28,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

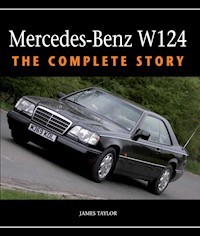

Designed by Mercedes's head of design Bruno Sacco, the W124 range immediately became the benchmark by which medium-sized car models were judged in the late 1980s due to its engineering excellence and high build quality. There was a model to suit every would-be-buyer, from the taxi driver through the family motorist and on to those who were willing and able to pay for luxury and performance. This book covers: design, development and manufacture of all models of W124 including estates, cabriolets and the stylish coupe range; engines and performance; special editions and AMG models and, finally, buying and owning a W124 today. Superbly illustrated with 264 colour photographs.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

Mercedes-Benz W124

THE COMPLETE STORY

JAMES TAYLOR

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2015 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2015

© James Taylor 2015

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84797 954 4

CONTENTS

Introduction and Acknowledgements

Timeline

CHAPTER 1

CONTEXT AND OVERVIEW

CHAPTER 2

DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT

CHAPTER 3

FIRST GENERATION MODELS

CHAPTER 4

FIRST GENERATION FACTS AND FIGURES

CHAPTER 5

SECOND GENERATION MODELS

CHAPTER 6

SECOND GENERATION FACTS AND FIGURES

CHAPTER 7

THIRD GENERATION MODELS

CHAPTER 8

THIRD GENERATION FACTS AND FIGURES

CHAPTER 9

THE AMG 124s

CHAPTER 10

PLATFORMS AND LIMOUSINES

CHAPTER 11

THE AFTERMARKET

CHAPTER 12

SO YOU WANT TO BUY A 124-SERIES MERCEDES?

Appendix – Number Crunching

Index

INTRODUCTION AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Few cars have ever impressed me on first acquaintance as much as the 260E automatic saloon I borrowed from the Mercedes-Benz UK press fleet in 1991. J975 GNV was finished in beautiful metallic Malachite Green, with grey velour upholstery. It came loaded with extras, of course, which would have added nearly £4,500 to the base showroom price of £27,950. But the quality of its construction shone through everywhere, and I was completely sold on the driving experience as well.

Many years later, still a confirmed Mercedes enthusiast, I decided to buy a 1989 300CE to use as a business car. Though it was no longer in the first flush of youth, and at least one of its previous owners had mistreated it, the car was still absolutely superb. I kept it for seven years, and loved every minute of it. Well, almost: I also got to know quite intimately what goes wrong with these cars and how much they cost to repair. Anybody who read my reports on the car in Classic Car Weekly during 2012 will understand what I mean.

So it was more or less inevitable that I would end up writing a book like this. The vast complexity of the 124-series range at times made assembling its history more than a little challenging, and I don’t doubt that one day even more information will be available to swell the 124 story. In the meantime, I need to give special thanks to some of those people who helped out along the way, even though they did not always know they were contributing to the store of knowledge that would one day become this book.

Thanks, then, go particularly to Mercedes-Benz Classic, both for information and for the majority of the illustrations. Thanks, too, go to Mercedes-Benz UK, whose press office kept me regularly informed about changes in the line-up of the 124 series in the 1980s and 1990s. I have absorbed a lot of information from members of the Mercedes-Benz Club in the UK and from its excellent publication, the Gazette, and I have made full use of such material as is available about the 124 range in German. Finally, special thanks to photographer Craig Pusey, who was able to supply a number of excellent pictures, which filled what would otherwise have been gaps in the pictorial record.

James Taylor

Oxfordshire

September 2014

TIMELINE

First Generation

1984 (Nov):

Range announcement:

200D, 250D and 300D diesel saloons

200 and 230E 4-cylinder petrol saloons

200E 4-cylinder petrol saloon for Italy

260E and 300E 6-cylinder petrol saloons.

1985 (Sep):

S124 estates announced at Frankfurt Motor Show:

200TD and 250TD diesel estates

200T and 230TE 4-cylinder petrol estates

300TE 6-cylinder petrol estate.

4Matic announced for all 6-cylinder models; in practice not available until 1987:

260E 4Matic, 300E 4Matic and 300TE 4Matic.

