56,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

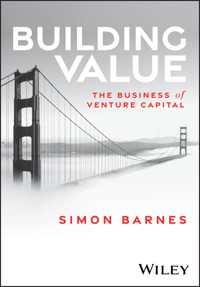

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

Learn the venture capital process and industry from the inside-out

In Building Value: The Business of Venture Capital, renowned professor and venture capital (VC) firm partner Simon Barnes delivers an easy-to-read guide to the often-mysterious world of venture capital and how entrepreneurs and venture capitalists should engage with each other to arrive at constructive start-up investment deals. In the book, you'll discover why successful entrepreneurial finance is more about behaviour than it is about numbers. You'll learn why VC is a people business, first and foremost, and why effectively aligning the interests of funders and entrepreneurs is so important.

You'll also find:

- Insights drawn from the author's 25 years' experience backing and building start-ups in the UK, EU, and US

- A holistic view of the venture capital industry that focuses on building value

- A comprehensive discussion of the entire VC process, from negotiating the deal to helping build a successful venture-backed business

Perfect for students in MBA programs, Building Value is also a can't-miss resource for venture capitalists, entrepreneurs raising capital for the first time, professional fund managers, and professionals and entrepreneurs participating in incubator or accelerator programmes.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 553

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Cover

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright

About the Author

Acknowledgements

Chapter 1 Why Do Start-ups Raise Capital?

Asset Parsimony

The Best Time to Raise Money is When You Don’t Need To

Crossing the Valleys of Death

Is it Just the Money?

Supply and Demand

Summary of Chapter 1

References

Chapter 2 Equity and the Art of Milestone-Based Financing

The Equity Pie

Private Equity and Venture Capital

Fools and Angels

Incubators and Accelerators

Selling Equity is Expensive

Milestones

The Venture Capital Business Model Demands an Exit

The Milestone-based Journey to Exit

The Entrepreneurial Financing Ecosystem

Terminology

Evolution of the Funding Gap

Venture Debt – an Exception?

Dilution Versus Security

What Do We Mean by Building Value?

A Value Creation Stairway or Escalator?

Summary of Chapter 2

References

Chapter 3 A History Lesson

Beginnings

Venture Capital Through History

Summary of Chapter 3

Notes

References

Chapter 4 Business Models

Capital Gain

Agency

Information Asymmetry

Fund Structures

Carried Interest and Loan Repayment Points

Money Plus

How VCs Deploy Their Funds

The Dynamic Allocation of Capital

Raising Successive Venture Capital Funds

Managing Multiple Funds

The Venture Fund Loop

Corporate Venture Capital

Summary of Chapter 4

Chapter 5 A Day in the Life

Opportunity

Supply and Demand

Is a Business Plan Worth It?

Life is a Series of Pitches

Networks, Connections and Reputation

The Selection Process

How to Pick a Winner

Decision Dynamics Within A VC Firm

Signing a Term Sheet

Common Reasons For Rejection

How VCs Compete for Deals

Evaluation Goes Both Ways

Summary of Chapter 5

Chapter 6 Valuation

How Much Equity Do Entrepreneurs Have To Sell?

The Example of UBER

What is an Idea Worth?

Value Versus Valuation

Dividing the Start-Up Equity Pie

Valuation Terminology: Pre- and Post-Money Valuation

The Game of Offer and Acceptance

Valuation Methodologies

The Venture Capital Method

Valuation is a Market-Driven Negotiation

Financing History

Timing

Reputation

Sometimes more is… more

Not all Shares are Created Equal…

Preferred Shares, Preference Shares and Cascades

Alternatives in the Market...

Unpleasant Cousins…

A Hierarchy of Outcomes

Preference Cascades

If an Investor Asks…

The Rule of Thumb…

Summary of Chapter 6

Reference

Chapter 7 Inside the Deal

Term Sheets

Who and When?

Purpose

Core Principles

A Delicate Dance

How to Choose A VC?

Building Investor Syndicates

Only One Term Sheet…

A Guided Tour of a Term Sheet: ABC Ventures

Negotiating with VCs: A Practical Example

Summary of Chapter 7

Chapter 8 Raising the Next Round

Building Value Before Launching the Next Round

Adverse Events and the Valleys of Death

Conducting the Orchestra

What are the Differences?

How to Begin the Process

The Convertible Loan

Raising the Next Round: A Practical Example

Summary of Chapter 8

Notes

Chapter 9 Towards the Exit

Defining The Exit

Why is an Exit Needed?

Taxonomy of Exits

The Initial Public Offering… an Exit?

Exotic Exits

The Drama of the Exit

When?

Forced Sales: Drag Along and Grandstanding

Who Decides: The Role of the Board?

What Do Exits Mean for Founders?

What Do Exits Mean for VCs?

Preference Cascades and the Management Carve-Out

Terrible Exits

The Living Dead

The Exit: A Practical Example

Summary of Chapter 9

Reference

Chapter 10 Building Value: The Business of Venture Capital

Crossing the Valleys of Death

Money Plus and Reputation

Dilution and Control

Milestone-Based Finance

Capital Gain and the Venture Fund Loop

Valuation as Art

Preference Cascades

The Role of the Board

The Drama of the Exit

A Final Word

Case Study Solutions

Nanomachines: Creating Value Through Milestones

Gabriel.AI: Raising the First Round

SolidEx: Raising Capital to Grow

Summary

Syntemix: Engineering the Exit

Summary

Index

End User License Agreement

List of Illustrations

Chapter 1

Figure 1.1 Financing the journey to the Promised Land.

Figure 1.2 There are multiple Valleys of Death.

Figure 1.3 The credibility carousel.

Figure 1.4 The NASDAQ is a good proxy for the state of the venture capital market.

