Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

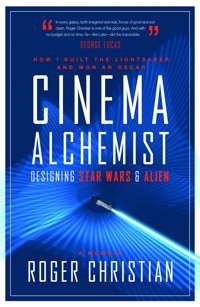

For the first time, Oscar-winning production designer and director Roger Christian reveals his life story, from his earliest work in the British film industry to his breakthrough contributions on such iconic science fiction masterpieces as Star Wars, Alien and his own cult classic Black Angel. This candid biography delves into his relationships with legendary figures, as well as the secrets of his greatest work. The man who built the lightsaber finally speaks! With Forewords by George Lucas, David West Reynolds and J.W. Rinzler.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 762

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Cinema AlchemistISBN 9781783299003eBook ISBN 9781785650857

Published by Titan BooksA division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd.144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UPUnited Kingdom

First edition: July 20162 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

TM & © Roger Christian

Did you enjoy this book? We love to hear from our readers. Please e-mail us at:[email protected] or write to Reader Feedback at the above address.

To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive offers online, please sign up for the Titan newsletter on our website: www.titanbooks.com

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

CONTENTS

COVER

TITLE PAGE

COPYRIGHT

FOREWORD BY J.W. RINZLER

AUTHOR’S NOTE

PREFACE

CINEMA ALCHEMY

Lucky Lady—the road to Star Wars

Star Wars: how it began

STAR WARS

Once Upon A Time In The West

Djerba

Tozeur

Final day’s prep for Tunisia

Star Wars first day shoot looms

Star Wars becomes a movie

British attitude at the time Star Wars was made

Twin suns—a hero’s journey moment

Problems mount for George

Star Wars summation

Marty Feldman’s The Last Remake of Beau Geste and the Sex Pistols

MONTY PYTHON

ALIEN

Standby art director

Dan O’Bannon

Nick Allder and Brian Johnson: SFX

Nostromo bridge set

The crew fire up the Nostromo

Tension on the set

Ridley punches through the bridge ceiling

Jones the cat in the locker

Crew quarters

Nostromo commissary

Mother

BACK TO LIFE OF BRIAN

Back to film school

BLACK ANGEL

The script

Where do stories originate?

The true origin of my story

The script evolves

Vangelis

Giant heavy horses

Black Angel: Day 8

STAR WARS: RETURN OF THE JEDI

FINAL WORDS

Star Wars

Alien

Black Angel

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

FOREWORD

BY J.W. RINZLER

Once upon a time, while doing research in the Lucasfilm Image Archives, I came across a mysterious photograph. At first I didn’t know who the five people in it were, but there was an unmistakable aura about the group. Sometimes an energy is present when a photo is taken that can make itself felt many years later, even a century beyond its time. In this case it was about thirty years later and the group soon revealed itself to be the English art department core of the first Star Wars film: production designer John Barry, art directors Norman Reynolds and Les Dilley, construction supervisor Bill Welch—and one long-haired twenty-something, who looked like he might be a visiting rock star: Roger Christian, set dresser and provocateur.

For it was Roger, in league with John Barry, who hit upon the idea of a used universe.

This greasy, worn out world became, in late 1975, the ingenious answer to multiple questions at the time. The big quandary had been, How on earth would the art department build the multi-set visionary worlds George Lucas had dreamt up, given their tiny budget? Linked to that question was another: How would they differentiate Star Wars from its low-rent trashy sci-ficousins? (2001 excepted, but that was an art film.)

To make things that much harder, just before principal photography was to begin, Twentieth Century Fox, their very reluctant studio backer, had slashed their budget from $8.2 to $7.5 million, ten percent of which reduction came directly out of the art department’s coffers. Christian’s work-around brainstorm, based on years of experience under several genial mentors, was to source a cheap supply of odd materials, consisting of pre-fabricated realistic shapes, forms, and ideas; junk, that is. Lots and lots of junk: airplane junk, washing-machine junk, plumbing junk. He would also sell Lucas on the idea of real, but enhanced, weapons to stand in for the script’s blasters and lightsabers.

I’ve written about some of this in The Making of Star Wars; it was while doing research for that book that I found said photo, in an old binder of black-and-white film. That book was the best job I could do as an outsider, decades after the fact (though relying on contemporary interviews). So when Roger told me he was writing his own memoirs, and as I came to appreciate his phenomenal memory for both details and the big picture, I was thrilled. His account would be—and now is—the story of someone who was right there: meeting with George Lucas in Mexico early in preproduction; standing with him as the studio dithered, and then, while prepping the sets, watching Lucas’s back in Tunisia and at Elstree Studios. His account of the enormous uphill battles and mind-bending challenges of the shoot are unrivaled.

Afterward Lucas rewarded Christian’s ingenuity and loyalty with matched loyalty, helping him become a director, in turn, by backing his live-action short Black Angel. That short has recently been revived (a fascinating story) and its influence acclaimed. Roger’s account of his low-budget independent filmmaking, as he cobbled together talent and resources to make Black Angel a reality, should be required reading for film students.

Roger then returned Lucas’s backing, jumping in when needed as second-unit director on Return of the Jedi and The Phantom Menace. In later conversations Lucas would refer to Christian, Barry, and a paltry few others as those who had saved his quirky little space fantasy from disaster, helping it become the undreamt-of phenomenon it is today (though they did think that it would be successful even at the time).

Yet Roger’s is more than a book about Star Wars. It is unlike any other film book that I’ve read in that it presents, unvarnished, the raw emotional world of the craftspeople and artists, the producers, directors, and actors, who often toil in impossible conditions under great duress—long hours, life-threatening illness, and internal foes—because they so love what they are doing.

