Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

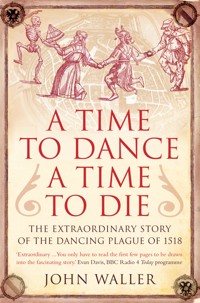

'A compelling 'whatdunnit'' The Times 'Waller's book should interest both historians and scientists, while the general reader will enjoy his colourful depictions of medieval life.' BBC Focus Magazine This is the true story of a wild dancing epidemic that brought death and fear to a 16th-century city, and the terrifying supernatural beliefs from which it arose. In July 1518 a terrifying and mysterious plague struck the medieval city of Strasbourg. Hundreds of men and women danced wildly, day after day, in the punishing summer heat. They did not want to dance, but could not stop. Throughout August and early September more and more were seized by the same terrible compulsion. By the time the epidemic subsided, heat and exhaustion had claimed an unfold number of lives, leaving thousands bewildered and bereaved, and an enduring enigma for future generations. Drawing on fresh evidence, John Waller's account of the bizarre events of 1518 explains why Strasbourg's dancing plague took place. In doing so it leads us into a largely vanished world, evoking the sights, sounds, aromas, diseases and hardships, the fervent supernaturalism, and the desperate hedonism of the late medieval world. At the same time, the extraordinary story this book tells offers rich insights into how people behave when driven beyond the limits of endurance. Above all, A Time to Dance, a Time to Die: The Extraordinary Story of the Dancing Plague of 1518 is an exploration into the strangest capabilities of the human mind and the extremes to which fear and irrationality can lead us.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 299

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2009

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

iii

A Time to Dance, A Time to Die

THE EXTRAORDINARY STORY OF THE DANCING PLAGUE OF 1518

JOHN WALLER

v

To my grandparents

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

In making the arguments that follow I am deeply indebted to the prior scholarship of a number of historians, including Justus F.C. Hecker, Alfred Martin, George Rosen, Francis Rapp and, above all, H.C. Erik Midelfort. A number of colleagues and friends have been very generous in translating key texts or helping me to improve my language skills: Anita Bunk, Harrison Kalbach, Laurel Ponist, Roland Demars, Laurent Dubois and Nicole Weber. For fruitful discussions or editorial comment I am grateful to Michael Waller, Richard Graham-Yooll, Abigail Waller, Adrian Horne and Katherine Dubois, as well as to Laurel Ponist, Daniel Dougherty, Ben Smith, Sean Dyde, Mark Largent, Robert Root-Bernstein, Michael Salzberg, Anita Bunk, Carrie and Charlie Green, Ann Brothers, Caroline Dawnay, Lesley Sharp, Claudia Stein and Eric Limbach. Several teachers are responsible for introducing me to the late viiimedieval world and inspiring me to write about it: Thomas Eason, Jeffrey Grenfell-Hill, Maurice Keen and Michael Mahoney. Susan Waller and Adrian Horne were inval uable assistants while in Strasbourg. And I would also like to say a special thank you to Gabrielle Feyler, Conser vateur of the Musée de Saverne, for her exceptional hospitality. F. Kuchly of the Societé d’Histoire et d’Archeologie de Saverne et Environs, Special Collections of Michigan State University Libraries, the Albertina in Vienna, and the Dombauarchiv of Köln, Matz und Schenk have all kindly permitted the reproduction of images. In addition, I am grateful to my students at the University of Melbourne and Michigan State University for fruitful discussions about the meaning of the dancing plagues. A travel grant from the Sesquicentennial Fund of MSU’s History Department helped fund my research in Strasbourg. The team at Icon – Simon Flynn, Nick Sidwell and Andrew Furlow – has been a delight to work with.

CONTENTS

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

1 Half bird’s-eye view of Strasbourg by Franz Hogenberg, contained in Georg Braun and Hogenberg’s Civitates Orbis Terrarum published in 1572.

2 Anonymous, The Meteor of Ensisheim, broadsheet with text by Sebastian Brant. Published in 1492.

Reproduced from J.H.E. Heitz, Flugblätter des Sebastian Brant (Strassburg: Heitz & Mündel, 1915). Courtesy of Special Collections, Michigan State University Libraries.