Chapter 2

Figure 2.1 The private equity spectrum.

Figure 2.2 Dividing the equity pie to align interests.

Figure 2.3 The effects of dilution.

Figure 2.4 Baby steps, then strides towards success.

Figure 2.5 The simplest business model in the world?

Figure 2.6 Milestone-based financing is the key to the journey.

Figure 2.7 The financial food chain.

Figure 2.8 Value is not the same as profit.

Figure 2.9 The stairway to value.

Chapter 4

Figure 4.1 The role of VCs in building value.

Figure 4.2 The role of VCs as intermediaries.

Figure 4.3 The flow of funds.

Figure 4.4 Building a milestone-based portfolio.

Figure 4.5 Dynamic allocation of capital across a portfolio.

Figure 4.6 Raising the next fund.

Figure 4.7 Managing overlapping funds.

Figure 4.8 The venture fund loop.

Chapter 5

Figure 5.1 Proactive design of the portfolio.

Chapter 6

Figure 6.1 Dividing the pie.

Figure 6.2 The game of offer and acceptance.

Figure 6.3 When art becomes science.

Figure 6.4 Ordinary shares, preferred shares and preference shares.

Figure 6.5 ABC Ventures versus the management team.

Figure 6.6 A hierarchy of outcomes for the entrepreneurial team.

Chapter 7

Figure 7.1 The best way to negotiate? Create competitive tension.

Chapter 8

Figure 8.1 Raising the next round.

Figure 8.2 Raising later rounds.

Chapter 9

Figure 9.1 Exits are a simple reversal of investment cash flow.

Figure 9.2 Share price movements after an IPO.

Figure 9.3 The impact of preference cascades at exit.

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright

About the Author

Acknowledgements

Begin Reading

Case Study Solutions

Index

End User License Agreement

Pages

iii

iv

vii

viii

ix

x

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

260

261

262

263

264

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

272

273

274

275

276

277

278

279

280

281

282

283

284

285

286

287

288

289

290

291

292

293

294

295

296

297

298

299

300

301

302

303

304

305

306

307

308

309

310

311

312

313

314

315

316

317

318

319

320

321

322

323

324

325

326

327

328

329

330

331

332

333

334

335

Building Value

The Business of Venture Capital

Simon Barnes

This edition first published 2025

© 2025 by Simon Barnes. All rights reserved

All rights reserved, including rights for text and data mining and training of artificial intelligence technologies or similar technologies. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by law. Advice on how to obtain permission to reuse material from this title is available at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

The right of Simon Barnes to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with law.

Registered Office(s)

John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, USA

John Wiley & Sons Ltd, New Era House, 8 Oldlands Way, Bognor Regis, West Sussex, PO22 9NQ

For details of our global editorial offices, customer services, and more information about Wiley products visit us at www.wiley.com.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats and by print-on-demand. Some content that appears in standard print versions of this book may not be available in other formats.

Trademarks: Wiley and the Wiley logo are trademarks or registered trademarks of John Wiley & Sons, Inc. and/or its affiliates in the United States and other countries and may not be used without written permission. All other trademarks are theproperty of their respective owners. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and authors have used their best efforts in preparing this work, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this work and specifically disclaim all warranties, including without limitation any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives, written sales materials or promotional statements for this work. This work is sold with the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a specialist where appropriate. The fact that an organization, website, or product is referred to in this work as a citation and/or potential source of further information does not mean that the publisher and authors endorse the information or services the organization, website, or product may provide or recommendations it may make. Further, readers should be aware that websites listed in this work may have changed or disappeared between when this work was written and when it is read. Neither the publisher nor authors shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Barnes, Simon, 1969- author.

Title: Building value: The business of venture capital / Simon Barnes.

Description: Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2025. | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Summary: “This book, rooted in Simon Barnes’ MBA courses on venture capital and his 25 years of industry experience, offers a practical insider’s perspective on venture capital. Aimed at first-time entrepreneurs and young VCs, it emphasizes that entrepreneurial finance is more about aligning interests and behaviors than numbers. The book includes four case studies, model term sheets, and examples illustrating share structures and deal negotiations, providing valuable insights into the venture capital process. It advocates for mutual understanding between entrepreneurs and VCs to create deals that build value with minimal conflict” – Provided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2024038847 | ISBN 9781394231898 (hardback) | ISBN 9781394231904 (epub) | ISBN 9781394231911 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Venture capital.

Classification: LCC HG4751 .B357 2025 | DDC 658.15/224–dc23/eng/20241017

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2024038847

Cover image: Thick fog covering Golden Gate Bridge. © Radoslaw Lecyk/Shutterstock

Cover design by Wiley

About the Author

Simon Barnes has worked in and around the venture capital industry since 1998, first with the London office of Atlas Venture, where he experienced the dotcom boom and subsequent bust first-hand. He spent time on the faculty of Imperial College Business School, London, co-authoring Raising Venture Capital before co-founding Circadia Ventures in 2005 to manage early-stage venture capital funds investing in life sciences, nutrition and industrial biotechnology. He has served on the boards of directors of numerous venture capital-backed businesses in the United States, United Kingdom and European Union. He holds an MA in Natural Sciences and a PhD in Molecular Biology & Biochemistry from the University of Cambridge and an MBA from Imperial College Business School.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Ben Barnes for his research into the history of the venture capital industry and for his assistance in preparing and reviewing this text. Thank you to John Lyon for enjoyable discussions about entrepreneurial finance and making teaching it fun.

Chapter 1Why Do Start-ups Raise Capital?

