1,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

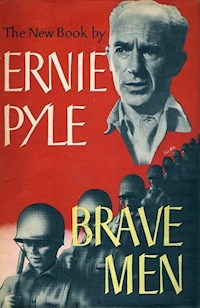

- Herausgeber: Reading Essentials

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Ernie Pyle's gripping account of life on the European front-line during World War II.

Pyle was a Pulitzer Prize-winning American journalist. This is his first-hand account of life on the European front-line during World War II. Written with touching sympathy and humanism,

Brave Men offers a poignant description of the everyday experiences of American foot soldiers; their courage, humanism and unshakeable camaraderie. A must-read war memoir.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

Brave Men

CONTENTS

SICILY

—June-September, 1943

PAGE

1.

INVASION PRELUDE

1

2.

THE ARMADA SAILS

10

3.

D-DAY:—SICILY

18

4.

THE NAVY STANDS BY

32

5.

MEDICS AND CASUALTIES

44

6.

THE ENGINEERS’ WAR

58

7.

CAMPAIGNING

75

8.

SICILY CONQUERED

86

ITALY

—December, 1943—April, 1944

9.

ARTILLERYMEN

92

10.

PERSONALITIES AND ASIDES

117

11.

MOUNTAIN FIGHTING

141

12.

DIVE BOMBERS

156

13.

THE FABULOUS INFANTRY

181

14.

LIGHT BOMBERS

204

15.

LST CRUISE

225

16.

ANZIO-NETTUNO

232

17.

BEACHHEAD FIGHTERS

251

18.

SUPPLY LINE

271

19.

HOSPITAL SHIP

286

20.

FAREWELL TO ITALY

292

ENGLAND

—April-May, 1944

21.

THIS ENGLAND

296

22.

BRASS HATS

306

23.

THE FLYING WEDGE

319

24.

STAND BY

339

FRANCE

—June-September, 1944

25.

THE WHISTLE BLOWS

352

26.

ON THE ROAD TO BERLIN

360

27.

VIVE LA FRANCE

369

28.

AMERICAN ACK-ACK

381

29.

STREET FIGHTING

394

30.

RECONNOITERINGS

408

31.

ORDNANCE

417

32.

BREAK-THROUGH

430

33.

HEDGEROW FIGHTING

440

34.

PARIS

455

35.

A LAST WORD

464

INDEX OF PERSONS AND PLACES

467

IN SOLEMN SALUTE TO THOSE THOUSANDS OF OUR COMRADES—GREAT, BRAVE MEN THAT THEY WERE—FOR WHOM THERE WILL BE NO HOMECOMING, EVER.

I heard of a high British officer who went over the

battlefield just after the action was over. American boys

were still lying dead in their foxholes, their rifles still

grasped in firing position in their dead hands. And the

veteran English soldier remarked time and again, in a

sort of hushed eulogy spoken only to himself, “Brave

men. Brave men!”

—From the author’s here is your war

SICILY

June-September, 1943

1. INVASION PRELUDE

In June, 1943, when our military and naval forces began fitting the war correspondents into the great Sicilian invasion patchwork, most of us were given the choice of the type of assignment we wanted—assault forces, invasion fleet, African Base Headquarters, or whatever. Since I had never had the opportunity in Africa to serve with the Navy, I chose the invasion fleet. My request was approved. From, then on it was simply a question of waiting for the call. Correspondents were dribbled out of sight a few at a time in order not to give a tipoff to the enemy by sudden mass exodus.

Under the most grim warnings against repeating what we knew or even talking about it among ourselves we’d been given a general fill-in on the invasion plans. Some of the correspondents disappeared on their assignments as much as three weeks before the invasion, while others didn’t get the call until the last minute.

I was somewhat surreptitiously whisked away by air about ten days ahead of time. We weren’t, of course, permitted to cable our offices where we were going or even that we were going at all. Our bosses, I hope, had the good sense to assume we were just loafing on the job—not dead or kidnaped by Arabs.

After a long plane hop and a couple of dusty rides in jeeps, I arrived at bomb-shattered Bizerte in Tunisia. When I reported to Naval Headquarters I was immediately assigned to a ship. She was lying at anchor out in the harbor—one of many scores—and they said I could go aboard right away. I had lived with the Army so long I actually felt like a soldier; yet it was wonderful to get with the Navy for a change, to sink into the blessedness of a world that was orderly and civilized by comparison with that animal-like existence in the field.

Our vessel was neither a troop transport nor a warship but she was mighty important. In fact, she was a headquarters ship. She was not huge, just big enough so we could feel self-respecting about our part in the invasion, yet small enough to be intimate. I came to be part of the ship’s family by the time we actually set sail. I was thankful for the delay because it gave me time to get acquainted and get the feel of warfare at sea.

We did actually carry some troops. Every soldier spent the first few hours on board in exactly the same way. He took a wonderful shower bath, drank water with ice in it, sat at a table and ate food with real silverware, arranged his personal gear along the bulkheads, drank coffee, sat in a real chair, read current magazines, saw a movie after supper, and finally got into a bed with a real mattress.

It was too much for most of us and we all kept blubbering our appreciation until finally I’m sure the Navy must have become sick of our juvenile delight over things that used to be common to all men. They even had ice cream and Coca-Cola aboard. That seemed nothing short of miraculous.

We weren’t told what day we were to sail, but it was obvious it wasn’t going to be immediately for there was still too much going and coming, too much hustle and bustle about the port. The activity of invasion preparation was so seething, those last few weeks, that in practically every port in North Africa the harbor lights blazed, contemptuous of danger, throughout the night. There simply wasn’t time to be cautious. The ship loading had to go on, so they let the harbor lights burn.

