28,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

The third-generation or L322 Range Rover took the Land Rover marque firmly into the luxury market at the start of the 2000s, and set the tone for the models to follow. This book documents the whole story of this milestone model with the aid of more than 200 photographs. It includes: the story of the model's origins as the L30 project when BMW owned Land Rover; the styling, engineering and specification changes introduced over the lifetime of L322 from 2001 to 2012 and a chapter on the model's career in the USA. There is an overview of the aftermarket enhancements from the leading specialists of the day.tFull technical specifications are given, plus paint colours and interior trim choices and finally there is guidance on buying and owning one of these acclaimed vehicles - the L322 Range Rover.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 302

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

OTHER TITLES IN THE CROWOOD AUTOCLASSICS SERIES

Alfa Romeo 105 Series Spider

Alfa Romeo 916 GTV & Spider

Alfa Romeo 2000 and 2600

Alfa Romeo Spider

Aston Martin DB4, 5, 6

Aston Martin DB7

Aston Martin V8

Austin Healey

BMW E30

BMW M3

BMW M5

BMW Classic Coupes 1965–1989 2000C and CS, E9 and E24

BMW Z3 and Z4

Classic Jaguar XK – The Six-Cylinder Cars

Ferrari 308, 328 & 348

Frogeye Sprite

Ginetta: Road & Track Cars

Jaguar E-Type

Jaguar F-Type

Jaguar Mks 1 & 2, S-Type & 420

Jaguar XJ-S The Complete Story

Jaguar XK8

Jensen V8

Land Rover Defender 90 & 110

Land Rover Freelander

Lotus Elan

Lotus Elise & Exige 1995–2020

MGA

MGB

MGF and TF

Mazda MX-5

Mercedes-Benz Fintail Models

Mercedes-Benz S-Class 1972–2013

Mercedes SL Series

Mercedes-Benz SL & Noakes SLC 107 Series 1971–1989

Mercedes-Benz Sport-Light Coupé

Mercedes-Benz W114 and W115

Mercedes-Benz W123

Mercedes-Benz W124

Mercedes-Benz W126 S-Class 1979–1991

Mercedes-Benz W201 (190)

Mercedes W113

Morgan 4/4: The First 75 Years

Peugeot 205

Porsche 924/928/944/968

Porsche Boxster and Cayman

Porsche Carrera – The Air-Cooled Era 1953–1998

Porsche Air-Cooled Turbos 1974–1996

Porsche Carrera - The Water-Cooled Era 1998–2018

Porsche Water-Cooled Turbos 1979–2019

Range Rover First Generation

Range Rover Second Generation

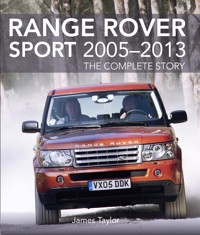

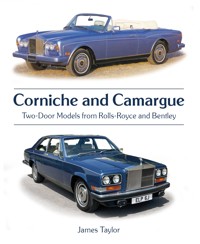

Range Rover Sport 2005–2013

Reliant Three-Wheelers

Riley Legendary RMs

Rover 75 and MG ZT

Rover 800 Series

Rover P5 & P5B

Rover P6: 2000, 2200, 3500

Rover SDI – The Full Story 1976–1986

Saab 99 and 900

Subaru Impreza WRX & WRX ST1

Toyota MR2

Triumph Spitfire and GT6

Triumph TR7

Volkswagen Golf GTI

Volvo 1800

Volvo Amazon

First published in 2022 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2022

© James Taylor 2022

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 71984 008 1

Cover design by Maggie Mellett

CONTENTS

Introduction and Acknowledgements

Timeline

1 CREATING A NEW RANGE ROVER

2 THE FIRST PHASE: 2002–5 MODELS

3 REDEVELOPMENT

4 BOOM AND BUST: 2006–9

5 A BLAZE OF GLORY: 2010–12

6 ACROSS THE ATLANTIC

7 EMERGENCY SERVICES AND THE MILITARY

8 BUILDING THE L322

9 GOING BEYOND: THE L322 AFTERMARKET

10 PURCHASE AND OWNERSHIP

Appendix I: Identification

Appendix II: Production Figures

Appendix III: How Much Did It Cost?

