Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

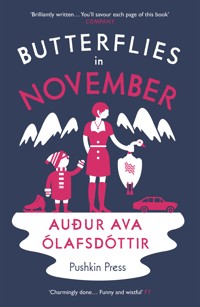

A hilarious and moving road trip around Iceland in an old car, told by a recently divorced woman with a five year-old boy 'on loan' After a day of being dumped - twice - and accidentally killing a goose, the narrator begins to dream of tropical holidays far away from the chaos of her current life. instead, she finds her plans wrecked by her best friend's deaf-mute son, thrust into her reluctant care. But when a shared lottery ticket nets the two of them over 40 million kroner, she and the boy head off on a road trip across iceland, taking in cucumber-farming hotels, dead sheep, and any number of her exes desperate for another chance. Blackly comic and uniquely moving, Butterflies in November is an extraordinary, hilarious tale of motherhood, relationships and the legacy of life's mistakes. Auður Ava Olafsdóttir was born in Iceland in 1958, studied art history in Paris and has lectured in History of Art at the University of Iceland. Her earlier novel, The Greenhouse (2007), won the DV Culture Award for literature and was nominated for the Nordic Council Literature Award. She currently lives and works in Reykjavik. "Quirky and poetic, everything is there... An extraordinary novelist" Madame Figaro "A poetic and sensory narrative" El País

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 433

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

AUÐUR AVA ÓLAFSDÓTTIR

BUTTERFLIES IN NOVEMBER

Translated from the Icelandic by Brian FitzGibbon

Dedicated to Melkorka Sigríður

Where are there towns but no houses, roads but no cars, forests but no trees?

Answer: on a map.

(Riddle on children’s breakfast TV)

Contents

ZERO

This is how it appears to me now, as I look back, without perhaps fully adhering to the chronology of events. In any case, there we are, pressed against each other in the middle of the photograph. I’ve got my arm draped over his shoulder and he is holding onto me somewhere—lower, inevitably—a dark brown lock of hair dangles over my very pale forehead, and he smiles from ear to ear, clutching something in his outstretched clenched hand.

His protruding ears sit low on his large head and his hearing aid, which seems unusually big and antiquated, looks like a receiver for picking up messages from outer space. Unnaturally magnified by the thick lenses of his spectacles, his eyes seem to almost fill the glass, giving him a slightly peculiar air. In fact, people turn on the street to gawk at him, staring first at him, then at me, and then pin their eyes back on him again for as long as he stays in view, as we walk across the playground, for example, and I close the iron gate behind us. As I help him into the seat of the car and fasten his safety belt, I notice we are still being watched from other cars.

In the background of the photograph, there is a four-year-old manual car. The three goldfish are writhing in the boot—he doesn’t know that yet—and the double blue sleeping bag is soaking wet. Soon I’ll be buying two new down duvets at the Co-op, because it’s not proper for a thirty-three-year-old woman to be sharing a sleepingbag with an unrelated child, it’s simply not done. It shouldn’t be any bother to buy them because the glove compartment is crammed with notes, straight from the bank. No crime has been committed, though, unless it’s a crime to have slept with three men within a 300-kilometre stretch of the Ring Road, in that mostly untarmacked zone, where the coastal strip is at its narrowest, wedged between glaciers and the shore, and there is an abundance of single-lane bridges.

Nothing is as it should be. It’s the last day of November, the island is engulfed in darkness and we are both wearing sweaters. I’m in a white polo-neck and he is in a newly knit mint-green hoodie with a cabled pattern. The temperature is similar to what it was in Lisbon the day before, according to the man on the radio, and the forecast is for rain and warmer weather ahead. This is the reason why a woman shouldn’t be venturing into the dark wilderness alone with a child, without good reason, least of all in the vicinity of those single-lane bridges, where the roads are frequently flooded.

I’m not presumptuous enough to expect a new lover to appear at every single-lane bridge, without wanting, however, to preclude such a possibility.

When I look at the picture in greater detail, I see a young man, a few steps behind us, about seventeen years old I would guess, between me and the boy, although his face is slightly out of focus. I discern delicate facial features under his cap and get the feeling he has bad skin, which is beginning to improve. He seems sleepy and leans against the petrol pump with his eyes half closed.

If one were to examine the photo in extreme close-up, I wouldn’t be surprised if there were traces of feathers on the tyres or bloodstains on the hubcaps, even though three weeks had passed since my husband walked out with the orthopaedic mattress from the double bed, all the camping equipment and ten boxes of books—that’s just howit went. But one needs to bear in mind that things are not always what they seem and, contrary to the dead stillness of a photograph, reality is in a state of perpetual flux.

ONE

Thank God it wasn’t a child.

I unfasten my safety belt and leap out of the car to examine the animal. It seems to be pretty much in one piece, totally unconscious, with a dangling neck and bleeding chest. I suspect a crushed goose heart under its oil-soiled plumage.

Papers flew out of their folders as I screeched to a halt, translations in various languages are scattered on the floor, although an entire pile of documents has remained intact on the crammed back seat.

