Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

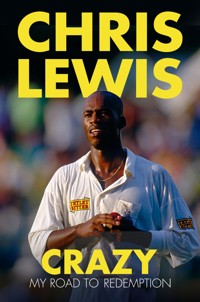

'In that split second, perhaps the first sobering thoughts I have had in months become so obvious and apparent, and when that officer returns after having checked the cans and found cocaine I know that, from that moment, everything is going to change.' 'Crazy' Chris Lewis played in thirty-two Test Matches and fifty-three One-Day Internationals for England. At one point he was regarded as one of the best all-round cricketers the country has ever produced. However, feeling at odds with the middle-class nature of the sport, he regularly courted controversy off the field – and the tabloids happily lapped it up. His naming of England players involved in a match-fixing scandal led to his early retirement at the age of just 30. After this, he withdrew from the limelight until, in 2008, he was arrested for importing cocaine from the Caribbean and sentenced to thirteen years in prison. From his arrival in England from Guyana with his parents, through his colourful cricketing career, his arrest and subsequent trial, his time in prison and how he finally put his life back together, here Lewis recounts his remarkable, redemptive story.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 326

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published in 2017

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2017

All rights reserved

© Chris Lewis, 2017

The right of Chris Lewis to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7509 8325 9

Original typesetting by The History Press

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

1 The Arrest

2 Remand

3 The Young and Innocent Chris Lewis

4 My Developing Career as a Boy in England

5 The Rise and Rise

6 The 1992 World Cup and a New Career

7 On the Up and Then Down Again

8 The Downward Spiral

9 Spot-Fixing and the Stitch-Up

10 The Wilderness Years

11 Guilty

12 The Beginning of the End

13 Release

14 The World of Now – 2016/2017

15 So, Who is the Real Chris Lewis?

16 Who is the Real Chris Lewis?Part 2 – The View of the Ghostwriter

1

THE ARREST

I’ve never been so apprehensive in my life. It’s Monday, 8 December 2008. My Virgin Airways plane lands from St Lucia into the South Terminal of Gatwick Airport. It’s just after eight o’clock in the morning.

I’ve arrived, and I’m scared. While my fellow travellers nervously grip their partners’ hands in anticipation of the first violent contact with the tarmac, all I can think of are the cans of fruit juice in my luggage that contain cocaine. Paranoia seeps from the air vents and heightens all my emotions. I’m unsure of what’s real or what’s unreal. Everyone appears to be looking at me with accusing eyes.

There’s a family occupying a row further along the fuselage, and when the father looking around the cabin turns in my direction, I’m sure that this brief eye contact is a tacit accusation. He seems to look at me with an accusing eye, but how can he know? Maybe he’s a police officer and is keeping an eye on me, because they already know. This paranoia is going to be the theme of the whole morning.

The airport at this time of day is quiet. I walk to passport control and there are two men standing behind the counter. I assume they’re checking all the travellers, but they seem to be looking directly at me and no one else. I walk through passport control to the baggage reclaim area, where bags are slowly beginning to emerge from the carousel flaps. Many cases travel the full circle a number of times, while others are claimed immediately by their owners, who then head to customs. For a while, there’s no sign of my bag. It seems like an eternity, but then my luggage emerges from the plastic strips. I look at my bag nervously. It’s slightly ajar, the zipper half open. I hadn’t put any padlocks on them. But then again, I’m very tired and realise that in my many years of travelling I’ve often failed to close my bag properly. ‘Come on, Chris, pull yourself together. You’re just overthinking everything,’ I tell myself. I look around and pick up my bag, taking a deep breath. I follow a group of fellow passengers towards the ‘nothing to declare’ exit. They walk through but before I can reach the exit one of the officers I thought had been looking at me earlier is now standing at the exit. His voice is level and calm as he says, ‘Excuse me, sir, may I check your luggage?’ My bag is taken to one side and the officer looks through it. He reaches for the three cans of fruit juice and removes them. Inside, I’m shaking, trembling. I can hardly stand.

