16,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

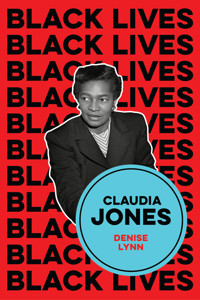

- Serie: Black Lives

- Sprache: Englisch

Activist, journalist, and visionary Claudia Jones was one of the most important advocates of emancipation in the twentieth century. Arguing for a socialist future and the total emancipation of working people, Jones’s legacy made an enduring mark on both sides of the Atlantic.

This ground-breaking biography traces Jones’s remarkable life and work, beginning with her immigration to the United States and culminating in her advocacy for the emancipation of the most oppressed. Denise Lynn reveals how Jones’s radicalism was forged through confronting American racism, and how her disillusionment led to a life committed to socialist liberation. But this activism came at a cost: Jones would be expelled from the US for being a communist. Deported to England, she took up the mantle of anti-colonial liberation movements.

Despite the innumerable obstacles in her way, Jones never wavered in her commitments. In her tireless resistance to capitalism, racism, and sexism, she envisioned an equitable future devoted to peace and humanity – a vision that we all must continue to fight for today.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 441

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Series Page

Title Page

Copyright

Acknowledgments

Introduction

The Long Life of Claudia Jones

Claudia Jones Today

Claudia Jones’s Life’s Work

Notes

1 Jones’s Early Years (1915–1936)

Trinidad and Tobago

United States

Notes

2 Communist Party, USA (1936–1946)

Joining the Party

Party Work

From Antifascism to Antiwar

Surveillance

Browderism

Notes

3 The Early Cold War (1945–1950)

US Fascism

The “Woman Question”

Arrest

Theoretical Corpus

Anticommunism and Racism

Notes

4 Anti-Cold War and Deportation (1950–1955)

Half the World

Arrest and Trial

Prison

Deportation

Notes

5 London (1955–1964)

Adjustment in England

CPGB

West Indian Gazette and Afro-Asian Caribbean News

Riots

Carnival

The Commonwealth Immigration Act

World Communism

Notes

Conclusion

Funeral

Manchanda and Jones’s Memory

Jones’s Legacy

Notes

Abbreviations

Index

End User License Agreement

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Series Page

Title Page

Copyright

Acknowledgments

Introduction

Begin Reading

Conclusion

Abbreviations

Index

End User License Agreement

Pages

ii

iii

iv

vi

vii

viii

ix

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

263

264

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

272

273

274

275

276

277

278

279

Black Lives series

Elvira Basevich, W. E. B. Du Bois

Denise Lynn, Claudia Jones

Utz McKnight, Frances E. W. Harper

Joshua Myers, Cedric Robinson

Claudia Jones

Visions of a Socialist America

Denise Lynn

polity

Copyright © Denise Lynn 2024

The right of Denise Lynn to be identified as Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

First published in 2024 by Polity Press

Polity Press65 Bridge StreetCambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press111 River StreetHoboken, NJ 07030, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-4932-0

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2023932869

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website:politybooks.com

Acknowledgments

I have admired Claudia Jones for over twenty years now. One of my first graduate school essays was on Jones back in 2001, before much of the great scholarship that has been written on her was produced. This book is part of my small contribution to the study of Jones’s life and activism. There is so much more to learn about her and there is a coterie of wonderful scholars who have contributed to this project and the larger understanding of Jones’s life. I owe a debt of thanks to those scholars including Carole Boyce Davies, Lydia Lindsey, Erik McDuffie, Dayo Gore, Cheryl Higashida, Ashley Farmer, Marika Sherwood, John Munro, Kennetta Hammond-Perry, Rochelle Rowe, Sarah Dunstan, Patricia Owens, and Bill Mullens. I have also been lucky enough to work closely with other Jones scholars including Charisse Burden-Stelly, Derefe Chavannes, and Zifeng Liu. They have all influenced my thinking on Jones and the radical Black Left, and their scholarship helped me to put together this book. I must single out Zifeng Liu as having been especially helpful with this project: as I took it on during the Covid-19 pandemic that shut down archives and the ability to travel, Zifeng shared with me some of his research on the West Indian Gazette and the Camden Sisters’ book on Jones.

The reference librarians at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture were immensely helpful. Though the center remained closed for much of the pandemic, they helped to get some of the material I was lacking from the Claudia Jones Memorial Collection. Archivists and librarians at the New York University Tamiment Library archives also helped to get material. After years of researching Jones, I realized that there were several holes in my knowledge which archivists and librarians helped to fill, including those at my institution’s library who secured microfilm of several communist newspapers. Librarians and archivists are the beating heart of the history profession and so much of my work is thanks to them!

Historian Keisha Blain deserves an enormous amount of thanks and praise; never have I met another scholar who promotes the work and careers of others as much as she does. I must thank her for recommending me to Polity Press for this project. She is also the reason my scholarship has become so visible in the last several years. As editor of Black Perspectives, Blain invited me to become a regular blogger, which put my work out to a larger audience and led to a plethora of invitations for projects.

I’m very thankful to the many people who I have collaborated with over the last few years on projects having nothing to do with Jones; my other scholarship has helped me to understand Jones’s life and the people she worked with, lived with, socialized with, and loved. Tony Pecinovsky has been a friend and collaborator on many projects, as has Phil Luke Sinitiere. Vernon Pedersen and the others in the Historians of American Communism (HOAC) have been good friends and colleagues and encouraged me to take on another big project, editorship of the American Communist History journal. I’m also thankful for the larger scholarly community at my home institution: the people I see every day and who I can chat with about scholarship, family, politics, and everything else. I’m especially thankful for Cacee Hoyer, Stella Ress, Anya King, Jason Hardgrave, Kelly Kaelin, Kristalyn Shefveland, Sukanya Gupta, Veronica Huggins, Sandy Davis, Brittney Westbrook, Mary Lyn Stoll, and many others.

