Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Papillote Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

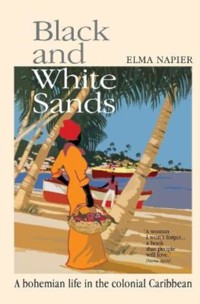

- "A woman I won't forget ... a book that people will love." Diana Athill, Jean Rhys' publisher and award-winning biographer. - "My aunt's love of Dominica and its people is as freshly painted as if it happened yesterday." Katie Fforde, novelist. - Elma Napier's remarkable memoir chronicles her love affair with the wild Caribbean island of Dominica. It began in 1932 when she turned her back on London's high society to build a home in Calibishie, a remote village on Dominica's north coast. There are tales of literary house parties, of war and death, smugglers and servants and, above all, of stories inspired by her political life as the only woman in a colonial parliament. She writes deftly about the island's turbulent landscapes and her curiosity about the lives and culture of its people. Elma Napier was born in Scotland in 1892, the daughter of Sir William Gordon Cumming, who was accused of cheating while playing cards with the Prince of Wales. After living in Australia for nine years, Napier settled in Dominica with her second husband in 1932. She became the first woman to sit in any West Indian parliament. Apart from Black and White Sands (written in 1962), she wrote two novels and two memoirs of her early life. She died in Dominica in 1973.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 342

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published in Great Britain in 2009

Reprinted 2014

Reprinted 2015

© 2009 for the estate of Elma Napier

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Typeset in Sabon

Design by Andy Dark

Cover design by Andy Dark, adapted from a vintage Royal Mail line poster

by Kenneth Shoesmith

ISBN: 978 0 9532224 4 5

Papillote Press

23 Rozel Road

London SW4 0EY

United Kingdom

www.papillotepress.co.uk

and Trafalgar, Dominica

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The publisher would like to thank the family of Elma Napier, in particular Patricia Honychurch and Lennox Honychurch for their permission to publish the book, and for their unstinting support, wealth of knowledge and generosity; also many thanks to Michael and Josette Napier for their help, in particular for the loan of photographs, and to Alan Napier likewise. Thanks, too, to Margaret Busby, for the index. All photographs, unless otherwise credited, are courtesy of the Honychurch and Napier families.

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Nothing So Blue (1927)

Duet In Discord (1936)

A Flying Fish Whispered (1938, republished by Peepal Tree Press, 2009)

Youth Is A Blunder (1948)

Winter Is In July (1949)

Contents

Before Dominica: a portrait of Elma Napier

1 Falling in love

2 Dreaming the dream

3 Of mud and cockroaches

4 Building Pointe Baptiste

5 A new design for living

6 Forest and river

7 A taste of colonial politics

8 War and death

9 “Must I wear a hat?”

10 Shortages and smugglers

11 Deck class to Barbados

12 Manners, migration and bananas

13 Battle of the transinsular road

14 The sea for company

Dominica

Map of Dominica showing the main places mentioned in this book, parish boundaries and the extent of motorable roads on the island before 1956. The parishes of St. Andrew and St. David made up the constituency of Lennox and Elma Napier in the Legislative Council.

Before Dominica: a portrait of Elma Napier

Elma Gordon Cumming as a child in Scotland in 1899.

“I have made of my life a curious patchwork,” wrote Elma Napier. Indeed, by the time she arrived in Dominica with her husband and children in 1932, this talented and fearless woman had spent her childhood on a grand estate in the Scottish highlands, lived in the Australian outback, visited the South Seas, and danced with the future Edward VIII. More significantly, she had emerged from two scandals: the social ostracism of her aristocratic father from the Edwardian court, and her own adultery and divorce. Such emotional upheavals she never mentions in Black and White Sands but they shaped her life, and, ultimately, brought her to the wild tropical shores of Dominica where she lived until her death in 1973 at the age of 81.

Elma Napier was born in Scotland, the eldest child of Sir William Gordon Cumming, whose family had owned “half of Scotland”, including the house that later became Gordonstoun school. But in 1890, two years before her birth, Sir William was accused of cheating during a baccarat game with the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII). This famously became known as the Tranby Croft affair. Sir William sued for defamation, and lost. He also lost his place in high society, and was, for ever after, shunned. “No one spoke to him,” wrote his daughter of her father’s disgrace.

