10,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

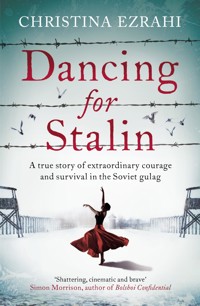

- Herausgeber: Elliott & Thompson

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

___ An innocent woman sent to the Gulag. A passion that gave her the will to survive. 'Shattering, cinematic and brave' Simon Morrison, author of Bolshoi Confidential ___ Nina Anisimova was one of Russia's most renowned ballerinas and one of the first Soviet female choreographers. Yet few knew that her exemplary career concealed a dark secret. In 1938, at the height of Stalin's Great Terror, Nina was arrested by the secret police, accused of being a Nazi spy and sentenced to forced labour in a camp in Kazakhstan. Trapped without hope – and without winter clothes in temperatures of minus 40 degrees – her art was her salvation, giving her a reason to fight for her life. As Nina struggled to survive in the Gulag, her husband fought for her release in Leningrad. Against all odds, she was ultimately freed and astonishingly managed to return to her former life, just as war broke out. Despite wartime deprivation and the suffocating grip of Stalin's totalitarian state, Nina's irrepressible determination set her on the path to become an icon of the Kirov Ballet. A remarkable true story of suffering and injustice, of courage, resilience and triumph. ___ 'Nina Anisimova's story is extraordinary – heroic and harrowing in equal measure, a snapshot of the best and worst of Stalin's Russia – and Christina Ezrahi does it vivid, gripping justice.' Judith Mackrell, author of The Unfinished Palazzo 'Christina Ezrahi vividly charts this brutal and uplifting story, bringing alive an extraordinary resourcefulness and determination to survive.' Helen Rappaport, author of The Race to Save the Romanovs 'Christina Ezrahi has uncovered a remarkable, untold episode in Soviet ballet history, which she brings to life through her customary rigorous research, clarity of expression and elegance of prose.' Baroness Deborah Bull 'An inspiring tale of survival against the odds. Ezrahi's diligent scholarship casts much-needed light on ballet history's darkest chapter.' Luke Jennings, dance critic and author of Killing Eve

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 544

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

‘Shattering, cinematic and brave, Ezrahi’s expertly researched biography of ballerina Nina Anisimova describes, in deeply personal terms, a star of the cruellest art overcoming the cruellest political system. An astonishing book.’

SIMON MORRISON,AUTHOR OF BOLSHOI CONFIDENTIAL

‘Christina Ezrahi has uncovered a remarkable, untold episode in Soviet ballet history, which she brings to life through her customary rigorous research, clarity of expression and elegance of prose. It is an account of how one artist is forced to draw on her dancer’s discipline, determination and focus to survive circumstances of unimaginable physical challenge and emotional and psychological deprivation. Yet it is also the story of how, even in the most dehumanising of situations, art provided a lifeline, connecting her back to her former self, her dignity, to beauty and joy and, unexpectedly, onwards to a celebrated career in dance. Some of us will know the name Nina Anisimova as the choreographer of Gayané and a distinguished artist at the Kirov Ballet; none of us will have imagined that the two-year gap in her CV hides a story far more astonishing than any she would ever portray on the stage. This book is that story.’

BARONESS DEBORAH BULL

To Ariel, Lina and Yariv

‘What do you feel when you are performing foryour executioner?’ ‘Actually, the whole countrywas performing and dancing for Stalin.’1

Lazar Shereshevsky, poet, translator and former prisoner andcamp performer (Beskudnikovsky corrective labour camp).

CONTENTS

Map of the USSR

Introduction

1 The Arrest

2 Nina

3 Enemy of the People

4 The Confrontation

5 The Journey

6 The Kazakh Steppe

7 The Folly of it All

8 Dancing Behind Barbed Wire

9 The Return

10 The Great Patriotic War

11Gayané

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

A Note on Proper Names and Translation

A Note on the Source Material

Notes

Selected Bibliography

Index

INTRODUCTION

I stumbled upon the Stalinist nightmares of Nina Anisimova by accident. One autumn morning, sitting at a large desk in the reading room of a St Petersburg archive, I stared uneasily at a document folder that should never have found its way into my hands. Outside, people wrapped up in coats and hats were rushing down Nevsky Prospekt and climbing on to crowded trolleybuses, the Admiralty’s golden spire etched against the bright sky. Nearby, dance students were walking with turned-out steps towards the heavy wooden entrance doors of the world-famous Vaganova Academy of Russian Ballet.

While working my way through the private papers of a Stalin-era ballerina, I had ordered up a file from the archival depository because its title intrigued me – it contained an ominous reference to contact between Soviet artists and foreigners in the terrible year of 1938. The librarian had overlooked the clear instructions on the file’s title page that the folder should not be handed out to researchers without special permission. A slim folder holding several sheets torn out of a school notebook was now lying open in front of me. On every sheet, written in neat Cyrillic cursive, were denunciations.

From July 1937 until November 1938, Joseph Stalin and his henchmen had directed one of the most murderous campaigns of a modern state against its own citizens, a campaign that is now known as the Great Terror. Day after day, the dictatorship’s propaganda machine announced that spies, saboteurs and enemies of the people were hiding everywhere, in plain sight. Ordinary Russians listened in astonishment to the disclosure that even the highest levels of government and the military had been infiltrated. Arrests and mysterious disappearances of citizens from all walks of life plunged the entire Soviet empire into an abyss of fear and suspicion.

The denunciations that I was looking at had been written in 1938 by a young ballerina. Her reports incriminated around three dozen dancers, actors and conductors, including some of the most important names in Soviet cultural life. All these artists, according to the reports, had supposedly been in regular contact with foreigners from enemy nations such as Germany and Japan, an accusation that in Leningrad in 1938 could lead to arrest and a death sentence for espionage. It was unclear whether the ballerina had written them under duress or voluntarily; the longest reports in the file were about her own actions, implicating others in her attempt to justify her behaviour, and listing gifts she and others had received from foreigners several years previously. She was protesting her innocence, emphasising that she had since broken off all contact with her foreign acquaintances.

Such denunciations were common during the Great Terror, and a sad reality of Soviet life: by 1938 the NKVD, the Soviet secret police, had enlisted a spider’s web of informers that linked it to virtually every communal flat and all Soviet institutions. Whether out of fear, malice or loyalty, informers fed a never-ending stream of incriminating information to the security services. The NKVD also routinely cornered people into denouncing others during their interrogations. The fact that a leading ballerina had written denunciations at the height of the Great Terror was therefore not surprising. But the fact that the reports had not been destroyed but had been preserved among the ballerina’s private papers through the siege of Leningrad, the end of the Second World War and the collapse of the Soviet Union, and now found themselves in my unsuspecting hands seventy-five years later, was completely extraordinary.