My dear friends from graduate school are a constant presence and I’ve been lucky to have them in my life to keep me grounded in the tumult that is undergraduate instruction – Chocolate Pants (Greg Geddes), Smooch (Gaylynn Welch), Heg (Dee Gillespie), Plasticus (Melissa Wrisley), and Goaterella (Mary Weikum). There are others who remain nearby via social media – Shannon King, Jennifer Cubic, Marian Horan, Sarah Boyle, Melissa Madera, Gulhan Erkaya Balsoy, Meg Engle, and so many more who deserve to be named.

My family has always been partially the one I was born into and mostly the one that I made. Thank you to my parents Jack Lynn and Judi Lynn. My brother Dan, sister-in-law Angie, niece Megan, nephew Ryan, sister Corinne and her partner Erin are only a text away whenever I need something or when we just need a laugh, or, in the case of Erin, to find out what Jones’s medical records mean. Losing our dear cuzbro Andrew left a hole, but we remember him always for the love and laughter he gave and not the pain he suffered. My best friends Ang Reap and wife Jess Bacon-Reap, Danielle Copeland and Jess Amisial, Nicole and Steve Russell, Sue Wee and Mark Hickman are all part of my extended family. Adrian Gentle has been a supportive and caring partner for many years, putting up with me dragging him around the country for research or just a good hike. And of course, my darling daughter Cybele, who is fiercely independent, but always willing to take a trip, especially if I’m covering the bill.

I am grateful to David Horsley of the British Communist Party for arranging a meeting between Tionne Paris, Winston Pinder, and me, on a sunny afternoon in May 2022. An octogenarian, and a local social justice legend, Pinder had kindly agreed to answer our many questions about his memories of Jones. So much has been written about her political life, so it was her personal life we wanted to know about. But for Pinder, Jones was an activist first, always focused on her work, never glorifying herself and never taking credit for her sacrifices. He told us she was a great dancer who talked about her mother frequently, but that she was reticent to open up to people unless they were close friends, and even then, she didn’t focus on her troubles or worries, or linger on her poor health; she was wholly devoted to the emancipation of everyone. She was a person he admired and loved, who was taken too soon and who left behind hundreds of political allies and friends. For myself, it felt special to have a personal connection to someone who had known Jones and worked with her. I did not uncover everything I wanted to know about Jones for this project, but I nonetheless submit it as another humble contribution to what has already been written.

Introduction

For Claudia Jones

Just to tell you

that part of us

sailed on with you

To tell you

we’ll renew our planting

this bleak and mournful day

We’ll change the seasons,

the sun and moon

of man-made years

That soon

our tears will flower

into reason’s beauty

And our land

will call you home

to be its heart.1

Edith Segal

Claudia Jones was deported from the United States in 1955 because she was a Black radical communist. As the poem above indicates, she was a loved and respected leader admired by her friends and comrades. She was a devoted antiracist and anti-sexist who advocated peace, demilitarization, and anti-imperialism. She was a leading thinker in the American Communist Party (CPUSA) and a prolific writer whose comrades worked diligently to prevent her deportation. Jones was what US intelligence and legislative leaders deemed an enemy of the state and a national security risk. In violation of the constitution and the Bill of Rights, she was monitored, harassed, arrested, and eventually deported from a country she had spent most of her life in. She was sent far from her family, friends, and comrades to a country she had never lived in before, where she would stay for the remainder of her short life.

Jones was also deeply influential, well-known among both Black and white comrades for her acute theoretical grounding and her activism. She was loved by her family and friends, worked with progressives and liberals to improve the lives of women and people of color, and left a legacy for later Black radical feminists. She remained known and influential among a small group of activists and scholars who mined her written and spoken work and eventually resurrected her for a larger audience of activists. Above all, Jones was a committed communist who not only anticipated the consequences of US militarization and capitalism but also envisioned a socialist future, the eradication of monopoly capitalism, and the achievement of social justice for the oppressed. Her writing and activism continue to offer important lessons for contemporary audiences.

The Long Life of Claudia Jones

After her premature death in 1964, scholars and fellow communists kept her in remembrance. Some of her friends and comrades lived long lives after her and taught a younger generation of activists about her life and work. The US communist press regularly featured Jones in articles, and in 1968 a group called the Claudia Jones Club was created in Chicago to honor her legacy and continue her work to seek justice. In 1969 the communist Daily World honored Black history week (which would become Black history month in 1970) with an homage to Jones and her friends Pettis Perry, James Ford, and W.E.B. Du Bois. In 1974, CPUSA leader and Jones’s comrade Henry Winston noted in World Magazine that she “was a passionate voice for truth and justice.” That same year, Alva Buxenbaum, a leader in the CPUSA’s Women’s Commission, published an article in the Communist Party of Great Britain’s (CPGB) Daily World on US communist women and their struggles for women’s rights. She listed Jones as one of the CPUSA’s significant leaders.2

In 1981, the scholar and Party activist Angela Davis wrote about Jones in her book Women, Race, and Class, describing her as a leader and “symbol of struggle for Communist women” who had refuted the “usual malesupremacist stereotypes” about women and women’s roles. Jones, Davis argued, showed that Black women’s leadership had always been essential in people’s movements, and would take even her own progressive friends to task for failing to take women’s rights and women’s roles in the movement seriously. Most important, Jones believed that “socialism held the only promise of liberation for Black women.”3

