35,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

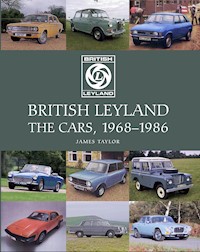

In 1968, British Leyland brought together many of Britain's motor manufacturers, with the intention of creating a robust unified group that could equal the strength of the big European conglomerates. But this was not to be. There have been many books about the politics and the business activities of British Leyland, but British Leyland - The Cars, 1968-1986 looks exclusively at the cars that came from the company, both the models it inherited and those it created. The eighteen years of the corporation's existence saw a confusing multitude of different car types, but this book resolves these confusions, clarifying who built what, and when. The book takes 1986 as its cut-off point because this was the year that the old British Leyland ceased to exist and what was left of the car and light commercial business was renamed the Rover Group. The book includes: Production histories and technical specifications of every major model; The special overseas models; Appendices on engines, code names, and factories; Buying guidance on the models built in Britain. This is the most comprehensive book so far to focus on the cars from British Leyland between 1968-1986 and it provides an overview of each model's production history, together with essential specification details. It is profusely illustrated with 178 colour and 63 b&w photographs.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

BRITISH LEYLAND

THE CARS, 1968–1986

JAMES TAYLOR

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2018 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2018

© James Taylor 2018

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of thistext may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 392 9

CONTENTS

Introduction and Acknowledgements

CHAPTER 1 AN OVERVIEW OF BRITISH LEYLAND

CHAPTER 2 THE INHERITANCE

CHAPTER 3 THE BRITISH LEYLAND MODELS

CHAPTER 4 OVERSEAS ODDITIES

Appendix I: The Engines

Appendix II: Code Names

Appendix III: British Leyland Car Assembly Plants in the UK

Index

INTRODUCTION AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The story of British Leyland is a vast one, and already there have been many books and monographs that have tackled aspects of it. There are many different ways of looking at the story, but this book deliberately focuses on the cars and car-derived commercial products. The story of the company’s evolution in the first section is designed to provide essential background to those products, and is not in any sense intended as an in-depth study of what is an enormously complicated piece of British social, economic and political history.

Surprisingly perhaps, defining exactly what was a British Leyland product and what was not is by no means straightforward. The approach taken here is a logical one, which separates the products into two groups: those that were inherited at the formation of BLMC in 1968, and those that were developed or reached the showrooms during the British Leyland era.

Inevitably these groups are complicated by the fact that some inherited products were further developed under British Leyland; the Mini, as an extreme example, was inherited, but survived right through the British Leyland era and beyond. The solution I have chosen is to discuss the further development of ‘inherited’ models in the chapter devoted to them, but to treat any major change as the creation of a new model, therefore including it in the British Leyland chapter. So, to follow the example of the Mini, the story of the ‘inherited’ Mk II models is in the earlier chapter, but from the point where they became Mk III models with Leyland badges, they are in the later chapter.

As for a cut-off point, I have chosen 1986 because this was the year that the old British Leyland ceased to exist, and what was left of the car and light commercial business was renamed the Rover Group. Inevitably, some new models appeared right on the cusp of the changeover – a notable example being the Rover 800. However, even though these were developed under British Leyland, they were not sold during that company’s lifetime and are therefore not included in this book.

Vitally important in the British Leyland story is the question of exports. Listing all the countries to which each individual model was exported would be tedious and probably not very enlightening. So would the full story of all the overseas assembly plants that built BL models from CKD. However, where overseas plants developed distinctively different models, I have guessed that their story might be of more interest, and so have included these in a further chapter.

Next, British Leyland used an enormous and potentially confusing variety of engines in its car and car-derived commercial ranges in this period. To avoid complicating the main text, and to avoid a degree of repetition, I have put the details of all these engines in an Appendix. Finally, British Leyland inherited a large number of factories, and another Appendix provides a ready reference to these.

