Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

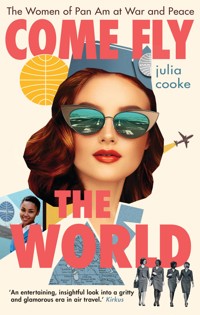

** Chosen as a May 2021 pick for The Fearless Book Club by Nobel Peace Prize–Winner, Malala Yousafzai ** Travel writer Julia Cooke's exhilarating portrait of Pan Am stewardesses in the Mad Men era. Glamour, danger, liberation: in the Jet Age, Pan Am offered young women the world. Come Fly the World tells the story of the stewardesses who served on the iconic Pan American Airways between 1966 and 1975 – and of the unseen diplomatic role they played on the world stage. Alongside the glamour was real danger, as they flew soldiers to and from Vietnam and staffed Operation Babylift – the dramatic evacuation of 2,000 children during the fall of Saigon. Cooke's storytelling weaves together the true stories of women like Lynne Totten, a science major who decided life in a lab was not for her, to Hazel Bowie, one of the relatively few African American stewardesses of the era, as they embraced the liberation of a jet-set life. In the process, Cooke shows how the sexualized coffee-tea-or-me stereotype was at odds with the importance of what they did, and with the freedom, power and sisterhood they achieved.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 425

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

iii

COME FLY THE WORLD

The Women of Pan Am at War and Peace

JULIA COOKE

v

For my father and the window seats he saved for me

xiii

Stewardess Wanted.

Must Want the World.

— pan am recruitment advertisement, 1967 xiv

CONTENTS

viii

ix

1968 Pan American World Airways Routes

LUCIDITY INFORMATION DESIGN, L.L.C.

x

xi

1968 Pan American World Airways Routes

LUCIDITY INFORMATION DESIGN, L.L.C.

PART I

THE WRONG KIND OF GIRL2

1

A Jet-Age Job

Lynne totten stood in the doorway for what felt like a very long time, looking at the women sitting in rows in front of her. Only minutes before, she had walked confidently down Park Avenue to the Pan Am Building, an octagonal skyscraper of broad-faceted glass and concrete. As Lynne approached the fifty-nine-story building’s shadow, she took in the enormous letters of the company’s name at its crown. She’d walked through the Pan Am lobby and taken the elevator up to the offices above as if she knew where she was going and what she was doing.

Now Lynne stood facing bouffants and elegant French twists. As she headed to the front of the room, she saw the faces of the women who wore them — perfect eye makeup. Lynne, short and dainty in her brown suede skirt suit, with long dark hair down her back — she had not thought to pull it up into a bun — considered the reality of where she stood, waiting to be interviewed for a job as a stewardess.

“How can you change a world you’ve never seen?” a Pan Am magazine ad read. This was the yearning that had sent Lynne to the interview. On television, the same campaign asked, “Why don’t you join the country club?” A golfer on a green field was quickly surrounded by people in varied international-looking clothing — men in the striped 4shirts of Italian vaporetto drivers or in baroque military jackets; women in Japanese yukata. “Big countries, small countries, old countries, new countries.”

But another Pan Am advertisement frequently aired in 1969 might have sent Lynne walking away just as quickly as she’d come: a gorgeous woman with flawlessly applied eye makeup brushing mascara onto her lashes and then striding down the street as the camera panned up from the sidewalk, taking in the stewardess’s perfectly cut blue suit, her tidy purse, her hair in precise waves under her hat. When Lynne considered how she must look to the assembled crowd of aspiring stewardesses, country bumpkin was the term that came to mind.

Lynne had grown up in Baldwinsville, thirteen miles outside of Syracuse, on the twisting Seneca River. In the summer, when the sun lit the streets long into evening, children came home only briefly for dinner, then went back out. Baldwinsville was an overgrown suburb with a quaint village of two- and three-story brick buildings, shade trees glowing orange and yellow on autumn afternoons, and church steeples of various Christian denominations rising above it all.

Until right now, Lynne had felt sure that this job was what she wanted. Her parents had worked hard to send her — the bright and promising student-body president of her small-town high school, obedient and optimistic — to college, the first one in their family to go. Lynne was grateful, but at college, her awareness of how lucky she was competed with a bone-deep disaffection for the lab work her biology major required. She was not always the only woman haunting the lab at the State University of New York at Oswego late into the night, but she rarely saw more than one other woman around. As far as she knew, she was the only female biology major in her year.

In the lab she barely glanced at the young men blending and separating compounds. Lynne paid strict attention to her own measurements; she harbored diffuse fears of blowing the building up. “Why are you here?” the men asked Lynne. It could have been intended as 5a compliment for a pretty woman under artificial lab lights, but the words had a hectoring edginess.

For Lynne, declaring a major was a promise, and she did not break her promises. She spent four years in class and in the lab and acquired two assistantships to keep herself afloat financially, including one working with soil samples for a palynology professor. Lynne was good at extracting hundred-year-old pollen from soil; it impressed her that pollen could not be destroyed and would always provide a map of the past. But beneath her commitment to her biology major, her gratitude to her parents, and her determination in the face of the subtle intimidation in the labs, Lynne had doubts. Sometimes she wondered what she was doing, what she was preparing for, especially as she learned about the world outside of upstate New York.

