Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Polygon

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

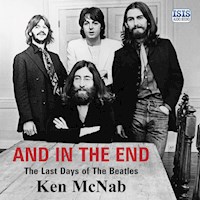

This is the story of the last acrimonious days of the Beatles, a final chapter reconstructing for the first time the seismic events of 1969, the year that saw the band reach new highs of musical creativity and new lows of internal strife. Two years after Flower Power and the hippie idealism of the Summer of Love, the Sixties dream had perished on the vine. By 1969, violence and vindictiveness had replaced the Beatles' own mantra of peace and love, and Vietnam and the Cold War had supplanted hope and optimism. And just as the decade foundered on the altar of a cold, harsh reality, so too did the Beatles. In the midst of this rancour, however, emerged the disharmony of Let It Be and the ragged genius of AbbeyRoad, their incredible farewell love letter to the world.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 546

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

AND IN THE END

AND IN THE END

THE LAST DAYS OF THE BEATLES

Ken McNab

First published in Great Britain in 2019 by Polygon, an imprint of Birlinn Ltd.

Birlinn Ltd

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.polygonbooks.co.uk

1

Copyright © Ken McNab 2019

The right of Ken McNab to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved.

Every effort has been made to trace the copyright holders. If any omissions have been made, the publisher will be happy to verify these in future editions.

ISBN 978 1 84697 472 4

eBook ISBN 978 1 78885 177 0

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available on request from the British Library.

Typeset by Studio Monachino

For the other half of the sky – in memory ofBridget, Kieran and Brian

© Evening Standard/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

All four Beatles climbed the stairs to the roof of the Apple building in Savile Row for their last public performance – played in the teeth of a bitter wind – that served as the climax to Michael Lindsay-Hogg’s film documentary Let It Be.

JANUARY 1969

All the rainbow colours of the outside world seemed to have been extinguished, replaced by a grim, cheerless darkness. The only sounds came from the heavy footsteps of two men – Mal Evans, the faithful roadie, and Kevin Harrington, the faithful gofer – lugging in guitar cases, amplifiers and drums, the sound of their heels echoing in the stillness. The guitars were positioned in a circle beside three chairs. Already in place stood a Blüthner piano. The drums were then mounted on a high-riser, the black lettering with the familiar dropped ‘T’ a clue to their owner.

Close by, people worked stealthily, checking camera angles and light meters. Men with headphones tested their audio equipment, checking noise levels. Snaking all over the floor and around the chairs were seemingly endless lengths of cables and wires. On the morning of 2 January, the sound stage at London’s Twickenham Film Studios was a hive of muffled activity. The only people missing, though soon to arrive, were the main players from Central Casting: John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr.

It was in these desolate surroundings that The Beatles hoped to get back to where they once belonged - back to the days when their music set in motion a chain reaction that altered western youth culture. A new year. A new hope. For the next couple of weeks at least, the studios would serve as their creative hub.

The premise was simple. The four most famous musicians in the world would be filmed writing and rehearsing new songs for a flyon-the-wall TV documentary. The pay-off would be their first proper live show since 29 August 1966, at Candlestick Park in San Francisco.

The prime mover, as he had been for the last two years, was McCartney, the Beatle-cheerleader-in-chief. ‘The idea was that you’d see The Beatles rehearsing, jamming, getting their act together and then finally performing somewhere in a big end-of-show concert,’ he recalled. Driven by a relentless work ethic, his enthusiasm for the group remained as full-on as ever. And so, it appeared, was the love held for them by fans who had been with them every inch of the way. Through early Beatlemania. Through the druggy mystery tour of the Summer of Love. Through the reinvented rock of The Beatles (aka theWhite Album).

Proof of their longevity lay in the fact that, as the decade entered its final year, The Beatles still sat imperiously at the top of the album charts on both sides of the Atlantic. The White Album, a four-sided record, had, despite its difficult birth, been hailed as an amalgam of pop, rock, country and soulful blues. But six years of unparalleled and dazzling success, combined with the relentless vagaries of fame, had taken an inevitable toll on relationships within the band.

Memories of the marathon sessions for the album, which was released in November 1968, were still fresh. The price for creating the music had been frayed nerves, angry bust-ups and, in the case of Starr, a week-long walkout.

By the turn of the year, McCartney, more than any of them, worried that the band was on life support, but he was not prepared to be the one to administer the last rites. He remained in denial over the serious disconnect that now existed between each of them. The cure, he was convinced, lay in a back-to-basics approach, the four of them creating great music in the studio and then going back on the road. Or at least playing a one-off gig to prove they could still cut it as a live band. He was even considering a surprise rock’n’roll-style drop-in, drop-out tour of northern dance halls. That was the fantasy he sold, and it was persuasive enough for them all to hook up at Twickenham on the second day of the year to begin sessions for a project tentatively and wistfully dubbed ‘Get Back’.

They were, of course, no longer the four callow kids who first stepped onto the world’s stage in 1963. Lennon had found Yoko Ono, the Japanese avant-garde artist seven years his senior for whom he broke up his marriage and with whom he dabbled in heroin. Harrison, having discovered a new inner confidence through Indian mysticism, was on a quest for Krishna consciousness. McCartney was enjoying the fame and acclaim that was his heart’s desire. And Starr, whose childhood had been wrecked by illness, simply couldn’t believe his luck at such a reversal of fortune.

But the symbiosis that once touched on telepathy had been replaced by lethargy. And now here they were, two days in to a new year, in a freezing studio they didn’t know, hemmed in and tapped out and working once again under an autocratic conductor: McCartney.

As she had been during the White Album sessions, Yoko remained umbilically attached to Lennon, an awkward situation which acted like dry tinder. Harrison simply wanted to be somewhere – anywhere – else; Starr had a ringside seat at the long goodbye. It was far too soon after the fractious atmosphere of the White Album to get back to the future, but no one had the courage to say out loud what needed to be said.

Lennon recalled: ‘Paul had this idea that we were going to rehearse or . . . see, it all was more like Simon and Garfunkel, like looking for perfection all the time. And so he has these ideas that we’ll rehearse and then make the album. And of course we’re lazy fuckers and we’ve been playing for twenty years, for fuck’s sake, we’re grown men, we’re not going to sit around rehearsing. I’m not, anyway. And we couldn’t get into it. And we put down a few tracks and nobody was in to it at all.