The file contained one document in particular that sent a chill down my spine. Written neatly on two connected sheets, it was a list of thirty-four names which gave each person’s age and professional affiliation. It consisted primarily of dancers, including the Kirov Ballet’s entire upper echelon but also several actors and two famous conductors. The thirty-four artists had apparently all been guests at the home of an employee of the German consulate in Leningrad, the legal consultant Dr Evgeny Salomé.

As my eyes raced down the list, I felt transported back in time to a point in Russian history when individual destinies were like dots on a dice, shaken and cast by the NKVD in a game of life and death. The very existence of this list could have destroyed a generation of leading ballet dancers and conductors, potentially changing the course of Soviet cultural history. But while all the other reports bore no obvious signs of external influence, a stranger’s hand had scribbled comments on this one – eleven names had been neatly ticked off, six others crossed out and a new one added in handwriting that was different from the ballerina’s. I was aware that many of the artists whose names had been ticked had lived long and successful lives, but I did not recognise any of the names that had been crossed out, except for one: the Kirov Ballet’s legendary character dancer Nina Anisimova.

The image of the crossed-out names burned itself into my mind. It marked the beginning of a quest to find out what had happened to the dancers of the Kirov Ballet during the Great Terror of 1937–8. As I dug deeper into archives in St Petersburg and Berlin, a surreal story started to emerge: of fabricated and genuine German spies, of innocent dancers and other artists who had been executed, their bodies dumped in mass graves, their memory erased. I began to focus my efforts on the mysterious fate of the list’s most prominent name, Nina Anisimova, whose official biography appeared untarnished despite her name having been crossed out.1

Would I be able to unravel the secret story of Anisimova’s life?

1

THE ARREST

Nina Anisimova put on her low-heeled character dance shoes and straightened herself. She twisted and turned in front of the mirror in her changing room at Leningrad’s Kirov Theatre, checking her costume and make-up. She was about to perform the part of the Basque woman Thérèse in Vasily Vainonen’s ballet The Flames of Paris, a work written to glorify the French Revolution. Created six years earlier to celebrate the fifteenth anniversary of Russia’s October Revolution of 1917, it had become one of Stalin’s favourite ballets.1

Framed by the high arches of her eyebrows, Nina’s expressive brown eyes burned with a fire appropriate for her tempestuous character. Her dark hair was kept in place by a white scarf knotted at the nape of her neck, its long ends trailing down her back. The bodice of her sleeveless dress softened into a blue volante, which was layered over a red skirt cut to give the illusion of a ragged hem. A rust-red shawl was thrown over her shoulders and tucked tightly into her belt. She tossed back her head, pumping her arms like a runner while pounding her heels in a rapid staccato rhythm. She stopped as abruptly as she had started, and checked her reflection in the mirror. Her costume had withstood the test and everything was still in place: she was ready to go on stage.2

The third act of The Flames of Paris was about to begin. Standing in the wings, Nina focused all her energy on transforming herself into Thérèse, a simple woman burning with hatred against France’s ancien régime. After the October Revolution, Russia’s own revolutionaries had attacked classical ballet as frivolous after-dinner entertainment conceived to dazzle the imperial family and tsarist elites. They had declared that, in order to survive in a state trying to build Communism, ballet would have to abandon fairy-tale princesses in favour of a social conscience. Nina’s explosive performances as the revolutionary heroine Thérèse had played a central role in turning The Flames of Paris into a popular triumph of the nascent Soviet ballet.

Nina had worked hard to internalise the realistic acting method promoted by the Russian director Konstantin Stanislavsky. Her colleagues knew that sometimes Nina would get herself into such a state before her entrance that she would run on to the stage, shouting impulsively ‘After me!’, as if she were a revolutionary about to lead a popular uprising rather than a dancer performing in one of Russia’s most venerable theatres.3

The conductor took his stand, and the rousing melody of ‘La Marseillaise’ began. The theatre’s pre-revolutionary trompe l’oeil curtain with its gold-embroidered blue folds opened, revealing a Parisian square filled with workers, artisans, women, Jacobins and detachments of volunteers from France’s regions, preparing to storm the Tuileries Palace. Suddenly trumpets started to play, accompanied by the insistent pounding of drums. Two Basque men jumped into the centre of the stage and were joined by a third, their bodies as tense as tightly strung bows. Facing each other, they exploded into an impulsive dance, throwing their bodies into virile poses, their feet pulsing intricate rhythmical patterns as if the stage itself were a drum. Linking arms, they spun around, precariously balancing off each other’s weight before jumping up, their arms raised high into the sky and their fingers spread wide, a call to rebellion.

All of a sudden there was Nina as Thérèse, joining the dance of the men, the piercing staccato of which changed into a lilting but equally passionate melody. With tiny but rapid steps Nina seemed to float from one side of the stage to the other, her arms circling through the air as if she were drawing aside a curtain to look into a brighter future. Suddenly she leaned back as far as gravity would allow. Turning her face to the audience, she seemed electrified as she deftly began to move backwards, her heels pounding the stage. Later on the audience would be on the edges of their seats, ready to jump up as they watched her among the vanguard of the revolutionary masses storming the Tuileries. Holding high the tricolour flag, her frenzied eyes full of revolutionary fury, her face contorted as she was struck by a bullet. Sinking to the floor, she passed the tricolour flag to one of her comrades, dying a martyr to the revolution.4

It was 12 January 1938. Filing through the large swinging doors into the theatre’s vestibule, some people were inadvertently slowing down their steps, as if reluctant to leave the brightly lit magic of the theatre for the dark outside. Dispersing through the winter night, many could feel a chill returning to their bones that had nothing to do with the low temperatures. Since the summer, the nights had been filled with terror: people were disappearing. The NKVD’s dark cars, the Black Marias, or Black Ravens, were haunting the courtyards of Leningrad’s sprawling apartment buildings until the early hours of the morning, collecting the newly arrested and delivering them to the city’s overflowing prisons.