In Baldwinsville, around the dinner table on Sundays, when her parents closed the general store they owned to eat together as a family, international politics never came up. But at the coffee shops and diners in Oswego, Lynne’s peers debated government policy ardently. Combat in Vietnam escalated throughout Lynne’s undergraduate years and Lynne listened to her college boyfriend and his friends discussing the war. The first few times they challenged the decisions President Johnson and Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara were making in Washington, she felt uneasy. Who were they to question figures of authority? she asked.

They were male college seniors in the United States, they answered — their draft numbers and the end of their deferment upon graduation entitled them to question the government. Around the country and the world — in West Berlin, Sweden, Mexico City — students had begun to protest a war that, Lynne learned, had never been declared a war by Congress. Now she realized that covert American intervention in the region went back decades, to the Second World War and the decolonization that followed, separating Vietnam into north and south. Communism ruled in the USSR-allied north; a nominally democratic 6regime ruled in the south. American interest in the region centered on natural resources — Vietnam’s tin, tungsten, and rubber — and the fear of what President Eisenhower had called a decade earlier “the ‘falling domino’ principle.”

Between school and jobs, Lynne had little time to read newspapers. But she listened as her boyfriend honed his arguments, incorporating information gleaned from local and national newspapers and his political science coursework. He and his friends drained cup after stained coffee cup during heated debate. Two perspectives on the American troops that flooded into South Vietnam emerged. From one angle, American aid to the democratic half of a split Vietnam represented the nation’s commitment to helping the residents of a small, poor country resist a Communist insurgency. From another, deteriorating conditions in the south — antidemocratic elections, political arrests that kept prisons continually stuffed, a hampered press, corruption of the military and government, and deepening poverty — demonstrated the essentially imperialist nature of growing American intervention. As one semester led to the next, Lynne’s reluctance to second-guess national policy faded and grew into a conviction that she could do more in the real world than in a lab. In her scant free time, she glanced at the front pages of newspapers and magazines and saw names of countries she had never thought about before. There’s a whole world out there, she thought, and I need to get involved.

As she walked across the stage at graduation, her parents clapping proudly in the audience, Lynne felt a sinking sensation over the choices that had narrowed her life. She was qualified to work as a research assistant or a science teacher, or, as many of her peers had done already, she could marry. Lynne was still awed by the intricacies of the natural world but felt drained by the isolation and intimidation of the lab. She had the extroversion for teaching but she had already spent much of her life in classrooms. Marriage eventually, but certainly not now. Graduation was the worst day of her life.

But a professor had encouraged Lynne to sign up for a college-sponsored 7 painting course in Rome that summer, and she had taken out a small loan to pay for what her savings did not cover. A break from science coursework might be refreshing for her, the professor had said. For the first time in her life, Lynne was doing something for herself. She flew to Rome. The hot city was relatively empty, but the sepia-toned streets were alive with history. Lynne understood, after the heat and activity, why Italians slept in the afternoons.

The men in Italy were a trial. Like flies or bloodhounds, Lynne thought. “Bella, bellissima,” they whispered after her, though Lynne had never thought of herself as beautiful. She had to be downright rude to get rid of them. Once she retreated to the bathroom of a train station to avoid the men who harassed her.

Every day she took the bus from student housing on the outskirts of the city into Rome, going past the low outlying neighborhoods, winding through the tight old streets like a corkscrew. She would set up her easel on sidewalks. She had no talent for painting but that did not matter. She bought slides of the Vatican and Roman monuments to show her parents and snapped photographs of the “common things” that enchanted her: the shopkeepers and bartenders sitting on folding chairs in front of a trattoria with an ancient façade; Coca-Cola and Peroni logos on tin signs on the sides of markets; the women waving money toward piles of tomatoes and greens and citrus set atop fruit crates in the streets, red and green and lemon yellow against the old stone.

In Naples, Siena, and Florence, the alchemy of person, time, and place inspired not hesitation in Lynne but a growing certainty that the world was enormous and that she wanted to be out there, be in it.

In Baldwinsville, she told her parents about the plan she had hatched on her flight back to the States, and her mother was appalled. “You’re nuts,” she said. “We’ve just paid for four years of college.” Her elegant, disciplined, educated daughter was not a stewardess. Stewardess duties revolved around serving others. Airline press releases and recruiting advertisements evoked training schools focused on fashion, hostessing, and helping women acquire a “first-class husband.” 8Stewardesses were bound to be insipid, and Lynne was intelligent and serious.

Then Lynne’s father took her aside. After he had fought in the war, he’d traveled through Europe and Africa. He, too, was concerned about his daughter’s new goal, but he told her he would convince her mother if Lynne would agree to fly with Pan Am, the only American airline that flew exclusively international routes. He would accept no domestic airlines.

Lynne sent in her application and waited for her interview. At first she had not cared which airline she flew for; her only goals were not being in a lab and having a job that allowed her to experience different places.

She would have wanted to fly internationally eventually, she later realized. Her father had intuited her dreams more accurately than she.