It might seem a strange question to ask at the beginning of a book about venture capital, where so much of the culture of the start-up industry appears to focus on ‘doing the next raise’. Of course, start-ups raise capital, that’s what they do, isn’t it? We are sometimes led to believe that the only goal for entrepreneurs or start-up CEOs is to raise money from venture capitalists (VCs). But ask yourself a fundamental question: Why? In the old days, entrepreneurs didn’t always do that, so why now? In the early part of the 20th century, companies which started small ended up being global corporations without huge amounts of capital being injected into them. With a sometimes limited number of informal backers, their management teams reinvested cash generated from hard-won sales to build companies step by step, often failing and restarting along the way. Was there a different entrepreneurial mentality necessitated by the scarcity of resources? Can we learn something important from the old ways? Reading even a small amount of literature on the history of business can be illuminating when seeking an answer to these questions.

The Ford Motor Company was a start-up once. Henry Ford began small with a few investors to form the Detroit Automobile Company. The company failed. The assets were bought out of administration by some of the investors, who allowed Ford to carry on as the Henry Ford Company. The company failed for a second time. For Henry Ford it was a case of third time lucky; the Ford Motor Company was formed with investments totalling $28,000 in 1903. The early investors in the Ford Motor Company included a successful Detroit coal merchant and the director of a well-regarded bank. These individuals were not professional VCs, they were private investors with a sense of adventure and a vision of the future. The company operated with very little resource; Henry Ford himself didn’t take a salary and was adept at persuading others to work for very little. This approach, raising money where he could and stretching very limited resources, eventually led to the successful global corporation we know today. The early investments into Ford’s various attempts to launch were not from modern-style venture capital funds, but piecemeal investments from a group of business owners and managers who took a chance and eventually made remarkable returns (Brinkley 2004). Tight financial control and careful business practices were the secret to Ford’s early success, before the exponential growth of the Model-T powered the business to profit.

Countless other early 20th-century success stories took decades to become the global corporations they are now. Throughout history, ‘start-ups’ (before they were really called that) often grew slowly and organically, and sometimes independent of a financing industry that was simpler and more limited in scope than it is today.

By injecting substantial amounts of external funding, the modern venture capital industry confers upon start-ups the ability for time travel, accelerating through the difficult early years of product development and business model experimentation. It affords start-ups the ability to try designs and test markets and business models via trial and error or the scientific method now termed ‘lean start-up’, and build world-class management teams to execute aggressive growth plans, including the acquisition of smaller competitors or suppliers. Technology means that the pace of innovation is quicker than it was in Henry Ford’s day, and the race to conquer unique business opportunities before others is conducted at break-neck speed. The venture capital industry provides the fuel to grow fast…

Asset Parsimony

In a 1984 academic paper, Donald Hambrick and Ian MacMillan coined the term asset parsimony, namely ‘skill at deploying the minimum assets needed to achieve the desired business results’ (Hambrick and MacMillan 1984). Their paper focused on return on investment (ROI) and pointed out that investing heavily in assets upfront, without understanding the risks and the payoff, can rapidly pave the way to the bankruptcy court. This is not a complicated concept, and most will agree that it is intuitive to most experienced managers, but it is surprising how few entrepreneurs (and VCs) adhere to this business philosophy today.

Raising finance for start-ups is a time-consuming and expensive process. More favourable conditions for raising finance are best achieved by having a compelling investment opportunity, supported by evidence of technical progress and a scalable business model, before approaching investors. Demonstrating an ability to make sales, strike deals or at least generate interest from potential customers (often referred to as ‘traction’) is a key aspect of convincing investors that this is more than ‘an idea’. In other words, it’s ‘best foot forward’ before attempting to raise capital. Entrepreneurs should go as far as they can before attempting to raise money for the first time; maximise the utility of assets at hand; and beg, borrow and salvage until the business is ready and sufficiently attractive to raise investment on the most favourable terms.

This thought process should be nailed to the wall of every fledgling start-up business – achieve as much as you can and deliver tangible value before engaging with the investment community as this will enable you to raise more capital, on better terms and with less time and energy.

In recent years, asset parsimony seems to have been forgotten by entrepreneurs. The culture within the technology-based entrepreneurial community seems to have been the opposite – raise as much money as you can, as fast as you can, on as little progress as possible and invest heavily upfront. This has been possible for some entrepreneurs in the tech industry as venture capital markets have been awash with capital for extended periods between 2012 and 2022 – technology markets have been hot and venture capital funds swollen by historically low global interest rates. This is discussed in more detail later in the book, but for now the key lesson is that during times of plentiful venture capital, the ‘culture’ of start-ups shifts to fashionably large funding rounds and away from the grit of the hard-bitten entrepreneur who understands what it means to survive tough times.

The Best Time to Raise Money is When You Don’t Need To

Seemingly paradoxical to the concept of asset parsimony, experienced entrepreneurs know that the best time to raise money is when you don’t need to. The asset parsimony approach has one flaw: it assumes a steady supply of investment capital on constant, stable terms that do not change. For start-ups especially, this is not true. Market conditions in general can change overnight, but sentiment towards a particular sector in venture capital can disappear even faster – in the blink of an eye. There is no point frugally and methodically working to achieve proof of concept, and then going out to raise capital just as the financing climate turns sour.

Getting the timing right, therefore, plays a huge role in raising capital. Experienced entrepreneurs are constantly alert to the possibility of external investment, because the most favourable terms are achieved when they don’t really need the money. When the bank balance is healthy, entrepreneurs have the luxury of walking away from an investment offer, and that makes investors more eager to invest, driving up the price of the deal. It is easier to negotiate price when you don’t need investment urgently…

Putting aside negotiation tactics, experienced entrepreneurs usually think very carefully before turning down investment offers, even when they are not looking for funding. They are also open to accepting more investment than they are asking for in their business plan or pitch. It is usually the case that early-stage ventures run into delays – be they technical challenges or commercial hurdles – and having a cash buffer for unforeseen events can be a life saver for the company.

