Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Elliott & Thompson

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

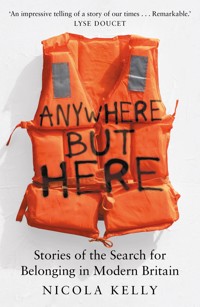

'A copy should be on every desk not just in the Home Office, but throughout government. A brilliant and hugely timely book.' Caroline Lucas, author of Another England What is it like to arrive on our shores with nothing and be pushed to the margins of society? Who stands to gain from an asylum system that is intentionally hostile? Anywhere But Here is a powerful exposé of Britain's broken asylum system and how it fails us all. Each year tens of thousands of people risk their lives to cross the Channel in small boats hoping to find safety in Britain. Yet the very system designed to protect them has all but collapsed. With unique and unparalleled access, award-winning journalist and former Home Office insider Nicola Kelly takes us behind the scenes of the small boats crisis for the first time. We follow the under-resourced coastguard overseeing search and rescue operations in the Channel. The decision-makers hired from McDonald's and Aldi to conduct 'life and death' asylum interviews. The immigration barristers securing last-minute reprieves for deportees who narrowly escaped death. And we step inside the Home Office corridors as ministers and advisors respond to emerging crises and scandals, from Windrush to the Rwanda plan. At its heart are the stories of war-torn arrivals, lone teenagers and trafficked women attempting to settle in cities, towns and villages across the UK. We travel to meet them, exploring where they have fled from and why, and the response of local communities to their new neighbours. Situated on the beaches and the ports, in the hotels, the courtrooms and the detention centres where the futures of those affected unfold, this is a searing investigation into one of the most urgent issues and shocking injustices of our time

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 474

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For those who arrived on our shores in search of a better life, those who never had the chance and those who died trying.

Contents

Prologue: No Entry

PART ONE: CROSSING

1. White Cliffs

2. SOS

3. Fortress Britain

PART TWO: ARRIVAL

4. On Solid Ground

5. No Safe Passage

6. Backlogged

PART THREE: DISPERSAL

7. No Room

8. The Black Market

9. Who Cares?

10. Advice Sharks

PART FOUR: INTEGRATION

11. Big Brother State

12. Raided

13. When The State Gives Up

PART FIVE: DEPARTURE

14. Locked Up

15. Say Goodbye

Afterword: Home

A Note on Sources

Acknowledgements

Notes

Index

Behind the Fence

Prologue: No Entry

In October 2024, I stood on a grassy verge overlooking a beach in northern France, the wind whipping through my hair and sand grains spiralling around my feet. Below, I watched as over sixty people were ushered towards a dinghy, carrying hand pumps and jerrycans of fuel. A chill ran up my spine as I saw a child – probably as young as three; my son’s age – gripping his mother’s hand and padding towards the sea, with only the moonlight to guide them. Rocking back and forth on the shoreline was the flimsy vessel that was to take them across freezing-cold water to the white cliffs beyond. Thousands of miles, largely travelled on foot, and here they were. Their final destination was in reach.

What is so extraordinary about this sight is how ordinary it has become. In 2018, less than 300 people crossed the Channel by small boat from the camps in northern France to the UK. Sajid Javid, then home secretary, broke off his holiday, declaring it a ‘major incident’.1 The following year, the Foreign Affairs Select Committee warned that closing off ‘robust and accessible’ passages would force more people into unseaworthy dinghies.2 And so it came to pass. By autumn 2024, just six years since the first dinghies left northern France, more than 140,000 new arrivals had come to our shores by small boat, fuelling a rise in far-right sentiment and a myriad of failed pledges and plans to stop them. How did we get here?

The UK’s asylum system has all but collapsed. A backlog of tens of thousands of claims has swelled out of control, leaving victims of torture, trafficking, persecution and conflict languishing in areas where local people don’t want them. Children have gone missing from hotels, exploited into criminal gangs. People have been made destitute and died due to lack of access to medical care, here on UK soil. They’ve been criminalised, made to stand trial and imprisoned, unable to afford the legal fees to prove their innocence. They have been monitored, followed, harassed and humiliated into leaving the country. And they’ve been deported back to the nations they fled, despite having narrowly escaped death there.

Creaking under the strain of a poorly resourced, ill-equipped system filled with disenfranchised, disaffected staff – both at a policy and at an operational level – successive governments have resorted to toxic rhetoric and headline-grabbing announcements. Under the Conservatives, the system was deliberately ground down, a crisis manufactured and seeds of division sown for political gain, with strong, eerie echoes of the pre-Brexit narrative on immigration.

Yet, by the government’s own reckoning, more than three-quarters of those who claim asylum here are granted leave to remain, considered by the Home Office to be genuine refugees in need of protection3 – a duty the UK has an obligation to uphold under international law. What’s more, asylum seekers are, in the main, welcomed by the general public. The World Values Survey found that the British public’s attitude to immigration is among the most liberal and relaxed anywhere in the world, with 68 per cent saying we should allow new arrivals to settle here – the highest of any nation surveyed.4 So why, if the public perception of migrants is broadly positive, has the government taken such a hardline stance?

Small boat crossings have become a proxy for the wider debate around immigration, even while the numbers arriving by irregular routes are only a tiny proportion of the overall figures. Asylum seekers account for just 0.5 per cent of the UK population today. We can – and we must – absorb these kinds of numbers. We are not, as many would have it, ‘full up’.

Covering these issues day-to-day as a home affairs reporter, it’s easy to become lost in the noise. Immigration is one of the most divisive issues in our society. Which side you fall down on – for or against open borders – can tell you a lot about a person. Where they live. Which socio-economic background they may come from. Even which way they voted in the EU referendum. This, unlike many others, is an issue bound up in identity. If you question someone’s view on immigration, you are questioning an important part of who they are: their roots, their values, their aspirations. It can be deeply offensive.

