2,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: BookRix

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

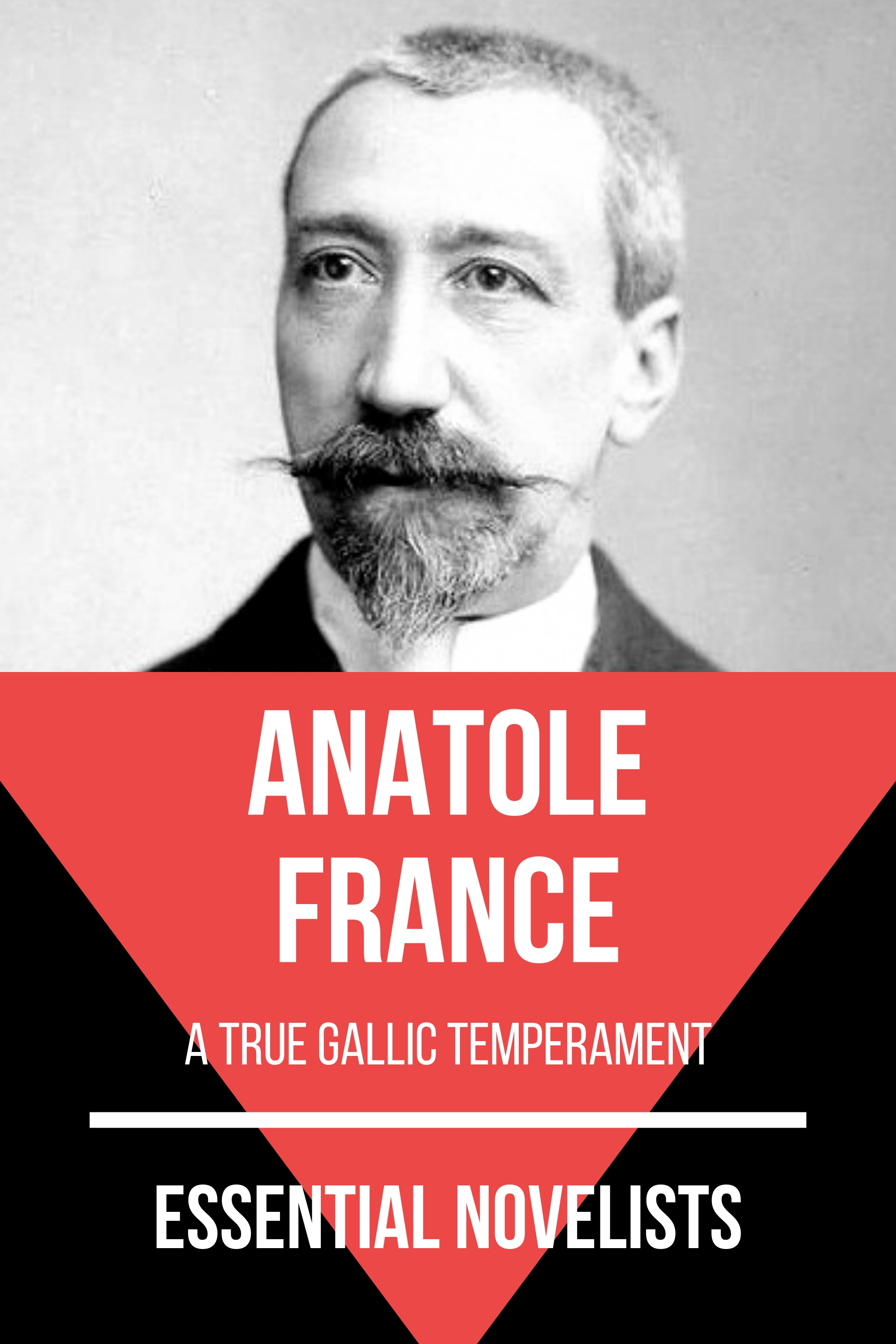

Anatole France began his career as a poet and a journalist. Le Parnasse Contemporain published one of his poems, La Part de Madeleine. He sat on the committee which was in charge of the third Parnasse Contemporain compilation. He moved Paul Verlaine and Mallarmé aside of this Parnasse. As a journalist, from 1867, he wrote a lot of articles and notices. He became famous with the novel Le Crime de Sylvestre Bonnard. Its protagonist, skeptical old scholar Sylvester Bonnard, embodied France's own personality. The novel was praised for its elegant prose and won him a prize from the French Academy. Masterful and poignant blending of religious and occult mysticism. Awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1921 "in recognition of his brilliant literary achievements, characterized as they are by a nobility of style, a profound human sympathy, grace, and a true Gallic temperament." Anatole France began his career as a poet and a journalist. In 1922, France's entire works were put on the Prohibited Books Index of the Roman Catholic Church.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Balthasar