3 Albrecht Dürer’s portrait of Sebastian Brant. Silver point drawing of 1521.

4 From the title page of Sebastian Brant’s 1496 pamphlet on syphilis.

Reproduced from J.H.E. Heitz, Flugblätter des Sebastian Brant (Strassburg: Heitz & Mündel, 1915). Courtesy of Special Collections, Michigan State University Libraries. xii

5 An engraving of Joss Fritz by the German artist Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528).

6 Pen-and-ink drawing after Pieter Brueghel, known as Die Epileptikerinnen von Meulebeeck. Dated 1564.

© Albertina, Vienna. Reprinted with permission from Albertina, Vienna, Austria.

7 Altar painting in Cologne Cathedral, dated to around 1500, showing St Vitus on the viewer’s left and St Valentine on the right. Immediately below St Vitus, amidst the painted foliage, one can make out the image of three men dancing a wild ring dance.

Reprinted with permission of Cologne Cathedral.

8 Painted plinths below the images of St Vitus and St Valentine in Cologne cathedral.

Reprinted with permission of Cologne Cathedral.

9 Locations of the dancing mania in Europe 1200–1600.

10 The chapel of St Vitus according to Charles Muller in the early 1800s.

Reproduced by kind permission of the Societé d’Histoire et d’Archeologie de Saverne et Environs from Henri Heitz and Jean-Joseph Ring, Promenades Historiques et Archéologiques Autour de Saverne (Strasbourg, 2004).

11 Bas-relief wood carving of St Vitus, Mary and Marcellus before which the choreomaniacs of 1518 were led. Standing for centuries in the St Vitus shrine in Saverne, it is now housed in the Musée du Château des Rohan in Saverne. xiii

Photograph by H. Heitz. Reproduced by kind permission of the Societé d’Histoire et d’Archeologie de Saverne et Environs from Henri Heitz and Jean-Joseph Ring, Promenades Historiques et Archéologiques Autour de Saverne (Strasbourg, 2004).

12 Interior of the grotto of St Vitus above Saverne. One can see in the background the imposing keep of the bishop’s fortress of Greifenstein. Lithograph by Engelmann (1828).

Reproduced by kind permission of the Societé d’Histoire et d’Archeologie de Saverne et Environs from Henri Heitz and Jean-Joseph Ring, Promenades Historiques et Archéologiques Autour de Saverne (Strasbourg, 2004).

13 Jean-Martin Charcot inducing hysterical symptoms in a patient through hypnosis.

La Nature, Vol. 7 (1879), p. 105. xiv

xv

Madnesses of the past are not petrified entities that can

be plucked unchanged from their niches and placed

under our modern microscopes. They appear, perhaps,

more like jellyfish that collapse and dry up when they

are removed from the ambient sea water.

H.C. Erik Midelfort, Madness in sixteenth-century Germany

To every thing there is a season, and a time to every

purpose under the heaven:

A time to be born, and a time to die; a time to plant,

and a time to pluck up that which is planted;

A time to kill, and a time to heal; a time to break down,

and a time to build up;

A time to weep, and a time to laugh; a time to mourn,

and a time to dance …

Chapter 3, Ecclesiastes xvi

INTRODUCTION

The Dancing Plague

14 July 1518

Somewhere amid the narrow lanes, the congested wharves, the stables, workshops, forges and fairs of the medieval city of Strasbourg, Frau Troffea stepped outside and began to dance. So far as we can tell no music was playing and she showed no signs of joy as her skirts flew up around her rapidly moving legs. To the consternation of her husband, she went on dancing throughout the day. And as the shadows lengthened and the sun set behind the city’s half-timbered houses, it became clear that Frau Troffea simply could not stop. Only after many hours of crazed motion did she collapse from exhaustion. Bathed in sweat and with muscles twitching, she finally sank into a brief restorative sleep. Then, a few hours later, she resumed her solitary 2jig. Through much of the following day she went on, fatigue rendering her movements increasingly violent and erratic. Once again, exhaustion prevailed and a weary sleep took hold.

