35,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

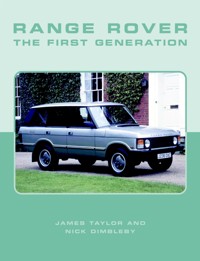

The Range Rover's designers intended it to be a more comfortable and road-friendly passenger-carrying Land Rover, but customers quickly saw something much more in it. During the 1970s, while its immense practicality and capability were appreciated and acknowledged, a Range Rover became a sought-after and prestigious possession. It went on to change the face of Land Rover for ever. Range Rover First Generation - The Complete Story delves into the real story of the Range Rover, examining what lay behind the multiple changes in its twenty-six years of production. The book covers the full development story; custom and utility conversions; Range Rovers for the US market; full technical specications and Range Rovers assembled overseas. If ever a car deserved the over-used epithet 'iconic', the first-generation Range Rover is it.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

RANGE ROVER FIRSTGENERATION

THE COMPLETE STORY

James Taylor

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2018 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2018

© James Taylor 2018

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of thistext may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 412 4

CONTENTS

Timeline

Introduction and Acknowledgements

CHAPTER 1ORIGINS AND DEVELOPMENT

CHAPTER 2ON THE SURFACE, 1970–79

CHAPTER 3GOOD INTENTIONS: BEHIND THE SCENES IN THE 1970s

CHAPTER 4WINDS OF CHANGE: THE 1980–84 MODELS

CHAPTER 5EMBRACING LUXURY: THE 1985–89 MODELS

CHAPTER 6A HOLDING OPERATION: THE 1990–94 MODELS

CHAPTER 7AIRBAGS AND CLASSICS: THE END OF AN ERA

CHAPTER 8TRANSATLANTIC CONQUEST

CHAPTER 9CONVERSIONS: UTILITY TYPES

CHAPTER 10LUXURY, LEISURE AND LENGTH

Appendix I: Buying and Owning a Range Rover

Appendix II: Range Rovers Built Overseas

Appendix III: Vehicle Identification

Index

TIMELINE

1970

Two-door model introduced; V8 engine only; PVC upholstery.

1973

Brushed nylon upholstery available, optional at first.

1981

Four-door model joined two-door; fabric upholstery standard.

1982

Automatic gearbox (Chrysler three-speed) became optional.

1984

Injected V8 became available, initially on Vogue models only.

1985

ZF four-speed automatic replaced Chrysler three-speed.

1986

First diesel option: 2.4-litre made by VM, manual gearbox only.

1988

First Range Rovers with leather and wood interiors (Vogue SE); V8 engine enlarged to 3.9 litres for US market only.

1989

V8 engine enlarged to 3.9 litres for other markets; VM diesel enlarged to 2.5 litres.

1992

Air suspension replaced coil springs on top models; long-wheelbase model added to range as Vogue LSE (called County LWB in USA); 200Tdi diesel engine replaced VM type.

1994

Completely revised dashboard with airbags for driver and passenger (March); long-wheelbase models discontinued and standard-wheelbase renamed and badged Range Rover Classic; more refined 300Tdi diesel engine.

1996

Last of the first-generation Range Rovers built.

INTRODUCTION AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This book tells the story of a four-wheel-drive vehicle that was intended as a more comfortable Land Rover and ended up as a motoring phenomenon. Although it has long since been replaced by newer models wearing the same name, their success would have been impossible without the foundations that this one established.

My own admiration for the Range Rover is enormous, and so is my admiration for the engineers and designers who gradually turned it into a luxury car by small steps over its long production life. Enormously characterful as well as capable, it set the standards not only for its competitors but also for its successors to follow. If any car deserved the title of ‘classic’, this one did, and Land Rover’s decision to call the run-out model by the name of Range Rover Classic was entirely appropriate.

Like all good myths, the ones that have grown up around the Range Rover present a very simplified version of the real story. So this book attempts to tell what really happened, warts and all. Some of it is the best that can be achieved at present – more information will certainly emerge in the future – but it does attempt to go further and deeper than any books about the Range Rover have done before.

A large number of people have contributed to the information in these pages. Many of them have been enthusiasts, and many have been employees of the Rover Company or of Land Rover Ltd. I have been lucky enough to know and interview many of the engineers and designers who were involved with the Range Rover over its quarter century of production, and also to talk to some of those aftermarket specialists who produced conversions and modifications. There just isn’t room to list all of them here, even if I could remember all of their names. So I will simply say a big thank you to everybody who has contributed to the fund of knowledge that has made this book possible, and I will add that anybody who can provide more information (or correct what is here) is very welcome to contact me through the publishers.

James Taylor

Oxfordshire

October 2017

CHAPTER ONE

ORIGINS AND DEVELOPMENT

There is no denying that the very name of Range Rover has a powerful appeal, suggesting an ability to travel at will over wide open spaces. But the car that became the Range Rover started out with a much humbler name. In fact, when first proposed during 1965, it was just another Land Rover.

The Land Rover, introduced in 1948, had become a huge success for the Rover Company that made it, rapidly overtaking its traditional saloon cars as the best-selling product. During the 1950s it became the foundation of the business, although Rover people still tended to think of themselves as a car company first and foremost, with a profitable sideline in light commercial vehicles.

One group of Rover employees who were more aware of the truth than most was the Sales Department, and by the turn of the 1960s they were beginning to pile on the pressure for a related product line to sell alongside the Land Rover. The cars side of the business had two models – the P4 and P5 Rover saloons – so why should the Land Rover side not have the same? Several ideas were put forwards, ranging from bigger Land Rovers that were more like small trucks, down to minimalist economy models, but none had progressed beyond the prototype stage. Except, that is, for a long-wheelbase Forward Control model introduced in 1962, and that was a slow seller.