While ordinary citizens and the new Soviet elite were having trouble sleeping, the work never seemed to end inside a monumental building on Liteyny Prospekt, one of Leningrad’s central avenues, at the corner of Shpalernaya Street and a stone’s throw from the Neva River. Even years after the mass arrests of the Great Terror, many people dared to refer to the building only in a whisper: Bolshoi Dom, the Big House. Braver souls masked their terror by joking that the building was the highest in Leningrad because one could see Siberia from its cellars. Others would mutter a short verse to themselves:

On Shpalernaya Street

There stands a magical house:

You enter this house as a child,

But you leave it – an old man.5

The Leningrad NKVD had moved to its newly built headquarters in 1932, and the constructivist building loomed threateningly over the graceful, neoclassical buildings of imperial St Petersburg in its vicinity. Large blocks of dark granite formed an oppressive ground floor, its angularity emphasised by the square windows cut into the heavy stone. A plain portico framed the monumental doors leading into the building. On top of this massive base were seven further floors, a monotonous façade of narrow windows. The building was boxed in by a gigantic frame of dark stone that covered its windowless sides and flat roof, flanked on both sides by two towers of asymmetric heights. For the convenience of the NKVD agents, the Bolshoi Dom had been constructed next to the old tsarist prison on Shpalernaya Street, the infamous Shpalerka, officially, if euphemistically, known as the ‘House of Preliminary Detention’.* Opened in 1875 as Russia’s first prison for those under investigation, the Shpalerka’s beige building with its red ground floor consisted of a large square surrounding a central courtyard.

On 31 July 1937, Stalin’s Politburo began an operation that targeted the whole population, meticulously planning not only the elimination of real or imagined potential enemies but also setting specific targets for doing so. It commanded the arrest of 268,950 people, of whom 72,950 were to be shot and the rest sent to prisons or labour camps for eight to ten years.6

Initially, the massive operation was supposed to be completed within four months, in time for Stalin’s new constitution and the elections to the Supreme Soviet that were scheduled for December 1937.7 But ambitious local NKVD leaders saw the chance to demonstrate their loyalty and advance their careers and requested additional quotas; the deadline was extended again and again.

In Leningrad, Leonid Zakovsky was responsible for orchestrating the opening moves of this murderous campaign. A brutal opportunist, he liked to boast that he could have made Karl Marx confess that he was an agent of Bismarck.8 During the summer of 1937, the NKVD’s vast machine was working around the clock to compile arrest lists.

Zakovsky ensured that the terror quotas were exceeded – by the end of 1937, more than 19,000 people had been shot in Leningrad, almost five times the number demanded by the original order. Zakovsky was rewarded with a double promotion, but working for the NKVD was a dangerous profession and he did not have much time to enjoy his new status as head of the Moscow NKVD and deputy to the dwarfish NKVD chief Nikolai Yezhov, the grand organiser of the Great Terror: he was arrested by the NKVD in April 1938 and shot as a spy four months later.9

Zakovsky’s successor as head of the Leningrad NKVD was Mikhail Litvin, a protégé of Yezhov who had only joined the NKVD in 1936. A balding man with thin wire-framed glasses, Litvin would pre-empt his own arrest by committing suicide before the year was over. But on 31 January 1938, barely ten days after his appointment as head of the Leningrad NKVD, he examined the new quotas for Leningrad and the surrounding region: 3,000 people were to be shot by 15 March 1938, while 1,000 others were to be sentenced to forced labour or prison.10 More names had to be chosen.

CERTIFICATE

It has been established by the third department of the NKVD, that the inhabitant of the city Leningrad Anisimova, Nina Alexandrovna, born 1909 in Leningrad, Russian, citizen of the USSR, non-party member, ballet artist of the State Academic Theatre of Opera and Ballet named after S. M. Kirov, living on Kirov Prospekt, house 1/3, apt. 31, was a constant visitor of the German general consulate in Leningrad, being connected to the legal consultant of the German consulate in Leningrad – the established resident of German intelligence SALOME, on whose instructions she made acquaintances among Soviet citizens and she was recruited by SALOME for espionage on Soviet territory in favour of Germany.11

On the night of 2 February 1938 the winds were blowing across the Neva River, past the angel holding a cross atop the thin spire of the Peter and Paul Fortress. The Petrograd Side was the cradle of old St Petersburg, the site of the city’s unlikely foundation on swampy land. NKVD Captain Kokhanenko reached Lidval House at No. 1/3, Kirovsky Prospekt, a sprawling Art Nouveau apartment block constructed in the late nineteenth century, when the district was turning into one of the city’s most fashionable neighbourhoods. Unlike the standard layout of Russian apartment blocks with their maze-like backyards, the building’s wings were arranged around a courtyard open to the street – but this was not the moment to admire the building’s playful ornaments or the contrast between the decorative, undulating lines of the central block and the medieval motifs of the side wing.

It was long after dark, the most convenient time for arrests. The captain’s target was likely to be at home in bed, drowsy with sleep. He would be protected from the attention of bystanders during her arrest and subsequent journey to prison. Anyone still awake at that time would have frozen with dread as they heard the sound of an elevator, the creaking of floorboards, the ominous knock at the door. Led by the caretaker, the captain stopped in front of Flat 3.

Nina’s family had been living in this building since 1909, the year of her birth, but the family’s circumstances had changed drastically since the October Revolution. Before then, the Anisimovs had enjoyed the privileges that came with the successful military career of her father, Alexander Ivanovich Anisimov. Born in 1871 into a family belonging to the estate of hereditary ‘honourable citizens’ who enjoyed certain legal privileges, he graduated from the cavalry college attached to the Elizabeth Guards, joined the Imperial Army in 1892 and began to move up the ranks. At the turn of the century, the young captain fell for the charms of Maria Osipovna Alekseyeva, an artisan’s daughter who performed as a singer and dancer on the city’s variety stages. The couple soon had a daughter, Valentina, but, like many ambitious military men, Anisimov feared that marriage to a socially inferior performer would hinder his career and waited several years before marrying the mother of his child. In 1909 Nina was born, and Alexander Ivanovich continued to rise through the military ranks despite his marriage, reaching the respectable position of major general on the eve of the revolution.12

The Anisimovs lived a life of material comfort. Their household included several servants and a mademoiselle who oversaw the girls’ education. The family owned a small estate in Peterhof, outside St Petersburg, and holidayed in the Crimea and the French Riviera.13 But after the revolution the family was plunged into uncertainty and economic hardship. Anisimov voluntarily joined the Red Army, but was nonetheless briefly arrested by the Cheka* in 1918. As Petrograd descended into anarchy, he moved his family from their apartment in the city centre to Peterhof.14 When they moved back to the Petrograd Side a few years later, they had to readjust to the cramped reality of a communal flat. Anisimov worked as a military instructor until his retirement in 1927 and died in 1934 of typhus.15 Nina, her sixty-year-old mother Maria and her thirty-five-year-old sister Valentina continued to live among strangers thrown together by chance, involuntary witnesses to each other’s joys and tragedies.

The shrill doorbell shattered the night-time silence. The caretaker led the captain through the flat to Nina’s room and pointed at her:

‘Last name?’ asked the captain.