Our vessel was so crowded it took three sittings in officers’ mess to feed the men. Every bunk had two officers assigned to it; one slept while the other worked. The bunk assigned to me was in one of the big lower bunkrooms. It was terrifically hot down there, so the captain of the ship—a serious, thoughtful veteran naval aviator—had a cot with a mattress on it put up for me on deck and there I slept with the soft fresh breezes of the Mediterranean night wafting over me. Mine was the best spot on the ship, even better than the captain’s.

In slight compensation for this lavish hospitality, I agreed to lend a professional touch to the ship’s daily mimeographed newspaper by editing and arranging the news dispatches our wireless picked up from all over the world during the night. This little chore involved getting up at 3 a.m., working about two hours, then sitting around chinning and drinking coffee with the radio operators until too late to go back to sleep. As a sailor I didn’t have much rest but, as we say in the newspaper business, you meet a lot of interesting radio operators.

In the week aboard ship before we set out on the invasion, I naturally was not permitted to send any columns. I spent the days reading and gabbing with the sailors. Every now and then I would run in to take a shower bath, like a child playing with a new toy.

I got to know a great many of the sailors personally and almost all of them by nodding acquaintance. I found them to be just people, and nice people like the soldiers. They were fundamentally friendly. They all wanted to get home. They were willing to do everything they could to win the war. But I did sense one rather subtle difference between sailors and soldiers, although many of the former will probably resent it: the sailors weren’t hardened and toughened as much as the soldiers. It’s understandable.

The front-line soldier I knew lived for months like an animal, and was a veteran in the cruel, fierce world of death. Everything was abnormal and unstable in his life. He was filthy dirty, ate if and when, slept on hard ground without cover. His clothes were greasy and he lived in a constant haze of dust, pestered by flies and heat, moving constantly, deprived of all the things that once meant stability—things such as walls, chairs, floors, windows, faucets, shelves, Coca-Colas, and the little matter of knowing that he would go to bed at night in the same place he had left in the morning.

The front-line soldier has to harden his inside as well as his outside or he would crack under the strain. These sailors weren’t sissies—either by tradition or by temperament—but they weren’t as rough and tough as the Tunisian soldiers—at least the gang I had been with.

A ship is a home, and the security of home had kept the sailors more like themselves. They didn’t cuss as much or as foully as soldiers. They didn’t bust loose as riotously when they hit town. They weren’t as all-round hard in outlook. They had not drifted as far from normal life as the soldiers—for they had world news every morning in mimeographed sheets, radios, movies nearly every night, ice cream. Their clothes, their beds were clean. They had walked through the same doors, up the same steps every day for months. They had slept every night in the same spot.

Of course, when sailors die, death for them is just as horrible—and sometimes they die in greater masses than soldiers—but until the enemy comes over the horizon a sailor doesn’t have to fight. A front-line soldier has to fight everything all the time. It makes a difference in a man’s character.

I could see a subtle change come over the soldiers aboard that invasion ship. They were no longer the rough-and-tumble warriors I had known on the battlefield. Instead, they were quiet, almost meek; I figured they were awed by their sojourn back in the American way. There was no quarreling aboard between soldiers and sailors, as you might expect—not even any sarcasm or words of the traditional contempt for each other.

One night I was talking with a bunch of sailors on the fantail and they spoke thoughts you could never imagine coming from sailors’ mouths. One of them said, “Believe me, after seeing these soldiers aboard, my hat’s off to the Army, the poor bastards. They really take it and they don’t complain about anything. Why, it’s pitiful to see how grateful they are just to have a hard deck to sleep on.”

And another one said, “Any little thing we do for them they appreciate. We’ve got more than they have and, boy, I’d go three miles out of my way to share something with a soldier.”

A third said, “Yes, they live like dogs and they’re the ones that have to take those beaches, too. A few of us will get killed, but a hell of a lot of them will.”

And a fourth said, “Since hearing some of their stories, I’ve been down on my knees every night thanking God I was smart enough to enlist in the Navy. And they’re so decent about everything. They don’t even seem to resent all the things we have that they don’t.”

The sailors were dead serious. It brought a lump to my throat to hear them. Everyone by now knows how I feel about the infantry. I’m a rabid one-man movement bent on tracking down and stamping out everybody in the world who doesn’t fully appreciate the common front-line soldier.

Our ship had been in African waters many months but the Sicilian invasion was the first violent action for most of its crew. Only three or four men, who’d been torpedoed in the Pacific, had ever before had any close association with the probability of sudden death. So I know the sailors went into that action just as soldiers go into the first battle—outwardly calm but inside frightened and sick with worry. It’s the lull in the last couple of days before starting that hits so hard. In the preparation period fate seems far away, and once in action a man is too busy to be afraid. It’s just those last couple of days when there is time to think too much.

One of the nights before we sailed I sat in the darkness on the forward deck helping half a dozen sailors eat a can of stolen pineapple. Some of the men of the group were hardened and mature. Others were almost children. They all talked seriously and their gravity was touching. The older ones tried to rationalize how the law of averages made it unlikely that our ship out of all the hundreds involved would be hit. They spoke of the inferiority of the Italian fleet and argued pro and con over whether Germany had some hidden Luftwaffe up her sleeve that she might whisk out to destroy us. Younger ones spoke but little. They talked to me of their plans and hopes for going to college or getting married after the war, always winding up with the phrase “If I get through this fracas alive.”

As we sat there on the hard deck—squatting like Indians in a circle around our pineapple can—it all struck me as somehow pathetic. Even the dizziest of us knew that before long many of us stood an excellent chance of being in this world no more. I don’t believe one of us was afraid of the physical part of dying. That isn’t the way it is. The emotion is rather one of almost desperate reluctance to give up the future. I suppose that’s splitting hairs and that it really all comes under the heading of fear. Yet somehow there is a difference.