Index

INTRODUCTION AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The third-generation, or L322 Range Rover, was in production during a pivotal period in the history of Land Rover. It was a period when the company moved its products firmly into the luxury sector, while retaining the very high levels of off-road ability that the Land Rover marque traditionally provided. It was also a period that encompassed no fewer than three changes of company ownership. When L322 was conceived, Land Rover was owned by BMW; before it went on sale, the company had been sold to Ford; and midway through its production life the company was again sold, this time to Tata.

Yet there was a remarkable coherence about the story of the L322 itself, with the model getting better and better as time went on. Throughout its production life, there was never any doubt that this Range Rover was a staggeringly competent blend of prestigious luxury transport and multipurpose off-road vehicle. That the cost of ownership was high should come as no surprise.

As the Editor of Land Rover Enthusiast magazine for most of the time when L322 was in production, I was in a privileged position to follow the model’s career and I did so with interest and enthusiasm. Throughout that period (and since), many people at Land Rover and in other companies that worked with the L322 have willingly helped me to understand not only what was happening with the model, but also why it was happening, and a great deal of what they told me has gone into this book.

There is never enough room in a book like this to thank everyone who has provided information or pictures, so I will take the easy way out and simply say thank you very much – you know who you are. And, because history is never finite, I will add that anybody who can add more information (or correct what is here) is very welcome to contact me through The Crowood Press.

James TaylorOxfordshireApril 2021

PICTURE CREDITS

Andrew Fenton

Arden Automobilbau GmbH

Hamann Motorsport

Jérôme André

Land Rover (JLR)

Liberty Electric Cars Ltd

navigator84 via Flickr and Wikimedia Commons

Nick Dimbleby

Overfinch

Patrick Sutcliffe

Project Kahn

PVEC

Range 7

Revere London

Richard Stickland

Shaun Henderson (via Peter Hall)

Spirito di Vino magazine

Stefan Thiele

The Chauffeur magazine

Totally Dynamic

Vantagefield Ltd

TIMELINE

1996 (September)

Start of formal development programme, under code name L30

2000 (summer)

Land Rover sold to Ford; L30 programme renamed L322

2001 (September)

First media release; Td6 diesel and V8 petrol engine options with five-speed gearboxes

2002 (February)

First customer deliveries

2002 (June)

First L322 sales in USA

2002 (September)

Autobiography bespoke finishing scheme available in UK

2003 (September)

First Westminster Edition in USA

2003 (November)

First Autobiography EditionFirst European special edition (in France)

2004 (August)

2005 models introduced with larger dashboard screen

2005 (January)

Second UK Autobiography Edition 2006 models previewed at Detroit Motor Show

2005 (June)

Sales begin of Range Rover Sport (L320)

2005 (spring)

First 2006 models on sale; new Jaguar petrol engines including supercharged type, with six-speed gearboxes

2005 (September)

Thirty-fifth Anniversary Edition

2006 (September)

2007 models introduced; Terrain Response added and 3.6-litre TDV8 engine in place of Td6

2007 (summer)

Forty-strong Twentieth Anniversary Edition for USA

2007 (autumn)

Naturally aspirated petrol V8 withdrawn from European markets

2008 (March)

Land Rover sold to Tata and becomes part of Jaguar Land Rover (JLR)

2008 (summer)

Autobiography package option introduced to USA

2009 (March)

Westminster Edition for Europe

2009 (June)

2010 models introduced, with new 5.0-litre V8 and supercharged engines, plus a major facelift

2010 (September)

TDV8 engine enlarged to 4.4 litres

2010 (November)

An L322 becomes the commemorative Millionth Range Rover

2011 (February)

Autobiography Ultimate Edition becomes the most expensive Range Rover yet

2012 (July)

Last L322 Range Rover built

1

CREATING A NEW RANGE ROVER

When the third-generation Range Rover, or L322, model was announced in 2001, all the publicity focus was on its exciting new features. Ford, who had bought the Land Rover business in summer 2000, was understandably keen not to dwell on the fact that it had had almost no involvement in the model’s creation and it was only in later years that the real story gradually became apparent. In fact, what Ford called L322 had started life back in 1996 as a project called L30 when BMW had owned the Land Rover marque, and Ford had taken it over from the German company as a turnkey project.