But Elma was to suffer more from being born a girl (“It was understood in our house that boys were superior beings”) than from social rejection. She was a teenager when she realised her function was to make a brilliant marriage and so help rehabilitate the family. Her first memoir, Youth is a Blunder, of her early years, evokes what she called the “casual cruelty of childhood” often confined to a lonely existence with governesses (and 30 indoor servants), and only leavened by her love for exploring moors, forest and sea. She felt disconnected to her background, wanting to “run like a hunted hare” because, as she said, she felt that she “heard a different drummer”.

Family group at Hopeman House, Morayshire, Scotland, in 1927. Elma is in the front, with daughter Patricia on her knee. Back row: left, Sir William Gordon Cumming (father) and Alastair (brother). Middle row (left to right): Betty (sister-in-law) with her daughter Josephine; Cecily (sister), Daphne (daughter) and Roly (brother).

Then, at 18, she fell in love with a married man. When her parents found out, her mother told her “no decent man will marry you now”. But her mother was wrong, because a year later, she gratefully married Maurice Gibbs, an upper-class Englishman with global business connections. For nine years the couple lived in Australia, which she loved for its freedom and landscape, for a time on a sheep station exploring by car, horse and on foot the continent’s ferocious environment. Even so, she felt constrained by wifely duties.

Then she met Lennox Napier. He was also English, and also a businessman, but he had progressive ideas and had lived among the artists of post-Gauguin Tahiti: he introduced her to books and paintings and “the world that reads the New Statesman”. At first, as she wrote, she “had soft-pedalled this invitation to the waltz” but their relationship deepened. And in this partnership she found an answer to her restlessness. But it was at a high cost. In the wake of her divorce, she forfeited the two children of that marriage into the care of their father. (Ronald became an RAF pilot and was killed in action in 1942, while daughter Daphne would eventually rejoin her mother and, aged 20, accompany the Napiers to their new beginning in Dominica.) Elma and Lennox married in 1924.

The couple had “discovered” Dominica on a Caribbean cruise – taken on account of Lennox’s fragile health – and “fell in love at first sight, an infatuation without tangible rhyme or reason, yet no more irrational than any other falling in love”. At that time, it was dismally poor, sunk in colonial neglect. Indeed, some historians have argued that the small islands of the Caribbean had remained essentially unchanged since the end of slavery. But as Elma Napier evokes in Black and White Sands, her memoir of her life on the island, this was a society characterised by a self-sufficient peasantry, free to work the land and sea, unhindered by authority, and possessing a rich Creole culture. Peasant lives changed little until, after the shortages and dramas of the war years, post-war reforms brought roads, universal suffrage and some redistribution of land to this mountainous and dazzlingly green island.

Elma and Lennox Napier both played a part in these changes, in the politics of their adopted island. They may have been upper-class bohemians — complete with servants, but they were not lotus-eaters, nor, indeed, were they like the sybaritic settlers of that more famous part of empire, Kenya’s Happy Valley. Both became, at different times, members of the colony’s Legislative Council, Elma being the first woman to sit in a Caribbean parliament. Many years later this achievement was celebrated on a Dominican stamp that bears her image.

The Napiers, with their two small children, Patricia (Pat) and Michael, settled about as far away as was possible from the island’s capital Roseau. They lived in the north-coast village of Calibishie, building their house, Pointe Baptiste, on a cliff between two beaches – one of black sand, the other of white sand, and hence the title of this book. While they were certainly the “Sir” and “Madame” of the Big House, and ordered crystallised fruit and pâté from Harrods, they had different horizons from the rest of Dominica’s small white population – mainly colonial service officials whose wives wore gloves for tea parties, and played tennis at the all-white club.

Captain Lennox Napier during the first world war, with his pet lion cub, at a field hospital in France while recovering from his wounds. He married Elma Napier in 1924.

Elma Napier did not do that: with upper-class élan, she swam in the nude, walked alone along forest trails and endured long horseback rides to remote villages in tropical downpours. While the other wives baked cakes and gossiped about the servants, Elma wrote articles for the Manchester Guardian, talked to men about politics and learned about the landscape and culture of her adopted island.

Elma Napier

The latter was very important to her. “I would rather be an explorer to see round the next corner than anything else except a fluent writer,” she once wrote. Elma Napier flourished in Dominica: it excited her sense of adventure, her curiosity about its people, and her love of wilderness. An early environmentalist, she fought to preserve the island’s great forest ranges, and describes its ecology with an eager eye – from the delights of birdsong and rare orchids to the horrors of cockroach and termite.

