Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

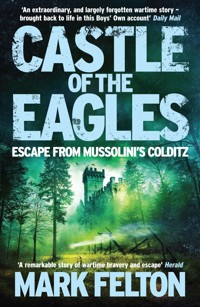

'Keeps up the suspense to the end.' The Times Literary Supplement 'An extraordinary, and largely forgotten wartime story -- brought back to life in this Boys' Own account.' The Daily Mail High in the Tuscan hills above Florence, an elaborate medieval castle, converted to a POW camp on Mussolini's personal orders, holds one of the most illustrious groups of prisoners in the history of warfare. The dozen or so British and Commonwealth senior officers includes three knights of the realm and two VCs. The youngest of them is 48, the oldest 63. One is missing a hand and an eye. Another suffers with a gammy hip. Against insuperable odds, these extraordinary middle-aged POWs plan a series of daring escape attempts, culminating in a complex tunnel deep beneath the castle. One rainswept night in March 1943, six men will burst from the earth beyond the castle's curtain wall and slip away. By assorted means, the three Brits, two New Zealanders and a half-Belgian aristocrat will attempt to make it to neutral Switzerland, over 200 miles away.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 484

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CASTLE OF THE EAGLES

Also by Mark Felton

Zero Night: The Untold Story of World War Two’s Most Daring Great Escape

The Sea Devils: Operation Struggle and the Last Great Raid of World War Two

CASTLE OF THE EAGLES

ESCAPE FROM MUSSOLINI’S COLDITZ

MARK FELTON

Published in the UK in 2017 by Icon Books Ltd, Omnibus Business Centre, 39–41 North Road, London N7 9DP email: [email protected]

Sold in the UK, Europe and Asia by Faber & Faber Ltd, Bloomsbury House, 74–77 Great Russell Street, London WC1B 3DA or their agents

Distributed in the UK, Europe and Asia by Grantham Book Services, Trent Road, Grantham NG31 7XQ

Distributed in Australia and New Zealand by Allen & Unwin Pty Ltd, PO Box 8500, 83 Alexander Street, Crows Nest, NSW 2065

Distributed in South Africa by Jonathan Ball, Office B4, The District, 41 Sir Lowry Road, Woodstock 7925

Distributed in India by Penguin Books India, 7th Floor, Infinity Tower – C, DLF Cyber City, Gurgaon 122002, Haryana

ISBN: 978-178578-118-6 (hardback) ISBN: 978-178578-219-0 (paperback)

Text copyright © 2017 Mark Felton

The author has asserted his moral rights.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any means, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Typeset in Janson Text by Marie Doherty

Printed and bound in the UK by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

To Fang Fang with love

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Mark Felton has written eighteen books on World War Two including Zero Night (‘the story of the greatest escape of World War II has been told for the first time’ – Daily Mail) and The Sea Devils (‘A thrilling page-turner … it will leave your fingernails significantly shorter’ – History of War). His Japan’s Gestapo was named ‘Best Book of 2009’ by The Japan Times. He also writes regularly for publications including Military History Monthly and World War II. After a decade spent working in Shanghai, he now lives in Norwich.

Visit www.markfelton.co.uk

Contents

Prologue

1 The Prize Prisoner

2 A Gift of Goggles

3 Mazawattee’s Mad House

4 Men of Honour

5 Advance Party

6 The Travelling Menagerie

7 The Eagles’ Nest

8 Trial and Error

9 Going Underground

10 Six Seconds

11 The Ghost Goes West

12 Under the Dome

13 Through the Night of Doubt and Sorrow

14 The Pilgrim Band

15 Elevenses

16 Boy Scouting

17 Mickey Blows the Gaff

18 Night Crossing

Epilogue

Colour Plates

Acknowledgements

Bibliography

Notes

A NOTE ON THE TEXT

Most of the dialogue sequences in this book come from the veterans themselves, from written sources, diaries or spoken interviews. I have at times changed the tense to make it more immediate. Occasionally, where only basic descriptions of what happened exist, I have recreated small sections of dialogue, attempting to remain true to the characters and their manners of speech.

Prologue

The short, wiry man with the grey military moustache, known to everyone simply as ‘Dick’, sat slightly uncomfortably between two companions on a stone bench that had been warmed by the bright Tuscan sun. He wore a plain grey civilian suit and on his back was a bulky homemade rucksack that looked fit to burst. Stuck in the waistband of his trousers was a peculiar wedge-shaped block of wood with a metal hook protruding from its narrowest side. The terrace where the three men sat was pleasant, stretching along the western side of the castle’s central keep, and actually consisted of a lower and upper terrace enclosed by an eight-foot-high, thick stone perimeter wall, the top of which was crenellated with medieval battlements. The prisoners used the lower terrace for exercise while the guards watched them easily from the upper terrace, any danger of fraternising neatly eliminated.1

The castle, built of grey stone, sat imperiously atop a high rocky hill near the village of Fiesole, five miles from the Renaissance splendours of Florence. It was a gloomy Neo-Gothic reconstructed medieval fortress, the slopes of its lofty perch planted with cypress, pines and shrubs.

Beyond the huge wall was a sheer drop of some 30 feet to the solid bedrock below, upon which the great castle had been constructed many centuries before. Two tall battlemented towers rose up at the castle’s northern end, overlooking the main gate and road down to the nearby village, a smattering of tiled roofs and little fields huddled at the foot of the hill. The views from the Castle’s terrace were stunning – rolling green hills that stretched away to Florence. On a good day one could see the golden dome of the Basilica di Santa Maria del Fiore shimmering in the sun like a precious jewel.

Dick’s heart was racing. He was waiting for a window of opportunity that would be measured in just a handful of seconds. That was all the time he had to make his daring bid for freedom. It was risky to attempt such a thing in broad daylight, but he had no choice. At night Dick and his fellow prisoners were confined to their rooms in another part of the castle and denied access to the terrace.

Tuscany was hot and sultry in late July 1942, and Dick sweated inside his suit as he waited for the signal to go. His keen blue eyes carefully watched as his comrades moved into their positions to assist his escape.

Suddenly the signal was given. Dick didn’t hesitate. He stood up on the bench, facing the wall, raised his arms above his head and stiffened his legs. His comrades on either side took hold of his legs and, as they had practised so many times before, launched Dick skywards. Dick stretched his arms up until his fingertips found the bottom of the guards’ walkway and then he pulled with all his might, his comrades pushing on the soles of his feet until he was out of reach. With a supreme effort Dick fought to gain the platform, his short legs pedalling in the air as his arms took the strain. With panic rising like a wave inside of him, 53-year-old Lieutenant-General Sir Richard O’Connor, the hero who had defeated the Italians in Africa and taken 130,000 prisoners into the bargain, gritted his teeth and pulled for all he was worth. One of the unlikeliest escapers of the Second World War was about to try one of the most daring escapes in the history of war.