Dr Wolfgang Reitzle was head of R&D at BMW and oversaw the initial integration of the Rover Group with the German company. He was the driving force behind the new Range Rover.

Within those five years between 1996 and 2001 lies a fascinating history that is still not widely understood today. In fact, the story of the third-generation Range Rover can be traced back even further – to January 1994 and BMW’s purchase of the Rover Group from British Aerospace. At that stage, the German company appointed its highly respected R&D chief, Dr Wolfgang Reitzle, to oversee the early stages of the integration between the two car makers.

Reitzle was keen to get to grips as quickly as possible with the company’s products, especially those that were in the pipeline for the future. He was a great admirer of the original Range Rover and owned one himself, which he used regularly to take him from his home in Munich to the ski resort of Kitzbühel in the Austrian Tyrol. He considered it the only vehicle available that fulfilled all his needs and it was this passion for the Range Rover that had been behind his initiation of BMW’s E53 project – the vehicle that would be launched in 1999 as the X5.

Reitzle was a great enthusiast of the first-generation Range Rover, but he was much less enthusiastic about its planned replacement, which had been signed off for production and was to be introduced in autumn 1994. According to End of the Road: BMW and Rover – A Brand Too Far by Chris Brady and Andrew Lorenz, ‘on his first visit to Land Rover after the BMW acquisition, Reitzle […] climbed into the new vehicle, donned an aircraft eye mask and spent five minutes touching every inch of the cabin. He then got out and wrote a list of seventy features that he believed should be changed.’

David Sneath was appointed Chief Engineer for the 1999-model Range Rover, but when that was cancelled he was moved to the new L30 project.

The new Range Rover was then so close to production that it was too late to make major changes, but of course Land Rover had already begun to make tentative plans for its midlife update, which was scheduled for autumn 1998 and the 1999 model year. David Sneath had been appointed as Chief Engineer to oversee the update programme, but he had barely settled into the job when there was a major change of plan. Clearly anxious to improve a model he saw as unsatisfactory, Reitzle decided that the 1999 model-year variants needed a more radical overhaul. So Sneath and team found themselves putting together a revised 1999 model-year package that better matched Reitzle’s vision.

Central to the revised plan were new engines. The long-serving Land Rover petrol V8 was close to the limit of its development potential and would be replaced by a far more modern BMW design. BMW’s diesel engines were already acknowledged to be the best of their kind – in fact, Land Rover had already agreed to buy in its 2.5-litre turbocharged diesel for the new Range Rover – and the German company could supply a further improved version. So the revised plan for the 1999 model-year facelift incorporated a 3.0-litre update of the existing 2.5-litre diesel, plus 3.5-litre and 4.4-litre versions of BMW’s latest M62 petrol V8.

There was a fourth engine, too, and this was part of Reitzle’s plan to extend the Range Rover into a higher price bracket. In the mid-1990s, the most expensive models cost just over £60,000, but Reitzle now envisaged a £100,000 Range Rover. Inevitably, this would have very high levels of luxury and convenience equipment, but central to it would be BMW’s flagship engine – the 5.4-litre M73 V12 that was already in production for the company’s 7 Series saloons and, from 1998, would also go into the new Rolls-Royce Silver Seraph. With 322bhp and 490Nm of torque, it was vastly more powerful than any existing Range Rover engine, the most powerful of which delivered 225bhp and 376Nm.