The officer takes the cans to be X-rayed. His body language betrays nothing as he lifts the cans and places them on the X-ray machine. In an instant, I have a thousand thoughts that trigger the infinite consequences of my actions. I try to breathe more slowly. The officer returns and he tells me that the X-rays have revealed nothing. A sense of relief washes over me, but it’s momentary as he explains that he is going to have to open the cans. Around me normal life carries on as people chat on their way back from various destinations, but I feel disconnected from it, as if in a bubble of my own anxiety. The first sobering thoughts I’ve had in months become so obvious and apparent, and when the officer returns after having discovered the cocaine I know that everything is going to change. In an instant, the future looks very different to the one I had imagined. The officer takes the cans away and for a brief time I am alone. For a second or two, I almost convince myself that everything is going to be okay, but it passes before I can blink, as reality floods in and drowns out any sense of hope. ‘What’s my mum going to say?’ What are my brothers going to think?’ ‘What about the press and everyone else?’ No part of this is going to be good. The customs officer returns after what could have been minutes or seconds – I don’t know. He tells me the cans have tested positive for cocaine. Doom and gloom descends. He asks me to follow him, and I do. I am taken upstairs and to the left into what looks like a normal waiting room. At this time, I can’t say I’m even thinking any longer. I can feel the panic running through my body. Externally, as ever, I try to remain calm, but inside I’m racing. I’m like the duck that seems at ease on the water while underneath its legs are going crazy. I’m waiting for the police to arrive, and when they do, I am arrested. So begins a long journey, one that would take six-and-a-half years of my life.

I arrive at Brighton police station. I don’t remember much of the journey. At the station, I’m processed and put into a cell. My mind continues to race. In the cell, I’m alone for the first time. My head is spinning, I could scream with disbelief about where I am. A while later, I’m told that I can make my phone call. There is no doubt who I am going to call – my younger brother, Mark, but then I remember he’ll be at work and unable to take the call, so I choose a close friend instead. I ask them to tell my brother where I am and what has happened – that I’ve been arrested.

My night in Brighton police station is just surreal. It’s hard to comprehend quite how I’ve moved from one state of being to another so rapidly. A few hours before, I had been a free man returning home, now I’m a criminal facing a long sentence in jail and having to tell my loved ones not just where I am but what I have done. I spend one night in Brighton before I’m taken to a prison in Surrey. Driving into the prison, I begin to recall all the prison movies I had seen as a younger man. We all have a vision of what prison must be like, and I’m about to experience mine at first hand; this is so far out of my comfort zone, I can’t believe it.

I doubt whether I can survive even a couple of days in here. I don’t think so. With the cell door locked behind me, it’s the first time in a long while things are quiet. I think about my family but it only makes my head spin and I want to scream.

When I decided to import drugs I never gave my family a thought. I didn’t think about the negative aspects of what I was about to do. I was never going to be caught and so I never had to think about the consequences for my family. Now in this cell they come to mind. What have I done? I sit and think about the countless others who are going to be affected by the fallout from this. My family and friends are going to be affected and that’s hard to cope with because, although I will have to live with my mistakes, they will inadvertently have to live some of this with me too.

The moment I start to think about those close to me, what I have done really begins to hit home. Nobody can knock on my door now, but others will be doing that to the people I care about. I have just added to their burden. As the elder son and brother, it was always my job to protect my family and I have just failed in that spectacularly.

2

REMAND

I emerge bleary-eyed into my first morning of incarceration at HMP High Down in Surrey. As I sit in my cell, all my thoughts are negative and I seriously doubt whether I can cope with this new reality. Simple things that I normally take for granted, like the liberty of walking down the street, are at the forefront of my mind. I yearn for the simple things, not yearned for in decades. The truth is that I already know it will be some time before I experience normality again. The best-case scenario is that I’ll get bail while the prosecution prepares its case.