Throughout this book, every effort has been made to ensure technical accuracy. I have drawn on a large number of sources for the information in it, and I have also tapped into the knowledge and the memories of a very large number of people. To all those who contributed their thoughts and ideas, here is my chance to say thank you, and to apologise if I have misunderstood what you tried to tell me.

James Taylor

Oxfordshire, 2017

1 AN OVERVIEW OF BRITISH LEYLAND

THE STORY OF BRITISH LEYLAND is an enormously complicated one, and the purpose of this section is simply to provide a framework to act as background to the story of the cars it produced. Indeed, it is sometimes difficult to determine exactly when British Leyland began and when it ended; the dates chosen for this book are 1968, when the British Leyland Motor Corporation was formed, and 1986, when what was left of that grouping was formally renamed as the Rover Group.

One other point needs to be made at the start. British Leyland was a vast organization, with manufacturing interests in many areas beyond cars and light commercial vehicles. This book makes no attempt to deal with these other interests: it is purely about those cars and the light commercials that were directly derived from them.

The British Leyland Motor Corporation, 1968

BLMC formally came into being on 17 January 1968, and was the result of a merger between British Motor Holdings (BMH) and the Leyland Motor Corporation. BMH was then the largest car manufacturer in Britain, nearly twice the size of the Leyland group. It had been formed as BMC (British Motor Corporation) in 1952 by the merger of Austin and the Nuffield Organisation. In 1966 it had become BMH, when Jaguar and its Daimler subsidiary joined the fold. Leyland, meanwhile, was a long-established truck and bus manufacturer that had branched out into car manufacture by taking over Standard-Triumph in 1961.

The 1968 merger was brokered by the Industrial Reorganization Committee, which was then run by Tony Benn. It was an organization established by the Labour Government under Harold Wilson to create a more efficient British industrial base through mergers and reorganization. While the Leyland group was in a strong position, BMH was getting dangerously close to collapse, partly because many of its models were outdated.

Benn was particularly concerned that Britain had no motor industry group big enough and strong enough to counter the major groups in Europe, particularly Volkswagen. He believed that merging the two British groups would produce a group large enough to achieve this, and would also save BMH from collapse. Over the summer of 1967, he encouraged talks between the top management of both sides, and agreement was reached.

There was no doubt that the Leyland group was the stronger partner in the new alliance, and it was a Leyland man who was appointed as Chairman and Managing Director of the new British Leyland Motor Corporation. He was Sir Donald Stokes, who had made his name particularly through export sales, and he was a clear-thinking and often ruthless individual.

British Leyland used this instantly recognizable ‘flying wheel’ logo. The flying wheel was later used on its own without the words.

First Stages

One of the first tasks that fell to Sir Donald Stokes after the merger was to examine the future products portfolio of the companies he now controlled. He was reportedly quite shocked to find that what had once been BMC (principally Austin and Morris) had very little on the stocks. The Austin Maxi was on the way, and work was being done on a planned replacement for the Mini, called 9X. But there were no plans to replace the big-selling medium-sized models, the Morris Minor, the 1100/1300 range, or the larger 1800 saloons.

Architects of British Leyland’s early days: Stokes is on the left, his Financial Director John Barber is in the middle, and on the right is George Turnbull, who was then Managing Director of the Austin-Morris division. ALAMY

Stokes clearly thought that much of the blame for this deficit in the future product programme could be laid at the door of Alec Issigonis, the Technical Director of BMC. So he rapidly sidelined him in a management shake-up, giving him the new job of Special Developments Director. He moved Harry Webster from Triumph to replace him, now with the job title of Technical Director, Small and Medium Cars; and as Triumph’s new Technical Director he appointed Spen King, who had been in charge of Rover’s future model think-tank.

All this happened in and around May 1968, and on 12 June, Stokes addressed a meeting of former BMC distributors at Longbridge, promising them a completely new model policy over the next five years under the direction of Harry Webster. Webster was a very shrewd choice, as he had overseen the engineering of a company that had produced not only sports cars but also ‘executive’ saloons, and had experimented with front-wheel drive for its medium saloons as well.