The good thing about my job—and one of the perks that I never hesitate to remind my clients of—is that I deliver everything to them in person, drive over to them with proof-read articles, theses and translations, as if they were Thai noodle salads and spring rolls. It might seem old-fashioned, but it works. People like the tangibility of paper and, for one brief moment, to glimpse into the eyes of the stranger who has, in some cases, peered into the essence of their souls. It’s best to deliver right before dinner, I find, just as the pasta is reaching cooking point and cannot be left a second longer, or when the onion has been fried and the fish lies waiting on a bed of breadcrumbs, and the master of the house hasn’t had the good sense to turn off the heat under the frying pan before answering the door. In my experience that’s the quickest way to get through it. People don’t like inviting guests into a house smelling of food or to get sucked into a discussion with a stranger when they’re standing there in their socks or even bare-footed, in the middle of a narrow hallway crammed with shoes and surrounded by squabbling children. In my experience these are the ideal circumstances in which to settle a bill with the least likelihood of people trying to persuade me to knock off the VAT. As soon as I tell them I don’t take credit cards, they put up no resistance and swiftly write me a cheque and grab their delivery.

When people come to me in the small office space I rent down by the harbour, they normally give themselves plenty of time to ponder on my remarks and convince me of their good intentions, of their in-depth knowledge of the subject matter, and precisely why they decided to word things in the way they did. It’s not my job to rewrite their articles, they tell me, pointing out that in such and such a paragraph I skipped nine words, but simply to correct typos, as one of my customers put it, as he was adjusting his glasses and tie in the mirror in the hallway and flattening his kiss curls.

The idea wasn’t to oversimplify complex concepts, he says, the article is geared to experts in the field. Even though I had refrained from making any comments on his dubious use of the dative case in his Dam Project Report, I did wonder whether the word beneficial, which cropped up more than fourteen times on one page, might not occasionally be replaced by alternative and slightly more exotic adjectives, such as propitious or advantageous. This wasn’t something I said out loud, but simply a thought I entertained to perk myself up. Once these issues have been settled, some men like to say a little bit about themselves and also to ask some questions about me, whether I’m married, for example, and that kind of thing. On two or three occasions I’ve even toasted bread for them. I have to confess, though, that I didn’t write my ad. It was my friend Auður, who obviously got a bit carried away. Overkill isn’t my style:

I provide proof-reading services and revise BA theses and articles for specialized magazines and publications on any subject. I also revise electoral speeches, irrespective of party affiliations, and correct any revealing errors in anonymous complaints and/or secret letters of admiration, and remove any inept or inaccurate philosophical or poetic references from congratulatory speeches and elevate obituaries to a higher (almost divine) level. I am fully versed in all the quotations of our departed national poets.

I translate from eleven languages both into and out of Icelandic, including Russian, Polish and Hungarian. Fast and accurate translations. Home delivery service. All projects are treated as confidential.

I pick up the lukewarm bird I’ve just run over and assume it’s a male. By a cruel twist of fate, I recently proof-read an article about the love lives of geese and their unique and lifelong fidelity to their mates. I scan the flock in search of his widowed companion. The very last members are still waddling across the slippery icy road, towards the sidewalk on the other side, spreading their big orange webbed feet on the tarmac. As far as I can make out, none of them has stepped out of the flock to look for her partner and I can’t see any likely match for the bird I’m holding in my arms. I have, however, recently developed the knack for distinguishing black cats on the street from each other on the basis of their responses to caresses and sudden emotional reactions. The thing that surprises me the most, as I stand there in the middle of the road, still holding the fairly plump animal by the neck, is that I feel neither repulsion nor guilt. I like to think of myself as a reasonably compassionate human being; I try to avoid confrontation, find it difficult to reject requests delicately put to me by sensitive males, and buy every lottery ticket that any charity slips through my letterbox. And yet, when I go to the supermarket later on and stand there in front of the butcher’s slab, I’ll feel the same rush of excitement I get before Christmas, as I muse on the spices and trimmings, and wonder whether the pattern of the Goodyear tyre will be visible under the thick wild game sauce.

“Well then, good year to you in advance,” is what I’ll say to my guests at the surprise dinner party I’ll throw on a dark November night, without any further explanations.

I rip out several pages of a painfully tedious article about thermal conductors to place under the bird, before carefully lowering the carcass into the boot. It’s obviously ages since I opened it, because I discover that it is almost completely full of kitchen rolls that I bought to sponsor some sports excursion for disabled kids—a good job I didn’t opt for the prawns.

The goose won’t suffer the same fate, because I’m about to spring a fun culinary surprise on my husband, the great chef himself. First, though, I was planning on taking one last detour to an apartment block in the Melar district to do something I’d told myself I would never do again.

