Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

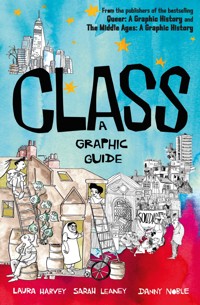

What do we mean by social class in the 21st century? University of Brighton sociologists Laura Harvey and Sarah Leaney and award-winning comics creator Danny Noble present an utterly unique, illustrated journey through the history, sociology and lived experience of class. What can class tell us about gentrification, precarious work, the role of elites in society, or access to education? How have thinkers explored class in the past, and how does it affect us today? How does class inform activism and change? Class: A Graphic Guide challenges simplistic and stigmatising ideas about working-class people, discusses colonialist roots of class systems, and looks at how class intersects with race, sexuality, gender, disability and age. From the publishers of the bestselling Queer: A Graphic History, this is a vibrant, enjoyable introduction for students, community workers, activists and anyone who wants to understand how class functions in their own lives.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 105

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

INTRODUCING CLASS

Class can be found in many spheres of our lives, but it can be difficult to pin down. We often use other words and images to talk about class. When class is spoken about directly, it can have different meanings to different people. In this book, we will be thinking about class as:

an idea to describe inequalities in societya category based on our job or incomea group of people who are fighting for their rightsa struggle over poweran influence on our likes and dislikesa label shaping how we feel about ourselves and other people.4This book will introduce you to different ways of understanding class. We will explore a range of theories about what class is and the broad effects it has, and we’ll encourage you to think about class in your own life.

We hope to spark your interest, highlight examples of when class has been challenged and inspire you to think about how we can break down class inequality.

Thinking about class can help us to:

see how resources are unfairly distributedquestion stereotypesnotice and challenge unfairnessfind ways to stand up for each otherreflect on how our lives are connected to others’.5All theories of class are developed in specific historical and social contexts, so they reflect the world as seen through the authors’ eyes in that particular moment. Our own learning and research about class has been shaped by our social background. We have tried to disrupt dominant narratives of class by using critical perspectives to interrogate “classical” theories and our own ideas.

ROADMAP

We’ve written this book so that it can be dipped in and out of – you don’t need to read it cover to cover. The pages are grouped into these sections:

We finish by encouraging you to think about social class in your own life and suggest different ways you can take action to challenge class inequalities.

CHAPTER 1: HISTORIES OF CLASS

Concepts are not neutral – they are created in specific historical and social moments as tools to describe and explain the world. Concepts can also have an impact on the world – in organizing social life, justifying how things are and pointing to strategies for change. In the next few pages, we will consider how the concept of class has been used and how it has travelled through time and space.