A BRIGHT IDEA

Against this background, it is not surprising that one of Rover’s more fertile minds came up with a new idea. Spen King – Charles Spencer King – was a nephew of Rover’s Chairman Maurice Wilks, and of its former Chairman Spencer Wilks, the brothers who had guided Rover’s fortunes since the 1930s. He had joined Rover to work on gas turbine engines after an apprenticeship at Rolls-Royce, and had gone on to have significant input into the revolutionary new Rover saloon that was introduced as the Rover 2000 (known internally as P6) in 1963. He had since become head of Rover’s think-tank department, called New Vehicle Projects, whose job was to develop new ideas that might one day become new products. New Vehicle Projects was quite independent of the mainstream Engineering Department, which gave it greater freedom to innovate.

Spen King is often described as a very serious and boffin-like individual, but he also had a great sense of fun. Here he is in 1966 at Eastnor, clearly enjoying the opportunity to take photographs from the bonnet of a 109-inch Land Rover Station Wagon.

The Rover 2000 was introduced in 1963 and featured long-travel coil-spring suspension. Spen King realized that this would work on a Land Rover, too.

King reasoned that it should be possible to improve on the traditionally harsh ride characteristics of the Land Rover by using softer suspension with long-travel coil springs in place of the leaf springs that had been standard since 1948. He proved it to his own satisfaction by driving a Rover 2000 – which had such springs – across a rough-surfaced field. And from that simple thought came the idea that long-travel coil springs might form the basis of a much more comfortable passenger-carrying Land Rover – the sort of model that was then thought of as a Land Rover Station Wagon.

The next stage was to share these ideas with two of his colleagues. One was Peter Wilks, Rover’s Technical Director and another nephew of the Wilks brothers; he and King were cousins. The other was Gordon Bashford, the chassis designer on the New Vehicle Projects team who had been responsible for the chassis and suspension designs of every new Rover car since the 1930s. Peter Wilks could see the potential in King’s idea, and agreed that he should spend some time developing it. So King and Bashford set to work on preliminary layout drawings, ending up with a five-seater passenger-carrying Land Rover that would combine all the rough-terrain ability of a Land Rover with the comfortable ride and modern driving dynamics of the latest Rover cars.

A key innovation in these preliminary drawings was the incorporation of disc brakes. The Rover 2000 had disc brakes all round and had been highly praised for them. Land Rovers, by contrast, had drum brakes all round – which were adequate for a relatively slow vehicle, but not for one with the sort of road performance that King and Bashford envisaged for their new design. In an interview with the author some twenty-five years later, Gordon Bashford remembered that the original plans were drawn up around the biggest engine that Rover then had available, which was the 2995cc straight-six then in production for the Rover 3-litre saloon. It had been tried in detuned form in experimental Land Rovers, when it gave about 110bhp. Bashford also remembered that when he had completed the preliminary layouts, the wheelbase dimension worked out at 99.9in, and that he and King subsequently decided to round it up to 100in for convenience.

CHANGING DEMANDS

Meanwhile, Rover’s Managing Director, William (Bill) Martin-Hurst, was taking a very keen interest in improving the lacklustre sales of Rovers and Land Rovers in the USA. He had appointed a new team to run the Rover Company of North America (RCNA) from 1962, and he listened carefully to what they told him about the mismatches between US customer expectations and Rover’s existing products. As part of his attempt to get a better understanding of the US car market, he sent his market research manager, Graham Bannock, on a tour of the USA in summer 1965. When Bannock returned to his office at Rover’s Solihull works, he set about producing a comprehensive report on his findings.

The report was several months in the writing, and was finally distributed on 20 July 1966. Graham Bannock remembered in a 1993 interview that

…the real growth was coming from people who were buying Land Rovers to tow caravans, to go on holiday, by architects and surveyors who have to go across rough country… by people who were living in suburban houses but wanted to project the kind of image that most 4×4 buyers today want to project, of being real country types.

Land Rovers were not alone in catering for this emerging trend, of course, and further research showed that it was a trend that was emerging globally, and was not confined to the USA alone. Some US domestic manufacturers were already building vehicles that catered partially for it, such as the International Scout (introduced in 1961 and really a multi-purpose small farm truck) and the Jeep Wagoneer (introduced in 1963 and really a big passenger-carrying Jeep styled to look like an American station wagon or estate car).

That something new was happening had become clear when Ford had jumped on the bandwagon in 1965 with their new model, called the Bronco. This incorporated elements of the traditional workhorse 4×4 but was deliberately more comfortable, and was deliberately slanted towards outdoor leisure activity use – towing boats, carrying sports equipment, and getting to places where cars could not go, but without the truck-like qualities of traditional 4×4s.

Not surprisingly, one of the recipients of Bannock’s report was Spen King in the New Vehicle Projects department. At the time he was writing it, Bannock confirmed in 1993 that ‘I was not aware of the fact that Spen was already working on this vehicle.’ And yet, by an astonishing and fortuitous coincidence, the report recommended that Rover should look at developing ‘more or less what Spen and Gordon had already come up with – the vehicle concept.’

That coincidence caused a certain amount of excitement within New Vehicle Projects. It also helped to tip management opinion at Rover in favour of the new Land Rover that New Vehicle Projects were working on. Technical Director Peter Wilks had been supportive of the concept, but had also been undecided about its merits. He now became convinced that King and Bashford were on to something, and approved further work on it. So although they had no formal engineering budget, King and Bashford were now authorized to build a first prototype. All this was still going on within New Vehicle Projects; the mainstream Land Rover engineering teams were not involved because the project had purely research status at this stage.

A NEW ENGINE

In the meantime, there had been other changes at Rover that would feed into Spen King’s new idea. Bruce McWilliams, head of the Rover Company of North America, had made clear to Rover’s MD Bill Martin-Hurst that a major hindrance to Rover sales in the USA was a lack of power. This was a particular problem with Land Rovers: in an interview with the author in 2003, McWilliams explained that it was common for US Land Rover owners to tow their vehicles on an A-bar behind a car or pick-up to wherever they planned to go off-road driving, because the Land Rover was so slow on the road. So McWilliams suggested that he should see whether any American car makers would be prepared to sell V8 engines to RCNA to create a more powerful US-model Land Rover. Martin-Hurst told him to see what he could find.