Lennox died in 1940, only eight years after their arrival. Elma remained at Pointe Baptiste with its dark glowing furniture, painted screens and books. She continued in her role as hostess – welcoming passing visitors, grand and not so grand, to elegant lunches, although leaving the cooking to the servants. Somerset Maugham, Noel Coward, Patrick Leigh Fermor and Princess Margaret had all sat on that deep veranda with its ever-changing views of mountains and sea.

While life in Dominica became somewhat more prosperous by the 1950s with the arrival of the banana boom, life at Pointe Baptiste remained the same. Elma Napier refused to have a radio – it was the servants who brought her news about the outside world. She said that a “typewriter, pen and sewing machine” were all the moving parts she required. There was no electricity – as the sun began to set beyond the great silhouette of nearby Morne Diablotin, lamps were lit. Once, interviewed by BBC Woman’s Hour about life in Dominica, she had piled on “the discomforts, the oddities” and told her audience about sleeping in police stations where the rats took her food. Being courted by Lennox with a picnic of champagne and gardenias, she wrote that she would have been just as happy with “three ham sandwiches and a bar of chocolate”. There was an appealing no-nonsense, lack of sentimentality to her character, which explains perhaps her ability to flourish in the dynamics of island life at that time.

Dominica has produced two other important women writers, both of the white plantocracy: Jean Rhys and Phyllis Shand Allfrey. Rhys and her husband, the publisher Leslie Tilden-Smith, came to tea at Pointe Baptiste in 1936, but Elma Napier talked books with Tilden-Smith rather than with Rhys, and when Wide Sargasso Sea was published 30 years later, she did not recollect their meeting. She had, perhaps, more in common with Allfrey, also a politician, but although they applauded each other’s work, the two women rarely met, living at opposite ends of the island.

Elma’s first book, of travel sketches, had been published in 1927. There were two novels, published in the 1930s, both set in Dominica: A Flying Fish Whispered (which is to be re-published by Peepal Tree Press), and Duet in Discord. Then came a gap until two memoirs: Youth Is A Blunder (1948), and Winter Is In July (1949) largely about her life in Australia. Black and White Sands was written in 1962, but has remained unpublished until now.

Elma’s death came in 1973, and she is buried, alongside her husband by the track that runs from Pointe Baptiste towards Black Beach. The house itself remains in the family, but is now a holiday rental. Her family continues to contribute to island life: Daphne lives with her family in Dominica, as does Elma’s younger daughter, Patricia, whose son, Lennox Honychurch is a historian and anthropologist. Other grandchildren and great-grandchildren also live and work in Dominica, the island of which Elma wrote: “It has never been easy to analyse, to define the mysterious charm that has lured some people to stay in Dominica forever, and from which others have fled without even taking time to unpack.” Elma Napier stayed forever. Black and White Sands is the fruit of that experience.

Polly Pattullo

1Falling in love

The ship quivered to the wind in the channel. Spray spattered on to the main deck. There was a smell of rubber; a whiff of oil. Far astern the volcano of Martinique hung like a pale triangle between sea and sky. I heard the French consul general say to the lady from South Carolina: “It appears that in Dominica my subordinate is a man of colour. It will not be possible for my wife to go ashore.” And the lady, who wore black kid gloves and a lace veil covering an immense hat, sympathetically concurred.

From the north, dark and clouded mountains were already bearing down upon us with a strange effect of haste, of almost sinister import. Surf reared itself against impassive cliffs to fall back defeated. Vegetation clogged the valleys, shrouded the hills. Not until we were close inshore was there sign of human habitation; a tin roof, a spire, brown houses on stony beaches.

The ship cast anchor off the town of Roseau. Men dived from rafts for “black pennies”, the pale soles of their feet waving in the water like seaweed. There was a clamour of boat owners. “Take Victoria, Mistress.” “Master, White Lily for you.” Buildings with shabby faces lined the bay front. Small fish were making seemingly aimless excursions under a jetty of wooden piles encrusted with sea eggs and barnacles. We sought the Botanical Gardens, and were pestered by small-boy beggars and would-be guides who led us through cobbled streets where wooden houses were mounted on massive foundations. Here and there one might glimpse a courtyard where vines were spread on a pergola behind a sagging mansion. A rampart of cliff overhung three cemeteries wherein the dead of three denominations were blanketed in pink coralita and croton bushes.