TWO

I park my car close to the block and rush up the threadbare carpet of the lily-blue staircase, tackling two steps at a time. I don’t allow myself to be bothered by the two or three doors that open during my ascent, ever so slightly, to the width of the vertical slit of a letter box, releasing the odours of well-kept homes. I don’t care if anyone can retrace my steps, because what I am about to do for the third time in three weeks is not a habit of mine, but a total exception in my marriage. When I rush out later on, I’ll be able to tell myself that I won’t be coming back here any more, which is why I can afford to be indifferent to those gaps in the doorways and prying eyes. I’m in a hurry to wrap my hands around my lover’s neck, standing on his newly laid parquet, and to run my fingers down the hollow of his neck, leaving a red streak in their wake, and then to get it over with, as soon as possible, so that I can buy the trimmings for the goose before the shops close. The most time-consuming task turns out to be the removal of my boots; he stretches to hold onto the door frame as I offer him one foot. He has removed his glasses and his eyes are glued to me throughout. The faint October sun, which is sinking over the tip of Seltjarnarnes, filters through the semi-closed slats of the venetian blinds, corrugating our bodies in stripes, like two zebras meeting furtively by a pool of water. I can sense from the waft of washing powder emanating from the bedclothes that he has changed the sheets. Everything is very tidy; this is the kind of apartment I could easily abandon in a fire or war, without taking anything with me, without any regrets. The only incongruous detail in the decor is the patterned curtain valances, concealing the top of the blinds.

“Mum made those and gave them to me when I divorced,” he says, clearing his throat.

Naturally, the environment is bound to change according to one’s moods and feelings, although I don’t want to get into a discussion on the notion of beauty and well-being right now. One can’t exactly say that there’s anything premeditated about the fact that I’m sitting here naked on the edge of this bed, nothing planned as such, it’s just the way my life is at the moment. I’m indifferent to the drabness or even perhaps ugliness of this apartment and I don’t mind that he sometimes spells hyper with an i or writes hidrodinamic fluid, and if he can be a bit vulgar in the way he talks or even inappropriate sometimes, it is because he has a firm and secure touch. Although I can’t really boast of any extensive experience in this field, I know there is no correlation between sex and linguistics, I’ve learnt that much.

A small feather has stuck to the bloodstain on the first page, but I don’t have to ponder on whether I should give him the article before or afterwards. I know from experience that it’s best to wait, business and pleasure shouldn’t be mixed. After we had slept together for the first time, he looked surprised when I handed him the bill with the VAT clearly highlighted.

After the deed, I help him smooth out the sheet, while he squeezes the goose-down quilt back into the stripy blue cover, which has slipped off the foot of the bed into a ball. He confides in me, sharing something a woman should never divulge. It is only then that I first notice the bizarre tattoo on his lower back. It vaguely resembles a spider’s web, which seems incongruous for a man of his social status. Skimming it, I feel the protuberance of a scar. When I quiz him about it, he tells me it was an accident, but I don’t know whether he is referring to the scar or the tattoo. He holds out his hand, clutching a pair of white lace panties between his thumb and index.

“Aren’t these yours?” he asks, as if they could be someone else’s.

I’m in a hurry to get home, but when I’ve finished washing my hands with his pink floating scented soap and step out of the bathroom, I see he has set the table, boiled eggs, buttered two slices of toast with salmon and made some tea for me. He is still topless and bare-footed and stands there, watching me eating, as he slips his shirt back on.

“I saw your car in town in the middle of the week and parked right beside it, didn’t you notice?” he asks.

Can’t say that I did.

“So you didn’t notice that someone had scraped the ice off your windscreen either?”

No, I didn’t, but thanks anyway.

“I noticed your car is due for an MOT…”

When I’ve finished both slices of toast and am about to say thanks and kiss him goodbye because I won’t be coming back again, he asks me how often I think about him.

Every three or four days, I say.

“That makes 5.6 times over the past three weeks,” says the newly divorced expert, who has only fastened one of the buttons on his gaping shirt. “I obviously think of you a lot more than you think of me, about sixty times a day and also when I wake up at night. I wonder what you’re up to, and watch you putting on your cream after the bath, trying to figure out what it must be like to be you. Then, in the evenings, I imagine you don’t slip into bed until your husband is asleep.”

My husband isn’t home much in the evenings these days.

Then he asks me if I intend to divorce him.

“No, that hasn’t entered my mind,” I say.

Because I probably love my husband. But I don’t say that. Then he bluntly tells me that this will be the last time.

“The last time that what?”

“That we sleep together. It’s too painful saying goodbye to you every time, I feel like I’m standing on the edge of a cliff and I’m scared of heights.”

It has grown eerily dark by the time I dash down the stairs of the apartment block for the third time in as many weeks. This time I’m gone for good and I will never again do what I’ve just done, I’m in a hurry to get home. Even if it is unlikely that anyone is waiting for me there. Driving, I listen to Mendelssohn’s “Summer Song” on the car radio. It’s an old crackly recording, but the presenter doesn’t seem to notice, not that I’m really listening to it.

THREE

Although no woman can ever fully map out her life, there is, nonetheless, a 99.9 per cent chance that I will end this day at home in bed with my husband. And yet, to my surprise and precisely when I’m in a hurry to get back home, I find myself reversing my four-year-old manual car, with some difficulty, into a parking space close to my old house on the street I lived on two years ago. The curtains look unfamiliar to me and I suddenly remember I no longer have a key to this front door, that I’ve moved twice since I lived here, without, however, moving very far. As I’m about to drive away from the house, I see they’ve hung a crib mobile in the room that once hosted my computer. To be absolutely sure of it, I wait until I see a man walk past the window with a little baby on his shoulders. At least I know it’s not my husband, nor my child. Because I don’t have a child.