Stokes also decided to recruit new management talent from outside BLMC in order to inject some fresh thinking into the company. One of his first appointments was John Barber, an experienced former Ford man who became BLMC’s Finance Director and Stokes’ right-hand man. Ford was then regarded as the best training ground in Britain for motor industry managers, and over the next few years a sizeable number of former Ford employees were recruited to BLMC. They certainly did inject some new ideas, but they also aroused a degree of suspicion among the established workforce: they were not members of the ‘tribe’ associated with each of the old companies, and they wanted to do things differently.

The rest of the Stokes management team was almost exclusively drawn from the Leyland side, but it would be wrong to suggest that this was favouritism. The fact was that BMH was in a bad way, which strongly suggested that new management was needed to sort it out. So its former top management was scattered: Joe Edwards, the Managing Director, was retained as a consultant, though he quickly saw which way the wind was blowing and resigned in July 1968. The new Austin-Morris division, which was really a continuation of what had once been BMC, went to George Turnbull, a Leyland man whose career had begun with Standard. And as his two deputy chairmen on the new BLMC Board, Stokes appointed Sir William Lyons of Jaguar and Lewis Whyte, who had been on the Leyland Board since 1964.

Resolving Model Clashes

Quite rightly, Stokes and his team concentrated their initial energies on the failing enterprise that had once been BMC; this was where the major problems lay, and the model clashes with the former Leyland companies could be resolved later.

It was immediately obvious that there was far too much duplication of products among the marques once owned by BMC. So as a start, the Stokes team decided that Austin and Morris would in future be more clearly distinguished: Morris badges would go on cars with conventional engineering, and Austin badges would be reserved for cars with the advanced front-wheel-drive layout and other innovations that had been Alec Issigonis’ speciality. Some of the other former BMC marques, which only existed as ‘badge-engineered’ versions of Austin and Morris models, would have to go. The first that did so was Riley, which disappeared in 1969.

Most importantly, the Stokes team wanted new products. Stokes wanted BLMC to make a big splash in summer 1970 (just over two years away) with some stunning new models. So he applied pressure on Triumph to deliver their new Stag grand tourer, and on Rover to deliver their new Range Rover. Both did appear in summer 1970, although in each case the final stages of development were rushed in order to meet that tight deadline.

Meanwhile, Harry Webster’s first task on taking over the Small and Medium Cars Division was to put together a crash programme for developing new models. Meeting that summer 1970 deadline was virtually impossible, but Webster tried. He drew up a conventional car that would appeal to fleet buyers and could be engineered using largely existing production components. This became the Morris Marina – but despite heroic efforts it was actually delivered later than Stokes wanted, in 1971.

A particular problem resulting from the merger of two companies that had formerly been rivals was that there were several overlaps and clashes between their product ranges (see sidebar for a list of the most obvious model clashes). So the next job for the Stokes team was to resolve those clashes and streamline the product range so that the BLMC marques would not be in competition with one another. Over the years, this would prove to be an enormous undertaking, not least because of the tribal loyalties and vested interests of those who had spent many years working for one of the companies whose identity was to be lost. It was one cause of the industrial unrest that plagued British Leyland in the 1970s – although it was far from the only one.

The Stokes team faced their first challenges in 1969 when a new sports car designed by Rover (in a departure from their usual model portfolio) threatened to clash with the Jaguar E-type. They refused funding for the Rover. A further clash with Jaguar resulted in the big Rover P8 saloon being cancelled in 1971.

Shortly after that another clash arose between Rover and Triumph. Both companies had started work on replacements for their existing saloon models of similar size, and it was clearly absurd for both to proceed. Stokes resolved that the two engineering teams should work together on a single new model from early 1971, and that car eventually wore Rover badges. In early 1972, the two marques were then formally merged as the Specialist Division of BLMC. At about the same time, the old Austin-Morris teams under Harry Webster were renamed as the Volume Cars Division.

In the early days, when company identities were still being retained, the BL logo was often seen in tandem with the individual marque names. This one dates from 1970.