‘It was a dreadful, dreadful feeling in Twickenham Studio, and being filmed all the time. I just wanted them to go away, and we’d be there, eight in the morning. You couldn’t make music at eight in the morning or ten or whatever it was, in a strange place with people filming you and coloured lights.’

Lennon’s heart may not have been in it right from the start but he, like all of them, had initially appeared to buy in to the ‘Get Back’ project, the seed for which had been planted after their first appearance before a live audience for two years. That had been at Twickenham, too: they had showcased ‘Hey Jude’ and Lennon’s ‘Revolution’ before the cameras for Frost on Sunday. The clips, broadcast on British TV on 8 September, were directed by Michael Lindsay-Hogg, a talented American filmmaker, whose entry into the band’s orbit had come in 1966 when he oversaw the groundbreaking videos for ‘Paperback Writer’ and ‘Rain’.

The ‘Hey Jude’ video captures McCartney smiling angelically while seated at an upright piano with the band surrounded by roughly a hundred extras who were providing the ‘audience’. Looking back at the footage after fifty years, it’s hard to disagree with Lennon’s post-break-up assessment that he, Harrison and Starr had become McCartney’s sidemen.

But at the time all four were surprisingly pleased with the result. Denis O’Dell, head of Apple Films, said: ‘The “Hey Jude” promo is possibly more important than most fans realise. The Beatles’ unexpected enjoyment at performing for the clip was to be a key factor in the new direction that they were about to take. After shooting, we ran the final edit of the tapes in the recording truck. They were absolutely delighted. Drinking a whisky and Coke with them at four in the morning, we agreed a good night had been had by all. In fact, they had enjoyed it so much they suggested, there and then, that we should make another film. I was elated. That was the start of “Get Back”/Let It Be.’

But that was then – and this was now. And Lennon, always the prime mover in The Beatles’ power network, had almost no interest in going over old musical ground, with McCartney especially. The creative spark that once bound them was largely gone. He was bored with The Beatles and bored with his musical partner, who no longer stimulated him intellectually the way Yoko now did. They were different people, always had been. But they had always recognised in each other a friendly rivalry that drove the music. Now, though, they were rarely singing from the same song sheet.

Lennon’s dread was fuelled by more than just scorn over the music. Apple Corps, the company they had set up in 1967 as a multi-faceted Beatle business, was now haemorrhaging thousands of pounds a week due to a culture of spend, spend, spend that outweighed the money coming in. By the start of 1969, the company’s bean counters were warning that they faced bankruptcy unless serious steps were taken to address the losses. It was the ultimate corporate contradiction. The White Album had sold millions of copies while the success of ‘Hey Jude’ in singles charts across the world had also generated much income. The Yellow Submarine album, an ad hoc collection of oldies, new songs and instrumentals was released on 17 January to accompany the release of the film of the same name. Apple Records also included the likes of Mary Hopkin, whose debut single, ‘Those Were The Days’, had overtaken ‘Hey Jude’ at the top of the UK lists in late September 1968. But the accountants’ inescapable conclusion was that Apple was fast running out of cash.

Even before a note could be sung at Twickenham, there would have to be preconditions. None of the four wanted to repeat the formula of the White Album. Musically, The Beatles had always been about breaking boundaries, but they had been ceding ground to a new wave of groups, such as Led Zeppelin, Fleetwood Mac and the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, while contemporaries such as the Rolling Stones and The Who were widening their artistic boundaries; the Stones had just released Beggars Banquet, an acclaimed return to their R&B roots, while The Who had started recording Tommy, the first rock opera, in September 1968 (the landmark double album was released in May 1969).

Lennon’s solution was to ditch the high-end production values that had been the hallmark of their long-time producer, George Martin. The music would be stripped down, recorded warts-andall. Martin was relegated to an ad hoc role: Glyn Johns, who had worked with the Stones and Zeppelin on their groundbreaking debut album, jumped at the chance to man the desk.

‘It was funny actually,’ recalled Johns. ‘I got a phone call from someone with a Liverpudlian voice and I thought it was Mick Jagger taking the piss. Anyway, it was Paul McCartney. And you don’t turn down Paul McCartney. The idea was something like [Bob Dylan and The Band’s] The Basement Tapes, to show what they were really like. I’d worked with everyone and their mother by then, so I was quite used to being around people who were famous. But when I got the call, to walk in and be privy to those guys sitting around, doing what they did, and to be invited in, was pretty astonishing. I didn’t know them. I was the same as every other punter on the planet, who saw them as these extraordinary icons of marvellousness.

‘And although they could hardly be normal people, because of what their success had done to them,’ Johns added, ‘I was witnessing them being normal to each other. Which no one else had got to see, and which nobody really had a clue about. And so my concept of the record was: how fantastic to have a record of them playing live, sitting around mocking each other, just having a laugh. It was very weird. But George Martin, being the gentleman that he is, he realised that I had been compromised in a way, and he saw fit to put me at ease about the situation. He took me to lunch, and he said, “You’re not to worry about a thing.” I was feeling really awkward about the whole thing, and he was completely at ease about the situation.’

Johns was unaware that he had just signed a Faustian deal that would haunt him for at least the next twelve months. For the moment, however, his job was to coax the world’s greatest band back from the brink. But they were up already against the clock.

Starr had agreed to take a substantial role in a Peter Sellers film, The Magic Christian, Terry Southern’s anarchic comedy satirising America’s obsession with money, TV, guns and sex. Starr was due on set – at, coincidentally, Twickenham – in the first week of February, a timescale that instantly posed a creative challenge for The Beatles. And therein lay the crux of the problem: the Lennon and McCartney songbook currently contained only a couple of jewels and several unpolished stones.

In those first days of January, Lennon unveiled ‘Don’t Let Me Down’, ‘Child Of Nature’ (exhumed from the initial White Album sessions and later retooled as ‘Jealous Guy’, a stand-out track on Imagine), and ‘Sun King’. McCartney, on the other hand, arrived with several promising works in progress that would be given the full band treatment over the next week. These included ‘Golden Slumbers/Carry That Weight’, ‘Oh! Darling’, ‘Two Of Us’, ‘Teddy Boy’, ‘Junk’ and ‘Let It Be’ (a song that Lennon had little affection for) and ‘Maxwell’s Silver Hammer’(which Lennon simply loathed.)