On the third day Frau Troffea rose to bruised and bloody feet and returned to her dance. By now, one contemporary recorded, dozens of onlookers had gathered, drawn by the sheer oddness of this remorseless spectacle. Tradesmen, artisans, porters, hawkers, cripples and ragged beggars jostled with pilgrims, priests, monks and nuns, and proud members of the patriciate: nobles set apart by their jewels, demeanour and sumptuous robes, and the wealthier burghers sporting fur-trimmed gowns and expansive turbans of folded silk. They watched as Frau Troffea’s dance went on deep into the third day, her shoes now soaked with blood, sweat trickling down her careworn face. Speculations flew among the onlookers. We are told that some blamed restless spirits, demons that had infiltrated and commandeered her soul. Perhaps through sin, they said, she had weakened her ability to resist the Devil’s powers. But the crowd soon decided that this affliction had been sent from Heaven rather than Hell. Accordingly, after several days of violent exertion, Frau Troffea was bundled onto a wagon and transported to a shrine that lay a day’s ride away, high up in the Vosges Mountains. If the authorities imagined that divine rage had now been quelled, they were quickly disabused. 3

Half bird’s-eye view of Strasbourg by Franz Hogenberg, contained in Georg Braun and Hogenberg’s Civitates Orbis Terrarum published in 1572.

Within days, more than 30 people had taken to the streets, seized by the same urgent need to dance, hop and leap into the air. In houses, halls and public spaces, as fear paralysed the city and the members of Strasbourg’s privy council despaired, they danced with mindless intensity. Day and night they went on, in clogs, leather boots or barefoot, their limbs aching with fatigue, their heels bleeding copiously, probably some with sinews torn to the bone. By early August 1518, the epidemic had begun to spread at an alarming rate. The numbers of afflicted 4rose each passing day so that soon at least 100 citizens were dancing with crazed abandon. Within a month, according to one chronicle, as many as 400 people had experienced the madness. And some time in late July, just a week or more after Frau Troffea had started to dance, the epidemic had taken on a cruel new face. A manuscript chronicle held in the city’s archives tells of what happened next:

There’s been a strange epidemic lately

Going amongst the folk,

So that many in their madness

Began dancing,

Which they kept up day and night,

Without interruption,

Until they fell unconscious.

Many have died of it.

Exactly how many fell dead we cannot know, though one chronicle suggests that (at least for a time) fifteen were dying each day as they danced in the punishing summer heat, seldom pausing to eat, drink or rest. Only in late August or early September 1518 did the epidemic finally subside, leaving many people bereaved and thousands more, in the city and beyond, fearful and bewildered. For over a month this terrible sickness had thrown into turmoil one of the largest cities of that sprawling collection of provinces and principalities known as the Holy Roman Empire. 5

This book tells the story of the dancing plague and seeks to explain why hundreds of people lapsed into a state of frantic delirium lasting days or even weeks. In doing so, it draws on a wide range of historical records, the analyses of several modern historians and insights from the disciplines of anthropology, psychology and neuroscience. Even amid the other horrors of the early modern age, the events of this dreadful summer lived long in people’s minds. Strasbourg’s crazed dancers had acted out one of the oddest dramas in recorded history, and so bizarre had it been that details were carefully recorded, in Latin and High German, by scores of different writers. Local merchants, officials, preachers, even the architect who redesigned the city’s defensive fortifications, left behind descriptions of the dancing mania. A few of these chronicles were compiled during the period of the epidemic itself. Others were pieced together, 50 or more years later, from caches of manuscripts stored by the civil authorities and from conversations with those who’d been in their youth in the early 16th century. There are also municipal orders relating to the epidemic issued by city leaders, as well as sermons and the descriptions of leading physicians. Having survived in the city archives for generations, the originals of some of these accounts were destroyed by high explosives during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870. Fortunately, much of the material had already been copied or transcribed by local historians and antiquarians. 6And from these diverse manuscripts we can now create a fairly clear picture of the events that led to this terrifying plague.