I’m still in the car when the phone rings. It’s the music teacher and pianist, my friend, Auður. She is a single mother, and has a four-year-old deaf son and is now six months pregnant again. In the evenings she sits up on her bed playing her accordion and rarely says no to a glass of brandy, if the opportunity presents itself.

She tells me she can’t talk long, because she’s busy dealing with a difficult pupil and an even more difficult parent, but it so happens, she adds, almost lowering her voice to a whisper in the receiver, that she has booked but can’t go to an appointment with a fortune-teller, although not exactly a fortune-teller, she says, more of a medium, and would I like to go instead of her? I hear someone crying behind her, but can’t make out whether it’s a child or an adult.

She stumbled on this medium on a whim two years ago and since then has been firmly entangled in the web of her own destiny; nothing that happens to her catches her unprepared any more. At least the child came as no surprise.

I’m still waiting for the baby to disappear. I don’t think about it. That’s how I make it disappear, by not thinking about it. Until it stops existing. I can’t say I never think of it, though. I’ve looked it up in a book and know that it is no longer a 2.5-centimetre creature with webbed feet and that it has started to take on a human form, that it has developed toes. Soon I won’t be able to fit into my flower-embroidered jeans. I hide it under my woollen cardigan with brass buttons so that no one will notice it, so that no one will know. Soon I will be going out into the world. When I’ve finished school. It’s all still purely imaginary.

Auður knows my scepticism regarding fate.

“What do you mean you’d rather not? There’s a two-year waiting list,” she blabs on, as if she were trying to firmly and rationally deal with a capricious child. “They say she’s the absolute best in the northern hemisphere, they’ve been doing tests on her in America with brain scans and electrodes and stuff and they just can’t figure it out, can’t find any pattern, no thread, you’ve got to be there in twenty minutes on the dot, so you need to get going right now. It’ll cost you 3,500 krónur, no credit cards, no receipts. If you let an opportunity like this slip by, you’ll never get a chance again.”

She has to stop talking now, but will call me later to hear how it went, she whispers in a hoarse voice, before hanging up.

FOUR

Twenty minutes later, here I am out in the middle of a new estate on the outskirts of the city, once more on my way to the house of a stranger. The neighbourhood is in mid-construction and stretches out flatly in all directions under a high sky, with patches of marshland here and there, and little to shelter the houses. It takes me a good while to find the half-finished house. The streets are barely discernible and devoid of lamp-posts, house numbers or names, chaos seems to reign with all the randomness of the first day. But at least construction seems to have started on a church. What finally draws my attention to the right house is a pile of small pieces of wood in the driveway, tidily arranged to form a bizarre pattern, some kind of broken spider’s web that must have required some thought. Scaffolding still covers the façade and the lawn is strewn with stones and, no doubt, berries in the summer.

She is nothing like the image I’ve built up of a fortune-teller and reminds me of an Italian sex bomb from the sixties. It’s Gina Lollobrigida in the flesh who greets me at the door, without me remembering having knocked, looking stunning and of an indeterminate age, wearing a close-cut dress and high heels. What distinguishes her from the common fold, though, are her piercing eyes and tiny pupils, pinheads in an ocean of shimmering blue.

Inside, the house is almost empty. Naked light bulbs dangle here and there, a few plastic flowers, an image of Christ with pretty curly locks and big blue eyes welling with tears. On one wall there is a pencil drawing of a tall Icelandic turf house with four gables. Despite the mounting darkness outside, the house seems full of light. The woman’s voice is as charming as she is:

“I was expecting you earlier,” is the first thing she says to me, “months ago.”

Her spell works on me and my thoughts immediately become transparent. Pinned to the sofa, I feel the muscles relaxing around my neck. I rest my head on the embroidered cushion and ask whether she minds if I lie down, instead of sitting opposite her at the table.

She constantly shuffles an old deck of cards and arranges them on the table, counting and pairing numbers and suits, my past and future. She can obviously read me like an open book. I find it quite uncomfortable to be browsed through in that way. But she makes no mention of adultery or the dead goose in my boot, and doesn’t talk about what must be written all over my forehead, that I’m still carrying alien liquid inside me that I fear could leak onto the velvet sofa.

Instead she focuses on my childhood and other things I’ve no memory of and know nothing about. She mentions mounds of manure and the broken elastic of some skin-coloured breeches, and keeps on coming back to the torn thread, they could be underpants, she says, cream-coloured, or they could be a pyjama bottom. I don’t know where she’s going with this.

“I’m just telling you what the cards show me, hang on to it.”

Then, in the same breath, she turns to my future.

