Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

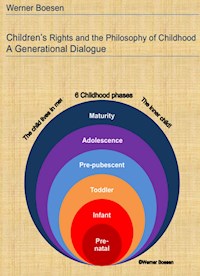

The philosophy of childhood is still a young science area. Human being is childhood and adulthood and requires communication, a dialogue. The dialogue philosophy offers an integrative basis in the interdisciplinary context of psychology, biology, pedagogy, sociology, law and religion: •What is childhood? •Which natural law does a child have? •Who carries the responsibility for a child? •Which stages of childhood development can be differentiated in dialogue philosophy? •What means the generation concept for childhood and adulthood? •What is the basic thesis of education? •Which myth (fairy tale) was paved the way for our state constitution? •Which parenting conflict remains unsolvable? •What fundamental rights are missing in the United Nations Convention on the rights of child? •Which rights and duties can be deduced from the self-understanding of nature? Towards adulthood being a child means a weaker position and the risk of abuse. In the childhood-philosophical sense, an answer to the risks of being a child and the best possible protection of the child is required. The legal foundation is the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. But we do not reach the children with laws. It takes more than just dialogue and parental care. There are controversial arguments in politics and science. The author finds clear answers.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 109

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Children's Rights and the Philosophy of Childhood: A Generational Dialogue

ImprintA GENERATIONAL DIALOGUEPreface and AcknowledgementsIntroductionThe dialogue philosophic ApproachChildren’s Rights: Between permanence and changeThe mediation and enforcement of children's rightsI & You, static and dynamic childhood developmentQuestions and Answers at a GlanceLiteratureImprint

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Internet content: every internet and literature sources have been checked before publication. It cannot be guaranteed that all sources still exists but this does not change any knowledge and experiences provided in this book. A liability for any external source disclosures or references is alwayx exluded by the author.

Bibliographic information of the German National Library:

The German National Library lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; Detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet athttp://dnb.dnb.de.

Texts: ©Copyright by Dipl.-Kfm. Werner Boesen

Cover design: ©Copyright by Dipl.-Kfm. Werner Boesen

Publisher: Dipl.-Kfm. Werner Boesen

Robert-Schumann-Weg 3

D-67251 Freinsheim

www.wernerboesen.de

Druck: epubli a Service of neopubli GmbH, Berlin

ISBN: 978-3-748521-08-2

Printed in Germany

CHILDREN’S RIGHTS AND THE PHILOSOPHY OF CHILDHOOD

A GENERATIONAL DIALOGUE

Statics and dynamics of humankind

‘I’ and ‘You’ are children of nature and cosmos, for the believers God’s children (Joh 1, 12; LUT)!

Preface and Acknowledgements

The present study was developed as part of a project at a German university and deals with the following the framework topic: Generations – Between Consistency and Change. My focusses centered on the first and second generation ofbeing human, children and adults, and adults as parents. In my attempts to develop a basic scientific discipline, I discovered that there were many disciplines available here. The foundation of my analysis became the philosophy and integration of basic human knowledge of other disciplines of science, such as psychology, sociology, education, and law. In philosophy, I stumbled across a variety of sub-disciplines and I finally chose the childhood philosophy, a young research direction primarily in the American cultural space. In the German-speaking world, the term “child ethics” is commonly used, which refers to the moral behavior of mankind, and is therefore restricted to the general concept of philosophy which was limiting. Even the term “philosophy” in one of its possible definitions refers to the “love of wisdom” and gave me the direction for the following questions: What is love, what is wisdom? and what connects it to childhood in human existence? The framework topic in the project pointed me to a solid relationship, verbal and non-verbal, of generations, and their agility “between permanence and change,” for which dialogue is imperative. The anchor for this was offered to me by the philosophy of dialogue, a predominantly religious-philosophical subdiscipline that differentiates two people, as well as nature and the cosmos. This involves a twofold relationship, that of the ego (the “I”) and the thou (the “You”). It was also of general interest to consider the current legislation on children’s rights. The basic work and concerns here are the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child and their application within national constitutions, which only a few countries have implemented to date. It should be noted that the Convention on the Rights of the Child, not only in the philosophical sense, does not meet all the requirements of the child. This will be dealt with more comprehensively in the upcoming study, including a religion-specific view on the example of Christianity.

This project study was restricted to a certain number of pages. The specification was based on about 40 DIN A4 pages. It was extremely challenging for me to limit the content to this page specification and it is not enough that questions arise. I have therefore attached a questionnaire with possible answers for publication. It was also important to me to publish this work as both a German-language and English-language publication, as the childhood philosophy is underrepresented research publications in the German-speaking world.

In particular, I would like to thank the lecturers of the project study for their contributions to the discussion and critics, as well as Dr. phil. Laura Marwood for her assistance in fine-tuning the English translation.

In fond memory of my most recent childhood, I dedicate this work to my beloved Mother and would like to thank the private, state and religious communities for their loyal education experts (Loyal’ here means committed to pure doctrine. This excludes abuse. That should be synonymous with the term ‘education expert’, but the use of a thing carries the risk of abuse).The ‘I’ grows on ‘you’!

Introduction

The philosophic view on children’s rights includes the whole childhood. ‘The philosophy of childhood has recently come to be recognized as an area of inquiry analogous to the philosophy of science, the philosophy of history, […]’ (Matthews/Mullin). When examining the notion of childhood, one must take the various existing theories and cultural understandings into consideration. As David Archard contends, ‘The modern conception of childhood is neither a simple nor a straightforwardly coherent one, since it is constituted by different theoretical understandings and cultural representations’ (Archard 2015 p. 53).

‘The conception is a very modern one inasmuch as literature has treated of childhood for only two hundred years, and science one hundred’ (ibid.). Human history has existed in our modern understanding for 100,000 years (Diamond p. 209), and humankind is specifically characterized by childhood and adulthood: ‘Developmental science views childhood as a stage on the road to adulthood, and the nature of the child as impelling him or her to the achievement of the adult capacities […]’ (Archard 2015 ibid.). What we understand by childhood is a permanent relationship, an interaction with adults, and vice versa. The relationship is founded on communication and a dialogue between the child and adult, a dialogue between ‘I’ and ‘You’. Philosophical anthropology serves as a theoretical basis here (Philosophic discipline, in general the anthropology, see Lorenz 2014 in Brandt 2014 p. 470). A key feature is dialogue thinking, otherwise known as the philosophy of dialogue (Definition i.e. Hügli 2013 p. 189 keyword ‘Dialogphilosophie’. All citations from Hügli are translated from the German into English by W. Boesen for the purpose of this study). According to this philosophy, all humans assume both roles. ‘I’ is the active role and ‘You’ the passive (See Lorenz 2014 in Brandt 2014 p. 487). In the ‘I-You-Relationship’ the ‘I’ meets the other that is not only ‘You’ as a human, but can be also an object or God (Defined by Martin Buber, see Gessmann 2009 p. 333 Keyword ‘Ich-Du-Verhältnis’. All citations from Gessmann are translated from the German into English by W. Boesen for the purpose of this study). The knowledge of the experience of ‘I’ and ‘You’ ‘happens in this process empirical at the transition of I-telling in earliest childhood to I-suffering in puberty’ (Lorenz 2014 p. 489, translated by the author, German text: Das Wissen um die Erfahrung des Ich und Du ‘geschieht dabei empirisch beim Übergang vom Ich-Sagen in der frühen Kindheit zum Ich-Erleiden in der Pubertät). A precondition for ‘I’ and ‘You’ is rational behavior that is ‘documented in reciprocal delimitation [...] especially with rationale competencies’ (ibid. p. 478). Hence the child needs an adult as a reliable advocate. Where reliability and obligation involve risks of failure, this must be hedged by public law and observed by legal authorities. The following discussions deal with different childhood phases in dialogue context and will attempt to shed light on the main important dialogue-philosophical legal positions in the relation of childhood and adulthood. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child will serve as the basis for a comparison of legal positions (Commonly abbreviated to UNCRC.). Archard offers an analysis on this subject in his work with ‘Children: Rights and Childhood (‘[…] widely regarded as the first book to offer a detailed philosophical examination of children’s rights’, Archard 2015, first page after cover).’ The Basic Law of the Federal Republic of Germany is briefly discussed in relation to philosophic anthropology (see Lorenz, Kuno (2014) in: Brandt 2014 pp. 470 ‘Philosophische Anthropologie’…in general “Doctrine from mankind‘, p. 470 …reactive und reflexive discipline p. 471) and Dialogue Philosophy (See Hügli/Lübcke (2013): Dialog philosophy description for ‘dialogic thinking’ p. 189). A view on the 100,000 years of human history will indicate the archaic understanding of childhood. This study will finally explore the dynamic view of childhood based on the writings of late 18th-century German philosopher, Immanuel Kant (main important German Philosopher, 1724-1804, see Gessmann p. 375)

The dialogue philosophic Approach

The dialogue philosophy (also known as ‘dialogicalism’ or ‘I-You’ philosophy) refers to the dialogue to the ‘You’ (Gessmann 2009 p. 168, Hügli 2013 p. 189). The ‘I’ is formed by ‘You’ (Gessmann ibid.). This relationship has essential importance and constitutes a fundamental experience of human life (ibid.). A human becomes a person through the ‘integration of I-role and You-role […]’ (Lorenz 2014 p. 476).

Dialogue philosophical basic concept

The word ‘dialogue’ and the personal pronouns ‘I’ and ‘You’ are the initial conditions of dialogue philosophical analyses.

The dialogue

The word ‘dialogue’ derives from the Greek and refers to a ‘communicative relationship between twopersons[…] to reachwisdom, […]’ among ‘persons who areaware of themselves[…]’ (Hügli p. 189). Originally, dialogue describes the ‘literary art form as a representation of the Socratic dialogue Art’ (Gessmann p. 167).

A communicative relationship is more than a mere conversation. Communication means ‘doing together, taking part in something, talking’ (Hügli p. 488). It is necessary to differentiate between verbal and non-verbal communication, the first of which refers to the spoken word and writing, whilst the second form comprises non-written forms (ibid.). A dialogue always includes two or more persons. The word ‘person’ is used ambiguously (‘lat.persona, mask, character, role’, ibid. p. 681), and means ‘identification for the ‘I’, […] insofar beside consciousness […] owns a body […] has an individual history, […] develops into an own personality […]’ (ibid.). In addition to consciousness and physicality, there is relationship to a person from body and soul and the other minds (ibid. part 3). ‘Other minds’ are conscious states that belong to ‘other persons or animals’ (ibid. p. 303). ‘Person’ refers also to a collective, such as a society and state, called legal person, ‘insofar they have rights and duties’ (ibid. p. 681 part 2). Furthermore, ‘person’ can be used in an abstract sense, which is known as ‘personification’, such as the term ‘mother earth’ (Meyer/Regenbogen p. 490/491).

In strong relation with person, the term ‘personal identity’ is often used frequently (Hügli. p. 682 part 4 ‘persönlichen Identität’): ‘persons are changing, […] what does it mean if they are still the same person? What connects the adult with the child they once were before becoming an adult?’ (ibid). Does it mean in the dialogue the child acts in the person? The person is placed on an ‘immaterial substance (i.e. the soul)’ or memory despite of memory gaps or illusions (ibid.). The child has no relevance as person. Especially for very young children, the term person is clearly irrelevant, ‘[…] since typical criteria of some humans for defining a person (i.e. very small children […] are missing’ (Gessmann p. 544). The constraint only applies to very young children. Children are not generally excluded from being a person. The term ‘person’ is not fully describable and gives only an orientation that is normative in nature (ibid.). The term ‘rationality’ is also significant (ibid. p. 545). Due to typical missing characteristics describing human beings as people, it is helpful to ‘have an appropriate representative, […] for related regulation matters’ (ibid. referring Jürgen Habermas 2005, philosopher and social scientist, born 1929 Düsseldorf, see Gessmann p. 287). ‘Cultural norms that create solidarity also among strangers need to be accepted generally. We need to admit discourses to evolve such norms’ (Habermas p. 21, German text: ‚Normen des Zusammenlebens, die auch noch unter Fremden Solidarität stiften können, sind auf allgemeine Zustimmung angewiesen. Wir müssen uns auf Diskurse einlassen, um solche Normen zu entwickeln‘.).

The dialogue is personal in nature, ‘In a conversation, I will talk to another person who is addressed as You, and who also addresses me as You’ (Hügli p. 189). The conversation is also self-talk,’ […] if the individual is conforming to the attitude of the other, especially if these attitudes are shared by a whole group […]’ (Mead p. 79). In addition to personal dialogue, trans-subjective dialogue is also possible. ‘Trans-subjective’ means ‘beyond the subject (the ‘I’), also beyond consciousness, not belonging to a conscious process’ (Meyer/Regenbogen 2013 p. 671). This is a widespread view in the philosophical doctrine of personalism, which ‘considers humans […] primarily as active and evaluative persons’ (Hügli S. 683) and appreciates humans as ‘persons contrarily to a kind of potential objectification […] especially turns against any forms of reification of a human being’ (Gessmann p. 545). While personalism focuses on a person, dialogue philosophy acts on the relationship between persons, and accentuates the ‘direct character of these relationships’ (Hügli p. 684). An extension is made in theology, whereby personalism is explained with ‘a conversation between God as a person to humans insofar a human is facing each other and will be You for God’ (ibid.). God is ‘in general, an expression for a supernatural, attractive and challenging power that is either delimited or all-embracing and mostly imagined personally’ (Gessmann p. 278). The personal imagination of God is transcending personal reality and can therefore be called transpersonal. While in philosophy, the term ‘trans-subjective’ is commonly applied, the term ‘transpersonal’ is known from transpersonal psychology (Walach 2014). A main area in transpersonal psychology is ‘to explore and find those dimensions beyond self-development, also the spirituality that transcend sense and experiences like Being and Time’ (ibid.).