We owe the most detailed accounts of the epidemic to an irascible but brilliant alchemist and physician called Theophrastus von Hohenheim, better known as Paracelsus. He arrived in Strasbourg in November 1526 having spent much of the winter on the road, spurned by the elite physicians of other imperial towns as a medical heretic and suspected sorcerer. After passing through the Black Forest and across the Alsatian plain, he entered a city whose inhabitants were still trying to make sense of the bizarre horrors that had unfolded before them during the summer of 1518. Fiery preachers meanwhile reminded congregations of the dancing plague sent down by a wrathful Heaven to punish vile sinners. Paracelsus was fascinated. Self-proclaimed adept of the preternatural realm, whose mystical treatises were crowded with nymphs, demons, goblins, sprites and elves, he was determined to work out the meaning of this strangest of afflictions.

The explanation for the dancing mania offered by Paracelsus bore his characteristic blend of scepticism, mysticism and misogyny. He blamed Frau Troffea for her own wretched state. Noisy, idle and vindictive, she’d started to dance to humiliate her pitiable spouse. Only later did an irresistible urge take possession of her mind and body. In a mystical treatise of 1532, Diseases that Rob 7Men of their Reason, Paracelsus dubbed her disease ‘chorea lasciva’ and its victims ‘choreomaniacs’. Those whose thoughts are ‘free, lewd and impertinent, full of lasciviousness and without fear or respect’ are liable, he said, to develop a ‘voluptuous urge to dance’. The ‘whores and scoundrels’ who succumb, Paracelsus went on, need to have their deviant imaginations tamed by being locked in ‘a dark, unpleasant place’ and fasted on ‘water and bread’. Alternatively, he added, they might fashion images of themselves in wax or resin, transfer their thoughts and images to the model and then cast it into a fire.

In three books written during the decade following his arrival in Strasbourg, Paracelsus returned to the subject of the dancing madness. It’s just about possible, however, that he had heard of this mysterious sickness prior to arriving there. His father’s modest library high in the Swiss Alps contained a work by Johannes Trithemius, a German abbot and mystic, in which he described a terrible outbreak of dancing mania that spread across the Low Countries, Germany and north-eastern France in 1374. In fact, as many as seven bouts of uncontrollable dancing had occurred in various parts of western Europe prior to 1518.

The first is said to have taken place in a Saxon town called Kölbigk in about 1017, when several people danced riotously in a graveyard until an affronted priest cursed them to dance for an entire year. Unfortunately, it’s not 8clear if the Kölbigk legend is a parable based on a true event, or parable alone. No less ambiguous is a Welsh chronicle entry for the year 1188. Its author, Giraldus Cambrensis, told of an annual religious ceremony that took place at St Almedha’s church in South Wales during which dozens of people danced and sang around a churchyard until they ‘fell to the ground’, whereupon they began to enact ‘whatever work they had unlawfully done on feast days’ – some pretended to be mending shoes, others to be drawing thread and another to be operating a loom. They worked ‘as in a trance’, while tunelessly singing popular songs. Although they were clearly engaged in a ritual, the strange behaviour of these Welsh Sabbath-breakers has tended to be ascribed to the same cause as that which triggered the dancing mania of 1518.

German chronicles of around the same time speak of another apparent case of involuntary dancing. In the imperial town of Erfurt, during the year 1247, 100 or more children are supposed to have danced and hopped out of the town’s gates. Having reached a neighbouring settlement, they collapsed, sleeping by its walls and along the streets. The children were later found by their distraught and bemused parents; by then some of them were already dead and others were afflicted with tremors and fatigue for the rest of their lives. Some scholars argue that this story refers to a dancing plague. While the claim is unprovable, the detail about the survivors’ later 9symptoms does ring true. And it was only shortly after the Erfurt incident, in the year 1278, that about 200 people in Maastricht are said to have danced irreverently on a bridge over the River Moselle until, as a divine punishment, the structure collapsed and they perished in the turbulent waters below. This too has been interpreted as a case of compulsive dancing.