My solicitor arrives and tells me that the application for bail will take a couple of weeks. Even a fortnight now seems like a lifetime. I guess I’ll just have to cope as best I can. Two weeks – surely I have the mental strength to get through that short period. Over those couple of weeks I must have cut a sorry figure. That’s the emotional stress. I’m in new territory; I have no skill set to deal with this. I say very little, there is nothing to say, but I’m trying hard to remain positive.

Within days I get a job serving food to other inmates, which gives me something to do three times a day. This job allows me to get out of my cell, which is important, as without the work I can be locked up for twenty-three hours a day. The activity helps the day pass more quickly and has the added benefit of me getting more food, so I don’t feel as hungry. I’ve never been the fattest of people, and keeping my weight up has often been something I’ve had to watch. In here, within a couple of days, the weight just falls off.

As well as my work in the kitchen I try to occupy myself further by wearing a second hat. I’m also a ‘foreign rep’, which basically means I go to see new foreign nationals coming into the jail. I ask them about their needs and help them to navigate their way through the criminal system, which I too am learning. Even in the state my mind is in, it’s quite easy to see and appreciate that there are people here who are in a worse predicament than myself – people who don’t speak English and therefore find it hard to understand how the system works. I try to make it easier for them. I also spend some of my time as an anti-bullying rep, anything to keep the grey matter working. Bullying within the prison service is a big no-no. I’m paid £1 per day for the servery work; the other tasks are unpaid but they keep me busy.

Although I’m on remand, only just having been arrested, I’m treated like all the other prisoners. The days pass in a routine way, as you would expect in such an institution. My cell is unlocked early and I begin serving at 8 a.m. for about forty minutes, after which time I tidy, wash up and generally help out. Afterwards I have my own breakfast, which is usually cereal or toast, except at weekends when we might have a cooked breakfast. Most days my job serving breakfast is over by 10 a.m., unless there’s a deep clean of the kitchen, which gives me a short time to fill before the lunch serving. I’m then back in my cell until the evening meal at 6 p.m. I spend that time reading and trying not to think, as any activity is better than dwelling on my predicament.

When I can, I walk around the wing or go to the gym. It’s a blessing that my serving job provides me with something on which to focus and the opportunity to be out of my cell for longer periods.

At night, there is no hiding in routine and activity, and so the nightmares come. It is quite simple: I am afraid. Fear is a part of life, but this is just too big a fear to deal with. In fact, it’s more than one fear, it’s a host of them. One nightmare involves me trying to run to get away, but get away from what – I can never tell in the dream. I’m trying to get my groove on and run very fast, but instead I’m running in slow motion like Steve Austin in The Six Million Dollar Man. Another is being up high in a precarious position, like on the edge of a crane, with the wind howling around me. I never fall but I’m always scared that I will. As the time passes, I learn that I’m never going to fall, but this does not remove the fear; all I can see stretching into the distance is day after day of the same nightmares. Yet, through all of this, on the exterior I still try to remain as calm and polite as possible, even though my nightmares inform me that I am absolutely bricking it. There is a fraction of time just before I open my eyes when I can allow myself to believe that I’m in my own bed, in my own house, and that prison was all some terrible dream. But then I open my eyes and the cell is still there. I realise with dread that this nightmare is real.

I may be consciously occupied doing something with my mind, but there is still a horrible feeling of unease that is always there, right by my side. I can’t get shot of it, whatever I try. I am not always consciously thinking about what the unease is, but it’s always there. In a matter of days, I’m already noticing that I’ve become a lot greyer. I had one or two grey hairs before, but now they’re increasing rapidly.

This all goes on for the two weeks while I wait for news of my immediate future. Finally, I receive the date of my bail hearing. When it comes, I must face the immediate disappointment that I’m not going to leave prison for my day in court, as the hearing will be via videophone.

I am taken to a room where my future will be decided. Many others have been in this room today, some were successful and some not. But I’m hopeful I’ll get bail, and with it a little space in my head, temporarily at least. I watch for half an hour while the two sides of the argument are given. The State is arguing that I’m a flight risk, but I suppose that depends on how you would describe a flight risk, as I reckon I could only make it to outside this room before someone recognises me at this moment. But I’m not the master of things to come, I gave that up when I broke the law. The faces retire to decide my fate. While I wait, I stare at the empty chairs. I am devastated – they say I’m a flight risk. The hope that had sustained me through the first two weeks evaporates in an instant and I want to scream, but I have to bottle it up, as it would serve no purpose. I must try to focus and get my head around this.