‘Anisimova.’

‘First name?’

‘Nina.’

‘Patronymic?’

‘Alexandrovna.’

‘Year of birth?’

‘1909.’

The captain compared the dancer’s answers to the information on the sheet in his hands. ‘Let us enter your room. Here is the search warrant.’16 Nina’s mother and the caretaker were ordered to act as witnesses for the ensuing search of her room. As the captain rummaged through Nina’s possessions, putting aside items to be confiscated as part of the investigation, the state tightened its iron fist around yet another individual. With the stroke of a pen, the NKVD had turned a twenty-nine-year-old dancer into a suspected enemy of the people.

In the early hours of 3 February 1938, Nina signed the first of many NKVD documents that would accumulate, page after page, in her NKVD investigation file. Intended to create an illusion of legal propriety, Nina’s signature on the search warrant attested that the search had been conducted properly and that no items had disappeared, apart from those objects confiscated as part of the investigation, including her passport, letters and photographs. The caretaker and the captain dutifully added their signatures; the time had come to call for the car that would transport Nina to prison.17

The dancer’s room was now closed and sealed by the NKVD. As Captain Kokhanenko led Nina out of the building and to the waiting Black Maria, mother and daughter had no way of knowing when, or if, they would see each other again.

The car took Nina across the Neva and along the embankment, past the ornate gates of Peter the Great’s Summer Garden, to the Shpalerka. She was told to get out of the car and wait while her police escort rang a bell. After a rattling of keys the heavy prison gates opened, then banged shut behind her. A long corridor loomed ahead, as in a surreal nightmare.18 One side was a row of narrow closets running down its entire length, the sound of muffled voices emanating from some of them.

Nina was led to one of the closets and locked inside it. Prisoners could sit on the narrow plank fixed to the rear wall, underneath a small light that dangled from the ceiling in a metal net. A female prison warder entered and ordered her to undress and hold up her hands. The warder’s coarse hands pulled back her ears, opened her mouth to see whether she was hiding anything in her cheeks or under her tongue, tipped back her head to check her nostrils, searched between her legs, and then focused on her pile of clothes. She cut off all the buttons, pulled out the belt and shoelaces and took away Nina’s hairpins and the elasticated girdle that had been holding up her stockings, a standard procedure to prevent prisoners from committing suicide. Female prisoners who wondered how they were supposed to walk with stockings slipping down to their ankles were told to plait their seams together to hold them up. Nina was now allowed to dress herself.

The warder ordered Nina to follow her, and they walked down a corridor and stopped in front of a cell. As Nina took her first steps into the bare room the key turned in the lock behind her. On a typical night that winter, there would have been around twenty-five to thirty women in the large collection cell that held the new arrivals, all arrested that night.19

Later, the warder returned and told the women to line up in pairs, their hands folded behind their backs. They were led down long corridors, shuffling along institutional walls, the bottom half painted an unpleasant shade of green, the top half whitewashed. Marching up the open staircase, they felt the claustrophobic weight of a tightly woven metal lattice enclosing the open space above the banisters, installed to stop prisoners from jumping to their deaths. The warder led the women into a prison bathroom, ordered them to untie their hair so that they could be checked for lice, hand in their clothes for disinfection and wash themselves under the showers.

From the showers, the new arrivals were marched down a corridor to be distributed among the Shpalerka’s 300 prison cells.20 For the first time they breathed in the prison’s distinctive stench, a suffocating mixture of sweat, fish, onions, damp, cheap tobacco smoke, excrement, urine and something else that was unidentifiable yet distinctive.21 While the cells varied in size, they were all hopelessly overcrowded. From the corridor they looked like cages holding wild animals, despite the heavy black curtains that covered the floor-to-ceiling steel rods. The warder stopped in front of one of them and turned the key. As the door opened, the foul, stuffy air of the overcrowded cell enveloped Nina.22

During the Great Terror, a large cell of forty square metres would have been crammed with about seventy women from all walks of life – young students, old women, doctors, housewives, intellectuals, engineers, fanatic Bolsheviks and internal émigrés. The cells’ large, barred windows overlooked the prison’s courtyard, their lower halves boarded up with wooden planks. A lavatory of sorts and a large red-copper sink occupied one corner, shelves for dishes the other. Long tables were arranged around the edges of the cell while narrow benches stretched along its walls. Near the door, several boxes lay on top of a large pile of long wooden planks.23

Like most new arrivals, Nina had no idea why she had been arrested. She should have been getting ready for daily class and rehearsals at the Kirov Theatre – five days later, she was supposed to perform at a major concert showcasing her interpretations of national dances from Georgia, Dagestan, Uzbekistan, Azerbaijan, Armenia and the Crimea at the Leningrad Philharmonic. Nina and her stage partner, Sergei Koren, had been working on this production for months.

Nina had conquered Leningrad’s highly knowledgeable and critical ballet audience not with the sparkling bravura or expressive lyricism of a classical ballerina, but with her artistic charisma and temperament, and her talent for Spanish, Russian, Eastern European and exotic national dances that were an intrinsic part of the city’s classical ballet tradition. She was a striking woman, auburn-haired with unusually expressive, piercing eyes and a volcanic temperament. Her overflowing love of life and her art spilled over into the Kirov Theatre’s turquoise-blue, white and gilded auditorium whenever the dancer burst from the wings on to the stage. It enveloped the spectators in their seats and made them feel more alive, whether the orchestra pit was playing the sun-filled, melodious rhythms of Tchaikovsky’s Spanish Dance in Swan Lake, the exhilarating Polish Krakowiak from Glinka’s opera Ivan Susanin, or the French Revolutionary melodies of The Flames of Paris. Her sudden arrest had clipped her wings on the eve of a new milestone in her career.

A sharp command from the guard brought an end to Nina’s first hours in prison. Pandemonium broke loose inside the cell as everybody jumped up and began to reorganise their quarters for the night. The prisoners pushed the tables to the side, and the wooden planks that had been piled in one of the corners were placed on top of boxes to create beds. Each inmate purposefully turned towards her assigned sleeping space, allocated strictly according to seniority by the starosta, the cell’s senior prisoner, who was in charge of maintaining order. Those who had been in prison longest got the best spots, newcomers the worst. Within five minutes the cell was transformed. Prisoners called up for nightly interrogations would have to stumble awkwardly towards the door along the narrow gaps between the beds. Women lay down on the tables and on top of the plank-beds to sleep, while new arrivals crawled underneath the planks. The starosta showed Nina her spot, probably somewhere on the floor. There was often only enough space to lie on one’s side. It was hard to breathe under the planks as the dust from the rotting wood above filled their nostrils.24

* At the time, the street was called Voinova Street.