When I am asked what I do, where I work or what I write about, I usually pause, take a deep breath and make a face that suggests I am uncomfortable. Having worked for the Home Office as a press officer on the immigration desk during the rollout of the hostile environment policy, and as a spokesperson for the Foreign Office as the Arab Spring uprisings swept through the region, to now reporting on the asylum system for newspapers such as the Guardian and the Observer, these issues are personal to me. I often question my proximity to them and whether I am the right person to be working on these stories, or if shame and guilt cloud my judgement.

In tackling this subject, I’m frequently asked what I think the government should be doing. Should they stop the boats? Should they be putting new arrivals up in hotels? Should asylum seekers be given the right to work? I usually say it’s not my job to answer those questions and my views aren’t important. Whether the authorities can, or will, is what I focus on. My role is to report, not to opine.

To that end, this book is not about policy, politics or politicking; it’s about people. At its heart are the stories of those affected by the broken, sclerotic asylum system, many of whom I followed over years, from the moment they arrived on our shores and began to navigate the complex, notoriously hostile process to the conclusion of their cases.

Through their eyes, I have seen this country afresh: its ugly, hate-filled side and its kind, compassionate side too. I have been perplexed, angered and frustrated, found my security compromised, faced legal threats and, at times, felt that this is a society of which I no longer want to be a part.

That is nothing compared to those who have fled for their lives and the lives of those they love, who want nothing more than to find safety and peace and who, despite everything, still hold this country in such high regard. What must it be like to walk in their shoes, to be pushed to the margins, unable to access services, harassed, attacked and constantly looking over your shoulder? This book strives to find out.

Much has been written about the journeys people make along the now well-trodden migration route through Europe, but little is known about what happens when they reach the UK. For the first time, we will travel to the frontline of the asylum system, from the coastguard’s control room to the town halls and on to the hotels, the detention centres and the courtrooms where futures unfold, diving deep to understand how the system currently works and what needs to change.

We will see the ways in which the asylum system intersects with other parts of the state – healthcare, education, the labour market, housing, social care – by spending time inhabiting the worlds of an overseas care worker, a GP, a delivery rider and many more. Governments have consistently tried to isolate asylum seekers from other sections of society, but, as we will see, it is not possible to push newcomers to the fringes.

I have structured this book around what could be a linear process – crossing, arrival, dispersal, integration and, for some, departure – but which so often isn’t. In part, this is a way to show how the system is meant to operate and where it falls short. At every stage, there are problems left unresolved, lives ruined through chronic underfunding, shoddy mismanagement and sheer incompetence.

The title of this book, Anywhere But Here, refers to graffiti I saw scrawled on a wall running parallel to a makeshift camp in Dunkirk, written by a recent inhabitant, but it could be the message delivered by migrant spotters on a cliff in Dover, or the coastguard coordinating rescue missions. It may be the staff working at asylum hotels, getting away with abuse, harassment and humiliation of those they are paid to support. Perhaps it could refer to the Home Office subcontractors turning over tens, even hundreds of millions of pounds a year. It may, of course, be the far-right actors, but it could also be those who simply don’t want outsiders in their villages, towns or cities. Most likely it’s the Home Office and other central government departments who, through their policies and their rhetoric, are relaying the message that migrants are unwanted, unwelcome. ‘Go, anywhere but here.’

People move; people have always moved. Migration is part of the human condition. Throughout the centuries, the UK has experienced waves of immigration; communities which have shaped our national identity and which are now integral to the fabric of our society. Those on small boats are simply the latest iteration of that. How we respond to and absorb those in need is what matters.

We live in a divided society, but there is much that we share in spite of our political views. My hope is that the accounts in this book will appeal to a common humanity and empathy, to see beyond fear, anger and confusion to understanding and acceptance. Quite simply, if faced with conflict, persecution, torture and other forms of extreme violence, what would you do?

In the years to come, many will regard this as a pivotal moment in the history of our nation. By documenting the experiences of those who arrive on our shores from the earliest hours to their final moments, I hope to provide an insight into how our society treats those it has a duty to protect and the ways in which our government, and our institutions, fail them.

PART ONE

CROSSING

1. White Cliffs

‘When you leave your home for unknown shores, you don’t simply carry on as before; a part of you dies inside so that another part can start all over again.’

Elif Shafak, The Island of Missing Trees1

Asiren sounds, followed by a flash of torchlight. Less than 200 metres away, gruff voices call to each other, beating through undergrowth as they edge closer to the group. Arian can’t hear what they’re saying because a young boy huddled next to him – he guesses two, maybe three years old – is crying, taking in little gulps of air, while his mother hushes him and whispers prayers, hands open to the sky.

A stern, stout man thrusts a shovel into Arian’s hands and tells him, in Kurdish, to dig. Earlier that night, the man, known as Pasha, along with four other smugglers, had buried the inflated dinghy here behind the sandbank. Now it is up to Arian and other young people in the group to uncover it and get it down to the shoreline, fast.

With the voices getting louder, the passengers begin to panic, grabbing fistfuls of sand and throwing it behind them. Gusts of wind carry it back and into their eyes. The smuggler’s phone light is flashing around so much, Arian is afraid the police will find them. Then, finally, the boat comes free.

Several of the men in the group go first, launching themselves over the sandbank, then passing the dinghy overhead before resting it on their shoulders, five on either side. The men run into the sea until their chests are covered, with the remaining members following quickly behind them, four carrying fuel tanks.

As Arian reaches the water, he realises the engine has been left behind amid the panic. He takes a breath, sprints back up the beach and over the bank and grabs it between his arms in a bear hug. He concentrates on calming his breath in case the police patrol officers are near, but the outboard motor is heavy – fifty, maybe fifty-five kilos – and he staggers under the weight of it back down to the shore.

One of the smugglers uses a torch on his mobile to attach the engine to the back of the boat, pulling two metal bars down to secure it, then connecting a tube to the tank and making quick pumps on the bellow to get the fuel going. Wooden boards are placed in the bottom of the boat and hand pumps thrown inside. Phones are removed from pockets, wrapped in plastic bags and switched off. Arian is instructed to leave his on; he will navigate.