Expressing my disappointment would serve no purpose. There are plenty of people in this prison who have been sentenced and are facing many years, even life, yet they find a way to cope. I have never considered myself weak so there must be a way for me to cope. These inmates are an example but not an inspiration; my aim is to reapply for bail in a month and to get it right next time. So, it’s back to setting that goal and working towards it – just another month.

Time passes relatively quickly. It is something of a conundrum: the days seem to pass so slowly, but a month flashes by in comparison. I decide that this is because jail is full of routine and drudgery so that, looking back, it is very hard to separate one day from another, as each day is filled with uneventful regularity. For forty years, whatever problems I had, I could at least walk out the door and go where I wished, but that privilege is no longer mine. It’s a strange feeling, knowing I can no longer make those choices. All this puts the previous problems in my life in perspective and I realise that what I thought were major issues were actually insignificant ones.

I know I must find a way to cope in prison and believe that things will get better. All the choices were mine and only I am responsible for my incarceration. I could be in prison for fifteen years – it almost takes my breath away thinking about that – so the sooner I get used to that, the better. I’m not dwelling on how I got here and why I made the choices that led to my arrest. You may ask, ‘Why not?’ Well, if you fall into a river and get swept along by the current, you don’t think, ‘I wonder what caused me to slip?’ You think, ‘How the fuck am I going to get out of here?’ Once the immediate fear has gone then you might go back to find out why and how you fell in, but not right now. That said, these questions would start to form later. Right here and now, I have more pressing things in my head – mainly my current predicament. I need to deal with that before I’m even capable of thinking about how I fell off the bridge into the river.

My fear has created a view of my experience that is at odds with reality. We tend to get our view of prison from TV and movies and there are things that go on in jail that are mirrored in fiction.

However, it’s not as bad or as frequent as the movies would have you believe. Prison is not supposed to be a pleasant experience, it is a punishment after all, and it’s definitely not like Butlin’s, as some would have you believe. Okay, I have a TV in my room, but that doesn’t compensate for not having your freedom or spending time with your loved ones. I understand that I made the choices that put me in here, but that doesn’t make my situation any more comfortable or pleasant.

I receive my first visit. It’s my brother, Mark, and I have no idea what I can say to him. Saying ‘I’m sorry’ at this point seems weak and pointless. I guess it’s one of those situations where I’ll have to sit here and accept whatever comes. It’s a very difficult visit. Sitting in front of Mark, my fear doesn’t seem to be as important and, for a moment, it’s gone.

As a young boy, my desire to set a good example for Mark has helped me greatly in my career – the fact that he was present and watching what I did drove me to work harder. That makes me feel even worse now. I cringe when I think of the size of my failure. Mark reports back to my mum that I’m okay, but that I was constantly rubbing my head, and they all know that’s what I do when I am stressed. It occurs to me that all visits could be as emotionally charged as this one, and a visit from my mum even more so. Thinking of her is very difficult and I know that I don’t have the words to explain how I feel or to begin to explain why I made the choices I did.

When I see my family, I’m filled with an overwhelming feeling of disappointment in myself for what I’ve done to them. But still, they come, and I am so pleased to see them. Despite my guilt, nobody points an accusatory finger and no one asks why. They just seem to instinctively know how I am feeling and support me.

My friends also begin to visit and, finally, after weeks of incarceration, I laugh. Because they are mates they ask me things that a family member doesn’t and it’s something of a relief to be able to do that. I can tell them how it is in here and that, in spite of everything, I’m okay.

My mates and I have been through a lot – grown up together, got in trouble together – and so to them this is just another scrape, albeit a more serious one. But we can talk. They ask if I did it, and there’s no judgement – that’s a comfort. We talk about how we dealt with situations we had been in in the past, trying to find some positivity from difficulties we overcame, and we remind ourselves that we have coped with things before. We all understand that this is much bigger, but the principle is the same. So, focus remains my mantra; find any peace of positivity and focus on that.