For most of 1995 and well into 1996, work on the 1999-model Range Rover focused on this strategy. Although the 3.5-litre V8 was dropped early on, 4.4-litre V8s were built into several ‘mule’ test prototypes. Two V12-powered prototypes were also built, probably in Germany, and inevitably the motoring press got wind of them and published ‘scoop’ stories of the planned new V12 Range Rover. What the press did not pick up, however, was the darker side of the story: major engineering changes were going to be needed to give enough clearance around the big V12 engine and the front end of the vehicle would need an extra 153mm (6in) of length ahead of the axle to maintain crash safety.

Over the summer of 1996, a Lifetime Planning exercise reviewed plans for the future of the existing Range Rover, and BMW concluded that the cost of the proposed 1999 model-year changes was excessive. Reitzle also believed that the result was still not going to meet his expectations, so he scrapped the 1999 model-year plans and told the Land Rover engineers that he would spend the money on an all-new Range Rover instead. This would bring a freshness to the model that could not be achieved through the planned facelift and it would put the Range Rover a further step ahead of its rivals. As a result, the 1999 model-year facelift was formally cancelled in September 1996; Land Rover was instructed to upgrade the existing model as best it could on a limited budget; and BMW began to focus on the all-new Range Rover.

UNDER CONTROL

Characteristically, Reitzle already had his own ideas: he wanted to build the new Range Rover on the platform that BMW had already developed for its E53 project. So Land Rover scrambled a team of four people to Munich to look at the feasibility of doing this. David Sneath was sent as the engineer, Don Wyatt as the designer (the job that was once known as stylist), Alastair Patrick was the manufacturing representative, and Paul Ferraiolo was the marketing man.

Don Wyatt oversaw L30 from start to finish in the Design Studio.

At this stage, the E53 project had been mothballed; after buying Land Rover, BMW was in two minds about the need to have a Sports Utility Vehicle (SUV) type of product in its range. Some of the early prototypes were brought out for the Land Rover team to look at, including one that did have real off-road ability, but it soon became apparent that the E53 platform was simply not up to the job. Sneath discovered that the driveshafts, differentials and aluminium suspension arms were nowhere near strong enough for the punishment a Range Rover would be expected to take off-road.

There was a certain amount of scepticism at BMW about this result, so as a next stage the four Land Rover people had to prove their point by writing a very detailed paper about what was necessary in a Range Rover. ‘It was the whole DNA of the vehicle,’ David Sneath remembered later, ‘the customer expectations as well as the engineering.’

Once BMW had seen this, the Land Rover team was asked to prepare a full Programme Investigation paper. There was some BMW input into this and the Land Rover team found themselves having to justify all kinds of assumptions that they had always taken for granted. Sometimes, they discovered that their assumptions did not hold up; sometimes, BMW had to give ground. In the end, the paper was approved. Land Rover had made its case for a standalone Range Rover project.

Nevertheless, BMW still intended to keep tight control over development of the new Range Rover. It had agreed that the earliest stages should take place in Germany, because the Rover Group’s engineering headquarters at Gaydon in Warwickshire was already working on several other major projects, and the company appointed its own Programme Director for what was christened the L30 project. This was Wolfgang Berger, who had been Reitzle’s right-hand man in the Rover Group and had come to understand the British way of working. The project code was simply part of a new system that BMW set up for its Land Rover subsidiary and is explained in the sidebar opposite.

All four members of the original team that Land Rover had sent out remained involved with L30 and David Sneath found himself having to pick the engineers he wanted from the UK. There were eventually eighty British staff on the team, each one shadowed by a German opposite number. In the end, there were 300 people working on project L30. Their project office was set up in a disused BMW power-train building in Munich; some British members of the team chose to move to Germany, while others, like Sneath himself, commuted home to the UK at weekends.