This is never more evident than in Roger’s further adventures during the making of another classic film, the horrifying and beautiful Alien, an art-directing job almost immediately after Star Wars, on a film that would have almost as great an impact on cinema. The vicissitudes he colorfully describes feel real; his portraits of his contemporaries are insightful and compassionate (although a few receive naught but righteous wrath); and his descriptions of London life during one of its creative peaks, during the 1960s, 70s, and early 80s, is a lot of fun, as he rubs shoulders with the Rolling Stones and other luminaries (the book even has a side of Monty Python’s Life of Brian).

So if you want to find out how a wily artist matched wits with the likes of George Lucas and Ridley Scott, how integral art departments functioned during a British heyday of film creation on the first Star Wars and Alien, how an Academy Award–winning director crafted an enigmatic tale from nothing, and how death was defied in devotional service to the silver screen, then, by all means, read on…

J. W. RINZLER

AUTHOR’S NOTE

When I was having my first interview for a job in the film industry as tea boy to the art department on Oliver!, production designer John Box gave me this advice:

“You are alone in the desert, standing next to a silver airplane with a bottle of green ink in your pocket. A cloud of dust approaches nearer and nearer as the director and producer arrive. The director looks at the plane and says, ‘Great, this will work, can you have it red by tomorrow morning?’ You either do it or talk your way out of it there and then. That’s the film industry.”

These wise words have served as my mantra throughout a long career and in no small way came to full force when I was asked to set decorate Star Wars on a budget that most people would have said, no; it cannot be done.

PREFACE

The title for this book came from my coming up with the idea to make all the interiors of the sets and props on Star Wars from scrap metal and old airplane parts, and being rewarded with an Academy Award for it. I signed on to set-decorate Star Wars in August of 1975 having met George Lucas in Mexico earlier that year while working on Lucky Lady. Being asked to come up with props, guns, and robots, new inventions in George’s script like a lightsaber, Luke’s speeder and a diminutive robot called R2-D2 and the golden C-3PO took a huge leap of faith and confidence. The initial budget at that time was four million dollars and my set-dressing budget a tiny two hundred thousand.

Even in those times this was hardly enough for John Barry, Les Dilley, and me to create this world imagined and beautifully illustrated in Ralph McQuarrie’s paintings. My first conversation with George Lucas in Mexico revolved around a common language, that science-fiction films had portrayed unrealistic sets and props that were all new and plastic-looking. We had a common goal—to make a spaceship that looked oily and greasy, and held together like a very used second-hand car. Thus the Millennium Falcon, looking like a cross between an old submarine and a used spaceship, came about, a philosophy extending to every detail, including the props and guns and all dressing.

My path to making Star Wars and my experiences made it possible to reach far outside the conventional way I was brought up, and prepared me to go out on a limb and suggest to George Lucas new ways to dress the sets, like buying old airplane scrap and breaking it down and using it to create the Falcon’s interiors. My pet peeve was sci-fi guns that looked and sounded like toys, so I suggested using real guns and adapting their look for Star Wars. My luck was having a director who was an independent filmmaker who, having made a very low budget science-fiction film, THX 1138, did not flinch when I presented untried solutions to the then insurmountable problem of making all the dressings and props.

Alien was exactly the same, and under director Ridley Scott I was able to take further my ambition to make a spaceship that looked like we had rented an old and used space truck.

This book in some ways illustrates how my independent thinking enabled me to be a part of Star Wars: A New Hope, arguably the best-known and most successful film of all time, an enduring classic that deserves its place amongst humanity’s great myths and legends, and Alien, which has also become a cinema classic, the chestburster scene being recognized as one of the seminal moments of modern cinema.

I think John Barry’s speech on accepting the Academy Awards for Star Wars says it all.

* * *

“We are very pleased to accept this beautiful award on behalf of all our friends and compatriots who worked so hard to make the sets of Star Wars a success. And there’s one man whose name should be engraved on this above everybody else and whose name should be on every frame of Star Wars, and that’s George Lucas. Thank you, George.”

CINEMA ALCHEMY

LUCKY LADY—THE ROAD TO STAR WARS

Ring… ring… ring…

* * *

The ringing of the phone cut through my apartment. I was watching a tennis match at Wimbledon on the television and wondering, as were the players, if it was going to rain again or even snow as predicted by those illustrious television weathermen. The old fishermen’s way to predict the weather was to hang a bunch of seaweed outside the door and simply feel it with their fingers and smell it. They would tell you, in their broad Devon or Cornish accent, exactly what the weather would be and they were almost one hundred per cent accurate.

This serves well as a metaphor for my way of working as a set decorator, art director, and a director. I still use the lowest tech way possible on the shooting floor, which saves money and time, and gives a reality to the images. My effects supervisors all know that I used to minimise motion control from my main unit shoots, for ‘watching paint dry’ is the correct metaphor for that agonizingly slow process. This came to be the most valuable skill when I was offered Star Wars with a tiny budget at the time to make such a cinematic epic.

“Hello, hello, hello?” The voice at the end of the phone was insistent. “Is Roger Christian there? I’ve been trying to find him.”

“Yes, it’s me. Who is this?”

“It’s Graham Henderson, from Twentieth Century Fox. I’ve had a call from the production designer, John Barry. He’s working on a film called Lucky Lady in Mexico. Les Dilley’s out there with him. They need another person in the art department urgently, and suggested I call you to see if you are available.”

“When would they need me?”

“Can you get on a plane immediately to Mexico?”

“Yes, I could. Where to, and what for?”