In conclusion, the seemingly paradoxical ‘go as far as you can on as little as possible’ and ‘raise money when you don’t need it’ is not a paradox at all. Entrepreneurs need to respect asset parsimony with the knowledge that many a failed entrepreneur has turned down external investment for fear of dilution, and then gone bust when the climate changes. Balancing these twin pressures of making progress in a changing financing climate is a core skill for entrepreneurs. There is no universal solution to balancing this risk, just an awareness of the issue and an acknowledgement of one fundamental truth – a company that runs out of cash is bankrupt. So, the overriding force in all of this is making sure the company is funded and sometimes that means raising investment when you can.

Take money when you can get it, but respect asset parsimony.

Crossing the Valleys of Death

Revisiting our initial question, ‘Why do start-ups raise capital?’, it is reasonable to assume that new ventures generally spend money before they earn it. Investment in research and development, hiring personnel and embarking on expensive marketing campaigns all occur before the company has generated revenue. These activities result in cash flowing out of the company, sometimes for an extended period, before the first revenues are generated.

If we view this as a cumulative cash-flow chart (see Figure 1.1) we arrive at a generic picture, the so-called ‘Valley of Death’, a well-known concept in the field of entrepreneurial finance. For any given start-up, cash declines as the business invests in R&D, product development and so on, until sales begin and revenue (and subsequently cash) starts to climb. The point at which cash flow turns positive marks the lowest point in the Valley of Death, the most negative ‘bank balance’ the business will experience as it grows towards a profitable ‘Promised Land’ in which cash is generated to be used for further growth. Most start-ups fail somewhere in the Valley of Death, not because their ideas were inherently wrong, but more often because they ran out of cash before reaching the other side.

Figure 1.1 Financing the journey to the Promised Land.

The total amount of finance required for the company to reach the Promised Land is the distance between the curve and the x-axis; in other words, the lowest point in the cumulative cash flow (bank balance). Raising capital shifts the curve upwards so that it never crosses into negative values and keeps the company solvent, illustrated by the dashed line. The capital raised by an entrepreneurial team should be based on this logic with a buffer for delays and not, as is often the case, a simple desire to raise as large an amount as possible…

The function of the venture capital industry, and other early-stage investors, is very simply to enable start-ups to cross the Valley of Death. According to our Valley of Death cash-flow chart, the amount of capital required by the start-up ought to be dictated by the lowest point in the valley – in other words, a capital injection at the beginning that shifts the curve upwards so that the lowest point touches the x-axis and prevents the bank balance straying into negative territory.

Of course, life is never as simple as that, at least in the world of entrepreneurial finance. The Valley of Death is often shrouded in fog, making it almost impossible to see the bottom or the other side of the valley. A faint glimmer of a possible foothold to clamber out of the chasm is sometimes as good as it gets. VCs are familiar with management teams telling them that the turning point is imminent, only to find that they have not reached the bottom at all, and in fact they are only half-way down, or some seismic shift has made the valley deeper, wider or both. In some cases, even as revenues grow and the business nears the Promised Land, new and unexpected valleys may appear from the fog. A contract is lost, a technology fails, a competitor appears or a regulator imposes new requirements on the product. This section was titled ‘Crossing the Valleys of Death’ (in the plural) for a reason, as entirely new valleys may open before the management team’s eyes (see Figure 1.2). Plans are revised, budgets revisited and, inevitably, fresh funding is required to cross the newly appeared valley. So, it goes on…

Figure 1.2 There are multiple Valleys of Death.

To the surprise of entrepreneurial teams and investors alike, just as things are picking up there is a setback, perhaps technical, perhaps commercial and sometimes people related. This can plunge the business into a second or third Valley of Death. They may end up bumping along the floor of a very wide and seemingly endless valley. This presents the entrepreneurial team with a never-ending question: how much to raise? Balancing a financial safety net or financial buffer with the dilution of raising too much capital is an ongoing debate in all entrepreneurial management teams.

A close colleague and friend, Professor John Lyon, describes ‘the uncertainty of entrepreneurial finance’ as the third certainty in life, alongside death and taxes’. This is a lesson well remembered by all who have travelled through the multiple Valleys of Death, and even more so by those who never made it out. This reinforces our earlier conclusion about respecting asset parsimony but taking money when you can get it – entrepreneurial teams never really know what is around the next corner and an unexpected adverse event can spell the end of the business, or at the very least a requirement for new finance in distressed circumstances.

Wise entrepreneurs raise more than they need in anticipation of setbacks that will almost certainly come…

Is it Just the Money?

Ask an experienced entrepreneur why they raised venture capital, and they will tell you it’s not just about crossing the Valleys of Death or speed to market. It is not simply ‘the money’. It is about what else the VCs bring: credibility, networks, experience, reputation and (importantly) access to further capital and financial services such as investment banks and the best accountancy and law firms. They serve as guides within the financial ecosystem and can help start-ups avoid the blind alleys that lie along the way to reaching a profitable outcome. The venture capital industry calls this money plus and this may be the real reason why start-ups should raise money, perhaps even if they don’t need to.

The credibility associated with raising capital from a highly reputable VC can make a considerable difference to the fortunes of an otherwise unknown start-up (see Figure 1.3). Start-ups effectively buy themselves legitimacy. A press release from a well-known VC fund that has invested in company XYZ is an important moment – suddenly, potential customers and suppliers return calls and emails from company XYZ; the number and quality of applicants for roles at company XYZ increases; everyone wants to work there. And most importantly, other investors come calling and what was previously a drought of financial interest turns into a monsoon. VCs hate nothing more than missing an opportunity, and if a reputable VC announces an investment, the first question other VCs ask themselves is ‘Why didn’t we see that?’. At that point it’s probably too late for them to invest in the current financing round but they will certainly be aiming at the front of the line for the next round of financing when it occurs.