There were some anomalies in these two broad groupings. Jaguar and Daimler were theoretically part of the Specialist Division, but they always did their best to remain aloof from it. Triumph’s medium-sized saloons and sports cars belonged to the Specialist Division, while MG’s sports cars belonged to the Volume Cars Division. While Land Rover sat fairly comfortably in the Specialist Division with Rover, the Austin and Morris light commercials belonged to the Volume Cars side. But this reorganization was at least a step in the direction of rationalization.

However, in resolving product issues, the Stokes team neglected to deal with problems of over-manning and poor productivity. Strong unions made it difficult to tackle both, and there was no doubt that any major efforts to tackle these issues would lead to strikes. By the early 1970s, compromises that the Heath government made with unions in other industries suggested that there was a lack of political will to confront them, and this would certainly not have encouraged the Stokes team to take any bold steps that would lead to union trouble.

The two cars perhaps most closely identified with the British Leyland were the Morris Marina and the Austin Allegro. Both were introduced in the early 1970s, and their relative failure – for reasons explained in Chapter 3 – has become an enduring symbol of the British Leyland period. The Marina was an unexceptional and deliberately conventional model… © MCP

Productivity was indeed poor. An article in Motor for 29 May 1976 compared the number of cars produced per employee by various car makers during 1975, and the comparisons were quite shocking. In Japan, Toyota produced thirty-six cars per employee, and Honda produced nearly twenty-three. In Britain, British Leyland produced just over four cars per employee. Although various factors made these comparisons inexact, it was abundantly clear that the British car industry as a whole was lagging behind, and not just British Leyland. Even Ford’s UK factories managed a miserable figure of just over seven cars per employee. This was a fierce condemnation of the failure of British car makers to invest in modern production processes, as well as to deal with the steadily rising power of their trades unions.

… while the Allegro was intended to incorporate modern technology and advanced styling.

MODEL CLASHES

When BLMC was formed in 1968, an inevitable result was that there were multiple model clashes. Formerly rival companies operating in the same market sectors each had their own products, and it was obvious that a coherent new manufacturing policy could only be created by scrapping some products in favour of others.

In their attempts to do that, Stokes and Barber encountered rebellion and resentment from those whose products faced being sidelined. In some cases they chose to wait until British Leyland could replace two formerly rival products by a single new one. What follows is a rapid overview of the problems that they faced in 1968; only in the small car sector, where the Mini had no direct competition, were their decisions easy.

Medium saloons with front-wheel drive: Austin had pioneered front-wheel drive in the medium family saloon sector with its ADO16 (1100 and 1300) range, but Triumph had mounted a challenge with its own medium-sized front-wheel-drive saloon (the 1300) from 1965. Both remained in production.

Medium saloons with rear-wheel drive: All the internal competition in this sector of the market was from badge-engineered versions of the same BMC 1.6-litre design, which was available as an Austin, an MG, a Morris and a Wolseley. These were elderly models, which could be allowed to wither away.

Large saloons: Austin had the front-wheel-drive 1800, which had no direct rivals because of its sheer size, although it was priced like a medium-sized family saloon.

Executive saloons: Rover and Triumph had been rivals in the executive saloon market ever since 1963, when the Rover 2000 and Triumph 2000 had both been introduced. Both model ranges had been expanded upwards since then, but both were still competing for essentially the same group of customers.

Sports saloons: Riley and Triumph both had entries in this sector of the market, but there was no competition for the Jaguar models at the more expensive end of the sector.

Luxury saloons: There were some very obvious overlaps in the luxury saloon sector. Austin, Daimler, Jaguar, Rover and Vanden Plas were all making cars in the 3-litre-and-over class, and it was nonsensical to continue with all of them.

Sports cars: There were no fewer than four sports-car marques in the new British Leyland combine, and two of these – MG and Triumph – had been deadly rivals since the early 1950s. The third, Austin-Healey, was no less well regarded, although by 1968 it had no unique models and its only product was a badge-engineered MG (although, ironically, the design was by Austin-Healey). The fourth sports-car maker was Jaguar, which produced models that were generally much more expensive than the other three marques.