Another of the smugglers lifts the women and children on board, then sprints back up the beach and out of sight. Two others are in the water, pushing the boat out and forcing the starter cord into one of the passenger’s hands. The man resists; he’s never piloted a boat before and he can’t swim, but somebody has to steer and nobody else is willing. Before he can change his mind, Pasha leans over and pulls the shaft forward. With one sharp yank on the cord, the boat sets off.

It’s 10 p.m. when the group of forty-five leave the beach in northern France. The conditions aren’t as bad as Arian imagined – windy and cold, temperatures hovering just above freezing, but then he expected that, this being late January. He looks out towards the dark night, the moon guiding them, and wonders at how vast the sea looks from this perspective. Ahead, lights twinkle, blurry in the mizzle. ‘Not far,’ he thinks.

A twenty-mile stretch of sea is all that stands between the group and their final destination: the United Kingdom. Each of them has travelled many thousands of miles – 4,000, 5,000 for most – from Iraq, Iran, Sudan, Eritrea and further, from Afghanistan and India. It is, they hope, the last time they will have to make a journey like this. The last hurdle.

Arian thinks about the obstacles he’s encountered to get to this point. He regularly experiences flashbacks – intrusive, uncomfortable images of beatings, robberies and worse. ‘When you lose your life many times, you become not so afraid,’ he later tells me.

Within an hour, there’s no phone signal and no GPS. The app Arian is using to direct the pilot fails to open and the compass on his iPhone is stuck. The offline map isn’t working either. He begins to lose the feeling in his right leg, which, like the other men perched on the side of the dinghy, is in the water for balance.

Choppy waves mean the boat begins to take on water. Wind cuts through soaked clothes like a knife and quickly pushes the vessel off-course. One man tries to scoop water out using his remaining shoe; he lost the other running towards the sea. Another puts his daughter on the side rim of the boat, to keep her away from the cold water. The group shout to him in a mixture of languages.

Arian notices that the little boy he spoke to earlier is now sitting in the middle of the boat in his mother’s lap, staring wide-eyed into the distance. People around them are praying loudly and crying primal cries. The engine begins to sputter, straining under the weight of the passengers, before cutting out.

The group remain like this, adrift, for thirteen hours. When they can get a signal, they make frequent distress calls to both the French and the British coastguard, but nobody comes to their rescue. While many are paralysed with fear, unable to speak, Arian resigns himself to his fate. ‘I looked out at the ocean and thought “Maybe it is my time.”’

Then, at just after 11 a.m. the following day, he hears the sound of a helicopter overhead. A motorised boat pulls up alongside them with a dozen people on board. Arian notices that some are wearing military fatigues and he feels fear ripple through him. Another flashback.

Women and children are pulled up first, dead-weight and slipping. Arian feels a hand under his armpit and another pressing into his navel. He can’t stand without his legs collapsing beneath him – maybe it’s the cold, maybe exhaustion. His thoughts are confused, but he registers a certain numbness. He should feel elated, relieved to be alive, shouldn’t he? Instead, he feels nothing.

It took countless attempts for Arian to set foot on UK shores. In one week alone, he tried nine times to cross the Channel. On a December night, with the temperatures hovering just above freezing, he made three futile attempts. Each time came to the same, crushing conclusion: a police squad discovered the dinghy and stabbed through it, before chasing passengers back up over the sandbank. Soaked through and shaking uncontrollably, Arian huddled in bus shelters or on windswept beaches rather than risk missing an opportunity during the hour-long walk back to the camp.

It was becoming more difficult to cross now that the French authorities were patrolling the beaches. In March 2023, Conservative Prime Minister Rishi Sunak signed off a £500 million package to increase the number of police officers stationed on beaches along the coast of northern France.2 It was the sixth deal of its kind in under four years. The new measures included sniffer-dog detection teams, night-vision equipment, drones, helicopters, CCTV and border guards with the power to arrest.

A month later, at a camp near Grande-Synthe in Dunkirk, aid workers described to me events that had taken place the night before: a mother had been separated from her two children. They hadn’t been able to run from the beach police fast enough. Charity workers spent the next twenty-four hours frantically calling the local authority, hospitals and speaking to eyewitnesses, eventually managing to get her released from police custody and reunited with her children.

Later that evening I drove to a beach nearby, where Arian and many other contacts in the camps told me they had attempted the crossing. The path took me over a dusty train track past nuclear reactors at the neighbouring Gravelines power plant, puffs of smoke bellowing out into the adjacent camps. On the Opal Coast beyond lay a sweeping bay, almost desert-like with its soft, rippling dunes.

Empty as it was, I parked on the beachfront and took a bracing walk towards the shoreline. Oystercatchers and grebes flitted around, gulls soaring and squawking, angry to be interrupted. Fishermen had stationed themselves towards the east of the bay, baiting for cod and whiting, a cold-water paradise. And there, swilling around in a pool of water in the distance, was a strange black object, incongruous with the powder-white sand: a deflated dinghy, its rubber curled up and foaming with a fresh mixture of saltwater and sand. Half-buried close by was a trainer with the sole pulled away.

I paused a while, walking around the boat and contemplating the terror of those who had been in my place hours before, trying to imagine what they must have been thinking as they looked out to the horizon. I shuddered, fearing for the people I had met in the camps who would try again that night.

Before heading off, I posted a tweet with a fairly stark message about the deflated dinghy and how UK funding is being used by the French authorities to control the border. I was flummoxed by the response. ‘Bravo the French! Stop the illegals!’ one anonymised account cheered. ‘Good use of taxpayer’s money!’ another announced with glee, garnering over a thousand likes. Further down in the replies, I noticed a popular post that made me stop cold. It read: ‘Let them drown!’