Catalytic converters available as an option on all petrol models.

1986 (Apr):

6-cylinder turbodiesel model introduced for USA only:

300D Turbo.

1986 (Sep):

Catalytic converters standard on all petrol models for Germany; non-KAT models still standard in several export markets (including UK).

1987 (Mar):

Coupé models introduced at Geneva Motor Show:

230CE and 300CE.

1987 (Sep):

6-cylinder diesel saloon made available for markets outside USA; introduced at Frankfurt Motor Show:

300D Turbo and 300D 4Matic.

1988 (Sep):

New ‘clean diesel’ technology announced at Paris Motor Show:

250D Turbodiesel and revised 300D Turbodiesel.

Injection made standard on entry-level petrol models:

200E and 200TE.

ABS made standard across the range.

1989 (Feb):

‘Oblique injection pre-chambers’ for naturally aspirated diesel engines:

200D, 250D and 300D.

1989 (Aug):

Last petrol models made without catalytic converters.

Second Generation

1989 (Sep):

Facelift for full range announced at Frankfurt Motor Show; includes side cladding panels.

Sportline option introduced (not available with 4Matic).

First 4-valve engine introduced:

300E-24, 300TE-24 and 300CE-24.

LWB four-door saloons announced:

250D (LWB) and 260E (LWB).

1990 (Oct):

LHD-only V8 high-performance saloon announced at Paris Motor Show:

500E

1991 (Sep):

Cabriolet model introduced:

300CE-24

Second LHD-only V8 high-performance saloon announced for Japan and USA only:

400E.

1992 (June):

Two millionth 124-series model built.

1992 (Oct):

New 4-valve petrol engines replace earlier types:

200E, 200TE and 200CE (Italy only)

220E, 220TE and 220CE

280E and 280TE

320E, 320TE and 320CE.

Availability of high-performance LHD saloon in Europe:

400E.

Third Generation

1993 (June):

Second facelift, featuring new grille design.

124-series redesignated as E-Class:

E200 Diesel model

E200 and E220 4-cylinder petrol models

E280 and E320 6-cylinder petrol models

E420 and E500 V8 petrol models.

New 4-valve diesel engines:

E250 Diesel and E300 Diesel.

All diesels now fitted with EGR and oxidizing catalyst.

New ‘official’ AMG models:

E36 AMG and E60 AMG.

1995 (June):

W210 announced as replacement medium-sized Mercedes range.

W124 production begins to wind down.

1995 (Aug):

Last 124-series saloons built in Germany.

1996:

Last 124-series estates and last CKD kits for overseas assembly.

1997:

Last convertibles.

These were the sales brochures that persuaded people to buy the 124 models. Those for the saloons and estates were for the UK market in the late 1980s, and came from a central London dealership.

CHAPTER ONE

CONTEXT AND OVERVIEW

The Mercedes-Benz 124 series was one of the most successful car ranges in the company’s entire history. In just over eleven years of production, a grand total of 2,737,860 vehicles were built, in a bewildering array of variants. In the broadest terms, those 2.7 million 124s can be broken down into 2,213,159 saloons, 340,503 estates, 141,498 coupés, 33,952 cabriolets, 2,342 long-wheelbase saloons and 6,406 partially bodied chassis for special-purpose bodies. But those figures tell only a tiny proportion of the story.

By the turn of the 1980s, the Mercedes passenger-car strategy was well established. The company did not have any small or inexpensive saloons in its product range; instead, it concentrated on a single model type that covered a very wide spectrum in the mid-sized sector of the market. By 1980, the company’s hugely respected 123 series embraced saloon, estate, coupé and special-derivative requirements, with engine sizes running from 2 litres at the bottom end up to 3 litres at the top end. Above that came the smallervolume 126-series S-Class, with luxury saloon and coupé models from just below 3 litres right up to 5 litres (and soon, beyond). From these engine ranges were drawn a selection to power the 107 series or SL sports roadsters.

This was the C126 SEC coupé; derived from the S-Class, it set the style for the smaller coupés of the 124 series.

The saloons of the W126 S-Class helped to establish the 1980s style, which the 124s followed.