* The All-Russian Extraordinary Commission for Struggle Against Counter-Revolution and Sabotage, known by its acronym Cheka, was the predecessor of the NKVD and KGB.

2

NINA

Nina’s arrest had put an abrupt end to a life centred on movement. She had always loved to dance and act. As a little girl she had often accompanied her mother to her performances. Home alone, she would put on her mother’s costumes, curiously observing her reflection as she danced in front of the mirror. Blissfully ignoring the fact that the garments were slipping off her shoulders and trailing on the floor, she would experiment with movements until the clothes became too creased to be used in her mother’s next performance.1 Not even the revolution had curbed her enthusiasm: Nina started her first dancing lessons in a private studio founded in 1917 by Baron Miklos in the former residence of Princess Ekaterina Yurievskaya, mistress and morganatic wife of Tsar Alexander II.2

Nina showed promise, but that alone was not always enough to secure a place at the Petrograd Choreographic Institute, formerly known as the Theatre School.* The revolution had opened the doors of Russia’s oldest ballet school to children of the upper-middle and even the upper classes, whose families would previously have categorically forbidden them to train as performers. The imperial ballet had recruited its students primarily from families already employed by the imperial theatres as artists, ushers, tailors and so forth. But the revolution was making life difficult for ‘former people’, the Bolsheviks’ derogatory term for Russia’s former elites, namely the nobility, officers of the Imperial Army, high-ranking bureaucrats, the merchant class and the clergy. Barred from institutions of higher education as class enemies, children from Russia’s most illustrious families were turning towards performing. In the chaos of post-revolutionary Petrograd, the Choreographic Institute distinguished itself as an oasis of pre-revolutionary culture, though it was not certain whether ballet as an art form would ultimately survive the Bolshevik Revolution. Ballet was identified with the old regime – the Romanov dynasty that had patronised it, and the ruling classes who had enjoyed it. The first commissar in charge of culture, Commissar* of Enlightenment Anatoly Lunacharsky, fought to keep alive the cultural institutions of imperial Russia, against the opposition of comrades who condemned Russian ballet as ‘a specific creation of the landowner’s regime, a caprice of the court’ intrinsically alien to Communism and the proletariat.3

Despite ballet’s uncertain future, winning a place at the school remained challenging. Applicants used whatever connections they had to gain points against competitors. Nina’s parents enlisted the help of her aunt, who was married to a well-known actor at the Alexandrinsky Theatre. Evdokia Osipovna took her lanky niece to a performance by an acquaintance, the ballerina Olga Preobrazhenskaya, and led her to Preobrazhenskaya’s changing room. Approaching fifty, Preobrazhenskaya was celebrated for her musicality and purity of form, but she was also a gifted teacher, and in charge of the senior girls at the school. The famous ballerina cast a glance at the girl with her expressive eyes, and passed her judgement: ‘Well, what a little old lady, what a skinny thing. But maybe something will become of her.’4 Before the beginning of the new academic year, the school’s strict entrance commission had selected Nina for admission.

In the autumn of 1919, Nina became a student at the Choreographic Institute.5 Each day, she travelled into town from the suburb Old Peterhof, returning after a long day filled with dance classes, rehearsals and regular academic classes.6 Times were uncertain. Revolutionary Russia was enveloped in civil war. The anti-Bolshevik White Russian forces were mounting a last challenge to the Red Army. But whenever Nina pushed open the heavy doors of the school, she entered a universe that seemed to exist outside time and space.

Noisy conversations, running along the corridors and similar infringements on etiquette were strictly forbidden. Whenever an adult approached, the girls would sink into a deep curtsey and the boys would bow, greeting the grown-up in French. A graduate of the illustrious Smolny Institute for Noble Girls, inspectress Varvara Ivanovna Likhosherstova had been tyrannising the girls of the Theatre School for almost forty years. Dressed in black in winter and grey in summer, the tall, silver-haired woman could have been called beautiful. But whenever she became angry, her translucent blue eyes would fade until they were almost white and her dark pupils would penetrate her victim like nails. However, the revolution had softened even this tyrant. Varvara Ivanovna began to look warmly at her hungry charges, who were devoting themselves to St Petersburg’s classical ballet tradition under almost impossible conditions.7

Ballet had occupied a special place in imperial St Petersburg. The tsars had brought ballet to Russia from France and Italy, but from the mid-eighteenth century it had grown deep roots in Russian soil and acquired its own distinct flavour by absorbing influences from Russia’s rich folk-dance tradition. By the nineteenth century, St Petersburg had become the international capital of ballet. Under the guidance of the French ballet master and choreographer Marius Petipa, the Russian imperial ballet created the masterworks that still define our understanding of classical ballet: Swan Lake, The Sleeping Beauty, Don Quixote, La Bayadère and The Nutcracker. In imperial St Petersburg, ballet was associated with the city’s high society, who went to the Mariinsky Theatre to see and to be seen. The term balletoman was coined to describe the fanatical admirers of the ballet, whose worship of ballerinas could take absurd extremes: it is said that a group of St Petersburg balletomans bought a pair of pointe shoes worn by the romantic ballerina Marie Taglioni and cooked and ate them for supper.

The school was now trying to pass on its imperial ballet tradition to the next generation of dancers against a revolutionary ideology that saw ballet as class-alien. Conditions were tough. During her academic lessons, Nina would look quizzically at the ink that had frozen in the bitterly cold classrooms of the unheated school, shuddering in her winter coat while trying to wriggle her numb toes in their felt boots. Always hungry* and cold, Nina and her classmates would enter one of the studios, their bodies adjusting to the sloped wooden floor built to prepare them for the raked stage of the former Mariinsky Theatre,† and wait for their teacher, the former soloist Zinaida Vasilyevna Frolova. A diminutive woman of advanced years, Frolova entered the studio wrapped in a cloak, a fur cap playfully pinned to a rust-coloured wig framing a pretty face with fine features. Her legs always maintained a perfectly turned-out first position, even while walking in impossibly high heels. Frolova had high hopes for Nina’s future, envisioning her as a ballerina at the Mariinsky Theatre. Sometimes she asked Nina to show her fourth arabesque to the whole class, waxing lyrical about the suppleness of her spine and her classical line.8

In 1921, after shuttling between her family’s home in Old Peterhof and the school in the centre of Petrograd for more than a year, Anisimova’s father successfully petitioned that Nina be admitted to the school’s boarding school. Like apparitions from a time long gone, the forty boarders would walk in their prunella boots along the school’s dark corridors, their long, cornflower-blue dresses gently swishing over the floor. Their shoulders were covered with white pelerines, their ends tucked into long black aprons, white ones on special occasions.9 The girls slept in one dormitory, strictly separated from the boys who were quartered on a higher floor.10