Under mahogany trees on a velvet lawn the matron of the hospital routed the little boys. “If you follow that path,” she directed, “you will come to the Morne barracks.” Already, our breath had been taken away by the beauty of the flowering shrubs. “Look at this one,” we cried. “What is that?” Climbing the zigzag path, we stopped at corners to look down on to the red-roofed town and the shining sea, and came at last to a shrine under a talipot palm where the image of Christ was nailed among pointed stakes. At the foot of the cross, tight bunches of oleanders had been thrust into jam jars between lighted candles whose flames were quenched by the afternoon sun. A coloured woman, wearing a silk dress and head kerchief, knelt in prayer. Behind her, an ancient cannon, half buried in the grass, lay as though overthrown by the prince of peace.

Beyond a plot of young lime and orange trees, we found the barracks; stone buildings, three of whose roofs were rusted to the colour of mango flowers while the fourth was altogether missing. They were set square about what had once been a parade ground. There was an old man mowing the lawn and the lazy sound of his machine carried all summer in its droning, so that one could almost smell English grass. He said: “Self-help, Sah? Over there.” And then, feeling perhaps that he had coped inadequately with the sudden appearance of strangers, he removed a tattered straw hat and, wiping his forehead with his arm, said: “Here walk the headless drummer.”

Lennox and Elma Napier in 1932 shortly after arriving in Dominica – “With Dominica we fell in love at first sight, an infatuation without tangible rhyme or reason”.

Suspecting that we had strayed into the local loony bin we approached the best repaired building and there discovered a little old white lady who sold us rum punches in a bare room with tables. There were postcards for sale and bead necklaces; gourds made into rattles with painted faces, and coral fans which – when alive and rooted – sway on the surface of the sea like the fins of sharks. “Government allows us to use this room for the ladies self-help association,” said the diminutive person. I could not refrain from asking: “Help themselves to what?”

The Roseau valley – a typical Dominican landscape of river, mountain and forest.

Therefore it had to be explained that ladies who made jam, or bottled cashew nuts, or did embroidery, might here sell their wares to tourists. But neither my husband Lennox nor I were listening any more: far away up the valley, a waterfall poured out of a black-grey mountain whose summit was hidden in cloud. The veranda rail was wreathed in yellow alamanda, and white flowers shaped like trumpets.

“What a wonderful place to live,” I muttered.

And the little old lady in the guise of Lucifer whispered: “You might rent the other room to sleep in. It would be very primitive. We don’t have many tourists in Dominica.”

“What did the old boy mean about the headless drummer?” Lennox asked.

And she said: “Oh, there’s an old legend from the French wars,” she smiled. “He wouldn’t trouble you.”

Back on the boat that evening, with the moon rising behind the mountains, dinner was eaten to the sound of waltzes and musical comedy selections in a brightly lit salon where the French consul general was seated with a pale and attractive young man who, in a few weeks would be our solicitor. The lady from South Carolina had made acquaintance with a beautiful blonde whose yellow dress and yellow hair had struck me all of a heap across the crowded room.

“But who is she?” I asked the chief engineer, “Who can she be?”

An American, I was told, resident in the island, living among oranges in the high hills in an estate called Sylvania.

“Tell me,” a fellow passenger was saying, “How do you manage here, you a southern girl, meeting coloured people? Do you shake hands?”

And the blonde laughed with a touch of defiance. “Of course,” she said, “I’ve done more than that.”

Thus for the second time in one afternoon, although for the first time in our lives, we met this odd differentiation between persons known as the colour bar, against which we immediately flung ourselves to break it down. (“I tell you they are giants,” said Don Quixote of the windmills. “And I shall fight against them all.”)

Holly Knapp on a garden swing at La Haut. Lennox Napier and Holly Knapp had become friends in Tahiti after the first world war, and met up again by chance in Dominica.

Later, on deck, the same blonde was heard asking someone from the shore, “Who is staying at the Paz Hotel nowadays?”

“There’s an American called Knapp from Fiji, I think,” was the answer whereupon my husband broke excitedly into the conversation. “Knapp?” he said, “with a red beard?” Lennox had known John Holly Knapp 13 years previously in Tahiti, which in this place might easily be confused with Fiji. And instinctively he knew that it must be the same man: the Knapp whose house he had helped to build in Taravao; the Knapp who would not write letters and so lost touch with his friends; the Knapp of whom Frederick O’Brien had written in Mystic Isles of the South Seas: “Without doubt as near to a Greek deity in life, a Dionysus, as one could imagine.... red-gold beard, dark curls over a high forehead, two flaming hibiscus blossoms behind his ears.”

As the Lady Drake was about to sail for Montserrat, Lennox sent a card ashore by the agent, writing on one side of it: “You must be my old friend whom I am sorry to have missed seeing,” and on the other: “My wife and I plan to come back in three weeks’ time.” It was typical of Holly that, on receiving the card, he should have looked at one side only, grieving loudly and bitterly at not having seen Lennox, sticking the evidence into his mirror, until days later, his friend Lorna Lindsley idly removed it and, turning it over, exclaimed: “But they’re coming back.”

That first visit to Dominica was in the winter of 1931. In the autumn of that year we had been living in London with our two children and the grown-up daughter of my first marriage. It was the depression, and Lennox was overtired, overworked, and constantly rather ill. Both of us on the brink of 40, we seemed to be settled and sunk in domesticity, less well-off than we had been, and seeing little prospect of further adventure. Then a lung specialist, stating positively that Lennox showed no evidence of tuberculosis, nevertheless recommended that we take three months’ holiday in search of sunshine, and we chose to go to the West Indies because we knew so little about them.

Between Christmas and New Year we sailed from England for Trinidad in the French ship Colombie, then making her second voyage, and from Port of Spain we took the Canadian national steamship Lady Drake north through the Windward and Leeward islands. Dominica was the only island for which we had no letters of introduction, and with Dominica we fell in love at first sight, an infatuation without tangible rhyme or reason, yet no more irrational than any other falling in love.

When we returned to Dominica – as we had promised ourselves – three weeks later, we climbed into the Paz Hotel by a steep and narrow staircase leading straight off the street into a parlour crowded with basket chairs. Faded and worm-eaten photographs decorated the walls. A tight bunch of croton leaves had been thrust into a brass bowl. Conscious of my hot and crumpled appearance – we had left the pension in Martinique at five that morning and travelled second class in a horrid ship – I went out on to a balcony from which one looked down on to ruined walls. A man and a dog slept side by side on the pavement; a child carried a hand of ripe bananas on her head. Behind the town, mountains were cut into a blue-black frieze against rain clouds.

And there in the Paz was Holly. Attired in a well-fitting white suit with no hibiscus behind the ears, he was not quite my idea of Dionysus. His beard was red indeed but silvered rather than gold. Thus, with mutual pleasure, a friendship made in Tahiti was renewed in the West Indies in 1932.

With Holly that morning in the Paz were Percy Agar, who was to become my son-in-law, and Paul Ninas, an American artist who had lived for three years in the north of Dominica and who, summoned home on account of his father’s mortal illness, had lent his house to Holly. It is funny, remembering my shy flight on to the balcony, to realise that Holly and Lorna thought me too “ladylike” to come camping with them in the rough house built by Paul near Calibishie village; and it was not until Lorna had left the island that the invitation was extended which was to change our lives.

Meanwhile the self-help ladies provided beds, knocked a few nails into a wall, and installed us in two rooms in the old barracks. There were no mosquito nets and we slept badly. “They are only bush mosquitoes,” the ladies said, “they won’t do you any harm.” I looked ruefully at my swollen arms and decided harm had been done. From then on we burned coils of incense which looked like cobras ready to strike and made the room smell like a French church.

The ladies also produced Sarah, an ugly woman, a Seventh Day Adventist, and not a very good cook. On the first evening, she had served dishwater soup and a casseroled chicken cunningly designed to be all bone and no flesh. “It’s a knack peculiar to ‘other races’,” Lennox said. “I remember a Chinese cook in Apia...” And I retaliated with a description of a fowl mangled on a lakeside under Fujiyama. Sarah craved permission to go down the hill to Roseau. “I look for a boy to sleep with me,” she said. In view of her unprepossessing appearance I could only wish her luck with a touch of pessimism. Next morning, a spindle-legged child of 10 emerged from the kitchen. “He my son,” Sarah announced proudly.