BookRix GmbH & Co. KG81371 MunichBalthasar

By Anatole France

I

In those days Balthasar, whom the Greeks called Saracin, reigned in Ethiopia. He was black, but comely of countenance. He had a simple soul and a generous heart.

The third year of his reign, which was the twenty-second of his age, he left his dominions on a visit to Balkis, Queen of Sheba. The mage Sembobitis and the eunuch Menkera accompanied him. He had in his train seventy-five camels bearing cinnamon, myrrh, gold dust, and elephants' tusks.

As they rode, Sembobitis instructed him in the influences of the planets, as well as in the virtues of precious stones, and Menkera sang to him canticles from the sacred mysteries. He paid but little heed to them, but amused himself instead watching the jackals with their ears pricked up, sitting erect on the edge of the desert.

At last, after a march of twelve days, Balthasar became conscious of the fragrance of roses, and very soon they saw the gardens that surround the city of Sheba. On their way they passed young girls dancing under pomegranate trees in full bloom.

"The dance," said Sembobitis the mage, "is a prayer."

"One could sell these women for a great price," said Menkera the eunuch.

As they entered the city they were amazed at the extent of the sheds and warehouses and workshops that lay before them, and also at the immense quantities of merchandise with which these were piled.

For a long time they walked through streets thronged with chariots, street porters, donkeys and donkey-drivers, until all at once the marble walls, the purple awnings and the gold cupolas of the palace of Balkis, lay spread out before them.

The Queen of Sheba received them in a courtyard cooled by jets of perfumed water which fell with a tinkling cadence like a shower of pearls.

Smiling, she stood before them in a jewelled robe.

At sight of her Balthasar was greatly troubled.

She seemed to him lovelier than a dream and more beautiful than desire.

"My lord," and Sembobitis spoke under his breath, "remember to conclude a good commercial treaty with the queen."

"Have a care, my lord," Menkera added. "It is said she employs magic with which to gain the love of men."

Then, having prostrated themselves, the mage and the eunuch retired.

Balthasar, left alone with Balkis, tried to speak; he opened his mouth but he could not utter a word. He said to himself, "The queen will be angered at my silence."

But the queen still smiled and looked not at all angry. She was the first to speak with a voice sweeter than the sweetest music.

"Be welcome, and sit down at my side." And with a slender finger like a ray of white light she pointed to the purple cushions on the ground. Balthasar sat down, gave a great sigh, and grasping a cushion in each hand he cried hastily:

"Madam, I would these two cushions were two giants, your enemies; I would wring their necks."

And as he spoke he clutched the cushions with such violence in his hands that the delicate stuff cracked and out flew a cloud of snow-white down. One of the tiny feathers swayed a moment in the air and then alighted on the bosom of the queen.

"My lord Balthasar," Balkis said, blushing; "why do you wish to kill giants?"

"Because I love you," said Balthasar.

"Tell me," Balkis asked, "is the water good in the wells of your capital?"

"Yes," Balthasar replied in some surprise.

"I am also curious to know," Balkis continued, "how a dry conserve of fruit is made in Ethiopia?"

The king did not know what to answer.

"Now please tell me, please," she urged.

Whereupon with a mighty effort of memory he tried to describe how Ethiopian cooks preserve quinces in honey. But she did not listen. And suddenly, she interrupted him.

"My lord, it is said that you love your neighbour, Queen Candace. Is she more beautiful than I am? Do not deceive me."

"More beautiful than you, madam," Balthasar cried as he fell at the feet of Balkis, "how could that possibly be?"

"Well then, her eyes? her mouth, her colour? her throat?" the queen continued.

With his arms outstretched towards her, Balthasar cried:

"Give me but the little feather that has fallen on your neck and in return you shall have half my kingdom as well as the wise Sembobitis and Menkera the eunuch."

But she rose and fled with a ripple of clear laughter.