In the early days, when they worked together, fine-tuning and editing each other’s material was never a problem for Lennon and McCartney. Now, though, they rarely wrote together. Which meant the naturally lazy Lennon was constantly trying to play catch-up to McCartney’s habitually prodigious output. Now expensively divorced from Cynthia, his obsession with Yoko continued to drive a wedge between him and the others.

He was also in thrall to heroin, a fixation that further alienated him from McCartney, who tended to stick to pot. Indeed, that month, during an interview for Canadian television, Lennon pulled a ‘whitey’ – junkie jargon for throwing up as he craved his next fix. His lack of new material betrayed the effect that heroin was having on his creativity, notably his lyrics, which had once been his strongest suit.

The fact was that, at the outset of filming for ‘Get Back’, Lennon and McCartney were ferreting around in their bottom drawers for decent material. That left them having to present snatches of half-finished tunes and half-baked ideas to their colleagues. Ironically, Harrison was armed with some of the best songs he had ever written. Encouraged by the material he delivered for the White Album – ‘While My Guitar Gently Weeps’ had been hailed as an instant classic – he had found his voice and was already channelling his assertive future self with songs such as ‘Something’, ‘All Things Must Pass’, ‘Hear Me Lord’, ‘Let It Down’ and ‘Isn’t It A Pity’. He had also co-written ‘Badge’ with Eric Clapton for Cream’s farewell album and was enjoying a new-found freedom playing with other musicians.

His self-confidence had been boosted by the kind of celebrity endorsement available to only a few. At that time, only Bob Dylan existed on a higher plane of credibility than The Beatles. In November 1968 Harrison had been invited to stay with Dylan and his family in Bearsville, near Woodstock, while Bob worked with The Band, the rootsy Canadian-American group that had garnered worldwide acclaim for the sheer diversity of their musical prowess.

Harrison marvelled at Dylan and The Band’s egalitarianism. It was the complete antithesis of his own situation.

Occasionally, during those dark January days at Twickenham, Harrison tried to tempt his bandmates into trying one of his songs. But they rarely took up the offer. ‘All Things Must Pass’ was given only rudimentary run-throughs and can be heard on bootleg tapes more as ghostly background noise to forced banter. Others, such as ‘Something’, would be given similarly brusque dismissals before the month was out. It wasn’t difficult to see the lyrics to ‘All Things Must Pass’ as an astute commentary on the band’s moribund state.

Over the next few days, Harrison would also roll out ‘I Me Mine’, the title of which also laid bare his antipathy. ‘It was like being back in the winter of discontent . . . straight away it was back to the old routine,’ he would later recall. ‘We had been together so long that we just pigeon-holed each other.’ Something had to give, and it did. On 6 January, four days after the sessions began, Harrison and McCartney squabbled over how to play a guitar part on ‘Two Of Us’. Their exchanges were caught on camera. McCartney tried to persuade Harrison – the Beatle he had known the longest – that his own feel for the song was the one that should hold sway. Harrison was tactful: ‘I’ll play what you want me to play. Or I won’t play at all if you don’t want me to. Whatever it is that’ll please you, I’ll do it.’

As he later told Rolling Stone: ‘My problem was that it would always be very difficult to get in on the act, because Paul was very pushy in that respect. When he succumbed to playing on one of your tunes, he’d always do good. But you’d have to do fifty-nine of Paul’s songs before he’d even listen to one of yours.’

The exchange has gone down in Beatles folklore as pointing to Harrison’s eventual make-or-break decision on his future with the band, but it would be another three days before matters really came to a head.

Chaotic as the sessions were musically, the most discordant note surrounded McCartney’s obsession with either a full-blown tour or a one-off show. McCartney, backed by Lindsay-Hogg, was keen to push the envelope. Discussions included talk of an amphitheatre in North Tunisia with thousands of fans holding torches and making their way to the venue across miles of sand dunes. An alternative was to hold it on board an ocean liner. Apathy, though, stonewalled every suggestion until, one day, McCartney’s patience snapped: ‘I don’t see why any of you, if you’re not interested, got yourselves into this,’ he told them. ‘What’s it for? It can’t be for the money. Why are you here? I’m here because I want to do a show, but I don’t see an awful lot of support. There are only two choices. We’re going to do it or we’re not going to do it. And I want a decision because I’m not interested in spending my days farting around here while everyone makes up their mind whether they want to do it or not. If everyone wants to do it, great. But I don’t have to be here.’

Harrison remained opposed to any live show, particularly one that he viewed as ‘expensive and insane’. Starr was adamant that he was not going abroad. Lennon vacillated between being up for anything and opposing everything. ‘I’m warming to the idea of an asylum,’ he remarked.

Harrison was vexed by yet another issue. As she had been during the White Album sessions, Yoko was impervious to all hints that her presence was unwanted, while Lennon revelled in the discomfiture of his friends. She often distracted him by kissing him or whispering in his ear during a take, causing him to miss a note or forget a lyric. It was virtually impossible for the cameras to get a shot of the four Beatles without Yoko being in the frame. It was obvious to everyone that Lennon, like Harrison, wanted to be anywhere but there.

At other times, Yoko would be Lennon’s voice in group discussions about how best to break the impasse, but the others knew better than to take him on. McCartney reflected: ‘He would have used that as an excuse to leave the band.’ Harrison preferred straight-talking, having, months earlier, told Yoko that she gave off ‘bad vibes’. Lennon struggled to control his temper then, but now, little more than a week into the project, the gloves were off.

On 10 January, Harrison’s tolerance snapped. Lennon was sabotaging the sessions, putting his own self-interest before that of the band, was continuing to patronise him personally and was treating them all with contempt. He railed bitterly at Lennon for his put-downs of George’s new songs, and brusquely added that he was leaving the band.

‘When?’ asked a startled Lennon.

‘Now,’ snapped Harrison. ‘See you round the clubs. Put an ad in the NME.’

Reflecting on the incident later for the Beatles Anthology project, Harrison attributed his departure to a number of factors, among them the presence of film cameras, which he found particularly annoying when The Beatles weren’t getting along. ‘They were filming Paul and I having a row. It never came to blows, but I thought, “What’s the point of this? I’m quite capable of being relatively happy on my own and if I’m not able to be happy in this situation, I’m getting out.” It was a very, very difficult, stressful time, and being filmed having a row as well was terrible. I got up and I thought, “I’m not doing this any more. I’m out of here.”’