Returning to the camp after a failed attempt to cross only exacerbates the distress. Many find that their tents have been slashed through, with the poles broken and any remaining belongings removed. These evictions, which take place every twenty-four to forty-eight hours in Calais and slightly less frequently – usually twice to three times a week – in Dunkirk, are designed to deter migrants from settling there. Arrests take place in the camps, too, with the CRS (Compagnies républicaines de sécurité) – the French riot police who carry out the evictions – routinely using brute force and detaining people on no-fixed-abode charges.

While most of those in the camps have experienced violence on borders along the well-trodden migration route through Europe, the humiliation, harassment and excessive use of force associated with these evictions baffles them. ‘You are journalist. When they destroy our tents, where do they want that we go?’ an Eritrean man slurping his sugary black coffee asked me one gusty afternoon. In truth, I didn’t offer him a particularly helpful response. The honest answer is that the authorities simply don’t care where they go.

The conditions in the camps are dire. There’s no shelter, no mains supply for drinking water, no food, no sanitation. They can’t be said to be refugee camps. With no UN presence – no UNHCR, no World Food Programme, no International Organization for Migration – underfunded grassroots organisations fill the vacuum, arriving daily, sometimes twice-daily, to deliver replacement tents, hot meals and bottles of water. When the aid vans arrive, groups run after them, calling out for them to stop and huddling close before supplies run out. Charity workers shout to form a line.

Roadblocks are used as benches and upturned shopping trolleys as chairs. Towards the entrance, groups of Kurds and Albanians have converted their tents into shops, selling fizzy drinks and trading cigarettes for croissants wrapped in plastic. Crows roam around, picking up crumbs.

Behind a barbed-wire fence, there’s a water tank on a mound where people wash their faces and refill bottles. Children sprint up and down the hill, some venturing behind shrubbery to a ditch beyond, used as toilet facilities. Their parents run after them, hauling them back and reprimanding them: it’s not safe down there, they warn.

SIM cards with ten minutes of free international calls are handed over from the back of the aid vehicles, names scrawled and ticked off. Some take the cards and run to the back of the line to get another one, hoping in the mêlée they won’t be noticed. Teenagers linger, trying to assert themselves. A fourteen-year-old Afghan boy travelling alone approaches me to ask if he can use my phone to call his mother. He promised he would contact her every day and it’s been three days; she will be worried.

Affable aid workers stroll around, clasping hands and practising salutations in Arabic, Albanian, French. One young man from Liverpool has taught himself Kurdish, impressing groups queuing at the vans; he came to Dunkirk for two weeks and has stayed for six years. Others man the portable shower facilities, chatting over a cigarette. There’s camaraderie, genuine friendships and a spirit of openness. I find myself forming easy connections, humbled.

At an activity table for children towards the entrance of the camp, I meet Parwen and her seven-year-old daughter, Shewa, who immediately begins painting my face with hot-pink lipstick and matching eyeshadow. Parwen talks openly about their encounters with the French authorities; a recent memorable attempt to cross had ended with a tear-gas canister landing next to her four-year-old son, Hozan. They had staggered away in the fog, her little boy bawling hysterically in her arms, terrified he had been blinded. When they got back to the camp, their tent was gone. I asked where they had slept. ‘Here, on this land,’ she says, showing me a picture of her two children standing on barren wasteland, ripped plastic bags attached to the shrubbery behind them. They had endured the harsh winter there and now they were beginning to lose hope.

It’s not just tents that get destroyed. Calais-based charity Human Rights Observers showed me video evidence of locals and members of the authorities stabbing through water tanks to deter migrants from settling there, leaving children as young as two without drinking water.3 One aid worker told me this happens so often that they now tend to carry around five-litre jerrycans of water and fill up bottles individually. Phones – those vital lifelines – are confiscated by the CRS without reason and, with them, the numbers of both their loved ones and their smugglers.

After each eviction, a coach – usually one, but sometimes more – waits on the dirt track beside the camp to take people to Lille, where they can claim asylum in France. Many do attempt to do this: France typically receives more than double the number of asylum applications compared to the UK. (In 2023, 167,432 persons registered to apply for international protection in France, while the UK received 67,337 applications in the same year.4) Others choose to make the crossing perhaps due to family ties, or because they served alongside the British military, or gained language skills and an understanding of the culture as a result of our colonial roots in their home country. For those who have tried and failed to secure leave to remain in France or other European countries on the migrant route, the journey continues. Many remain under the control of the smugglers, beginning the perilous return to Calais, Dunkirk and the surrounding areas and attempting, once again, to cross the Channel.

Three weeks after I left the camps, contacts sent me videos and images of a complete clearance.5 The CRS had entered the site carrying plastic shields and brandishing wooden batons. Bulldozers ripped through the land, hauling up tents, industrial washbasins and shopping trolleys. Saws and hammers razed anything that remained.

Walking single-file along a tarmac road running parallel to the camp, more than 300 people searched for a new place to rest their heads and wait for a chance to cross. Many formed new temporary settlements within 100 metres of the site, while others were pushed out into the forest.

Aware that people scatter in the immediate aftermath of an eviction but return to the wooded areas near the waterfront shortly afterwards, the CRS had recently started hacking down some of the trees to prevent migrants seeking shelter from the driving rain and biting winds. Late one night Parwen shared their location on WhatsApp and sent images of a fire built from scraps of wood, Hozan and Shewa huddled around it, wrapped in blankets. Underneath, she added a crying-face emoji.

Meanwhile, the French state provides nothing, other than funding for the CRS and coaches to bring migrants southwards. Without reaching the UK to claim asylum and with no pending claim in France, they are not officially asylum seekers. They’re also not refugees in legal terms, because they haven’t been granted refugee status in another country or had their claims assessed and confirmed by the UN. They are considered migrants and therefore not eligible for even the most basic provision.

As I drove away from the camps to begin my safe passage to the UK – a journey everybody there is so desperate to make – I saw the graffiti that stopped me quite literally in my tracks. It read: ‘Anywhere But Here’.