In 1985, Buzz Johnson, a Tobago-born activist, compiled a book on Jones titled “I Think of My Mother”: Notes on the Life and Times of Claudia Jones. Published by his own Karia Press, Johnson’s book was put together with the help of Jones’s friends and comrades, including Donald Hines and Billy Strachan, who had worked with Jones in London. Johnson credited Jones’s long-time friend (and former romantic partner) Abhimanyu Manchanda for encouraging the project. It was the first book on Jones, and it included news clippings and speeches offering a history of her life in her own words. The same year, Johnson wrote an article commemorating what would have been Jones’s seventieth birthday. He noted that the importance of his book was that, in all the years since she had passed, no work had been done on the study of her life.4

Three years earlier, Buzz and his then partner Yvette Thomas had been involved in founding the Claudia Jones Organization (CJO), set up to address the needs of “African Caribbean women and children.” The organization, which still exists today, is based in East London and engages in community outreach and education. Buzz and Yvette’s son, Amandla Thomas-Johnson, has talked about Jones’s influence on his parents and many others, and how she remained an important presence in London even years after her death. He recalls that as a youth he attended CJO programs including a Saturday school and a summer school. Every year on Jones’s birthday the CJO would organize an event at her grave in Highgate cemetery, next to Karl Marx’s grave. The group would lay flowers and sing:

Oh Claudia Jones’s birthday, Aye Claudia Jones’s Birthday, Oh Claudia Jones’s Birthday, we celebrate it today.

To Claudia, that female conqueror, in England and America she was a freedom fighter.

The song was written by a Calypso musician to celebrate Jones’s life of activism and her commitment to the emancipation of all.5

That the first significant look at Jones’s life came out of a London publisher is not surprising, given that her legacy in England is linked to the popular Notting Hill Carnival and her work with London’s West Indian community. Though she spent most of her life in the United States, her memory was scarred by anticommunism, and the American friends she left behind still operated in its shadows. In 1987, another London group began its own project to document Jones’s life. The Camden Black Sisters (CBS) was founded in 1979 by Lee Kane and Yvonne Joseph as an educational and aid organization for Black women. The group sought to create their own space to discuss issues relevant to African/Caribbean women. CBS was based in Kentish town, where Jones had spent many of her London years, so the group decided to create a project to draw attention to her life and work. Jennifer Tyson, a CBS researcher, reached out to the CPUSA for information on Jones. In 1988, the group published Claudia Jones, 1915–1964: A Woman of Our Times. The book included a personal and political biography and aimed to bring Jones to a wider audience.6

Aside from Angela Davis’s earlier work, one of the first scholarly treatments of Jones came from Donna Langston, a professor at the University of Washington. Langston wrote that she first learned about Jones not in the US, where she was virtually unknown except among communists, but from attending a “cross-cultural Black women’s studies course” at the University of London. She was told that Jones was the Angela Davis of her time, likened by the actor, singer, and activist Paul Robeson to Sojourner Truth and Harriet Tubman. Langston attributed the silence around Jones in the United States to the narrowing of US political culture during the Cold War. Her name had been forgotten, while others like Robeson or Elizabeth Gurley Flynn were remembered. To remember Jones was to engage with the “history of fascism, sexism, classism, and racism.”7

In January 1989, Winsome Pinnock, a British playwright whose family was from Jamaica, debuted her play A Rock in the Water at London’s Chelsea Royal Court theater. Based on Jones’s life, the play was performed by the Royal Court Young People’s Theater. It told the story of Jones’s ejection from the US and her life in England fighting for the rights of Black Britons against “right-wing extremist groups.” Given her own years spent in youth theater, Jones would no doubt have appreciated the fact that young actors were playing the roles, but she likely would not have agreed with the description of fighting against “right-wing extremists” since she just as often criticized liberals for their tepid action on securing justice. The play is currently being adapted for film. That same year, Julie Whittaker from BBC Midlands contacted the CPUSA to gather information for a short documentary titled Claudia Jones: A Woman of Her Time, which was created with input from some of Jones’s American comrades, including James and Esther Cooper Jackson, Marvel Cooke, and Louise Weinstock. Both the BBC documentary and the play speak to how Jones’s life in England was more readily remembered outside of communist circles than was her life in the United States.8

In the early 1990s, scholar and activist Marika Sherwood was alarmed that so many of the leading West Indian and communist activists who had known Jones were passing. She decided to organize a symposium devoted to Jones’s life and work – thirty people responded and the symposium, held in 1996, was recorded. Sherwood decided to undertake further biographical research, and eventually published the symposium transcripts along with contributions from Jones’s friends and colleagues, Donald Hind and Colin Prescod, in 1999, under the title Claudia Jones: A Life in Exile. This was the most comprehensive biographical work to date focused on Jones’s life in London, and it brought her to the attention of an even larger audience. Sherwood later shared her research material with other scholars by depositing it at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem, New York, paving the way for work by a new generation of scholars.9