Working as a stewardess gave a woman the ability to see different places — and also to experience who she could be against those varied backdrops. This invitation to try out an unfettered version of oneself somewhere else had appealed to enormous numbers of women from the start of the commercial airline industry. “Sadie in New York,” read a 1936 profile in the Chicago Sunday Tribune of a stewardess who had beaten out hundreds of other women for a spot on a United shuttle, “is a very different person from Sadie in Chicago.” In Chicago, Sadie Ericson lived “a life of considerable dash,” biking, swimming, roller-skating, and shopping. But twice a week, her job took her to New York, and New York Sadie was a different sort of woman. As soon as she arrived there, she bought two books — one fiction and one nonfiction — and a supply of magazines; she stocked her hotel room with a pound of chocolates and half a dozen apples and had her meals sent up as she read stretched across the hotel-room bed in her dressing gown.

A decade earlier, when air travel was raw and new, cabin attendants, in the established model of train stewards, had been men. But 9in 1930, a nurse and trained pilot approached an airline executive to convince him that nurses would make better cabin crew. The pitch worked. A nurse could more naturally reassure a fearful passenger, the executive wrote in a memo, or minister to airsick men. “The passengers relax,” reported an Atlantic Monthly writer. “If a mere girl isn’t worried, why should they be?”

In the mid-1930s, a stewardess had dragged two passengers from the burning wreckage of a Pennsylvania crash that killed twelve. Though she was injured herself, she ran four miles for help. Front-page articles celebrated her as a heroine. Profiles of other women and their crews, friendships, and habits appeared across newspapers and magazines. “Air Hostess Finds Life Adventurous,” read one front-page headline in the New York Times. Indeed, Sadie Ericson was a model of the duality expected of stewardesses: she had social skills and self-determination, glamour and grit. The petite blonde looked “like a captivating French doll” and was “almost magically endowed by looks, temperament, and education to be outstanding” in a profession that required “poise and fearless capacity for action” and “grim courage.”

The next two decades consolidated the view of the job as women’s work. During the Second World War, women took cabin positions across airlines as men served in the military. Passengers began to favor air travel over ocean or rail in the postwar 1950s, due in part to technological advances such as a jet plane that sliced a trip across the Atlantic down to six or ten hours, depending on whether there were tail- or headwinds. Airlines competed for passengers by touting technical innovations, but only so many customizations to the new jet plane existed. Prices were stabilized by the government at four hundred or five hundred dollars to cross the Atlantic, so flying was too expensive to be a regular undertaking for anyone but the rich. Each airline tried to convince customers that it had the highest level of luxury and service, and the women who served a predominantly male clientele became a particular selling point.

On the ground, architecture and design contributed to image. In 10New York City, Bauhaus school founder Walter Gropius designed the largest corporate office building in the world, and Pan American World Airways occupied more than a quarter of its space. On Park Avenue at East Forty-Fifth, it towered above the ornate beaux arts Grand Central Station, displacing it as the area’s focal point. pan am, spelled out in fifteen-foot letters at the building’s crest, visible from north and south, was the last corporate name permitted to top a Manhattan building’s exterior so brazenly. “Marvel or Monster?” a New York Times headline asked readers of the wide, octagonal skyscraper. The building was polarizing but exerted a gravitational pull through midtown Manhattan.

In the sky, perks varied from airline to airline. On the President Special to Paris, Pan Am gave women passengers orchids and perfume and men cigars after a seven-course meal. TWA offered Sky Chief service with breakfast in bed. On Continental, passengers walked to the plane across a velvety gold carpet. Stewardess uniforms conveyed a unified brand with stylish panache. United Airlines hired industrial designer Raymond Loewy, the “father of streamlining,” to design jet interiors and stewardess uniforms; the “Loewy look” in beige-pink wool featured softly rounded shoulders, a trim shawl collar, and hidden vertical pockets. Other airlines enlisted famous designers: Pan Am’s stewardesses sported sky-blue skirt suits by “Beverly Hills couturier” Don Loper, and National Airlines crews wore Jacqueline Kennedy’s favored designer, Oleg Cassini.

By the early 1960s, air travel, once new and uncertain, had become an American institution complete with industrial titans, frequent fliers, government oversight, and clamoring press. Celebrity executives Howard Hughes at TWA and Juan Trippe at Pan Am inspired invention and attracted attention. An upper crust of frequent customers were christened the “jet set” by gossip columnist Igor Cassini; they were a polyglot group dominated by “post-debutantes, scions of bigwigs in business and government or sons of just plain millionaires, 11Greek shipowners’ sons, people with titles (many of these spuriously used).” Repeat fliers, mostly businessmen and members of the jet set, constituted 64 percent of flight traffic. The Civil Aeronautics Board, which regulated prices and routes, supervised the increasing number of local airlines that connected smaller American towns and cities with the larger hubs that flew international routes.