Back in my new world, my final application for bail is denied. I didn’t prepare myself for this but I seem to be coping better. I’m not as devastated. I simply set my internal clock for the next four months ahead to my trial. I find out my case is going to be heard on Monday, 17 May.

I go from being ‘the accused’ to being a convicted criminal. The judge sentences me to thirteen years in prison. Thirteen years! I look over at my brother, Liam, tears in his eyes. He comes close to the cage and I tell him to take care of our mother. I’m now worried about what I may have done to her health. Very quickly I’m back downstairs in the cells. It’s been hard trying to describe the emotions of being sentenced to thirteen years in jail – the fear of what’s to come, the disappointment in myself, the pain I’ve caused my loved ones, and not having the opportunity to make things better for many years. These thoughts seem to come all at once. Shit, it’s all too much. It’s like, it’s happening, but it can’t be happening. Such a weird state, disbelief I guess.

3

THE YOUNG ANDINNOCENT CHRIS LEWIS

It was Friday, 10 March 1978, just after 10 a.m., and I had just landed in London from Guyana. It was my first time on a plane and so for all my time spent in the sky I stayed in my seat. I didn’t understand how anything around me worked. I was venturing into a new world, one that would change my life forever. I was neither perturbed nor frightened, as this was an adventure for the 10-year-old Chris. I had left my home in Guyana to come and live with my mother and father in England, the start of a new life away from my friends. It was the kind of journey travelled by many black people at that time.

My mum and my Aunt Hazel came to collect me. My feet were hurting and my very smart suit was a little tight, since it had been made for me a few months earlier and I had now grown. My aunt picked me up and carried me through the airport, beyond the thousands of people that were arriving and leaving. I had never seen anything like it. Everything was so big and so different. When I had imagined the streets of London, they were all paved with gold, but I had also imagined everything else to have similar hue, yet I was greeted with this blanket grey, which seemed to head from the ground to the sky with nothing else in between.

The following day, Saturday, I woke at my aunt’s house in Harlesden, where my mum had been living. There was a chill in the air that I had never experienced before, but at least there was one thing I could do that would bring me back to normality – I could find a radio and listen to some cricket. Once I had tracked down a radio, I started trying to tune into the station I had listened to back in Guyana. I spent hours trying to fine-tune the radio to find the cricket. Initially, I just couldn’t comprehend why it wasn’t there.

I did this for the first week I spent in England. No cricket – this was going to be hard. I realised that I wasn’t enjoying my new home. I spent a lot of time missing my gran and missing Guyana, desperate for some familiarity.

Ah, my gran. Back in Guyana, everyone was brought up with traditional British values, with discipline at the forefront; after all, the country had been a British colony for 150 years until 1966. My job as a small boy was simple: I had to go to school, behave myself and be well mannered – be seen and not heard. I certainly never answered back to my elders, not that I was always the best behaved. As a young boy, I spent a lot of time outdoors with my friends playing cricket, climbing trees and teasing the local dogs so that they would chase us. Some of this behaviour got us into trouble. We were pretty fearless at that stage, only having the fear of our mums. One of the things my mother taught me was not to follow others; but, like all kids, I would do just that. My mum quickly snubbed it and she wouldn’t accept any excuses. She would ask me, ‘If your friends jumped off a bridge, would you?’ The answer would, of course, be no and that would be that.

Our home was filled with music and my first ever memory is of my mum dancing. I wanted her to pick me up but she was enjoying herself, so I began to cry – crying seemed to be a response to just about everything when I was 2 years old – but moments later my Aunt Hazel had lifted me up and I was flying through the air and all was good in my world once again.

Our family was an extended one, the head of which was my grandmother, Eunice. We grew up in Agricola on the outskirts of Georgetown, Guyana, in South America. I was born there on 14 February 1968. Our community was a mixed community, one made up predominantly of West Indians and East Indians and a sprinkling of Chinese and Portuguese.