One of the earliest tasks that Sneath identified was that of educating the BMW engineers in what Land Rover was all about. Off-road driving is illegal in Germany, ‘and they just didn’t have the experience of it’, he explained later. So he found a forested estate on the Czech border and rented it for a three-week period. BMW engineers were invited along for a series of off-road demonstrations with existing Land Rover products to show just what a Land Rover – and by extension a Range Rover – was expected to do, and why BMW’s own E53 platform would not fit the bill. ‘Then they understood!’ he recalled with a smile.

It must have been at about this time that BMW shipped an E53 prototype across to the UK with the intention of putting it through some off-road testing at Land Rover’s Eastnor Castle test ground. Demonstrations Manager Roger Crathorne was allocated to help out and he remembers the E53 arriving in a covered truck. With it was the E53 project leader, Gerhard Boeschel, and Crathorne decided to take him round the test sites first in one of Solihull’s products. When they had finished, Boeschel turned to Crathorne and said that he was not even going to bother to get the E53 out of the truck, because it was not engineered to do the kind of thing he had just seen!

Nevertheless, the Land Rover engineers who worked on L30 were unanimous in their praise of the skill and determination of the BMW engineers. Once they had understood what was required in a Range Rover, they got on with the job and came up with some top-class solutions that were better than those the Land Rover people had proposed. Inevitably, there were difficulties on the project from time to time. Even though the project language was English and the Land Rover engineers did their best to learn German as well, there were cultural differences in the working environment that had to be overcome. Many of the Land Rover team were not best impressed to hear that BMW wanted to build the new Range Rover at its new US plant in Spartanburg, North Carolina, and Alastair Patrick spent a lot of time shuttling back and forth to discuss the feasibility of this scheme.

LAND ROVER PROJECT CODES UNDER BMW

At the time of the BMW takeover, Land Rover tended to use names rather than numbers as project codes. The original Discovery, for example, had been developed as Project Jay and its second generation was being planned as Project Tempest.

BMW relied on number codes, with an E prefix for complete vehicles (it stood for Entwurf, or project) and an M code for engines (the letter stood for Motor). Beginning in 1994, it brought all the Rover Group project codes into line with its own. Rover Cars projects were preceded by an R and Land Rover projects were preceded by an L (for an obvious reason!). Project Tempest became L25; Project Heartland, for a new mid-range vehicle that did not materialize, became L35; and the new Range Rover became L30.

SPECIFICATION

There was little argument about the hardware that would be in the L30 specification. The new model would have the BMW engines that had been planned for the 1999-model facelift: the 3.0-litre turbocharged diesel; the 4.4-litre petrol V8; and the 5.4-litre V12. All of these would drive through automatic gearboxes; manual gearboxes had not been popular on the second-generation Range Rover and the top models were already only available as automatics. Maintaining effortless off-road capability was essential, as this was a Unique Selling Point for the Range Rover in the luxury car market, so there would be a two-speed transfer gearbox and this would have servo-assisted controls to aid the feeling of luxury and effortlessness.

Yet L30 was drawn up with a different balance of characteristics from the two previous Range Rovers. They had been primarily off-road vehicles, which had been extensively refined to turn them into credible luxury car competitors. In the meantime, luxury car design had not remained static and the latest BMW 7 Series, Mercedes S Class and Lexus LS saloons were remarkably refined vehicles. If L30 was to compete for sales with these cars, its design had to be approached differently. Instead of being a 4×4 that was also a luxury car, it had to be a luxury car that was also a 4×4 – and yet it could not lose any of the traditional Land Rover ruggedness or off-road capability in the process.

The L30 could not have a separate body and chassis like its predecessors. It needed the refinement that could only be delivered by a monocoque body. Land Rover had considered a monocoque design in the early days of the second-generation Range Rover, but did not then have the engineering expertise to deliver one as big as would be needed. However, since those days, two things had happened. First, the company had learnt a great deal about monocoques for off-road vehicles during the design of the Freelander (which was announced at the end of 1997) and, second, Land Rover could call on BMW’s experience with large monocoque structures – although even the Germans had never designed one quite this large before.