Far exceeding all these outbreaks in scale was the late-14th-century epidemic mentioned by the monastic record of Abbot Trithemius and several other chroniclers. Beginning in the Rhineland in the summer of 1374, probably among pilgrims from the Empire’s northern provinces, it would eventually extend all the way from Aachen and Ghent in the north to Metz and Strasbourg in the south. For several months, small bands of wild dancers wandered from place to place, spreading the affliction to local people as if by contagion. Chroniclers tell of thousands of men and women dancing while screeching with pain, leaping into the air, running madly from place to place and calling on the mercy of God and the saints. Perhaps the oddest detail of the 1374 epidemic is the claim that if sheets were not tied tightly around the dancers’ waists, ‘they cried out, like lunatics, that they were dying’. The dancers were assumed to be possessed by demons; some sufferers even roared out the name of a devil they called ‘Friskes’. And while most appear to have recovered bodily control within ten days or so, many relapsed one or more times. In disorderly bands those 10who had only temporarily recovered their reason travelled to holy sites, losing themselves to trance and wild dancing on reaching their destinations. In one case, hundreds of those in a briefly lucid state converged on a lonely, derelict chapel not from the town of Trier. There they ‘built huts with leaves and branches from the nearby forest’ and then, ‘possessed by demons and greatly tormented by them’, they resumed their dances. The epidemic subsided by the end of the year, though it may have struck again in north-eastern France in 1375 and the imperial city of Augsburg in 1381. From Liège and Trier to Utrecht and Cologne, priests performed rituals of exorcism, screaming ancient incantations down the throats of the afflicted and immersing others up to their chins in blessed water.

Of two far smaller dancing epidemics we also have records. The first took place in Zurich’s Water Church, so called for the bubbling spring water that pooled before its altar. The minutes taken at a meeting of local notables record that in 1418 several crazed women danced in the church, unable to stop, as a crowd of onlookers gathered around them. Another small group of mad dancers is mentioned in the ‘miracle book’ of the pilgrimage shrine of Eberhardsklausen, near the town of Trier, in an entry relating to 1463. In addition we know of several isolated cases during the 15th and 16th centuries, from Switzerland and the Holy Roman Empire, of choreomania gripping a single individual or an entire family. 11

The Strasbourg dancing epidemic begun by Frau Troffea was the second largest of Europe’s dancing plagues. But as it occurred after the invention of the printing press and in a city with at least the beginnings of a formal bureaucracy, it’s far better documented and by a richer variety of sources than any of its predecessors. Indeed, of all the outbreaks of dancing mania, this is the only one that can be reconstructed in detail. It also occurred at a critical moment in European history, when the Holy Roman Empire was teetering on the edge of savage religious wars and peasant rebellion. But if this account concentrates on the events of 1518, the earlier outbreaks will provide useful insights into the enigma of Strasbourg’s dancing epidemic.

The explanations for the dancing mania offered by Paracelsus and his contemporaries have not aged well. Nor have some more recent hypotheses. Several modern authors have sought a chemical or biological origin for these dancing epidemics, and the chief contender has been ergot, a mould that flourishes on the stalks of damp rye. Compounds produced by ergot can induce delusions, twitching and violent jerking. Millers in Alsace seem to have been aware of the risk, for the ends of the wooden pipes through which flour poured into waiting sacks bore horribly distorted faces, now believed to be reminders of the hallucinations that could ensue if the flour had been contaminated with ergot. These potent chemicals do not, however, allow for sustained dancing. Convulsions and 12delusions, yes; but not rhythmic movements lasting for days. And the agreement of chroniclers, physicians and clergymen is emphatic: the people danced. They may have hopped and leapt about too. There were no doubt also spasms and jerky movements, but witnesses in 1518, as in 1374, used the Germanic word tanz, meaning, unmistakably, ‘to dance’. There are two additional reasons to reject the ergotism hypothesis. First, it is simply not feasible for hundreds of people to have reacted in the same bizarre way to ergot poisoning. Second, while ergot can lead to delusions and spasmodic motion, it much more often causes restricted blood supply to the extremities, which in turn produces an awful burning sensation, gangrene and, often, an excruciating death. Crucially, there are no reports of what was called ‘St Anthony’s Fire’ from Strasbourg in 1518.

Other authors have explained the dancing plague as a form of hysteria, a physical expression of psychological distress. This is a more plausible hypothesis but in itself it provides no reason for why those affected danced rather than, say, wept, shouted, fought, fasted, shook or prayed. This book argues that the epidemic of 1518 did indeed prey on people suffering from the most acute anguish and fear. It was a hysterical reaction. But it’s one that could only have occurred in a culture steeped in a particular kind of supernaturalism. The people of Strasbourg danced in their misery due to an unquestioning belief in 13the wrath of God and His holy saints: it was a pathological expression of desperation and pious fear.

So to understand how Frau Troffea’s solitary dance came to engulf hundreds of people, we need to look at the vicissitudes of daily life in Strasbourg, at the traumas that belie Renaissance Europe’s reputation as a golden age of fine art and even finer feelings. For this was a world of terrifying uncertainty in which poor harvests triggered famine, devastating scourges such as plague, smallpox and the ‘English Sweat’ arrived suddenly to kill old and young, rich and poor, and remote communities regularly found themselves at the mercy of bloodthirsty bandits or foreign troops. This was the world, for many suffused with pain and dread, that inspired the nightmare canvasses of Hieronymus Bosch and the haunting image of ‘Christ as the Man of Sorrows’ by fellow German Albrecht Dürer. And it was a world so glutted with misery that nearly all ranks of society drank and danced whenever the opportunity arose, with the intensity of those in flight from an intolerable reality.

At the same time we need to enter into the minds of a people who were hooked on a mystical form of piety. The inhabitants of the Empire in the early 1500s imagined their world to be the embodiment of cosmic conflicts between good and evil, God and the Devil. Church doctrine infused almost every activity with supernatural meaning. Several times a week, if not every day, people 14attended religious services rich in magical ritual, their nostrils filled with incense smoke and the air charged with Latin incantations. Observance of the Church calendar also set the rhythm of daily life, while saints’ days marked the different phases of the year. Artisans even timed such routine tasks as the dyeing of cloth according to how long it took to mutter a Hail Mary or a paternoster. And, amid the humdrum preoccupation of staying alive during the late medieval age, the period’s poor hung on keenly to the prospect of eternal bliss in the next life and did what they could to expiate their sins in ritual bouts of penance and prayer. It was in this fervently supernaturalist context that Frau Troffea, and then hundreds of her fellow citizens, succumbed to the dancing plague. As such, the story of the dancing mania takes us into a largely vanished world of arcane ritual, beliefs, practices and fears. It explores a staunchly religious culture in which people took for granted that Satan and his servants stalked the Earth and that God and the saints hurled down arrows of sickness and death.

And yet this account of the crazed dancers of 1518 does more than tell of one of the most singular episodes in human history. It is also an exploration into the still relatively uncharted terrain of the human brain. In modern Western societies epidemics of dancing are virtually unimaginable. But the events of 1518 open a window onto some of the most extraordinary potentials of the human unconscious. Indeed, few episodes of mass 15hysteria come closer than the dancing plagues to defining the outer limits of what our minds can impel us to do in conditions of extreme distress. At the same time they draw our attention to the diverse ways in which psychic stress is articulated today. While the social and intellectual contexts have changed, the structures of our minds have not. So this book concludes by examining subsequent manifestations of the kinds of impulse that gave rise to the dancing manias of medieval and Renaissance Europe, including the writhing and blaspheming of ‘demonically possessed’ nuns, soldiers of the First World War rendered mute through fear, and men and women from all ages paralysed after traumatic psychological events. All these psychic phenomena remind us of the ineffable strangeness of the human brain. But none more so than the deadly dance that began in Strasbourg in the summer of 1518.

We begin the story a quarter of a century before Frau Troffea was seized by a compulsion to dance. Reflecting on the traumas and the unbridled supernaturalism of these years allows us to comprehend why so many people, for whom tragedy and uncertainty were nothing new, spectacularly fell apart. Even in a period accustomed to sudden reversals of fortune, the decades preceding Frau Troffea’s dance were exceptional in their harshness. Famine, sickness and terrible cold blighted and ended thousands of lives in Strasbourg and its environs. At the same time, a succession of disastrous events, from the 16onset of syphilis to the remorseless conquests of the Ottoman Turk, convinced many that God had turned His fury upon the people of Alsace. Just as alarming, many more nursed the dreadful apprehension that most of their monks, nuns and priests were far too idle and corrupt to be able to restore God’s grace. From the last decade of the 15th century, the humble of Alsace showed an unprecedented restlessness, a new level of aggression, hostility and fear. Empty bellies, gaunt faces, crippling debts, a profound distrust of landlords and clerics, and imaginations vibrant with terrible visions of ghosts, demons, devils and vengeful saints sapped the confidence of the poor in their ability to weather life’s storms.

This is a story of how a city’s people lost hope.

PRELUDE

Countdown to Crisis18

CHAPTER ONE

Signs of the Times

The portents for the new century did not look good. Many said it would be the last before Armageddon. In 1492, the year in which Columbus made landfall in the Caribbean and the Spanish monarchs expelled the Jews from their domains, a huge, triangular meteorite appeared over the horizon. Its luminous tail, streaking diagonally across the sky, was observed by a young boy near the town of Ensisheim, not far upstream from Strasbourg. He watched it, seconds later, thud into a nearby field. Alerted by the boy, a crowd of villagers rushed to the scene. Peering into a scorched crater, farmers, artisans and field-hands debated its significance.

To the people of late-medieval Europe things on Earth rarely happened by chance. Nearly every event had its origins in the supernatural. So when trying to find meaning 20 for the unexpected, savant and serf alike looked up to where they imagined Heaven to be: beyond the last of the crystalline spheres in which the planets were said to lie. Others looked to the stars and planets themselves. Unlucky alignments of planetary bodies were said to unleash floods, famines and plagues, and to determine the fates of empires and the course of individual lives. Many believed that God had created for everything on Earth an exact counterpart in the heavens; some even said there were as many fish in the sea as stars in the sky. And it was this symmetry between the earthly and the starry realms that allowed sages to prognosticate by working out future configurations of planets and constel lations. Nearly every royal court had an astrologer whose study of stellar motions informed the pursuit of war, statecraft and diplomacy. ‘By looking up I see downward’, summed up Tycho Brahe, Danish nobleman and astronomer.

Yet comets, meteorites and asteroids implied a more direct, if coded, communication from God. And so, in the nearby city of Nuremberg, worried chroniclers specu lated as to what horrors and natural disasters the Ensisheim meteor portended. Did it foretell the death of a king, a barbarian invasion, a wave of pestilence, or bloody peasant revolt? Meanwhile, the talented young lawyer Sebastian Brant, born in Strasbourg but studying in Basel, was convinced that this was a divine message with a clear purpose: God was telling His people to halt their wretched sinning. 21

Anonymous, The Meteor of Ensisheim, broadsheet with text by Sebastian Brant. Published in 1492.

In December, Sebastian Brant wrote a broadsheet with a woodcut image of the Ensisheim meteor crashing into fields before the moat that encircled the town. Beneath lay Latin and German rhymes telling of God’s righteous anger at his wayward people. Christendom was steeped in vice, said Brant. Miserable sinners all, His children had forgotten both Christ’s sacrifice and the awful flames of Hell. As a result, God had allowed the Muslim armies of the Ottoman Turk to destroy the ancient Christian empire of Byzantium. For Brant the Turkish advance could only be interpreted as a punishment for collective sin. For how could anyone feel that God still loved humankind when He permitted the infidel to gnaw at the flanks of Christendom? And, while the Turks geared up for fresh onslaughts, the Empire’s princes feuded reck lessly with their new Emperor, Maximilian I, and the French king threatened to invade his lands. 22

Brant begged the Emperor to restore faith and reason. Maximilian, partial to Brant’s analysis of worldly affairs, travelled to Ensisheim and had the giant fallen stone placed in a local church as a reminder of God’s wrath over the rank sinfulness of the times. He also reiterated his determination to mount and lead a Crusade against the Turk. But as the Sultan’s disciplined and battle-hardened soldiers conquered the eastern Mediterranean, others went to apocalyptic extremes. For some the awesome power of the Ottomans brought to mind the prophecies of the Book of Revelation. In paintings and woodcuts they appeared with sharp chins and narrowed, ferocious eyes, bent on Christian bloodshed. It seemed that Satan had been ‘loosed out of his prison’. ‘Gog and Magog’ had come bringing slaughter and ruin. The Beast waited in the wings.