Figure 1.3 The credibility carousel.

Raising money is not just about crossing multiple Valleys of Death. It is about acquiring credibility via the backing of reputable investors. Raising capital from a well-known and well-regarded VC can enable a start-up to benefit from the halo effect of their reputation. Prior to raising money, the start-up suffers from the liability of newness in which it is difficult to gain customers and suppliers, rent premises and hire staff. Sue Birley, a Distinguished Professor on the MBA programme at Imperial College London’s Management School taught many years ago that money is often the ingredient that breaks the ‘credibility carousel’. This is a lesson that has been borne out time and again, and reputable money is best of all…

Reputation is everything in the world of entrepreneurial finance. Research has shown that entrepreneurs will accept less favourable investment terms (a lower price per share) to raise capital from a VC with a particularly strong reputation. For the reasons above, entrepreneurs will trade precious equity in their start-up for the non-monetary value that such VCs bring via their reputation and track record. This is often referred to as ‘paying for association’, and a number of researchers have attempted to measure how much additional equity entrepreneurs will give up just to get a really well-known VC on board. We should not read too much into the precise quantification of this trade-off – it will vary from industry to industry, across regions and over time – but it is safe to conclude that entrepreneurs expect extra value, or ‘money plus’, from highly reputable VCs and are prepared to surrender additional equity in return.

Do VCs really add the value they claim and for which entrepreneurs are prepared to ‘pay for association’? That is a question we will deal with in more detail later in this book – opinions are split within the entrepreneurial community and there is research to support arguments for and against. Later chapters will refer to this question and discuss the often complex and conflicted role that VCs play on the board of directors in start-up companies.

Supply and Demand

The final part of the answer as to why start-ups raise finance is, of course, because they can. The venture capital industry has evolved into a global industry, which itself depends on start-ups as its raw material. The venture capital industry needs to invest in start-ups because that is the business model they sell to their own shareholders, termed Limited Partners (LPs) (for reasons we will examine later in this book). Numerous VCs have raised increasingly large funds and there is pressure to invest the money they have raised. They look aggressively for ‘deal flow’ (opportunities) to deploy their capital into, and there is competition to find the best deals and generate the best returns for their LPs.

The delicate balance between the supply of venture capital and the demand from start-ups creates a finely tuned global innovation engine. When this global innovation engine is in balance, it has the potential to operate at high speed, generating wealth and providing solutions to some of society’s biggest problems, some of which we didn’t even know we had. When supply and demand is out of balance, it may lead to catastrophe as over-egged venture-backed companies or entire sectors fail to deliver. The peaks and troughs observed on the NASDAQ index since 1994 (see Figure 1.4) illustrate clearly how market sentiment towards technology and science-based companies rises and falls with alarming frequency – a proxy for the returns generated by the venture capital industry.

Figure 1.4 The NASDAQ is a good proxy for the state of the venture capital market.

From the inception of the NASDAQ index, the value of stocks for technology-based businesses has shown remarkable growth but it has been a bumpy ride. The approximate dates for the launch of several well-known companies are marked, as are three key global events in the financial world: the dotcom crash of 2000, the financial crisis of 2009 and the COVID-19 pandemic. Entrepreneurial teams raising capital faced a very different financial climate depending on timing…

Any economist will confirm that supply and demand is a fundamental economic truth and many market phenomena may be explained this way. Venture capital is no different. There are periods of time, such as the decade following the financial crisis of 2008–2009, in which quantitative easing by central banks around the world fuelled the expansion of the venture capital industry as investors sought returns in riskier assets, which led to increased supplies of venture capital seeking opportunities. The demand for venture capital arguably failed to keep up, at least with the same quality, and eventually 2022 saw a sharp reversal as VCs turned off the taps, leaving an unsatisfied demand for venture capital following an overinflated entrepreneurial bubble.

Summary of Chapter 1

This opening chapter has attempted to provide an overview of the entrepreneurial financing environment from the perspective of both entrepreneurs and VCs. It has focused on crossing the Valleys of Death and the principles of ‘money plus’ – in other words, seeking additional value from investors who back growing businesses.

Entrepreneurs should not raise money for the sake of it; this is not the goal, it is the means to reach the goal – a profitable enterprise. Although we now live in a world with a large and sophisticated venture capital industry to fuel the global innovation engine, perhaps we can learn something from the ‘old ways’ when entrepreneurs built businesses in tough financing climates with precious few resources. This seems an obvious statement to make, but it is surprising how many entrepreneurs (and VCs) forget this in the frenzy of a hot financing climate.

By the time you read this book, other global events will no doubt have had their impact on the financial markets, and reading the following chapters in context will be important. Depending on the supply and demand for venture capital finance, some terms and deal structures will be more (or less) prevalent, but the core principles never change.

Respect asset parsimony, raise money when you don’t need to, raise more than you think you need and raise with money plus as your priority.

References

Brinkley, D. (2004).

Wheels for the World: Henry Ford, His Company and a Century of Progress, 1903–2003.

New York: Penguin Random House.

Hambrick, D.C. and MacMillan, I.C. (1984). SMR forum: Asset parsimony –managing assets to manage profits.

Sloan Management Review

25 (2): 67–74.

Chapter 2Equity and the Art of Milestone-Based Financing

In the previous chapter, we examined some of the basic characteristics of the world of entrepreneurial finance, beginning with the question ‘Why do start-ups raise capital?’ We explored the idea of asset parsimony and how the changing fortunes of the financial climate will impact the ability of entrepreneurs to raise finance and cross multiple Valleys of Death.