These gravely-yearned-for futures of men going into battle include so many things—things such as seeing the “old lady” again, of going to college, of staying in the Navy for a career, of holding on your knee just once your own kid whom you’ve never seen, of again becoming champion salesman of your territory, of driving a coal truck around the streets of Kansas City once more and, yes, even of just sitting in the sun once more on the south side of a house in New Mexico. When we huddled around together on the dark decks, it was these little hopes and ambitions that made up the sum total of our worry at leaving, rather than any visualization of physical agony to come.

Our deck and the shelf-like deck above us were dotted with small knots of men talking. I deliberately listened around for a while. Each group were talking in some way about their chances of survival. A dozen times I overheard this same remark: “Well, I don’t worry about it because I look at it this way. If your number’s up then it’s up, and if it isn’t you’ll come through no matter what.”

Every single person who expressed himself that way was a liar and knew it, but, hell, a guy has to say something. I heard oldsters offering to make bets at even money that we wouldn’t get hit at all and two to one we wouldn’t get hit seriously. Those were the offers but I don’t think any bets actually were made. Somehow it seemed sacrilegious to bet on our own lives.

Once I heard somebody in the darkness start cussing and give this answer to some sailor critic who was proclaiming how he’d run things: “Well, I figure that captain up there in the cabin has got a little more in his noggin than you have or he wouldn’t be captain, so I’ll put my money on him.”

And another sailor voice chimed in with “Hell, yes, that captain has slept through more watches than you and I have spent time in the Navy.”

And so it went on one of the last nights of safety. I never heard anybody say anything patriotic, the way the storybooks have people talking. There was philosophizing but it was simple and undramatic. I’m sure no man would have stayed ashore if he’d been given the chance. There was something bigger in him than the awful dread that would have made him want to stay safe on land. With me that something probably was an irresistible egoism in seeing myself part of an historic naval movement. With others I think it was just the application of plain, unspoken, even unrecognized, patriotism.

For the best part of a week our ship had been lying far out in the harbor, tied to a buoy. Several times a day “General Quarters” would sound and the crew would dash to battle stations, but always it was only an enemy photo plane, or perhaps even one of our own planes. Then we moved in to a pier. That very night the raiders came and our ship got her baptism of fire—she lost her virginity, as the sailors put it. I had got out of bed at 3 a.m. as usual to stumble sleepily up to the radio shack to go over the news reports which the wireless had picked up. There were several radio operators on watch and we were sitting around drinking coffee while we worked. Then all of a sudden around four o’clock General Quarters sounded. It was still pitch-dark. The whole ship came to life with a scurry and rattling, sailors dashing to stations before you’d have thought they could get their shoes on.

Shooting had already started around the harbor, so we knew this time it was real. I kept on working, and the radio operators did too, or rather we tried to work. So many people were going in and out of the radio shack that we were in darkness half the time, since the lights automatically went off when the door opened.

Then the biggest guns on our ship let loose. They made such a horrifying noise that every time they went off we thought we’d been hit by a bomb. Dust and debris came drifting down from the overhead to smear up everything. Nearby bombs shook us up, too.

One by one the electric light bulbs were shattered by the blasts. The thick steel bulkheads of the cabin shook and rattled as though they were tin. The entire vessel shivered under each blast. The harbor was lousy with ships and every one was shooting. The raiders were dropping flares from all over the sky and the searchlights on the warships were fanning the heavens. Shrapnel rained down on the decks, making a terrific clatter.

The fight went on for an hour and a half. When it was over and everything was added up we found four planes had been shot down. Our casualties aboard were negligible—three men had been wounded—and the ship had suffered no damage except small holes from near-misses. Best of all, we were credited with shooting down one of the planes.

This particular raid was only one of scores of thousands that have been conducted in this war. Standing alone it wouldn’t even be worth describing. I’m mentioning it to show you what a taste of the genuine thing can do for a bunch of young Americans. As I have remarked, our kids on the ship had never before been in action. The majority of them were strictly wartime sailors, still half civilian in character. They’d never been shot at and had never shot one of their own guns except in practice. Because of this they had been very sober, a little unsure and more than a little worried about the invasion ordeal that lay so near ahead of them. And then, all within an hour and a half, they became veterans. Their zeal went up like one of those skyrocketing graph-lines when business is good. Boys who had been all butterfingers were loading shells like machinery after fifteen minutes, when it became real. Boys who previously had gone through their routine lifelessly had yelled with bitter seriousness, “Dammit, can’t you pass those shells faster?”

The gunnery officer, making his official report to the captain, did it in these gleefully robust words: “Sir, we got the son of a bitch.”

One of my friends aboard ship was Norman Somberg, aerographer third class, of 1448 Northwest 62nd Street, Miami. We had been talking together the day before and he told me how he’d studied journalism for two years at the University of Georgia, and how he wanted to get into it after the war. I noticed he always added, “If I live through it.”

Just at dawn, as the raid ended, he came running up to me full of steam and yelled, “Did you see that plane go down smoking! Boy, if I could get off the train at Miami right now with the folks and my girl there to meet me I couldn’t be any happier than I was when I saw we’d got that guy.”

It was worth a month’s pay to be on that ship after the raid. All day long the sailors went gabble, gabble, gabble, each telling the other how he did it, what he saw, what he thought. After that shooting, a great part of their reluctance to start for the unknown vanished, their guns had become their pals, the enemy became real and the war came alive for them, and they didn’t fear it so much any more. That crew of sailors had just gone through what hundreds of thousands of other soldiers and sailors already had experienced—the conversion from peaceful people into fighters. There’s nothing especially remarkable about it but it was a moving experience to see it happen.

When I first went aboard I was struck with the odd bleakness of the bulkheads. All paint had been chipped off. I thought it was a new and very unbecoming type of interior decoration. Shortly, however, I realized that this strange effect was merely part of the Navy procedure of stripping for action. Inside our ship there were many other precautions. All excess rags and blankets had been taken ashore or stowed away and locked up. The bunk mattresses were set on edge against the bulkheads to act as absorbent cushions against torpedo or shell fragments.

