17,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crown House Publishing

- Kategorie: Bildung

- Sprache: Englisch

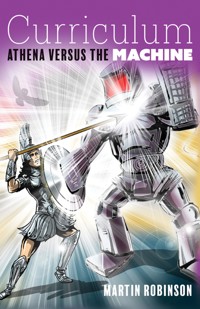

Martin Robinson's Curriculum: Athena versus the machine explores the educational value of a curriculum rooted in the pursuit of wisdom and advocates the enshrinement of such a curriculum as the central concern of an academic institution. Rather than being seen as a data-driven machine, a school should be viewed as a place that enables children to develop thoughtful perspectives on the world, through which they can pursue wisdom and be free to join in with the ancient and continuing conversation: 'What is it to be human?' Teachers need to be liberated from policy-led prescription in order to design curricula which bring the subjects being studied, rather than the blind pursuit of measurable outcomes, to the foreground of the school's teaching and learning agenda. In Curriculum, Martin Robinson explores how this can be achieved. The Machine demands data, order and regulation; Athena is the goddess of philosophy, courage and inspiration. An Athena curriculum celebrates wisdom and skills, and considers why it seeks to transmit the knowledge that it does. In this book, Martin examines how we can construct a curriculum that will allow liberal education to flourish. Anti gimmick and pro wisdom, the principles that he advocates will make a big difference to teachers' and pupils' lives, and will help to ensure that our young adults are better educated. Suitable for teachers, school leaders and policy makers.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Praise for Curriculum

In a period in which the curriculum – and even the very purpose of education – is subject to ceaseless challenge and accountability, this welcome book overtly opens up the debate. Martin Robinson paints a picture of an education system in thrall to the Machine: a data-obsessed, narrowly instrumentalist, capitalist version of education, wherein metrics are cherished more than wisdom. However, passionate as he is for a liberal, dialogic curriculum, Robinson does not simply wish us to agree, or to succumb to his view, but rather to critically engage. And Robinson’s assertions have relevance beyond schooling, given the recent onslaught of instrumentalist applications to higher education too. Whether you agree with his arguments or not, you will not fail to be stimulated by Curriculum.

Professor Becky Francis, Director, UCL Institute of Education

In this learned and accessible book, Martin Robinson explores the tensions at the heart of curriculum thinking – pointing to wisdom and the structures and systems likely to hinder it. Robinson tackles the reductionist, misconceived view of a knowledge-rich curriculum as a series of lists and urges us to regard it as a way of making meaning, of asking serious questions about how we live, of thinking about the values, ideas and objects that help to shape our lives and the larger landscape of human endeavour.

An important read for all school leaders.

Mary Myatt, author of High Challenge, Low Threat and The Curriculum: Gallimaufry to Coherence

This is a very important book. While the dumb and brutal ugliness of instrumentalist education is all too familiar to many of us, never before has it been so clearly expressed or so convincingly unpicked and exposed. Martin Robinson’s Curriculum, however, is much more than a depressing, defeatist explanation of why things have got as bad as they are. Instead it is a beautifully written love letter to the very substance of education, a triumphant and confident call to arms, and is ultimately the manifesto on which the fightback against the Machine should be based.

Ben Newmark, Vice Principal, Nuneaton Academy

Martin Robinson’s Curriculum is an impassioned call to arms for educators to throw off the shackles of the Machine with its data-driven approaches and embrace a more human vision of education which puts the curriculum at its core. An astounding book on many levels which is destined to become the seminal work on what should be taught in our schools.

Dr Carl Hendrick, author of What Does This Look Like in the Classroom?

As the focus of our schools and academies turns to curriculum, in writing this book Martin Robinson has given us a timely paean to the polymath. Arguing that schools need to move beyond education as mundane transaction, Robinson imagines a broad and balanced curriculum designed to inspire and nourish wisdom.

Readable and uplifting in a way that many other contemporary education books are not, Robinson’s achievement is to take the recognisable and commonplace in our schooling system and reframe it in such a way as to place it on a higher plane, while at the same time retaining its familiarity.