CHAPTER 1

___________________

The Prize Prisoner

‘After nine months as a member of his staff, when we left England I admired and respected Air Marshal Boyd. After two and a half years of prison life with him, living in the same house, often in the same room, I admired and respected him a hundred times more. I knew him then to be a great and simple man.’

Flight Lieutenant John Leeming

John Leeming cursed loudly as his shoulder connected painfully with one of the Wellington bomber’s internal struts, his stomach lurching as the stricken plane pitched and rolled alarmingly through the air as it headed for the earth. The wind screamed like a typhoon through a large and jagged hole in the Wellington’s floor, one of several caused by cannon shells from the swarm of Italian fighters that had suddenly pounced on them without warning.1 Leeming kicked at a heavy grey steel strongbox with one of his long legs, edging it towards the lip of the hole until, with a final push of his boot, the box flew out of the aircraft, plummeting towards the Mediterranean far below. One more box remained, and Leeming, dressed in his blue RAF officer’s uniform with pilot’s wings above the left breast pocket, his legs aching from his awkward position on the plane’s floor, began to kick at it wildly until it followed the other boxes out through the hole. Then Leeming lay on the floor for a few seconds, listening to the roar of the dying engines as the wind blew everything that wasn’t secured around the Wellington’s interior like a mini tornado. I’ve just thrown away £250,000, thought Leeming, shaking his head in silent disbelief. ‘A quarter of a million of pounds sent to the bottom of the sea!’ he muttered aloud. In Leeming’s opinion, the war had suddenly taken a dramatically strange turn for the worse.

‘Brace for impact!’ came Squadron Leader Norman Samuels’ frantic yell from the cockpit. ‘She’s going in hard!’ Leeming was instantly jerked out of his private reverie, rolling on to his stomach and grabbing hold of anything solid-looking that would support him. He glanced behind him and saw his boss, Air Marshal Owen Tudor Boyd, ‘a short, broad-chested, and powerfully built’2 man with short greying hair and a neat moustache, doing likewise, his normally genial face set with a determined grimace. Boyd caught his eye and mouthed something, but Leeming couldn’t hear what it was above the racket of the whining, guttering engines and the ceaseless wind. Leeming glanced back at the hole through which he had just deposited the cash boxes. The azure of the sea had been replaced by green rolling hills and fields. ‘Sicily,’ muttered Leeming to himself. The Wellington was now very low. Leeming closed his eyes and awaited the end.

*

A strange quietness followed the terrific violence of the crash landing. Leeming lay on his side in the broken fuselage, his hands still grimly gripping a spar. The air was dusty and there was a ticking noise coming from one of the engines as it cooled. Then Air Marshal Boyd, Leeming and the four crewmen began to stir, groaning and occasionally crying out in pain from their injuries. Leeming dragged himself out of the fuselage with the others. His arm hurt like hell.

Once outside, Leeming surveyed the Wellington. The plane was a complete wreck: one of its huge wings had broken off, its nose was smashed in, and the big propeller blades had been bent back on themselves by the force of the impact. For several hundred feet behind the Wellington the Sicilian landscape had been gouged and churned up by the crash landing. Leeming narrowed his eyes against the glare of the sun, which was warm on his smoke-blackened face. Boyd slowly stood and walked, slightly unsteadily, around to the cockpit where he began fumbling in his pockets, pulling out some papers and his cigarette lighter. Leeming soon realised that the Air Marshal was trying to set fire to the plane. It was a vital task, considering what Boyd had been carrying aboard among his personal kit. His private papers would comprise an intelligence treasure trove if they were to fall into the hands of the enemy. They, along with the plane, had to be thoroughly destroyed before the Italians arrived to investigate and take the Britons prisoner.

Leeming reflected on the journey that had landed him unexpectedly in the hands of the enemy. They had taken off from RAF Stradishall near Haverhill in Suffolk on 19 November 1940 bound for Cairo via the airfield at Luqa in Malta. Once in Egypt, the 51-year-old Boyd was to assume deputy command of Allied air forces under Air Chief Marshal Longmore.3 The appointment of the energetic Boyd to the Middle East came at a time when Britain was struggling to maintain its position in Egypt against a huge Italian assault.

Benito Mussolini had entered Italy into the war on Germany’s side in late June 1940, after witnessing Hitler’s triumphs in Poland and against the Western Allies in France and the Low Countries. Il Duce undoubtedly thought that Italy might be able to snatch a few of the victory laurels for herself on the back of Germany’s defeat of France and the ejection of the British from the Continent. But the Italian entry into the war was particularly worrisome for Britain in the Mediterranean, a traditional bastion of British power. The large and powerful Italian fleet and the massive Italian army in Libya posed serious threats to the British Empire’s lifeline, the Suez Canal, as well as to British bases at Malta and Gibraltar. Already seriously run-down as the best equipment was siphoned off for the defence of Britain against a possible German invasion, the small British garrison in Egypt was vulnerable and difficult to supply. Mussolini had ordered the invasion of Egypt in early August 1940, and by 16 September the Italian 10th Army had occupied and dug in around the Egyptian town of Sidi Barrani. Outnumbered ten to one, the small British force under General Sir Claude Auchinleck had begun planning for Operation Compass, a series of large-scale raids against the Italian fortresses that would be led by a plucky and aggressive general named Richard O’Connor. Owen Boyd was being sent to Egypt to attempt to revitalise and reorganise the RAF’s response to the Italian threat. Boyd seemed the ideal choice – a pugnacious First World War decorated flyer whose last post had been leading RAF Balloon Command, providing vital barrage balloon cover for Britain’s cities.

But now, eleven hours after leaving England, Air Marshal Boyd’s plane was a battered wreck lying in a Sicilian field. After they had dodged German flak near Paris, Wellington T-2873 from 214 Middle East Flight had headed out over a wet and stormy Mediterranean towards Egypt, with a scheduled refuelling stop at Malta.4 But an apparent navigational error and consequent fuel shortage had brought the Wellington too close to the island of Sicily where it was immediately pounced upon by alert Italian fighters and forced down.5 Questions would be asked as to why Boyd’s plane had been sent unescorted to the Middle East by such an obviously dangerous route, especially as he was one of the few senior officers that were privy to the secrets of Bletchley Park and the ‘Ultra’ intelligence emanating from cracking the German Enigma code.6 It was for this reason that Boyd, still shaken up from the crash landing, struggled to burn the aircraft and his private papers that had been carried aboard.