Crisis and Nationalization, 1974–75

Unfortunately, Stokes’ new models were not arriving fast enough to keep sales afloat, and industrial troubles had their effect on productivity. A boom in car sales during 1972 should have given BLMC a boost, but it had exactly the opposite effect because the company was unable to meet the increased demand. The gap was filled by Ford, who were able to boost production, and by increasing the numbers of foreign imports. The BLMC market share of UK car sales had hovered around 40 per cent for several years, but in 1972 it slid to 33.1 per cent, and then continued to fall.

BLMC’s position was not healthy even by mid-1973, but the knock-out blow came as a result of the long coal miners’ strike that began in November 1973 and lasted for five months. The strike cost the company an enormous amount of money – some three-quarters of a billion pounds sterling – as it generated emergency power to maintain production and air-freighted after-sales replacement parts to the UK from around the world in order to maintain limited production of new cars.

Meanwhile sales had slumped, too, in the wake of the oil crisis that had erupted that autumn. In early October, Egypt and Syria had launched a co-ordinated attack against Israel in the hope of regaining territory lost during the 1967 Arab-Israeli war. Israel had successfully fought them off, seizing even more territory than before, and a cease-fire had been declared before the end of the month. However, the Arab association of oil producers (OPEC) now tried a form of blackmail to force territorial concessions by Israel that would allow the Palestinians their own state. They put pressure on Israel’s Western allies by cutting oil supplies to some and raising oil prices for others. In Britain, fuel prices escalated and car sales slowed dramatically – all at a time of serious inflation, which would reach 23 per cent by June 1975.

The BLMC Board desperately examined a multitude of options to keep the company afloat. In February 1974 it decided to close as many as possible of the company’s manufacturing plants outside the UK, and to realize the assets in order to provide cash that might offset the continuing losses. Stokes is alleged to have approached the Shah of Iran during 1974 to ask for investment, and it is also said that he tried to give away the Volume Cars Division in order to stem the company’s losses – but that nobody was interested.

By late 1974, the position had become critical. BLMC was facing bankruptcy, and had to go cap-in-hand to Harold Wilson’s new Labour government to seek financial support. This was granted – the alternative facing the government was to see thousands of motor industry employees suddenly out of work – but on a number of conditions. One was that the government itself would become a majority shareholder in BLMC, and would have a say in its corporate future. So a new holding company was created with the name of British Leyland Ltd (almost universally known as BL) so that this could happen. Both the company’s budget and, bizarrely, its decisions about future products, became subject to government scrutiny and approval.

Sadly, the collapse of British Leyland seemed to be perfectly in tune with the socio-political atmosphere of the times. The early 1970s were a period when Britain had largely lost faith in itself, and so the 1974 collapse was just another highly public British disaster in a chain of many. In such an atmosphere it was hardly surprising that domestic car buyers came to the conclusion that BL’s cars were somehow sub-standard. The public feeling was that if it had been made in Britain, it could not be any good, and of course foreign manufacturers were not slow to recognize their opportunity. Within a couple of years, BL had lost so much ground that a simply massive effort would be needed to make it viable again.

That massive effort would require constant injections of government capital throughout the remaining lifetime of British Leyland and beyond.

Ryder and After, 1975–76

In effect, BLMC had been nationalized, and unsurprisingly the government immediately commissioned a report into its affairs, appointing its industrial adviser Sir Don Ryder to do the job. Ryder was the Chairman of the National Enterprise Board, which oversaw government financing of nationalized industries and large state-owned enterprises in the UK. His report was prepared in double-quick time, and was published in April 1975. It was fairly damning of BLMC’s failings, and it made a number of recommendations. One of these was that the separate marques and car divisions should be merged into a single company to be called Leyland Cars. There were also several recommendations regarding future government funding to enable BLMC to get back on its feet and become competitive again.