Passers-by watched with curiosity whenever the girls filed out in pairs into Theatre Street* for their daily walk, promenading in institutional coats with puff sleeves, muffs hanging from their necks. On evenings when the children were participating in performances at the former Mariinsky Theatre, a wide, horse-drawn wagon would pull up in front of the school at around half past six in the evening. Street boys would run after the vehicle, merrily shouting at the girls in their long coats and blue felt hats: ‘Ballet rats, ballet rats! Going to dance!’ In winter the students were driven to the theatre in a low, wide sledge. Squashed up together, they would tumble into the snow whenever the sledge turned over, giggling hysterically and ignoring the angry looks of the ladies chaperoning them, to the delight of the street boys who would exclaim: ‘The ballet rats have been thrown on the dump!’11

Nina was progressing at the school, but her body was changing. In her first years, her teacher had high hopes for her talented pupil. Now, all of a sudden, she had become a ‘difficult case’. Towering over her classmates after a growth spurt, her body no longer seemed to belong to her. Gone were some of the physical abilities that she had taken for granted. By the time she came under the wing of Agrippina Vaganova, the school’s foremost classical teacher in the girls’ division, there was nothing exceptional about her physical gifts. On the contrary, her figure now had some peculiarities that made it more difficult for her to achieve a beautiful line in her movements. In class, feeling awkward about her height, her long legs and her angular body, Nina tried to make herself invisible by standing at the back of the studio, seeking cover behind the backs of her classmates. But nobody could hide from Vaganova’s eyes, and especially nobody who intrigued her.

Nina had feared that Vaganova would take absolutely no interest in her because she could never be turned into a first-rate classical ballerina. She was wrong. Halfway through each class, Vaganova would without fail plant herself right in front of Nina and ask: ‘Well, well, so show me what you are doing here?’ She had noticed Nina’s rare expressiveness and was already sensing that, with the right guidance, this slightly awkward girl could be transformed into something extraordinary. Nina would become Vaganova’s favourite character dancer, but for now she was being pushed to adapt her body to the aesthetics of classical dance. Mastering the combinations in Vaganova’s class would give Nina the key to expressing the full range of human emotions in dance: each step had to be executed not just technically perfectly, but with maximum expressivity. In Vaganova’s class, Nina learned to infuse dance with the essence of her whole being and to give meaning to every movement.12

Vaganova did not confine herself to initiating Nina into the secrets of classical dance. Sometimes she would keep Nina back after class and go over character-dance movements with her. But Vaganova was not the only one who had taken Nina under her wing.

In the early 1900s, Alexander Shiryaev had created the first character-dance class for the school. At the time, there was no specialised training. Often, character dance was left to those who were technically too weak to perform classical parts. The character dances themselves also left much to be desired in terms of virtuosity and versatility. Dissatisfied, Shiryaev convinced another senior character dancer of the theatre, the Hungarian Alfred Bekefi, to go back to the sources. For two years, Bekefi and Shiryaev studied folk dances as they were performed by different national groups. Back in Petersburg, Shiryaev analysed the material he had collected and, mirroring a traditional ballet class, invented specific exercises at the barre and in the centre of the studio to prepare dancers for the more virtuoso demands of character dance. With Petipa’s support, Shiryaev received permission to teach his character-dance class at the school in 1905, but the classes stopped when Shiryaev quit his teaching position three years later.13 When Shiryaev came back to the school in 1918, the character-dance classes returned with him.

For the rest of her life, Nina would remember the day Shiryaev walked into one of Vaganova’s classes and singled her out. From then on, Nina worked towards her new goal: to become the best character dancer she could be.

Short of stature, Shiryaev had a large head with a beaked nose, a deep, rumbling voice and almost ridiculously small feet which, in their flat, feminine slippers, transfixed Nina in class. Demonstrating increasingly difficult technical feats, Shiryaev’s feet would acquire a life of their own, moving even at the highest velocity with such delicate agility that they ‘seemed to be able to speak’.14

He began carefully to initiate Nina into the Mariinsky’s classical character-dance repertoire: the pas de mantille from Paquita, the czardas and mazurka from Coppélia, the Indian dance from La Bayadère. But Shiryaev also composed new pieces, showcasing his charges’ particular talents. His ability to predict a student’s future artistic personality could be uncanny. For Nina he staged a Spanish duet, correctly sensing the important role that Spanish dances would play in Nina’s future career.

A year before Nina’s graduation, Vaganova prepared her for performing a classical variation from Arthur Saint-Léon’s ballet La Source at the school’s annual graduation presentation at the former Mariinsky Theatre. This was the first and last time that Nina danced in a serious classical piece, and years later she remembered how out of place she had felt dancing it.15 But people outside the walls of the school were beginning to take notice of her as a character dancer. By the time she was in her last year, her character-dancing had become technically precise and stylistically exquisite. But it was her strong artistic personality that stood out. Critics praised her fire, passion and temperament and noted that there was nothing affected in her style. At her graduation performance Nina had a leading role, Nirilya in Petipa’s ballet Talisman. The critic Yuri Brodersen wrote: ‘The young artist dances with great élan and temperament. The fire of an enticing gaiety animates her face. Her gestures are broad and bold, powerfully and impetuously seizing the air.’

But there was an important dimension to Nina’s dancing, even in this old-fashioned ballet about a young goddess and a maharaja in ancient India: Nina had matured into a distinct artistic personality who seemed instinctively in touch with the pulse of her own times. Earlier that year, another critic had written about Nina’s performance in another Petipa ballet, The Cavalry Halt: ‘Anisimova, who is graduating this year, convinced us once more that our academic stage is gaining in her an artist who is full of fire, temperament, precisely expressive, without affection, who is feeling the present. There is no doubt that in the new type of ballet, which without doubt will take root in our choreographic repertoire in the immediate future, there will be an especially urgent need precisely for character dancers like this.’16

Luckily for Nina, character dance was on the ascent, both artistically and ideologically. Ballet’s detractors were continuing to attack classical dance as degenerate entertainment for the rich. The Bolshevik class-war rhetoric gave character dance the opportunity to step out of the shadow of classical dance: ballet was supposed to become more ‘democratic’, and character dance was by definition more democratic than classical dance because it was rooted in folk dance. By giving greater prominence to character dance, the ballet companies could demonstrate their willingness to ‘democratise’.