It certainly was big. L30 was drawn up with a wheelbase of 2,880mm (113.4in), which was 135mm (5.3in) longer than the wheelbase of the second-generation Range Rover. It also ended up standing 45mm (1.8in) taller. Overall length went up by 237mm (9.3in) and body width by 67mm (2.6in). Land Rover insisted that this extra size was not simply to pander to the US market, where giant SUVs like the Cadillac Escalade and Lincoln Navigator were appearing – although there can be no doubt that the introduction of such large vehicles made the Range Rover’s new size both more necessary and more readily acceptable. The official Land Rover line was that L30’s size was dictated by the plan that it should be able to accommodate occupants of all sizes, up to and including a ‘100th percentile’ male – the typical US basketball player – and still feel spacious.

The structural strength of this monocoque was of course a prime consideration. Not only did it have to be strong enough to carry the anticipated load of passengers and luggage on top of all the power-train and interior elements that would be bolted to it; it also had to meet existing and foreseen crash safety regulations, to tow a trailer weighing 3,500kg (7,716lb), and to withstand Land Rover’s hugely demanding off-road criteria. These included the snatch recovery of a bogged-down vehicle, where a shock loading of up to 5,588kg (5.5tons) might be put into a recovery eye welded to the monocoque.

In the end, the engineers decided to bolt no fewer than three subframes to its underside. One carried the engine and front suspension, one carried the rear suspension, while the third one in the middle carried the gearbox, transfer box and rear engine mount. Extensive use of aluminium in the monocoque reduced the weight gain considerably, although L30 would be heavier than its predecessor when it entered production.

Not only was the monocoque body a major step forward; so was the suspension. Range Rovers already had height-adjustable air suspension and this would be retained. However, all Range Rovers up to this time had depended on beam axles, which were traditional to Land Rovers and gave the best off-road performance. Unfortunately, they also compromised ride comfort and on-road handling to a degree. The Land Rover engineers had been eyeing the possibilities of independent suspension for some time, but had not yet been able to make it work without compromising off-road ability to an unacceptable extent. They now believed that they could make it work without such a compromise.

The critical design breakthrough was achieved by cross-linking suspension units. It was off-road where independent suspension performed poorly, so selecting Low range in the transfer box of L30 also engaged an electronic control system that made the wheels behave as if they were mounted on Land Rover’s traditional beam axles. In other words, as one wheel hit a bump and moved up into the wheel arch, so the opposite wheel moved down to prevent the body making contact with the ground. On the road, when High range was selected, the electronic control system also allowed the vehicle to smooth out the side-to-side movements that could be provoked on some types of rough surface.

The suspension was drawn up with MacPherson struts and double lower wishbones at the front, and with a double-wishbone system at the rear. The differentials, meanwhile, were mounted high up on the subframes under the body and did not hang down below the wheel centre lines as they had on the beam-axled Range Rovers. This meant that L30 would have better underbody clearance than its predecessors and that its air suspension no longer needed the Extended height function of the earlier cars: it did not ground out in the same way and did not therefore need to be lifted off an obstruction.

Range Rovers had always used recirculating-ball steering, because this partially absorbed the shocks encountered in off-road use before they reached the driver through the steering wheel. However, it could also be rather vague in on-road use and that ruled it out for L30, which had to deliver the same crisp and satisfying handling as the latest luxury saloons. So Land Rover chose a ZF rack-and-pinion system with the speed-variable power assistance system that BMW knew as Servotronic. By careful installation, it proved possible to get it to damp out as many off-road shocks as earlier systems had done.

To add to the steering’s sharpness on the road, the front subframe was to be bolted directly to the bodyshell instead of cushioned on rubber bushes. This removed yet another area of imprecision from the steering response. However, BMW did not go for the sporting feel of the BMW X5’s steering, believing it to be an unnecessary requirement.