During 1963, McWilliams located a Chrysler engine that might have been suitable, but before negotiations with Chrysler began, Martin-Hurst himself came across a better option. He was in the USA to negotiate a deal to sell Land Rover diesel engines for use in fishing boats, and at the workshops of Mercury Marine he saw a small aluminium-alloy V8 that the company intended to try out in a power boat. Learning that it was a General Motors design and had just been taken out of production that summer, he measured it up and realized that it was just the right size for Rover cars as well as Land Rovers. This engine would do far more than provide extra power for Land Rovers sold in the USA: it would meet all of Rover’s medium- and long-term needs for both cars and Land Rovers at a stroke.

The 215cu in V8 in its original Buick form; the one pictured was one of those that was delivered to Rover – it might even be the very engine that William Martin-Hurst had shipped over from Mercury Marine.

To cut a long story short, by January 1965 Martin-Hurst had arranged a deal under which Rover would take on a manufacturing and development licence for the Buick 215 V8 engine. Work on other new engines at Rover had stopped, and for the next eighteen months the company’s engine department would be working flat out to adapt the all-alloy Buick V8 for British manufacturing methods and British requirements. This was clearly to be the engine of the future at Solihull (it was first introduced in an up-engined Rover 3-litre called the 3.5-litre in autumn 1967), and Spen King and Gordon Bashford recognized that it would be perfect for their new Land Rover station wagon. So the 3.5-litre V8 replaced the 3-litre straight-six in their layout drawings, probably late in 1966. It would go on to become one of the key elements of the vehicle that became the Range Rover.

THE FIRST PROTOTYPES

In the summer of 1966 Peter Wilks authorized work to begin on developing the new 100-inch Station Wagon. To that end, he seconded an experienced Land Rover engineer to New Vehicle Projects to help with the preliminary stages. This man was Geof Miller, who had been running mainstream Land Rover development. This was an astute choice: when news of what was going on within New Vehicle Projects leaked out to the Land Rover engineers, many reacted very negatively, and among the biggest sceptics of fitting coil springs to a Land Rover was the division’s chief engineer, Tom Barton. But Miller’s experience in traditional Land Rover engineering lent a very welcome sense of reassurance to the proceedings.

One of Geof Miller’s first jobs was to examine competitors’ vehicles, and he gathered together a number of examples in late 1966, including such vehicles as an Austin Gipsy, a Ford Bronco and a Toyota Land Cruiser. He also realized that it would help all those likely to be involved in the design and development of this new vehicle if they had some hands-on experience of the way it was likely to be used; most of the New Vehicle Projects team were car men, rather than Land Rover men, and did not have the relevant experience.

So, aided by young engineer Nick Wilks (son of Rover’s former Chairman Spencer Wilks), he organized a pair of assessment days for senior staff during October and November 1966 at Eastnor Castle in Herefordshire, where Land Rover had an arrangement to test its vehicles off-road. A day’s worth of serious off-road driving probably opened the eyes of quite a few of those who attended – although of course some of them were too senior to be able to admit it!

Officially described as ‘benchmarking’ trials, the two days at Eastnor in autumn 1966 allowed senior Rover people to get to grips with what was expected of a Land Rover. Transmissions chief Frank Shaw is driving the lead vehicle here – an experimental prototype with a V8 engine. At the back of the queue are the Ford Bronco and a Nissan Patrol.

The new 100-inch Station Wagon was formally mentioned for the first time in the Rover Board minutes for January 1967, when development was said to be ‘proceeding’. By this stage, some initial costings had been done, and a provisional estimate of £1,750,000 was recorded. The earliest practicable introduction was noted as the end of 1969. The early months of 1967 saw Gordon Bashford refining his design drawings, and there was a brief flirtation with the idea of using leaf springs to simplify axle location and reduce costs, but that came to nothing. On one notable occasion, Managing Director William Martin-Hurst dropped in to New Vehicle Projects to review progress. After examining the latest schemes, he commented, ‘You do realize that you’ll have to do a pick-up version of this as well later on?’ As a result, Gordon Bashford altered his drawings and made the chassis frame ½in (13mm) deeper to provide extra strength. That extra depth remained in the Range Rover’s specification throughout its life.

From this period also came a plan to widen the vehicle’s appeal by having a two-model range, the cheaper version with a 4-cylinder engine and the more expensive with the V8. Initially Bashford suggested that the 4-cylinder might be the 90bhp engine from the Rover 2000 saloon, but his later thoughts focused on the 2.25-litre Land Rover engine. Engineer Roger Crathorne remembers a drawing pinned on the wall in the office used by the 100-inch Station Wagon team, showing it with a bulge in the bonnet. This might well have been a draft scheme to make room for a 4-cylinder engine, but no 4-cylinder prototype was ever built. Even so, the ‘economy model’ remained an element in management policy discussions until it was abandoned at the end of 1968.

Spen King wanted the new Land Rover to be bolted together from flat sections that could be easily packed for shipping and assembled overseas. He also wanted a two-door body for additional strength. This schematic drawing shows how the body frame would be constructed.

From the start, the 100-inch Station Wagon was intended to have only two doors. The main reason, as Spen King told the author, was to give additional strength to the body shell, but it was also true that the Ford Bronco, which New Vehicle Projects had studied, was a two-door design – and so was the International Scout. King asked Rover’s chief stylist David Bache to draw up an appropriate shape for the new vehicle, but the Styling Department was too busy on other projects at the time, so King and Bashford roughed it out themselves. Both freely admitted later that they had managed to secure some unofficial, out-of-hours help from Geoff Crompton, one of David Bache’s team.

Meanwhile, Peter Wilks had formally appointed Geof Miller as Project Engineer for the 100-inch Station Wagon, and Miller assembled his development team. Nick Wilks moved on to another task, and so the team was completed by Alan Wood as Assistant Project Engineer and by Roger Crathorne as Technical Assistant. Alan Wood was an experienced engineer; Roger Crathorne was fresh from completing an apprenticeship on the Land Rover side of the Rover Company.