In the 1960s, the appeal of the international was evident throughout high and low culture: James Bond and his jet-set espionage and the television show I Spy; Epcot and the International House of Pancakes; the popularity of the films La Dolce Vita and Endless Summer. At the Monterey International Pop Festival in Northern California, the Beach Boys and the Mamas and the Papas played alongside Hugh Masekela from South Africa, Donovan from Scotland, and headliner Ravi Shankar from India. Pan Am distributed a free bimonthly newspaper to teachers around the country, the Classroom Clipper, with features on individual countries. After the 1950s postwar stability, anything international held a waft of glamour, a counterpoint to the hum and drone of suburbs and nine-to-fives. When French-speaking Jackie Kennedy hosted a small dinner party at the White House, she was advised to “have pretty women, attractive men, guests who are en passant, the flavor of another language. This is the jet age, so have something new and changing.”

A plane was an expensive piece of machinery moving among varied and changing jurisdictions, and it offered its passengers access to nearly all of them: to the countries of U.S. allies, to new republics across Africa and Asia, even to countries that were technically forbidden to Americans amid Cold War tensions. As Fidel Castro’s new regime consolidated power in embargoed Cuba, planes heading to and from nearby Puerto Rico and Florida were hijacked by a dizzying zigzag of Americans and Cubans. Americans sympathetic to the Communist cause sought refuge in Cuba; Cubans hoping to escape an autocratic leader headed north. Hijackings as yet had little impact 12on passengers apart from the inconvenience. Flight crews plied those passengers with food and cocktails to pass the time.

In the United States, the cabin of an international airplane was a sought-after workplace for young, unmarried, mostly white women. Airlines in the early 1960s hired only 3 to 5 percent of applicants. Base pay was commensurate with other acceptably feminine roles: nurse, teacher, librarian, secretary. Perks included insurance, free air travel, paid vacation, and stipends on layovers. Layovers in themselves were extraordinary. A decade earlier, solitary international travel was rarely undertaken by a woman who could not leverage high social status to excuse her lack of a chaperone. And most women had married long before their mid-twenties: in the 1950s, only a third of American women were still single at age twenty-four; some years, more teenage girls walked down the aisle than attended the prom.

The women applying for stewardess positions in the 1960s had in the 1950s been forbidden to wear pants in high school and sometimes even in college. Now, during layovers, a stewardess could pull off the skirt of her uniform, put on slacks, and, chaperone-free, sashay around the museums of the sixteenth arrondissement; she could wear jeans and wander through Mexican markets. Flight routes, experience, and expertise varied by airline. But having a job on any plane was a reason for a woman to roam. What was revolutionary was the lack of should in this job, the plenitude of could.

Lynne had known her chances of getting the job were low, but as she faced the crowd of waiting women, it looked like hundreds were competing for one position. Intimidation became alienation. Now Lynne felt her desire to see the world was not only vague but a little bit vulgar. In a word, selfish.

Then the calculations began: the money spent on the plane ticket from Syracuse, the time spent walking down Park Avenue toward the 13Pan Am Building, the pride she would swallow if she went back to the disapproving friend on whose couch she was sleeping and told her she’d been right.

“This is ridiculous,” her friend had said the night before. “You should be going into social work or research and helping society. Teaching, at least, or having a family, if that’s what you want.”

Standing in the doorway now, facing women who projected such composed beauty and considered style, Lynne thought, Do I really want a job where I have to be someone I’m not? But she had an appointment. She took a seat.

When her name was called, Lynne stood and approached a small room to one side. She had nothing to lose, she thought.

A nice man sat across the table from her. What had she done in her life so far, he asked her, and why did she want to be a stewardess?

She told him about her time in college. “I’ve just spent four years in labs and research and I’m really tired,” she said. “All of a sudden I go to Rome, and I find out that there’s a world out there. I want to be in it.”

He nodded. “Get out of the country, get into this world,” the new Pan Am radio jingle went.

They talked about her foreign-language qualification — German, though Lynne knew that communicating with a German-speaking passenger would stretch her abilities — and the slight tightness of her suit. She had put on a few pounds in Rome, she said with a laugh when he asked if losing a bit of weight would be a problem. All that pasta. Then, since they were already speaking frankly, she told him about her hesitations. If Pan Am was looking for girls’ girls, Lynne would not be the right fit.

At the end of the interview, the man handed her a clutch of forms and instructed her to fill them out. “Where did you get those papers?” one of the beautiful women sitting in the rows of seats asked Lynne, standing up to approach her as she walked through the waiting area. In the moment, Lynne did not register the fact that she hadn’t seen 14anyone else exiting the interview room with papers. She had been instructed to fill them out and hand them to the secretary as she departed, and she assumed that they would then go straight into the trash. She descended from the offices and walked through the austere lobby with its square granite columns and contrasting tones of dark gray and sandy travertine. An eighty-by-forty-foot sculpture with the shape of a globe at its center dominated the west lobby. Hundreds of delicate stainless-steel filaments stretched from the gold sphere up and out in seven directions — one for each continent — and burst into what felt like every corner of the space, glistening, lit from below.

“How’d it go?” her friend asked when she returned from her day of teaching.

Lynne sighed and told her about the women. Coiffed, bubbly, invested in their appearance.

“Be real, Lynne,” her friend said. “You’re going to end up with people who aren’t like you and you’re not going to enjoy it at all.”

Lynne agreed.

The next day, when her friend left for work, Lynne picked up a phone book and traced down the Ps. She called the listed number for Pan Am. She wanted her application pulled. The phone rang and rang.