In the current chapter, we will examine the key principles underpinning the entrepreneurial financing journey, the forms and sources of investment entrepreneurs might access and the way in which the venture capital industry views its own world. Only by understanding the business model of venture capital funds and the fund managers who operate them can entrepreneurial teams navigate the financing journey with optimal results. Key to this is understanding the basic principle of equity and the concept of milestone-based financing which sits at the core of the entrepreneurial finance world.

The Equity Pie

Ask any class of undergraduate students where entrepreneurial start-ups should raise finance and one of the first answers will usually be ‘get a loan from a bank’. Banks do not, however, make loans to high-risk companies with unproven technologies, business models and management teams. Small businesses such as shops, local services and cash-generating ventures seeking to expand and open a new branch based upon a track record of solid financial results may access bank loans (think of a reputable and successful hairdresser opening a second branch in a neighbouring town) but pioneering entrepreneurs seeking to change the world cannot usually persuade a bank to back a high-risk, unproven idea with a loan.

Such entrepreneurs, aiming to disrupt markets and build big businesses, are faced with a simple solution: raise equity finance. Entrepreneurial teams need to sell a share of their start-up company to investors who are prepared to back it at great risk. Such investors must be prepared to lose their entire investment in the start-up if it fails but hope to share in enormous returns if it succeeds. This is the business of venture capital in a nutshell and equity is its currency.

Just as the shares of established companies are traded on various stock exchanges around the world, changing hands readily via intermediary market-making stockbrokers, so too can shares in start-ups be sold. Selling equity simply means selling a portion of ownership (or shares) in the company, and the first question which springs to mind is how much? What portion of the equity pie (i.e. how many shares) must the founders of the business sell to raise the finance they need to build it and what conditions are attached to that sale?

How big a portion of the equity pie is sold, and at what price, is the subject of Chapter 6, where we examine valuation (or pricing) of venture capital deals. For now, it is enough to say that the valuation of start-ups is more art than science. Formal valuation methodologies do not work very well for high-risk, early-stage ventures and the valuation is determined by the market: how much investors are prepared to pay for a piece of the company based on their views of the risks and returns and the supply and demand for venture capital. But what constitutes the market for shares in start-ups and who are the participants? Who buys and sells equity in start-ups and how do these transactions occur? What is the process and how are the deals structured? These are all issues that we will address throughout this book, and the aim is to unpick the activities of the venture capital industry from the perspective of both entrepreneurial teams and the VCs who back them.

Equity is the currency of entrepreneurial finance; the question is, who are the buyers?

Private Equity and Venture Capital

When shares are sold directly by a privately owned company to a buyer, we call this ‘private equity’; a private contract to sell shares as opposed to ‘public equity’ for larger corporations, in which shares are traded daily on a stock market. The venture capital industry is essentially a subset of the private equity industry, and the question is often asked, therefore, what is the real difference between private equity and venture capital, as the terms are sometimes used interchangeably? The answer is that whereas VCs specialise in buying equity in start-up and early-stage companies, the wider private equity industry usually focuses on established businesses with revenues and cash flows, and often uses debt alongside equity as part of its financing mix.

It is important to note here that starting a company is not the only route to owning one. Some entrepreneurs buy pre-existing companies, sometimes when the current owners retire and often to turn them around or combine them with other assets. When managers buy the company they currently work for, we term this activity a management buyout and when they buy external target companies, we refer to this as a management buy-in. Both are important routes to ownership supported by private equity funds but are beyond the scope of this book.

The goal of private equity is often to turn around underperforming companies, unlocking the value within their assets and exploring new markets and geographies with a proven business model. There is often a lot of financial engineering and the use of debt to leverage the assets of the target company. Venture capital, on the other hand, focuses entirely on start-ups and early-stage companies, where almost everything is unproven. VCs are taking a holistic view of the opportunity, there is almost no financial engineering – it is pure equity. Although we will explore preferred shares and preference shares used by VCs later in this book, the share instruments and financial structures used in venture capital are relatively simple compared to private equity, and indeed VCs and private equity fund managers often appear to speak a different language. Sometimes, however, private equity funds overlap with venture capital funds when growing ventures become sufficiently cash-generative for the private equity industry to step in and take a stake, often with a specific exit goal in mind.

Figure 2.1 shows the relationship between private equity and venture capital. It is worth noting that buyouts use a combination of equity and debt. Management buyouts, buy-ins and very large ‘leveraged buyouts’ target companies with established businesses and reliable (but likely underperforming) business models. These transactions use debt because the risks are lower, and the business has sufficient free cash flow to service debt. Start-ups are different. They have little or no cash flow, and rarely have a proven product, business model or even management team. Debt is off the table and equity financing is the instrument of choice.

Figure 2.1 The private equity spectrum.

Venture capital forms a subset of the private equity spectrum and focuses on start-ups and early-stage ventures. Venture capital funds are generally much smaller than private equity buyout funds, which target established businesses, usually with the goal of turning around underperforming assets. Venture capital funds invest in pure equity and rarely use debt, but buyout funds are different. Management buyouts (MBOs), management buy-ins (MBIs, in which external management teams buy a company) and leveraged buyouts (LBOs, which are very large buyouts) use debt as a source of capital in their financing mix. The debt is repaid from free cash flow within the target company over several years, leaving the equity holders as the owners of a debt-free company. This is an oversimplification of a complex industry, but the key principle is that VCs, business angels and friends, family and fools (FFF) are all a subset of the wider private equity market.