Cameraman Les Parrott was part of the team assembled by Lindsay-Hogg and up-and-coming film-maker Tony Richmond. Though he didn’t witness this particular bust-up Parrott was sussed enough to know something was amiss when Lennon, McCartney and Starr returned to their instruments. ‘Well, George was missing for a start,’ he told me. ‘There was no reason for any of the crew to be told he had walked out or anything. But it was pretty awkward. We all knew something had happened and it was pretty serious.’

As for Yoko: ‘She was a blob in black,’ Parrott added. ‘Always there. You could tell the others resented it. Especially George. You had the feeling he wanted to say something. He used to just glower at Yoko.’

Lennon and McCartney’s immediate response to Harrison’s departure was to launch into an ear-splitting jam. Yoko eased herself into Harrison’s chair to lend her own inimitable vocals. It was the only time the cameras caught her smiling. Lennon betrayed the depth of his feelings towards Harrison by casually suggesting they had a ready-made replacement in Eric Clapton, Harrison’s closest friend. ‘If he’s not back by Monday, we’ll get Eric in,’ he declared. ‘He’s just as good and not such a headache.’

As it turned out, they wouldn’t have to approach Clapton, who would most certainly have refused to fill the gap left by his closest friend. But at that precise moment, The Beatles were victims of their own indifference and as close to breaking up as they had ever been. The candle that once shone so bright was nearly out.

*

Incorporated in May 1967, Apple Corps, its Granny Smith logo inspired by a Magritte painting, was Paul McCartney’s vision for the world’s first multi-media company. The band envisaged, in the parlance of the day, a happening – ‘Western communism’, they called it, a way of amassing cash and using it to become patrons of the alternative arts. They imagined Apple as a support network that would link artist to audience under various guises.

First came the Apple Boutique, peddling the regulation ’60s Hobbit-styled satin and velvet clothes, overseen by a team of Dutch designers called The Fool. Beatle wives dutifully modelled the stock for Rolling Stone. Lennon and McCartney even flew to New York for a media blitz to launch the venture. Impulsively, McCartney declared: ‘We’re in the happy position of not really needing any more money. So for the first time, the bosses aren’t in it for profit. If you come and see me and say “I’ve had such and such a dream,” I’ll say “Here’s so much money. Go away and do it.” We’ve already bought all our dreams. So now we want to share that possibility with others.’

Derek Taylor, the group’s urbane press officer, recalled: ‘They said they had set up this company and that anyone who had a dream could come and see them in London and they would make it come true.’ Taking them at their word, London Airport immigration was crammed with Americans identifying The Beatles as sponsors.

Apple’s philanthropic side was mainly McCartney’s baby, but Lennon was, initially at least, willing to lend a hand. He bristled at criticism in left-wing magazine Black Dwarf that Apple was a sell-out and that they only sang about revolution. He replied: ‘We set up Apple with money we as workers earned, so that we could control what we did.’ Except that The Beatles, in terms of managing a business, couldn’t control anything. Their manager, Brian Epstein, had supervised everything for them, insulating them from everyday reality.

Three months after Apple was formed, Epstein was dead from a drug overdose. Chaos quickly usurped order. By January 1969, upwards of £20,000 a week was leaving the company, and no one could account for where it went. ‘Apple,’ said Lennon, ‘was like playing Monopoly with real money.’ The Beatles accused everyone of ripping them off, while giving carte blanche to every opportunist to do just that. Such as Magic Alex Mardas, a young Greek entrepreneur who had assiduously courted Lennon and was the money-eating inventor of an electronic pulsing apple and the aptly named ‘Nothing Box’.

Or Stocky, the Massachusetts artist who sat on a filing cabinet and drew pen-and-ink drawings of genitals. Some California hippies even set up a commune in an empty office. ‘Apple,’ said Taylor, ‘had an aim, but it didn’t have enough order or structure. There were lots of vague phrases like “get it together” and “be there and just see what happens”.’

Harrison was working with Ravi Shankar, the Indian sitar maestro who was also his mentor in most other things. McCartney, more mainstream, was recording not just Mary Hopkin but also James Taylor, a young, honey-toned American singer-songwriter; Lennon was well down the road of indulging Yoko’s avant-garde whims. By January, The Beatles were attempting to fight on too many fronts as well as fighting among themselves.

The first casualty was the boutique. The Beatles announced they would give the clothes away. When they threw the doors open everything disappeared, carpets included. ‘All our buddies that worked with us for years were living, drinking and eating like fucking Rome. It was just hell, and it had to stop,’ raged Lennon. Apple had by now become, in the words of Epstein’s de facto replacement Peter Brown, ‘a mausoleum waiting for a death’.

Faced with the realisation that Apple was decaying from the inside out, drastic action was called for. When the evidence was presented in the bluntest of terms by a young accountant named Stephen Maltz, it was the wake-up call The Beatles never dreamt they would hear.

McCartney now had cause to regret his New York declaration. ‘I wanted Apple to run,’ he said. ‘I didn’t want to run Apple.’ Maltz’s warning was also his kiss-off to The Beatles, with whom he had worked throughout the Beatlemania years. He knew it was akin to a resignation note when he told them: ‘After six years’ work, for the most part of which you have been at the very top of the music world, in which you have given pleasure to countless millions throughout every country where records are played, what have you got to show for it? Your personal finances are a mess. Apple is a mess.’

The company may have largely been McCartney’s brainchild, but they were all accountable to the bottom line. In Maltz’s calculations, they had only earned ‘a pitiful’ £78,000 in 1968 and Apple’s spending was out of control. In the eighteen months up to January 1969, it had blown £1.5m – the staggering equivalent of £30m today. The Beatles had already spent £400,000 earmarked for investments by the accountants mostly on undeserving or far-fetched schemes. Apple even owned an upmarket London townhouse that no one could remember buying. Individually, they had hugely overdrawn their personal company accounts – Lennon by £64,000, McCartney by £60,000, and the other two each owed around £35,000.

Bill Oakes, Brown’s personal assistant, reckoned trying to control the company’s spending was like riding the back of a tiger. ‘John was always the most profligate spender. George was perhaps the most thrifty, but it is still ranging between £2,000 and £10,000 every week,’ he said. ‘Some [of the accountants] questioned why Mr Lennon was spending so much money on “sweets”. I had to point out they weren’t really “sweets”.’