The Navy’s traditional white hats were to be left below for the duration of the action. The entire crew had to be fully dressed in shoes, shirts, and pants—no working in shorts or undershirts because of the danger of burns. No white clothing was allowed to show on deck. Steel helmets, painted battleship gray, were worn during engagements. Men who stood night watches were awakened forty-five minutes early, instead of the usual few minutes, and ordered to be on deck half an hour before going on watch. It takes that long for the eyes to become accustomed to the darkness.

Before we sailed, all souvenir firearms were turned in and the ammunition thrown overboard. There was one locked room full of German and Italian rifles and revolvers which the sailors had got from front-line soldiers. Failure to throw away ammunition was a court-martial offense. The officers didn’t want stray bullets whizzing around in case of fire.

Food supplies were taken from their regular hampers and stored all about the ship so that our entire supply couldn’t be destroyed by one hit. All movie film was taken ashore. No flashlights, not even hooded ones, were allowed on deck. Doors opening on deck had switches just the reverse of refrigerators—when the door was opened the lights inside went out. All linoleum had been removed from the decks, all curtains taken down.

Because of weight limitations on the plane which had brought me to the ship, I had left my Army gas mask behind. Before departure, the Navy issued me a Navy mask, along with all the sailors. I was also presented with one of those bright yellow Mae West life preservers like the ones aviators wear.

Throughout the invasion period the entire crew was on one of two statuses—either General Quarters or Condition Two. “General Quarters” is the Navy term for full alert and means that everybody is on full duty until the crisis ends. It may be twenty minutes or it may be forty-eight hours. Condition Two is half alert, four hours on, four hours off, but the off hours are spent right at the battle station. It merely gives the men a little chance to relax.

A mimeographed set of instructions and warnings was distributed about the ship before sailing. It ended as follows: “This operation will be a completely offensive one. The ship will be at General Quarters or Condition Two throughout the operation. It may extend over a long period of time. Opportunities for rest will not come very often. You can be sure that you will have something to talk about when this is over. This ship must do her stuff.”

The night before we sailed the crew listened as usual to the German propaganda radio program which featured Midge, the American girl turned Nazi, who was trying to scare them, disillusion them and depress them. As usual they laughed with amusement and scorn at her childishly treasonable talk.

In a vague and indirect way, I suppose, the privilege of listening to your enemy trying to undermine you—the very night before you go out to face him—expresses what we are fighting for.

2. THE ARMADA SAILS

The story of our vast water-borne invasion from the time it left Africa until it disgorged upon the shores of Sicily is a story of the American Navy. The process of transporting the immense invasion force and protecting it on the way was one of the most thrilling jobs in this war.

Our headquarters ships lay in the harbor for a week, waiting while all the other ships got loaded. Finally, we knew, without even being told, that the big moment had come, for all that day slower troop-carrying barges had filed past us in an unbroken line heading out to sea. Around four o’clock in the afternoon the harbor was empty and our ship slipped away from the pier. A magnificent sun was far down the arc of the sky but it was still bright and the weather warm. We steamed out past the bomb-shattered city, past scores of ships sunk in the earlier battle for North Africa, past sailors and soldiers on land who weren’t going along and who waved good-bye to us. We waved back with a feeling of superiority which we all felt inside without expressing it; we were part of something historic, practically men of destiny.

Our vessel slid along at half speed, making almost no sound. Everybody except the men on duty was on deck for a last look at African soil. The mouth of the harbor was very narrow. Just as we were approaching the neck a voice came over the ship’s loudspeaker:

“Port side, attention!”

All the sailors snapped upright and I with them, facing shoreward. There on the flat roof of the bomb-shattered Custom House at the harbor mouth stood a rigid guard of honor—British tars and American bluejackets—with our two flags flying over them. The bugler played, the officers stood at salute. When the notes died out, there was not a sound. No one spoke. We slid past, off on our mission into the unknown. They do dramatic things like that in the movies, but this one was genuine—a ceremony wholly true, old in tradition, and so real that I could not help feeling deeply proud.

We sailed on past the stone breakwater with the waves beating against it and out onto the dark-blue of the Mediterranean. The wind was freshening and far away mist began to form on the watery horizon. Suddenly we were aware of a scene that will shake me every time I think of it the rest of my life. It was our invasion fleet, formed there far out at sea, waiting for us.

There is no way of conveying the enormous size of that fleet. On the horizon it resembled a distant city. It covered half the skyline, and the dull-colored camouflaged ships stood indistinctly against the curve of the dark water, like a solid formation of uncountable structures blending together. Even to be part of it was frightening. I hope no American ever has to see its counterpart sailing against us.

We caught up with the fleet and through the remaining hours of daylight it worked slowly forward. Our ship and the other command ships raced around herding their broods into proper formation, signaling by flag and signal light, shooing and instructing and ordering until the ship-strewn sea began to be patterned by small clusters of vessels taking their proper courses.

We stood at the rails and wondered how much the Germans knew of us. Surely this immense force could not be concealed; reconnaissance planes couldn’t possibly miss us. Axis agents on the shore had simply to look through binoculars to see the start of the greatest armada ever assembled up to that moment in the whole history of the world. Allied planes flew in formation far above us. Almost out of sight, great graceful cruisers and wicked destroyers raced on our perimeter to protect us. Just at dusk a whole squadron of vicious little PT boats, their engines roaring in one giant combination like a force of heavy bombers, crossed our bow and headed for Sicily. Our guard was out, our die was cast. Now there was no turning back. We moved on into the enveloping night that might have a morning for us, or might not. But nobody, truly nobody, was afraid now, for we were on our way.

Once headed for Sicily, our whole ship’s crew was kept on Condition Two—all battle stations manned with half crews while the other half rested. Nobody slept much.