This product strategy had made Mercedes-Benz the leading car maker in its domestic market of Germany, and had helped it to earn a formidable worldwide reputation as a maker of capable, stylish and durable vehicles. (It should never be forgotten that the Mercedes-Benz car division was just one part of a manufacturing colossus with interests in the heavy and light commercial vehicle markets, the PSV (Public Service Vehicle) market, the aircraft and marine markets and a number of other nonvehicular markets.) Yet by the start of the 1980s, the Mercedes-Benz car division was beginning to feel under pressure from a domestic rival – the BMW company, which had started to become a real force in German car manufacturing during the 1960s. BMW would remain a significant threat to Mercedes-Benz throughout the production life of the 124-series models, and that threat would inevitably have an effect on some aspects of Mercedes-Benz model policy.

With the 124-series range, Mercedes aimed to touch as many bases as possible. This group of 124 derivatives from the late 1980s shows estate, coupé and saloon on the left, with an ambulance on the long-wheelbase platform, a taxi and a police car on the right.

Popularity continues: this line-up was photographed at the first 124 Day to be held by the Mercedes-Benz Club in Britain, in summer 2012.

Of most concern at the start of the 1980s was BMW’s prominence in the compact-saloon sector, where it had built up a solid customer base just below the area in which Mercedes-Benz operated. The focus on fuel economy following the oil crises of the 1970s was already pushing the company towards building a more economical model, and so from 1982 Mercedes decided to take the fight to the enemy and introduced its own compact saloon – the 190 or W201 range. The company saw this very much as an addition to its product range, with the medium-sized cars of the 123 series still being considered the core product.

That strategy would remain in place for the 124 series. Nevertheless, the design and development programme that was necessary to create the W201 range inevitably had some impact on the new 124-series models that were under development at the start of the 1980s. As Chapter 2 explains, a visual resemblance between the W201 and W124 series was just the beginning: there were overlaps of engineering that were of far greater significance. So from the outset, the 124-series range drew not only on the long tradition of medium-sized Mercedes, which at that stage was represented by the 123 series, but also on a wealth of new ideas that had been designed for the new companion-model compact saloons.

The 124 Designation

The designation ‘124 series’ deserves a little explanation. Ever since the amalgamation of the Mercedes marque (owned by the Daimler-Motoren-Gesellschaft) and the Benz marque in 1926, new models had been developed with an identifying code. Until the late 1970s, that code had begun with a capital letter W, which stood for ‘Wagen’ – the German word for ‘car’. The numbers that followed the W had all had three digits since 1945, although there was no discernible logic to their allocation. The predecessors of the 123-series cars had been W114 and W115 models; the 124 series followed neatly from the 123s, but there could not be a 125 series because the code W125 had been used many years earlier for a Mercedes-Benz single-seat racing car. In practice, the successors to the cars of the 124 series were those from the W210 range!

Once a new car entered production, that development code number became part of its public identification – although it was not included in the model name on the boot lid but rather formed an element in the car’s serial number. As model ranges – particularly the 123 series – began to embrace an increasing number of major variants in the late 1970s, so Mercedes decided to use the initial letter of the model code to identify those variants. The W code remained for saloons (so, W124), but over a period of time there were additions: C124 indicated the coupé variant of the 124 series; A124 the cabriolet variant; S124 the estate variant; and V124 the long-wheelbase model (the V was for ‘Verlängert’, German for ‘lengthened’). The special platforms were F124 and VF124 types (the F stood for ‘Fahrgestell’, or ‘chassis’, and the V again for ‘Verlängert’). Elsewhere, the letter R came to designate ‘Roadster’ (as in R107 and R129), although it was not used on the 124-series models which had no roadster derivative.

The R129 sports models introduced in 1989 shared many mechanical elements with the 124-series cars, and were part of the same styling family.

The compact 201-series saloons were positioned just below the 124-series in the Mercedes hierarchy.

On the production line: saloon body shells enter the underbody coating area in the Mercedes plant at Sindelfingen.