Changes in the top management inevitably followed the Ryder Report. The report created the new role of Non-Executive Chairman, a part-time post that was given to Professor Sir Ronald Edwards, former Chairman of the Beecham Group. Ryder himself kept a close eye on developments from his position at the National Enterprise Board. Stokes was appointed President to remove him from the day-to-day running of the organization, and would remain on the British Leyland Board until 1979. Alex Park became Finance Director, replacing John Barber, who resigned.

In the mid-1970s, the British Leyland identity was suppressed in favour of the Leyland Cars identity.

Supercover was the brand name given to the warranty system, and the logo seen here comes from a 1977 sales brochure.

The company name also made its way on to the VIN plates displayed on the cars.

The new branding appears on a Leyland Cars all-model brochure issued in autumn 1975 for the 1976 season.

There would be two further changes at the top: Professor Sir Ronald Edwards died in January 1976, and his post was taken by Sir Richard Dobson, who had been Chairman of British American Tobacco. He remained in place until October 1977, when he was obliged to resign after making some unacceptable remarks during a speech. In fact, the NEB had already decided that British Leyland needed a full-time chairman, and had offered the job to Michael Edwardes, the CEO of the Chloride Group and a member of the NEB. Edwardes accepted and took over in late October.

The Edwardes Era, 1977–82

Edwardes was prepared to be ruthless to slim British Leyland down to a viable size, and one of his first moves was to reduce the size of the Board from thirteen members to just seven. He also swiftly recognized that some of the enthusiasm for the Ryder reforms was already waning, and in particular the idea of burying the individual car marques in the common identity of Leyland Cars.

This imaginative ‘motorway flyover’ cover was used for the all-models catalogue of the 1978 season.

So during 1978 he scrapped Leyland Cars, breaking it up into smaller, semi-autonomous business units. The two big ones were Austin-Morris and Jaguar-Rover-Triumph, which more or less (but not quite) corresponded to the earlier Volume Cars and Specialist Cars divisions. Key differences were that MG now belonged to what was usually known as JRT, while Land Rover was managed quite separately, and would come to belong to a new business unit called the Land Rover Group, which also had responsibility for light commercial vehicles.

Edwardes made sure that all these business units had their own management to run their-day-to-day affairs. At Austin-Morris, he appointed Ray Horrocks as Managing Director. At JRT, the Chairman was William Pratt Thompson, and Jeff Herbert was appointed Managing Director. Jaguar was a very reluctant member of this division, and always did its best to remain aloof from the Rover-Triumph and MG side; later, JRT would be split into Rover-Triumph and Jaguar Car Holdings (which included Daimler). David Abell was put in charge of a newly created division called BL Commercial Vehicles. David Andrews became Chairman of the Land Rover Group, and Mike Hodgkinson became Managing Director of Land Rover, with Tony Gilroy as Managing Director of the light commercial business, which in 1981 took on the name of Freight Rover.

Brought in to get a grip on British Leyland, Sir Michael Edwardes did exactly that.

However, it was not all plain sailing for Edwardes. Trade unionist leader Derek Robinson – known as ‘Red Robbo’ – (left) was a constant thorn in his side.

Not often thought of as a British Leyland car, the Mini was introduced before the company was formed and outlasted it by several years as well. This pristine 1275 GT is fitted with a rare British Leyland tuning kit.

For a time, the light commercial vehicles were grouped together under the Freight Rover division, which had its own logo. In practice, the Freight Rover name only ever appeared on the Sherpa van, which was not a car-derived vehicle.

The chevron logo was a neat idea to link all the British Leyland brands. It later appeared in several slightly different forms, often without the brand names, and was still in use when the Maestro and Montego came on the scene in the first half of the 1980s.

For the 1979 season, the marques were being re-emphasized, and this catalogue covered Jaguar Rover Triumph.

Several British Leyland cars were assembled overseas, including the Mini. This brochure was for the Innocenti Mini Cooper 1300, which was assembled in Italy.

The flying-wheel logo has now lost its central L; this is an all-models catalogue from the 1981 season.

Reorganization yet again: this autumn 1982 catalogue was for the recently created Austin Rover Group.