In the wake of Sherwood’s and Johnson’s groundbreaking studies, Jones began to appear more regularly in scholarship among historians of American communism and the Black Diaspora in the 1990s. The growing literature on the CPUSA had largely ignored women, especially Black women, but that now began to change. Toward the end of that decade, there were at least three dissertations that either focused on Jones’s life and work or included her in a study of radical Black women. In an article from 1998, Rebecca Hill discussed Jones’s work on women’s issues within the Party and her keen analysis of the need for different approaches to women’s oppression. Kate Weigand devoted a chapter of her 2001 book Red Feminism to Jones, examining her most significant and widely known written work, “An End to the Neglect of the Problems of the Negro Woman!” As Weigand explained, Jones was a far more significant presence within the Party than had previously been acknowledged. Not simply a leader, she had been an important thinker when it came to influencing the Party’s policy and practice. As Charisse Burden-Stelly notes, Weigand showed that Jones moved Black women “beyond narratives of victimhood,” revealing them to be “empowered, progressive, active, and desirable.” Weigand’s book and Hill’s article were important revisions in the largely male-dominated CPUSA histories.10

Jones’s name increasingly began to appear in scholarship on socialist feminism, the Caribbean, and the Black Freedom Struggle. She was included in the Encyclopedia of the American Left, with an essay written by Robin D.G. Kelley. Kelley also discussed Jones in his 2002 book Freedom Dreams, where he noted that Jones positioned Black women as the vanguard of liberation movements and had advanced the argument that “the overthrow of class and gender oppression” required the “abolition of racism.” John McClendon wrote an entry on Jones for the encyclopedia Notable Black American Women, arguing that she was committed to the Leninist notion of Democratic Centralism, which centered authority in the Party’s Central Committee but made room for the rank-and-file to debate and critique policy and theory – something Jones excelled at.11

There were, however, few scholarly analyses focused primarily on Jones, until 2007, when the most significant study on her life and work was published: Carole Boyce Davies’s Left of Karl Marx. The book, Boyce Davies noted, was not meant as a “traditional biography” but instead offered an analysis of Jones’s life, literature, and activism. While Jones had been written about in relation to communism, Black Nationalism, and feminism, Boyce Davies approached her as an individual thinker and writer whose influence on the movements she engaged in was widespread and significant. As Burden-Stelly argues, this study “made an invaluable conceptual contribution” in its discussion of “radical Black female subjectivity.” Boyce Davies positioned Jones as a “radical Black subject,” defined as someone who “resists the domination of systems, states, institutions, and organizations” that “maintain oppression, exclusion, exploitation, and docility.” The book brought Jones more attention and inspired new generations of scholars and activists to think about how to formulate a politics of liberation. Boyce Davies had also been in contact with Manchanda’s ex-wife, Diane Langford, who had carefully preserved Jones’s papers. Langford entrusted Boyce Davies to deliver the papers to the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, further increasing the material available to future scholars.12

Claudia Jones Today

The scholarship and activist groups that kept Jones in remembrance influenced later generations, but they also confronted misinterpretations of her legacy. In her lifetime Jones was a target of anticommunism, in the United States and also in Britain. Her memory has either been sanitized, as in England where she is primarily remembered as the founder of Carnival, or ignored entirely – as in the United States – because she was a committed communist, a member of the maligned CPUSA, and an outspoken revolutionary. In the US, anticommunism continues to be used as a tool to circumscribe social justice movements, with right-wing leaders like Donald Trump deploying it against even the most moderate proposals for social justice. But new generations have embraced Jones and her committed activism, and reject anticommunism as a tool of the elites. Jones advocated the destruction of capitalism and militarism, the dissolution of old and new empires, and the advent of a socialist United States. Today, in a period that has been described as late-stage capitalism, and at a time when corporations are literally and knowingly choosing to destroy the planet for profit, Jones’s work and activism remain relevant and have begun to resonate with young activists.

In recent years polls have shown that American and British youth have soured on capitalism. Several media outlets have attributed this to the Covid-19 pandemic and the political posturing of government officials who urge young people to stay in their low-paying jobs for the sake of the economy. But even before the pandemic, austerity measures had led to a serious decline in quality of life. Culture wars have obscured the economic ills of others, obfuscated the reality of material decline, and provided cover for devastating cuts to already limited social programs. Although there is an increased interest in socialism on the left of the political spectrum, the right has begun to appeal to young voters. In the absence of a viable political agenda, the right-wing has managed to draw in young white people with racism and rage, directing frustration away from capitalists toward people of color. White nationalists have used racism and white supremacy to deflect attention from capitalist devastation and ensure the perpetuation of economic policies that favor the wealthy.13 But more and more young people are growing disenchanted with capitalism as it continues to ravage people and the planet, and as policymakers of all political stripes focus on ensuring corporate profits. The rise of Black Lives Matter (BLM), an organization founded in 2013 by three young Black women – Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi – was fueled by youth disaffection with institutions that perpetuate oppression, in particular the criminal legal system. Jones would have celebrated BLM’s founding, given her commitment to Black women as leaders in resistance struggles. As Lydia Lindsey argues, there is a “traceable arch” between Jones and organizations like BLM that react to the “cycles” of racial capitalism, “nationalism and state-terror.” Jones’s intellectual and activist work was a “presage” of BLM in terms of how it engages with the Black radical and intellectual tradition and in its understandings of Black women’s oppression.14

More recently, in the summer of 2020 – with the combined exigencies of the Covid-19 pandemic and a public policy that favored corporate profits over public health – American and British youth took to the streets to express their frustrations. Following the police murder of George Floyd in May 2020, in Minneapolis, Minnesota, protestors came out in unprecedented numbers in both the US and the UK. Some of them demanded a reckoning with history and began tearing down monuments that represented empire and the use of slave labor for wealth accumulation. In July 2020, protestors in Bristol tore down a statue of the slave trader Edward Colston and threw it into the harbor. In the United States, long-contested Confederate statues were removed, and in other locations around the world statues and other racist symbols of empire and capitalism were taken down. In Antwerp, Belgium, for example, a statue of King Leopold was removed.15 Globally, many are growing disillusioned and angry with capitalism’s history of exploitation and destruction, and with the bleak future it offers.