The ship was packed to the gunwales. We were carrying extra Army and Navy staffs and our small ship had about 150 people above normal capacity. Sittings went up to four in the officers’ mess and the poor colored boys who waited tables were at it nearly every waking hour. All bunks had at least two occupants and many officers slept on the deck. A man couldn’t move without stepping on somebody.

Lieutenant Commander Fritz Gleim, a big regular Navy man with a dry good humor, remarked one morning at breakfast, “Everybody is certainly polite on this ship. They always say ‘Excuse me’ when they step on you. I’ve got so I sleep right ahead while being walked on, so now they shake me till I wake up so they can say ‘Excuse me.’ ”

Since anything white was forbidden on deck during the operation, several sailors dyed their hats blue. It was a fine idea except that they turned out a sort of sickly purple. It was also the rule that everybody had to wear a steel helmet during General Quarters. Somehow I had it in my head that Navy people never wore life belts but I was very wrong. Everybody wore them constantly in the battle zone. From the moment we left, getting caught without a life belt meant breaking one of the ship’s strictest rules. Almost everybody wore the kind which is about four inches wide and straps around the waist, like a belt. It is rubberized, lies flat, and has two little cartridges of compressed gas—exactly the same things you use in soda-water siphons at home. When pressed, they go off and fill the life belt with air.

I chose for my own life jacket one of the aviation, Mae West type. I took that kind because it holds a man’s head up if he’s unconscious and I knew that at the first sign of danger I’d immediately become unconscious. Furthermore, I figured there would be safety in numbers, so I also took one of the regular life belts. I was so damned buoyant that if I’d ever jumped into the water I would have bounced right back out again.

A mass of two thousand ships can’t move without a few accidents. I have no idea what the total was for the fleet as a whole, but for our section it was very small. About half a dozen assault craft had engine breakdowns and either had to be towed or else straggled along behind and came in late—that was all. Allied planes flew over us in formation several times a day. We couldn’t see them most of the time but I understand we had an air convoy the whole trip.

The ship’s officers were told the whole invasion plan just after we sailed. Also, Charles Corte, Acme photographer, who was the only other correspondent aboard, and I were given a detailed picture of what lay ahead. The first morning out the sailors were called on deck and told where we were going. I stood with them as they got the news, and I couldn’t see any change in their expressions, but later I could sense in them a new enthusiasm, just from knowing.

That news, incidentally, was the occasion for settling up any number of bets. Apparently the boys had been wagering for days among themselves on where we would invade. You’d be surprised at the bad guesses. Many had thought it would be Italy proper, some Greece, some France, and one poor benighted chap even thought we were going to Norway.

One man on the ship had a hobby of betting. He was George Razevich, aerologist’s mate first class, of 1100 Douglas Avenue, Racine, Wisconsin. George was a former bartender and beer salesman. He would bet on anything. And if he couldn’t get takers he’d bet on the other side. Before this trip, George had been making bets on where the ship would go, but he practically always guessed wrong. He was more than $100 in the hole. But what he lost by his bad sense of direction he made up with dice. He was $1,000 ahead on craps. George didn’t make any invasion bets because he said anybody with any sense knew where we were going without being told. His last bet that I heard of was $10 that the ship would be back in the United States within two months. (It wasn’t.)

Every evening after supper the sailors not on duty would gather on the fantail—which seems to be equivalent to the quarter-deck—and talk in jovial groups. We carried two jeeps on the deck to be used by Army commanders when we landed. The vehicles had signs on them forbidding anyone to sit in them, but nobody paid a bit of attention to the signs. Once under way, in fact, there didn’t seem to be the slightest tenseness or worry. Even the grimness was gone.

The fleet of two thousand ships was many, many times the size of the great Spanish Armada. At least half of it was British. The planning was done together, British and Americans, and the figures were lumped together, but in the actual operation we sailed in separate fleets, landed in separate areas. The two thousand figure also included convoys that were at sea en route from England and America. They arrived with reinforcements a few days later. But either section of the invasion, American or British, was a gigantic achievement in itself. And the whole plan was originated, organized and put into effect in the five short months following the Casablanca conference. The bulk of our own invasion fleet came into existence after November of 1942.

The United States Navy had the whole job of embarking, transporting, projecting and landing American invasion troops in Sicily, then helping to fight the shore battle with their warships and afterward keeping the tremendously vital supplies and reinforcements flowing in steadily. After being with them throughout that operation I must say my respect for the Navy is great. The personnel for the great task had to be built as quickly as the fleet itself. We did not rob the Pacific of anything. We created from whole cloth. There were a thousand officers staffing the new-type invasion ships and fewer than twenty of them were regular Navy men. The rest were all erstwhile civilians trained into sea dogs almost overnight. The bulk of the assault craft came across the ocean under their own power. They were flat-bottomed and not ideal for deep-water sailing. Their skippers were all youngsters of scant experience. Some of them arrived with hardly any equipment at all. As one Navy man said, this heterogeneous fleet was navigated across the Atlantic “mainly by spitting into the wind.”

The American invading force was brought from Africa to Sicily in three immense fleets sailing separately. Each of the three was in turn broken down into smaller fleets. It was utterly impossible to sail them all as one fleet. That would have been like trying to herd all the sheep in the world with one dog. The ships sailed from North Africa, out of every port, right down to the smallest ones. It was all worked out like a railroad schedule.

Each of the three big United States fleets had a command ship carrying an admiral in charge of that fleet, and an Army general in command of the troops being transported. Each command ship had been specially fitted out for the purpose, with extra space for “war rooms.” There, surrounded by huge maps, officers toiled at desks and scores of radio operators maintained communications. It was through these command ships that the various land battles were directed in the early stages of the invasion, before communication centers could be set up ashore.