“It’s all threes here,” she says, “three men in your life over a distance of 300 kilometres, three dead animals, three minor accidents or mishaps, although you aren’t necessarily directly involved in them, animals will be maimed, but the men and women will survive. However, it is clear that three animals will die before you meet the man of your life.”

I wearily try to point out from the depths of the sofa that I am a married woman and, by way of proof, feebly raise my right arm to stroke the simple wedding ring between my thumb and index. She pays no heed to this information, I’m not even sure she heard what I said.

“Things that no one will be expecting will happen, people will experience a lot of wetness, short-sightedness, greed, isolation, more wetness.”

“How do you mean wetness?”

“It’ll wet more than your ankles, that’s all I can say, impossible to know anything more than that today. I do, however, see a large marine mammal on dry land.”

She pauses briefly, there is a dead stillness in the room.

“There is a triple conception,” she continues, “one of them may be a trinity.”

What does the woman mean?

“My brother had test-tube triplets, they’re two years old now,” I awkwardly interject.

“I’m not talking about them,” the woman snaps, “I’m talking about three pregnant women, three babies on the way, three women who will give birth to babies over the coming months.”

“Well, there’s my friend Auður…”

Fortunately, she clearly has no interest in my input and shuts me up with a dismissive wave of the hand, as if I were an irksome teenager interrupting her private dialogue with some invisible being.

“And then there’s a big boy here, an adolescent, a narrow fjord, black sand, dwarf fireweed, the mouth of a river, seals nearby.”

Another one of her pauses.

“There’s a lottery prize here, money and a journey. I see a circular road, and I also see another ring that will fit on a finger, later. You’ll never be the same again, but it’s all done, you’ll be standing with the light in your arms.”

Those were her words, to the letter, “with the light in my arms”, whatever that was supposed to mean.

“To summarize it all,” she concludes in the manner of an experienced lecturer, “there is a journey here, money and love, even though you can expect some odd twists along the way. But I can’t see which of these three men it will be.”

When I finally stand up, I notice that she has placed all the cards on the table and arranged them in a strange pattern that is not unlike the one formed by the pile of wood outside, some kind of spider’s web with broken threads.

I suddenly feel the urge to ask:

“Did you make that wooden structure outside?”

She fixes her gaze on me, her pupils piercing through an ocean of shimmering blue:

“Keep an eye on the patterns, but don’t allow them to distort your vision, it takes a while to develop a good eye for patterns. Nevertheless, if I were in your shoes, I wouldn’t allow myself to be led into marshland in the fog. Remember that not everything is what it seems.”

As I’m about to hold out my hand to say goodbye, she suddenly embraces me and says:

“It wouldn’t be a bad idea to buy a lottery ticket.”

Her two adolescent sons offer to escort me back to the car, which I’ve forgotten where I parked, seemingly quite far away. Marching on either side of me, they look on with determined airs, as if they’d taken on a mission that had to be accomplished at all costs. We walk for what seems like a very long time, I even get the impression we’re travelling in circles and can’t remember ever coming this way. Then, just as I’m beginning to feel totally lost, the car materializes in front of me, close to a sea wall, in a place I don’t remember leaving it. It is unlocked, as usual, but all the papers are in their proper place, although I couldn’t vouch that every single sheet is in its pile. I see no point in checking on the goose in the boot. As I say goodbye, I realize for the first time that the brothers are twins and notice how they both always seem to shift their weight to their right legs as they walk. There is something odd in their gazes, pupils like black pins in an ocean of shimmering blue. As soon as I turn the key in the ignition and am about to wave them goodbye, I realize they’ve evaporated into thin air.

FIVE

He’s home. I linger on the frozen lawn before entering, looking in at the light of my own home, and shilly-shally by the redcurrant bush with the goose in my hands, wondering whether he can see it on me, whether he’s noticed. From here I can see him wandering from room to room for no apparent reason, shifting random objects and alternately flicking light switches on and off. I move from window to window around the illuminated home, as if it were a doll’s house with no façade, trying to piece together the fragments of my husband’s life.

Then he has suddenly emptied the washing machine and is standing in the bedroom with all the laundry in his arms, something he doesn’t normally do. He’s not much of a handyman either, but for some odd reason he seems to have changed the bulb under the porch and fixed a cupboard door in the kitchen. All of a sudden he is staring out the window into the darkness and I feel as if he were looking straight at me, scrutinizing me at length, as if he were pondering on how we might be connected or whether I’m going to come in or remain in the garden. He is naked above the waist, which must be quite chilly for him with that wet laundry in his arms, unless he is insulated by his body hair. When he bends over the bed, for a brief moment, I get the feeling there is someone lying on the bed, below my line of vision, and that he is about to lie down beside the person, but then he suddenly springs up again with my light blue damp panties in his hands, which he carefully stretches and presses in his big hands. He hangs them on the drying rack he has set up by the bed. I now see four pegs tugging at the extremities of my underwear. He may not spend much time at home and we may not talk much, but I have a good husband and I know I’m the one to blame, I never went to the shops.

SIX

He has obviously cleared up the kitchen and left a plate on the table for me, complete with knife, fork, glass and napkin. He has put on a shirt and tie, as if he were on his way out to an urgent meeting, and slips on the thick blue oven gloves, before stooping over the stove to pull out the lasagne.