The boxes full of banknotes that Leeming had kicked overboard into the sea had been loaded under guard in England. They had been destined for the British headquarters in Cairo as well, vital operating funds for various hush-hush sections that conducted ‘butcher and bolt’ operations behind enemy lines. Once the Wellington had been hit, Boyd had pointed at the small pile of grey boxes and yelled at Leeming: ‘Get rid of it, John! We’re going down in enemy territory!’7 Shortly afterwards Leeming, his heart heavy at the sacrifice, had kicked out the quarter of a million pounds, ironically enough money in 1940 to buy a replacement Wellington three-and-a-half times over.8

It had only been because of the direct intervention of Prime Minister Winston Churchill that Boyd had been on the plane. Air Chief Marshal Longmore had requested a different officer be appointed his deputy, Air Vice-Marshal Arthur Tedder, but the Prime Minister had rejected Tedder and approved Boyd’s promotion instead.9 With Boyd having been taken prisoner, Tedder would now assume Boyd’s post anyway.

*

Boyd looked up from his frantic job of setting fire to the front of the plane and spotted movement. A motley collection of Sicilian peasants, dressed in their traditionally colourful open-necked shirts, broad waist sashes and trousers worn with puttees up to their knees, were gingerly approaching the crash scene, armed with wood axes. They had been cutting down trees near the village of Comiso. ‘Stop them, John,’ shouted Boyd at Leeming. Leeming turned and stared at the peasants. With their axes slung over their shoulders, moustachioed faces and old-fashioned clothes, they looked like the kinds of rogues who had been at Blackbeard’s side. Leeming swallowed hard and stood rooted to the spot. Boyd’s booming and irritated voice repeated his order. Is this how it ends for me, thought Leeming gloomily, I survive a plane crash only to be murdered by Sicilian cut-throats?

Focusing his mind, Leeming followed his friend’s order and began walking towards the Sicilian peasants. He touched the .38 calibre Webley revolver that he wore in a holster around his waist, but then thought better of it. He didn’t relish waving a gun in the face of these well-armed locals, particularly a gun that only held six shots when there were fifteen armed Sicilians. Instead, he reached into his shirt pocket and pulled out a battered packet of Woodbines and a stub of pencil and started to draw a Union Jack.10 Holding up his artwork before the Sicilians, he noticed how the sun glinted off the sharp axe blades that were slung over their shoulders. The peasants soon gathered around him in an excited, chattering mass as they debated loudly what to do.11 Suddenly, over Leeming’s shoulder the cockpit of the shattered Wellington burst into flames with a loud ‘whoomph’, startling the Sicilians who began running around, yelling and shrieking excitedly. They were clearly worried about explosions, probably thinking that the Wellington was equipped with a full bomb load. Leeming took the opportunity to retreat to where Boyd, Squadron Leader Samuels, Flight Lieutenant Payn, Pilot Officer Watson and Sergeant Wynn had gathered near the aircraft’s tail.12 Thick black smoke poured from the front of the plane, blotting out the harsh sun, as the flames devoured the Wellington’s interior. Boyd smiled at his handiwork.

Leeming, determined to salvage his personal kit before the rest of the plane was engulfed, climbed back inside the fuselage. Grabbing the kit, he was suddenly lifted out of the aircraft as if thrown by a huge hand, landing in a winded pile on the grass. Squadron Leader Samuels had managed to arm a special explosive device designed to destroy the plane’s sensitive equipment shortly before they had crashed, and this had detonated just as Leeming grabbed his kit. Leeming had had enough. He lay on his back on the grass attempting to recover his composure, the pain in his arm bothering him, listening to Boyd attempting to coax the Sicilians back over in a loud, impatient voice, telling them in English that there were no bombs on board. His efforts were suddenly undermined when the flames reached the oxygen cylinders carried aboard the Wellington, which promptly exploded, spraying shrapnel through the air. Leeming, Boyd and the others jumped to their feet and ran after the Sicilians, anxious to put as much distance as possible between themselves and the rapidly disintegrating plane.13

*

It had already been a long road for Leeming, at 45 years old one of the oldest Flight Lieutenants in the RAF. Born in Chorlton, Lancashire in 1895, Leeming had demonstrated an early talent for writing, publishing his first article at the age of thirteen. He was later to write many bestselling books, some indulging his fascination with aviation. While at school he witnessed some of the early efforts at powered flight and quickly became hooked. In 1910, aged fifteen, Leeming had built his first glider, and he continued to build and fly gliders throughout the 1920s. Moving on to powered aircraft, Leeming had achieved lasting fame in 1928 when he and Avro’s chief test pilot Bert Hinkler became the first people to land an aircraft on a mountain in Britain. They selected 3,117-foot-high Helvellyn in the Lake District for their stunt, managing to set down and take off again in an Avro 585 biplane. Leeming had founded Northern Air Lines in 1928, and he was instrumental in finding a new airport site for Manchester at Ringway.

In the early 1930s Leeming had branched out into horticulture, building a stunning garden at Bowden, writing bestselling gardening books and creating the character ‘Claudius the Bee’ for the Manchester Evening News. Walt Disney bought the film rights. With the onset of war in 1939 Leeming had been commissioned into the RAF and appointed as aide-de-camp to Air Marshal Boyd. Though separated by a considerable difference in rank, Leeming at 45 and Boyd at 51 were close in age and united by their fascination with flying, going back to childhood for both men. They were to become close friends and comrades during the coming years of adversity.

*

‘You know,’ declared Air Marshal Boyd to Leeming, Samuels and the other RAF crewmen who were sitting inside a tiny house before a large audience of excited villagers, ‘all this is highly irregular.’14 Boyd, who was seated on the only chair inside the hovel, was referring to the fact that the Sicilian peasants had yet to disarm them. The Air Marshal was a stickler for the rules and regulations, and dealing with civilians, particularly foreign civilians, was wearing what remained of his patience thinner. Each Briton still wore his service revolver on a webbing gun belt around his waist. Boyd, noted Leeming, sat in the centre of the room ‘like some medieval monarch holding Court, we grouped like courtiers around him, the crowd of chattering villagers facing us.’15 Boyd, stern-faced and clearly not impressed by the situation, decided upon a ‘proper’ gesture. It was inconceivable that no one had yet demanded that they surrender. ‘We’d better hand over our revolvers,’ he stated, resolutely making up his mind.