May, the messenger, was plump and strong, smiling, and perhaps 17. Returning from town with a basket of vegetables upon her head crowned by a block of ice wrapped in a sack, she would stand by the veranda rail asserting with proud simplicity, “I back.” And indeed it seemed to me that she had reason for pride, for the hill was steep and the load heavy; and I felt slightly ashamed for lying in a deck chair alternately studying Dominican history and throwing bread pellets to lizards. But anyone living so vitally in the present as May would not in the least have cared that battles long ago had been fought in this place, and she would know that lizards – “leezards” – did not require bread.

From one veranda we could see the roadstead streaked with pale currents and dotted with the sails of fishing boats; and from the other the Roseau valley ending in Morne Micotrin whose triangle, at sunrise, would be blackly outlined against a pink sky. At midday, with the peak wreathed in clouds, rainbows would play upon the little village perched on its shoulder. But at sunset, when light filled the dark gullies and the creeper-hung recesses, then the valley would yield its secrets – steam rising from the sulphur springs; patches of the most delicate green sugarcane, lime trees, destined to produce Rose’s lime juice cordial, and always the silver ribbon of the waterfall pouring, so it seemed, out of nothing into nowhere.

Beyond the barracks, a path trailed into a scrubby forest where a stream was clouded with a grey stain as though smoke were held under the surface of the water; and, where it dawdled among huge leaves there was an orange scum, sinister and mephitic. A broken-down hut was rotting in that place, under slimy moss; and a tree fern had pushed off the roof which lay dismembered in the undergrowth. Sadness and decay, a flavour of old, unhappy far off things, underlay the island’s beauty. It has never been easy to analyse, to define the mysterious charm that has lured some people to stay in Dominica forever, and from which others have fled without even taking time to unpack.

We made excursions on horseback hiring quadrupeds from the barber, crossing the backbone of the island by way of a crater called the Freshwater Lake to distinguish it from the Boiling Lake. For days we climbed precipitous ridges or followed red clay tracks within reach of the Atlantic spray; rode through deep forest, silent save for the call of birds; heard for the first time the unhappy note of the siffleur montagne; and forded again and again swift mountain streams, or broader, smoother ones where every day seemed to be washing day, and garments too torn to be identified, too faded for the original colour to be recognised, were spread on stones too hot for the hand to touch.

The bay front, Roseau, Dominica’s capital, as it might have looked in the 1930s. Mural by Elma’s grandson, Lennox Honychurch.

Later, we were rediscovered by the American blonde, Patsy Knowlton, whose preoccupation with new people had brought the name of Knapp into the conversation, and one day, we went to see her and her husband John at Sylvania. We drove on a rough metalled track called the Imperial Road because it had been given to the island in celebration of Queen Victoria’s diamond jubilee. Purple bougainvillea marked the entrance to an old stone house under a saman tree. A broken aqueduct, spotted with ferns and moss, carried water to turn a wooden wheel attached to some invisible machinery. On a narrow col between two watersheds, there was a long low house facing a stupendous panorama of hill and forest which, as clouds passed over, was cut into ever-changing shapes of blue and purple and black.

“Come and look at Morne Diablotin,” said John. “You may never have another opportunity.” And although I have had countless opportunities, I still remember the mountain as it was that day, blue with a touch of sunset gold on it.

“We’ve only been here two years,” they told us, growing oranges commercially. And the first thing that happened was a hurricane. There were photographs taken before the disaster and after when trees lay on the ground and stripped branches cried for vengeance. We understood then why the people of Dominica were so hurricane conscious. Yet already, where destruction had been, we saw hibiscus hedges, gardenias and a white beaumontia vine writhing among the tree tops.

At Sylvania, where we stayed for a few days, small black finches with red breasts would perch on our beds in the mornings, and at the breakfast table would peck the butter, mangle the toast. Sometimes, towards evening, the mountain called Trois Pitons would flame as though it were on fire, and then bats would fly from under the veranda roof in a great cloud and, dispersing into the twilight, be seen no more.