Everybody seemed to expect that Nina would graduate smoothly into the company of the former Mariinsky. But the company’s management could find no vacancy for her. Instead, Nina had to start her career at Leningrad’s second opera house, the Maly Theatre.* At the time, the repertoire for dancers at the Maly was very limited as the theatre did not yet have its own independent ballet company. Instead, its ballet ensemble serviced the theatre’s opera and operetta performances. She started performing the czardas in operettas, urban dances like the foxtrot and other jazzy numbers. But the Maly had something else to offer: under its director, the conductor Samuil Samosud, it had become the laboratory for new Soviet opera. After her traditional training, Nina found herself at a centre for artistic experimentation.

Nina would walk restlessly around Leningrad, trying to make sense of everything she was experiencing. Watching the innovative work around her, she realised that her work at the Maly was not enough. She wanted to find her own artistic voice. Like many in her generation, she was looking for truth in art beyond the established forms she had been taught. But for this she needed to experiment. The jumble of thoughts and ideas in her head could be overwhelming, but the strict, harmonious classicism of her native city came to her rescue, calming her over-stimulated imagination. A few years later, Nina would write: ‘In these years, I sensed and for the first time consciously grasped the lyrical and severe beauty of our unusual city. Taking in the choppy waters of the cold-grey Neva contained by the granite river-bed, much of the confusion in my thoughts about art came into focus and found its form, much was resolved as I grasped the architectural clarity in the profile of its squares.’17

Seeking an outlet for her restless creative energies, Nina began to explore Leningrad’s thriving variety stages.18 Many ballet artists were looking for extra work, even though some theatres forbade them to do so. One reason was financial – the basic salary of a corps de ballet dancer was enough to provide food for only half a month – but many also enjoyed the freedom to experiment. Ballet dancers performed before movie showings at cinemas, at concert halls, outdoor performance spaces, small theatres and even at gambling clubs and private restaurants.19

Nina danced in mixed programmes put together for workers, in cinema-divertissements, at Leningrad’s popular Summer Garden and on the stage of the Philharmonic. Sometimes she performed character dances from the classic repertoire, but she also began to choreograph her own pieces and started to work with another young dancer and budding choreographer, Vasily Vainonen. It was probably around this time that Nina first met Vladimir ‘Volodia’ Dmitriev, an artist who had become a rising star among stage designers. Volodia was Vainonen’s mentor, and he had also designed productions for the Maly. Both men would play a decisive role in Nina’s career and life.

But Nina still felt unsatisfied – her own efforts were not enough to break the tedium of the Maly’s repertoire. Fate came to her help. During a performance of Ernst Krenek’s comic avant-garde opera Der Sprung über den Schatten around New Year 1927–8, a 600-kg disc suspended over the stage accidentally collapsed and almost killed Nina, who was carried off stage and hurried to hospital. Nina was convinced that the theatre management took pity on her because of this accident, transferring her to the former Mariinsky after her recovery. She had spent barely one season at the Maly.20

Nina arrived during tumultuous times. Towards the end of her first season, in May 1928, Soviet citizens were listening with bated breath to reports about the Shakhty trial of non-Bolshevik engineers and technicians on charges of conspiracy and sabotage. The regime was renewing its battle against non-Communist, bourgeois specialists. After the comparative calm and pragmatism of the New Economic Policy (NEP), class war was back, and not just in the economy and in industry. Communist militants were fighting against the old intelligentsia for absolute control of the arts, education and the sciences. Government authority over the theatres’ repertoire was tightened, and the former Mariinsky’s modernist ballet director Fedor Lopukhov came under attack and was removed from his position. Pressure to Sovietise the ballet repertoire increased.

Nina threw herself into the traditional character dances of the classical repertoire: the Ukrainian dance from The Little Hump-backed Horse, the Spanish Dance from Swan Lake, the Saracen dance from Raymonda. She still had a lot to learn, but she was already attracting attention. When the company’s most senior male character dancer, Joseph Kschessinsky, chose her as his partner for the jubilee performance marking his sixtieth birthday, Nina modestly claimed that he had honoured her as the youngest character dancer in the company. But their czardas was equal to a coronation dance: Kschessinsky not only had great authority within the company, he was a member of an important ballet dynasty and the brother of the fabled ballerina Mathilda Kschessinskaya, mistress of the young Nicholas II, who was now living in French exile with her husband, Grand Duke Andrei Vladimirovich Romanov.21

Nina was still trying to define her artistic personality. She felt that, deep inside, a part of her creativity was still waiting to be awakened. Her unique gift finally revealed itself to her – and to the world – during the rehearsals for The Flames of Paris.* The part of Thérèse had not even been in the ballet’s original libretto, but Nina kept adding layer upon layer of meaning during the rehearsals for the revolutionary mass scenes and the small Basque group dance she was supposed to perform until the character of Thérèse was born. It might have helped that the ballet’s core creative team was an experimental one, open to improvisation: the choreographer was Vasily Vainonen, guided by the theatre director, Sergei Radlov, and stage designer Volodia Dmitriev.22

Directors from the dramatic theatre were supposed to help ballet and opera find a new, Soviet seriousness. Six months before the premiere of The Flames of Paris on 7 November 1932, the anniversary of the revolution, ‘socialist realism’ had been declared the mandatory method of artistic creation in all branches of the arts, but nobody knew what this was supposed to mean in practice; each art form embarked on the arduous process of interpreting it for itself. In the world of ballet, Radlov became the midwife to a new genre that would define Soviet ballet for decades to come: drambalet, narrative ballets constructed according to the laws of the dramatic theatre, often on the basis of classic literature or contemporary plots reminiscent of Soviet propaganda movies.*

The critics had sensed correctly that Nina’s creative core was deeply contemporary. She found herself as an artist when she got the chance to characterise a real person: Nina discovered that she could express the savage fervour of Thérèse’s revolutionary heroism in dance. The ‘old’ character dances had added national flavour to ballets, or expressed a mood or temperament associated with a specific country. The Flames of Paris had shown Nina that character dance could also be dramatic. It could express the full range of human emotions and serve as a vehicle to build a character on stage.23 With this new freedom, Nina’s desire to choreograph larger pieces was awakened. Choreography was traditionally the domain of men, but, very subtly, Vaganova had set a precedent for female choreographers at the Kirov by adding her own choreography to her productions of the classics. Nina was ready to follow.

Nina staged her first larger independent work in 1935, a suite of Spanish dances performed by herself, two male dancers and a singer. The following two years proved exceptionally difficult for Russia’s classical ballet, but intensively stimulating for Nina. In the rollercoaster of Soviet cultural politics, she became the accidental beneficiary of an intensified clash between the creative intelligentsia’s artistic aspirations and the regime’s ideological demands.