Robinson is the grizzled, eccentric and entertaining teacher in the corner of the country’s staffroom: challenging assumptions, refusing to toe the line and with no time for the bright young things and their data-laden tablets. His is a much-needed voice of dissent in an era of mechanistic education.

Duncan Partridge, International Programme Development, Voice 21, and former director of education, The English-Speaking Union

Appealing both to teachers nervous of a return to Gradgrind’s ‘facts alone’ and those troubled by the romantic ideals of progressivism, Robinson’s Curriculum lays out with crystal clarity the questions confronting schools and their leaders in the aftermath of the turn away from a skills agenda and back to knowledge. Like a Virgil in tweed, he leads us on a fascinating journey down the corridors of our corporategrey schools amid their perils of spreadsheets, tick-boxes, technology and bureaucracy – and shows that unless teaching and learning are understood as quests for human freedom, curriculum risks becoming yet another buzzword fad.

In a work infused with the same remarkable breadth of reading and grasp of detail that made Trivium 21c such an accessible but intellectually rich work, Robinson deftly sets out what school leaders, teachers, pupils and their parents must do if we are to discover the knowledge that will make us all wise.

Gareth Sturdy, teacher, journalist and co-author of What Should Schools Teach?

Curriculum is a timely, refreshing and enlightening follow-up to Trivium 21c. At a time when thousands of schools across the UK are wrestling with the challenge of curriculum design, all too often with a vision limited by the pressure to maximise outcomes, Martin Robinson leads us to the philosophical high ground – and it’s a mighty relief.

The central metaphor of Athena versus the Machine captures the state of things perfectly, serving both as a warning and a call to arms. Tackling a broad range of issues – including whether knowledge can or should be ‘powerful’, the concept of cultural mobility, and the role of formal education in the context of educating for freedom – Martin reminds us continually that, far from the utilitarianism of the machine, education is deeply human and that knowledge ‘helps us to understand who we are’. Martin challenges us to raise our sights, to think more deeply and expansively about the purpose of the curricula we provide and to remember who it’s all for.

Intellectually, Curriculum towers above the field of functional books about schooling; a must-read for anyone looking to put some heart and soul into their curriculum.

Tom Sherrington, education consultant and author of The Learning Rainforest and Rosenshine’s Principles in Action

In his latest book, Martin adds to his earlier work on the Trivium and discusses the difference between a curriculum which serves ‘Machine schools’ and one which serves ‘Athena schools’. His theory is that while it is essential to provide a knowledge-rich curriculum, it is the quality of the knowledge that matters. He goes on to ask difficult questions about who decides what a non-white, non-middle-class curriculum looks like, and makes the point that liberal arts are not set in stone and that tradition is ever-changing.

At a time when Ofsted (themselves a cog in Robinson’s Machine analogy) has reignited the curriculum debate, Curriculum is a most timely publication and a thought-provoking read for anyone involved in our current school system.

Naureen Khalid, trustee of Connect Schools Academy Trust and governor on the local governing body of Newstead Wood School

In Curriculum, Robinson explores what contemporary educational debate has sorely needed: a way to give real meaning and purpose to education beyond its mere capacity to generate wealth or power.

Michael Merrick, teacher, writer and speaker

In Curriculum, Martin Robinson tackles the central educational issue of our time: the contest between Athena (the goddess of wisdom) and the Machine (mechanical thinking and the quantification of learning). He reminds us, however, that the beating heart of the school lies in its curriculum, and assures us that there is still hope for ‘bringing the human back’ into education.

Written with Martin’s customary elegance, wit and intelligence, Curriculum is an inspirational contemporary hymn to the teacher, warning us off settling for the click of the Machine when Athena beckons us to rediscover an education that gives meaning to life. It’s destined to be one of the must-read books in the field.