He doesn’t sit with me, but tells me that he needs to talk, that we need to talk, that it’s vital, which is why he is pacing the chequered kitchen floor, in straight lines from the table to the refrigerator and then from the refrigerator to the stove, without any discernible purpose. His hands are burrowed in his pockets and he doesn’t look at me. I sink onto the kitchen stool, with my back upright, still wearing my scarf.

“This can’t go on.”

“What can’t go on?”

“I mean you’ve had your past abroad, which I’m not a part of. Initially, I found all the mystery that surrounds you exciting, but now it just gets on my nerves, I feel I can’t reach you properly, you’re so lost in your own world, always thinking about something other than me. It’s all right to hold some things to yourself, maybe fifteen per cent, but I get the strong feeling you’re holding on to seventy-five per cent. Living with you is like being stuck in a misty swamp. All I can do is grope forward, without ever knowing what’s going to come next. And what do I know about those nine years you spent abroad? You never talk about your life prior to me and therefore I don’t feel a part of it.”

I note that he refers to a swamp and mist, just like the medium had.

“You never asked.”

“I never get to know anything about you. You’re like a closed book.”

I feel nauseous.

When I was seven years old, I was sent on a coach to the countryside in the east on my own for the first time, with a picnic, a thirteen-hour drive along a road full of holes and dust, which the passengers ground between their teeth, in the coldness of the early June sun. The novelty that summer was that the bus companies had started to employ coach hostesses for the first time. There was a great demand for these jobs because the girls got to dress almost like air hostesses, in suits, nylon stockings and round hats fastened under their chins. The main function of the hostesses, apart from sitting prettily on a nicely upholstered cushion over the gearbox and chatting to the driver, was to distribute sick-bags to the passengers. When I had finished vomiting into the brown paper bag, I put up my hand the way I did in school whenever I needed to sharpen my pencil, and then the hostess came, sealed the bag and took it away. I saw the pedal on the floor right beside the entrance that she pressed with the tip of her high-heeled shoe to open the doors, which released a sound like the steam press in the laundry room, and how, with an elegant swing of the arm, she slowly cast the paper bag into an Icelandic ditch. The driver kept driving at fifty-five kilometres an hour and seemed relieved to be able to carry on chatting to the lady on the cushiononce the problem had been solved. Looking back on it, I think it more likely that the hostess was not wearing a hat but a scarf. I’d assumed they were a couple and engaged, she and the driver, but now realize she must have been two years out of the Commercial College whereas he had been driving the coach for decades.

He paces the floor again and loosens his new green tie, as if the stale air of the muggy late-summer heat were smothering him. He has also just had a haircut and he is wearing a shirt I’ve never seen before.

“Let’s take the way you dress, for example.”

“How do you mean?”

“The guys all tell me their wives buy their lingerie at Chez toi et moi.”

“I’m just me and you’re you and we are us, I’m not the guys’ wives and you’re not the guys.”

“That’s exactly what I mean, the way you twist everything, I can never talk to you.”

“Sorry.”

“Men are more attentive to these things than you think. We mightn’t say everything, but we think it.”

“I can well imagine.”

He looks offended.

“And there’s something else. All you’ve got to do is touch a light switch and the bulb blows. It’s not natural to be pushing a trolley-load of light bulbs every time I go shopping, minced meat and light bulbs, lamb and light bulbs, now I’m known as the man with the bulbs at the checkout.”

“Maybe we need to have the electricity checked.”

He paces the floor again.

“It’s as if you just didn’t want to grow up, behaving like a child, even though you’re thirty-three years old, doing your weird and careless things, taking short cuts over the gardens and fences of perfect strangers or clambering over their bushes. Whenever we’re invited somewhere, you enter through the back door or even the balcony, like you did that time at Sverrir’s; it would be excusable if you were at least drunk.”

“The balcony door opened onto the garden and half the guests were outside.”

“You’re always forgetting things, arriving the last at everything, you don’t wear a watch. And to top it all, you always seem to choose the longest routes everywhere.”

“I don’t get where you’re going with this.”

“Like that time you climbed halfway up that flagpole with the Icelandic flag in your arms…”

“Big deal, we were at a party, there was a knot in the rope, everyone looked helpless and the flag was drooping pathetically at half mast, like a bad omen for the asthma attack Sverrir was about to have later on, on the evening of his own birthday.”

“That’s the only time I was grateful that you were wearing trousers and not a skirt. The amount of times I’ve prayed to God to ask him to make you buy a skirt suit.”

“Wouldn’t it have been simpler to just ask me?”

“And would you have done that for me?”

“I’m not sure, I thought you were just happy to know that I was well.”

“There, you see?”

“I realize I can be impulsive sometimes.”

“Impulsive, yeah, you always have the right word for things.”

He rushes into the living room and returns with two volumes of the Icelandic dictionary in his arms, frantically skimming through the first tome.