To prove its right to exist in a Communist state, ballet had been exhorted year after year to contribute to the ideological education of the new Soviet man, but expressing Bolshevik propaganda in the courtly, elegant language of classical dance was easier said than done. The choreographer Fedor Lopukhov, the young star composer Dmitry Shostakovich and the librettist Adrian Piotrovsky seemed to have found a winning formula when their comedy ballet The Bright Stream, about life on a provincial Soviet collective farm, opened to great critical and public acclaim at the Maly Theatre in April 1935. Lopukhov’s innovative yet classical choreography and Shostakovich’s radiant music told a light-hearted story of love and jealousy between the inhabitants of the farm and a group of Muscovite ballet artists visiting to celebrate the farm’s impressive production quotas.

Disaster struck shortly after the ballet’s successful Moscow premiere at the Bolshoi in November 1935. A vicious series of unsigned Pravda editorials attacked different works of Soviet opera, ballet, film and the visual arts, marking the beginning of the notorious anti-formalism campaign against modernism that would paralyse Soviet artists. Artists were exhorted to resist the temptations of ‘capitalist’ Western art and to focus their energies on creating wholesome socialist realist art. Soviet art was supposed to be simple, inspired by folk art, life-affirming and optimistic, propagating an official version of Soviet existence that bore little resemblance to reality. Lopukhov was chastised for combining classical dance with false folk dances that had nothing to do with the folk art of Kuban, the Black Sea region settled by Cossacks where the ballet was set.24 Instead of crafting credible, contemporary Soviet characters for the stage, the ballet’s creators were accused of perpetuating pre-revolutionary conventions.

The Pravda attack pushed Leningrad’s ballet world into desperate attempts to stomp out frivolity. Nina found herself in charge of staging a one-act ballet for the Leningrad Choreographic Institute’s annual graduation performance at the Kirov in June 1936. Set in Spain, Andalusian Wedding was based on a work by the romantic Spanish writer Prosper Mérimée, author of Carmen, and told the story of a popular hero who, pursued by police, interrupts a wedding and is saved by the people.25 Nina was supported by one of Leningrad’s leading directors, Vladimir Solovyov.

After Andalusian Wedding, Nina was recognised as a new talent in choreography. Her star was ascending within the strict dance hierarchy of the former Mariinsky, renamed the Kirov Theatre in 1935 in honour of Leningrad’s assassinated party boss Sergei Kirov. The official promotion of national dance literally propelled her centre stage. Back in 1933, inspired by her rousing portrayal of Thérèse in his ballet The Flames of Paris, Vasily Vainonen had staged a special concert number for Nina that showed her as a female partisan leader of a small detachment uniting people of different nationalities. After a successful premiere, Vainonen and Dmitriev decided to use it as the starting point for a new ballet libretto about the civil war: Partisan Days.26

In March 1936, just a few weeks after the attack on The Bright Stream, the Kirov took the plunge and agreed to stage Partisan Days. It was to be the Kirov’s first – and last – contemporary ballet based entirely on character dance. The moment seemed to belong to Nina and her partner, Sergei Koren. Dissatisfied by the Kirov’s limited repertoire for character dancers, they had just started experimenting together beyond the walls of the theatre.27 Now they could do so at the Kirov itself, the heart of Russian ballet culture. Nina and Koren were to be the stars of Partisan Days; Vainonen stubbornly resisted the pressure to include a role for a classical ballerina. Not a single pointe shoe could be spotted during the premiere on 10 May 1937. Nina was the ballet’s central heroine, portraying a rebellious young Cossack woman who joins a group of partisans during the civil war that had followed the October Revolution. The theatre’s classical ballerinas watched from the wings in disbelief, shuddering at the thought that they might be forced to hang up their own pointe shoes for good.

By an accident of fate, Nina had come to embody the Soviet aspiration of bringing culture to the masses and of forging a unique Soviet civilisation through art. She not only excelled in the fiery national dances that added spice and local colour to ballets, but her choreographic interpretations of dances from different Soviet regions were an ideal vehicle for demonstrating the ‘brotherhood’ that supposedly united the many nationalities that had been brought into the Soviet fold since the early days of the revolution, when Stalin had been Commissar of Nationalities. Despite formidable opposition from the traditional ballerinas, who were not willing to relinquish their monopoly on leading roles without a fight, and the usual theatrical backstabbing, Nina had held her course. But her arrest put an end to her ascent.

* Russia’s oldest ballet school underwent several name changes. At the time of its foundation in 1738 it was simply referred to as Dance School. Today, it is called the Vaganova Academy of Russian Ballet. For the period discussed in this chapter, I will sometimes refer to the school as Theatre School and sometimes as Choreographic Institute, reflecting the custom of the time.

* Soviet commissars served a function akin to ministers.

* During these hungry years, the legendary ballerina Anna Pavlova sent the students of her alma mater packages with cornflour porridge and cocoa from abroad.

† In 1920, the Mariinsky was renamed the State Academic Theatre of Opera and Ballet, GATOB. In 1935, it was renamed the Kirov Theatre of Opera and Ballet. Colloquially, after the revolution, it was often referred to as the former Mariinsky. For simplicity’s sake I will refer to the theatre as the former Mariinsky for the years 1917–35, and as the Kirov for the period thereafter.

* The street was renamed Rossi Street in 1923.

* Dmitry Shostakovich’s operas The Nose (1930) and Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk (1934) both had their premiere at the Maly. Today, the theatre is known as the Mikhailovsky Theatre.

* The ballet’s premiere took place at the former Mariinsky on 7 November 1932 in honour of the fifteenth anniversary of the revolution.

* Later, the genre would ossify into pantomimic performances of little choreographic interest, but during its early days, the collaboration between innovative theatre directors and the former Mariinsky Ballet was truly innovative. Its crowning achievement would be Leonid Lavrovsky’s staging of Sergei Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet, who had worked on the ballet’s libretto with Radlov and Adrian Piotrovsky.

3

ENEMY OF THE PEOPLE

The black curtain covering the cell’s steel-rod wall was pushed to the side:

‘Somebody with the letter “A”?’

‘Anisimova?’

‘Full initials!’

‘Nina Alexandrovna.’

‘To the exit!’

It was Nina’s third night in prison. Interrogations only took place at night, to catch the prisoners in their psychologically most vulnerable state. Whenever the guard approached the cell to collect a prisoner for interrogation, the inmates had to participate in a nerve-wracking charade. The guard would only give the first letter of the surname he was looking for. Woken from their troubled sleep, all prisoners whose last name started with the letter in question had to give their full name until the right prisoner was found. If the guard had approached the wrong cell, the identity of the prisoner he was looking for would remain secret. This was supposed to