When the mage and the eunuch returned they found their master plunged deep in thought which was not his custom.

"My lord!" asked Sembobitis, "have you concluded a good commercial treaty?"

That day Balthasar supped with the Queen of Sheba, and drank the wine of the palm-tree.

"It is true, then," said Balkis as they supped together, "that Queen Candace is not so beautiful as I?"

"Queen Candace is black," replied Balthasar.

Balkis looked expressively at Balthasar.

"One may be black and yet not ill-looking," she said.

"Balkis!" cried the king.

He said no more, but seized her in his arms, and the head of the queen sank back under the pressure of his lips. But he saw that she was weeping. Thereupon he spoke to her in the low, caressing tones that nurses use to their nurslings. He called her his little blossom and his little star.

"Why do you weep?" he asked. "And what must one do to dry your tears? If you have a desire tell me and it shall be fulfilled."

She ceased weeping, but she was sunk deep in thought. He implored her a long time to tell him her desire. And at last she spoke.

"I wish to know fear."

And as Balthasar did not seem to understand, she explained to him that for a long time past she had greatly longed to face some unknown danger, but she could not, for the men and gods of Sheba watched over her.

"And yet," she added with a sigh, "during the night I long to feel the delicious chill of terror penetrate my flesh. To have my hair stand up on my head with horror. O! it would be such a joy to be afraid!"

She twined her arms about the neck of the dusky king, and said with the voice of a pleading child:

"Night has come. Let us go through the town in disguise. Are you willing?"

He agreed. She ran to the window at once and looked through the lattice into the square below.

"A beggar is lying against the palace wall. Give him your garments and ask him in exchange for his camel-hair turban and the coarse cloth girt about his loins. Be quick and I will dress myself."

And she ran out of the banqueting-hall joyfully clapping her hands one against the other.

Balthasar took off his linen tunic embroidered with gold and girded himself with the skirt of the beggar. It gave him the look of a real slave. The queen soon reappeared dressed in the blue seamless garment of the women who work in the fields.

"Come!" she said.

And she dragged Balthasar along the narrow corridors towards a little door which opened on the fields.

II

The night was dark, and in the darkness of the night Balkis looked very small.

She led Balthasar to one of the taverns where wastrels and street porters foregathered along with prostitutes. The two sat down at a table and saw through the foul air by the light of a fetid lamp, unclean human brutes attack each other with fists and knives for a woman or a cup of fermented liquor, while others with clenched fists snored under the tables. The tavern-keeper, lying on a pile of sacking, watched the drunken brawlers with a prudent eye. Balkis, having seen some salt fish hanging from the rafters of the ceiling, said to her companion:

"I much wish to eat one of these fish with pounded onions."

Balthasar gave the order. When she had eaten he discovered that he had forgotten to bring money. It gave him no concern, for he thought that he could slip out with her without paying the reckoning. But the tavern-keeper barred their way, calling them a vile slave and a worthless she-ass. Balthasar struck him to the ground with a blow of his fist. Whereupon some of the drinkers drew their knives and flung themselves on the two strangers. But the black man, seizing an enormous pestle used to pound Egyptian onions, knocked down two of his assailants and forced the others back. And all the while he was conscious of the warmth of Balkis' body as she cowered close to him; it was this which made him invincible.

The tavern-keeper's friends, not daring to approach again, flung at him from the end of the pot-house jars of oil, pewter vessels, burning lamps, and even the huge bronze cauldron in which a whole sheep was stewing. This cauldron fell with a horrible crash on Balthasar's head and split his skull. For a moment he stood as if dazed, and then summoning all his strength he flung the cauldron back with such force that its weight was increased tenfold. The shock of the hurtling metal was mingled with indescribable roars and death rattles. Profiting by the terror of the survivors, and fearing that Balkis might be injured, he seized her in his arms and fled with her through the silence and darkness of the lonely byways. The stillness of night enveloped the earth, and the fugitives heard the clamour of the women and the carousers, who pursued them at haphazard, die away in the darkness. Soon they heard nothing more than the sound of dripping blood as it fell from the brow of Balthasar on the breast of Balkis.

"I love you," the queen murmured.