Lennon was the first to feel the effects of the oncoming storm. He had always been consumed by an inner dread of ending up penniless ‘like Mickey Rooney’, forced to eke out a pittance on the cabaret circuit, singing songs like ‘She Loves You’ well into his middle age. The prospect now seemed perilously close. His divorce settlement with Cynthia had allegedly cost him £100,000. He had hired expensive lawyers to help extricate Yoko from her second marriage to American film-maker Tony Cox.

To complicate matters further, in January, Pete Best, the drummer they had fired while on the cusp of fame, brought a multi-million-pound defamation case against his former friends over a 1965 article, which suggested he had been axed due to a ‘pill-popping’ habit developed during their musical apprenticeship in Hamburg. The matter was quietly settled out of court later in the month.

It was obvious that The Beatles desperately needed a company doctor. To that end, Lennon set up a meeting, at McCartney’s suggestion, with Baron Beeching. Dr Richard Beeching was notorious in Sixties Britain as the man who had taken a cost-cutting scythe to the country’s nationalised rail network.

The meeting was short and far from sweet. Beeching cast a perfunctory glance at the Apple books Lennon had brought with him and curtly told him that he should ‘stick to making records’.

Other potential saviours such as Lord Arnold Goodman, an advisor to Harold Wilson’s Labour government, and media magnate Cecil King were discussed and discarded.

For McCartney especially, this was a fraught period. Not only did he have the Apple crisis to deal with, but in the studio he was the one bringing in the more fully formed songs. Fate, however, had offered up a potential solution. Linda Eastman, his girlfriend of the last ten months or so, had fallen pregnant just as filming began on ‘Get Back’. She had been living with McCartney in his home in St John’s Wood since late October, having abandoned her slightly erratic career as a photographer with Country Life magazine in New York. Her coltish looks and unfashionable dress sense rankled with the fans who huddled constantly outside his home and the Apple offices. McCartney, though, the last bachelor Beatle, was properly in love for the first time.

Linda came from New York wealth and, like Yoko, had attended Sarah Lawrence College. Her father, Lee, was a successful showbusiness lawyer whose client roster included some of the most famous names in the world. The family, part of America’s post-war nouveau riche, wanted for nothing. Her brother John was already enrolled as a partner in the family business.

Paul later recalled: ‘I remember when I first met John Eastman, I asked him, “What do you want to do? What’s your ambition in life?” He said, “To be the president of the United States of America,” which fairly soon after that he didn’t want to do. They were very aspirational.’

For McCartney, always the most class-conscious of The Beatles, Lee Eastman provided him with an entrée into American high society, and, suddenly, the solution to The Beatles’ problems seemed to present itself. Eastman had already offered him advice on how to make serious money by investing in music publishing and buying up the copyrights of other artists, adding that he should even consider setting up his own, stand-alone company.

At some point in early January, Eastman notionally agreed to map out a financial road for Apple’s recovery, but McCartney quickly acknowledged that his bandmates would surely capsize the whole idea before discussions could take place. ‘He would have been good business-wise, but of course he would have too much of a vested interest,’ he recalled years later. ‘He would have looked after me more than the others, so I can understand their reluctance to get involved with that.’ Even so, a seed had been planted in Lee Eastman’s mind.

It is worth recollecting that, to the public at that time, Apple seemed to be a huge success. The music label was thriving. In addition to everything else, McCartney understood the importance of keeping Apple’s financial woes private. Like Harrison and Starr, he was well aware that a loose remark could spark disaster. Lennon, however, had a more cavalier approach. In an interview published in Disc and Echo on 18 January, conducted by Ray Coleman, a confidant of many years’ standing, he casually laid bare their travails in sixty-two words.

He told Coleman: ‘We haven’t got half the money people think we have. It’s been pie in the sky from the start. Apple’s losing money every week because it needs close running by a big businessman. If it carries on like this, all of us will be broke in six months. Apple needs a new broom and a lot of people will have to go.’

It was a provocative statement, one that would set in motion a dire chain of events. Even in those pre-internet days, Lennon’s remarks quickly echoed all over the globe. Wire services clattered out the story and newspapers had a field day with headlines that spoke of ‘Beatles Cash Crisis’.

Derek Taylor quickly discerned the implications. He said later: ‘By 1969 it was real madness. We didn’t know where we were . . . Apple was like Toytown and Paul was Ernest the Policeman. We couldn’t have gone on and on like that. We had to have a demon king.’

Across the Atlantic, sitting in his office off New York’s theatre district at 1700 Broadway, a pudgy, thirty-eight-year-old man, dressed in his customary turtle-neck sweater and sneakers and pulling on a pipe, read the stories with relish. Instinctively, his accountant’s mind was already reeling off the numbers. Without having to say it out loud, Allen Klein knew it meant just one thing: Gotcha!

*

George Harrison’s walkout on Friday, 10 January, had turned out to be more than a fit of pique. In fact, he felt so frustrated over the impasse between all four that he succinctly summarised matters in his diary for that day: ‘January 10. Got up. Went to Twickenham. Rehearsed until lunchtime. Left The Beatles. Went home.’

Over the weekend, discreet calls were made to coax Harrison back into the fold. Eventually, he agreed to a meeting between all four of them on the Sunday night at Ringo Starr’s house – the one place always considered neutral ground – and laid down the conditions for tearing up his resignation. But the meeting quickly broke up and Harrison again stormed out. This time it seemed like there was no way back. Not even Starr, always the architect of arbitration, could smooth this one over.

Unlike McCartney, Harrison didn’t have a reverse gear when it came to inter-band diplomacy. Lennon, numbed and dilatory due to his heroin habit, sat in stony silence whenever his bandmate berated him over their plight. Now, though, with The Beatles’ very future – and all their fortunes – on the line he would have to listen.

Over the years, tiny details have emerged of what happened during this attempt at appeasement at Starr’s house. But what has become clear is Harrison’s unbridled rage at Lennon’s abandonment of his own sense of self. One by one, he itemised his complaints. Lennon had very little decent new material to offer up for ‘Get Back’. He was fed up with being treated like some star-struck kid. Yoko had now become his mouthpiece in the studio and at band meetings when, if anyone was being brutally honest, she had no right to be there. His deferment to Yoko at every God-given opportunity was no longer tolerable.

Lennon’s artistic and emotional withdrawal, his increased dependence on Yoko and his sullen, stoned passivity had left them all in a state of abject surrender. It was a make-your-mind-up moment. When Lennon refused to even engage in the discussion, Harrison angrily picked up his jacket and headed for the door. The more things changed, the more they stayed the same.