*

All this – the conditions in the camps, the evictions, the numerous futile attempts – made Arian even more determined to reach the UK. It wasn’t difficult to locate his smuggler in this chain of the network. Like Arian, the facilitators were predominantly Kurdish, from Iran as he was, or Iraq. ‘All around the camp, they are Kurdish mafia.’

Arian considered himself a mountain goat, more comfortable with the air at altitude than at sea level. Born in the Zagros Mountains in the west of Iran, his earliest memories are of family walks at weekends, learning to climb sheer rock faces and the perfect, still silence when he reached the top. Tracks were lined with rivas, or wild rhubarb, pomegranate and pistachio trees, which his mother would pick, carrying bagfuls back to make a stew with slow-cooked lamb that melted in his mouth. There were grottoes and springs gushing into reflective pools. Stories of brown bears making their way down from nearby mountain villages frequently circulated around his school, giving him nightmares. The call to prayer vibrated among the hilltops, punctuating each day with its soothing sounds. In many ways, his was a typical Iranian Kurdish family: faithful, devout members of Shia Islam and pillars of their local community.

But things were starting to change for Arian. He began watching movies, listening to music and talking to friends about the West, these ‘modern, Christian’ nations, keen to ‘learn and change and improve’. He desired that for himself and decided, after a brief period of atheism, that it was ‘better to have a belief than no belief’. He read the Bible and found its verses resonated. The first time he read ‘seek and you shall find’, a shiver ran up his spine. Arian felt he needed to begin a life beyond his tiny village.

A vast mountainous region stretching from south-eastern Turkey, to Iraq, northern Syria and on to north-western Iran, Kurdistan and its people have suffered decades of deep-rooted discrimination, denied their social, political, economic and cultural rights. Parents are not allowed to register their children with Kurdish names and use of the language in institutions, including schools, can result in prosecution.6 Civil society activists are frequently imprisoned, tortured and denied a fair trial. Some Iranian Kurds have faced the death penalty for expressing their beliefs.7

Following the 1979 Revolution in Iran, Ayatollah Khamenei declared jihad against the Kurdish people calling for autonomy. Ever since, there has been what the Kurdistan Peace and Development Society calls a ‘systematic genocidal campaign’, with tens of thousands killed in a sustained military operation.8 Kurds continue to call for representation and protection of their human rights and the creation of a recognised federal state.

On 16 September 2022 widespread protests broke out following the death of Mahsa Amini, a twenty-two-year-old Kurdish woman, arrested by the religious morality police for the way she wore her hijab. While the authorities said Mahsa died of a heart attack, eyewitnesses, including women who were held in police custody at the same time, reported that she had been severely beaten and later died in hospital as a result of her injuries.

Starting in her Kurdish homeland of Sanandaj in the north-west of Iran, Mahsa’s death sparked the largest protests the country had seen for more than a decade. Hundreds of thousands took to the streets, with defiant demonstrators removing and burning their hijabs in street bonfires and cutting their hair in protest.

Their actions were brutally repressed. Within the first six months, over 500 people were killed and more than 20,000 arrested. Human Rights Watch reported live ammunition fired into crowds and protesters beaten with batons.9 In Kurdistan, the regime unleashed alarming violence, with agents wielding Kalashnikov assault rifles firing live rounds, pellets and tear gas, sometimes directly into homes.

Seeing the protests, Arian felt acutely aware of his security. He was, he felt, an easy target: with his sleek, jet-black hair tied back in a ponytail, caramel skin and almond eyes, people often told him he looked more like a Mayan than a Kurd, ‘a person from the pyramid temples’.

His younger brother had recently married, and while he, too, had been engaged, it was an arranged marriage, not the romance of which he had always dreamed. Constrained and claustrophobic, the relationship had ended and Arian had piled himself into his studies in aerospace engineering, specialising in rocket propulsion and aerodynamics, his ambition to work with helicopters, aeroplanes, ‘anything that moves in the air’. He had always been bright and driven, particularly studious when it came to maths and physics. Now he saw his talents as a way out.

The day the protests came to his doorstep, he felt a tug towards them. This was the way to bring about change, to really fight for what you believe in. Compelled to see for himself, he dressed in black and ventured outside, standing at the side of the road and watching as thousands of people marched past with banners proclaiming ‘Women, Life, Freedom’.

He was, as he feared, a visible target. Within minutes, thirty armed police arrived on motorbikes, shooting rubber pellets at him. A dozen thugs grabbed him by the hair and wrestled him to the ground, beating, kicking, thrashing him until he could hardly breathe. He was left, curled up, foetal-like, on the pavement and slipping in and out of consciousness. ‘I could not open my eyes, or hear. My body was all black and blue and my face was covered with blood.’ Arian knew he needed to get out of Iran.

He spoke to a friend who had also been caught up in the protests. It was easy for them to find a smuggler: it was big business, with so many people sharing their experiences of repression, violence and the dream of a better life. They agreed they didn’t need to decide where they would go; they would simply travel over the border and keep moving until they could settle.

With help from his father and brother, Arian gathered together $10,000 cash and brought it to his friend’s smuggler, someone he felt he could trust: $5,000 to set up the journey, then another $5,000 to cross over to Greece and travel onwards. Their safety, they were told, was guaranteed. Within days he had said goodbye, knowing he might never see his family again, but certain he couldn’t stay.

Crossing the Turkish border by truck and arriving in the city of Van in the east of the country, Arian and his friend were passed on to another smuggler. Hours were spent waiting to connect with the next link in the chain, for money to be released, names crossed off lists and messages sent to facilitators further down the network.

From there to Greece over the river crossing of Edirne, then by boat and truck across Italy and on to France, the smugglers made the journey smooth. It was a well-oiled machine, with a broker, or ‘travel agent’, in Iran releasing money to smugglers each time he crossed a border. Whenever he arrived, a smuggler held up a phone to Arian’s ear to say his name, confirm he was there and that the money could be released. Sometimes an address would then be handed over or he, along with other members of the group, would be taken to a sparse, damp flat with sheetless mattresses on the floor to get a few hours’ sleep before the journey continued. More often there was nowhere to stay, nowhere to rest.