Further handling precision came from BMW’s insistence on fitting a saddle-type fuel tank. The Land Rover engineers had wanted a minimum fuel capacity of 100ltr (22gal), which meant that a large weight of fuel could move from one side of the vehicle to the other quite quickly under hard cornering and so upset the handling. However, the saddle tank reduced the amount of fuel that would move and also the distance it was likely to move, so minimizing the impact of weight transference on the vehicle’s handling.

There was one more very important element of the core specification and that was the complex electrical architecture that was needed to service those convenience items now expected in a luxury car: an onboard computer; a satellite navigation system; and so on. For this requirement, BMW had a ready answer, by providing elements of the system already in production for its flagship E38 7 Series saloons. This was a sensible move, as Land Rover’s track record with electrically powered luxury and convenience equipment was not a good one. By the time L30 was ready for production, BMW had developed its electrical architecture further and so the entertainment system (radio, navigation, TV and telecommunications) and the automotive computer bus system of the new Range Rover were almost identical to those in the German company’s E39 5 Series saloons.

DESIGN BEGINS

While the Land Rover engineers were working on the hardware with their German counterparts, a completely separate group of people was focusing on the way the vehicle should look. BMW seems to have believed that this was an area where the British company knew best, so when the first meeting of the designers was held in November 1996, there were no German representatives present.

Don Wyatt, who had represented the design side in that four-man team sent to Munich, was put in overall charge of L30’s appearance. He recalls that there was immediate consensus on a number of issues. The Range Rover brand was firmly established and it was largely clear what its customers expected of it. Despite a degree of conservatism, they admired modern technology and design, just as they did in more conventional luxury cars. Wyatt remembered that one of the young designers, Gavin Hartley, set the tone of that November meeting by bringing in a beautifully manufactured yacht pulley. It was carefully engineered, expensively manufactured and functioned beautifully – all characteristics that seemed to define what was needed in the next Range Rover.

Fundamental to the design process at this stage were the precepts of what was called the Land Rover Design Bible, a document drawn up in 1988 by designers George Thomson and Alan Mobberly. The ‘bible’ was not inflexible, but it did identify key exterior characteristics of the Range Rover, such as the clamshell bonnet, chunky grille bars and strong horizontal and vertical lines. Interior design had also been the subject of a major review earlier in 1996 and the recommendations from this included strong vertical and horizontal elements for the dashboard. The L30 interior design team would also draw inspiration from the work of leading British architect Nicholas Grimshaw.

For the first stage of their work after this November 1996 meeting, the Land Rover designers worked out of a contract studio in Coventry rather than from the company’s design and engineering headquarters at Gaydon. Most sketched their ideas on paper, but exterior designers David Woodhouse and Oliver LeGrise both chose to use CAD instead. Normally, there would follow a selection process and the most promising designs would then be turned into 3D models, but Don Wyatt decided instead to ask each designer to select his best design and to turn it into a one-fifth scale hard model by March 1997. As a ‘sanity check’, Wyatt also asked for ideas from an outside agency, choosing Design Research Associates, the company that had been established by the former Rover head of design, Roy Axe, when he had left the company in 1991.

As explained above, the overall size of L30 had already been established and that guided these early thoughts. All the designers focused on the flagship V12 model, because features could be deleted to suit the lesser models more easily than they could be added to a low-specification base design. Their brief called for the new vehicle to ‘look like a Range Rover’, and to most of them that meant it had to look like the first-generation Range Rover, which had only gone out of production a few months earlier. The then-current second-generation model was probably considered off limits for inspiration because Reitzle did not like it; Don Wyatt also felt that it lacked the personality of the original and that this characteristic had to be recaptured for the new model.

Phil Simmons was the designer whose vision for the exterior of L30 eventually won out.

The Phil Simmons proposal was eye-catching from the start with its large air vents and unusual powerboat stance. The wheels have an element of caricature about them, but convey the impression that Simmons wanted.