One discussion caught on tape during the month reveals Starr trying to drum some common sense into Lennon over his lover’s constant presence at the sessions. But Lennon says, ‘Yoko only wants to be accepted, she wants to be one of us.’ Starr for once spoke for the three other band members when he said softly, ‘She’s not a Beatle, John, and she never will be,’ before Lennon, digging his heels in, managed to get the final word: ‘Yoko is part of me now. We are John and Yoko, we’re together.’

*

Sporadic conversations recorded between McCartney and Starr in the canteen at Twickenham before John and Yoko’s arrival often revealed McCartney’s frustration at being trapped in a nowin situation and his desperate attempts even then to try and find some kind of compromise. All his well-founded attempts to hold The Beatles together after Epstein’s death were in serious danger of rupture. His partner, and the man whose validation he cherished above everything else, had replaced him with someone he couldn’t quite fathom out. And he knew that confrontation would mean only one thing – Lennon would tell him to screw The Beatles. Bubbling under the surface, of course, was also the sight of a decaying Apple. But twenty-four hours after the meeting at Starr’s house broke up in acrimony and the same day that Lennon’s comments to Coleman became public knowledge, there was no way of avoiding the elephant in the room.

‘Yoko’s very much to do with it and she’s very much to do with it from John’s angle,’ McCartney declared in a hushed conversation with ‘Get Back’ director Michael Lindsay-Hogg during a break in the session. ‘There’s only two answers. One is to fight it and fight her and try to get The Beatles back to four people without Yoko and ask Yoko to sit down at [Apple] board meetings. Or the other thing is just to realise she’s there and he’s not to split with her for our sakes. But it’s really not that bad, they want to stay together, so it’s alright, let the young lovers stay together, you know. But it shouldn’t be “can’t operate under these conditions, boy”. It’s like we’re striking because work conditions aren’t right. Fuck that then. And John knows that. If it came to push between Yoko and The Beatles, it’s Yoko . . . okay, so they’re going overboard but John always does. But maybe if I can compromise they will compromise and maybe bend towards me a bit. But it’s silly neither of us compromising.’

Joining in the discussion, Lindsay-Hogg and Linda Eastman both got to the kernel of the problem – a lack of honest communication between all four. Lindsay-Hogg added: ‘It really would be terribly dispiriting if it doesn’t get together.’ Unwittingly, McCartney had touched on an issue that had been overlooked – John and Yoko were a couple in love and like any young lovers (John was still in his twenties, after all) they wanted to be free to show affection without feeling judged by others.

Harrison, meanwhile, away from the studio poured all his anger into a new song, ‘Wah-Wah’. Written on the day he walked out, the lyrics mined the same vein of frustration about the band as ‘I Me Mine’. When the song was heard on his debut album, All Things Must Pass, eighteen months later, no one was under any illusions about the target of his vitriol.

Sessions continued over the next couple of days, but little work was done. McCartney and Lennon finally realised that they had belittled Harrison once too often. Now it was Harrison who had the future of The Beatles in his hands. His ally, Derek Taylor, used all his charm to persuade him that he would be ‘doing the decent thing’ by coming home and at least completing ‘Get Back’. But he was not ready to return quietly.

At a second band meeting on Wednesday, 15 January, which lasted five hours, an uneasy truce was reached, provided everyone agreed to Harrison’s rules: No more crazy talk of a live show in far-flung foreign shores. And definitely no more Twickenham. This time no one faced him down. McCartney reputedly apologised for his authoritarian behaviour. Lennon kept quiet, for now. Another five days would pass before all four were in the same room again.

The one thing they all agreed on was not to return to EMI Studios in Abbey Road, which for them had become little more than a sound-proofed prison. The obvious solution was to opt for the new, 72-track state-of-the-art studio being constructed in the basement of the Apple offices by Alex Mardas. But when they saw the studio, it was clear that it was not fit for even the simplest purpose. Glyn Johns summed it up as a ‘disaster area’. Engineer Dave Harries said, ‘They actually tried a session on this desk, just one take, but when they played the tape back it was all hum and hiss.’

The band sent an SOS to George Martin, the man they had largely frozen out of the ‘Get Back’ project, to use his influence to let them borrow a mobile recording unit from EMI. On 21 January, all four were back in the round in the Apple basement. That same day, Starr was buttonholed by Daily Express showbiz reporter David Wigg for BBC Radio’s Scene and Heard programme, and responded to media claims of fist fights and bitter arguments amongst the band.

Were they all still as close? ‘Yes. You know, there’s that famous old saying, you’ll always hurt the one you love,’ he said. ‘And we all love each other and we all know that. But we still sort of hurt each other, occasionally. You know . . . where we just misunderstand each other and we go off, and it builds up to something bigger than it ever was. Then we have to come down to it and get it over with, you know. Sort it out. And so we’re still really very close people.’

He also downplayed Lennon’s comments that Apple was a corporate basket case. ‘We have spent a lot of money, because we don’t earn as much as people think. Coz if we earn a million then the government gets ninety per cent and we get a hundred thousand. And we, we didn’t sort of realise how much we were spending, you know. Like, someone pointed out, to spend ten thousand you have to make a hundred and twenty. But we just spent it as a hundred and twenty.

‘So what we’re doing now is tightening up on our own personal money and on the company’s money, you know. We’re not just giving as much away on handouts and things like that, you know, and as many projects. We’re gonna cut down a bit till we’ve sorted ourselves out again and do it properly as a business . . . but it’s not that we’re broke. On paper we’re very wealthy people. Just when it gets down to pound notes, we’re only half wealthy.’

The twenty-first of January was an ad hoc session that passed without incident, but the next day saw things kick into a higher gear thanks to a happy accident. A few months earlier, attending a Ray Charles concert at the Royal Festival Hall, Harrison had caught sight of a faintly familiar pianist hammering out funky R&B solos.

Billy Preston looked nothing like the scrawny kid from Houston whom Harrison had last seen in 1962 in Hamburg in the days of The Savage Young Beatles. Then, he and Preston, the youngest member of Little Richard’s band, had established a rapport. Now, seven years later, Preston was a key (and physically imposing) part of Ray Charles’ band.

Harrison put out the word for him to get in touch, unaware that Preston had already decided to catch up with his old friends from Hamburg. He rang Apple and was invited to 3 Savile Row. Footage shows him arriving at the studio on 22 January and being greeted warmly by The Beatles. Out of shot, Harrison might have been seen smirking.