Edwardes pressed on with his comprehensive restructuring plan, and implemented its final stages in 1981. Austin Rover Group became the new name for the mass-market car-manufacturing subsidiary, combining what was left of Austin-Morris and Jaguar-Rover-Triumph. The Land Rover Group and Jaguar Car Holdings remained separate. In the meantime, Edwardes drastically reduced the number of UK car dealerships, and closed a number of factories.

He had closed the Triumph factory at Speke in 1977 after an all-out strike had disrupted TR7 sports-car production, and in 1980 he closed the MG plant at Abingdon. The main Triumph plant at Canley followed, although the site survived as an administrative, engineering and design headquarters. Before long, the eight Leyland car assembly plants had been reduced to just three – Cowley (traditional home of Morris), Longbridge (traditional home of Austin) and Solihull (traditional home of Rover). And there would be more shuffling of production in 1982 as Rover cars moved out of Solihull to allow that plant to become the dedicated centre of Land Rover production.

The Honda Alliance

By the time Edwardes became British Leyland’s Chairman, several reports into the company’s affairs had agreed that its long-term survival could only be guaranteed by a strategic alliance with another car manufacturer. So the Edwardes team explored a number of options as a high priority. It was essential to find a partner of similar size to BL if the British company was not to end up as the junior partner.

At the same time, BL urgently needed a replacement for the Austin Allegro, which was already dying in the market place and was not scheduled to be replaced until 1983. Its replacement, the LC10 or Austin Maestro, could not be launched any earlier because BL simply did not have the necessary engineering resources. So it became clear that BL’s new partner had to be a company with a suitable car in the pipeline, and one that was prepared to share that car with BL.

Ray Horrocks at the Austin-Morris division worked with product planner Mark Snowden to draw up a list of companies that fitted the profile. Chrysler UK was at the top of that list, and Honda was number two. BL initiated talks with a wide range of European manufacturers, such as BMW, Fiat and Renault, but seem to have been pinning their hopes on discussions with Chrysler UK over the summer of 1978. Unfortunately, the Chrysler operation was in a worse state than BL’s, and when Peugeot offered to take it over that year, the French company was welcomed with open arms.

So the focus switched to Honda. Talks began in August 1978 and went well; the two companies signed a Memorandum of Understanding on 15 May 1979, and in October that year the BL Board approved a draft agreement, which was later ratified under BL’s 1980 Corporate Plan. In due course, a cross-holding arrangement was put in place: Honda took a 20 per cent shareholding in British Leyland, which in return took a 20 per cent shareholding in Honda UK. There would be close co-operation in the development of new models, enabling Honda to get a foothold in the European market and BL to develop new models more quickly and for less cost.

The first fruit of the agreement was that British Leyland announced the Triumph Acclaim in late 1981. Cosmetically, it replaced all the Triumph Dolomite range, but the truth was that it was a holding operation to regain buyer confidence until the planned LC10 was ready. It was simply a Honda model, built in Britain and rebadged, but it gave British Leyland the most reliable car it had built for many years. Ordinary though it was, it did exactly what was asked of it. Meanwhile, Jaguar Rover Australia (BL’s Australian subsidiary) also agreed with Honda to take one of its existing models to fill a gap in its own model range.

The Acclaim was replaced during 1984 by another Honda design, this time re-engineered and restyled to some extent in Britain. In accordance with the latest branding arrangements, this became a Rover 200 series. And in the meantime, work went ahead with all speed on a proper joint project to develop a new big saloon, which would be sold as a Honda Legend and as a Rover 800 series. The introduction of that car in 1986 more or less coincided with the end of British Leyland as it took on the new name of Rover Group.

RING IN THE NEW

Listed below are major new model introductions under British Leyland, 1968–86: these are UK-built types; overseas confections are not listed. Typically, new models were announced in the calendar year before their first model year, so that a model announced in 1970 would be for the 1971 model year. Dates given here are dates of announcement.

Updates of existing models

All-new models

1968

Austin 1800 Mk II

Daimler Sovereign

Jaguar E-type Series II

(XJ6)

Morris 1800 Mk II

Daimler DS420

Rover 3500

Jaguar XJ6

Triumph Vitesse Mk2

Triumph 1 300TC

Triumph 2.5 PI

Wolseley 18/85 Mk II

1969

Austin I800S

Austin Maxi

Leyland Mini

Triumph TR6

Morris 1800S

Triumph 2000, 2500

and 2.5 PI (Mk 2 range)

Wolseley I8/85S

1970

Austin Maxi 1750

Range Rover

Austin Sprite

Triumph Toledo

Rover 2000 and 3500

Triumph Stag

Mkll

Triumph 1500

Triumph Spitfire Mk IV

Triumph GT6 Mk 3

1971

Austin 1100 and 1300

Land Rover Series

Mk III

Morris Marina

Jaguar E-type Series III

Morris 1100 and 1300

Mk III

Rover 3500S

Triumph Dolomite

Wolseley 11 00 and 1300

Mk III

VandenPlas 1300 Mk III

1972

Austin 2200

Daimler Double-Six

Jaguar XJ 12

Morris 2200

Wolseley Six

1973

Daimler Sovereign

Austin Allegro

and Double-Six Series 2

Jaguar XJ6 and XJ 12

Series 2

MGB GTV8

Rover 2200

Triumph 1500TC

Triumph Dolomite Sprint

Triumph Spitfire 1500

1974

Vanden Plas 1500

1975

Austin Allegro 2

Austin and Morris

18-22 series,

and Wolseley Six,

later re-named

Leyland Princess

Jaguar XJ-S

Triumph TR7

1976

Triumph Dolomite

Rover SDI 3500

1300 and 1500

1977

Rover SDI 2300 and 2600

1978

Leyland Princess 2

1979

Daimler Sovereign and

Double-Six Series 3

Jaguar XJ6 and XJ 12

Series 3

Land Rover Stage 1 V8

1980

Leyland Maxi 2

Austin Metro

Triumph TR8

1981

Morris Ital

Triumph Acclaim

Morris Metro van

Range Rover four-door

1982

Austin Ambassador

MG Metro

Rover SDI facelift,

2000 and 2400 SD

models

1983

Jaguar XJ-S 3.6-litre

Austin Maestro

and XJ-SC

MG Maestro

1984

Austin Maestro van

Austin Montego

MG Maestro 2.0 EFi

MG Montego

Rover 200 series

1985

Austin Metro 310 (van)

MG Montego Turbo

BL’s Final Years

Michael Edwardes had been knighted in 1979 by a grateful British government, but he could not be persuaded to stay as the company’s chairman beyond 1982. He felt that he had done what he could to set the company on the right course, and stepped down. In his place came Harold Musgrove as Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of British Leyland, and from 1984 there was also the steadying hand of Sir Austin Bide, who maintained a much lower profile than Edwardes.

By this time, however, the British government was tiring of its commitment to British Leyland, and Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher became determined to sell it off into private ownership. As a first stage, in July 1984, Jaguar Car Holdings was floated off as an independent company on the stock market, and immediately became a thriving business entity under its Chairman John Egan. As a second stage, the remaining elements of the company were renamed as the Rover Group in 1986 when Canadian-born Sir Graham Day was appointed as the new company’s Chairman.

His mission would be to sell off those elements of the company that were not involved in car manufacture – the Unipart spares business and the Leyland commercial vehicles division – and to prepare the Rover Group for eventual privatization. His strategy was to move the company upmarket by focusing on the Rover and MG brands, which were perceived as the two strongest in the company’s portfolio. He also wanted to give the company a younger image, and famously claimed that ‘young people do not want to drive an Austin’. So another long-established British make was clearly destined for a rapid end.

And so British Leyland passed into history, perhaps a shadow of its former self, but certainly in a much better position than it had been when BLMC was formed in 1968. Sadly, in the process of that reconstruction, the heart had also been ripped out of the old British motor industry.