2

Horizons Unlimited

The grooming classes she was receiving as a pan am recruit would have cost five hundred on the outside, Karen Walker wrote to her mother. Hyperbole, perhaps, but Karen had never known that blue eyeshadow de-emphasized her blue eyes — she should choose a greenish hue — or that a hint of a bright white below the eyebrows would highlight the arch. A grooming supervisor had reshaped her eyebrows, and they now looked 100 percent better, Karen thought. The trainees that spring of 1969 were among the first permitted to keep their hair long if they wore it clipped neatly at the nape of the neck; too bad, because Karen had just cut her blond hair into a bob, the same efficient style she had worn when she worked for the U.S. Army four years earlier.

Karen had arrived at the airline’s Miami training school at the oldest acceptable age: twenty-six. She was a little suspicious of stewardessing. Already an experienced traveler, she was on board for that aspect of the job, but when she saw her fellow trainees standing together on the hot-pink carpeting of the training school, they resembled something along the lines of a Mickey Mouse Club for sorority girls. But the woman who had met Karen’s class of twenty-four in the lobby of the Miami Airways Motel had casually called out each of their names 16from memory, and Karen’s hesitation began to dissolve. In the course of the six-week training, Karen learned about the airline’s history of technical pioneering and its contributions to American military campaigns. She observed the organization exemplified by her stewardess instructors as they delivered thorough, commonsense lessons in everything from deftly carving a rack of lamb to asserting authority during emergency procedures. The other women in her class were young but mostly quick, she thought. After they’d learned how to ditch the plane in a water landing and slide from an airplane’s fuselage into a pool constructed for the purpose, Karen thought that this plane crewed by these stewardesses could handle anything but a bomb or a head-on collision. But just in case, she took out a twelve-thousand-dollar life insurance policy that would be paid to her parents in the event of her death.

The four pages of packing tips in the training manual addressed both the practical and the philosophical. The practical advice included “leave the extras at home … build your wardrobe around one basic color.” Processed wools and linens shed wrinkles quickly. Drip-dry fabrics for lingerie and dresses meant less time standing over a hot iron, time that could be spent at monuments, in markets, or interacting with locals. The philosophical advice was “to enjoy a ‘traveling job’ like yours, do not spend all your energy on non-essentials … concentrate on people, places and ideas; don’t spend your time dressing, changing and repacking.” In capital letters, the last tip read, “WEAR COMFORTABLE SHOES.”

Karen had always preferred hiking boots to heels, and she knew how to pack a suitcase for swift movement. Her earliest memories were of roaming. As a small child she used to wander away from her parents’ house in Whittier, California. She remembered the sensation of it, watery memories of one wide suburban street nearly identical to her own and then another and another. Once, at about age three, Karen had toddled two miles. Her parents had called the police. They locked their screen doors after that. 17

Karen’s family hardly ever left the state. Her father had been an athlete, and her mother had grown up on a farm in Lompoc, the daughter of farmers from Switzerland. Karen played beach volleyball and knew how to skim-board and when she spent enough time in the sun, her hair glimmered and her light brown eyebrows nearly disappeared. With her fluid body language, her arms taut from swimming and spiking, a mouth that usually hinted at a smile, Karen looked like the California girl of advertisements. But with the same devotion that other young women in her politically conservative part of the state directed toward God or marriage, Karen believed in the transformational possibilities of the rest of the world. After college — she had a degree in education from the University of California at Santa Barbara — she liked to sit on the misty cliffs around the area tracing the moon’s rivers across the ocean. “I’m crossing you in style someday,” Karen would repeat, the Johnny Mercer lyrics spooling through her mind as she drew vectors across the Pacific to Alaska, Japan, China, then a hop down to Tahiti, then Australia. She felt certain that a world rich with purpose and excitement waited for her past the borders of California.

Soon she found a way to leave. A girl from school had begun to work at a service club on an army base in West Germany. The enlisted men in peacetime required entertainment in the form of activities and outings. Karen’s education degree qualified her to manage those programs. The pay was good; the experience was better. Karen cried her eyes out to leave her boyfriend, Alan — he was charismatic and athletic with full dark hair and an intense gaze, an avid hiker and backpacker and an intellectual too. But he would be spending the next two years flying navy planes around the world. Karen would not wait at home for him.

“I’m so happy I’m almost speechless,” she wrote to her parents from the city of Ulm. The other two women who would run activities at the service club with her were “hang loose,” and her living quarters encompassed a full suite: she had a bedroom, bathroom, and living room all her own. The club came equipped with board games, 18a pool table, guitars, and an outdoor patio overlooking the Danube. Surrounding the army base was West Germany; encircling West Germany was the rest of Europe. Within six weeks Karen had bought a used VW Beetle on credit and banked enough days off to embark on her first “great adventure”: a trip to Salzburg, where she spent a night in a tent she assembled in the dark. When she woke, she found the fabric had collapsed around her. A circle of giggling Austrian hikers reconstructed the tent as she lay within it, cocooned in her sleeping bag. When she returned to Ulm she pledged to see everything within driving distance. She had been saving up for plastic surgery, but she decided she would not fix what she saw as her too-big nose just then. She wanted to buy skis and tour all of Europe first.

Karen took countryside drives and spent a weekend in Paris. She thought the Mona Lisa was underwhelming, but Parisian streets and people exceeded all her expectations. Here she was, like Sartre and de Beauvoir, observing the city from sidewalk cafés, nursing one coffee after another, overhearing French words with musical consonants she did not understand. She had moved through Southern California on automatic, unseeing. In Europe Karen observed details in an entirely new way. She described it in letters to her parents — the deep feelings, the rambling observations, the minutiae of her conversations. A street performer’s plastic rat; the café table of Bolivian Communists whose dim view of America Karen tried to amend.

To the Bolivians, Karen had explained the “beauty of our system of checks and balances,” but she had her own political doubts. In Germany, she stood amid a peacetime army — two hundred and fifty thousand American troops had been committed to the country after the defeat of the Nazis. Back home, the civil rights movement demonstrated the hypocrisy of the army’s task: 10 percent of the soldiers on West German bases were Black, symbolizing the ideals of democracy and equality, but Jim Crow laws persisted and violence against Black Americans spread through the U.S. despite peaceful protests. “I don’t see how President Johnson can send troops to Vietnam — I don’t see how he can send 19troops to the Congo — I don’t see how he can send troops to Africa and can’t send troops to Selma, Alabama,” John Lewis had said, speaking to an assembled crowd in the southern city, his skull fractured by a police nightstick. No federal troops had been sent to protect the lawful marchers. Dozens were beaten by state troopers’ clubs.

A Department of Defense report would later reveal the extent and pervasiveness of hostility toward Black GIs on American bases in Germany: cross burnings, Ku Klux Klan meetings among servicemen, and threatened boycotts of German business owners who chose to serve Black GIs were all documented. All Karen knew was what she observed: The way the men segregated themselves rigidly by race at social events. The young Black man who was stabbed in the torso and staggered into the service club but refused to report the incident no matter how hard she pleaded. The “ugly little lieutenant” who disliked how chummy the three women had become with the troops, including Black GIs. The five soldiers who beat up one Black GI. The bite marks on arms and necks after a game of football. “This damn Army is getting to me,” Karen confessed to her parents in a burst of frustration. “I’ve never seen so many outright injustices in my life.” She was fed up and she felt useless. She began to save money to quit and travel.

When she was young, Karen had flipped through her parents’ copies of National Geographic, mesmerized by the color photographs. Now she was tantalizingly close to the places that had captivated her as a child. “Life is too short to waste even one precious year on dullness,” she wrote to her parents. “Don’t misinterpret this as Jet Set philosophy — please.” She signed her letters with a tiny stick figure in a dress and a bobbed haircut, a suitcase hanging from one arm.

Karen spent a year and a half traveling. When her money ran low, she hitchhiked, then worked through the winter at a service club in the Alps. She picked melons on a kibbutz in Israel and camped out in a van in Portugal. When her stamina and money ran out, she went 20home, where she resolved to live a stable life. She got a teaching job at a high school and rented a shared bungalow by the beach. Her students loved her. “Hey, Miss Walker!” they shouted when they saw her biking around town on Sundays, their bodies halfway out car windows as they waved. But again, Karen’s restlessness percolated.

When she told her parents she had been accepted by Pan Am and was going to Miami for training, they called her a quitter; she had quit the army, quit teaching, Karen the quitter. But everything she learned in her six weeks of training in Miami vindicated, at least to Karen, her choice.

“In our advertising, we use the slogan, ‘World’s Most Experienced Airline,’” read Horizons Unlimited: An Indoctrination Course for Flight Service Personnel, the most conversational and ruminative of the three texts used in training. “The key word of this slogan is ‘Experienced.’ The root of the word ‘experienced’ is from the Latin peritus, meaning a trial. To this has been added ex, so that the combined word means, ‘out of trials …’ Or, ‘knowledge gained through one’s own acts.’”

Karen had learned from her travels and the constraint she felt back at home. Wanderlust was not just a condition of her youth. But first, Karen discovered, she and the twenty-four other aspiring stewardesses who entered training that Monday — there was a new group every week, and in less than a year, Lynne would walk the same pink carpeting and sit in the same classrooms — had to earn admission to the world that they craved. An airplane, all of the stewardesses learned, could rotate in three directions around its axes. Those directions were the plane’s roll, pitch, and yaw. Their training courses similarly pointed all aspiring Pan Am stewardesses in three directions: technology, service, and image. None functioned independently of the others.

Paragraphs of text explained the difference between thrust and drag — the forces that propelled an airplane forward and pulled it back — and the difference between a plane’s allowable useful load and allowable cabin load. Diagrams demonstrated how to calculate each based 21on the principles of weight and balance and also located and named the various parts of the plane: brake spoilers, vortex generators, horizontal and vertical stabilizers, wing flaps, engine pods, ailerons. Such practical information contributed to good service; passengers were often curious and the stewardesses were expected to competently answer questions using “simple and direct” terminology. Stewardesses should “attempt to identify” the first-time rider, the manual advised, “and make every effort to make his flight most interesting and memorable.” Keep conversation tactful, slang-free, oiled with eye contact, lightly logistical. Points of interest, location, meal service, ETA — such topics could alleviate the reasonable anxiety and fear of being trapped in a metal tube high above the earth.