Our three fleets were not identical. One came directly from America, stopping in Africa only long enough for the troops to stretch their legs, then moving right on again. The big transport fleets were much easier to maneuver, but once they arrived their difficulties began. Everything had to be unloaded into the lighter craft which the big ships carried on their decks, then taken ashore. That meant a long process of unloading. When assault troops are being attacked by land, and waiting ships are catching it from the air, believe me the speed of unloading is mighty important.

In addition to the big transports and our hundreds of oceangoing landing craft, our fleet consisted of seagoing tugs, mine sweepers, subchasers, submarines, destroyers, cruisers, mine layers, repair ships and self-propelled barges mounting big guns. We had practically everything that floats. Nobody can ever know until after the war what planning the Sicilian invasion entailed, just what a staggering task it all was. In Washington, huge staffs worked on it until the last minute, then moved bag and baggage over to Africa. Thousands of civilians worked day and night for months. For months, over and over, troops and ships practiced landings. A million things had to be thought of and provided. That it all could be done in five months is a human miracle.

“And yet,” one high naval officer said as we talked about the invasion details on the way over, “the public will be disappointed when they learn where we landed. They expect us to invade Italy, France, Greece, Norway—and all of them at once. People just can’t realize that we must take one step at a time, and this step we are taking now took nearly half a year to prepare.”

Our first day at sea was like a peacetime Mediterranean cruise. The weather was something you read about in travel folders, gently warm and sunny, and the sea as smooth as velvet. But all the same, we kept at a sharp alert, for at any moment we could be attacked by a submarine, surface ship or airplane. And yet, any kind of attack—even the idea that anybody would want to attack anybody else—was so utterly out of keeping with the benignity of the sea that it was hard to take the possibility of danger seriously.

I had thought I might be afraid at sea, sailing in a great fleet that by its very presence was justification for attack, and yet I found it impossible to be afraid. I couldn’t help but think of a paragraph of one of Joseph Conrad’s sea stories which I had read just a few days before. It was in a story called “The Tale,” written about the last war, and it perfectly expressed our feeling about the changeless sea:

“What at first used to amaze the Commanding Officer was the unchanged face of the waters, with its familiar expression, neither more friendly nor more hostile. On fine days the sun strikes sparks upon the blue; here and there a peaceful smudge of smoke hangs in the distance, and it is impossible to believe that the familiar clear horizon traces the limit of one great circular ambush. . . . One envies the soldiers at the end of the day, wiping the sweat and blood from their faces, counting the dead fallen to their hands, looking at the devastated fields, the torn earth that seems to suffer and bleed with them. One does, really. The final brutality of it—the taste of primitive passion—the ferocious frankness of the blow struck with one’s hand—the direct call and the straight response. Well, the sea gave you nothing of that, and seemed to pretend that there was nothing the matter with the world.”

And that’s how it was with us; it had never occurred to me before that this might be the way in enemy waters during wartime.

The daytime was serene, but dusk brought a change. Not a feeling of fear at all but somehow an acute sense of the drama of that moment on the face of a sea that has known so major a share of the world’s great warfare. In the faint light of the dusk forms became indistinguishable. Ships nearby were only heavier spots against the heavy background of the night. Now we thought we saw something and now there was nothing. The gigantic armada on all sides of us was invisible, present only in our knowledge.

Then a rolling little subchaser out of nowhere took on a dim shape alongside us and with its motors held itself steady about thirty yards away. We could not see the speaker but a megaphoned voice came loud across the water telling us of a motor breakdown in one of the troop-carrying barges farther back.

We megaphoned advice back to him. His response returned to us; out in the darkness the voice was youthful. I could picture a youngster of a skipper out there with his blown hair and his life jacket and binoculars, rolling to the sea in the Mediterranean dusk. Some young man who shortly before had perhaps been unaware of any sea at all—the bookkeeper in your bank, maybe—and then there he was, a strange new man in command of a ship, suddenly a person with acute responsibilities, carrying out with great intentness his special, small part of the enormous aggregate that is our war on all the lands and seas of the globe.

In his unnatural presence there in the heaving darkness of the Mediterranean, I realized vividly how everybody in America had changed, how every life had suddenly stopped and as suddenly begun again on a different course. Everything in this world had stopped except war and we were all men of a new profession out in a strange night caring for each other.

That’s the way I felt as I heard this kid, this pleasant kid, shouting across the dark water. The words were odd, nautical ones with a disciplined deliberation that carried the very strength of the sea itself, the strong, mature words of a captain on his own ship, saying, “Aye, aye, sir. If there is any change I will use my own judgment and report to you again at dawn. Good night, sir.”

Then darkness enveloped the whole American armada. Not a pinpoint of light showed from those hundreds of ships as they surged on through the night toward their destiny, carrying across the ageless and indifferent sea tens of thousands of young men, fighting for . . . for . . . well, at least for each other.

3. D-DAY:—SICILY

We had a couple of bad moments as we went to invade Sicily. At the time they both looked disastrous for us, but they turned out to have such happy endings that it seemed as though Fate had deliberately plucked us from doom.

The cause of the first near-tragedy was the weather on the morning of the day on which we were to attack Sicily. The night before, it had turned miserable. Dawn came up gray and misty, and the sea began to kick up. Even our fairly big ships were rolling and plunging and the little flat-bottomed landing craft were tossing around like corks. As the day wore on it grew progressively worse. At noon the sea was rough even to professional sailors. In midafternoon it was breaking clean over our decks. By dusk it was mountainous. The wind howled at forty miles an hour. We could barely stand on deck, and our far-spread convoy was a wallowing, convulsive thing.