And by the light of the moon as it emerged from behind a cloud the king saw the white and liquid radiance of her half-closed eyes. They descended the dry bed of a stream, and suddenly Balthasar's foot slipped on the moss and they fell together locked in each other's embrace. They seemed to sink forever into a delicious void, and the world of the living ceased to exist for them. They were still plunged in the enchanting forgetfulness of time, space and separate existence, when at daybreak the gazelles came to drink out of the hollows among the stones.

At that moment a passing band of brigands discovered the two lovers lying on the moss.

"They are poor," they said, "but we shall sell them for a great price, for they are so young and beautiful."

Upon which they surrounded them, and having bound them they tied them to the tail of an ass and proceeded on their way.

The black man so bound threatened the brigands with death. But Balkis, who shivered in the cool, fresh air of the morning, only smiled, as if at something unseen.

They tramped through frightful solitudes until the heat of mid-day made itself felt. The sun was already high when the brigands unbound their prisoners, and, letting them sit in the shade of a rock, threw them some mouldy bread which Balthasar disdained to touch but which Balkis ate greedily.

She laughed. And when the brigand chief asked why she laughed, she replied:

"I laugh at the thought that I shall have you all hanged."

"Indeed!" cried the chief, "a curious assertion in the mouth of a scullery wench like you, my love! Doubtless you will hang us all by the aid of that blackamoor gallant of yours?"

At this insult Balthasar flew into a fearful rage, and he flung himself on the brigand and clutched his neck with such violence that he nearly strangled him.

But the other drew his knife and plunged it into his body to the very hilt. The poor king rolled to earth, and as he turned on Balkis a dying glance his sight faded.

III

At this moment was heard an uproar of men, horses and weapons, and Balkis recognised her trusty Abner who had come at the head of her guards to rescue his queen, of whose mysterious disappearance he had heard during the night.

Three times he prostrated himself at the feet of Balkis, and ordered the litter to advance which had been prepared to receive her. In the meantime the guards bound the hands of the brigands. The queen turned towards the chief and said gently: "You cannot accuse me of having made you an idle promise, my friend, when I said you would be hanged."

The mage Sembobitis and Menkera the eunuch, who stood beside Abner, gave utterance to terrible cries when they saw their king lying motionless on the ground with a knife in his stomach. They raised him with great care. Sembobitis, who was highly versed in the science of medicine, saw that he still breathed. He applied a temporary bandage while Menkera wiped the foam from the king's lips. Then they bound him to a horse and led him gently to the palace of the queen.

For fifteen days Balthasar lay in the agonies of delirium. He raved without ceasing of the steaming cauldron and the moss in the ravine, and he incessantly cried aloud for Balkis. At last, on the sixteenth day, he opened his eyes and saw at his bedside Sembobitis and Menkera, but he did not see the queen.

"Where is she? What is she doing?"

"My lord," replied Menkera, "she is closeted with the King of Comagena."

"They are doubtless agreeing to an exchange of merchandise," added the sage Sembobitis.

"But be not so disturbed, my lord, or you will redouble your fever."

"I must see her," cried Balthasar. And he flew towards the apartments of the queen, and neither the sage nor the eunuch could restrain him. On nearing the bedchamber he beheld the King of Comagena come forth covered with gold and glittering like the sun. Balkis, smiling and with eyes closed, lay on a purple couch.

"My Balkis, my Balkis!" cried Balthasar.

She did not even turn her head but seemed to prolong a dream.

Balthasar approached and took her hand which she rudely snatched away.

"What do you want?" she said.

"Do you ask?" the black king answered, and burst into tears.

She turned on him her hard, calm eyes.

Then he realised that she had forgotten everything, and he reminded her of the night of the stream.

"In truth, my lord," said she, "I do not know to what you refer. The wine of the palm does not agree with you. You must have dreamed."

"What," cried the unhappy king, wringing his hands, "your kisses, and the knife which has left its mark on me, are these dreams?"

She rose; the jewels on her robe made a sound as of hail and flashed forth lightnings.

"My lord," she said, "it is the hour my council assembles. I have not the leisure to interpret the dreams of your suffering brain. Take some repose. Farewell."

Balthasar felt himself sinking, but with a supreme effort not to betray his weakness to this wicked woman, he ran to his room where he fell in a swoon and his wound re-opened.

IV

For three weeks he remained unconscious and as one dead, but having on the twenty-second day recovered his senses, he seized the hand of Sembobitis, who, with Menkera, watched over him, and cried, weeping:

"O, my friends, how happy you are, one to be old and the other the same as old. But no! there is no happiness on earth, everything is bad, for love is evil and Balkis is wicked."