Boyd slowly rose from his chair and reached into his holster, pulling out his pistol, Leeming and the Wellington’s crew following suit. But if Boyd had expected a formal surrender ceremony he was soon disabused of the notion as a peasant instantly snatched the proffered sidearm from Boyd’s outstretched hand, while other Sicilians crowded forward in a noisy tumult. The British revolver was worth a considerable sum of money to the impoverished locals, who soon descended into a pushing and shoving mob who competed loudly and increasingly violently for ownership.

Boyd, not content to see his surrender gesture reduced to a farce, acted swiftly to restore order. He suddenly launched himself into the crowd, his squat, broad-shouldered frame bulling through the riotous locals and roaring at the peasant who had taken his pistol: ‘Give it to me!’ Though the Air Marshal was rather diminutive, the peasants reacted to Boyd’s force of personality, drawing back from the red-faced and shouting foreigner in fear. It was a magnificent display of sheer bravado on Boyd’s part, but entirely in keeping with his strong character. ‘Give me that!’ shouted Boyd, snatching the pistol from the peasant who’d originally pinched it. He broke it open and emptied the shells into his other hand before snapping the pistol shut and handing it back. ‘Now you’ll be safe,’ Boyd explained to the confused peasant, enunciating each word in the loud manner many English use when addressing foreigners. ‘Silly devils! You might have shot yourselves!’16

Shortly afterwards a unit from the Royal Italian Navy arrived from a nearby base and formally took Boyd and his companions prisoner. This time the ‘surrender ceremony’ was a good deal more dignified, and Boyd was satisfied. The Britons were conveyed by car to the Italians’ base where they were given an enormous meal before being taken on to the town of Catania, on Sicily’s east coast.17 Their journey into an uncertain captivity had commenced.

*

Darkness had fallen by the time the car carrying Boyd and Leeming arrived at Catania. Their fellow captives were being separately conveyed to another camp.

‘Dear me,’ muttered Boyd under his breath as he looked out the car window. ‘The place is lit up like a bally Christmas tree.’ Both RAF officers were struck by the ineffective local blackout, with shops still brightly lit and even streetlamps on in places. Boyd did a fair amount of tut-tutting under his breath as they drove by, making comparisons with the British blackout. Eyebrows were raised further when Boyd and Leeming were summoned to see 49-year-old Major-General Ettore Lodi, the handsome and rather serious officer commanding the 3rd Air Division ‘Centauro’ and the senior Italian on Sicily.18 Lodi was deeply proud of his ‘blackout’, and took pains to point out to Air Marshal Boyd that many of the city’s street lamps were extinguished. Turning to Boyd, through an interpreter he asked for his professional opinion of his efforts. The Air Marshal, ‘one of those honest people who say what they really think’,19 told him.

A red-faced General Lodi and his ADC personally showed the exhausted RAF officers to their quarters. Each man was given a bedroom, sharing a spartan bathroom. After being left alone for a while, the Britons heard someone moving around outside the door to Boyd’s room. Intrigued, Boyd and Leeming cracked the door slightly and peeked out. Standing in the corridor was a bored-looking Italian soldier armed with a rifle and fixed bayonet. Using sign language, Boyd managed to ascertain that the sentry was to remain on duty outside the door all night. This news seemed to strike Boyd as an affront.

‘The poor chap won’t be relieved all night, John,’ said Boyd, his brow deeply furrowed by this further evidence of Italian military inadequacy. ‘It’s just not on, John, not on at all.’

During his previous commands, Boyd had built up a sterling reputation as an officer that genuinely cared for the welfare of those serving under him. Typically of the man, Boyd now extended this solicitude to his enemy.

‘The poor devil can’t stand there all night,’20 he said, still baffled by the incompetence of it all. Suddenly he made up his mind and strode across his room, snatching up one of the warped wooden chairs that they had been issued with and handed it to the sentry, indicating that he should sit. The astonished sentry, his eyes round with amazement, took the chair from Boyd.

‘Grazie, grazie,’ said the sentry over and over, making little bowing movements before finally sitting down.

‘Not at all, my dear chap,’ said Boyd, grinning, as he closed the door.

‘That Lodi devil ought to be relieved of his command, John,’ said Boyd once the door was shut. ‘Can you imagine a British officer treating his chaps in such a fashion?’ Leeming admitted that he couldn’t and sat on his bed while the Air Marshal pottered about the room muttering about ‘incompetence’ and ‘slovenliness’ until he finished hanging up his uniform and retired to bed.

After a little while they heard a key being gently turned in the door and for the first time their situation sank in – they were prisoners of war. ‘There seemed something grim and final about the turning of the key,’21 wrote Leeming. For a long time he stared into the darkness, unable to sleep and more than a little apprehensive about what the morrow would bring.

*

‘My God! I’m slipping, John!’ the voice from outside the window said in a fierce whisper. It was the dead of night and Air Marshal Boyd was clinging for dear life to a rickety drainpipe that ran outside his bedroom window down to a drain at the foot of the building. Leeming leaned out of the open window and grasped his boss by both arms. ‘I’ll pull you in, sir,’ he gasped, attempting to take the strain. But it was easier said than done. For a few seconds it was touch and go, as Leeming thought that he would have to make a decision between dropping Boyd the twenty feet to the stone courtyard below or risking being dragged out of the window by the weight of the Air Marshal’s dangling frame. But, after much struggling and cursing, Leeming managed to pull Boyd up to the ledge, where the exhausted Air Marshal clambered back inside, the beam of a sentry’s torch settling momentarily upon Boyd’s struggling legs and posterior as they disappeared over the window ledge. Seconds later the bedroom door burst open and several Italian soldiers rushed over to subdue the two struggling RAF officers. This first attempted escape from the Italian HQ at Catania, where Boyd and Leeming were imprisoned for several weeks, had been precipitated by Leeming’s pre-war reading of thrillers featuring dashing cat burglars who shinned like cats up drainpipes to crack safes and steal jewels. ‘What we failed to realise was that at our age climbing down a drainpipe was a precarious and difficult feat,’22 wrote Leeming later with commendable understatement. Only after this false start did Boyd realise that they had gone about the thing the wrong way. ‘Further experience would have suggested the use of sheets,’23 he would comment, without a trace of irony.

