marquis was usually ruthless and abrupt at the cessation of his love affairs simply because he found it impossible to pretend what he did not feel.

He expected perfection in everything around him, and therefore where his love affairs were concerned, he had long given up expecting anything sensational.

At the same time, when the fire of desire had to be slightly forced, he knew that the end was in sight.

He found that Hester was not only becoming too demanding and too monotonous in what she said, but also too clinging.

Being a strong character, the Marquis liked to dominate, and he did not like the woman to ‘make the running’. He wanted to be the hunter, not the hunted.

Because Hester was so overwhelmingly in love with him, she had ceased to let him take the initiative, and that, he knew, was something, if he were truthful, he found intolerable.

‘I will go to the country,’ he decided, and knew as he did so that it would soften the blow when Hester found out he no longer desired her.

Although she would undoubtedly bombard him with letters, to which he had no intention of replying, she would gradually he hoped, become aware that their association was at an end.

‘I will drive down with my new team,’ the Marquis decided, and fell asleep.

*

The morning however threw the Marquis’s plans into confusion.

He was called by his valet at the usual hour of eight o’clock.

He was just about to give the order for his chaise to be brought round in an hour’s time when his valet said,

“There’s a note for Your Lordship that’s just arrived from the Palace.”

“From the Palace?” the Marquis queried.

Havers produced a silver salver on which reposed a white envelope bearing the Royal Insignia.

The Marquis wondered what this could portend.

He opened it somewhat tentatively to find that it was signed by the Queen’s Private Secretary informing him that Her Majesty would grant him an audience at noon today.

As the Marquis had not asked for an audience with the Queen, he was aware this was a Royal Command.

He felt uncomfortably that it was something he should have expected of her.

Because he was quick-witted and extremely intelligent, the Marquis guessed without being told that the Earl of Castleton had taken his revenge in a more subtle manner than by killing him, as he had threatened to do.

The Marquis knew that there was no need for the Earl himself to go to the Queen and complain about his behaviour.

He had only to relate what had happened to his friend, Lord Toddington, a Lord-in-Waiting, who was known as the ‘arch-gossip of all gossips’.

He was, in fact, noted as being a danger both inside the Palace and out, for he repeated everything he heard either to the Prince Consort or to the Queen herself.

‘Dammit!’ the Marquis thought as he read the letter, ‘I bet this is Toddington’s doing!’

He was aware that his plans for leaving for the country would have to be postponed.

As he dressed himself appropriately for a visit to Buckingham Palace, he thought he would undoubtedly feel like a schoolboy being given a ‘ticking off’ by the Headmaster.

The Queen had made it quite clear, doubtless at the instigation of the Prince Consort, that she would not have any more duelling, though the ban had incurred quite an amount of criticism.

Duelling had been the gentlemanly way of settling an argument that had been accepted most amicably by George IV and tolerated by his successor.

Few duellists were actually killed, but if one was, it was customary for his opponent to disappear for several months to the Continent.

The whole episode was then conveniently forgotten, except by those who mourned the dead.

The Marquis was far too good a shot to do anything more than just wing his opponent in the arm.

Then, as the referee would consider honour was satisfied, the duel came to an end.

‘I might have thought,’ the Marquis told himself, ‘that Castleton was the vengeful sort and determined to have his ‘pound of flesh’, one way or the other.”

Because he felt defiant, not only in respect of what the Earl had done, but also because the Queen had become involved in it, he deliberately drove himself to Buckingham Palace.

It was considered correct for gentlemen calling there to arrive in a closed carriage.

The Marquis however swept in through the iron gates with their two sentries on guard, driving a pair of superb, perfectly matched horses, drawing a chaise that had only recently been delivered by the coach builders.

He drew his horses to a standstill under the pillared entrance to the State Rooms, handed the reins to his groom and walked in with an air which made the flunkeys in their Royal livery regard him with admiration.

They all followed his victories on the turf and often had a flutter on his horses, which invariably won.

As the Marquis walked up the red-carpeted stairs, one footman said to the other,

“I wish I’d had the nerve to ask ’im what ’e’s running at Ascot and get a good price!”

“Bet you won’t do that!” the other one replied with a grin.

The Marquis was escorted along the wide passage on the first floor towards the Queen’s private apartments.

They overlooked the garden at the back of the Palace and he saw, when he was announced and entered, that the sunshine was enveloping the room with a golden haze.

As he approached the Queen at the far end, he was aware she was looking stern and unsmiling, and he knew he was in for an uncomfortable interview.

Actually, the Queen had always liked handsome men from the time of her accession, when she had adored the handsome, raffish Lord Melbourne.

She was thinking now, as the Marquis walked towards her, that it would be difficult to find a better-looking man in the whole of the Court Circle.

The way the Marquis’s hair grew back from his square forehead, his finely cut features which betokened his aristocratic breeding and his athletic body, without an ounce of superfluous flesh on it, would have made him outstanding anywhere in the world.

The Queen, even if she was unaware of it, was beguiled like every other woman by the fact the Marquis appeared to regard life with a cynical amusement which set him apart from ordinary people.

It showed not only in the expression of his eyes but in the cynicism expressed by his firm, almost cruel lips, and the way he often drawled his words, as if he were completely indifferent as to whether anybody was interested in what he had to say or not.

Above all, he had a presence the Queen recognised as something she had always admired in a man.