In the early afternoon the high command aboard our various ships had begun to wrinkle their brows. They were perplexed, vexed and worried. Damn it, here the Mediterranean had been like a millpond for a solid month, and now this storm had to come up out of nowhere! Conceivably it could turn our whole venture into a disaster that would cost thousands of lives and prolong the war for months. These high seas and winds could cause many serious hazards:

The majority of our soldiers would hit the beach weak and indifferent from seasickness, two-thirds of their fighting power destroyed.

Our slowest barges, barely creeping along against the high waves, might miss the last rendezvous and arrive too late with their precious armored equipment.

High waves would make it next to impossible to launch the assault craft from the big transports. Boats would be smashed, lives lost, and the attack seriously weakened.

There was a time when it seemed that to avoid complete failure the landings would have to be postponed twenty-four hours. In that case, we would have had to turn around and cruise for an extra day, thus increasing the chance of being discovered and heavily attacked by the enemy.

I asked our commanders about it. They said, “God knows.”

Certainly they would have liked to change the plans, but by then it was impossible. We’d have to go through with it. (Later I learned that the Supreme High Command did actually consider postponement.)

Many ships in the fleet carried barrage balloons against an air attack. The quick snap of a ship’s deck when she dropped into a trough would tear the high-flying balloon loose from its cable. The freed silver bag would soar up and up until finally in the thin, high air it would burst and disappear from view. One by one we watched the balloons break loose during the afternoon. Scores of them dotted the sky above our convoy. That night, when the last light of day failed, only three balloons were left in the entire fleet.

The little subchasers and the infantry-carrying assault craft would disappear completely into the wave-troughs as we watched them. The next moment they would be carried so high they seemed to leap clear out of the water. By afternoon, many of the sailors on our vessel were sick. We sent a destroyer through the fleet to find out how all the ships were getting along. It came back with the appalling news that thirty per cent of all the soldiers were deathly seasick. An Army officer had been washed overboard from one craft but had been picked up by another about four ships behind.

During the worst of the blow we hoped and prayed that the weather would moderate by dusk. It didn’t. The officers tried to make jokes about it at suppertime. One said, “Think of hitting the beach tonight, seasick as hell, with your stomach upside down, and straight off you come face to face with an Italian with a big garlic breath!”

At ten o’clock I lay down with my clothes on. There wasn’t anything I could do and the rolling sea was beginning to take nibbles at my stomach, too. Never in my life had I been so depressed. I lay there and let the curse of a too-vivid imagination picture a violent and complete catastrophe for America’s war effort—before another sun rose. As I finally fell asleep the wind was still howling and the ship was pounding and falling through space.

The next thing I knew a booming voice over the ship’s loudspeaker was saying: “Stand by for gunfire. We may have to shoot out some searchlights.”

I jumped up, startled. The engines were stopped. There seemed to be no wind. The entire ship was motionless and quiet as a grave. I grabbed my helmet, ran out onto the deck, and stared over the rail. We were anchored, and we could see the dark shapes of the Sicilian hills not far away. The water lapped with a gentle, caressing sound against the sides of the ship. We had arrived. The storm was gone. I looked down and the surface of the Mediterranean was slick and smooth as a table top. Already assault boats were skimming past us toward the shore. Not a breath of air stirred. The miracle had happened.

The other bad moment came on the heels of the storm. As long as that ship of ours sails the high seas, I’m sure the story of the searchlights will linger on in her wardroom and forecastle like a legend. It is the story of a few minutes in which the fate of the ship hung upon the whim of the enemy. For some reason which we probably shall never know the command to obliterate us was never given.

Our ship was about three and a half miles from shore—which in the world of big guns is practically hanging in the cannon muzzle. Two or three smaller ships were in closer, but the bulk of our fleet stood far out to sea behind us. Our admiral had the reputation of always getting up close where he could have a hand in the shooting and he certainly ran true to form throughout the invasion.

We’d been stopped only a minute when big searchlights blinked on from the shore and began to search the waters. Apparently the watchers on the coast had heard some sounds at sea. The lights swept back and forth across the dark water and after a few exploratory sweeps one of them centered dead upon us and stopped. Then, as we held our breaths, the searchlights one by one brought their beams down upon our ship. They had found their mark.

All five of them, stretching out over a shore line of several miles, pinioned us in their white shafts as we sat there as naked as babies. I would have been glad to bawl like one if it would have helped, for this searchlight business meant the enemy had us on the block. Not only were we discovered, we were caught in a funnel from which there was no escaping.

We couldn’t possibly move fast enough to run out of those beams. We were within simple and easy gunning distance. We were a sitting duck. We were stuck on the end of five merciless poles of light, and we were utterly helpless.

“When that fifth searchlight stopped on us all my children became orphans,” one of the officers said later.

Another one said, “The straw that broke my back was when the anchor went down. The chain made so much noise you could have heard it in Rome.”

A third one said, “The fellow standing next to me was breathing so hard I couldn’t hear the anchor go down. Then I realized there wasn’t anybody standing next to me.”

We got all set to shoot at the lights, but then we waited. We had three alternatives—to start shooting and thus draw return fire; to up anchor and run for it; or to sit quiet like a mouse and wait in terror. We did the last. Our admiral decided there was some possibility they couldn’t see us through the slight haze although he was at a loss to explain why all five lights stopped on the ship if they couldn’t see it.

I don’t know how long the five lights were on us. It seemed like hours, it may have been five minutes. At any rate, at the end of some unbelievably long time one of them suddenly blinked out. Then one by one, erratically, the others went out too. The last one held us a long time as though playing with us. Then it too went out and we were once again in the blessed darkness. Not a shot had been fired.

Assault boats had been speeding past us all the time and a few minutes later they hit the beach. The searchlights flashed on again but from then on they were busy fanning the beach itself. From close range, it didn’t take our attacking troops long to shoot the lights out.

I’m not certain but that some of them weren’t just turned out and left off for good. We never did find out for sure why the Italian big guns didn’t let us have it. Several of us inquired around when we got to land after daylight. We never found the searchlight men themselves, but from other Italian soldiers and citizens of the town we learned that the people ashore were so damned scared by whatever was about to attack them from out there on the water that they were afraid to start anything.