Leeming was constantly amazed by his boss’s ability to soldier on. Boyd’s career had effectively come to an end when his plane had been forced down in Sicily. If he had reached Egypt he could have expected eventually to have taken full command of the RAF in the Middle East, to have been promoted to Air Chief Marshal and in all likelihood to have received a knighthood. As it was, those honours and more besides were to go to the man that Churchill had originally blocked from the post, Arthur Tedder. While Boyd would languish in captivity, Tedder would rise to fame, eventually becoming Deputy Supreme Allied Commander under General Dwight D. Eisenhower.24

The fortunes of war were further compounded for Boyd when he received a letter from London while a prisoner at Catania, informing him that as he had only held the rank of Air Marshal for seventeen days before capture, and as 21 days were required before confirmation of promotion, he was hereby demoted to Air Vice-Marshal and his pay was concomitantly reduced. But Leeming never heard Boyd utter a single word of complaint. Instead, the tough old dog started plotting his next escape. Considering what he had lost, it is small wonder that Boyd was so determined to get back home and back into some position of influence over the course of the war.

The drainpipe episode earned Leeming and Boyd a transfer to Rome, with the crew of their shot-down Wellington joining them. The headquarters at Catania was never designed to hold prisoners of war, and Boyd had by now learned that the Italian press had dubbed him ‘Italy’s Prize Prisoner’.25 Clearly, Mussolini intended that his prize should be secured somewhere more appropriate – a location where shinning down drainpipes in the dead of night might be less of an option.

Boyd and Leeming finally left Catania in a battered military bus provided by General Lodi, who was thrilled to see the back of them, bound for the port of Messina, their suitcases crammed full of enough Italian toilet paper to last them for at least a year: almost as soon as Boyd had arrived at the Catania HQ, he had started stealing the toilet paper. Leeming was initially nonplussed by his boss’s new pastime.

‘Damned primitive,’ said Boyd, pointing at their joint bathroom. ‘And this is an HQ, John. Imagine what a prison camp is going to be like. No, we need to prepare for every eventuality and err on the side of caution.’ So caution dictated that the two of them pinch every roll of lavatory paper that the Italians provided. Leeming later wrote that the Italians must have been considerably baffled by this strange behaviour. Each morning when they inspected the prisoners’ toilet they discovered an empty lavatory roll hanging on its spool, and duly replaced the paper. Each morning, an entire fresh roll was gone. British intestinal habits must have quietly amazed and fascinated their captors, Leeming would surmise.

Whether Boyd and Leeming would need all that pilfered toilet paper now that they had departed from Lodi’s HQ, only time would tell. For now, their ultimate destination remained top secret.

CHAPTER 2

___________________

A Gift of Goggles

‘The Italians were hatefully full of themselves, for they had had a bumper week with a galaxy of generals in the bag…’

Major-General Adrian Carton de Wiart

On the evening of 6 April 1941 two cars sped across the Western Desert, headed for Tmimi, Libya. The first, a Lincoln Zephyr, carried the past and present commanders of the Western Desert Force, Lieutenant-Generals Sir Richard O’Connor and Sir Philip Neame, along with another seasoned desert campaigner, Brigadier John Combe, and a driver. Behind them, a Ford Mercury held Neame and O’Connor’s batmen, Neame’s aide-de-camp Lieutenant the Earl of Ranfurly, and a driver.1

The desert campaign that had been going so well for the Allies at the beginning of the year had suffered an alarming reversal of fortunes since the Italian forces had been joined by Germany’s Afrika Korps. Now, with their headquarters at Marawa in danger of being overrun by the rapidly advancing Germans, Neame, O’Connor, Combe and their aides had taken the decision to evacuate and withdraw to Tmimi.

Dick O’Connor had arrived in Libya just days before, Sir Archibald Wavell, British commander-in-chief in the Middle East, having decided that he needed to call upon the talents of his finest desert general once again. It was not that Wavell lacked confidence in the present commander of the Western Desert Force, the indomitable and brilliant Neame, it was just that Neame lacked desert experience while O’Connor had virtually written the book on North African campaigning.

O’Connor had first joined the army in 1909, and had returned from the First World War with a Military Cross and the Distinguished Service Order and Bar, indicating the second award of a decoration that ranked only one place below that of the Victoria Cross. He had gone on to command a brigade along the fiercely dangerous Northwest Frontier of India in 1936 and faced down the Arab Revolt in Jerusalem in 1940. But it was his performance in Africa that had established his reputation. With his short grey hair and neatly trimmed white moustache, ‘General Dick’, as his contemporaries fondly knew him, had taken command of the Western Desert Force with the ominous task of trying to stop the massive Italian invasion of Egypt. With a force much smaller than his opponent, O’Connor had done just that, launching Operation Compass on 9 December 1940. In two days the British had smashed the Italians at Sidi Barrani. O’Connor had then pushed the Italians back into Libya.

In January 1941, he had reorganised Western Desert Force then struck the Italian fortress of Bardia. It fell after two days of fighting. On 21 January O’Connor’s forces had captured the strategically vital port of Tobruk. In February Beda Fomm had fallen, O’Connor capturing 20,000 Italians for the loss of just nine British and Australians killed and fifteen wounded. In a stunning run of victories over ten weeks, O’Connor’s force had captured 130,000 Italian and Libyan troops and almost 400 tanks.2 But it was O’Connor’s very successes that had changed the course of the war in North Africa in the Axis’ favour. Hitler had been so alarmed by British successes in the desert that he had decided that he must support Benito Mussolini before Italy was completely knocked out of the war. In February 1941, while the British Army shuffled its pack, making O’Connor General Officer Commanding British Troops in Egypt and appointing Neame to Western Desert Force, advance elements of Major-General Erwin Rommel’s Afrika Korps had begun to disembark at Tripoli.

On 31 March 1941 Rommel had struck, launching a surprise counteroffensive that threw the Western Desert Force on to the defensive and saved the Italian Army. Matters had been compounded for the British by Winston Churchill’s insistence on sending men and materiel to Greece to aid the futile struggle there – Wavell simply didn’t have the units with which to stop the combined German–Italian offensive and was soon forced to give ground.