Separated from his friend, Arian sometimes travelled with new acquaintances he made along the way, but often he walked alone, slipping under barbed-wire fencing, navigating packs of dogs and sleeping under bridges with only his sodden coat to cover him. Once, when he fell asleep on a night bus, a woman left a half-eaten bar of chocolate on the seat next to him. It was the first time he had eaten in days.

By the time he reached northern France, Arian was so physically, mentally and emotionally exhausted that he considered trying to stay there. He asked around the camps about claiming asylum in France, but the only people who had information, he realised, were the smugglers. He hadn’t planned to go to the UK, but once he was in the camps, everybody said the same thing: ‘England, it’s better.’

It made sense. Arian speaks English, he has committed song lyrics by The Beatles to memory, he follows the Premier League football teams. The island beyond was the final destination. ‘After England, there is nowhere. You just try to finish the path.’ The camps were inhospitable, the system complex. France would never feel like home. He needed to keep moving.

Smugglers circulate freely and visibly in the camps of northern France, so it didn’t take long to find the man he needed to help him cross the Channel. Pasha, or the ‘big boss’ as Arian called him, was one of the more notorious smugglers: quick to reply to messages, organised and motivated. After several failed attempts in the preceding days, Pasha was determined to get his passengers moving.

Late the next evening, there was a ping on Arian’s phone. The message told him to make his way to a supermarket on the edge of Dunkirk, where he would be given the next set of instructions.

He did as he was told, nervously approaching a man speaking Kurdish in an aisle of the minimart. Tonight they would try again. Arian just needed to go to the bus depot close by and wait until Pasha’s passengers were called.

As night fell, the depot became a hive of activity, with over a hundred people gathering round. Arian spoke to a small group of Kurdish men busily checking their phones for any updates and discussing the weather conditions. They showed him an app called Windy, which detected the wind speeds, the wave heights and the temperatures in the water. ‘Anything over a half-metre wave is too much. Below ten knots [wind speed] is OK, no problem for the boat. Over twenty knots, you die.’

Three hours later, his moment arrived. ‘Passengers of Pasha, come!’ someone called, and Arian stepped forward, a plastic bag and tattered woolly hat in his hands. The group of passengers were separated into smaller units, told where to go, their turns staggered.

The small groups stayed close to their smuggler, told to walk in silence, no smoking, no light – nothing that would draw attention to them. Arian felt all ajumble: fearful, confused, hungry, cold and under immense stress. As he made his way along the muddy path, stumbling through woodland and over craggy peaks, he wondered if this attempt would fail like so many of the others or if today, finally, he was fated to succeed.

In spite of all he had endured, seeing the white cliffs from the Border Force boat was, Arian later told me, ‘like new air, like I could breathe again’.

2. SOS

The sea is calm to-night,

The tide is full, the moon lies fair

Upon the straits;—on the French coast, the lightGleams, and is gone; the cliffs of England stand,Glimmering and vast, out in the tranquil bay.

Come to the window, sweet is the night-air!Only, from the long line of sprayWhere the sea meets the moon-blanched land,

Listen! you hear the grating roar

Of pebbles which the waves draw back, and fling,At their return, up the high strand,

Begin, and cease, and then again begin,With tremulous cadence slow, and bring

The eternal note of sadness in.

Matthew Arnold, ‘Dover Beach’, 1851

Though Arian didn’t know it, a group of eagle-eyed onlookers were watching him arrive from the clifftops above the port. Among them was Bob Satchett, a gruff, rotund man in his late sixties with a pair of binoculars pressed to his face. Fishing trawlers, cruise liners, passenger ferries and container ships dotted the horizon, a string of tiny, twinkling lanterns in the Dover Strait beyond. Squinting through the mist, Bob could just make out a rescue boat chugging towards the quay below.

‘Busier today,’ he murmured to the four acquaintances seated beside him on fold-up camping chairs. Nobody spoke, only nodded slowly in agreement. Three identical pit bull terriers roamed around the overflowing bins nearby, cigarette butts buried beneath the frost.

The car park at Western Heights was quieter now that winter had set in and the volume of arrivals had slowed, but this group were the committed, the hardcore, armed with cans of Coke and filming equipment, settling in for a day of what they called ‘migrant spotting’.

After he retired five years ago, Bob used to come up here every day to walk his dog, to ‘get some peace and quiet’. He had lived in Dover all his life, went to school here, got married, had three kids. Decades of driving HGV lorries across borders, sitting in tedious queues at ports, too much time spent away from home, had taken its toll. His wife had left him and taken the children with her. He never really saw them now they had families of their own. This place, up on the westerly ridge, had become a sanctuary for him, a place he came to meet with friends, often going on for a pint or two at the local pub together once it opened.

On a clear day, Bob could see all the way to France from this vantage point, the soft silhouette undulating in the distance. Turning west, the turrets of Dover Castle rose skywards, its fortified walls still perfectly intact. Walking down the chalk path, he could go right up to the deep, sunken ditches, abandoned gun emplacements and former barracks.

The land here was steeped in history, both national and personal. It gave Bob a distinct sense of pride. Sometimes he would wander among the ivy-covered blast shelters and pillboxes, inspect the crumbling remnants of the gun battery, imagining what terror his grandfather and his great-grandfather must have endured. During the Napoleonic Wars, stretching all the way through the First and the Second World Wars, this had been the defensive frontline, designed to protect Britain from foreign invasion.

Now, though, the threats were out of his hands. He felt exposed, unsure who the newcomers were or why they were here. It was impossible to ignore it when it was down there, ‘staring you in the face’. No matter what the government did, the dinghies just kept coming.