“Words, words, words, exactly, your entire life revolves around the definition of words. Well, here you go, impulsive: abrupt, hasty, headlong and impetuous. Wouldn’t you like to tell me how they say it in Hungarian?”

His anger seems way out of proportion to the argument. Still sitting on the stool by the table, I notice a butterfly hovering close to the toaster, which is unusual for this time of the year. It is settling on the wall now, close to me, and perches there motionless, without flapping its silver wings. If you gently blow some warm air on it, it is clearly still alive. I swallow twice and remain silent.

“Those were my colleagues and Nína Lind was there too, she remembers it vividly. How do you suppose I felt?”

“Who’s Nína Lind?”

“Your hair is shorter than mine,” he says wearily, stroking his thick mane. He has taken one of his hands out of his pocket.

“And?”

“And then there are those friends of yours.”

“What about them?”

“Like that Auður girl, fun in some ways but a total crackpot. And with another fatherless child on the way.”

“That’s her business.”

“Yes and no, it’s been one year since we moved in here and we haven’t emptied all your boxes yet. I get the impression this home doesn’t really mean that much to you.”

“We need to find time to do that together.”

“You have a pretty weird idea of marriage, to say the least, you go out jogging in the middle of the night, dinner is never at the same time. Who else—apart from Sicilians—do you think would eat Wiener Schnitzel at eleven? Then when I get home on Tuesday you’ve cooked a four-course meal on a total whim, a Christmas dinner in October. And there’s me clambering over your runners in the hall holding a pizza with some awful topping in my arms, just to have something to eat. And who did the shopping again this evening? There’s no organization in your life, you can’t be sure of anything. It’s very difficult to live with these endless fluctuations and extremes.”

“You yourself often work nights or are abroad, you’ve only been at home for four nights this month.”

“I mean you speak eleven languages that you practically learnt in your sleep, if your mother is to be believed, and what do you do with your talents?”

“Use them in my work.”

“Having a child might have changed you, smoothed your edges a bit. But still, what kind of a mother would behave the way you do?”

It was bound to reach this point, the baby issue. But I’m a realist so I agree with him, I wasn’t made to be a mother, to bring up new humans, I haven’t the faintest clue about children, nor the skills required to rear them. The sight of a small child doesn’t trigger off a wave of soft maternal feelings in me. All I get is that sour smell, imagining their endless tantrums, swollen gums, wet bibs, sticky cheeks, red chins, the cold dribble on their chins. Anyway, it isn’t motherly warmth that men come looking for in me and they’re not particularly drawn to my breasts either. Besides, there are plenty of children in the world, our national highway is full of cars crammed with children, I should know. Three or four pre-school toddlers escaping from their young parents’ cars to raid every petrol station shop along the way. They need hot dogs and ice creams, after which they’re packed into the cars again, reeking of mustard, their faces plastered in chocolate. The parents look tired and don’t even talk to each other, don’t communicate, don’t notice the dwarf fireweed or glacier because of their carsick children. Your kids vanish into the bushes of camping sites, without ever giving you a chance to browse through a thesaurus in peace by the entrance to the tent, because you’re always on watch duty, I imagine. Some of our friends haven’t had a full night’s sleep for years and no longer make love, except for the very occasional little quickie. These are people who don’t even kiss any more, when they collect each other from work they just turn their heads and gaze out of the windows of their cars. I know that much, I’ve seen it. The relationships that survive having children are few and far between.

“You should at least organize yourself better, otherwise you’ll never be able to cope with having a child,” I hear him say to the broom cupboard.

If one really put one’s mind to it, it might be possible to develop the ability to read two pages of a book in a row. The child has grown suspiciously silent, the cookie is probably stuck in its throat, which is why you have to check on it every four lines, you’re always either putting a child into a sweater or pulling it out of one, shoving Barbie into her stockings and high heels, groping for your keys outside the front door with a sleeping child in your arms. No, it’s not my style. I try to regurgitate an entire paragraph from a manuscript I once proof-read:

“One of the things that characterizes a bad relationship is when people start feeling an obligation to have a child together.”

I have to confess that’s something I read somewhere, because we can’t experience everything in the first person. Nevertheless, I throw in an extra bit of my own.

“But maybe we could adopt, in a few years’ time, a girl from China, for example, there are millions of surplus baby girls in China.”

“That’s exactly it, when you’re not talking like a self-help manual, you behave as if you were living in a novel, as if you weren’t even speaking for yourself, as if you weren’t there.”

“At least I’m not Anna Karenina in a railway station.”

“What’s that supposed to mean?”

“I don’t necessarily absorb the content of all the text that I proof-read, you know, nor do I emulate it.”

“But just remember this: not all men are bright and chirpy in the morning, and you can’t expect them to appreciate the nuances of linguistics over their morning porridge.”

He has straightened his back and randomly presses his thumb against the window pane, just beside one of the butterfly’s wings.

“What do you mean?”

“It isn’t always easy to figure out what you’re on about. Other people just chat when the bread pops out of the toaster. Maybe, for example, they say things like: the toast is ready, would you like me to pass it to you? Would you like jam or cheese? They talk about cosy, homely things like washing powder, for example, things that mean something in a relationship. Have you ever asked yourself if I might like to talk about washing powder? Somehow you’re never willing to talk about washing powder. Last time you washed my shirts it was with your red underwear. It’s true that I was the one who gave it to you, but I don’t remember ever seeing you wear it. And that’s not the only thing.”

“No?”

“No, I just want to let you know that I’ve spoken to a marriage counsellor and he agrees with me.”

“About what?”

“About you. He had a similar experience. With his first wife.”

As I’m calmly sitting there on the stool and sip on the glass of water, I realize that he is now about to say something that I’ve somehow sensed he would say, something that has crossed my mind before. And the thought is accompanied by a feeling that I’ve also experienced before, although I cannot for the moment remember where it will lead, to something good or bad. I know what he’s going to say next.

“And then there’s Nína Lind.”

“Who’s she?”

“She works at the office, handles the switchboard and takes care of the photocopying for now. She’s planning on studying law.”

His voice vanishes into the collar of his shirt. Some hairs protrude through his buttonholes.

“She’s actually expecting… a baby.”

“And?”

“Yeah, and so am I, with her.”

“Isn’t she the one you said was coming on to all the guys at that Christmas punch party in your office last year?”

“Not any more. You should also know, with all your vaster knowledge,” he says with a touch of sarcasm, “that when a man is unjustifiably critical of someone, it’s often to conceal a secret admiration. Men quite like women to have a bit of experience. I have to confess I’ve sometimes wished you had vaster experience in that area yourself.”

I note that he’s using the word vaster for the second time. If I were proof-reading this, I would instinctively cross out the second occurrence, without necessarily pondering too much on the substance of the text.

“You don’t even know how to flirt, don’t even notice when men are looking at you. It’s not much fun when the signal that a man’s wife gives out to the world is that she is completely indifferent to the attention the world gives her.”

I can’t control myself and note that this is the second time he has called upon the world as his witness in a single sentence.

“Besides, she’s changed, pregnancy changes a woman.”

“When is the baby due?”

He hawks twice.

“In about eight weeks’ time.”

“Isn’t that a rather short pregnancy, like a guinea pig?”

“This is something that has evolved between us over a period of time, not just an accident. I just want you to know that this wasn’t a decision on the spur of the moment, or just a whim, even if you think it is.”

His face has turned crimson, with his hands dug deep into his pockets.

“How did you get to know each other?”

“In the photocopy room or around there.”

“When?”

“You could say the relationship turned serious sometime after the Christmas party.”

He fumbles around the refrigerator, takes out a carton of milk and pours himself a full glass. I didn’t know he drank milk.

“Christ, how old is this milk? It’s the 25th of October today and this is from September.”

“What does she have that I don’t have?”

“It’s not necessarily that she has something you don’t have, although in many ways she’s more feminine, has breasts and stuff.”

“Don’t I have breasts?”

“It’s not that you don’t have breasts, but she’d never been to Copenhagen, for example, I had the feeling I could teach her something.”

“Did she go to Copenhagen with you the other day?”

“Yes, she did, as it happens. Like I said, it’s been evolving.”

“And Boston too?”

“She was visiting a cousin there as well.”

He has started to nurse the plant on the window sill, and fetches a glass to water it, and then massages the soil around the stem with his fingers. I’ve never seen him care so much for a plant.

“Do you love her?”

He gives himself plenty of time to readjust the plant and wash his hands in the kitchen sink, after his labour in the soil, before answering.

“Yeah. She says she loves me and can’t live without me.”

In retrospect there had been a number of signs in the air. He had suddenly started to plant clues in various parts of the apartment and wrote “I will never forget you” on the back of an unpaid electricity bill, knowing that I was the only person in the house who ever does chores like paying bills. I actually didn’t notice the inscription until I got to the bank and the cashier blushed and double-stamped the bill. And then there were the home-made crosswords he left by the phone: love, nine down, longing six across, coward seven down. Affection, desire and chicken.

“I want you to know I’m very disappointed things didn’t work out between us,” he says.

I’ve shovelled down two mouthfuls of the spinach lasagne and am preparing to stab the third morsel with my fork. Once I’ve swallowed it, I adjust my garter-stitch scarf, wrapping it around my throat.

“Thanks for the dinner. When are you leaving?”

“Nína and I are looking for an apartment and we’re going to see one tomorrow. In the meanwhile I’ll stay at Mum’s.”

In light of all the things that can happen in a day, coincidences clearly have a tendency to come in bunches. Two men have given me my marching orders today, dumped me. I feel like a prisoner who has helped a cellmate escape by lending him my back. But I’m still capable of surprising myself. I can do better.

“I was going to cook some goose this weekend.”

“Goose, where did you get goose?”

“In Mum’s freezer.”

“Unfortunately I’m really busy.”

“Come on, everyone has to eat, it’s not as if I was asking you to tidy up the garage or something.”

It would be OK to eat together. We can make it our last supper, our Christmas feast.

He is unable to resist.

“I’ll come for the dinner at any rate, no point in letting a goose go to waste.”