Paul W. Bennett, Director, Schoolhouse Institute, Founding Chair, researchED Canada, and author of ten books on Canadian history and education

Written with meaning and human purpose – and with erudition, compassion and a real understanding of ground-level pressures facing the school machinery – this is the best book on curriculum that I have read. And at a time when curriculum as a concept and reality are up in the air across the UK, and moving in divergent directions, this is the text that brings us together in terms of what’s really important in education, and what binds us. It needs to be read by everyone with a stake in our future.

Rajvi Glasbrook Griffiths, Deputy Head Teacher, High Cross School, Director, Literature Caerleon, and writer for The Western Mail, Planet and Wales Arts Review

Curriculum is a wonderfully inspiring, optimistic and deeply philosophical book that refocuses the purpose of education. Martin’s style of writing and philosophical considerations are fascinating in provoking our thinking about the value of education and the reasons why we, as educators, come to work every day.

A must-read for educators, yes, but also for anyone who values the centrality of education in the pursuit of wisdom and the betterment of humanity.

Sam Gorse, Head Teacher, Turton School

To Olive, Kerry and Lotte, with love.

Contents

Acknowledgements

I must thank the following people who have helped this book see the light of day:

David Bowman for his patience and kindness; Peter Young and Emma Tuck for seeing the book through its gestation with wise counsel and great care; Beverley Randell for thoughtfully and diligently keeping me on my toes; Rosalie Williams, Tabitha Palmer and Daniel Bowen for their encouragement and ideas; Tom Fitton for his wonderful cover design; and, indeed, everyone at Crown House for sticking with this project throughout.

Thank you also to Tom Sherrington, Sam Gorse and Gareth Sturdy, and my mum, for their comments on the first draft, which helped me sharpen my focus and understand the whole book from fresh and different perspectives.

Finally, and importantly, my family and friends, who have helped more than they can know over a challenging couple of years, thank you.

Yes, ’twas Minerva’s self; but ah! how changed,

Since o’er the Darman field in arms she ranged!

Not such as erst, by her divine command,

Her form appeared from Phidias’ plastic hand:

Gone were the terrors of her awful brow,

Her idle aegis bore no Gorgon now;

Her helm was dinted, and the broken lance

Seem’d weak and shaftless e’en to mortal glance;

The olive branch, which still she deign’d to clasp,

Shrunk from her touch and wither’d in her grasp;

And, ah! though still the brightest of the sky,

Celestial tears bedimm’d her large blue eye:

Round the rent casque her owlet circled slow,

And mourn’d his mistress with a shriek of woe!

Lord Byron, ‘The Curse of Minerva’ (1812)

Introduction:

The Athena School

A god in the sense I’m using the word is the name of a great narrative, one that has sufficient credibility, complexity and symbolic power so that it is possible to organise one’s life and one’s learning around it. Without such a transcendent narrative, life has no meaning; without meaning, learning has no purpose.

Neil Postman, The End of Education (1996)

The ‘great narrative’ of too many of our schools is mundane, with the merely measurable as the pinnacle of meaning. Counting them in, counting them out; these schools employ mechanical metaphors. Each child is set on a ‘flight path’, and data and targets are worshipped rather than the symbolic, spiritual power of a god. Perhaps this is inevitable in a secular world, but is it wise? These schools bypass the quality of knowing something and replace it with destination data – knowledge is a means to an end rather than an end in itself. The focus is on the grade and not on the knowing.

Knowing is essential, it is the stuff of education, but what to know, why to know it and how to know it are not only essential questions, they are also impossible to answer fully with any degree of certainty. Yet there are those who search for objective answers to these questions by allying education to the instrumentalism that is extant in large numbers of schools.

Some of these instrumentalist aims take the form of justifying certain content by suggesting that it is essential for social mobility and/or social justice. Others insist on a pragmatic approach that might provide a march up the school exam league tables. And others see success in counting the number of pupils who leave the school to enter a ‘top’ university. In many schools, pupils have gone from being potential citizens to customers of an educational product, and now find themselves reduced to data points with a need to perform beyond expectations for their ‘type’. Is this a meaningful pursuit? Whichever method is used to justify the content of a curriculum, can utilitarian/utopian aims (or their proxies) justify 13 years or so of full-time education?