I guess I’m always going to have to love the Italians who were behind those searchlights and guns that night. Thanks to them, St. Peter will have to wait a spell before he hears the searchlight yarn.

Just before daylight I lay down for a few minutes’ nap, knowing the pre-dawn lull wouldn’t last long once the sun came up. Sure enough, just as the first faint light was beginning to show, bedlam broke loose for miles around us. The air was suddenly filled with sound and danger and tension, and the gray-lighted sky became measled with countless dark puffs of ack-ack.

Enemy planes had appeared to dive-bomb our ships. They got a hot reception from our thousands of guns, and a still hotter one from our own planes, which had anticipated them and were waiting.

A scene of terrific action then emerged from the veil of night. Our small assault craft were all up and down the beach, unloading and dashing off again. Ships of many sizes moved toward the shore, and others moved back from it. Still other ships, so many they were uncountable, spread out over the water as far as the eye could see. The biggest ones lay far off, waiting their turn to come in. They made a solid wall on the horizon behind us. Between that wall and the shore line the sea writhed with shipping. Through this hodgepodge, and running out at right angles to the beach like a beeline highway through a forest, was a single solid line of shorebound barges, carrying tanks. They chugged along in Indian file, about fifty yards apart—slowly, yet with such calm relentlessness that I felt it would take a power greater than any I knew to divert them.

The attacking airplanes left, but then Italian guns opened up on the hills back of the beach. At first the shells dropped on the beach, making yellow clouds of dust as they exploded. Then they started for the ships. They never did hit any of us, but they came so close it made our heads swim. They tried one target after another, and one of the targets happened to be our ship.

The moment the shooting began we got quickly under way—not to run off, but to be in motion and consequently harder to hit. One shell struck the water fifty yards behind us and threw up a geyser of spray. It made a terrific flat quacking sound as it burst, exactly like a mortar shell exploding on land. Our ship wasn’t supposed to do much firing, but that was too much for the admiral. He ordered our guns into action. And for the next ten minutes we sounded like Edgewood Arsenal blowing up.

A few preliminary shots gave us our range, and then we started pouring shells into the town and into the gun positions in the hills. The whole vessel shook with every salvo, and scorched wadding came raining down on the deck.

While shooting, we traveled at full speed—parallel to the shore and about a mile out. For the first time I found out how such a thing is done. Two destroyers and ourselves were doing the shelling, while all the other ships in close to land were scurrying around to make themselves hard to hit, turning in tight circles, leaving half-moon wakes behind them. The sea looked actually funny with all those semicircular white wakes splattered over it and everything twisting around in such deliberate confusion.

We sailed at top speed for about three miles, firing several times a minute. For some reason I was as thrilled with our unusual speed as with the noise of the steel we were pouring out. By watching closely I could follow our shells almost as far as the shore, and then see the gray smoke puffs after they hit.

At the end of each run we turned so quickly that the ship heeled far over. Then we would start right back. The two destroyers did the same, and we would meet them about halfway. It was just like three teams of horses plowing a cornfield—back and forth, back and forth—the plows taking alternate rows. The constant shifting put us closest to shore on one run, and farthest away a couple of runs later. At times we were right up on the edge of pale-green water, too shallow to go any closer.

During all this action I stood on a big steel ammunition box marked “Keep Off,” guns on three sides of me and a smokestack at my back. It was as safe as any place else, it kept me out of the way, and it gave me a fine view of everything.

Finally the Italian fire dwindled off. Then the two destroyers went in as close to shore as they could get and resumed their methodical runs back and forth. Only this time they weren’t firing. They were belching terrific clouds of black smoke out of their stacks. The smoke wouldn’t seem to settle, and they had to make four runs before the beach was completely hidden. Then under this covering screen our tank-carrying barges and more infantry boats made for the shore.

Before long we could see the tanks let go at the town. They had to fire only a couple of salvos before the town surrendered. That was the end of the beach fighting in our sector of the American front. Our biggest job was over.

In invasion parlance, the day a force strikes a new country is called D-day, and the time it hits the beach is H-hour. In the Third Infantry Division for which I was a very biased rooter, H-hour had been set for 2:45 a.m., July 10.

That was when the first mass assault on the beach was to begin. Actually the paratroopers and Rangers were there several hours before. The other two large American forces, which traveled from North Africa in separate units, hit the beaches far down to our right about the same time we did. We could tell when they landed by the shooting during the first hour or so of the assault.

Out on our ship it seemed to me that all hell was breaking loose ashore, but later when I looked back on it, actually knowing what had happened, it didn’t seem so very dramatic. Most of our special section of coast was fairly easy to take, and our naval guns didn’t send any fireworks ashore until after daylight. The assault troops did all the preliminary work with rifles, grenades and machine guns. From our ship we could hear the bop, bop, bop of the machine guns, first short bursts, then long ones.

I don’t know whether I heard any Italian ones or not. In Tunisia we could always tell the German machine guns because they fired so much faster than ours, but that night all the shooting seemed to be of one tempo, one quality. Now and then we could see a red tracer bullet arcing through the darkness. I remember one that must have ricocheted from a rock, for suddenly it turned and went straight up a long way into the sky. Once in a while there was the quick flash of a hand grenade. There wasn’t even any aerial combat during the night and only a few flares shot up from the beach.

In actuality, our portion of the assault was far less spectacular than the practice landings I’d seen our troops make back in Algeria.

A more dramatic show was in the sector to our right, some twelve or fifteen miles down the beach. There the First Infantry Division was having stiff opposition and its naval escort stood off miles from shore and threw steel at the enemy artillery in the hills. On beyond, the Forty-fifth had rough seas and bad beaches.