This team began to build a first prototype in early summer 1967, arranging for parts to be made by hand, and calling on expertise from other departments at Solihull as they needed it. The body was built up in the Jig Shop, and final assembly took place in the Experimental Department. Prototype 100/1 had reached running condition in early July, and by deduction the date seems to have been 7 July. Roger Crathorne remembers that the cooling team from the Research Department pulled rank on him and ‘borrowed’ it to try out that very evening. They took it to the MIRA test track where it achieved 100mph on the banking on its very first high-speed runs. A minor problem was that the exhaust became so hot in the process that it set the carpets alight, so Crathorne’s job the next day was to design a heat shield!

This is one of the official pictures of 100/1. The basic lines were already in place, but would be very much refined later. BRITISH MOTOR INDUSTRY HERITAGE TRUST

Prototype 100/1 was very much a Land Rover in conception. Its chassis side members were assembled from four pieces of flat steel welded together at the corners, just as was standard Land Rover practice. It had a Land Rover gearbox and selectable four-wheel-drive system, Land Rover axles, Land Rover drum brakes all round, and its bodywork was, frankly, rather crude even if it did have a certain elegance. Some elements of the vehicle were not Rover at all: Roger Crathorne remembers being sent to the local Ford dealer to buy a set of Transit van bumpers, which were just the right size for fitting to the 100-inch prototype.

Graham Bannock beat Rover’s official photographer to take the first picture of the first prototype. Peter Wilks is driving, while Spen King is sitting on a wooden box beside him because there was only one seat.

The chassis of 100/1 was built like a Land Rover’s, with four flat plates welded together at their edges. The gearbox was a Land Rover type, and the transfer box gave selectable four-wheel drive.

A major factor in the success of the new vehicle would be the 3.5-litre V8 engine, which had not yet entered production for Rover cars. The one in 100/1 was a development engine, probably based on a Buick block.

Although 100/1 was immediately pressed into service as a test vehicle, it did not go through the usual Land Rover pavé and cross-country durability cycle. The design was moving on rapidly, and a second prototype was built between February and May 1968. This was built with left-hand drive and had a number of improvements. The chassis frame was stronger, its side members each being assembled from two C-section pressings welded together – a method of construction that had been used on Rover cars since the late 1940s. Roger Crathorne remembers Gordon Bashford and Spen King talking about this, but neither he nor Geof Miller realized at the time that the idea came from Rover cars.

Equally important were changes to the suspension and brakes. On the first prototype, the front suspension had been copied from that on the Ford Bronco, but it gave quite unacceptable levels of kickback and bump-steer. So for 100/2, Gordon Bashford’s assistant, Joe Brown, redesigned it with a Panhard rod to control the lateral movement of the axle. On the rear axle, a Boge Hydromat self-levelling strut was added to keep the ride height constant when the vehicle was laden; the only other way to achieve this was to fit very stiff rear springs, which would have ruined the unladen ride. This second prototype also had the four-wheel disc brakes that Spen King saw as essential, and its function was to prove the soundness of the basic design, which it did. ‘This time,’ Spen King remembered many years later, ‘we knew we had got it right’.

SB Wilks had retired by the time the 100-inch was under development, but he had been made Rover’s Life President. Prototype 100/1 was delivered to him at his home on the Scottish island of Islay for assessment.

One thing they did not yet have right was the transmission. Spen King was concerned that the heavy axles that were needed to cope with the torque of the V8 engine would spoil the ride quality of the new model. Geof Miller remembered that Rover had experimented with a permanent four-wheeldrive transmission some ten years earlier, and suggested that such a system would divide torque between the front and rear axles and so eliminate the need for a heavy rear axle. He found that transmission in the stores, and had part of it built into prototype 100/2 to prove his theory.

Also needed was a new gearbox, because the existing Land Rover type was not strong enough. As it happened, a new forward-control military Land Rover was also under development at Solihull: it, too, was to have the V8 engine, and it, too, needed a new gearbox. Frank Shaw, head of the Transmissions Department, was persuaded to cater for both requirements with a single design, but a quarter of a century later he admitted to the author that he wished he had not done so. The rugged, heavy-duty military gearbox with its integral two-speed transfer gearbox was really not at all suitable for a supposedly civilized Land Rover station wagon, and the LT95 four-speed gearbox would always be one of the less attractive features of the early Range Rover.

By the time of this picture, 100/1 had acquired some unbadged hubcaps, borrowed from the out-of-production Rover P4 saloon range. It was lined up here with a pair of Land Rovers to make sure it fitted in with the overall look of the range.

MARKET RESEARCH

Meanwhile, Graham Bannock had set in motion a market research programme to check whether Rover were on the right track. His questions were passed on to an agency that conducted a survey in Britain over the early summer of 1967. For the purposes of the survey, the new Land Rover was known as Concept Oyster, and interviewees were shown some early concept sketches in order to gauge its size and general appearance. Bannock remembers that the research was carried out in two stages, and that interviewees were told only in the second stage that the vehicle would be a Rover. It is an interesting reflection on the company’s standing at the time that the association with Rover produced far more positive reactions.

One of the pictures that the Project Oyster interviewees were shown. The paper sketch of the planned new model was pasted on to a picture of a Land Rover and a Mini to give an idea of the intended size.

The information given to Oyster interviewees sheds further light on the way Rover saw their proposed new vehicle at this stage:

Oyster is not a converted passenger car but a purpose-built estate car with a unique combination of features. It will offer safe, fast and relaxing travel on motorways, on the road, across fields, sands, snow or ice. It is easy to drive and handle, will tow boats or caravans, carry milk churns, be used as a camping vehicle or you can use it to go shopping or to go to the opera. Many extras from roof-racks to winches to air-conditioning will permit the owner to adapt the vehicle for his own special requirements.

The interviewees were also told that there would be a three-speed automatic gearbox as an alternative to the standard four-speed manual.