Emergencies occurred very infrequently, but the women were trained to reassure a nervous passenger, and crews and airplanes were well equipped to handle any incident. Safety instruction during training included preparation for evacuation of the aircraft by land and water. Maps of each jet in the service manual — variations on the 707, 720, and others — showed the locations of ropes, rafts, first-aid kits, escape slides, and spare life vests. A stewardess’s role in an emergency was mapped out according to her position on takeoff; evacuation by land dictated different responsibilities than ditching the plane in water did. Aspiring stewardesses practiced inflating and then tossing the enormous yellow raft into a ditching pool built specifically for the task. In an emergency landing, the chief stewardess would notify passengers with detailed but calm announcements over the PA system. “Establish firm passenger control and simultaneously issue instructions,” the guide directed. The rest of the stewardesses were to follow her commands, identify competent passengers to help them throughout the cabin, and return to their crew seats at five hundred feet. Manuals would soon include sections on hijackings too. “As in any emergency situation, coordination and communication between members of the crew are essential,” the manual read. Stewardesses should communicate with the hijacker, keeping him occupied with conversation 22and transmitting as much information as possible to the captain. The women were told to “become a neutral friend,” to serve caffeine-free nonalcoholic beverages, and to try to lead the hijacker into asking to land the airplane. But they were also to keep such tactics confidential. Specific passenger questions about Pan Am’s security measures should be “left tactfully unanswered.”

The manual instructed stewardesses to use titles for the crew in the presence of passengers: “Captain” for the pilot, “Sir” for copilot and engineer, “Miss” for other stewardesses. “Intra-crew courtesy” contributed to setting a flight’s tone, and only English was to be spoken among the crew. The stewardesses were given rules to follow outside of the plane too. The only permissible situation in which a stewardess in uniform could smoke on the ground was when she was seated after eating a meal. On a plane she could light up in the galley after meal service. General etiquette guidelines followed Emily Post rules; no discussion of politics or religion, ever. “Tact and diplomacy,” the manual read, “are required when discussing topics relative to the customs and ideals of the passenger’s country.” The manual showed line drawings of the pins of various fraternal organizations — Elks, Masons, Knights of Columbus, Kiwanis, Optimist International — and encouraged the stewardesses to introduce two passengers wearing the same pin if both were agreeable. Military charters were “an excellent and lucrative source” of revenue for Pan Am; courteous service on military flights was of paramount importance. At the end of the course, the women were tested on how to properly address a U.S. senator, Catholic bishop, prime minister, ambassador, and rabbi.

The word diplomacy appeared over and over in the manual’s sections about service; stewardesses would be called upon to interpret for foreign passengers, respond appropriately to different religions and nationalities, and control rowdy children. Even where that word did not appear, the concept threaded through. Stewardesses were taught to prepare Malayan chicken curry, to offer chopsticks as well as silverware roll-ups on any flight across Asia, to prepare Passover meals and 23know that the message of Passover stressed “the theme of human freedom and the sacrilege of human bondage.” The airline’s reputation as a “truly international airline” relied on internationally knowledgeable service. It also relied on stewardesses knowing how to prepare fluffy scrambled eggs in a pressurized cabin and how to mix an excellent cocktail. Stewardesses circled answers on quizzes to prove that they knew what to put into a highball first (liquor, ice, or mixer) and how to make a dry martini in flight.

Pan Am stewardesses learned that projecting the right image was essential to good service. Every flight began with an announcement that was read in English and the language of the destination, which was part of the reason why every Pan Am stewardess was tested on her language proficiency in her interviews. “It has been pointed out that in many cases all passengers speak English and there would seem to be no reason for non-English announcements. However, we have a second reason for making these announcements,” read Horizons Unlimited. “That reason is showmanship. The announcements, needed or not, add a continental flavor which Americans love. Our passengers are starting out on an adventure and we are helping them to get the feel of it immediately. As the first cosmopolitan people they meet, our personnel assume greater stature in their eyes.”

Along with their linguistic dexterity, Pan Am’s stewardesses conjured the proper image with their physical attributes. Illustrations in the manual showed a variety of mouth shapes and how to apply lipstick to each to achieve a “more beautiful smile.” There was posture instruction, skin-care techniques, makeup application, haircuts — grooming lessons took nearly as much time as first-aid training. Girdles, white gloves, and slips underpinned and accessorized every uniform, regardless of the weather in the plane’s final destination. A “natural look” was outlined in the rules for makeup. Red, rose red, and coral were permitted on lips and nails. “Lavender, purple, orange, insipid pink, iridescent or flesh color” was not. Hair was to be cut above the shoulders or pulled back at the nape of the neck. No seductive or “extreme” 24styles were allowed. A 1959 memo circulated among stewardesses gave the rationale for banning more dramatic makeup choices. Psychiatrists explained that “outlandish” makeup reflected “unsatisfied personality need” or “emotional disturbance.”