“You’ll never have heard of this place; it’s a small city on the west coast of Mexico called Guaymas.”

“Guaymas, funnily enough I have been there. It’s stunningly beautiful; I remember the pelicans diving in the bay.” I had taken a trip around America with an actor friend of mine, Chris Plume, and we had taken a Mexican bus from San Diego to Guaymas and stayed three nights there in a shack on the beach.

This offer came after a long history of working experience and connections, but it was clearly the moment that the journey to Star Wars began.

I read the script of Lucky Lady on the plane flying across the Atlantic. It was written by Gloria Katz and Willard Huyck, a married team, and it was one of the best scripts I had read. A fast-paced and original drama set around the illegal rum running that took place between Mexico and America during prohibition, the movie centered on a triangle of characters living in Mexico. A ménage à trois composed of a nightclub singer played by Liza Minnelli and two wonderful characters vying for her attention but glued together as best friends played by Gene Hackman and Burt Reynolds. They were huge box office stars at the time, so it was a tantalizing mix.

The movie was an epic production financed by Twentieth Century Fox that was growing in size weekly under director Stanley Donen. They needed another assistant art director to work as set decorator to help the tiny British art department working under production designer John Barry. If I had been asked to make John Barry’s tea I would have happily gone. He had designed Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange and was one of the most gifted designers working. Les Dilley, my long-time art-directing partner, was already there and had recommended me to John for this; Norman Reynolds was the other art director. They comprised the entire art department. When one considers this was a period film set in the twenties and involved over fifty ships fighting battles on the ocean between the rum runners and the coast guards, as well as being a movie that required the building of a plethora of sets, it was a very small department to handle it all. Now that the film was running way over schedule and budget, they needed the extra help.

Filming with boats is worse than working with animals and robots! It was a huge endeavor. Anything to do with boats is truly one of the worst situations for any director. Controlling them is so difficult, especially on the ocean, as they constantly move and change position with the tidal movement, so it’s really hard just to get them all in place for a shot. If a boat shifts position, it takes ages to move it back to the right spot and by then all the others have shifted. Then, of course, there is the unpredictable weather as well. Fifty boats, one of them a large navy destroyer with weapons and guns fighting huge sea battles as the coast guards tried to apprehend the rum runners, made it all horrendous. And this was only one part of the movie…

The problem with the production running way over schedule, aside from the budget swelling, was twofold: the worst was the heat as it escalated towards mid summer; the second was that the crew was needed to move south to Mexico City to complete the shoot, so a second crew would be left in Guaymas to carry on filming the sea battles. The stars had a contracted number of weeks and going over schedule meant paying huge overages.

I met John Barry and Norman Reynolds and went over what I had to do. John had designed and created wonderful sets in the studios and had also built into existing buildings on location to give them an authenticity. He took me to the nightclub set, which was evocative of the Mexican clubs of the thirties full of color and glitter. They had already filmed part of the sequence here, so it was dressed and lit.

Liza’s character was a torch singer, a classic diva, and the set created a perfect atmosphere for her song performance with a wrought-iron staircase dominating the main room for her to descend as she sang.

John quickly fathomed out where I would be most useful and put me in charge of dressing the old rum factories, a salt factory, and a houseboat that was a hippy traveler’s boat. This was written in the script as being covered in junk and flowers and plants, and no one knew what to do with it. It played a prominent role in the film, however, so it was important that it looked right.

I needed junk and scrap to dress the sets that were being constructed by our construction manager Bill Welch and his team to make them look authentic, particularly the houseboat. We were in a country where roughly half of the population of Guaymas lived in shanty towns constructed from cardboard boxes, soft drink cans, anything that could be found and used. These shanty towns spread out around Guaymas on every available hillside. Guaymas itself was a prosperous fishing town; the bay was absolutely packed with every variety of fish: the famous red jumbo prawns, sardines, and blue marlin.

Anything that could be caught and eaten was there in huge numbers. The labor for the canning factories, fishing boats, and the luxury hotels dotting the coastline came mainly from the shanty towns. Scrap was therefore just not available; anything of any use whatsoever was recycled and used again.

Somehow through all this we bought enough junk and scrap to dress the sets. I managed to create a wonderful old boat covered in plants, furniture, old bicycles, etc. It was covered from bow to stern in a wonderland of junk that gave it a really strong hippy character. This experience was still fresh in my mind not long afterward when another film came along…

STAR WARS: HOW IT BEGAN

Meeting George Lucas and Gary Kurtz

One really interesting old set I had to get finished and dressed was a salt factory, a beautiful old period set with peeling paint and faded walls. We had to cover all the ground around it with salt where the bags would have been stacked and loaded onto cargo ships. It was built near the ocean so that trucks could transport the sacks of salt for delivery.

That evening at dinner John told us that a producer and director were flying in to meet us the next day and look at the sets. George Lucas and Gary Kurtz were friends of Gloria Katz and Willard Huyck, who had recommended us for a science-fiction film the director was making. He was looking for the same ‘used’ style of sets and Twentieth Century Fox had told George Lucas that he could make the film if he made it in the UK for the budget they had allocated. We had become great friends with the Huycks; they were married but kept separate professional writing credits. Gloria and Willard had written the first draft of Radioland Murders for George, and had polished and rewritten dialogue for George on the last draft of Star Wars. They loved John Barry, not only for his precocious talent as a designer but also for his intelligence and humor.