The key Range Rover elements were present in the sketches that came out of this stage of the design process, but in addition they incorporated body ‘shoulders’, which Wyatt felt added the character that had been missing from the second-generation model’s design. Most striking at this stage was a sketch by Land Rover’s Phil Simmons, which was inspired by the Italian-made Riva power boat – a hugely expensive but elegantly styled millionaires’ plaything. It focused all the character of the vehicle at the front, tapering rearwards and featuring a cabin almost perched at the rear like the superstructure of the boat.

DISAPPOINTMENT AND COMPETITION

On the appointed date in March 1997, the facia bucks and one-fifth-scale exterior design models were brought together in the Design Studio at Gaydon for a progress review by Wolfgang Reitzle. Don Wyatt recalled Reitzle walking into the studio and past all the proposals without saying anything, then coming out with a comment that entered Design Studio legend. He said, ‘They tell me that when I am in the UK, I should think more like an Englishman. So let me simply say, I see nothing here that pleases me.’ With that, he left.

Design Research Associates were asked to provide a one-fifth-scale proposal for the March 1997 selection. It was very different from those put forward from within Land Rover.

The one-fifth-scale model of Phil Simmons’ proposal still retained its powerboat stance and the stand-off bumpers. The rear half-door would only have given access when the front door was also open.

That left Wyatt with the unenviable task of motivating a group of somewhat dispirited designers to move on to the next stage. For the exterior, he arranged an internal voting process that involved the designers themselves, some Rover Cars designers, the Colour and Trim team from the Design Studio, and people from other areas of the L30 project team. The voting, he remembered, closely mirrored the thinking of the design management team. From the interior designers, he selected Gavin Hartley and Alan Sheppard to develop new themes, and he gave Alan Mobberly the difficult task of liaising with the BMW engineers on all aspects of the interior.

The next stage was to turn some of the one-fifth-scale models into full-size clays. Here, modeller Glen Williams works on one of them.

From the early stages of sketched proposals, this one for the interior was by Alan Sheppard.

The schedule called for a final selection of themes to be made later that year and in June a decision was taken about which ones to take to the next stage as full-size models. Meanwhile, Reitzle decided to call for ideas from his own company, commissioning two BMW departments to work up proposals to the full-size model stage. One was the mainstream design studio in Munich, which was then run by Chris Bangle, and their design was known to BMW as the E54. (The absence of that number in the known sequence of BMW designs has often perplexed those interested in the German company.) The second department asked for a proposal was BMW Design Works, the California-based studio that had been set up to keep a close eye on developments in the US market.

The idea was that a final review at Gaydon in August would make a choice from four exterior models, of which two would come from BMW and two from Land Rover. In practice, the Land Rover team stacked the odds in their favour and at the June interim review chose four designs to put forward as full-size models. Designs by Julian Quincy and Phil Simmons were turned into two of them, while a third model showed the Mike Sampson design on the left side and the Paul Hanstock design on the right.

THE CHOICE

At the design review held on 1 August 1997, Reitzle and the members of the Land Rover Board were unable to agree on a final choice. Reitzle favoured the Chris Bangle design from the BMW studios in Munich, but the Land Rover Board did not. Tom Purves, then Land Rover Sales Director and formerly with BMW, pointed out its unfortunate resemblance to a Jeep in the wheel-arch shape. Reitzle, meanwhile, was not at all keen on the Phil Simmons design that had the vote of the Land Rover Board. He did not like the stand-off bumpers that were mounted some distance from the main body (and which Don Wyatt secretly doubted could be manufactured anyway), and he strongly disliked the angular rear end.

The conclusion could be described as a classic British compromise. The designers were to be given more time to refine the two favoured proposals, ready for a final selection meeting in November. Clear instructions were issued to BMW Design and to the Land Rover Design Studio about which features had to be changed in their respective submissions.

This was the full-size clay of the Phil Simmons design, produced for the autumn 1997 design review. The headlights and wheels are two-dimensional only.

This 1997 clay had a design by Mike Sampson on the far side and one by Paul Hanstock on the side nearer the camera. Again, wheels and lights are represented two-dimensionally.