Corporations have answered by trying to commodify socialist heroes like Jones. Corporate virtue signaling is notorious for using civil rights icons to sell products, the most recent example being Dodge Ram’s use of a Martin Luther King Jr. speech in one of its truck advertisements. These companies have tried to connect to a younger generation interested in social justice by using famous civil rights figures to link liberation to material accumulation, selling the message that emancipation can be found in personal wealth. Jones has not yet reached that type of notoriety, but on October 14, 2020 she was featured as a Google Doodle. The Doodle’s accompanying text commemorated Jones’s appearance on a British postal stamp in 2008, in a series on “Women of Distinction,” and nodded to her role in founding Carnival, but it provided a half history that only briefly mentioned the fact that she was a communist. As Amandla Thomas-Johnson has noted, the danger with such attempts to mainstream revolutionary figures is that they get “rolled into … various national projects,” their memories become “muted,” and their critiques become watered down and de-radicalized.16

In 2021, Marika Sherwood’s book on Jones was republished by Lawrence & Wishart. In her preface to the new edition, Lola Olufemi argued that although Jones is remembered, her radical politics – including her lifelong devotion to Marxist Leninism, and her commitment to the global liberation of the colonized – have been sanitized. The CPGB never wholly embraced Jones because she “challenged their failure to acknowledge the plight of colonial subjects.” Olufemi reasons that it is simpler for British communists to ignore Jones than to acknowledge that some of their own membership were racist. Her memory in Britain focuses on an apolitical depiction of her as the founder of Carnival, rather than as a committed liberationist who challenged the capitalist, imperialist state. Jones did not found Carnival as just a celebration – it was a response to white supremacist violence that targeted London’s West Indian community. Jones also used it to introduce white Londoners to Caribbean culture, celebrate Black beauty, and radicalize the oppressed to stand up for their communities. Olufemi notes that Jones’s lifelong struggle with her health is also an essential part of her memory. She operated in a world that was “determined to kill her,” and which took her life as she became a leading figure in global liberation movements. What could have been we will never know, because she lived in a world that operated (and continues to operate) to kill “prematurely” those who threaten the social order.17

While the remembrance of Jones in Britain contains important elisions, in the United States her memory remained in anticommunism’s shadow. She and her generation have, at best, been marginalized in the history of the Black Freedom Struggle or, at worst, been seen as radical agitators, treasonous in intent and practice. Activists in the US and UK have found other ways to commemorate her. In 2008, a blue plaque was unveiled in Notting Hill remembering Jones for her role in the Carnival celebration. The plaque was the work of the Nubian Jak Community Trust, an organization devoted to commemorating the significant impact of Black Britons; its unveiling, organized by the Carnival committee, was attended by the High Commissioner for Trinidad and Tobago. In 2010, the filmmaker Nia Reynolds produced a fifty-minute documentary on Claudia Jones’s life titled Looking for Claudia Jones. English Heritage, a non-profit that manages historic sites, announced in 2023 that a blue plaque will be placed in Vauxhall, South London at one of Jones’s former residences. The go-ahead for the plaque was secured by an activist, as a commemoration of Jones’s life, influence, and activism during her London years.18

In 2020, Steve McQueen, son of a Grenadian mother and Trinidadian father, featured Jones in an episode of Small Axe, a series of five films that takes its name from a proverb: “If you are the big tree, we are the small axe.” The films aired on the BBC in the UK and on Amazon Prime in the United States, and showed the challenges faced by Black Britons from the 1960s to the 1980s. McQueen said that the series was meant as both entertainment and education. He noted that most people do not know who Claudia Jones is, but hoped that after watching the episode they “will go out and find out.”19

In the United States, the Claudia Jones School for Political Education, based in Washington, DC, has taken inspiration from Jones. The organization is devoted to political causes like labor organizing as well as educating the public on Jones’s life and work. It maintains an online archive of some of her most significant publications and invites scholars and activists to discuss her influence, her work and the work of her comrades, and her continuing relevance to contemporary struggles. The group is also partnered with other activist organizations focused on anti-imperialist and antipoverty struggles that continue to plague the US and the former colonies. It is an organization that takes Jones’s anti-racism, anti-sexism, anti-imperialism, and peace activism as a foundation for its own work.

Claudia Jones’s Life’s Work

Coupled with the growing research into her life, scholars and activists have looked to Jones as a model for how to face some of the myriad challenges in the twenty-first century. Her ideas were foundational in the Black Freedom Struggle, but are also useful in contemplating the problems she faced and that continue to exist. As an influential communist, immigrant, and women’s rights advocate, her life’s work focused on theorizing an emancipatory ethos that centered the most exploited. Jones’s contributions to freedom struggles include her criticisms of the fascist policy manifested in militarism and policing, her focus on the threat of monopoly capitalism and its role in the oppression of people of color, women, the colonized, and the working masses, and her insistence that the most oppressed (Black women) should take the reins in liberation struggles. She argued that by recognizing the most oppressed and working toward their liberation we could ultimately achieve the liberation of all people.