With Holly and Lorna, we walked from the barracks at Morne Bruce to the village of Giraudel. We sat to eat our lunch under a wayside Calvary, such as one might see in Brittany, the figure of Christ on his cross, with a saint on each side. Children brought us, on plates made of banana leaves, fwaises which are not strawberries nor yet quite raspberries, but which grow wild on that side of the island and, like the edible frog called crapaud or mountain chicken, do not cross the dividing range. This area near Giraudel is a dry part of the country, the steep watercourses standing empty, and we were glad when people brought us drinking water in red clay goblets, not realising then how very far they had had to carry it, bringing it up in buckets or kerosene tins from the valley half an hour’s climb away.

At Gomier, the estate of a family named Honychurch, we found three white children swinging on a bamboo stem, one of whom, 20 years later, would marry my younger daughter. Their red-haired mother, who had brought up nine on rather less than the proverbial shoestring, was occupied in writing a piece for the Dominica Chronicle replying for the defence to a priestly condemnation of strange women who walked about the island without stockings.

Percy Agar had sent his overseer to meet us at Gomier that he might show us the cross-country way to his home at La Haut. A huge negro, inappropriately called Cheri, he was naked to the waist, swinging a cutlass, and carrying a bundle suggestive of a severed head dripping blood, which was no more than Lorna’s wet bathing suit done up in a red handkerchief. He led us by a steep path to the La Haut river, almost choked with a white wild ginger, very sweet smelling; and, having crossed over, we came into Percy’s cocoa cultivation – a darkness studded with red and purple and golden pods hanging on thin trunks. It was a long climb up the hill to the lawn under saman trees. It had been a long day.

I lay full length on the veranda and Percy made rum punches for us of whose potency – until I tried to get up – I was unaware (although I felt better for drinking five). A scarlet passion flower enveloped the veranda rail. Little birds called rossignol nested in a box. There was no motorable road to the house. One walked the stony trail between sandbox trees and savonette, coubaril and bay. And when we tried to order a car to meet us at the foot of the hill, we found that the telephone had been cut off that morning because Percy had forgotten to pay the bill.

That was the first time I ever went to the house that was to be the home of my elder daughter, that I ever saw the grass-covered drying ground where coffee beans were once spread to dry on flagstones, the vault which is the hurricane shelter, the ruined chimney smothered in coralita. Beside the lawn at La Haut there is a long low wall with maidenhair fern in its cracks beyond which crotons, frangipani, hibiscus have a background of a blue sea. La Haut has more colour to break the shade of the saman trees than anywhere I know: scarlet of spathodea, yellow of cassia, purple of bougainvillea; begonias and orchids on the trunks of the trees; and, for three days of the year, an outbreak, a superlative blooming, of a yellow vine spread like a mantle over the topmost branches.

That was also the first time we ever saw the emerald drop, that startling flash of green caught for an instant on the horizon as the sun vanishes into the sea and the world turns grey. Minutes after, scarlet banners in the sky proclaimed the day’s death, and tiny lights flickered where the town of Roseau stood on a sand spit at the river’s mouth.

2Dreaming the dream

Paul Ninas’ dwelling place – where Holly was staying – was in the north of the island above the village of Calibishie. It was built in Samoan fashion and consisted of a conical sugar-trash roof set upon 16 posts, with one central pillar to support the rafters. On the circular cement floor stood six chairs, a table, a bed, and an easel on which was the portrait of two nude negroes, one wearing a bowler hat and the other a scarlet handkerchief bound about a halo of tight plaits. Elsewhere were boards and bundles of shingles, for Paul had intended to build a real house when he could afford it. Meanwhile, or presently as the West Indian says, when he means now, this woodpile had become the home of an almost tame agouti, a creature something between a rat and a rabbit, which is indigenous to Dominica, and hunted by men with dogs. Furtively she emerged at intervals to seize the pigeon peas and pieces of sweet potato spread on the floor for her delectation.

We came to this place for the first time at sunset, by a red clay path winding between rows of bay trees. There had been a three-hour journey in the coastal launch from Roseau to Dominica’s second town, Portsmouth, where we waited two hours, and then a rugged hour and a half in the bus. Golden light lay on the sea and on the French islands to the north, Guadeloupe, Marie Galante and the Saints, while the north-east corner of Dominica was lost in purple shadow, with only here and there a distinctive tree standing out against sky or ocean. Outside Paul’s house, called a moulin for its likeness to the local sugar mills, coarse grass and scrubby bushes stretched to the cliff’s edge, below which pink-tipped waves covered flat coral for a width of quarter of a mile before resting on the strip of sand under coconut palms which is Calibishie beach.