My father, Philip, had left to join his mother in England soon after I was born. Back then people saved up to immigrate to America, Canada or Britain, usually one member of the family at a time, looking for a better life. In the Caribbean, in those days, the whole idea of England and Englishness was idolised, it was the pinnacle of everything. England was seen as a land of opportunity and I knew from an early age that I would be going there.

My gran had ten children: four boys (my uncles James, Wilfred, Colin and Michael) and six girls (my mum, Patricia, and my aunts Princess, Hazel, Marine, Juliette and Cleopatra). Princess died before I was born so I grew up with nine of my gran’s offspring all in the same house, along with my grandma, her partner, my sister Vanessa, plus my cousins Susan and Felix. Large, extended families were pretty much the norm for our community.

Uncle James was a carpenter. He did carpentry around the house and made figures and decorative maps out of wood to literally carve out a living. Then there was my Uncle Wilfred. He had been in the army before becoming a tailor. A good-looking man with a big Afro, he wore high heels and an open shirt showing off a medallion. He was so cool, the coolest guy around at the time, and I wanted to be just like him.

Much of Guyana is below sea level and gran’s wooden house, like most houses here, was built on stilts. At the front there were stairs that took you up to a veranda where you could sit outside. There were four bedrooms and at night there would be three or four in the bed and some on the floor, but this was normal. If you had a large family, whether your house had two bedrooms or just one, that was how people lived, which may remind some people of the conditions of the Bucket family in Roald Dahl’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory.

At the back was the kitchen. There was electricity, but we cooked on gas from cylinders. In Guyana, you had to know how to do things. We kept chickens, and from time to time my gran would ask my uncle to catch a chicken and do the necessary – chop its head off and pluck the feathers. When they were feeling particularly mischievous, they would break a chicken’s neck and watch it run around for a while. Then we would build a fire and cook the bird outside.

As a young boy, I would watch what they were doing and by the time I was 5, I could build my own fire and cook outdoors. I used two concrete bricks, one at each end, to support a metal sheet that I would cook on. Then I would put the wood underneath, light the fire and put the pot on top. These were the things I had to learn when I was a young boy growing up. All of us had to be, to some extent, self-sufficient. That was the way of the world for us.

There was no running water indoors, so in the morning we had to go and fetch our own water from a pump at the end of the road to have a shower. From the time I could stand, I went and got my own water. This was very normal for our community; we were all being prepared for later life. In this environment, there was no social security or handouts. If you couldn’t do it yourself, it wouldn’t get done. If everyone was proactive and you weren’t, you stood out like a sore thumb.

So, as a young boy, I learned to cook, clean and sew, and I was even handy with a cutlass, which we used to cut the grass in the back garden. Having said that, one day, being a bit carefree with the cutlass, I nearly chopped off one of my toes. It was hanging on by the skin but somehow it managed to reattach itself as if by magic. Losing a toe would have had a disastrous effect on my future career as a fast bowler. Another time I jumped out of a tree without noticing a stake sticking up out of the ground and it went right through my foot.

While I don’t remember being ill, my childhood contained plenty of such mishaps or, as I would call them, learning experiences. I was once run over on the road outside my house, but I don’t recall a thing. I was 5 or 6 years old at the time and I do remember waking up in hospital and looking around and thinking, ‘What’s going on?’ I was just about to panic when I looked out of the window and saw my gran coming into the hospital. My last recollection had been of playing happily the day before. A day and a half was completely lost and I have never been able to recall the accident. Apparently, I was standing on the wooden bridge over the little river that led to our garden when a car reversed and hit me.

I must admit that I do find that very strange. When we were kids, we were running around outside all the time. We weren’t slow and I would have thought it unlikely that a reversing car could have caught me unawares. We were constantly aware of traffic, as we were already playing cricket a lot in the road and had to move our stuff out of the way to let the cars go by, although, fortunately, there were few cars in our road. I thought to myself, ‘Were you sleeping? How did you not see or hear a car coming onto the bridge?’ But that’s the story. To this day, the after-effects of the accident bring on occasional headache and eye ache.