With O’Connor no longer in command of Western Desert Force, the new man had struggled to manage what was soon shaping up to be a losing battle. Fifty-three-year-old Lieutenant-General Sir Philip Neame was a sapper, commissioned into the Royal Engineers in 1908. Serious, of average height, precise and quietly humorous, Neame hailed from the Shepherd Neame brewing dynasty in Kent. A man of immense personal courage, during the Battle of Neuve Chapelle in France on 19 December 1914 he had single-handedly held up the German advance for 45 minutes by lobbing grenade after grenade at large numbers of enemy troops while a battalion of the West Yorkshires evacuated their wounded. For this extraordinary feat of arms Neame had been awarded the Victoria Cross. Even more incredibly, he had followed this up a decade later by winning a Gold Medal for shooting at the 1924 Paris Olympics, the only VC to ever have become an Olympic champion.

During leaves from the army Neame had pursued his other twin passions – exploring and big game hunting. He’d explored ‘all sorts of strange places where the natives were anything but friendly … climbed mountains in the wildest parts of the world, [and] shot all the most especially difficult kinds of big game.’3 In India, Neame had been clawed and almost killed by a Bengal tiger, and still proudly carried the scars.

Nicknamed ‘Green Ink’ by some of his contemporaries for his rather affectatious use of a green pen on all his correspondence, Neame had commanded a brigade in India between the wars before being appointed Commandant of the Royal Military Academy Woolwich in 1938, charged with turning out new officers for the army.

When Wavell, in desperation, had offered the newly knighted O’Connor command of Western Desert Force on 3 April 1941 he had refused, explaining that ‘changing horses in midstream would not really help matters.’ At Wavell’s request, though, O’Connor had agreed to ‘advise’ Neame, bringing with him the 46-year-old Brigadier Combe, lately commanding officer of the 11th Hussars, a regiment that had first won widespread public fame during the Charge of the Light Brigade in 1854. In true cavalry style, Combe had commanded a flying column consisting of out-of-date Rolls-Royce and Morris armoured cars that had cut off the Italian retreat at Mersa el Brega in early 1941.4 A good-looking man of medium height with brown hair and the ubiquitous military moustache, Combe had, like his boss, been awarded the DSO and Bar for his desert exploits and was tipped for higher command.

Following the decision to withdraw to Tmimi, the bulk of XIII Corps headquarters staff had left Marawa by 8.30pm. Only then had O’Connor, Neame and their closest aides left.

Their little convoy had originally consisted of three cars. Bringing up the rear of the convoy had been a Chevrolet Utility containing General O’Connor’s aide-de-camp, Captain John Dent, a driver and most of the senior officers’ baggage and bedding. Dent, though, had lost the other two cars an hour after starting out as they threaded their way through slow-moving columns of retreating British trucks.5

Now, Neame ordered his driver to turn off the main road to Derna and take a shortcut that he knew to Martuba. The driver was exhausted, and Neame took the wheel himself. The two big American cars thundered on through the dark desert night along the dusty road. After ten miles Brigadier Combe spotted a signboard that had been stuck to an old jerrycan beside the road and suggested that they stop and examine it. Neame refused, claiming that he knew the road and not to worry.

After driving for a further two or three miles General O’Connor was becoming uneasy, noticing that the position of the Moon indicated that they were heading north rather than east. He voiced his concerns to Neame several times, until Neame finally stopped and allowed his driver to take the wheel again. They resumed the journey, the officers nodding off in their cars until the drivers alerted them to another slow-moving convoy ahead.

In the second car Lord Ranfurly spoke to his driver about the convoy of trucks that was difficult to make out in the dim light as the cars were fitted with blackout-shielded headlights. A dashing Scottish aristocrat, the athletic 27-year-old Earl of Ranfurly, known as Dan to his friends and serving in the Nottinghamshire Yeomanry, was the sixth holder of the earldom.6 He was possessed of a very formidable and determined wife. Refusing to be left behind in England when Dan went off to war, Hermione, Countess of Ranfurly, broke every army rule and protocol and managed to get herself to Cairo where she was able to see her husband when he went on leave.

Up ahead, Neame’s car came to a halt. Ranfurly stuck his head out of the passenger window in the car behind and listened. Mingled with the sounds of the trucks’ engines was distant shouting – foreign voices. But it was too indistinct to attribute nationality.

‘Must be Cypriots,’ said Ranfurly uncertainly to his driver. The British had conscripted many Cypriots to drive supply trucks in the Middle East. ‘Just hang on here a minute,’ he continued, opening the door and walking over to Neame’s car. About to confer with Brigadier Combe, who had climbed out of the front passenger seat of Neame’s car, suddenly Ranfurly was aware of movement. A figure came out of the gloom and thrust an MP-40 machine pistol at his middle.7 Combe’s face dropped in astonishment.

‘Hände hoch, Tommi,’ growled the German. Ranfurly slowly raised both arms above his head. The German soldier, uniform coated in desert dust and wearing a tan-coloured forage cap, shouted for help.

Combe quickly turned to the car window and roused the dozing Neame and O’Connor. Combe reached into the glovebox and pulled out a hand grenade, stuffing it into his clothing.

‘Get down on the floor and remove your badges of rank,’ hissed Combe urgently at the generals.8

General O’Connor, looking around wildly as more Germans came running up to the cars, hastily unclipped his service revolver from its lanyard before shoving it inside his shirt, and then pulled off his rank slides.9 Seconds later, the car doors were wrenched open by German soldiers. ‘Raus, raus,’ yelled a German sergeant, pointing a Luger pistol at the officers.

The Britons were herded at gunpoint into a nearby hollow, where they would remain under guard for three nights. On the third day Neame and O’Connor revealed their identities to the commanding officer of the 8th Machine Gun Battalion, Oberstleutnant Gustav Ponath.10 He hardly dared to believe his luck. Within minutes Ponath was on the radio to Rommel with very good news indeed.

Ponath packed the senior prisoners off, with their ADCs and batmen, in a truck to Derna where they were handed over to the Italians, who had command authority over the North African theatre.11

In one fell swoop a massive blow had been dealt to the Allied cause. The Western Desert Force was suddenly deprived of its commander and the desert genius assisting him just at the most critical moment of Rommel’s offensive. The shock almost paralysed the British chain of command, deeply depressing General Wavell when he heard the terrible news.

*

Mechili, Libya wasn’t much of a place – just a name on a map of the barren Western Desert. Brigadier Edward Todhunter would describe it as ‘a horrible little place in the desert’.12 But it was where Michael Gambier-Parry’s war was to take a very bad turn for the worse.

On 25 March 1941, forward patrol units of Major-General Gambier-Parry’s 2nd Armoured Division had been attacked and El Agheila taken. Things had then gone quiet for a week before Rommel struck again on 1 April. The 2nd Division had been forced to withdraw, moving east towards Egypt in stages, fighting continuous sharp engagements with Afrika Korps panzer regiments. Rommel launched a pincer attack on the British division, using the Italian 10th Bersaglieri Regiment and elements of the German 5th Light Division and the 15th Panzer Division. The British and Indian troops, the latter the 3rd Indian Motor Brigade under the command of Brigadier Edward Vaughan, were exhausted by the pace of the operations and increasingly demoralised. On 4 April, Gambier-Parry, or ‘G-P’ as he was known to his friends, was given orders to block the Western Desert Force’s open left flank, but it was realised that though brave, the 2nd Armoured Division was inexperienced, short of personnel, ammunition and signal equipment; furthermore, G-P’s command of the division had left a lot to be desired. Among higher command there had been mutterings concerning a ‘lack of urgency and grip of the situation’.13

By the time G-P and his divisional HQ arrived at Mechili, 60 miles south of Derna, on the evening of 7 April, they were at the limits of their endurance.14 The 2nd Armoured Division, in the words of one senior commander, ‘more or less fell to pieces.’15

Forty-one-year-old Brigadier Todhunter was with G-P as the 2nd Armoured Division’s ‘Commander Royal Artillery’. His command group received sporadic shelling from German artillery on the morning of 8 April, as well as plenty of long-range machine gunning. This lasted all day until the evening, when the intensity of German shelling suddenly increased in ferocity and infantry began probing the perimeter. The British troops beat the Germans off this time, but casualties were mounting and the strategic situation was deteriorating all along the divisional front line as Rommel brought his armour to bear.

Todhunter had only been made a brigadier the month before, while he had been on leave in Cairo. Born into a landed family from South Essex, Todhunter had joined the Royal Horse Artillery in 1922 after leaving Rugby. He had thick, dark, oiled-back hair and wore black-framed spectacles that made him look more like a university professor than a tough and experienced soldier. Sent back to the front line in Libya, he had joined Gambier-Parry’s staff with the rank of Temporary Brigadier.

The British began to move again at first light on 9 April, always east towards Egypt and safety. Todhunter was tasked with organising some defence for divisional headquarters, Gambier-Parry and his staff having moved up to the front ‘unprotected and without any knowledge of how close the enemy were’.16 But Rommel was upon them instantly. ‘As soon as it was light enough to see we ran into really heavy shellfire,’ wrote Todhunter a few days afterwards. ‘Lots of it and fairly big stuff and a little further on we ran into a lot of machine guns and anti-tank guns.’17 Moving in their large Dorchester command vehicles, the division’s senior officers decided to turn the column south in the hope of outwitting the Germans, before resuming their withdrawal to the east. With G-P and Todhunter were Brigadier Vaughan (known to all as ‘Rudolph’) and his Indian soldiers and Colonel George Younghusband, a senior cavalryman and kinsman of the famous Edwardian explorer Sir Francis Younghusband, the conqueror of Tibet. Younghusband was GSO1 (General Staff Officer Grade 1), responsible for directing the battle and signing off Gambier-Parry’s orders. Younghusband had already impressed higher command, which noted that he ‘gave confidence’.18

‘Things looked pretty gloomy,’ wrote Todhunter at the time with commendable understatement. The withdrawal manoeuvre was doomed to failure as the British ran straight into large numbers of German tanks shortly after setting off.

Todhunter’s Dorchester had just crested a slight rise in the ground when six German tanks confronted him and his men. Infantry were firing machine guns, and anti-tank guns had opened up on the British column as well, brewing up several British tanks and armoured cars in a confused engagement. Within seconds German bullets peppered Todhunter’s vehicle, some armour-piercing rounds passing between his legs. One punched a hole right through his attaché case. Suddenly there was a terrific crack and the Dorchester rocked on its springs, smoke and dust filling the cabin. An anti-tank round had struck home, passing clean through the vehicle like a hot knife through butter.19 Todhunter and his staff hastily baled out, taking cover as the German panzers closed in. Within a few minutes it was clear that the headquarters of the 2nd Armoured Division, and those units helping to defend it, were not going anywhere. They were surrounded. Men began to raise their hands.20

Dust and smoke billowed across the hot battlefield as about 2,000 British and Indian troops laid down their arms over a large area and columns of German troops moved up to take their surrender. Todhunter’s staff captain turned to him.

‘Sir, there’s a good chance we can get away now, in all this confusion,’ he said, slightly wild-eyed.

‘I agree,’ replied Todhunter, looking about in all directions. ‘Look, you wander off and leave me. I’ll follow in a couple of minutes. At the moment I’m a bit too conspicuous in this bloody red hat.’21 He touched his field cap, its middle band the bright red reserved for colonels and higher. His shirt collar was also adorned with red tabs.

‘But sir,’ protested the captain.

‘Go on … get going!’ exclaimed Todhunter, clapping him on the shoulder. ‘I’ll be there presently.’

The captain reluctantly walked off, away from the approaching Germans, gathering men as he went. He managed to slip through the German encirclement and would make it to the British base at Mersa Matruh a few days later with 51 comrades, having also collected eight abandoned vehicles along the way to speed his escape.22

For Todhunter, his war appeared to be over. Another officer who escaped the encirclement reported a few days later that Todhunter ‘was last seen in the filthiest temper and using appalling language.’23 His foul mood was more than shared by all the other officers and men who were now ‘in the bag’.

*

An hour later, Michael Gambier-Parry stood and watched as a battered Horch staff jeep bounced its way across the rocky desert floor towards him. G-P hooked his thumbs into his gun belt, the holster now empty of its heavy service revolver, and waited. Standing beside him were three other British officers, the red tabs on the collars of their grimy shirts and red hatbands indicating their elevated ranks. Dozens of other British officers and men stood close by three large Dorchester command vehicles, giant armoured boxes on wheels the dimensions of those normally found beneath transport planes. Several British armoured cars and trucks lay scattered across the desert, badly shot up or still emitting plumes of black smoke into the clear blue sky, evidence of the ferocious battle that had ended not long before. German soldiers stood around cradling rifles and machine pistols in their arms, while medics from both sides tended to casualties wrapped in blankets on the dusty ground or propped up in the shade of trucks.

‘What do we have here, chaps?’ muttered Todhunter at Gambier-Parry’s elbow, his eyes fixed on the large staff jeep that had drawn to a creaking halt close by. Todhunter adjusted his spectacles, removing his cap to run the back of one hand across his sweaty forehead.