This book argues for the study of knowledge for its own sake, but also that knowledge, alone, is not enough. Schools need to set up their pupils for the individual and communal pursuit of wisdom. This pursuit is animated by a god, Athena, while the overtly instrumentalist approach is represented by the Machine. While it is essential to provide a knowledge-rich curriculum, it is the quality of the knowledge that matters, and therefore it is within this subjective realm – where individual taste and thought is understood and nurtured, and the way we make meaning in the world matters – that the arguments in this book will be made. The qualitative approach will be set in direct opposition to the purely quantitative.

How does Athena help to provide us with the wherewithal to deliver a curriculum centred around the pursuit of wisdom?

Athena

Hephaestus wielded a giant axe and in one swift swing cut Zeus’ head clean in two. Then, as Stephen Fry explains in Mythos (2018: 84–85), out stepped a female: ‘Equipped with plated armour, shield, spear and plumed helmet, she gazed at her father with eyes of a matchless and wonderful grey. A grey that seemed to radiate one quality above all others – infinite wisdom.’ Zeus’ head repairs itself, and all who witness the birth of Athena realise that she has power beyond all other immortals.

Nietzsche (1969 [1883–1891]) pronounced that ‘God is dead’ and foresaw our struggles to create meaning. Without meaning, the school – the very place in which we should aspire to learn about the greatest thoughts and ideas – becomes the place where purpose is reduced to a list of target grades and performance measures that offer little in the way of true inspiration: the transcendent.

Athena has inspired many people across continents and civilisations, and now, most importantly, she can inspire us. Instead of asking what do the exam boards want, what does government want, what does the customer want, what does the market want, what do inspectors want, what does the data demand, we can aim higher: what does Athena want? What can Athena bring to our schools?

Athena is the goddess of philosophy, courage and inspiration. She is concerned with promoting civilisation and encourages strength and prowess. She brings order but can also rustle up a storm. She is the goddess of mathematics, strategy, the arts, crafts, knowledge and skills. She is the goddess of agriculture, purity, learning, justice, intelligence, humility, consciousness, cosmic knowledge, creativity, education, enlightenment, eloquence, power, industry and inventions – scientific, industrial and artistic. She is the patron of potters, metalworkers, horsemanship, women’s work, health, music, navigation and shipbuilding. She is virginal but imbued with maternal cunning. She possesses magical powers. She is the protector of the state and social institutions. She is a teacher of many things, including working with wool. She is the goddess of law and just warfare. She is not afraid of a fight (she flayed the skin of Pallas and used it to make a shield) and can inspire others into battle. But she is able to put down her weapons when necessary because she is not driven by war. Athena is the goddess of wisdom.

Looking around at what some of our schools have become, we can see that wisdom has been sidelined. When the importance of knowledge is reduced by becoming part of an input–output model of measurable ‘success’, there is a need to move from the mechanistic systems that have caused this decline in value and to bring the human back in. Our attitudes and perspectives towards knowledge matter. The meaning we give to it matters – and the meaning it gives to us. If we think of curriculum as narrative, and realise that our stories are understood in many different ways, we begin to understand that being knowledge-rich is also about the many ways that knowledge is understood. These understandings are tied into value systems and the ways in which each of us makes meaning and that meaning is revealed to us. Curriculum, at its heart, can challenge us to reassess our values and understand meanings anew.

A curriculum that serves Athena is a very different beast to one that serves the Machine. An Athena approach to curriculum is an education that unashamedly pursues wisdom and extols the virtues of why to study. It asks, ‘Children, do you want to be mind-full or mind-less? A free person or a slave?’ Some might choose mindlessness – the easy, cynical way – but if we are to make a real difference to human lives then we should be offering more. Education can help to free us, and this freedom is first and foremost a freedom of thought.

The Greek creation myth involves Prometheus making human beings by shaping them from small lumps of clay. Athena breathed life into these figures – giving them their potential for wisdom and feeding their souls. A mechanical education works against freedom of thought, while Athena positively nurtures it. This is the joy of a liberal education.