Pan Am’s goal for its stewardesses was femininity and sophistication that stopped short of sexual availability; they were to be clean, pretty, ladylike, and uniform, their every angle enforcing corporate identity. “Grooming monitors” ensured that stewardesses maintained the look that each one had when training ended. Management’s approval was required for a change in a woman’s haircut or color; supervisors kept notes in stewardesses’ employee files on the hairstyles they were allowed to wear. Some of the women, like outdoorsy Karen, welcomed instruction in how to achieve this professional look, even if they eventually strained at such oversight.

A woman didn’t have to look like a model to become a stewardess, nor did she have to put overt effort into maintaining her appearance. The natural look that Pan Am favored could be attained with relative ease. But the job did require a woman to be born lucky, with symmetrical features, clear skin, height between five three and five nine, trim-ish body type. It required, too, a woman willing to adhere to the beauty norms set by a company run by men. Karen signed on, for now.

After training, Karen was assigned to Pan Am’s New York base, flying out of JFK International Airport. In her first months she traveled the airline’s routine flights — shuttles around the Caribbean and South America, out to London and back. She immediately recognized in the movement of a crew in the galley the easy camaraderie and physicality of her cheerleading squads — a hand on the small of the back, a “Behind you” as someone slid by.

She roomed with four other stewardesses in an apartment on Eighty-Ninth Street and Central Park West. The apartment was filthy; she cleaned and cleaned, and still strips of paint drooped from the 25walls. But Karen rarely spent more than a day or two at home every few weeks, and even when she was in New York, she was out seeing the city with the help of her copy of New York on $5 a Day — her bible, as she called it. On Sundays in the summer, when it seemed as if the city’s overlay of taxis and pedestrians and hot-dog and pretzel carts had been peeled from the sidewalks and streets, Karen walked down the middle of the empty avenues. She read One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and The Confessions of Nat Turner atop the boulders in Central Park. She walked into Elaine’s once, the Upper East Side haunt of Norman Mailer, Mikhail Baryshnikov, and other famed authors and artists, though she had no money to pay for a meal.

Sticking to a budget at home meant she was able to make purchases in foreign countries. Karen met stewardesses who plotted their layovers around shopping — Italy for leather shoes, Paris for hose, Beirut for jewelry, a pearl necklace in Hong Kong. But there were also women who bid their flights — requested routes — around Elvis Presley’s tour schedule, or graduate-school coursework, or adventurous exploration, landing near Mexico’s pyramids or as close to Timbuktu as possible for their two weeks off. The cities of specific foreign countries were coordinates on each stewardess’s personal map. Clothing, shoes, and jewelry became accessible, but they also became talismans of knowledge, security, and choice. What a stewardess wore when out of uniform served as a reminder that she was now living a life guided by desire and possibility.

On Karen’s first flights, the faultless sophistication of the European stewardesses intimidated her. She had to remind herself that she too had access to what she saw as the source of their sophistication — she too could move with ease around the world and become familiar with places that normal Americans like her family might see once or not at all. Every time she stepped onto the corner of Central Park West to hail a yellow taxi for the Carey bus, standing on the street in her crisp blue uniform and her nylons and sensible heels, she nearly jumped out of her skin with excitement. She would go to John F. Kennedy 26Airport and get on a plane, and when she stepped out of it, she would be in a foreign country. The independence of her new life was just right; she was living in New York City but she was gone more often than she was there. In the same way that she read approvingly about the anti-war marches in the city but did not attend and admired the feminist movement but was not active in it, Karen enjoyed half participation in the clubby airline life. She rarely went to crew parties on layovers. She preferred dinner on her own.

On one of Karen’s first flights to Puerto Rico, the captain called her into the cockpit to look at Cuba below. The island appeared enormous. Karen observed green fields of crops. She saw what she thought was a missile site with trucks coming and going, then lush mountains of variegated colors and very few people as the plane continued on. It was no wonder that the hijackers always went to Cuba — airplane skyjackings had risen into the dozens every year, and nearly all of the hijackers had directed the planes to Havana; “a true democracy,” said one skyjacker. Karen left the cockpit to finish the drink service.

When the plane had passed over Haiti and the Dominican Republic and was approaching San Juan, the captain again called Karen up to the front. “Strap in,” he said, gesturing at the seat behind him.

She sat down as he narrated how he would land the plane. The copilot and flight engineer chimed in, describing the function of different instruments, how the steering mechanism and gauges worked. As the plane descended ever lower, the ground rising toward the cockpit windows, the captain took his hand off the steering yoke and pointed at different sights — the good hotels, restaurants, and bars he had come to frequent while in Puerto Rico. The copilot and flight engineer followed the captain’s finger. The cockpit was now close enough to each of the buildings that Karen could make out window dressings and pedestrians walking into doorways. She felt the blood slide out of her cheeks. The men’s focus snapped back to the task at hand and an instant later the plane was on the ground and the men were laughing at Karen, the new girl startled by a simple landing.

3

A Woman in Uniform

The skirt of the pan am uniform hung an inch below Karen’s (and every other stewardess’s) knees. The long white blouse fit snugly around her waist and tucked into the skirt so that even when she reached into the compartments above, it would not pull out of the waistband. The jacket, introduced in 1965, was boxier than the Don Loper–designed 1959 uniform; Pan Am called it the “easy” look.