Brant anticipated further disasters and humiliations for Christendom, but did not yet foresee the end of the world. By their wickedness humans had forfeited God’s love and they’d have to mend their ways to restore it. Having completed his law degree, Brant now emerged as a leading humanist, dedicated to restoring purity to religion and Latin discourse. And, as he studied the morals of the clergy upon whose piety so many depended, he recoiled in disgust.

Albrecht Dürer’s portrait of Sebastian Brant. Silver point drawing of 1521.

Back in Brant’s birthplace of Strasbourg, another humanist and scholar, Geiler von Kaysersberg, had spent the last decade upbraiding monks, nuns and priests for 23their vulgarity and worldliness. Geiler’s admirers dubbed him the ‘the Trumpet of Strasbourg Cathedral’ and came hundreds of miles to hear his oratory. The cathedral of Notre Dame, in which Geiler preached, soared magnificently over the city, its rose-coloured spire, façade and 24rose window intricate as lacework and replete with hundreds of statues of saints, sinners and devils. In the quiet coolness of the cathedral’s interior, sunlight streaming through towering stained glass windows dappled the floor and columns with colour. But if this was a place of great beauty, its resident canons were not always holy. And so, from a gorgeously carved stone pulpit, Geiler rebuked the clergy for setting the laity such a pitiful example. He did so with unfailing courage. His father had been killed while trying to protect villagers from a rampaging bear. Geiler showed the same brand of fearlessness in taking on the idle, whoring and rich-living clergy of the diocese, some of them scowling in the cathedral’s shadows as he reproached them for endangering the people’s souls. Not that he was always stern. Towards his congregation Geiler could be tender in the extreme. In fact, he had given up hearing confessions because he couldn’t bring himself to impose stiff penances on those who had committed serious sins.

As Brant worried about the Ensisheim meteor in 1492, Geiler addressed a synod of the Strasbourg church on the issue of reform. Before a gathering of 600 clergymen, ranging from the highest-born canon to the humblest monk, he poured verbal vitriol. Monks and nuns were accused of fornicating and then murdering their bastard children; five child’s corpses, he said, had been found buried in one local cloister. Other monks and priests shamelessly took concubines. And nearly all had far 25greater appetites for meat, drink and sleep than for prayer or pastoral duties. Geiler reminded the clergy of their responsibility towards the laity and that hatred for the Church grew daily. Now, at last, Albrecht of Bavaria, Bishop of Strasbourg, gave him the go-ahead to undertake a tour of religious houses and remedy their abuses.

Most of the clergy left the 1492 synod chastened but determined to resist. In most monasteries and nunneries, the asceticism of medieval founders had been long ago set aside. Gone were the beds of straw, the bland fare, the exacting regimes of song and prayer, and the abrasive, louse-infested hair shirts which, in constantly itching the skin and tearing open boils from infected pores, were meant to remind wearers of Christ’s agony on the cross. Many of the clergy, especially the canons and nuns, were the younger sons and daughters of nobles or wealthy burghers. They weren’t willing to forgo the rich tastes and styles they had acquired in growing up. And so canons and monks wore coiffured hair, daggers strapped to their belts and fashionable slippers; while nuns, who were meant to don habits of unfinished and undyed wool and to spend their days in silence or prayer, were to be seen visiting taverns wearing jewels, belts sparkling with gold and caps with ostrich feathers streaming behind. Rumours also spread far of them breaking their most intimate vows. A Dominican nun had recently been caught copulating with a hired workman. The abbess responded by locking the nunnery doors and banning 26males under 50 years of age from entering. This only excited gossip. After all, why would one need to imprison the sincerely chaste?