Preston’s presence immediately saw an improvement in behaviour – the same way Clapton had put everyone on point when Harrison brought him in to play lead guitar on ‘While My Guitar Gently Weeps’ for the White Album. Preston might have been unaware of the band’s internal strife but he was not in the least fazed by their fame. He was simply delighted to get the chance to join in the jams on a no-questions-asked basis. His natural chirpiness was instantly infectious and spread itself to the band.

‘I think they had lost a bit of the joy of making music,’ he reflected later. ‘There wasn’t much bickering in the studio, because they were concentrating on music. But when we’d break for lunch, they’d start to talk about business. I was surprised to learn they’d gotten ripped off so many times. I learned a lot from them about that kind of thing.’

Preston could play anything from straightforward rock ’n’ roll to blues-tinged gospel songs to syncopated jazz. Those sessions were not the most relaxed that The Beatles had ever played, but Preston’s effervescence and instinctive playing did much to enliven it. ‘Billy was brilliant – a little young whizz-kid,’ McCartney recalled in The Beatles Anthology. We’d always got on very well with him. He showed up in London and we all said, “Oh, Bill! Great – let’s have him play on a few things.” So he started sitting in on the sessions, because he was an old mate really.’

Preston’s keyboard skills injected life into new songs like ‘Get Back’, ‘Don’t Let Me Down’ and ‘Let It Be’ as well as sharpening their focus and discipline on other acoustic numbers such as ‘Two Of Us’ and Harrison’s ‘For You Blue’. He added rudimentary keyboard textures to a song then called ‘Bathroom Window’, later retitled ‘She Came In Through The Bathroom Window’. He said, ‘Everyone was pitching in with ideas. They just let me play whatever I wanted to play.’

By the end of the week, Lennon was so enthused by Preston’s involvement that he floated the idea of him becoming a full-time Beatle. McCartney was quick to shoot the idea down with the remark that ‘It’s bad enough with four Beatles.’

They now had five days left, more or less, to finally nail down usable tracks for the album while devising a spectacular end to the film. No one, though, could find a way through that quandary. Harrison remained steadfast in ruling out a live show. Besides, added Starr, they were in no shape to play live in front of an audience for a whole gig: a couple of songs, maybe, but an entire show would be hugely embarrassing.

Most of the day was spent fine-tuning songs that actually made the grade. And, despite the maelstrom of the past few weeks, some of them were almost over line. Lost amid the bickering was the fact that there had been some moments when it all came together joyously. Just not in the one-take, no-overdubs ethos that had been the guiding principle of ‘Get Back’ from the outset.

On Monday, 27 January, day sixteen of the album sessions, the band ran through some fourteen takes of ‘Get Back’, one of which included Lennon’s mock introduction about Sweet Loretta Fart, thinking she was a cleaner, but actually being a frying pan. And they remained on the same page during new takes of ‘Let It Be’, ‘The Long And Winding Road’, ‘Don’t Let Me Down’ and ‘I’ve Got a Feeling’, all of which crept closer to standard. Lennon, especially, was in good spirits after hearing that Yoko’s divorce from Cox had just been made official. ‘Free at last,’ he hollered, casually forgetting that it had cost him thousands of pounds in legal fees. And that night he and Yoko had a furtive appointment that, ultimately, would set in motion a domino effect on all their futures.

*

‘Nervous as shit’ was how Lennon later described his frame of mind as he and Yoko walked into London’s upmarket Dorchester Hotel that evening. He felt strangely vulnerable and the reason was simple; he was heading for a secret rendezvous with a man who revelled in his self-styled image as a music industry shark, a guy whose long-avowed obsession ‘to get’ The Beatles made it sound like they were prey waiting to be devoured. And now Allen Klein, the fearsome manager of The Animals, The Kinks, Donovan and, most notably, the Rolling Stones, had the chance to bite down on his biggest victim yet – John Lennon, the de facto leader of The Beatles.

Klein knew the band was perilously adrift after Lennon’s public admission that Apple’s financial woes had left them in serious danger of going bust. To Klein, this meant the biggest band in the world, one that had made – and squandered – untold millions, was ripe for the picking.

In the story of The Beatles, Klein is cast as Satan incarnate, a character whose breath reeked of sulphur. On his desk in New York sat a plinth parodying the Twenty-third Psalm: ‘Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil, ’cause I’m the biggest bastard in the valley . . .’ Naturally, his reputation had preceded him, and Apple staff had been instructed to shield The Beatles from his increasingly aggressive phone calls. When he finally got through to Peter Brown, the closest thing the band had to a manager, his overtures were instantly rebuffed. Brown recalled how Epstein had shown Klein the door several years earlier for dismissing as ‘a crock of shit’ the deals that Epstein had brokered for his charges.

Klein, now, was persistent. Sending a message through Stones intermediary Tony Calder he reached Derek Taylor, who, eager to get the aggressive American off his back, persuaded Lennon that he had nothing to lose by meeting him, especially when The Beatles needed someone to manage Apple.

McCartney, Lennon knew, had already sounded out his prospective father-in-law Lee Eastman about taking on the job. Eastman’s first solution would be to delegate the task to his son John, who had already made a cursory examination of the band’s finances. He had also held an initial meeting earlier in the month with Epstein’s brother, Clive, over the possibility of The Beatles buying Nems, the Liverpool family firm that still banked a healthy twenty-five per cent management fee as part of the deal drawn up in 1967 before Brian’s death.

Taylor, while acknowledging the part he had played in bringing Klein and Lennon together, always seemed to have retrospective regrets. He recalled: ‘Klein is essential in the Great Novel as the Demon King. Just as you think everything’s going to be all right, here he is. I helped to bring him to Apple, but I did give The Beatles certain solemn warnings.’

Lennon had, in fact, met Klein briefly in December during filming for the Stones’ Rock And Roll Circus, but their conversation had been perfunctory. So much had happened in the seven weeks since. Lennon – and, especially, McCartney – knew that the Stones made more money than The Beatles despite selling fewer records – and there were five of them! So when Lennon arrived at the Dorchester with Yoko, he told himself to keep an open mind.

To their surprise, they found an Ordinary Joe shorn of big-business artifice, dressed in casual clothes and projecting an air of humility. Lennon recalled: ‘He was sitting there all nervous. He was all alone, he didn’t have any of his helpers around, because he didn’t want to do anything like that. But he was very nervous, you could see it in his face. When I saw that I felt better.’ Klein then got to work, using flattery as his weapon. He knew exactly which Lennon buttons to press. He emphasised the uncanny ways in which his own rough childhood had parallels with Lennon’s.