A liberal education is shaped by its pursuit of wisdom, whereby the teaching and learning of knowledge are joined by the nurturing of experience and judgement. For the philosopher Michael Oakeshott (1989 [1975]: 22), ‘Liberal learning is learning to respond to the invitations of the great intellectual adventures in which human beings have come to display their various understandings of the world and themselves.’ It is, above all, an invitation to join in with the conversations that began at the beginning of time and that will continue long after our individual lives have ended. This is where the pursuit of individual wisdom interacts with and becomes enlivened by our communal, continual pursuit of wisdom.

If we decide to make this pursuit our central mission, how would it change our schools?

Part I

The Machine

Chapter 1

The Knowledge-Rich Curriculum

‘We all teach knowledge’ is one of the phrases used to argue against knowledge-rich approaches. It is easy to see how a problem might arise – indeed, we do all teach knowledge.

In many people’s pockets and on many people’s desks, a knowledge-rich environment is but a tap or a click away. There is a lot of knowledge out there on the internet and in the library; there is more easily accessible knowledge than anyone could learn in a lifetime. Knowledge is everywhere.

If by knowledge-rich we mean ‘a lot of knowledge’, it can easily be argued that each child could google to their heart’s (and mind’s) content every day, make changes to their long-term memories and tick the knowledge-rich box. But this would be facetious. A disorganised romp through ‘facts’ of varying degrees of veracity thrown up by a search engine is not a curriculum.

What makes knowledge rich is how it is organised. Knowledge is organised into subjects and disciplines which have their own ways of interrogating the world. It is organised by values – how we feel about the world and what is important to us. It is organised by narratives within and across subjects and disciplines which can open up arguments, clashes and disagreements on which people often pitch their identities. Knowledge is the stuff we marshal to help us find a place in this world; hence why the potential answers to ‘what knowledge?’ are so keenly felt.

Which is why knowledge on its own is not enough. Curriculum is the organisation of knowledge. It should help children to understand different ways of making meaning and how values enable us to respond to the world. Knowledge-rich is not rich at all if it fails to demonstrate the importance of the great controversies that allow human beings to argue about how we live and how we might live.

Educational approaches that use (so-called) purely objective data to justify the type of education a child receives falter because the very ground on which they stand tends not towards wisdom but the easily measurable. Whether these quantifiable measures are test scores, destination outcomes, average wage achieved or IQ, they will struggle to explain why a young person should study Antigone rather than We Will Rock You, other than implying that Antigone is somehow more ‘acceptable’ because we might find it referred to in a broadsheet newspaper. But We Will Rock You might be found there too, so this doesn’t get us very far.

Some of the more astute among you might be shouting, ‘We should study the things that engage our kids and are meaningful to their lives,’ and that might be true, but what these things might be is not immediately apparent to any of us. What is ‘meaningful’ and, thereby ‘truly engaging’ to a life is not revealed instantly. It can take a lifetime of searching to find out that something we thought we knew can speak to us in an entirely new and enlightening way.

What we understand by ‘knowledge-rich’ and ‘broad and balanced’ in order to justify what we include – and what we leave out – matters. It matters because this is what helps to engage young people in making meaning in their lives, and this cannot be achieved with shallow, instantly gratifying, isolated chunks of information.

Whose knowledge, what knowledge and why are important issues, not just for theoretical debate, but as urgent questions that demand answers. Arguably, it was Matthew Arnold who set us on this course: he regarded certain knowledge as ‘sweetness and light’, as opposed to philistinism or barbarism (Arnold, 2009 [1869]). Whether the argument is ‘knowledge is power’ or ‘knowledge is powerful’, each agenda tries to justify itself in ways beyond the idea of what knowledge is best to know on its own terms. That those who have been educated about the finest things sometimes commit the grossest acts shows us that not all is sweetness and light in the knowledge stakes.