Next morning I was out in the midday heat shoveling white salt with the prop-dressing gang and our local Mexican crew. It was supposed to be a run-down factory in the script and to stand indistinguishable from a real building that had been there for a good hundred years. We had a sign painted across the wooden front saying salt factory in faded and peeling letters. I’d had the painters age down the wooden boarding using a technique that John Box had taught me when I started my career on Oliver. They used a clear glaze and added in paint colors like old greens that gave it a patina that usually comes only after years of weathering. Then with blowtorches I had them burn the lettering and paint back, as if years of intense heat had dried and cracked it. I dressed suitable carts and an old car around the front to add character. We had a wrecked boat as well, so the set looked absolutely natural and weathered, as if it had been there for years.

The set was almost finished and ready for shooting. We were just adding the final touches when a car arrived and pulled to a stop. Two figures got out looking more like film students than a Hollywood director and producer. George Lucas was in his now familiar plaid shirt, jeans, and sneakers that was his daily wear and still is, and Gary Kurtz in a similar look, I think, with his hat to ward off the relentless sun. George and Gary came across and introduced themselves to me.

George looked at the set and was really surprised to find it was not an old factory but a specially built film set. I took him round the back and showed him what we had built, as behind the ancient façade was nothing but timber scaffolding. George asked a lot about the aging techniques, the salt and the dressings I had carefully placed around. He talked briefly about a science-fiction movie he was about to start and wanted the same patina look and detailing, everything natural and used, not science-fiction designed. We talked about some of my history and working with John Barry. George even helped me with dressing the salt and got stuck in, spreading some around with a shovel as I explained how I saw science-fiction crafts and worlds: old oily ships, distressed from use, somewhat like a mix between a submarine and a bomber cockpit. I disliked the overly designed plastic worlds prevalent in films of that genre, with the toy-like weapons and gray uniform-style costumes based on communist-era dress that they always seemed to have. It all looked totally unnatural to me and unbelievable. George agreed. His vision, he told me, was more of a dusty Western combined with 2001. I understood immediately.

They went on to meet with Geoffrey Unsworth and I was invited to catch up later with him and Gary at dinner.

That night under the stars in the courtyard of the hotel, a little cooler after the sun had gone down but still incredibly hot, George talked to me and John about his movie at length and his aspirations. George had met and liked Geoffrey, and respected his immense talent. Among many legendary movies he had photographed were 2001 and Cabaret. He was a natural choice. Lucky Lady was looking a lot like a dusty Western filmed on location. Moreover, John, Gloria, and Willard explained that Geoffrey was a wonderful and talented director of photography, and an enormous help to his directors.

George and Gary left the next day. I found out later, when we were in Los Angeles, that George had hired us for Star Wars, or The Journal of the Whills as it was called then. I was the third person hired. First was John Barry as production designer, and then Geoffrey Unsworth as director of photography, and third was me as the set decorator (noted in this order in the official book, The Making of Star Wars). Fourth was Les Dilley, but, being standby on the shooting floor, he had not managed to meet George on that trip. John’s intelligence, his passion for film, and his understanding of what George was looking for visually, had given George the confidence that we could be trusted to create his vision for this space epic.

The heat during the day was becoming intolerable as the movie ran more and more over schedule. It was so intense even the Mexicans were complaining and saying we were crazy to be working such long hours in this heat without the afternoon siesta they were accustomed to. Working at sea most days on the boats, there was nowhere to hide from the fierce sun. Umbrellas did their best to keep the rays off the cameras and crew, but working at a high pace meant ignoring the conditions and getting on with it.

Many of the crew got sick; it was inevitable. We did what we could to try to keep safe, but in the end some form of bacteria will get you. British crews tend to go on working and grin and bear it, unless it’s really bad. I was no exception and carried on despite some form of typhoid infection I had obviously contracted. I remember Rudy, the wonderful Mexican assistant assigned to me with a face deeply lined with a life of experience, saying to me one day in late June, that we should not be working in this heat, but I didn’t feel I had a choice.

I was carrying on, despite being as sick as a dog. My weight was down to under nine stone. My jeans were falling off me, but being tanned from the relentless sun, the glow of my skin after months in it did not betray how ill I was. The end of the shoot was in sight and I did not want to give up. All I was passing now from my many visits to the Mexican-style toilets was a small amount of thin green liquid. That only happens when the kidneys and liver are near to giving up.

The next morning I awoke feeling really exhausted. I walked out of the house into that wall of heat and felt instantly nauseous and weak. I got into the car and turned on the air full blast to try to cool down, but it was the same futile effort as every other day. I drove to the docks where all the boats were docked every night. I had the local boatman take me in the small motor launch to the boat where the camera crew was setting up for the day’s filming. When we arrived I realized as I climbed up the steps to get on board that I had zero energy left. I could barely make it up the ladder to the deck. I felt as if I was about to pass out. I had no liquid with me, and was gasping with thirst. I was so weak I finally succumbed to the realization that I could not carry on any more without seeking help. I talked to the third assistant director and made sure the crew didn’t need anything urgently that Les and the standby prop man couldn’t deal with, climbed back down the ladder and told the launch driver to take me back to the mainland jetty. We landed and I staggered my way into the shack that was an imitation of a local shop. They had no water; the only liquid available was a can of terrible vegetable juice and, being desperate, I took it and drank it. It made me more nauseous and thirsty. Somehow I drove home feeling quite delirious. Arriving at our house I grabbed some water, drank copiously and, feeling really faint, collapsed on my bed.

Next thing I knew there were scorpions climbing all over the ceiling and the walls. I saw Les standing over me, talking to me, trying to make sense of what I was saying. I was telling him to remove the scorpions and kill them all, and could not understand why he kept asking me what I wanted. Why couldn’t he see them? Les told me later that at that moment he thought to himself, this is bad! He explained he was taking me in to the local hospital. It was more like a small clinic and had only about six beds.

I remember trying to answer questions that the doctor asked as he examined me and took blood samples. He took my blood pressure and looked at me seriously, as if the end was nigh! Suddenly I was whisked into a room at the back, which was the equivalent of a ward. I think they moved the patient out who was in there before me, as the bed was still bloodstained. But I really couldn’t care by this time where I was or what condition the room was in; I felt like I was about to die. I had relinquished all control over my situation.

I was lying down pondering my fate, passing in and out of consciousness, when a nurse came to see me. I had noticed on the wall next to the bed was a poster of Scotland, which I stared at in slight bewilderment as it seemed so incongruous in this Mexican hospital. I stared at it whilst drip feeds were attached to my arm and needles plunged into various body parts, including my backside. No one spoke a word of English, so I couldn’t ask any questions or get any information. I looked again at the poster; it was a stunning vista of the lochs in autumnal colors.

The nurse hooked up an IV drip and then, taking my arm, searched for a suitable vein to attach it to. She pushed the needle into me, hooked up the plastic line and left. My reverie was broken when the door opened and the nurse came back holding an enormous syringe. She silently proceeded to stick the needle into my artery, a really painful procedure. She looked down at me, talking in Spanish, trying to get me to comprehend her flood of unintelligible words. I could speak basic words, count, order food and find my way to the bathroom, but this stream of obvious questions was unfathomable to me. She kept pointing to the syringe full of thick white liquid she was forcing into my tiny vein. I looked confused and could not respond, so she continued to inject. The pain was excruciating. It felt like she was ramming concrete into my arteries. I was grimacing, while she kept taking my silence as a sign that all was fine. So I just stared at the poster and tried to visualize away the pain. Tough one that, though, when it feels like enough concrete to lay the foundations of a house is being pumped into an artery that is way too small to take the thick sludge. She just kept slowly but persistently pumping it into me, and my eyes were watering in pain.

Finally, after an age, it was over. She had had to do it really slowly for obvious reasons. She tapped my arm, pulled out the needle, re-attached the drip feed, and left.

It was then that I noticed the air bubble. It was trapped in the clear plastic tube carrying whatever liquid was being added to my blood by transfusion. It was near the bottle of liquid hanging on the metal arm and making its way slowly down towards my vein. Now I don’t know about you, but I have always lived with the belief that if an air bubble enters the bloodstream— that’s it, curtains!

I was feeling so ill and weak at this time, the fever was clouding my thoughts somewhat, and I started to think that maybe this was an omen. The mind goes into a different state when the body is closing down and is near the point when the vital organs lose enough chi or fire to keep functioning. I must have been very near that point because it didn’t seem such a bad option. It was all so surreal. I watched that bubble as it silently made its way down the transparent tube. In my confused mind was the thought that when that bubble entered my vein, all this feeling of nausea and weakness would finally be over.

The bubble inched its way down the tube towards my arm at a snail’s pace. Should I call for help or let destiny decide? I listened but there was no sound of nurses. I called out once but there was silence and the humming of the air conditioning. I was alone. This tiny innocuous bubble got nearer and nearer to the needle stuck in my arm where the tube entered. Everything in the universe came down to this moment. Nothing else had any consequence whatsoever. I do remember my past flashing before my eyes, thinking about moments that came back to me like fragments in time.

I looked again at the poster of the loch in Scotland, where I later filmed Black Angel. Something deeply connected there, somewhere at the bottom of the well of my subconscious, where the heart of spirituality lies. Looking at that picture and thinking of Scotland somehow made a connection to an inner knowledge. A resolve to live kicked back in with a force that surprised me. I made a vow to myself that dying here in Mexico on this movie was not an option—I had too much to live for. I became determined to fight this and get well.

The bubble had now reached about three inches from my arm. Suddenly the door opened, and the nurse walked in. That brought my instinct for life into full adrenal-punching force. I sat up and pointed to the bubble, exclaiming loudly in English, “LOOK!” The nurse did indeed look, laughed, and turned the valve on the drip feed line. The bubble shot like a Ferrari straight into my arm.

I stared wide-eyed and waited for my heart to explode. She was laughing at me and explaining something in Spanish. Nothing happened. My heart stayed beating, very slowly because of my weakness, but soundly beating, so I just lay back and tried to sleep. Apparently it was not my time to go, and a peace descended over me.

Les came to visit the next day with our Mexican interpreter. He explained that the doctor had told him I was very sick and that I’d be there a few days. Les and I had planned to go back to Los Angeles on the way home once shooting was over. We could still do that, depending on my recovery time. Les had called John Barry in Mexico City, who was very concerned and was monitoring the situation. I got the nurse in and asked the translator to ask about the injections. What she had been trying to tell me was if the pain was too much, to say so, and she’d stop and slow down. Ah, the bonus of being able to speak several languages!

They explained that it was a serious infection that could have affected my liver and kidneys, but they thought that because my system was strong, once they had killed the infection I’d recover one hundred percent. I was also chronically dehydrated from the illness, and they were pumping vitamins into me. The shoot was winding down fast so I wasn’t missing much. Les had only a few days left to supervise.

I was alone the next day when a production assistant came to see me. He had a proposal from the film’s line producer, Arthur Carroll, to put me on the next plane to London, without enquiring as to my medical condition and if I was able to fly over fourteen hours. For that offer he needed me to sign a contract that stated that they had no more responsibility for me. He had presumed that the carrot of putting me on the plane home was the thing I most wanted in the world and that I would just say yes.

Of course I would be well looked after in hospital in Britain, but Carroll had not bothered to come to see me, or inquired how I could travel. The doctors thought that a fourteen- to sixteen-hour plane ride in my condition could have dire consequences.

Even in my weakened condition I refused to sign anything. I knew instinctively that despite this being such a poor facility, it’s always best to get treated locally when it’s an infection in the stomach or intestines, as they generally know what to do faster than a hospital in London would.

Maybe Carroll presumed that we all felt like him and were desperate to get home to the green hills of safe old Blighty. John Barry had found out the situation and really torn a strip out of Carroll. John had realized very fast what had happened. When someone is sick they are automatically covered under a movie’s insurance policies. John had told them that I should stay in the Mexican hospital until they said I was able to travel and then be put in a hospital in Los Angeles, where we were ticketed home from anyway, to get full clearance before being allowed to go on. John had realized they didn’t want to bother filling out all the forms at such a late stage of the production.

I was finally told I could leave the hospital and would be sent to Los Angeles, to a hospital in Santa Monica where I would be cleared. I had not been able to enjoy the last days and say goodbye to all the friends I had made there. I did see Rudy and gave him my leather briefcase that he had coveted and a load of unused per diems. Movie crews become like extended families; we work under such stress and heavy workloads that barriers come down and people bond really quickly. I loved Mexico. The people were so generous, filled with warmth and romance, and a true love of life.

I was told in the hospital in Santa Monica that the doctor in Guaymas had in fact cured me, and they confirmed I had had paratyphoid. After a week of recuperation I was discharged to the hotel. Les and I were told to meet John Barry the next day before he flew home. Driving up the coast to Malibu to meet him for lunch was a glorious drive.

I pulled into the parking lot at the end of the Malibu pier, and here stood the famous Alice’s Restaurant named after the Arlo Guthrie song and movie. Painted white with large blue letters saying Alice’s it stood out from the rest of the landmarks there. Built right at the end of the pier it was famous for its all-round views of the ocean, for its seafood and a special cocktail called a B52. It was a known hangout for the in-crowd of the day who would spend a lunch or dinner at the restaurant and then hang out on the beach watching the surfers. This was in the sixties and seventies, the era of the Beach Boys, and Malibu was the Mecca. We parked right next to the Spanish buildings at the roadside end of the pier that used to be a fishing-equipment shop and walked down the wooden planks of the pier to the restaurant. We entered through their famous stained-glass door.

We met John and talked a great deal about Lucky Lady and our experiences. We had not seen each other since John had left Guaymas for Mexico City with the first unit, so we had a lot of war stories to recount. Then John made the auspicious announcement: George Lucas had officially asked us to start work in London in August. I was confirmed as set decorator and John said that the budget would be really tight for this type of movie and we only had seven months to prep it, which was just doable if we got everything planned with George in the coming months. The robots and other planned scenes would take the most time. Just the three of us would be working on it at first, as Norman Reynolds had gone back to the UK onto another film.

John had planned that we were to spend the next weeks alone with George to work out the logistics of making the film. This was going to be a challenge. The present budget he had discussed with Gary and George and Fox meant that the sets and construction and dressing and art department costs were well under a million dollars. This would be incredibly tight for the envisioned world we had to create. John told us about the movie, George’s aspirations, and what the basic story and premise was. We knew George had liked our sets on Lucky Lady. He was determined to make Star Wars look as if we had filmed on old locations and create ships as if they existed and were used and real. This was my dream, the way I always wanted to see science-fiction movies made. We celebrated and John told me to rest up and be ready for work in August.

Les and I drove back down the coast and back to the hotel to arrange our own flights home. I was ecstatic—to have another movie with John Barry to go straight onto was obviously a good thing, but to have one that was in a genre that I loved and which were rarely made in Britain was a rare gift. For me that lunch in Alice’s Restaurant, now long vanished into local history, is engraved in my memory forever as a truly auspicious moment, a defining moment in my destiny. I was pulling my Excalibur out of the rock and envisaging Luke choosing his as he watched the twin suns of Tatooine…

STAR WARS

Back in the UK, John, Les, and I were called to Soho Square for a meeting with Peter Beale, the managing director of Twentieth Century Fox in the UK. Peter explained that the budget was really tight. He said that they would allocate around four million dollars to make the film with, so the entire art department budget was just under a million. The budget had come out at eight million dollars to make the movie in America, and Peter had persuaded them that we could make the same film in the UK for half that. So our job now was to prepare a budget for the art department and make it work. We left knowing we had a lot of work to do and a great deal of alternative thinking to make this possible. Time was also short as shooting was destined for March the following year.

Robert Watts was employed as the British line producer to pull the production together for Gary and George. An experienced and wonderfully calm man at the head of a seemingly impossible task, he ended up staying with the team as a producer through the first three movies. Robert and John Barry hired a few rooms for the art department and a small stage at Lee Studios in Kensal Rise, West London. This was a tiny studio owned by Lee Electrics, who were the largest cinema lighting and electrical hire company in the UK. I had worked there several times, including on Ken Russell’s movie Mahler, which I art-directed; we made all the sets and studio shooting there. Ken Russell liked the studios as they were just a mile from his house, and he also made some of The Who’s rock opera Tommy there. I made a commercial with David Lean’s DP Freddie Young, building a Kensington-style house and garden in the main studio that was famous for its central pillar, which we all had to design around. I turned it into an apple tree on that one.

I signed my letter of agreement for Star Wars for the princely sum of one hundred and fifty pounds a week. This was a lower salary than normal, but George Lucas was paying us from his own pocket, and I personally wanted his film to be made. It was a chance to be innovative, and I had ideas brewing in my mind about how to create a revolutionary look for the props and dressing. The money was irrelevant.

I was given a copy of the script to read and had to swear on my life that it was for my eyes only—it was so secret. It was titled Journal of the Whills by George Lucas. In fact very few people ever got a script—even the actors only got pages to read—but as set decorator I had to break down every scene and list out every prop and weapon required, and also work out all the dressings needed for each environment. I read the script through quickly to get a sense of the story and atmosphere first, before going back again to study it in detail. I liked it enormously. I immediately connected with it because it felt so familiar, reminding me of the great myths and legends I had grown up with, but set in a totally new way in space. It was full of action and drama and was essentially a Western in space with mythic heroes, good against bad, evil against the forces of light. The lightsabers stood out as an amazing invention and a natural evolution, bringing ancient sword-fighting heroes into a science-fiction setting.

George and Gary came over to work with us and go through aspects of the design and feel for the film. He confirmed that he wanted everything natural and real and made as if it were practical, just as he had outlined to me and John in Mexico. The dusty Western feel he had seen in the sets we had created in Guaymas was a reference point. He wanted nothing that would stand out as being specially made for a science-fiction film, no sets or props should ever be conspicuous as sets or objects designed to attract attention. Hallelujah! I smiled inside; this was music to my ears as this had always been my philosophy. I hated the older science-fiction films where everything looked ‘science fiction’.

George had a few paintings by the brilliant concept artist Ralph McQuarrie to show us. Ralph had painted characters and settings, which had been developed whilst George was working on the script. These became our reference point to rely on to create George’s vision. R2-D2 was there as a design and character, and C-3PO, a sophisticated droid who carried the story along with R2-D2 on many adventures. They were integral to the movie working, and we had to think of a way to make them real. Also in another painting were Luke and his landspeeder, and other details of the Death Star and characters. Ralph was the unsung hero behind George, creating paintings to illustrate Star Wars as George envisioned it. We talked about Silent Running and how Douglas Trumbull had built his robots around amputees, and of course we talked about Fritz Lang’s great German masterpiece Metropolis, unbelievably released in 1927 Klein-Rogge’s golden robot inspired our belief that a character could work as a robot if we developed R2-D2 around the right actor. With our small budget and time for preparation pretty tight at this stage, it was agreed that to make R2-D2 work, we would need to experiment with the possibility of building it around a very small person. We were all thinking on the same page.

George had asked Ralph McQuarrie to design C-3PO and R2-D2 to his exact specifications as he worked on the script. The actual inspiration for these two bickering characters came from one of my favorite Kurosawa movies, the wonderful Hidden Fortress. George liked the idea of the story being told by the two lowliest characters, and their bickering and arguing made the adventure funny in places and supplied the glue to connect the action and the drama.

Kurosawa has been a major influence on so many filmmakers; he was considered the master by most filmmakers before Star Wars came along. Now everyone I meet in the industry says it was Star Wars that changed their lives and made them pursue their goals of working in film. When I wrote and directed Black Angel, I was influenced by Kurosawa and the idea of the lone samurai. Ideas feed on ideas with artists, and reinterpretations create new and fresh art. C-3PO had one thing in common with the central robot in Metropolis: the costume had to fit tightly to an actor. However, we had to create our own iconic character. For us the two robots were the most complicated task in the short timeframe before shooting the following March. George had created interesting robot police for THX 1138, so we had his confidence in exploring these ideas. Fortunately for us he had seen the results work using the same techniques with a very low budget already.

Reading the script I recognized the deeply embedded homage to myth and the philosophy of the power of legend, where good triumphs over evil. I reread it several times and then set about doing the very accurate breakdowns I always made, listing everything in the script relating to my task as set decorator and anything I could think of that I needed for dressings. Robert Watts was there with John Barry preparing the budgets with Gary. We took George to Julie’s Restaurant in Portland Road on the first day he was there. This restaurant served as our canteen from then on, as he liked it so much. It was one of my favorite restaurants, just off Ladbroke Grove. The restaurant was laid out in individual rooms, each one with its own décor and style. The owner, Julie Hodgess, had found the building and decorated it with an eclectic mix of found bric-a-brac, objects, and furniture. Julie was one of the designers of the famed and legendary fashion house Biba on Kensington High Street. Julie’s had beautiful eclectic furnishings like an eastern restaurant. We sat this first day on a richly covered tapestry sofa with a low carved Moroccan coffee table in the middle to eat from, and deep velvet armchairs the other side to sink into. Moroccan lamps hung from the decorated ceilings. George appreciated the atmosphere; it was clearly an influence on our thinking in a way. Not sitting stiffly at a white cloth-covered table in a classical restaurant but in the rather more exotic and bohemian atmosphere the owner had created was certainly more in harmony with our discussions of the muted look of the movie. Julie’s has survived and is as trendy as ever, having played host since those early days to so many celebrities, actors, and rock stars, still proving a great place to hang out and relax. Little has changed it seems, from the photographs. I guess it should warrant a small blue plaque now for hosting such auspicious guests for so many months.

Every lunchtime we spoke in detail about the movie and used this time to focus our attention on getting the feel for it exactly right. These early discussions with George and Gary were imperative in getting the world he envisioned unified into our minds. George had spent a lot of time developing the universe, working with Ralph McQuarrie on illustrating the characters and costumes and the look. R2-D2 and C-3PO were the key to this universe and the first characters we see in Star Wars (along with Darth Vader). They were the Laurel and Hardy of the movie, whose humor and banter told the story for the audience to key into. Getting these characters right when there were limited special effects in those days was key to the movie being fully realized. So we had to make them work, and create their personalities through their visual appearance. Then there were the sets and the weapons and props. We spent hours and hours discussing it all, so that we were all playing the same violin as it were. Fortunately John Barry and I instinctively understood what George was after and that’s essential. I found to my own cost it is impossible to make someone understand, even with visual reference, if they do not get the genre and the rules and regulations one has to adhere to.

When we were creating the first of the trilogy of movies we were literally breaking new ground. We had nothing to fall back on, no prior visual references in any movies to create the worlds that Star Wars pioneered. It meant taking a huge leap of faith for George Lucas, John Barry, Les, and me. To find a visual language that we all understood, and all within the tiny budget allocated, seemed a daunting task in those early days.

John Barry stayed busy sketching out ideas for all the sets and trying to find ways with George to cut costs as Gary’s budget kept escalating above the eight million dollar mark. John Stears wasn’t working on the film at this stage but was doing budgets for Gary and Robert, and his special-effects budget kept ballooning way up. It was made clear to us that Twentieth Century Fox wouldn’t commit until the budget was locked and proven, and as George was paying us from his own pocket the pressure was very much focused on our small team.

Instinctively, I knew I could not set-dress this film conventionally. The budget was simply not there to do it that way, and also on my mind was how to achieve the gritty documentary look required for the interiors and exteriors of the ships and sets. We needed to make it as if we had just gone on location and found a spacecraft that was well used and worn for the Millennium Falcon, and had rented it for the filming. How to achieve what I had been extolling to George for this look was causing me a lot of angst. Fortunately, George had had the experience of making an experimental science-fiction movie with THX 1138. He had created a science-fiction world in real locations with a very limited budget, so he was instinctively able to understand what we had to achieve and what we were up against. This made our small team of five people, comprising John, Les, me, George, and Gary, feel like a small band of unified cinema revolutionaries.

I finished my breakdown of the script, which had taken a few days as it was highly extensive. I first grouped all the scenes in the same settings together. Then, to imagine what the interior or location scenes would look like, I talked with George and John Barry, and carefully studied the sketches of Ralph McQuarrie and John.

On a normal modern-day or period film my breakdown becomes a list of the furniture and dressings that will make the set real. This also includes anything specifically written into the scene, like the owner smashing up the room in anger, or cooks creating a meal in a kitchen, for example. We list out tables and chairs and curtains, carpets, and the main dressings. Then I list out any objects or props utilized in the script, and also anything else I think of that they might need. There may be an object in the next scene or later on in the film that has to be seen for the plot. There is a separate list for weapons, so all guns, knives, sticks—whatever is required—are listed. Animals are another category and vehicles yet another.

On a science-fiction movie there are no reference points to go to, as it is all in the imaginations of the writer and director. All we had to visualize at the start were the few paintings in which Ralph McQuarrie had so beautifully illustrated George’s imagination. There were really no reference points as most of the science-fiction movies that had been made were not as oily and real as George envisioned. I had to try to imagine what the interior of Obi-Wan Kenobi’s hideaway in the desert would be like, first described in this draft of the script as a much larger complex than the eventual budget cuts would reduce it down to. I had to imagine the contrasting interiors of the specially built Death Star to the used and battered Millennium Falcon, and the various exteriors and interiors on Tatooine. One set in particular stood out, the Cantina, and another got me wondering how to dress and make real the garbage compactor.

I stared at my comprehensive list of what was required and tried to estimate the budget to make it all. I had to find a solution to pull this off. When I looked at my list of weapons required as well, my heart sank. All the principals had guns, or lightsabers for the Jedi Knights, including Obi-Wan. The stormtrooper army alone amounted to nigh-on a hundred weapons. There were the Tusken Raiders and Chewbacca, and of course Darth Vader and his consorts. My budget would never allow for all this if we designed and built them all from scratch. Then there were robots—not just R2-D2 and C-3PO, but all the ones for sale by the Jawas and a load more for the interior of the Sandcrawler, which stood out, filled with junk robots and machinery. Then there were the vehicles like Luke’s landspeeder and others outside the Cantina, and various animals too. The Millennium Falcon was to be the most densely dressed of the ships judging by the descriptions from George, especially as it was old and banged up. The Death Star had a lot of built-in dressings as it was much cleaner and more 2001-like, but had areas to create within it like the garbage-disposal room and Darth Vader’s conference room.

Then there were all the desert scenes in Tatooine. I knew John was thinking of Morocco or Tunisia for the locations, as both have sand dunes and amazing architectural oddities from the past that are well preserved. I knew Morocco well, having been there many times. I was pondering things like Luke’s homestead with his aunt and uncle—as there were domestic scenes written in, like having a meal with blue milk, what would they be eating? There were various scenes around the Sandcrawler and the moisture-collection devices in the desert. The exterior of the Cantina was described as being in the locale of a small township with markets where they went to buy spares for the ship. There was a crashed spaceship described in the script right behind the Cantina entrance. That one gave me food for thought! All of this would require a lot of imagination to create.

I guess I was lucky in that my sensibility towards movies, especially science-fiction ones, was reality-based. I wanted to see environments that were lived in and real, so that I could finally connect to a science-fiction world I believed in, and felt that an audience would, too. George mentioned Westerns a lot, and I understood what he meant. Of course we all loved the Spaghetti Westerns made by Sergio Leone, films like A Fistful of Dollars, inspired by Yojimbo, another in the collection of masterpieces by Akira Kurosawa. We weren’t making a Western but there’s a feeling in the look that especially relates to the first Star Wars, much more so than in the other films in the Star Wars series.

Once Upon a Time in the West