Above all, Jones was a Marxist. She offered a prescient and still relevant critique of monopoly capitalism. It was capitalists who benefited from war, poverty, racism, and sexism. Oppression was not a byproduct of capitalism; rather, capitalism thrived on and required oppression. Capitalists operated with the state to ensure profit at the expense of any real commitment to democracy. Jones believed that only with the destruction of capitalism could liberation be achieved. She did not, however, limit herself to traditional Marxist thought. Jones believed that Marxism fell short in its understanding of both racism and sexism. A class-only theory did not account for oppression within and among working people. In the United States, for example, class status was linked to race and gender, and the most exploited workers were Black women handicapped by racism, sexism, and class oppression. As Lola Olufemi has noted, Jones pointed to “race as a modality in which class is lived.” The white working class were often collaborators with capitalism, and even among left-progressives racism and sexism meant that white activists did not see people of color as their peers. Women were also excluded and marginalized in the labor movement. This viewpoint remains a challenge today, as some on the left continue to mute how sexism and racism operate with class oppression.20

Focusing on Black women’s triple oppression, Jones argued that they represented the most oppressed and exploited group. She believed that in order to secure emancipation, Black women had to take the lead among the global proletariat. Much of Jones’s written work took her fellow communists and left-progressives to task for ignoring Black women. What progress could anyone hope to make by ignoring the most exploited? Organizing workers for their liberation meant organizing ALL workers – including domestics, housekeepers, childcare workers, teachers, etc. In this way Jones helped to redefine labor in the Marxist cosmology: while the male shopfloor worker was important, Black women’s leadership, she argued, would be central to the liberation movement. Jones also believed that labor unions were important tools in cultivating class solidarity. Today labor unions have been defanged and are beholden to the goodwill of political parties. This process began during Jones’s lifetime as the unions fell prey to internal and external redbaiting. But Jones was convinced that interracial cooperation among workers would succeed in usurping corporate power. The same youth who have soured on capitalism today have begun leading unionization efforts across the United States and Britain in a united front against capitalist power.

Jones was an internationalist, anti-imperialist, and anti-colonialist. She did not define liberation narrowly, restricting it within the confines of the Western nations; as a colonized citizen, she understood that imperialism and colonialism strengthened the capitalist states and impoverished the colonized. She worked with activists around the world to address the privations of colonialism and imperialist exploitation. In the post-World War II years, as liberation movements secured independence, she was wary of corporate and military power as imperialism began to take on a seemingly benign image. The formerly colonized found that independence left them beholden to the imperial might of their former colonizers, and to the growing military behemoth of the United States. Liberation, therefore, required peace and demilitarization.

Jones was a peace activist. Peace was more than just the absence of war; it meant destroying the institutions that perpetuated inequality. Jones was alarmed that the end of World War II was leading to an endless conflict between the Soviet Union and the United States. She believed that militarism and war harmed women and children the most and that the United States was creating a permanent war economy. During the Cold War, imperialism took the form of a corporate colonialism upheld by American militarism. War also operated as an excuse for the violation of civil liberties and the suppression of liberatory struggles. Any challenge to the status quo became treasonous during times of conflict, and in the militarized United States there was (is) no other time but wartime. Jones saw what the United States would become – a country in a forever war focused on policing the world, while the American people are left fighting over the leftovers.

Perhaps Jones’s most important quality was that she was not a pessimist – she did not lose hope in the face of what often felt like insurmountable barriers. She retained hope in the people, the colonized, the marginalized, and, just as important, their allies. She always believed it would be socialism that ushered in an equitable future. Activists today face the largest concentration of wealth in recent memory, neo-colonial extractive politics in the former colonies, and a climate crisis that remains largely unaddressed because capitalists are unwilling to forge a future in which the planet comes first. The military behemoth that Jones and her comrades predicted has evolved into the largest and most expensive military-industrial complex in the world, a complex that sustains US capitalism and continues the exploitation of postcolonial states. Jones’s life and work offer a path forward to understanding how to achieve an equitable future. Capitalism and freedom do not coexist, democratic institutions cannot be wedded to the marketplace, and freedom will not be gifted by politicians beholden to corporations. For Jones, only with the destruction of capitalist and militarist institutions and states can the people secure justice. She advocated that the path forward required socialism.

Notes

1.

Edith Segal, “For Claudia Jones,”

Daily Worker

, January 2, 1956, 6. Text appears courtesy of International Publishers.

2.

“Happy Birthday, One Year Old, Claudia Jones Club,”

People’s World

, July 19, 1969, 11; “Claudia Jones: Heroine from Harlem,”

World Magazine

, February 9, 1974, Box 113, Folder 49, Communist Party Papers, TL; “In Memoriam – Black Communists,”

Daily World

, February 15, 1969, M-9; Alva Buxenbaum, “USA: Wider Level of Struggle,”

Daily World

, 1974, Communist Party of Great Britain Papers, The National Archives, Kew, Richmond.

3.

Angela Davis,

Women, Race, and Class

(New York: Vintage Books, 1981), 168–9.

4.

Buzz Johnson,

“I Think of My Mother”: Notes on the Life and Times of Claudia Jones

(London: Karia Press, 1985); Margaret Busby and Nia Reynolds, “Obituary of Buzz Johnson,”

The Guardian

, March 5, 2014,

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2014/mar/05/buzz-johnson

; Buzz Johnson, “Black Woman’s Struggle,”

Morning Star

, February 21, 1985, Box 113, Folder 49, Communist Party Papers, TL.

5.

Claudia Jones Organization, “History,” at

https://www.claudiajones.org

; interview with Amandla Thomas-Johnson, February 9, 2023.

6.

Pauline de Soza, “Camden Black Sisters,” in

Companion to Contemporary Black British Culture

, ed. Alison Donnell (London: Routledge, 2002), 62; Jennifer Tyson to Comrades, June 9, 1987, Box 113, Folder 49, Communist Party Papers, TL; Jennifer Tyson and the Camden Black Sisters,

Claudia Jones, 1915–1964: A Woman of Our Times

(London: Spider Web, 1988).