Being among a group of like-minded people made Bob feel that bit safer. Sometimes Nigel Farage came up to Western Heights to record his pieces-to-camera. The leader of Reform UK – and, many would say, a major catalyst for Brexit – had made some of his most infamous comments on the clifftops here. What we were witnessing was, Farage told his captive audience, an ‘invasion’ not unlike other pivotal moments of our history.1

Bob was well acquainted with Farage – he was ‘not a mate, but someone you see around, every now and again’. Like ‘Nige’, watching the new arrivals coming in and being given the ‘royal treatment’ incensed him. Billions of pounds of imports and exports were going in and out of Dover, but locals weren’t reaping any of the rewards. If anything, they had become more marginalised. ‘You’ve got to look after your own first’ was a constant, tic-like refrain.

Once, not that long before – a couple of decades maybe – Dover had been a thriving industrial town, with many taking jobs at Buckland paper mill a few miles inland.2 Some of Bob’s friends had worked as wardens at the borstal at Western Heights, but then that closed down in 2015, and with it went the jobs. Nothing had come along to replace them, other than the odd bit of work for shipping companies and selling fishing tackle. Rates of debt, homelessness, domestic violence and child poverty had spiked.3

Working people needed someone who understood them, who knew the area and could speak up for them. Not only that: they needed someone who could stand shoulder-to-shoulder with strong leaders like Donald Trump and not be cowered. Bob admired that, while Nige had power and clout, he’d kept his feet on the ground.

There were always reporters around Western Heights now, cameramen hauling tripods round the corner. Journalists made him suspicious; you never knew who you could trust nowadays. Bob didn’t need to watch the news or read the papers. He could see what was happening with his own eyes. What he couldn’t get his head around was why the government didn’t just do what they’d promised and stop those bloody boats.

Pushing them back in the Dover Strait wasn’t a bad idea, Bob felt, but ‘they definitely shouldn’t be pulling them in’. Sometimes the migrants were making beach landings then ‘scuttling off’. They weren’t even being apprehended.

The vast majority of new arrivals – the ones he saw – were being taxied in by the Border Force and the Royal National Lifeboat Institution, the RNLI. He couldn’t understand why those agencies did it, why they were doing ‘such a disservice to patriots’. Neither of those were the real traitors, though. That charge lay with the agency Bob believed was not only helping migrants but encouraging them to make the crossing: ‘them up there in their ivory towers, the coastguard’.

In the watchtower located to the west of Dover harbour’s inner walls, phones were ringing insistently. Radios spurted, crackled and gurgled to life. Heavy-duty boots clanged up and down the metal steps overhead.

‘Another one coming in,’ Tony announced, setting down his cup of tea, zipping up his royal-blue overalls and striding down the gangway towards the Border Force boat below. There was never a dull moment in this job. It was just after twelve, but already it had been designated a ‘red day’, with tides and weather increasing the chance of boat crossings. The red cross on the whiteboard inside the lookout tower served as a warning to Tony and his crew: they had better be prepared.

Outside, the quay was flooded with long-lens cameras, photographers jostling for position. Teenagers with buzz cuts, drafted in from the Navy to support the coastguard with logistics, wandered around looking confused. Towards the top of the gangway, chain-smoking coach drivers waited to shuttle new arrivals between the car park and the compound a couple of hundred metres away, where the process of claiming asylum would begin.

As the cutter docked, a stream of stumbling bodies made their way up the metal walkway, sodden slate-grey blankets wrapped round their shoulders, grasping the rail to steady their trembling legs. Clambering aboard the buses, they collapsed down into worn seats, sitting staring out of the window, watching as the dinghy they had crossed in was spray-painted with a number and punctured.

It was unusual for Tony to be on the quay that day. He spent most of his time up in the control room at Langdon Battery overlooking the port. It was calmer up there, easier for the coastguard to see what was going on, to manage traffic in the Dover Strait. It was no mean feat: the Channel was the busiest shipping lane in the world. Attempting the crossing by small boat was regularly likened to crossing the M25 at rush hour on foot.

He and his colleagues enjoyed the camaraderie up there. They would joke that the Battery looked like a spaceship, its roof covered by thick vegetation, its windows like a cockpit looking out on to the eastern arm of Dover harbour.

Sometimes they got calls from Beachy Head, urgent warnings of a different kind of crisis. They occasionally saw Channel swimmers, too, embarking on a voyage across soupy, silty water. Tony didn’t understand it: people were risking their lives to reach these shores, dying in dark waters. To him, crossing the Strait wasn’t about leisure, it was about survival.

The work had changed since the boats started coming in. During a particularly busy shift, Tony and his team might receive thirty distress calls from the same dinghy. There might be forty small boats in British waters at once, or more, each with seventy, eighty, even a hundred people on board. It was difficult to keep tabs on them all.

Tony was a seafarer, a mariner, who couldn’t picture himself doing any other work. If you cut him open, there’d be ‘saltwater in these veins’. He’d grown up that way. At weekends, he’d go out fishing with his dad on the Jurassic coast, tying the bait, learning to cast the net, then taking the trawl home to cook up for dinner. He hadn’t enjoyed school particularly, ‘too much sitting around’. As soon as he could, he started work, following in his dad’s footsteps, like salmon up a stream.

A decade in, despite many attempts to make a decent living, Tony saw the ‘writing was on the wall’ for the fishing industry. Shortly after the birth of his first child, he moved his family up the coastline. It was a leap of faith; he didn’t know if he’d be able to earn enough to support them.

It hadn’t always been smooth, but over the years he’d worked his way up through the coastguarding ranks, feeling challenged, motivated, a vital member of the ‘blue-light family’. His leadership style was outspoken, even slightly bombastic, but he had the allure of charisma, which kept his colleagues onside. When it was busy he’d tell his team it was ‘all hands on deck’, and he lived up to it. Tony was always the last to leave at the end of a shift.