This book focuses on the role of the venture capital industry in investing in start-ups, but VCs are not the only source of early-stage equity finance. New ventures often find that their first capital comes from other sources, some of which are informal and very close to home. Friends and family, business angels, accelerators and incubators and crowdfunding play a role in the early steps towards building a successful company.

Fools and Angels

Who would be unwise enough to buy shares in a start-up with an unproven technology, business model and management team? The entrepreneurial team’s extended friends and family might. In fact, the very first investment into start-ups frequently comes from those whose investment decision might go beyond the purely rational analysis of a VC; in other words, friends and family. This is often described, perhaps more accurately, as ‘friends, family and fools’. This is not meant to be derogatory; sometimes humans invest in other humans because they are related, because they like them or perhaps because they just want to help someone in a quest that means something to them personally – or they feel a connection. A quick scan of websites like gofundme.com or justgiving.com will illustrate just how generous people can be with a wide variety of causes: some charitable, some personal and others blatantly commercial.

This nudges us towards the notion of crowdfunding, which is a genre of early-stage funding that has grown enormously in recent years. Crowdfunding is nothing new and is in fact an old form of fundraising. The plinth for the Statue of Liberty in New York’s Upper Bay was famously funded by a proto-crowdfunding campaign organised by the New York Times. The ‘new’ aspect of crowdfunding is that it has been enabled and expanded by the internet, opening early-stage, high-risk investments to a wide variety of investors. Fans of crowdfunding refer to the democratisation of venture capital investing, opening the market and providing access to high-return deals for ordinary investors.

Critics of crowdfunding, on the other hand, talk about the extreme information asymmetry existing between the promoters of new ventures on crowdfunding platforms and the inexperienced investors who back them. Information asymmetry is discussed later in the book; it is a fundamental function of the venture capital industry to manage the information asymmetry that exists between entrepreneurs and investors. Entrepreneurs know a lot more about the risks of their business than the investors who back them. In the case of crowdfunding, there are very few if any means to manage this information asymmetry and investors are exposed directly to a wide variety of pioneering ideas that carry enormous risk. Some commentators argue that such investors rarely have the skills and experience to know what they are getting into and should proceed with extreme caution. Buyer beware is nowhere more evident than in the world of crowdfunding…

Business angels are dealt with in other texts, such as Richard Hargreaves’s practical guide Business Angel Investing (Hargreaves 2021), but suffice to say they form an important component of the early-stage entrepreneurial financing journey. The term ‘business angel’ covers a variety of investors, from individual high-net-worth investors (the classic view being successful entrepreneurs reinvesting their great wealth and experience into new ventures) to smaller participants investing $10,000 or less. Indeed, Scott Shane, in his book Fool’s Gold, points out that most angel investors in America are much smaller and play a less prominent role than popular views would have us believe (Shane 2008). Whether large or small, however, the key word for business angel investors is ‘experience’. Just as VCs offer money plus via their experience, networks, connections and reputation, the same is true of the best business angels–whatever their quantum of investment.

Raising capital from an angel with a great track record and reputation in a particular field has value beyond the dollars they put in. It is worth highlighting the subtle difference here from a high-net-worth investor who has amassed wealth through some other means, be it investment banking, sports, fame, celebrity, inheritance or even a major lottery win. They may be able to invest in a start-up but whether they can offer the same ‘money plus’ as an individual who has built and sold an entrepreneurial venture is a matter for debate. The operational experiences of a successful entrepreneur turned angel is often the true value of angel investing.

The single item that binds all these angels together and sets them apart from VCs is that they are investing their own wealth. Contrast this with VCs who, as will be discussed later in Chapter 4, are professional fund managers investing other people’s money with specific targets in mind and timelines to adhere to. Business angels can have more flexibility in their timelines to exit, but having no clear guidelines can have its own downsides. Sometimes angels write their own rules and that can lead to challenges later in the entrepreneurial finance journey.

It has sometimes been said that ‘if they were really angels they wouldn’t be where they are today’. This is a deliberately provocative comment designed to make a point – and it is this: entrepreneurial teams need to know the investors they are dealing with, how they behave and what their business model is. The venture capital business model is relatively simple to understand and almost uniform across different funds and different countries. This is not the case with business angels, who are sometimes unpredictable and occasionally present challenges for a growing business seeking to raise venture capital.

Sometimes business angels organise themselves into networks or groups with professional procedures, structures and the reputations to go with them. These business angel networks often hold regular pitching events, and lead investors within the group will nominate and sponsor start-ups through the investment process. Such groups often coordinate their investments through standard investment agreements and may have one individual (the lead investor or sponsor) who is mandated to sign documents on behalf of all the angel investors who participate in a round. This makes deal management much easier for the entrepreneurial team, who no longer must deal with multiple business angels when they need shareholder consent for major corporate decisions.

VCs find it easier to invest in companies that have raised angel finance from organised business angel networks or groups rather than individual angels. This is because the business angel networks use more recognisable terms and construct deals that neatly dovetail with later venture capital rounds. Often, smaller VCs will co-invest with established business angel groups in a cross-over round as the company transitions from the early angel rounds to larger venture capital rounds. Contrary to some commentators’ views, VCs and business angels can co-exist very easily and provide a smooth transition through the funding rounds – to be discussed later in this chapter.

Incubators and Accelerators

Prior to the dotcom boom it was difficult to come across something that could be described formally as an ‘incubator’ or an ‘accelerator’. Up until that time there were informal arrangements, mostly within universities where start-ups would be housed for free, consistent with the asset parsimony concept discussed in Chapter 1; there was a mindset of beg, borrow and salvage that included free space and access to facilities provided by the parent organisation. It was investment in kind, although some universities developed spinout funds to back companies developed within their instructions and using their intellectual property. In the United Kingdom, the University of Manchester was an early proponent of the model, with the formation of the Manchester Bio Incubator at the end of the 1990s.