7.

Donna Langston, “Claudia Jones: Valiant Fighter against Racism and Imperialism,” 1–3, Box 113, Folder 49, Communist Party Papers, TL; Donna Langston, “The Legacy of Claudia Jones,”

Nature, Society, and Thought

2:1 (1989), 76–96.

8.

Tim Gibney, “Poignant Story of a Fight for Rights,”

Kensington Post

, January 26, 1989, 15; “Profile: Claudia Jones,”

People’s Daily World

, February 13, 1988, Ron Johnson, “A Fighting Caribbean-American Leader,”

People’s Daily World

, February 10, 1989, Box 113, Folder 49, Communist Party Papers, TL.

9.

Marika Sherwood,

Claudia Jones: A Life in Exile

(London: Lawrence & Wishart, 1999). The book was reprinted in 2021 (

https://roarmag.org/essays/claudia-jones-olufemi

/).

10.

Rebecca Hill, “Fosterites and Feminists, Or 1950s Ultra-Leftists and the Invention of AmeriKKKa,”

New Left Review

228 (1998), 34; Kate Weigand,

Red Feminism: American Communism and the Making of Women’s Liberation

(Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001); Charisse Burden-Stelly, “Carole Boyce Davies and Claudia Jones: Radical Black Female Subjectivity, Mutual Comradeship, and Alternative Epistemology,”

Journal of the African Literature Association

(2022), 3, DOI: 10.1080/21674736.2022.2067740

11.

Robin D.G. Kelley,

Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination

(Boston: Beacon Press, 2002), 55; Burden-Stelly, “Carole Boyce Davies and Claudia Jones,” 3; John McClendon, “Claudia Jones,” in

Notable Black American Women

(Detroit: Gale Research, 2006), 343–6.

12.

Carole Boyce Davies,

Left of Karl Marx: The Political life of Black Communist Claudia Jones

(Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007), 1; Burden-Stelly, “Carole Boyce Davies and Claudia Jones,” 6.

13.

Julia Manchester, “Majority of Young Adults Hold Negative View of Capitalism: Poll,”

The Hill

, June 28, 2021,

https://thehill.com/homenews/campaign/560493-majority-of-young-adults-in-us-hold-negative-view-of-capitalism-poll

; Lydia Saad, “Socialism as Popular as Capitalism among Young Adults in US,”

Gallup

, November 25, 2019,

https://news.gallup.com/poll/268766/socialism-popular-capitalism-among-young-adults.aspx

; “Majority of Young Brits Want a Socialist System,” poli tics.co.uk, July 6, 2021,

https://www.politics.co.uk/news/2021/07/06/majority-of-young-brits-want-a-socialist-economic-system/

; Ellen Berry, “Austerity, That’s What I Know: The Making of a Young UK Socialist,”

New York Times

, February 24, 2019,

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/24/world/europe/britain-austerity-socialism.html

; Mona Chalabi, “Trump’s Angry White Men,”

The Guardian

, January 8, 2016,

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/jan/08/angry-white-men-love-donald-trump

.

14.

Lydia Lyndsey, “Black Lives Matter: Grace P. Campbell and Claudia Jones – An Analysis of the Negro Question, Self-Determination, Black Belt Thesis,”

Africology: Journal of Pan-African Studies

12:10 (2019), 110–11.

15.

“Black Lives Matter Might Be the Largest Movement in US History,”

Carr Center

, June 3, 2020,

https://carrcenter.hks.harvard.edu/news/black-lives-matter-may-be-largest-movement-us-history

; “How Statues Are Falling around the World,”

New York Times

, September 12, 2020,

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/24/us/confederate-statues-photos.html

,

16.

Graham Lanktree, “What MLK Said about Advertising after Dodge Criticized for Using His Words to Sell Trucks,”

Time

, February 5, 2018,

https://www.newsweek.com/martin-luther-king-advertising-dodge-super-bowl-799355

; interview with Amandla Thomas-Johnson, February 9, 2023.

17.

Lola Olufemi, “Claudia Jones: A Life in Search of the Communist Horizon,”

Roar

, September 25, 2021,

https://roarmag.org/essays/claudia-jones-olufemi/

.

18.

“Claudia Jones Blue Plaque Unveiled,”

Caribbean

, August 22, 2008,

https://www.itzcaribbean.com/uk/carnival-uk/claudia-jones-blue-plaque-unveiled/

As of this writing in 2022 the documentary was available to view on YouTube at

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VUMTOwrzgzs

; Harriet Sherwood, “Notting Hill Carnival’s ‘Founding Spirit’ to Be Honoured with Blue Plaque,”

The Guardian

, January 26, 2023,

https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2023/jan/26/claudia-jones-founding-spirit-notting-hill-carnival-blue-plaque-london-home-english-heritage

19.

Ellen E. Jones, “Small Axe: The Black British Culture behind Steve McQueen’s Stunning New Series,”

The Guardian

, November 14, 2020,

https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2020/nov/14/small-axe-the-black-british-culture-behind-steve-mcqueens-stunning-new-series

; Ben Travers, “Steve McQueen on 5 Integral Moments That Connect His ‘Small Axe’ Series,”

Indie Wire

, June 3, 2021,

https://www.indiewire.com/2021/06/small-axe-connections-series-steve-mcqueen-interview-1234641368/

20.

Olufemi, “Claudia Jones: A Life in Search of the Communist Horizon.”

1Jones’s Early Years (1915–1936)

Change the Mind of Man

Against the corruption of centuries

Of feudal, bourgeois, capitalist ideas

The fusion of courage and clarity

Of polemic against misleaders

Who sought compromise with the enemy

These were the pre-requisites of victory.