Klein never knew his mother, who died when he was young. Lennon’s mother Julia had died in a road traffic accident when he was seventeen. Klein’s father, a Jewish-Hungarian immigrant, worked in a butcher’s shop, and since he couldn’t afford to raise four children on his own, had placed the infant Allen in an orphanage, where he remained until he was at least nine (some sources say older). Eventually he was placed in the custody of an aunt (just like Lennon had been).

And now? He owned a yacht and worked from a plush corner office on the forty-first floor of a West Side office building in the Big Apple. He could afford to gloat about his success because he had earned it. It came as a result of a ferocious work ethic, utter fearlessness and a brain that devoured audits like a calculator. He worked by the rules of Brill Building business: he consistently helped his clients – chiefly by forcing audits on unwilling record companies, which almost invariably turned out to be hiding a few beans themselves – while helping himself.

Lennon was seduced.

Klein pointed out that there were four Beatles. McCartney wasn’t anybody’s leader! Where did he get off, treating the others as if they were merely sidemen? It was just what Lennon wanted to hear. Lennon also believed Ono was fully his equal as an artist, and that she wasn’t being paid proper respect – not by the other Beatles, not by society.

Klein had arranged for the hotel to serve Yoko the macrobiotic rice he knew she liked, and he lavished attention upon her throughout the dinner. He told Yoko he would find funding for her art exhibitions, and he would get her films distributed by the film studio, United Artists. Not only that, he guaranteed (preposterously) they would pay her a million-dollar advance.

According to Lennon’s later recollections, Klein also underscored his deep understanding of The Beatles by telling him that he knew precisely which songs Lennon had written and quoted large chunks of his lyrics. Only three people know whether this is true and two of them are now dead. But it seems on the surface to smack of Lennon spin, even allowing for Klein’s lasting impression on the couple. ‘He knew every damn thing about us, the same as he knows everything about the Stones,’ Lennon claimed.

Then, of course, came the question of Lennon’s own finances, and the real reason that had drawn him to the Dorchester. By quoting Lennon’s ‘Apple-is-going-bust’ comments back at him, Klein touched on John’s deepest fears – that he would end up on Skid Row. And he knew how to fix that in the same way he had once made Bobby Darin and Sam Cooke millions – by carrying out forensic examinations of the EMI and Apple books to get Lennon what he was rightly owed.

The first thing he would do was sideline John Eastman’s idea that they should buy Nems for a cool million. Klein told John: ‘I’ll get ya Nems – and it won’t cost ya a penny. I’ll get it for nothing.’ Quoting his favourite mantra – ‘Fuck You Money’ – he assured Lennon that initially he wouldn’t charge him a penny. He just wanted permission to look into his affairs and see what he could do on his behalf.

In his own account of the meeting, Klein said: ‘I didn’t propose anything, I don’t work that way. I just asked him “How can I help you?” That’s all, and after we broke the ice, it was a very personal sort of meeting. We were trying to get to know each other. He was scared to death about the money situation. How would you feel, sitting there damn near broke after having made millions and millions of pounds and about to end up with nothing except memories?’

Lennon would later describe Klein as ‘the only businessman I’ve met who isn’t grey right through his eyes to his soul’. That night, he sent a memo to EMI chairman, Sir Joseph Lockwood: ‘Please give Allen Klein any information he wants and full co-operation.’

If McCartney was ever aware of Lennon’s meeting with Klein in advance, he has never let on. When all four Beatles gathered at Apple the next day, Lennon wasted little time in blurting out the news: Klein was the right man to lead The Beatles back from the brink. ‘I don’t give a bugger about anyone else. Allen Klein’s the man for me,’ he said.

He later explained to Rolling Stone: ‘I had to present a case to them, and Allen had to talk to them himself. And of course, I promoted him in the fashion in which you will see me promoting or talking about something. I was enthusiastic about him and I was relieved because I had met a lot of people, including Lord Beeching, who was one of the top people in Britain and all that.

‘Paul had told me, “Go and see Lord Beeching,” so I went. I mean I’m a good boy, man, and I saw Lord Beeching and he was no help at all. Paul was in America getting Eastman and I was interviewing all these so-called top people, and they were animals. Allen was a human being, the same as Brian was a human being. It was the same thing with Brian in the early days, it was an assessment; I make a lot of mistakes character-wise, but now and then I make a good one and Allen is one, Yoko is one and Brian was one.’

In later years he would offer a more telling observation: ‘He was the only one that Yoko liked.’

Klein was thus now convinced that he could seize the Ultimate Prize: management of the biggest band in history. After John and Yoko had left the Dorchester, he stayed up most of the night, poring over newspaper cuttings about their finances and Apple’s future, while rehearsing a sales pitch that would pick apart John Eastman’s suggestion that The Beatles lay out a million pounds to buy Nems.

When Klein met all The Beatles the next day, he was high on braggadocio, low on detail. Over a couple of hours, he set out his stall to save Apple while making each of them richer than Croesus. Fuck You Money! Harrison and Starr, while not rushing to early judgement, committed themselves to at least hearing more, but McCartney’s disdain for Klein was instant and uncompromising. He was the first to leave the meeting, signalling he had heard enough. It was a grievous, tactical blunder because it ceded the higher ground to Klein and allowed him to impose a chokehold on Harrison and Starr.

He told them bluntly they were being royally screwed by the business establishment: Lockwood at EMI, Clive Epstein at Nems, Dick James at Northern Songs. All of them (allegedly) creaming off the top, and that’s before we talk about the leeches bleeding Apple dry: Peter Brown, Neil Aspinall, Derek Taylor, Alistair Taylor, all their Liverpool buddies-turned-hangers-on.

Klein’s words, coated in a thick, expletive-filled Brooklyn brogue, zeroed in on their darkest fears. With Lennon already in his corner, victory was a foregone conclusion. Harrison and Starr gave tacit approval for Klein to, at least, examine their financial affairs as well as Lennon’s.

For Harrison, the pull of Klein’s working-class aesthetic won him over. ‘Because we were all from Liverpool, we favoured people who were street people,’ he said. ‘As John was going with Klein, it was much easier if we went with him too.’ McCartney, though, remained unwavering in his opposition: ‘I didn’t trust him,’ he said.