After 2000, a legacy of the dotcom era was the notion that an organised approach to company creation could be a lucrative business if carried out correctly. The incubator model began to spread within universities and then into the private sector. Incubators began to operate as landlords housing their own start-ups (known as spinouts), sometimes for rent payable in cash and sometimes with the expectation of equity when the business raised money from investors. They began to tack on advice, professional services and in some cases small amounts of seed funding.

Accelerators arrived a little later, and it is generally recognised that this sector began with the launch of Y Combinator in 2005 and TechStars in 2007. The industry has grown substantially and at the time of writing this book, accelerators appear to be almost ubiquitous – operated with varying degrees of success by universities, national and regional governments, groups of investors who club together behind an independent accelerator and numerous corporates as part of their open innovation strategies. Although there is an overlap in the operation of accelerators and incubators (both offer mentoring and planning, office and technical facilities, and sometimes funding), accelerators differ in their ‘admissions’ policy. They tend to operate like a quasi-educational programme, offering admission to companies as a cohort for a fixed period, putting them through a mentoring programme with a defined endpoint or ‘graduation’ rather than the tenancy approach of incubators, where the endpoint is loosely defined.

Some accelerators offer investment upon ‘graduation’ and others run a competition, with the winners receiving investment in cash or in kind through further mentoring services. Accelerators often charge fees for their programmes, either in cash or in kind via equity – they are in effect acting like early-stage VCs, acquiring equity in a portfolio of hand-picked start-ups that they nurture and accelerate. Accelerators may be viewed as a bridge between incubators and the external investment industry (both angels and VCs) but the overlap is now substantial, as incubators and accelerators have migrated towards each other by adopting aspects of each of their business models.

Both incubators and accelerators (and the hybrids that exist between them) are a viable and important source of finance for start-ups. They go some way to filling part of the equity gap left by VCs as they migrate to more lucrative, large fund sizes and provide a more formal source of finance than friends and family rounds.

Selling Equity is Expensive

Selling equity is an expensive business. Selling equity doesn’t just mean raising money, it means selling ‘upside’ in the business – a substantial share of the future success. Perhaps more importantly, it means surrendering control. The founders’ ownership is diluted when the company raises equity finance, the magnitude of their dilution being determined by the valuation (share price) of the transaction. Valuation and pricing of equity is discussed in detail in Chapter 6. Not only does this mean sharing the economic benefits of future success, it also requires an acceptance that there will be other voices to be heard in discussions about the strategic direction of the business, both via appointments to the board of directors and via shareholder vetoes (discussed in Chapter 7).

When VCs buy equity in start-ups, they usually require a seat on the board of directors, this being part of their ‘money plus’, delivering additional value beyond the cash investment discussed in Chapter 1. There are, however, other mechanisms through which they exert some degree of control over the businesses they invest in. The right to exercise shareholder vetoes over key decisions such as spending, board appointments and the use of preferred or preference shares to enable their rights are all aimed at exercising control beyond their simple percentage equity stake. In other words, even if the founders and shareholders surrender less than 50% of the equity ownership in return for investment from VCs, they will not be able to make decisions without the VCs’ approval by virtue of board and shareholder rights. Retaining more than 50% of the equity does not mean the founders can ‘outvote’ their new investors. The imbalance of power is designed by VCs to address what they see as information asymmetry in favour of the founders and management team. By holding the balance of power via their board seat and shareholder veto rights, their aim is to prevent founders and management forcing decisions they are not comfortable with.

This dynamic evolves as the business grows and raises further rounds of finance, with new investors joining the shareholder register and obtaining board seats and shareholder rights. Often, shareholder rights are awarded to classes of shares such as the preferred shares sold in the first venture capital round, often termed ‘Series A’, or the second venture capital round, ‘Series B’ (see later in the chapter for a discussion of the terminology of investment rounds). By spreading shareholder veto rights among a variety of investors, the company at least avoids concentrating too much power within the hands of one substantial minority shareholder who may act in their own (possibly selfish) interests. Where these control ‘balance points’ lie is the subject of the shareholders agreement and is discussed in Chapter 7.

Founders must recognise, therefore, that selling equity in their start-up is not a purely financial transaction, like selling a house or selling a car; it is the beginning of a business partnership in which the partners are bound together for a period of years, through thick and thin, crisis after crisis, failure and success – until eventually they part ways at an exit event in which the VCs sell their shares. So, there is a long-term human relationship element to the venture capital investment, similar in some respects to a marriage – it’s best to make sure you get along before signing on the dotted line because the relationship will be strained at moments of stress, failure and disagreement. This is why entrepreneurial finance is a people business; it is less about numbers and more about behaviour. The biggest determinant of eventual success may not relate to the number of shares held by each party but how effectively they work together to make the best business decisions (see Figure 2.2).

Figure 2.2 Dividing the equity pie to align interests.

Selling equity to raise investment is like selling portions of an equity pie. Doing so means surrendering a portion of success and control in return for the investment needed to build the business. How the price of the slice is determined is the subject of Chapter 6 but suffice to say there is more art than science in this process for start-ups. An important and sometimes underappreciated aspect of this is achieving ‘felt fairness’ for founders, investors and other shareholders at the outset. A VC who negotiates too hard and squeezes the equity ownership of founders too much is likely to find this comes back to haunt them. If important groups of shareholders believe themselves to have been unfairly treated at the outset it is likely they will exact revenge at an important moment in the future of the company – often at the exit, when they are required to sign over the ownership of their shares. It is essential to align interests and motivations at the beginning to deliver the best exit in the future.