No idle dreamers these –

And yet they dared to dream

The dream long planned

Holds in socialist China.

From Yenan, cradle of the revolution;

Of their dreams, their fight

Their organization, their heroism

Yenan – proud monument to man’s will

To transform nature, and, so doing

Transform society, and man himself!

Claudia Jones1

It was a cold New York winter day when Claudia Cumberbatch and her three sisters and aunt landed in New York Harbor on February 9, 1924. Leaving their home in Port-of-Spain, Trinidad, where the average temperatures in February could reach 26 Celsius, Jones and her sisters faced a snowy, 1-degree winter day and an nighttime low of –10 degrees. Jones would later write that her parents had hoped the United States would provide them with economic opportunity and a welcoming place to raise their daughters. What they found instead was a country on the verge of an economic crisis, racial inequality, dangerous working conditions, and a constant struggle for survival. Trinidad, a British colony, faced poverty resulting from imperialist mandates; this, it turned out, was not unlike the Black experience in the United States, where official policy perpetuated racism and poverty.2

Jones’s parents, Charles and Minnie Cumberbatch, had arrived two years earlier hoping to settle in their new country, secure jobs, and bring their daughters to the US. Their fortunes were tied to the colonial economy, and a drop in the cocoa trade throughout the Caribbean led to economic turmoil and migration for thousands of West Indian families to the United States and elsewhere. Claudia’s arrival in the United States marked the beginning of her radicalization. The bleak conditions for Black Americans, and her own family’s experience with poverty and racism, were what made her a communist. She would draw on her youthful experiences in Harlem to inspire her critique of monopoly capitalism, her faith in Black women’s political leadership, and her commitment to socialism. As the poem quoted above shows, Jones became committed to changing the “minds of men,” getting them to recognize that emancipating the most oppressed would emancipate everyone.3

Trinidad and Tobago

Christopher Columbus landed on Trinidad in 1498, on his third trip to the Western Hemisphere; there he came upon the indigenous Arawak and Kalinago Indians. Columbus claimed the island for Spain, but the Spanish took nearly 100 years to settle it and the nearby Tobago island. In 1592, they created a capital named San José de Oruña in North Trinidad. In 1757 the governor moved to Port-of-Spain, followed by the Cabildo (town council) in 1787, making it the capital. In 1783, the Spanish and French created a plan to “develop Trinidad economically,” and they started by inviting white settlers into the area. By agreement, the French and Spanish encouraged primarily Catholic settlement. Settlers were drawn by offers of free land, and many of the French who came from surrounding islands brought enslaved people with them. They were also given additional land for each newly imported enslaved person. The Haitian revolution, which led to the displacement of French slaveholders, increased the island’s population.4 As scholars of racial capitalism have shown, the European industrial powers were founded on the racialized labor of the African diaspora. Racial capitalism, as defined by Charisse Burden-Stelly, refers to the “mutually constitutive nature of racialization and capitalism.” Hilary McD. Beckles argues that European interests in the Caribbean led to competition over control of the region’s resources and indigenous and enslaved labor. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the British, French, and Dutch attacked the Spanish colonial economy. Their goal was to “achieve maximum wealth extraction” in this new landscape. The Caribbean economy was deliberately created for a “singular purpose” as an “external economic engine” for “national economic growth.” As the European powers competed with one another to seize land and labor, they created an “immoral entrepreneurial order” that was “beyond the accountability of civilization.” Far away from their own legal and social orders, European settlers ushered in an era of extreme cruelty against the native and enslaved populations.5

As Trinidad and Tobago’s first Prime Minister Eric Williams explained in his book History of the People of Trinidad and Tobago, the Spanish were interested in little else but gold and silver. They forced the native population to work in mines looking for precious metals the islands did not have. In seeking to extract resources and labor from the indigenous populations, the Europeans were forced to negotiate as the native groups resisted the colonizers’ encroachment. What followed was a series of treaties that led to a “web of relations” between the indigenous, the Europeans, and the Africans. This web was an “entanglement” that led to “resistance and tension.”6 Williams argued that the Spanish obsession with gold meant that Trinidad and Tobago were left undeveloped, with the Spanish often shipping indigenous people to their other colonies for labor. When this exploitation thinned the indigenous population, enslaved people from Africa were forcibly brought to the islands. For a time, tobacco was the basis of the islands’ economy, until cocoa trees were planted. Once French planters arrived, they introduced sugar; there was also a healthy trade in coffee and cotton.7

In 1797, Spain “surrendered” Trinidad and Tobago to the British, though it was not formally ceded until 1802. Britain abolished the slave trade in 1807, which ended African importation into the islands, but slavery itself was not formally abolished until 1838. Even after abolition, Britain “worked hard” to maintain the “extractive model” it had developed in its colonial administration. Trinidad and Tobago joined other Caribbean islands in what was called the “British West Indies” (BWI), which formalized the islands as part of the British Empire. That name would be abandoned in the post-World War II period of decolonization, in favor of the “Commonwealth Caribbean.”8

Finding it difficult to secure a cheap labor force locally, sugar planters in Trinidad began importing Indian indentured servants, a practice that did not end until 1917. As McD. Beckles argues, the intention behind importing laborers was to “prolong wealth creation and appropriation” similar to slavery. What followed was a “long century of British colonial brutality” until rebellions across the Caribbean “discredited the colonial state.” But the British military ferociously suppressed the rebellions and engaged in massacres. Even as West Indians rose up against the colonial regime, “political oppression” was deployed to “maintain maximum wealth extraction.”9