"Wisdom confers happiness," replied Sembobitis.

"I will try it," said Balthasar. "But let us depart at once for Ethiopia." And as he had lost all he loved he resolved to consecrate himself to wisdom and to become a mage. If this decision gave him no especial pleasure it at least restored to him something of tranquillity. Every evening, seated on the terrace of his palace in company with the sage Sembobitis and Menkera the eunuch, he gazed at the palm-trees standing motionless against the horizon, or watched the crocodiles by the light of the moon float down the Nile like trunks of trees.

"One never wearies of admiring the beauties of Nature," said Sembobitis.

"Doubtless," said Balthasar, "but there are other things in Nature more beautiful than even the palm-trees and crocodiles."

This he said thinking of Balkis. But Sembobitis, who was old, said:

"There is of course the phenomenon of the rising of the Nile which I have explained. Man is created to understand."

"He is created to love," replied Balthasar sighing. "There are things which cannot be explained."

"And what may those be?" asked Sembobitis.

"A woman's treason," the king replied.

Balthasar, however, having decided to become a mage, had a tower built from the summit of which might be discerned many kingdoms and the infinite spaces of Heaven. The tower was constructed of brick and rose high above all other towers. It took no less than two years to build, and Balthasar expended in its construction the entire treasure of the king, his father. Every night he climbed to the top of this tower and there he studied the heavens under the guidance of the sage Sembobitis.

"The constellations of the heavens disclose our destiny," said Sembobitis.

And he replied:

"It must be admitted nevertheless that these signs are obscure. But while I study them I forget Balkis, and that is a great boon."

And among truths most useful to know, the mage taught that the stars are fixed like nails in the arch of the sky, and that there are five planets, namely: Bel, Merodach, and Nebo, which are male, while Sin and Mylitta are female.

"Silver," he further explained, "corresponds to Sin, which is the moon, iron to Merodach, and tin to Bel."

And the worthy Balthasar answered: "Such is the kind of knowledge I wish to acquire. While I study astronomy I think neither of Balkis nor anything else on earth. The sciences are beneficent; they keep men from thinking. Teach me the knowledge, Sembobitis, which destroys all feeling in men and I will raise you to great honour among my people."

This was the reason that Sembobitis taught the king wisdom.

He taught him the power of incantation, according to the principles of Astrampsychos, Gobryas and Pazatas. And the more Balthasar studied the twelve houses of the sun, the less he thought of Balkis, and Menkera, observing this, was filled with a great joy.

"Acknowledge, my lord, that Queen Balkis under her golden robes has little cloven feet like a goat's."

"Who ever told you such nonsense?" asked the King.

"My lord, it is the common report both in Sheba and Ethiopia," replied the eunuch. "It is universally said that Queen Balkis has a shaggy leg and a foot made of two black horns."

Balthasar shrugged his shoulders. He knew that the legs and feet of Balkis were like the legs and feet of all other women and perfect in their beauty. And yet the mere idea spoiled the remembrance of her whom he had so greatly loved. He felt a grievance against Balkis that her beauty was not without blemish in the imagination of those who knew nothing about it. At the thought that he had possessed a woman who, though in reality perfectly formed, passed as a monstrosity, he was seized with such a sense of repugnance that he had no further desire to see Balkis again. Balthasar had a simple soul, but love is a very complex emotion.

From that day on the king made great progress both in magic and astrology. He studied the conjunction of the stars with extreme care, and he drew horoscopes with an accuracy equal to that of Sembobitis himself.

"Sembobitis," he asked, "are you willing to answer with your head for the truth of my horoscopes?"

And the sage Sembobitis replied:

"My lord, science is infallible, but the learned often err."

Balthasar was endowed with fine natural sense. He said:

"Only that which is true is divine, and what is divine is hidden from us. In vain we search for truth. And yet I have discovered a new star in the sky. It is a beautiful star, and it seems alive; and when it sparkles it looks like a celestial eye that blinks gently. I seem to hear it call to me. Happy, happy, happy is he who is born under this star. See, Sembobitis, how this charming and splendid star looks at us."

But Sembobitis did not see the star because he would not see it. Wise and old, he did not like novelties.

And alone in the silence of night Balthasar repeated: "Happy, happy, happy he who is born under this star."