CREATING A STYLE

In summer 1967, David Bache finally found time to look at the 100-inch Station Wagon and to propose some designs. His first ones in June 1967 were very car-like, but Spen King remembered having to tell him that they were also impractical. As this was a Land Rover, it would have to be constructed in such a way that its body elements could be shipped abroad for overseas assembly in what was essentially ‘flat-pack’ form. So Bache decided that the best thing to do was to tidy up the existing King–Bashford design. In practice, he put the head of his Land Rover team, Tony Poole, on to the job while retaining oversight of the project and providing guidance.

David Bache proposed a very distinctive, almost streamlined shape, and built this scale model to demonstrate it.

This later scale model has a version of the ‘streamlined’ shape on the far side, but on this side shows a much simplified design that anticipates the one chosen for production.

The first quarter-scale model of the ‘tidied’ design was done in July 1967, and by September all parties were agreed that this was the way to go. So Bache had a full-size clay model built, which was ready that month. Thinking that the model would look better with some sort of badges, Tony Poole hunted around the studio for some letters, and found enough to make the name ‘Road-Rover’, which he put on the bonnet.

At this stage, the new Land Rover still had no proper name apart from ‘100-inch Station Wagon’; Road-Rover had been the name of an aborted project from the 1950s that had combined a simple Land Rover-like station wagon body with a Rover saloon car chassis. Its aims had been broadly similar to those of the 100-inch Station Wagon, although there was absolutely no direct connection between the two projects – and Spen King was most insistent on this point. Nevertheless, photographs of the model with its Road-Rover badging have caused endless confusion over the years, and the Road-Rover name even found its way on to a May 1968 engineering drawing! Tony Poole would later make amends by coming up with the name of Range Rover – but that was still some way in the future.

The full-size clay was pictured in the Styling Studio in September 1967. There are 15in wheels, wearing Rover 2000 hubcaps, and Tony Poole has added that infamous Road-Rover lettering. Pictures from this session were used in Geof Miller’s product brochure a few months later, with the name Snopaked out!

Although David Bache’s final styling proposal was very recognizably derived from the King–Bache–Crompton design, it also demonstrated his considerable design skill. At the front he provided a strong visual identity with a bold black grille, large rectangular sidelight-and-indicator lamp clusters, and a rugged-looking bumper. He gave greater definition to the bonnet shape by adding castellations at the leading edges – and that also suited the production engineers because it gave additional strength to the bonnet panel. Those castellations have appeared on every new generation of Range Rover since, and are universally regarded as part of the Range Rover DNA.

Bache’s restyle also gave more character to the sides and rear of the vehicle. Where the King–Bashford prototype appeared ‘clinker-built’, like a boat, Bache took the horizontal swage lines and turned them into a side indentation feature. He matched the chunky front lights by large wraparound lamp clusters at the rear, added another rugged-looking bumper, and brought the side indentation feature round to give more character to the lower tailgate. The result was an imposing-looking vehicle with a much more attractive appearance than any existing four-wheel-drive estate, and yet one that also reflected the ruggedness that was an essential part of its character.

Seat design proved problematical, and this rather intricate design was among the proposals. It was probably intended to be for the de luxe version.

King and Bashford had not even attempted to style the interior of their first prototype – they had simply had some very basic Land Rover-style seats made up to get the vehicle into running condition. When Technical Director Peter Wilks first drove it (the morning after that unofficial test outing to MIRA), there was only one seat, and when Spen King came along for a ride, he had to sit on a wooden box. So the Styling Department had a completely free hand in this area. Bache entrusted this part of the job to a team working for Tony Poole, and work began in the spring of 1968.

At this stage, the thinking was that there would be two levels of trim: a standard level for the proposed 4-cylinder model, and a de luxe level for the V8. As a first step, the stylists created a sculpted facia shape that would be simple to manufacture and was easily adaptable for both left- and right-hand drive. They then moved on to the door trims, which rapidly took on their definitive shape. However, the seats created some complicated problems, because their design broke new ground.

Safety was a major consideration for the 100-inch Station Wagon because Rover hoped to sell it in the increasingly safety-conscious US market. As a result, the new model would need front-seat safety belts at the very least. However, putting the upper mountings on the B-post would have left the belts – all static types in the 1960s – trailing in the way of rear-seat passengers trying to get in or out, while mounting the belts to the floor so that they ran up and over the seat backs would have caused difficulties when the seat backs were tipped forwards.

So Rover decided to mount the belts to the seats themselves, and to mount the seat bases very firmly to the floor. The stylists worked with the company’s safety engineers to reach a solution that would also allow the seats to slide back and forth and to tip forwards, and the seats they developed were then unique in the automotive world. Rover had to seek special approval for this innovative design from the legislative authorities in many of the territories where they planned to sell their new model.

DEVELOPMENT ON A SHOESTRING

All the developmental work on the 100-inch Station Wagon during 1968 was done on the first two prototypes, which were not representative of the intended body styling, while only 100/2 had the intended suspension and braking design. This was typical of the way Rover worked at the time,because it was a small company and had to keep a very tight control on costs – but such a way of working is almost inconceivable to modern car engineers.

Even though the body shape was fairly well established by the end of 1967, the design had to be reviewed by Rover’s production engineers, who required a few changes. So the overall body design was not signed off until January 1968, which was too late in the schedule for the second prototype to have it. As a result, the first prototype to have the production body design was 100/3, on which work did not begin until early 1969.

In the meantime, Spen King had gone. The amalgamation of Leyland (Rover’s owners since 1967) with British Motor Holdings early in 1968 resulted in some senior management changes. King remembered that he was summoned before Sir Donald Stokes, Chairman of what was now the British Leyland Motor Corporation, and was told he was being promoted and given overall responsibility for engineering at Triumph. ‘I was flabbergasted,’ he recalled later, ‘but I wasn’t given any choice in the matter.’

So from June 1968, Gordon Bashford took charge of New Vehicle Projects, and with it he assumed residual responsibility for the design of the 100-inch Station Wagon. In practice, however, the main design phase was over, and so further work was almost entirely down to the development team under Geof Miller, who reported directly to Technical Director Peter Wilks.

Two more important events took place in late 1968. During November, Geof Miller issued a technical brochure to all departments involved in the project, in which he resumed the specification of the 100-inch Station Wagon. By this stage it was clear that the V8 engine would be used in all the first vehicles, and that the planned 4-cylinder model would follow later – no work had actually been done on this lower-powered variant. However, the automatic gearbox was no longer under consideration, and all vehicles were to have the four-speed manual type.

The second important event was that the 100-inch Station Wagon acquired a name. The hunt for one seems to have begun in November, and it was probably then that stylist Tony Poole put forward his idea. ‘We were playing with names like Land Rover Ranger,’ he remembered, ‘and I said, why not call it a Range Rover? Everybody seemed to think that this was a good idea!’

It certainly was a good idea. Not only did it incorporate the Rover name, but the use of the word ‘range’ immediately suggested long distances and wide open spaces, opening up the image in a way that the Land Rover name simply did not. It might not be fanciful to suggest that this name played an important part in the new model’s success, because not only did it roll off the tongue easily, it also suggested the aspirational qualities that the Range Rover would soon come to embody in the public imagination. The only drawback was that the link with Land Rover was lost, and so early production models carried an oval badge on the tailgate that read ‘by Land Rover’. Even so, the Range Rover soon acquired a distinct identity of its own – and there are still some people today, nearly fifty years after the event, who do not realize that Range Rovers are a Land Rover product!

The Range Rover name was formally adopted at a meeting on 18 December when the project team met representatives of the Rover Sales Department to discuss a number of issues. At this same meeting, the plan for a 4-cylinder model was scrapped (much to the relief of Peter Wilks, whose engineering department was already overstretched) when Sales said they did not think it would help them sell any extra vehicles. Sales also went on record as saying that the Range Rover’s two-door configuration was ‘a tragedy’, and that they were convinced there would be customer pressure for a four-door model.

In that, they were right; in their belief that the Range Rover would have snob appeal they were also right; in their estimates of annual sales between 12,500 and 13,500 they were almost right; but their prediction of an eight-year production run for the new model was to prove a serious underestimate.

A RUSH JOB

The full prototypes were too valuable to smash into a concrete block during 1968, so this hybrid chassis – half Range Rover and half Land Rover – was built for the first crash test.

The development team pressed on with its prototype programme, aiming towards a launch date for the Range Rover of late 1970. An early priority was to crash-test the chassis to see how it behaved, but during 1968 there were still only two prototypes, and both were still needed for development work. So a special simulator was built, using the front end of a Range Rover chassis with the V8 engine installed, attached to the back half of a Land Rover chassis. This was rammed into a concrete block at MIRA in November 1968, and the results were encouraging.

The production body design finally appeared on 100/3. These were the only two prototype Rostyle wheels available – there were plain disc-type Land Rover wheels on the other side.

The third Range Rover prototype was completed in April 1969. Number 100/3 was the first with production body styling, although the interior design had not been completed and so it was fitted with some modified Land Rover seats as a temporary expedient.

Left-hand-drive prototype 100/5 was used for badging trials in autumn 1969 before going out for hot-weather testing in Africa.

The fourth and fifth prototypes, number 100/4 with right-hand drive and number 100/5 with left-hand drive, followed in August 1969. Both went straight into the development programme. Prototype 100/6 with right-hand drive followed soon afterwards, and along with 100/5 it went on a hot-weather proving expedition in the Sahara desert in November. This trip lasted a month and was planned to include a recce of areas in the Atlas Mountains in Morocco that could be used for the Range Rover press and dealer launch that was expected to be held at the end of 1970.

However, a lot changed while Geof Miller and Roger Crathorne were away in North Africa. While they were still there they heard from Solihull that top management was now asking if the Range Rover could be ready for production in the first half of 1970, ideally so that it could be launched at the Geneva Motor Show in March. Realistically, the answer was a firm ‘No’, but there was not much point in saying so. The request was actually an instruction that had come down from the top of British Leyland, where Chairman Sir Donald Stokes had promised to demonstrate the dynamism of British Leyland by introducing at least two significant new models every year. The two he had chosen were two that had impressed him when they had been presented to him earlier in the year, the Triumph Stag grand tourer (which had become Spen King’s responsibility) and the Range Rover.

Geof Miller successfully argued that a launch at Geneva in March was out of the question, but he had to concede that a launch over the summer might be feasible. The planned Morocco introduction was immediately cancelled and was re-scheduled for June 1970, with the press event being held in Cornwall and the dealer launch at the factory in Solihull. So the next stage was a radical speeding up of the final development stages. There were still dozens of issues to be sorted out. Some questions – such as what modifications might be needed to make the new model saleable in the US market – had not even been seriously addressed. So Geof Miller agreed with Peter Wilks to ‘concentrate on problems likely to leave owners stranded at the roadside, and treat “annoyance” problems as second priority.’ A number of ideas for the vehicle’s future development were simply put on the back burner.

A rearward-facing additional seat was also under development, but was not carried forwards to production.

The new schedule impacted on some elements of design as well as on development. The Styling Department was working on the planned de luxe interior, but was now instructed to come up with a production-ready design that could be made at relatively low cost – and quickly. So they stopped work on the de luxe seats, and also the planned optional rearward-facing bench that was designed to fold down into a bed – and would have allowed the Range Rover to have been sold as a camper, with some reduction in Purchase Tax. As Tony Poole remembered, ‘it was all hands on deck to get the interior ready in time! So we never did get to do our luxury interior, and the original Range Rover was always a lot more spartan than it was ever intended to be.’

Fortunately, the intention had always been to install the Range Rover production lines towards the end of 1969 in order to build the pilot-production batch and the dealer launch stock well in advance of a start to sales. Those lines, built in the South Block behind the main administrative offices at Solihull, were pressed into service almost as soon as they were completed. Build of the first three pilot-production vehicles began in December 1969, before the seventh prototype (100/7, with left-hand drive) had even been completed. A planned eighth prototype was cancelled as redundant, and the development team used pre-production vehicles from the assembly lines for their final work.

Better late than never! The MIRA crash test was actually carried out after the Range Rover had been launched. This was 100/5 after its terminal encounter with a concrete block.

So the first half of 1970 became an intensely busy period. The Range Rover project team was formally transferred from New Vehicle Projects into mainstream Land Rover Engineering, and was further supplemented by John Orgill as Assistant Project Engineer and by Technical Assistants Rod Gill, Malcolm Ainsley and Vyrnwy Evans to cope with all the extra work that had to be done in time for the launch that summer. And still some jobs were not completed in time: the crash test at MIRA (less important in those days than it has since become) was not carried out on prototype 100/5 until August 1970 – by which time the Range Rover was already in volume production!

THE PRE-PRODUCTION (‘YVB’) BATCH

The pre-production Range Rovers were built in the first half of 1970, while the development team was still completing its work. In addition to the three whose build had started in December 1969, there were twenty-five further chassis. All except one were given chassis numbers in the production sequences; the one exception was built as a driveable demonstration chassis, and never had a body or a chassis number (although it did have an Engineering Fleet number). This and two other examples were built with left-hand drive.

Rover needed to use some of these vehicles on the road, but wanted to conceal their identity from the public in order to maximize the impact of the planned launch in summer. So the company obtained a batch of registration numbers from the Surrey licensing authority; the XC sequence issued in Solihull was all too recognizable, and would immediately have led onlookers to the conclusion that they were seeing a new Rover product. The Surrey numbers ran from YVB 150H to YVB 177H. YVB 150H was given to prototype 100/7, and YVB 176H was never allocated; the vehicle that would have had it was used as the development team’s ‘hack’ for a time until it was brought up to production standard and sold to a Rover employee in June 1971, when it became UXC 159J.

The production seats were not ready in time for the build of the pre-production vehicles. This view inside one of the two left-handdrive examples shows the black seats that were installed on a temporary basis: they were simply modified Land Rover seats.

The first three pre-production vehicles were registered in January 1970; there were seven more in February, thirteen in March, and one each in May and July. A few of them were further disguised with Velar badges, and most were actually registered as Velars (see sidebar). Although all of them were built to the production specification as it stood at the time, that specification was still evolving, and they therefore had a number of differences from the eventual volume-production vehicles. Land Rover dealer Brian Bashall (who founded the famous Dunsfold Collection) saw the pre-production Range Rovers being built, and remembered that the assembly-line staff had to work some things out as they went along – such as where to drill a hole in the bulkhead so that the choke cable could pass through it!

Manufacturing problems in this period also caused the aluminium alloy bonnet to be changed for a steel one after several vehicles had been built: the alloy would not ‘draw’ very well into the castellation features at the panel’s leading corners, and the aluminium bonnets tended to split in this area. The facia panel was changed, too. The first batch of thirty had been run off with a smooth finish in order to minimize tooling costs, but once Rover were satisfied with the panel fit, the tools were modified to give a grained finish. One problem was that the passenger side of the facia tended to droop, and so a reinforcing bracket had to be added. Then production was simplified by using silver-finish wheels with all six body colours; the original plan had been to specify wheels enamelled in Sahara Dust with Lincoln Green, Masai Red and Sahara Dust itself.

The pre-production batch were registered in the YVB-H series. This one, later owned by Geof Miller, shows the later type of Velar badge, which used Rover saloon letters mounted on a black plate that was secured to the holes in the bonnet for the real badges.

THE PRESS LAUNCH (‘NXC’) BATCH

The press-launch Range Rovers had NXC-H numbers. Here, Geof Miller demonstrates the superb handling of NXC 235H off-road at the Cornwall press launch.

Most of these changes had gone through by March or April, when the first of twenty Range Rovers planned for use on the press launch in June were built. They came off the assembly lines in April and May that year, and were close enough to the final production specification to represent the new Range Rover to the world’s media. However, they still had a number of detail differences from the volume-production models that followed. All of them had production chassis numbers, and were registered together on 27 May 1970 in the sequence NXC 231H to NXC 250H. Once this batch had been completed, the assembly lines started turning out Range Rovers in gradually increasing numbers for the start of showroom sales on 1 September.

THE VELAR NAME

In the mid-1960s, Rover had registered a Velar company to give them a ‘deniable’ trading name for use on prototype vehicles. The name came from Mike Dunn, chief engineer at Rover-owned Alvis, who was asked to create a name containing the letters from ALVIS and ROVER. Geof Miller adds that ‘some knowledge of the Spanish and Italian languages, and the subterfuge that went with building and testing a secret prototype, led Mike to the word VELAR. In Spanish, VELAR means “to look over, to watch over, to keep vigil”, while in Italian VELARE means “to veil, to cover”.’

Geof Miller made up just one of these badges, which was used to disguise 100/1 when it went out on the roads.

The Range Rover team used the name to conceal the identity of their first prototypes and the pre-production vehicles, and Geof Miller had some badges made. There were three types of these. The first one deliberately looked like a hybrid of Volvo, Nissan and London Underground logos, and used Rover P6 saloon lettering, with the V inverted to form a barless A. The L was a cut-down E. Just one of these badges was made, and it was only fitted to the front of the first prototype, 100/1.

The second type was used on prototypes 100/2 to 100/6 at some point in their lives, and again used Rover P6 bootlid letters, this time mounted directly to the bonnet. The third type was used on the YVB-registered pre-production Range Rovers where necessary, and this had the later, larger P6 bootlid letters (introduced in autumn 1969) on a satin black aluminium plate. In this case, the inverted V was made into a proper A by the addition of a bar.

As far as is known, none of the NXC press Range Rovers ever carried a Velar badge. However, nearly half a century later, in 2017, the Velar name resurfaced. Land Rover decided that it had just the right qualities for their new fourth model in the Range Rover line-up, fitting in between the Range Rover Evoque and the Range Rover Sport.

CHAPTER TWO

ON THE SURFACE, 1970 –79

The Range Rover was launched in summer 1970 to what amounted to a standing ovation. Press and public alike immediately saw the attraction of this new model, which was quite unlike anything else available at the time. Even though US makers had been building four-wheel-drive leisure vehicles for some years, none of those then available had anything like the dynamic qualities of the Range Rover, much less its style.

So sales took off with a rush, and before long it became clear that Solihull could sell all the Range Rovers it could build, and more. A black market arose quite early on, where brand-new Range Rovers changed hands for considerably more than their showroom price.

Meanwhile, Solihull was following its predetermined plan of launching the new model into overseas markets, and by the spring of 1971 it was on sale in several European countries. Switzerland, with its high concentration of wealthy potential owners and its tricky winter conditions, was one of the first to get it. Austria and Germany followed, but countries such as France and Italy were not high on the priorities list because of their high taxation on vehicles with large engines such as the V8 in the Range Rover.

A special white-painted cutaway show chassis displayed the Range Rover’s underpinnings to the public. The stand was clearly branded Rover, although the company was part of British Leyland by this time.

While the Range Rover was finding its place in the market, important changes were afoot within British Leyland. Since the group’s formation in 1968, Rover had been largely left to manage itself, although there had been occasional edicts from the BL Board, such as when Lord Stokes had called for the Range Rover launch to be brought forward. More worryingly for Rover, BL cancelled their planned new P8 saloon when it was a few months away from production in early 1971, on the grounds that it would clash with the company’s Jaguars.

The Range Rover was rolled out to continental European markets during 1971. This early model for Austria was fitted with the under-bumper auxiliary driving lamps that were optional at the time.

By spring 1971, a potential clash with Triumph was averted when the two marques were instructed to pool resources on another new saloon, which later became the Rover SD1. Then in early 1972, Rover and Triumph were merged into a single business unit called (unsurprisingly) Rover-Triumph. This in turn was part of British Leyland’s new Specialist Division, which gave its initials to that new Rover saloon.

These changes were part of a broad reorganization that British Leyland undertook at the start of the 1970s. Land Rover remained attached to Rover as a part of Rover-Triumph, although rather uncomfortably so. But the main difference was that Rover was no longer in full control of its own budget, even though its last Chairman, A. B. Smith, now had the title of Divisional Chairman and sat on the British Leyland Board.

So although the Range Rover was earning good profits, these now went into a corporate pot from which British Leyland would allocate funds to its various divisions as it saw fit. The biggest money-pit was the loss-making Austin-Morris car division, and it soon became apparent that there was not enough spare cash for serious investment in developing the Range Rover further.

Before the money ran out, Solihull had embarked on a programme of developing the Range Rover along the lines it had developed the Land Rover. So the early 1970s saw the introduction of special extended-chassis ambulance and three-axle airfield fire tender derivatives. Sadly, in treating the Range Rover as if it were just another Land Rover, Solihull had missed the potential in its own creation. The customers could see it, and so could a number of aftermarket specialists, who quickly exploited the gaps that remained while the Range Rover struggled with minimal development funding. Four-door conversions, more powerful engines, better braking systems and a whole host of luxury features became available through the aftermarket to those who had the wealth to pay for them.

The Land Rover engineers could do little except stand by and watch as the initiative on Range Rover development passed to these aftermarket specialists. It would not be until 1978, when Land Rover Ltd was created as a standalone business unit within British Leyland, that there was any chance of change. The company’s newly appointed Managing Director, Mike Hodgkinson, was determined to fight the Land Rover corner, and he used the funding that was made available to him to make a new start on Range Rover development.

All these problems meant that the Range Rover appeared to stagnate during the 1970s, as only a small number of changes reached production before the end of the decade. There were not even any changes to the paint options, although there was a limited amount of change to the interior. However, behind the scenes this was an extraordinarily busy time, and the Range Rover story of the 1970s is much more complicated than many people imagine. So for clarity, this book divides it into two chapters. This one looks at the mainstream production models – the story as it appeared on the surface. The chapter that follows looks at what was going on out of the public gaze – how Solihull was trying to develop the mainstream models behind the scenes, and at the special purpose conversions approved by the Special Projects Department.

In this period, Range Rovers were not distinguished in terms of model-year, even though specification changes sometimes did coincide with the start of a new sales season in the autumn. The Rover Company treated them in the same way as it treated its Land Rovers: specification changes were made to counter problems, or when a genuinely useful revision had been designed. So where Rover cars were regularly refreshed to attract new buyers at the start of every model-year, Range Rovers were modified only when it became necessary.

Range Rovers were always noted as excellent towing vehicles, and the RAC bought several for vehicle rescue operations. However, there was clearly a publicity purpose to this picture: note the Loxhams signage on the trailer! Although the rear of the Range Rover sits low, the Boge self-leveller will pump it up when the vehicle begins moving.

When they made major specification changes to the Range Rover, its makers identified these for the benefit of dealer service staff by changing the suffix letter of the chassis number. So this chapter traces the development of the Range Rover during the 1970s with reference to those suffix letters. There is also a ready-reference list of the major changes in the sidebar ‘1970–79: The Key Specification Changes’ at the end of the chapter.

This tailgate badge was used on 1970s models, to reinforce the link with the parent marque.

THE PRESS LAUNCH

The Range Rover press launch was based at the Meudon Hotel, between Falmouth and the River Helford, and was held over a six-day period from Monday 1 June to Saturday 6 June 1970. Stories were embargoed until 17 June.

Journalists who attended stayed for two days, and gained their impressions by driving examples of the twenty specially prepared, NXC-registered Range Rovers. A road route demonstrated the vehicle’s everyday character, while its off-road ability was showcased at the Blue Hills mine, an area of steep and rough ground near St Agnes, which was better known as the site of the Motor Cycling Club’s classic Land’s End trial. To demonstrate the Range Rover’s high-speed capability, there were foot-tothe-floor runs on the runway at RAF St Eval.

SUFFIX A