Production Jigsaw

Creating a model range as vast as the 124 series was a major achievement for Mercedes-Benz, but it also made for a hugely complex manufacturing operation. The underlying reason for having a range with so many common elements was to minimize manufacturing complexity, but by the 1990s Mercedes-Benz had realized that the sheer number of range variants was working counter to the aim of reducing complexity. The 124 series was the last Mercedes range to embrace such a wide spectrum of different models. Their successors arrived in an era when Mercedes had embarked on a policy of building a larger number of different ranges to satisfy different market niches and to give greater flexibility when product changes were required. So it was that the 210 range replaced the 124-series saloons and estates, while the 208 range replaced the coupés and cabriolets.

The Mercedes-Benz car division still has its headquarters in the Stuttgart district of Sindelfingen, where it had been based for more than half a century by the time the 124 series entered production. In the beginning, the W124 saloons were all assembled here – with the exception, of course, of those shipped abroad as CKD (Completely Knocked Down) kits of parts for assembly elsewhere. From 1990, some assembly work on the 500E saloons was done by Porsche at Zuffenhausen, and then, from May 1992, assembly of W124 variants built for the US market was transferred to a new factory constructed in Rastatt, in Baden-Württemberg.

The C124 coupés and related A124 cabriolets were also assembled at Sindelfingen. The same plant carried out initial assembly work on the V124 long-wheelbase models, although these were then transferred for completion to the Binz factory at Lorch, near Darmstadt in the Hesse region. The S124 estate models, meanwhile, were always assembled at the company’s plant in Bremen, one of the Hanseatic towns in north-west Germany. The Bremen plant also assembled the long-wheelbase platforms for special bodywork, as these were based on the estate models; the platforms were then completed by whichever body specialist had purchased them.

These were the 124 series models that were direct replacements for their 123-series equivalents.

Although the vast majority of 124-series cars were built in Germany, many thousands were built from CKD kits in other countries. For the Central and South American market, assembly was carried out at Toluca in Mexico. From 1992, saloon models for Eastern European markets were assembled at Karczew in Poland, and between March 1995 and 1996, E220 and E250 diesel saloons were assembled at Poona (now Pune) in India for the local market, with engines coming from Bajaj Tempo in the same town.

The platform models of the 124 were used to create special models like this longwheelbase ambulance.

During the production of the 124 series, a fourth body style was created – the cabriolet.

Three Generations

The later chapters of this book look at individual types of the hugely complicated 124-series range, but it will be helpful to provide some context here in the form of an overview. Essentially, the 124 series passed through three major stages of production; here, these are described as the three generations of the range.

The first generation began with the cars that were announced in autumn 1984 as ‘1985 models’ (Mercedes model years normally run from autumn to late summer and are named after the later of the two relevant calendar years). The models were not all introduced at once, but arrived gradually between 1985 and 1987. This first phase of the 124 story ended in summer 1989.

The second generation of the 124 models began with the 1990 models introduced in autumn 1989. These second-generation cars were characterized by a mild facelift, but there were further progressive changes over the next three years. Long-wheelbase and cabriolet models arrived in this period, and so did new 4-valve petrol engines. Production of these second-generation cars ended in summer 1993.

The third-generation cars were introduced in autumn 1993 as 1994 models. They came with a further facelift (notably a new grille design) and a series of new model designations; at this point the cars took on the E-Class name. Mercedes’ acquisition of a controlling interest in AMG also led to the first ‘official’ AMG high-performance models. Production then began to wind down in summer 1995 as the replacement 210-series cars were announced, but the changeover to the new models was gradual – CKD kits for India were built until June 1996, the S124 estates remained in production until 1996, and the last A124 cabriolets were not built until 1997.

Engines Strategy

By the 1980s, it was established Mercedes-Benz strategy to overlap the introduction of new car models and new engine ranges. So a new car range would initially be introduced with slightly improved versions of the engines from the range it replaced. This avoided the huge costs of changing both engines and car architecture at once, and it also reduced the risks if problems developed: at all points in the production cycle, either engines or structures had been in production for some years and were therefore likely to be trouble-free. Typically, a Mercedes model range might last for ten years, and new engines (often accompanied by a facelift) might be introduced somewhere around the midpoint of the range’s production life.

However, things were a little more complicated for the 124-series cars. Even though most of the engines available at the start of production were carry-overs from earlier models, the new 6-cylinder engines had never been seen in production models before. They therefore brought with them an element of risk, although in practice Mercedes had every confidence in them because their basic design had already been proven in the related 4-cylinder petrol types that had been in production for five years.

The big range of engines on offer as production got under way was a very clear illustration of Mercedes’ policy for the 124 series which, as already explained, was intended to cater for as many different customer requirements as possible. By the mid-1980s, there were still several car makers who had not embraced diesel power, but Mercedes had been a pioneer of diesel engines in passenger cars and continued to offer a range of diesel engines alongside its petrol types. Even so, public acceptance of diesel engines was not as widespread as it is today: some thirty years ago, diesel engines were always seen as the poor relations.

The least powerful diesel engine was a 2-litre, 4-cylinder type, which was unashamedly aimed at the taxi market where economy and durability were considered much more important than refinement and performance. Next up the diesel range, a 5-cylinder unit was favoured for engines between 2.5 and 3 litres; this configuration had come about largely for historical reasons, and the basic engine was later supplemented by a turbocharger to give additional performance. The full 3-litre engine was then a 6-cylinder unit, again with a turbocharger when performance was an important consideration.

Right at the bottom of the petrol range – although some way above the similarly sized diesels in terms of prestige – were 4-cylinder engines, the baseline being a capacity of 2 litres or thereabouts. In practice, the entry-level 124-series models initially had carburettors, which was old-school technology when the rest of the range had fuel injection, although they did take on injection systems later. Up to 2.5 litres, it was Mercedes policy to stay with 4 cylinders (this was an area where rival BMW saw its chance and scored with small-capacity 6-cylinder engines).

Above 2.5 litres, Mercedes policy was to use 6-cylinder engines, which in this period were always in-line designs rather than the V6 types favoured in the later 1990s. A size of 3 litres was seen as the upper extent of the medium range, and beyond that was V8 territory, where Mercedes started with a 3.5-litre size in its S-Class saloons and SL roadsters. Nevertheless, as time went on and more was expected from the 124-series range, the upper size limit of the 6-cylinders was extended to 3.2 litres (and AMG took it to 3.6 litres). In later years, there would be 4.2-litre and 5-litre V8s in special high-performance variants of the 124 series, too.

A Benchmark

Mercedes’ hugely respected 123 series built between 1976 and 1985 was a very hard act to follow, but the 124-series cars did the job with aplomb. For most of their production life, they set the standard for other makers of medium-sized saloons, and that overall standard was simply too high to be equalled, although some makers equalled or surpassed aspects of it towards the end of the 124 series’ life.

There is also no doubt that the 124 models were the last of their kind. They had been designed and engineered at a time when Mercedes had believed its engineers knew best, and as a result they lasted exceptionally well. The new philosophy that swept through the Mercedes car division in the early and mid-1990s placed a greater emphasis on meeting the customer’s whims and on building down to a price. The new E-Class, the 210 series introduced in 1995, would be a very different kind of car.

This was the range of cars that the 124s had to replace – the hugely successful 123 series, which came as coupé, saloon and estate. There were platform derivatives for specialist coachbuilders, and long-wheelbase models too.

Professional road testers are notoriously hard to please, not least because they have driving experience of a far wider variety of cars than the typical customer. As quotations from contemporary road tests make clear later in this book, the 124 series was held in very high respect throughout its production life. For the moment, however, a single comment will suffice. It was made by the US magazine Road & Track in its April 1986 issue: ‘This may well qualify as the outstanding 4-door sedan available in the world today.’ Praise rarely comes higher.

Like their predecessors, the 124-series cars were renowned for their durability and longevity. This 300D saloon, pictured on display at the Mercedes-Benz Museum in Stuttgart, had covered over a million miles as a taxi in Portugal. WIKIMEDIA COMMONS/STEPHEN HANAFIN

EXPERIMENTAL ENGINES

The search for viable alternatives to petrol and diesel engines for road vehicles has intensified in recent years, but Mercedes had begun to look at the possibilities by the 1980s. That was the period when the 124-series models had entered production and were at the heart of the company’s passenger-car range, and so it was natural that they should be used as the basis of experiments.

At least two cars were converted for experiments with alternative fuels. One car was fitted with a gas turbine engine, and the second was a 230E converted to run on hydrogen stored in a special tank in the boot.

There was never any real question of either experiment becoming a production reality during the production life of the 124 models. The lessons learned from them simply went into the company’s knowledge bank for use in the future.

Also purely experimental was this gas turbine-powered 124 model.

This was the experimental hydrogen-powered 230E. Note the special filler arrangements. Even though this was only an experimental car, Mercedes provided special badges for the boot lid: ‘Wasserstoff’ is German for hydrogen.

The hydrogen-powered car retained its original 4-cylinder engine, with modifications. The fuel was stored in a special tank that occupied a lot of room in the boot.

AN AFTERLIFE IN KOREA

After the 124-series models went out of production at Mercedes-Benz, their design was licensed to the SsangYong Motor Company of South Korea to give that company its first saloon car. The front and rear end details were redesigned to give a more modern design with a SsangYong flavour, and the wheelbase was extended by around 100mm to 2,900mm (114.2in). The car entered production in 1997 at the SsangYong factory in Pyeongtaek as the SsangYong Chairman, using the 2.2-litre M111 4-cylinder engine and the 2.8-litre and 3.2-litre M104 6-cylinder engines. Standard transmission was the Mercedes-Benz 5G-Tronic automatic.

In 2003, the Chairman was facelifted with a restyled grille, different front and rear lights and an enhanced interior. By 2005, the car was available with rear parking sensors, rain-sensing wipers, ABS and a suite of stability and traction controls, plus electrically adjustable rear seats and heated and cooled cup holders.

Between 2007 and 2008, a 279PS 3.6-litre engine was available; known as the XGi360, this was a new development of the 6-cylinder engine, with a 3598cc swept volume and type code 104.941, and was not the same as the 3.6-litre AMG engine used in the later 124-series cars. In 2008, a completely different model was introduced with the Chairman name, but the old model remained in production, now designated Chairman H to distinguish it from the newer Chairman W. There was a further redesign in 2011.

The SsangYong Chairman was available outside South Korea but sold poorly. In some countries it was rebadged as a Daewoo Chairman to take advantage of the Daewoo dealership network, and in North Korea it was rebadged as a Pyeonghwa Junma.

CHAPTER TWO

DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT

New-model development is a continuous process at large car-manufacturing companies like Mercedes-Benz. Work on the model that would replace the 123-series mediumsize saloons introduced in 1976 had already begun before those cars reached the showrooms. The new cars took on the 124-series name and from the outset were conceived as direct replacements for the old models.

This was a particularly interesting time for the Mercedes-Benz car division. Traditionally, the entry-level Mercedes-Benz had been the cheapest version of its medium-size saloon family, but the impact of the fuel price rises during the 1973–74 oil crisis brought about a major change in thinking at the top level of the company’s management. Fuel was not going to get cheaper, so cars would have to use less of it if they were to remain viable, and the most obvious way of achieving this aim was to build smaller and lighter cars. So, as already explained in Chapter 1, planning began in 1974 for a small Mercedes that would become the new entry-level model. That would reach the market in 1982 as the W201 or 190 model.

The plan for this new model was that it would make the Mercedes brand available at a lower entry point, but inevitably there would be more expensive variants that would nudge against and maybe even overlap with the basic models of the medium-size saloon range. So the plan for a third tier in the Mercedes saloon range (the top model would remain the S-Class) had an impact on the conception of the 124-series cars that would be introduced a few years after it reached the showrooms. However, much needed to be discussed and more detailed planning would be necessary before the relationship between the two model ranges could be finally settled; in particular, how much engineering could be shared between the two of them.

In the meantime, autumn 1976 saw the first preparatory sketches for the 124 series being drawn up in the styling department at the Mercedes-Benz plant in the Stuttgart district of Sindelfingen. That department was newly under the leadership of Bruno Sacco, who had replaced Friedrich Geiger in 1975. Part of Sacco’s brief was to establish a new style for the Mercedes-Benz models of the 1980s, and it was a formidable task. First had to come the new S-Class models, scheduled for launch in 1979, and their coupé derivatives that would arrive in 1981. A year after that, Sacco’s team had to have the new W201 compact saloons ready. The 124 series’ medium-size saloons would be third in line, and had to be ready for introduction in 1984.

So all three ranges were to some extent designed at the same time. The W126 S-Class models that made their debut at 1979’s Frankfurt Motor Show were a striking demonstration of the way Sacco would play things. Simpler and less ornate than the cars they replaced, they were nonetheless quite clearly members of the Mercedes family. Later, Sacco would explain his theory of vertical and horizontal integration in the design of a manufacturer’s products. By vertical integration, he meant that new models were visually linked to earlier ones on the manufacturer’s timeline, and by horizontal integration he meant that all contemporary products had a family resemblance. That was exactly what he set about achieving with the 126-series S-Class, the 201-series compact saloons, and the 124-series medium-size range.

The Challenge

In looking at the engineering and design that went into the new medium-size Mercedes, it is easy to overlook the scale of the project. It was simply massive, and probably only a company with the vast resources of Mercedes-Benz would even have attempted to take it on. Getting the 124-series cars into production consumed huge amounts of the resources available to Mercedes-Benz, but the company prided itself on efficient solutions to problems and worked steadily through all the issues that arose until a plan was in place. It was inevitable that there would be hiccups, but these would be dealt with as they arose, efficiently and quickly.

Fundamental to the difficulties was that the new 124-series cars would be made in such a large number of variants to suit an enormously varied group of potential customers. Not only would there be saloon, estate and coupé variants, plus special platforms for aftermarket bodywork. There would also have to be multiple sub-variants of most of those variants, to suit such things as increasingly demanding emissions and crash-safety regulations in the United States. At least some models would have to be suitable for assembly from CKD kits outside Germany. Nobody doubted that, even if the programme had been thought through carefully down to the last detail, changing circumstances would demand extra variants that would have to be designed on the hoof.

The sheer scale of such a programme demanded careful and detailed production planning, and a key member of the team that delivered the 124 series was production director Werner Niefer. It was his job to make the most efficient use possible of the various Mercedes-Benz assembly and production ‘feeder’ factories around Germany. It was his decision to build new paint and metal-pressing shops at Mercedes’ Sindelfingen works so that the production system could cope. It was his team who coordinated the suppliers of bought-in parts, such as electrical specialist Bosch and gearbox specialist Getrag. Above all, it was Niefer’s job to fit these new 124-series cars into a production jigsaw alongside other Mercedes-Benz cars that would be in production during the 1980s – the S-Class saloons and coupés, the SL roadsters, and the planned compact saloons of the W201 range.

Looking back, it is a remarkable tribute to the Mercedes-Benz of the 1970s and 1980s that the company was able to pull off such a vast project. It was an enormous challenge – but, in so many ways, it marked the end of an era. As Chapter 1 has explained, the 124 series would not be replaced by a single model range, but by several, as the Mercedes-Benz car division embraced greater production flexibility.

Engineering

Although some elements of the Mercedes model strategy for the 1980s had been initiated under Hans Scherenberg, who was running passenger-car development when Bruno Sacco became the new head of design, matters were not firmed up until Werner Breitschwerdt had taken over the development post in 1977. In July that year, Breitschwerdt settled the exact dimensions of the new 124-series models, and that of course gave Sacco’s team a more precise set of aims. Just under a year later, in April 1978, Breitschwerdt took the decision that the 124 series should share as much as possible of its running gear with the 201 series. This had probably been an inevitable decision ever since the smaller model range had been conceived, but it had now become formalized and would have a very great impact on the way the 124 series would turn out.

One thing that had been clear for some time was that the rear suspension of Mercedes saloons needed a new design. As performance improved, so the limitations of the longstanding swing-axle layout became more and more apparent and, although modifications had been introduced on more than one occasion to improve the basic design, Mercedes engineers felt they had reached the limit. So they started work in the first half of the 1970s on a new design that would take the company through the 1980s and beyond.