Lennox and I took possession of the bed. Holly and his servants slept in his neighbour Clifford Nixon’s house below the bay trees. There were two houseboys, Medly and Copperfield, the latter solemn, wall-eyed, and an assiduous reader of the Bible, marking his place in the Old Testament with a joker and that in the New with the ace of spades. Furthermore, he collected postage stamps in a small tin box which had contained lozenges because he had read somewhere that he would be given a gold watch for a hundred or a thousand or a million.

Medly was a cherubic lad, dark enough, but not toned to quite such boot-black consistency as Copperfield. He was younger, more simple, wearing brilliantly pink shirts and a felt hat. He even served dinner in a hat, and when remonstrated with on this score said he feared the night air, and was seen rubbing off his headgear against one of the posts before coming to the table, reminding one of a horse scratching its back on a fence. Holly, who had lived for so long in the South Seas, tried in the beginning to make his servants wear only a loincloth, the pareu of Tahiti. Friends had assured him that this was impossible, that West Indians would never agree; but when asked to do so Medly and Copperfield had consented immediately. “You see?” said Holly, “one has only to make the suggestion.” Thus were the friends confounded until dinner-time, when the boys appeared wearing the red and white cotton pareus over all their other clothes in the form of a sash, looking like small boys playing pirates.

Every morning at breakfast Medly and Copperfield brought coalpots to the table and toasted bread over the charcoal, piece by piece as Holly directed, crouching as might witches round a cauldron, or priests making a burnt offering on some mysterious altar.

This was Holly’s second winter in Dominica on account of which, and because he was interested in food, he took over the housekeeping. On fine mornings Lennox and I would disappear on to the red rocks or to a beach, and would return to find Holly swinging in a hammock clad only in a loin cloth.

“What is there for lunch?” we would ask, and the invariable reply would be, with a slight note of query as though he were proposing an innovation: “Why, I thought we would have a little salad.” Inevitably, there would be more for lunch than salad but he loved to give the impression that he had sat there for the whole morning pondering how best to blend one tomato, a few string beans, and watercress.

If the weather were unpropitious, then we would watch the process of housekeeping, which went something like this.

“Good morning, Sir, Good morning, Madame. I bring you eggs.”

“How many eggs?”

“I have four eggs, Sir. Two are for money and two are for you.”

For two eggs we used to pay a penny-halfpenny. But the “two-are-for-you” constituted a present for which a return had to be made in kind, either a cigarette or a tot of rum from the demijohn, rum always taken neat with a chaser of water. It was a moot point whether it was more expensive to receive a present or to make a purchase.

“Good morning, Sir. Good morning, Madame. I bring you goat.” Then Copperfield would be sent for.

“Is this young goat, Copperfield?”

And Copperfield would press and pinch the rather unsavoury looking piece of meat and say: “Not very old goat, Sir.” Then the meat would be purchased at sixpence per pound, both sides guessing at the weight, which was generally decided in favour of the vendor.

When Copperfield acquired a piece of meat too good to be stewed on a coalpot then he would borrow, for threepence, the village oven where bread was baked, an oven plastered white, under a thatched roof; and as we came home at dusk our nostrils would be assailed by an infinitely succulent smell.

Or again we would hear: “Good morning, Sir. Good morning, Madame. I bring Madame a present.” This would be a tight bunch of flowers, roses, tiny carnations, Michaelmas daisies, oleanders, with a spray of asparagus fern; and sometimes “roots” – yams or sweet potatoes, or cush-cush, which last is a kind of yam, mashing to a pretty shade of mauve.

Once we had a present of a piece of fish called “cong”. This was identified as conger eel, and was looked at by Medly and Copperfield with the greatest scorn.

“Who sent the cong?” we asked the boy who brought it.

And were told: “Mr Saloo does not use cong, but he send it to you.” Which sounded sinister.

We cooked a piece and gave it to the cat, a cat called Delicat, belonging to Copperfield’s sister, and it neither died nor was sick. So we boiled the rest of the cong with a shilling in the saucepan, for it is said that if fish is bad it will turn silver black. The shilling came out bright and clean, so we ate the cong, and neither died nor were even sick, whereas Medly and Copperfield were impressed and astonished. Only we did not accept any more presents of that particular fish because we did not like it very much.