I was 7 or 8 when I first went to visit one of my aunts, who had moved into a relatively new complex. She had the first flushing toilet I had ever seen. We had an old outhouse and if you looked down you would see a year’s worth of shit.

The houses in the area were pretty well spread out. There was no real plan. When someone had a piece of land, they built on it and every house looked different. Some people could only afford a certain amount of building material, so if they didn’t have enough money they would have to wait until the next time they got paid, then they would buy more materials to finish off the house. Some houses took many years to complete.

There were two mango trees in our front garden and other fruit trees around the side and back. These gave us star apples (a sweet, black fruit), gooseberries, carambola (also known as five finger fruits in Guyana), awara, sapodilla and breadfruit.

Looking back now, people had a hard life in Guyana in the 1960s and ’70s, but we didn’t perceive it as such. You couldn’t get potatoes or some tinned goods due to a ban on certain imports. Forbes Burnham, the prime minister during that period, as a student in London, had known Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, Michael Manley of Jamaica and other political figures who went on to become leaders of newly independent countries of Africa and the Caribbean.

I remember the first time I saw an apple. My uncle brought one home; I don’t know where he got it. He cut it up and shared it so that everyone could have a little taste. While I never went hungry, there were basic foodstuffs that you simply couldn’t get.

My mum Patricia was young, fit and athletic, and, boy, could she run – bad news for me, as she could always catch me. Many times, I ran knowing that I was in trouble. I would get some way down the road before I felt her hands on my shoulders. Holding me with one hand, she would smack me with the other while I did a little dance in a futile attempt to avoid the blows. I suppose it must have been comical to people watching, but if it was my turn today then it would be one of my friends tomorrow. This was fairly routine for young boys growing up in our community.

There was a massive oil refinery at the end of our street and sometimes we would find very large oil drums. Cut lengthways, we found that they floated quite well and could be used as a boat along the Demerara River; we did this with abandoned car tops as well. All the huge tankers used to come up the Demerara and we would paddle to the massive boats. This was probably not the best idea, particularly as neither of us could swim – take on a little bit of water and it would have been all over.

Of course, with any prank like that, word got straight back to my mother. She would know what I had been up to before I got home and so there would inevitably be trouble. By the time I was only halfway home, I could hear my mum calling – oops, somebody had seen us! – and I could tell by the tone in her voice that she wasn’t happy. I walked down Water Street contemplating my fate, knowing I had to go home. I went in and my mum came towards me and as usual I made a run for it. It wasn’t long before she had caught up with me, but even I, at that young age, thought I was due for some punishment.

But by the time I was 8, I could run faster than my mum and she could no longer catch me. One day, I was making a run for it when I reached the point where she usually caught up with me, but this time she hadn’t. I looked around and mum was standing in the middle of the road gasping, out of breath. It was the first time I had been able to get away.

I remember these moments with fondness and laughter. The young, feisty West Indian lady is, these days, wrapped around the fingers of each and every one of her grandchildren, nothing but gentleness left.

Discipline was firm in those days and coupled with religious beliefs meant that as a child you were simply judged on how well you followed a grown-up’s orders. My father was a preacher, so I had religion at home, but as he was currently far away my gran, a religious woman, picked up the reins, the Bible and its teachings always close at hand.

School was intermittent, as I was taken out of school because I would soon be going to England. The entire education system was British. Everything you heard about England was great, so standards of discipline and good behaviour had to be high. From an early age I was imbued with English values, and when I say English values, these were the perceived English values of the time. Although I feel very West Indian, many West Indians would think I was very English.

I remember my very first day at school where we all had to stand up and introduce ourselves to our classmates, saying our names. I rose to my feet and announced that I was Clairmonte. The whole class laughed, 5-year-olds can be tough. By morning break, when questioned about my name again, it had miraculously changed to Chris, my middle name, which seemed more acceptable. From then on, I was always Chris.