Now, though, instead of answering 999 calls from locals and tourists, his job had become ‘massively political’. Hours were spent preparing for a high-profile visit from the prime minister, the home secretary, whoever it might be. He would have to give them the grand tour of the Battery, show them the tracking systems and how the new surveillance technology worked. There was a lot of hand-shaking, head-bobbing, smiling. Often cameras snapped distractingly.

What he couldn’t tell those politicians was just how overstretched the coastguard was, how under-resourced. He had been working twenty-hour shifts, often with no breaks. A few hours’ sleep, then back to it. The pace was relentless. They were finding it difficult to recruit people. Salaries were poor, the nature of the work physically and emotionally taxing.

He had struggled at times himself. Once, he had carried an unconscious toddler from a dinghy, her limbs floppy and her mother inconsolable. Running towards the medical facility, he hadn’t known what to say, how to even communicate. An interpreter couldn’t be found. He didn’t even know if the child was breathing. The young girl was severely hypothermic, but she survived. Those aren’t the kind of images you can forget; flashbacks still came to him frequently.

The previous summer had been a particular low point. With nowhere to put new arrivals, tents had been erected on the quayside. Hundreds of traumatised people were forced to sleep on buses in the car park.4 For days, Tony and his team had worked round the clock, trying to get clothes, blankets and bottles of water to the bewildered newcomers. At that time, the area was open to the public and visible from Western Heights overlooking the jetty. They had faced torrents of abuse from members of the public while they carried out their work.

As the volume of new arrivals increased, so did the scrutiny. Tony had been pictured helping an elderly man as he limped up the gangway, bent double, badly injured. He had been lambasted by the right, but you couldn’t win on the left either. They were never seen to be doing enough. It often felt like a no-win situation.

Sometimes the pressure made his team fractious, snapping at each other. Support was on offer, but it was more rounds of tea and a biscuit than talking about what was on your mind. Coastguards didn’t tend to be the ‘soft and fluffy type’ – they just needed to blow off steam and move on.

All he knew was that he and his team had a job to do. No matter how busy they were, they could never ‘play roulette with people’s lives’. Whenever they received a mayday call they had to act on it, jumping into gear to assess the level of need, the numbers on board, whether there were casualties. They needed to pull together all their resources, to coordinate and put an effective plan in place. While the coastguard didn’t have its own rescue vessels, it could call on the Border Force and the RNLI, and they could task a helicopter, but only if they had enough information.

Sometimes a phone call from a dinghy might be just twenty seconds long, or it was inaudible, or the English was so broken it was incomprehensible. At other times, migrants withheld their locations. The smugglers told them they had to; they couldn’t risk their details being traced back to the passengers’ phones. What was the coastguard team supposed to do then? They had nothing to go on.

Tony had the sense that those making the calls were often speaking from scripts. The boat was sinking. There were women and children on board. No lifejackets, that sort of thing. All emergencies started to sound the same. He didn’t want to appear flippant – none of his team came in with the intention of letting people die – but in extremely challenging circumstances, mistakes could happen.

One incident in particular played on his mind. The coastguard was under investigation following a major disaster in the Channel several months before. Investigators had got hold of call logs, where it was all laid out.

On 24 November 2021, a passenger had called the French authorities to alert them that he and thirty-one other people were on board a sinking boat. ‘Please, please, we need help,’ the caller urged. Screams for mercy could be heard in the background. ‘You are in English waters, sir,’ the French coastguard responded, before hanging up.5

In the Dover coastguard control room, two members of staff, including one who was still a trainee, attempted to phone the passenger back, but they received a French dial tone. They left it, concluding, after much back-and-forth with the French coastguard, that the boat was not their responsibility as it was likely still in their waters.6

Twelve hours later, at around 2 p.m., a French fisherman spotted bodies in the water. All but two of the passengers had drowned, died of exposure or remained missing. Among the dead were twenty-one men, seven women, including one who was pregnant, and three children. It was the worst maritime disaster in the Channel for over forty years.

In the aftermath of the incident, I was put in contact with dozens of relatives and friends who had lost their loved ones that night. ‘Please [can you] help us meet with the UN?,’ one man messaged late one evening, desperately seeking answers. Another sent me screengrabs of the last contact he had had with his brother. ‘He cannot be gone,’ he typed.

At a vigil in Parliament Square to commemorate those who had died, a grief-stricken brother took the microphone.7 ‘I want to find out who was negligent,’ he told mourners. ‘The British and the French, they do nothing. They failed them and left them to drown. Now we hear nothing.’

Among the most devastating stories I heard was from Mustafa, whose son Zanyar had gone missing that night.8 A senior commander for the Kurdish Peshmerga, Mustafa left work early to speak to me, explaining that he now had two full-time jobs: one was in the military forces, the other was seeking justice for his son.

I was struck by Mustafa’s eyes, or perhaps what was behind them. He appeared hollowed out, his grief raw and all-consuming. At certain points, when he described Zanyar or the powerlessness he and his wife felt when faced with the heft of the UK and French authorities, Mustafa could contain his pain no longer and he broke down and sobbed.

On 24 November 2021, Mustafa had spoken on the phone to his son’s smuggler, who confirmed that Zanyar had arrived safely and requested immediate payment for the crossing. Mustafa’s wife went out to buy sweets for the village, going door-to-door to tell them her son had arrived in the UK. The journey, which had caused her so many sleepless nights, was finally over. Days later, still unable to reach Zanyar after multiple attempts, they began to worry. When news of the shipwreck reached Mustafa, he said it felt like ‘a horror movie, like every parent’s worst nightmare’.

As we came towards the end of an emotionally charged four hours, Mustafa appeared reluctant to let me go, still struggling to make sense of it all. Why, he needed to know, had they heard nothing from the UK authorities? Why were they being treated with such utter disdain?

The atmosphere at Langdon Battery hung heavy in the days that followed. Tony and his team were being called in for questioning, pressed about what had gone so badly wrong. It emerged slowly, painfully, the truth eked out over days of interviews.9