The others remained silent, George Younghusband reaching into his hip pocket to retrieve a silver cigarette case. He offered it around, but only Todhunter helped himself to a smoke, the stiff desert wind whipping the smoke away as he lit up behind cupped hands.

A German soldier, one of several dressed in the sand-coloured uniform of the Afrika Korps, dashed forward to the staff vehicle and quickly yanked open the passenger side door. A medium-sized, middle-aged German officer hauled himself out of his seat, one hand steadying a pair of large binoculars that hung around his neck, the other adjusting a button on his knee-length black leather great-coat that was grimy with desert dust. Several other field cars and half-tracks ground to a halt close by and staff officers, many festooned with map cases and signal pads, joined the senior German, who strode towards Gambier-Parry with an air of determination.

‘Well, I never …’ exclaimed Younghusband as he recognised the German general.

‘Gentlemen,’ said a young Afrika Korps captain formally, in good English, ‘allow me to present Generalleutnant Rommel.’

The Desert Fox, his keen dark blue eyes twinkling with good humour beneath the peak of his field grey service cap, stopped before Gambier-Parry, a friendly grin creasing his weather-beaten, tanned face.

‘General,’ said Rommel, touching the peak of his cap with one gloved hand.

‘Sir,’ replied Gambier-Parry, returning Rommel’s salute. G-P’s companions followed suit. So this was the great Rommel, thought G-P, looking the German over with renewed interest. The Britons watched as Rommel adjusted a patterned civilian scarf that was tucked around the collar of his coat, noticing the Knight’s Cross and the First World War Blue Max that he wore beneath. Rommel spoke to a young captain who was standing beside him.

‘My general presents his compliments,’ said Rommel’s interpreter, Hauptmann Hoffmann, ‘and asks for your names please.’

‘Gambier-Parry, Major-General, commanding 2nd Armoured Division.’ Rommel nodded, tugged off his right glove and proffered his hand. Slightly taken aback, G-P shook it. The German’s grip was firm and as dry as the surrounding desert.

‘Brigadier Todhunter,’ said G-P, pointing to the officer beside him, ‘Brigadier Vaughan, and Colonel Younghusband.’ Hoffmann made quick notes on a signal pad as Rommel’s eyes scanned each man’s grimy face. Then he said something in German to his interpreter.

‘My general enquires whether there is anything that you need?’24

For the next few minutes Rommel and the senior officers chatted amiably enough through Hoffmann. It was clear to G-P and his officers that Rommel was a decent sort, and certainly no strutting Nazi. His concern for their welfare and comfort would make a lasting impression on the British officers.

‘My general requests that you, General Gambier-Parry, join him for a meal, if you are in agreement?’ asked Hoffmann. G-P was somewhat surprised but accepted nonetheless. It was a surreal end to an extraordinary day that had seen the British suffer a crushing defeat. The past couple of days had delivered to the enemy a host of demoralised British senior officers, all victims of the Desert Fox’s tactical genius and aggressive handling of his small panzer force.

*

When Major-General Gambier-Parry arrived for dinner, he discovered that the Germans had erected a tent for the occasion. G-P seated himself opposite the Desert Fox, and over the next hour the two men, through the interpreter Hoffmann, swapped stories about the First World War, the desert, enjoyed good wine and at the end settled back to smoke ‘excellent cigars’.25 G-P was no stranger to the desert. An uncle of his, Major Ernest Gambier-Parry had been part of Kitchener’s expedition to Egypt to avenge the death of General Gordon at Khartoum, and he had published a book on the campaign in 1895, six years before G-P was born. G-P’s first personal experience of the desert had come in the First World War, when after winning a Military Cross in France and serving at the bloodbath of Gallipoli, he had fought the Turks in Mesopotamia. In 1924 G-P had transferred to the Royal Tank Corps, been a staff officer in London before becoming a brigade commander in Malaya. In 1940 the government had dispatched G-P to Athens as Head of the British Military Mission to Greece before promoting him to Major-General and assigning him command of the 2nd Armoured Division in North Africa.

As G-P rose to take his leave he noticed that his general’s cap, which he had left on a map table outside the tent’s entrance, was missing. He told Rommel, whose face took on a hard expression. Following Rommel outside, he watched as the Desert Fox made heated enquiries with junior officers until a few minutes later a young soldier was sheepishly brought before him holding G-P’s cap. Rommel was furious, giving the soldier a loud tongue-lashing concerning appropriate souvenirs and military conduct, before returning the cap to G-P with an apology.

G-P felt that he should in some way thank the Desert Fox for dinner and the fuss that had been made over his errant cap. Thinking quickly, he reached into his hip pocket and retrieved a pair of plastic anti-gas goggles and presented them to Rommel. The Desert Fox was clearly touched by the gesture, and immediately placed them around his own service cap.26 There they were to remain for the rest of his life, completing the image of the desert warrior that was to appear in so many photographs and newsreels before Rommel’s untimely death in October 1944.27

Rommel permitted G-P, Todhunter and Vaughan to keep their Dorchester armoured offices and later on 9 April the prisoners, aboard whatever of their vehicles were still in running condition, were escorted by German half-tracks and motorcycle combinations to the airfield at Derna, where they bedded down for the night. The next day the Germans took the 2,000 prisoners to old barracks in Derna. On arrival they were surprised, and not a little relieved, to discover that they were to be handed over to the Italian Army.28

*

‘It’s quite simple,’ said General Neame in a low voice. ‘We take over the aircraft and fly it to our own lines.’29 General O’Connor nodded vigorously, his whole demeanour since capture one of dogged determination to escape. General Gambier-Parry and Brigadiers Combe, Todhunter and Vaughan listened carefully to the plan during the short exercise time that the Germans permitted their prisoners each day at Derna. The group of senior British officers strolled around a dusty parade square in the dirty old barracks complex, puffing on pipes and cigarettes as they went over Neame’s plan.

‘Phil’s right. It’s obvious that the Jerries are going to shift us to Germany, and soon,’ said O’Connor to the brigadiers. ‘We’ve worked out a plan to hijack the plane that takes us to Berlin.’ The fear was that the generals, because of their high ranks and command responsibilities privy to a vast amount of top-secret information, might be handed over to the Gestapo once pressure had been put on the Italian authorities under whose nominal authority they remained for the time being. At the very least, they could expect detailed and long interrogations by German military intelligence. The intelligence windfall for the Germans could potentially change the course of the war for Hitler.