But if Arnold’s approach is mistaken, is the only alternative on offer the philistinism of the marketplace, whether measured by exam scores or five stars on Amazon or Goodreads? A TripAdvisor approach might work for choosing a hotel for a two-week vacation in sunny Spain, but can we rely on popular choices to discern beauty and truth beyond what is immediately accessible? If we devalue the role of the curator and the connoisseur – and leave curriculum in the hands of populists, the market, exam scores and arguments around accessibility – then teachers really have given up.

What does this mean in practice? It means, without a doubt, that the curriculum should include Antigone and not We Will Rock You. This decision is shaped by our values, and Athena can help us realise what those values are. It is the quality inherent in what-is-to-be-learned that answers our questions about what to include. And yet, quite rightly, it also opens us up to many arguments. Prejudice, authority, tradition and intuition are very difficult to muster if they are the only ammunition you have on your side. This is again why knowledge alone is not enough. Making a list of things to be learned is a dispiriting task; many a reductive approach to curriculum design starts and ends with these lists. If we can glimpse something beyond the list – the cultural assumptions, arguments and structures of our storytelling – we can begin to understand what a good curriculum might be. This book argues that culture is an essential way that humankind makes sense of and engages with the world, and it is our duty to our young people to help them in this sense-making and engagement.

It might be that teachers can’t explore these issues because they are trapped within mechanistic approaches. They might be preoccupied with data and test scores, obsessed with quantitative rather than qualitative measures. They might pay lip-service to quality but find themselves teaching in schools obsessed by systems. These schools, although often called ‘factory schools’, are more akin to ‘office schools’ and define themselves through varying degrees of accuracy and efficacy (‘look at our score’).

Athena cannot necessarily make children wise, but she can set them on the pursuit of wisdom and help them to develop their minds in tandem with the wisdom(s) of the time. Whatever we inherit genetically, it is what we come across culturally and socially that helps us to understand what we are and what we might be.

The mind is not an empty vessel awaiting knowledge: children come to school already equipped with stories and ways of making sense of the world. Curriculum can only make inroads into pupils’ minds if we accept that some of what we teach is highly contested – challengeable as well as challenging. It is only by getting involved in these contestations that we can set our pupils’ minds on the path towards wisdom. And we shouldn’t just focus on the individual. Instead, we should also look at the community of minds as a whole and pursue wisdom as a collegiate affair.

The pursuit of wisdom is one we hold in common. It is a contract between the living, the dead and the unborn. It is either enhanced or degraded in our culture, institutions, schools and classrooms. Curriculum is not asking how well one child is performing, but how wise our studies are. If our pupils as a whole strike us as culturally impoverished, we have to ensure that our school culture enriches, broadly and deeply. We have to attend to our curriculum: is it rich enough? Is what we teach good enough?

However, the Machine is just a click away. It systematises, rather than humanises, by treating the human being as a measurable memory machine: pupils are reduced to ‘programmes on computers made of meat’ (Midgley, 1994: 9). They are components of an input–output system which focuses only on the extremely important aspect of memorisation, at the cost of the rather more qualitative ‘why’ or ‘what is important’– on feelings, taste, discrimination, argument, thought, educated opinion and being able to express ourselves. If we simply view learning as being ‘brain based’, a mechanistic metaphor that leaves out the human being, then our education system will leave young people struggling to make meaning of their lives.

This book is partly a hymn to the teacher; instead of being seen as erstwhile office workers, with ‘teaching’ entailing delivering on the bottom line, Athena wants to re-energise the teacher as a member of the community of minds from which they emerged and into which they can introduce their progeny. This is why we went into teaching. This is our necessary mission.

But this is not possible if the teacher is caged inside the Machine.

The Iron Cage

Human nature is not a machine to be built after a model, and set to do exactly the work prescribed for it, but a tree, which requires to grow and develop itself on all sides, according to the inward forces which make it a living thing.

John Stuart Mill, On Liberty (1859)

In their ‘Teacher Well-Being and Workload Survey: Interim Findings’ (Scott and Vidakovic, 2018), Ofsted found that: